Unemployment in the United States

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Economy of the United States |

|---|

|

Unemployment in the United States discusses the causes and measures of U.S. unemployment and strategies for reducing it. Job creation and unemployment are affected by factors such as economic conditions, global competition, education, automation, and demographics. These factors can affect the number of workers, the duration of unemployment, and wage levels.

Overview[edit]

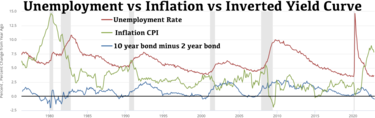

Unemployment generally falls during periods of economic prosperity and rises during recessions, creating significant pressure on public finances as tax revenue falls and social safety net costs increase. Government spending and taxation decisions (fiscal policy) and U.S. Federal Reserve interest rate adjustments (monetary policy) are important tools for managing the unemployment rate. There may be an economic trade-off between unemployment and inflation, as policies designed to reduce unemployment can create inflationary pressure, and vice versa. The U.S. Federal Reserve (the Fed) has a dual mandate to achieve full employment while maintaining a low rate of inflation. The major political parties debate appropriate solutions for improving the job creation rate, with liberals arguing for more government spending and conservatives arguing for lower taxes and less regulation. Polls indicate that Americans believe job creation is the most important government priority, with not sending jobs overseas the primary solution.[3]

Unemployment can be measured in several ways. A person is defined as unemployed in the United States if they are jobless, but have looked for work in the last four weeks and are available for work. People who are neither employed nor defined as unemployed are not included in the labor force calculation. For example, as of September 2017, the unemployment rate (formally defined as the "U-3" rate) in the United States was 4.2% representing 6.8 million unemployed people.[4][5] The unemployment rate was calculated by dividing the number of unemployed by the number in the civilian labor force (age 16+, non-military and not incarcerated) of approximately 159.6 million people,[6] relative to a U.S. population of approximately 326 million people.[7] The historical average unemployment rate (January 1948-September 2020) is 5.8%.[4] The government's broader U-6 unemployment rate, which includes the part-time underemployed was 8.3% in September 2017.[8][9] Both of these rates fell steadily from 2010 to 2019; the U-3 rate was below the November 2007 level that preceded the Great Recession by November 2016, while the U-6 rate did not fully recover until August 2017.[4][8]

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) publishes a monthly "Employment Situation Summary" with key statistics and commentary.[10] As of June 2018, approximately 128.6 million people in the United States have found full-time work (at least 35 hours a week in total), while 27.0 million worked part-time.[11] There were 4.7 million working part-time for economic reasons, meaning they wanted but could not find full-time work, the lowest level since January 2008.[12]

The vast majority of persons outside the civilian labor force (age 16+) are there by choice. The BLS reported that in July 2018, there were 94.1 million persons age 16+ outside the labor force. Of these, 88.6 million (94%) did not want a job while 5.5 million (6%) wanted a job.[13] Key reasons persons age 16+ are outside the labor force include retired, disabled or illness, attending school, and caregiving.[14] The Congressional Budget Office reported that as of December 2017, the primary reason for men age 25–54 to be outside the labor force was illness/disability (50% or 3.5 million), while the primary reason for women was due to family care-giving (60% or 9.6 million).[15]

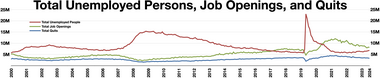

The Congressional Budget Office estimated that the U.S. was approximately 2.5 million workers below full employment as of the end of 2015 and 1.6 million at December 31, 2016, mainly due to lower labor force participation. This was very close to full employment, indicating a strong economy.[16] As of May 2018, there were more job openings (6.6 million) than people defined as unemployed (6.0 million) in the U.S.[17][18][19]

In September 2019, the U.S. unemployment rate dropped to 3.5%, near the lowest rate in 50 years.[20] On May 8, 2020, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that 20.5 million nonfarm jobs were lost and the unemployment rate rose to 14.7 percent in April, due to the Coronavirus pandemic in the United States.[21]

Definitions of unemployment[edit]

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics has defined the basic employment concepts as follows:[23]

- People with jobs are employed.

- People who are jobless, looking for jobs within the last 4 weeks, and available for work are unemployed.

- People who are neither employed nor have looked for a job within the last 4 weeks are not included in the labor force.

Employed[edit]

Employed persons consist of:

- All people who did at least one hour of work for pay or profit during the survey reference week.

- All people who did at least 15 hours of unpaid work in a family-owned enterprise operated by someone in their household.

- All people who were temporarily away, whether they were on vacation, sick, or laid off[24] from their regular jobs, including paid or unpaid absences.

Full-time employed persons work 35 hours or more, considering all jobs, while part-time employed persons work less than 35 hours.

Unemployed[edit]

Who is counted as unemployed?

- People are classified as unemployed if they do not have a job, have actively looked for work in the prior 4 weeks, and are currently available for work.

- Workers expecting to be recalled from layoff are sometimes counted as unemployed, depending on the specific interviewer.[24] They are expected to be counted whether or not they have engaged in a specific job-seeking activity.

- In all other cases, the individual must have been engaged in at least one active job search activity in the 4 weeks preceding the interview and be available for work (except for temporary illness) in order to be counted as unemployed.

The number of people collecting unemployment benefits is much lower than the actual number of unemployed people, since some people are not eligible, or do not apply.[25]

Labor force[edit]

Who is not in the labor force?

- Persons not in the labor force are those who are not classified as employed or unemployed during the survey reference week.

- Labor force measures are based on the civilian noninstitutional population 16 years old and over. (Excluded are persons under 16 years of age, all persons confined to institutions such as nursing homes and prisons, and persons on active duty in the Armed Forces.)

- The labor force is made up of the employed and those defined as unemployed. Expressed as a formula, the labor force equals employed plus unemployed persons.

- The remainder (those who have no job and have not looked for one in the last 4 weeks) are counted as "not in the labor force." Many who are not in the labor force are going to school or are retired. Family responsibilities keep some others out of the labor force.

- "Marginally attached" workers are those not in the labor force because they have not searched for a job in the prior 4 weeks. However, they have searched in the prior 12 months and are both available for work and want to do so. Most marginally attached workers are not searching due to being discouraged over job prospects or due to being in school.

U.S. employment history[edit]

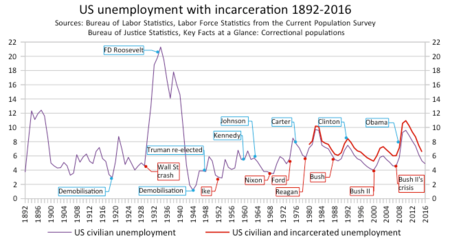

During the 1940s, the U.S. Department of Labor, specifically the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), began collecting employment information via monthly household surveys. Other data series are available back to 1912. The unemployment rate has varied from as low as 1% during World War I to as high as 25% during the Great Depression. More recently, it reached notable peaks of 10.8% in November 1982 and 14.7% in April 2020. Unemployment tends to rise during recessions and fall during expansions. From 1948 to 2015, unemployment averaged about 5.8%. There is always some unemployment, with persons changing jobs and new entrants to the labor force searching for jobs. This is referred to as frictional unemployment. For this reason, the Federal Reserve targets the natural rate of unemployment or NAIRU, which was around 5% in 2015. A rate of unemployment below this level would be consistent with rising inflation in theory, as a shortage of workers would bid wages (and thus prices) upward.[26]

Jobs created by Presidential term[edit]

Job creation is reported monthly and receives significant media attention, as a proxy for the overall health of the economy. Comparing job creation by President involves determining which starting and ending month to use, as recent Presidents typically begin in January, the fourth month into the last fiscal year budgeted by their predecessor. Journalist Glenn Kessler of The Washington Post explained in 2020 that economists debate which month to use as the base for counting job creation, between either January of the first term (the month of inauguration) or February. The Washington Post uses the February jobs level as the starting point. For example, for President Obama, the computation takes the 145.815 million jobs of February 2017 and subtracts the 133.312 million jobs of February 2009 to arrive at a 12.503 million job creation figure. Using this method, the five Presidents with the most job gains (in millions) were: Bill Clinton 22.745; Ronald Reagan 16.322; Barack Obama 12.503; Lyndon B. Johnson 12.338; and Jimmy Carter 10.117. Four of the top five were Democrats.[28]

The Calculated Risk blog also reported the number of private sector jobs created by Presidential term. Over 10 million jobs were created in each of President Clinton's two terms during the 1990s, by far the largest number among recent Presidents. President Reagan averaged over 7 million in each term during the 1980s, while George W. Bush had negative job creation in the 2000s. Each of these Presidents added net public sector (i.e., government) jobs, except President Obama.[29][30][31]

Writing in The New York Times, Steven Rattner compared job creation in the last 35 months under President Obama (2014-2016) with the first 35 months of President Trump (2017-2019, i.e., pre-coronavirus). President Obama added 227,000 jobs/month on average versus 191,000 jobs/month for Trump, nearly 20% more. The unemployment rate fell by 2 percentage points under Obama versus 1.2 points under Trump.[32]

[edit]

In March 2020, during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, American unemployment saw a huge increase; claims in one week rose to 3.3 million from 281,000 on the previous week. The previous record for unemployment claims in one week was only about one fifth as high, at 695,000 claims in 1982.[33]

More than 38 million Americans lost their jobs and applied for government aid,[34][35] including nearly 4 million people in California,[36] in the eight weeks since the coronavirus pandemic began.

Recent employment trends[edit]

There are a variety of measures used to track the state of the U.S. labor market. Each provides insight into the factors affecting employment. The Bureau of Labor Statistics provides a "chartbook" displaying the major employment-related variables in the economy.[37][38] Members of the Federal Reserve also give speeches and Congressional testimony that explain their views of the economy, including the labor market.[39]

As of September 2017, the employment recovery relative to the November 2007 (pre-recession) level was generally complete. Variables such as the unemployment rates (U-3 and U-6) and number of employed have improved beyond their pre-recession levels. However, measures of labor force participation (even among the prime working age group), and the share of long-term unemployed were worse than pre-crisis levels. Further, the mix of jobs has shifted, with a larger share of part-time workers than pre-crisis. For example:

Unemployment rates[edit]

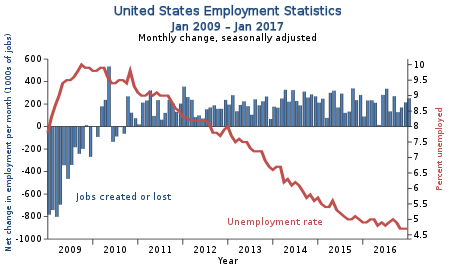

- The unemployment rate (U-3), measured as the number of persons unemployed divided by the civilian labor force, rose from 5.0% in December 2007 to peak at 10.0% in October 2009, before steadily falling to 4.7% by December 2016 and then to 3.5% by December 2019.[40] By August 2023, it reached 3.8 percent.[41]

This measure excludes those who have not looked for work in the last 4 weeks and all other persons not considered as part of the labor force, which can distort its interpretation if a large number of working-aged persons become discouraged and stop looking for work.

- The unemployment rate (U-6) is a wider measure of unemployment, which treats additional workers as unemployed (e.g., those employed part-time for economic reasons and certain "marginally attached" workers outside the labor force, who have looked for a job within the last year, but not within the last 4 weeks). The U-6 rate rose from 8.8% in December 2007 to a peak of 17.1% in November 2009, before steadily falling to 9.2% in December 2016 and 7.6% in December 2018.[42]

- The share of unemployed who have been out of work for 27 or more weeks (i.e., long-term unemployed) averaged approximately 19% pre-crisis; this peaked at 48.1% in April 2010 and fell to 24.7% by December 2016 and 20.2% by December 2018.[43] Some research indicates the long-term unemployed may be stigmatized as having out-of-date skills, facing an uphill battle to return to the workforce.[44]

Level of employment and job creation[edit]

- Civilian employment, one measure of the size of the employed workforce, expanded consistently during the 1990s, but was inconsistent during the 2000s due to recessions in 2001 and 2008–2009. From 2010 onward, it steadily rose through October 2017.[45] For example, employment did not recover its January 2001 peak of 137.8 million until June 2003. Then, from the bubble-assisted peak in November 2007 of 146.6 million, 8.6 million jobs were lost due to the global economic crisis, with employment falling to 138.0 million. U.S. employment began rising thereafter and regained the pre-crisis peak by September 2014. By December 2016, civilian employment was 152.1 million, 5.5 million above the pre-crisis level and 14.1 million above the trough. By October 2017, 153.9 million were employed.[46]

- From October 2010 to November 2015, the U.S. added a total of 12.4 million jobs, with positive job growth each month averaging 203,000, a robust rate by historical standards.[46][47] Analysis of labor force trends for 2015 indicated that it was mainly persons that did not want jobs, rather than discouraged or marginally attached workers, which was slowing the rate of growth of the labor force.[48]

- Job creation in 2014 was the best since 1999. As of October, the economy had added 2.225 million private sector jobs, and 2.285 million total jobs.[49] In contrast, in 2018 the economy gained over 2.6 million total jobs including 312,000 in December alone. Such an accomplishment was largely due to consumer confidence, President Trump's stringent deregulation in the private sector and large tax cuts.[50]

- Government employment (federal, state and local) was 22.0 million in November 2015, similar to August 2006 levels. This contrasts with steady increases in government employment 1980–2008.[51] Federal government employment was 2.7 million in November 2015, also similar to pre-recession (2007) levels. It had risen roughly 200,000 workers in the aftermath of the crisis then fell back again.[52]

- Labor market growth has fluctuated in 2023, slowing to 165,000 jobs in March and rebounding to 253,000 jobs in April. The number of jobs added is still down from this time in 2022 when 390,000 jobs were added to the economy.[53]

Labor force participation[edit]

- The labor force participation rate (LFPR) is defined as the number of persons in the labor force (i.e., employed and unemployed) divided by the civilian population (aged 16+). This ratio has steadily fallen from 67.3% in March 2000 to 62.5% by May 2016.[54] The decline is long-term in nature and is primarily driven by an aging country, as the Baby Boomers move into retirement (i.e., they are no longer in the labor force but are in the civilian population). Other factors include a higher proportion of working aged persons on disability or in school.[55]

- Another measure of workforce participation is the civilian employment-to-population ratio (EM Ratio), which fell from its 2007 pre-crisis peak of approximately 63% to 58% by November 2010 and partially recovered to 60% by May 2016. This is computed as the number of persons employed divided by the civilian population.[56] This measure is also affected by demographics.

- Analysts can adjust for the effect of demographics by examining the ratio for those "prime-working aged" persons aged 25–54. For this group, LFPR fell from 83.3% in November 2007 to a trough of 80.5% in July 2015, before partially recovering to 81.8% in October 2017. The EM ratio for this group fell from its November 2007 level of 79.7% to a trough of 74.8% in December 2009, before recovering steadily towards 78.8% in October 2017. In both cases, the ratios had yet to reach their pre-crisis peaks, a possible indicator of "slack" in the labor market with some working-age persons on the sidelines.[57][58]

- The Congressional Budget Office estimated that the U.S. was approximately 2.5 million workers below full employment as of the end of 2015 and 1.6 million at December 31, 2016, mainly due to lower labor force participation.[16]

- In December 2015, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) reported the reasons why persons aged 16+ were outside the labor force, using the 2014 figure of 87.4 million: 1) Retired-38.5 million or 44%; 2) Disabled or Illness-16.3 million or 19%; 3) Attending school-16.0 million or 18%; 4) Home responsibilities-13.5 million or 15%; and 4) Other Reasons-3.1 million or 5%.[14] As of February 2018, BLS characterizes an estimated 90 million of the 95 million people outside of the labor force as people who "do not want a job now" and stipulates that this number "includes some persons who are not asked if they want a job." BLS defines those who "do not want a job now" as people who have not looked for work within the last 4 weeks.[59]

- Economist Alan Krueger estimated in 2017 that "the increase in opioid prescriptions from 1999 to 2015 could account for about 20 percent of the observed decline in men's labor force participation during that same period, and 25 percent of the observed decline in women's labor force participation." An estimated 2 million men in the age 25-54 age range who are outside the labor force took prescription pain medication daily during 2016.[60]

Mix of full-time and part-time jobs[edit]

- The number of part-time workers jumped during 2008 and 2009 as a result of the recession, while the number of full-time workers fell. This pattern is consistent with previous recessions. From November 2007 to January 2010, the number of part-time workers increased by 3.0 million (from 24.8 million to 27.8 million), while the number of full-time workers fell by 11.3 million (from 121.9 million to 110.6 million). Between 2010 and May 2016, the number of part-time workers fluctuated between approximately 27–28 million, while the number of full-time workers recovered steadily to 123.1 million, above the pre-crisis peak.[61] In other words, nearly all of the post-recession job creation was full-time.

- The share of full-time jobs was 83% in 2007, but fell to 80% by February 2010, recovering steadily to 81.5% by May 2016.[62]

- The number of persons working part-time for economic reasons remained above the pre-crisis level as of August 2016. The number rose from 4.6 million in December 2007 (pre-crisis) to a peak of 9.7 million in March 2010, before falling to 6.0 million in August 2016. Measured as a percent of total employed in the private sector, the figures were 3.3%, 7.1%, and 4.0%, respectively.[63] Federal Reserve Governor Lael Brainard cited this as an indicator of labor market slack in a September 2016 speech.[64]

- Measured between 2005 and 2015, the net job creation was in alternative work arrangements (i.e., contract, temporary help, on-call, independent contractors or freelancers). Some of these workers may qualify as full-time (greater than 35 hours/week) while others are part-time. In other words, the number of workers in traditional jobs was essentially unchanged for 2005 and 2015, while the alternative work arrangement level increased by 9.4 million.[65]

- Gallup measured the percent of workers with "good jobs" defined as "30+ hours per week for an employer who provides a regular paycheck." The ratio was around 42% during 2010 and rose to close to 48% during 2016 and 2017. This was measured between 2010 and July 31, 2017, after which Gallup discontinued routinely measuring it.[66]

Persons with multiple jobs[edit]

The BLS reported that in 2017, there were approximately 7.5 million persons age 16 and over working multiple jobs, about 4.9% of the population. This was relatively unchanged from 2016. About 4 million (53%) worked a full-time primary job and part-time secondary job.[67] A 2020 study based on a Census Bureau survey estimated a higher share of multiple jobholders, with 7.8% of persons in the U.S. working multiple jobs as of 2018; the study found that this percentage has been trending upward during the past twenty years and that earnings from second jobs are, on average, 27.8% of a multiple jobholder's earnings.[68]

Other measures[edit]

The U.S. Federal Reserve tracks a variety of labor market metrics, which affect how it sets monetary policy. One "dashboard" includes nine measures, only three of which had returned to their pre-crisis (2007) levels as of June 2014.[69][70] The Fed also publishes a "Labor market conditions index" that includes a score based on 19 other employment statistics.[71][72]

Pace of recovery[edit]

Research indicates recovery from financial crises can be protracted relative to typical recessions, with lengthy periods of high unemployment and substandard economic growth.[73][74] Compared against combined financial crises and recessions in other countries, the U.S. employment recovery following the 2007–2009 recession was relatively fast.[75]

Effect of COVID-19 on increasing unemployment in 2020[edit]

The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic has had a deep impact on the rate of unemployment in the United States. The World Economic Forum predicts a possible rise in the unemployment rate to 20%, a figure unseen since the Great Depression.[76] The United States Congress has passed laws to provide unemployment benefits, such as the Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act, 2020, the Families First Coronavirus Response Act, and the CARES Act. On May 8, 2020, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that 20.5 million non-farm jobs were lost and the unemployment rate rose to 14.7 percent in April.[21] In mid-July 2020 marked the 17th week in a row that unemployment claims topped 1 million. The total unemployment claims filed since the beginning of the pandemic have moved up to 51 million, and the situation is still not optimistic since the complete reopening keeps being postponed.[77] A record 4.3 million people (2.9% of the workforce) quit their jobs in August which is the highest quit rate since the report began in late 2000.[78]

Women and marginalized individuals were particularly vulnerable to job loss during the COVID-19 pandemic.[79] This loss was surprising because women and minoritized people made up the majority of “essential” workers throughout COVID-19.[80] This division is most likely due to racism and sexism in the labor market, especially during recessions.[81][82] Gezici and Ozay (2020) found that, during COVID-19, Black women were more than 4% more likely to be unemployed than White men, while Hispanic women were a little over 5% more likely.[80] Even when an employee worked in a telecommutable job, Black and Hispanic women were more likely to be laid off from their job than White men.[80]

The effects of gender hierarchies were exacerbated during the height of COVID-19.[83] Women's unemployment was impacted more than men's, which is not the case during typical recessions.[79] Mothers were likely to suffer from unemployment for several reasons, including daycare closures, household structures, and job flexibility based on gender.[79] Among married couples, women are more likely to provide childcare than men even when they both work full time.[79] This means that daycare closures disproportionately affected mothers because they were more likely to be expected to take care of their children. While most parents struggled, single mothers were most negatively impacted, partly because single-mother households make up 21% of all households in the United States as compared to only 4% of single-father households.[79] Additionally, mothers were more affected than fathers because men are more likely to have flexible jobs, which allowed them to telecommute. 28% of men work in jobs where they are able to telecommute often, but only 22% of women work in these jobs.[79] Women were at greater risk of contracting COVID-19 in critical (or essential) job positions and more likely to be let go because their work was less flexible.[79]

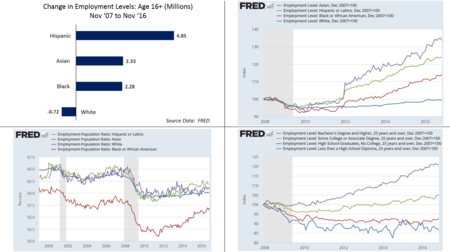

Demographics and employment trends[edit]

Employment trends can be analyzed by any number of demographic factors individually or in combination, such as age, gender, educational attainment, and race. A major trend underlying the analysis of employment numbers is the aging of the white workforce, which is roughly 70% of the employment total by race as of November 2016. For example, the prime working age (25–54) white population declined by 4.8 million between December 2007 and November 2016, roughly 5%, while non-white populations are increasing. This is a major reason why non-white and foreign-born workers are increasing their share of the employed. However, white prime-age workers have also had larger declines in labor force participation than some non-white groups, for reasons not entirely clear. Such changes may have important political implications.[85]

Age[edit]

- The 2007–2009 recession resulted in the number employed falling across all age groups except those aged 55 and over, which continued to increase steadily. Those aged 16–19 were hit the hardest, with the number employed falling nearly 30% from pre-crisis levels, while other groups under 55 fell 5–10%. While the number employed in the 25–34 age group recovered to its pre-crisis (December 2007) level by January 2014 and continued to slowly rise, several under age 55 groups remained below pre-crisis levels as of May 2016.[86]

- Unemployment rates for all age groups rose during the crisis, with the 16–24 year group rising from around 10% during 2007 to peak at 19.5% in 2010, before falling back to 10% by May 2016.[87][88][89][90]

Gender[edit]

- Men accounted for at least 7 of 10 workers who lost jobs during the 2007–2009 recession, according to Bureau of Labor Statistics data.[91] Men aged 25–54 have seen their labor force participation rate fall at all education levels for decades, although the decline was much more severe for those with less than a college education.[84] As of September 2016, seven million US men between 25 and 54 were neither employed nor looking for work.[92] These men tend to be younger, single, non-parents, and less educated. School, disability, level of education, incarceration, and a shift in industry mix away from traditionally male jobs like construction are among potential contributing factors.[93]

- An estimated 40% of the prime working-age men not in the labor force report having pain that prevents them from working.[94]

- The 2022 findings showed nearly half of unemployed U.S. men "have a criminal conviction by age 35, which makes it harder to get a job."[95]

Education[edit]

- Unemployment rates historically are lower for those groups with higher levels of education. For example, in May 2016 the unemployment rate for workers over 25 years of age was 2.5% for college graduates, 5.1% for those with a high school diploma, and 7.1% for those without a high school diploma. Unemployment rates roughly doubled for all three groups during the 2008–2009 period, before steadily falling back to approximately their pre-crisis levels as of May 2016.[96] The recovery has also favored the more educated in terms of employment and job creation. One study indicated that nearly all the 11.6 million net jobs created between 2010 and January 2016 were filled by those with at least some college education. Only 80,000 net jobs were created for those with a high school education or less.[97]

- Employment levels have risen proportionally to educational attainment. From December 2007 (pre-crisis) to June 2016, the number of persons employed changed as follows: Bachelor's degree or higher +21%; some college or associate degree +4%; High school diploma only −9%; and less than high school diploma −14%.[98] Labor force participation rates have also fallen more for men aged 25–54 with lower levels of education, as part of a long-term trend in lower labor force participation for men in that age group.[99]

Race[edit]

- In recent decades, Asians had the lowest unemployment rate as a racial group, followed by whites, Hispanics, and blacks.[100] The New York Times reported some of the causes and consequences of higher black unemployment in February 2018: "Even at the low of 6.8 percent recorded in December [2017] — it climbed back to 7.7 percent in January — the unemployment level for black Americans would qualify as a near crisis for whites. And the relative gains have not erased disparities in opportunity and pay. A tight labor market alone can't undo a legacy of unequal school funding, residential segregation or the disproportionate rate of incarceration for black Americans. Nor can it reverse the gradual shift of well-paying jobs from inner cities to mostly white suburbs. Studies have found that discrimination in hiring and pay persists even in good economic times, making parity an elusive goal."[101]

- The unemployment rate for African Americans rose from 7.6% in August 2007 to a peak of 17.3% in January 2010, before falling back to 8.2% by May 2016. For Latinos over the same periods, the rates were 5.5%, 12.9% and 5.6% respectively. For Asians, the rates were 3.4%, 8.4%, and 3.9%.[102][103]

- Whites saw their employment levels fall more than non-whites over the 2007–2016 period, as a relatively larger number of white persons moved out of the prime working age (25–54) and into retirement. The number of white workers fell by approximately 700,000 from November 2007 (pre-crisis) to November 2016, while the number of workers of other races rose. Hispanics added approximately 4.9 million (+24%), Asian 2.3 million (+34%), and African Americans 2.3 million (+14%).[104] These racial disparities may have helped the Trump campaign with the white working class voters in 2016.[105] While the age 25–54 white population fell about 5% from November 2007 to November 2016, which would correspond with a declining number of whites employed, whites also had a larger decline in the employment to population ratio than non-whites.[85]

- The unemployment rate among African Americans is usually twice that of whites, while Hispanics are between the two rates.[106][107][108][109]

Native- or foreign-born[edit]

BLS statistics indicate foreign-born workers have filled jobs dis-proportionally to their share in the population.

- From 2000 to 2015: 1) Foreign-born represented 33% of the aged 16+ population increase, but represented 53% of the labor force increase and 59% of the employment increase; 2) The number of native-born employed increased by 5.6 million (5%) while the number of foreign-born employed increased by 8.0 million (47%); and 3) Labor force participation declined more for native-born (5 percentage points) versus foreign-born (2 percentage points).[110][111]

- Comparing December 2007 (pre-crisis) to June 2016, the number of employed foreign-born is up 13.3%, while the number of native-born employed is up 2.1%.[112]

Incarceration[edit]

- The average annual weeks of work for ex-offenders are reduced by 5 weeks relative to a 42-week baseline, resulting in a 12% decrease in employment.

- Decline in employment for those who spent time in either jail or prison was 9.7% for young white men, 15.1% for young black men, and 13.7% for young Hispanic men.[114]

- At the community level, local levels of incarceration have been found to have negative spillover effects on local labor markets (particularly in urban areas with higher proportions of Black residents), suggesting that carceral institutions can have indirect dampening effects on local employment.[115]

Causes of unemployment[edit]

There are a variety of domestic, foreign, market and government factors that impact unemployment in the United States. These may be characterized as cyclical (related to the business cycle) or structural (related to underlying economic characteristics) and include, among others:

- Economic conditions: The U.S. faced the subprime mortgage crisis and resulting recession of 2007–2009, which significantly increased the unemployment rate to a peak of 10% in October 2009. The unemployment rate fell steadily thereafter, returning to 5% by December 2015 as economic conditions improved.

- Demographic trends: The U.S. has an aging population, which is moving more persons out of the labor force relative to the civilian population. This has resulted in a long-term downward trend in the labor force participation rate that began around 2000, as the Baby Boomer generation began to retire.

- Level of education: Historically, as educational attainment rises, the unemployment rate falls. For example, the unemployment rate for college graduates was 2.4% in May 2016, versus 7.1% for those without a high school diploma.[96]

- Technology trends, with automation replacing workers in many industries while creating jobs in others.

- Globalization and sourcing trends, with employers creating jobs in overseas markets to reduce labor costs or avoid regulations.

- International trade policy, which has resulted in a sizable trade deficit (imports greater than exports) since the early 2000s, which reduces GDP and employment relative to a trade surplus.

- Immigration policy, which affects the nature and number of workers entering the country.

- Monetary policy: The Federal Reserve conducts monetary policy, adjusting interest rates to move the economy towards a full employment target of around a 5% unemployment rate and 2% inflation rate. The Federal Reserve has maintained near-zero interest rates since the 2007–2009 recession, in efforts to boost employment. It also injected a sizable amount of money into the economy via quantitative easing to boost the economy. In December 2015, it raised interest rates for the first time moderately, with guidance that it intended to continue doing if economic conditions were favorable.

- Fiscal policy: The Federal government has reduced its budget deficit significantly since the 2007–2009 recession, which resulted from a combination of improving economic conditions and recent steps to reduce spending and raise taxes on higher income taxpayers. Reducing the budget deficit means the government is doing less to support employment, other things equal.

- Unionization: The ratio of persons represented by unions has fallen consistently since the 1960s, weakening the power of labor (workers) relative to capital (owners). This is due to a combination of economic trends and policy choices.[118]

- A trend towards more workers in the "gig" or access economy, in alternative (part-time or contract) work arrangements rather than full-time; the percentage of workers in such arrangements rose from 10.1% in 2005 to 15.8% in late 2015. This implies all of the net employment growth in the U.S. economy (about 9 million jobs between 2005 and 2015) occurred in alternative work arrangements, while the number in traditional jobs slightly declined.[65][119][120]

Fiscal and monetary policy[edit]

Employment is both cause and response to the economic growth rate, which can be affected by both government fiscal policy (spending and tax decisions) and monetary policy (Federal Reserve action.)

Fiscal policy[edit]

The U.S. ran historically large annual debt increases from 2008 to 2013, adding over $1 trillion in total national debt annually from fiscal year 2008 to 2012. The deficit expanded primarily due to a severe financial crisis and recession. With a U.S. GDP of approximately $17 trillion, the spending implied by this deficit comprises a significant amount of GDP. Keynesian economics argues that when the economic growth is slow, larger budget deficits are stimulative to the economy. This is one reason why the significant deficit reduction represented by the fiscal cliff was expected to result in a recession.[121][122]

However, the deficit from 2014 to 2016 was in line with historical average, meaning it was not particularly stimulative. For example, CBO reported in October 2014: "The federal government ran a budget deficit of $486 billion in fiscal year 2014...$195 billion less than the shortfall recorded in fiscal year 2013, and the smallest deficit recorded since 2008. Relative to the size of the economy, that deficit—at an estimated 2.8 percent of gross domestic product (GDP)—was slightly below the average experienced over the past 40 years, and 2014 was the fifth consecutive year in which the deficit declined as a percentage of GDP since peaking at 9.8 percent in 2009. By CBO's estimate, revenues were about 9 percent higher and outlays were about 1 percent higher in 2014 than they were in the previous fiscal year."[123]

As part of the economic policy of Barack Obama, the United States Congress funded approximately $800 billion in spending and tax cuts via the February 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act to stimulate the economy. Monthly job losses began slowing shortly thereafter. By March 2010, employment again began to rise. From March 2010 to September 2012, over 4.3 million jobs were added, with consecutive months of employment increases from October 2010 to December 2015. As of December 2015, employment of 143.2 million was 4.9 million above the pre-crisis peak in January 2008 of 138.3 million.[124]

Monetary policy[edit]

The U.S. Federal Reserve (the Fed) has a dual mandate to achieve full employment while maintaining a low rate of inflation. U.S. Federal Reserve interest rate adjustments (monetary policy) are important tools for managing the unemployment rate. There may be an economic trade-off between unemployment and inflation, as policies designed to reduce unemployment can create inflationary pressure, and vice versa. Debates regarding monetary policy during 2014–2015 centered on the timing and extent of interest rate increases, as a near-zero interest rate target had remained in place since the 2007–2009 recession. Ultimately, the Fed decided to raise interest rates marginally in December 2015.[125] The Fed describes the type of labor market analyses it performs in making interest rate decisions in the minutes of the Federal Open Market Committee, its policy governing body, among other channels.[126]

The U.S. Federal Reserve has taken significant action to stimulate the economy after the 2007–2009 recession. The Fed expanded its balance sheet significantly from 2008 to 2014, meaning it essentially "printed money" to purchase large quantities of mortgage-backed securities and U.S. treasury bonds. This bids up bond prices, helping keep interest rates low, to encourage companies to borrow and invest and people to buy homes. It planned to end its quantitative easing in October 2014 but was undecided on when it might raise interest rates from near record lows. The Fed also tied its actions to its outlook for unemployment and inflation for the first time in December 2012.[127]

Political debates[edit]

Liberal position[edit]

Liberals typically argue for government action or partnership with the private sector to improve job creation. Typical proposals involve stimulus spending on infrastructure construction, clean energy investment, unemployment compensation, educational loan assistance, and retraining programs. Liberals historically supported labor unions and protectionist trade policies. During recessions, liberals generally advocate solutions based on Keynesian economics, which argues for additional government spending when the private sector is unable or unwilling to support sufficient levels of economic growth.[128][129]

Fiscal conservative position[edit]

Fiscal conservatives typically argue for market-based solutions, with less government restriction of the private sector. Typical proposals involve deregulation and income tax rate reduction. Conservatives historically have opposed labor unions and encouraged free-trade agreements. Conservatives generally advocate supply-side economics.[128]

Poll data[edit]

The affluent are much less inclined than other groups of Americans to support an active role for government in addressing high unemployment. Only 19% of the wealthy say that Washington should ensure that everyone who wants to work can find a job, but 68% of the general public support that proposition. Similarly, only 8% of the rich say that the federal government should provide jobs for everyone able and willing to work who cannot find a job in private employment, but 53% of the general public thinks it should. A September 2012 survey by The Economist found those earning over $100,000 annually were twice as likely to name the budget deficit as the most important issue in deciding how they would vote than middle- or lower-income respondents. Among the general public, about 40% say unemployment is the most important issue while 25% say that the budget deficit is.[130]

A March 2011 Gallup poll reported: "One in four Americans say the best way to create more jobs in the U.S. is to keep manufacturing in this country and stop sending work overseas. Americans also suggest creating jobs by increasing infrastructure work, lowering taxes, helping small businesses, and reducing government regulation." Further, Gallup reported that: "Americans consistently say that jobs and the economy are the most important problems facing the country, with 26% citing jobs specifically as the nation's most important problem in March." Republicans and Democrats agreed that bringing the jobs home was the number one solution approach, but differed on other poll questions. Republicans next highest ranked items were lowering taxes and reducing regulation, while Democrats preferred infrastructure stimulus and more help for small businesses.[3]

Further, U.S. sentiment on free trade has been turning more negative. An October 2010 Wall Street Journal/NBC News poll reported that: "[M]ore than half of those surveyed, 53%, said free-trade agreements have hurt the U.S. That is up from 46% three years ago and 32% in 1999." Among those earning $75,000 or more, 50% now say free-trade pacts have hurt the U.S., up from 24% who said the same in 1999. Across party lines, income, and job type, 76–95% of Americans surveyed agreed that "outsourcing of production and manufacturing work to foreign countries is a reason the U.S. economy is struggling and more people aren't being hired".[131]

The Pew Center reported poll results in August 2012: "Fully 85% of self-described middle-class adults say it is more difficult now than it was a decade ago for middle-class people to maintain their standard of living. Of those who feel this way, 62% say "a lot" of the blame lies with Congress, while 54% say the same about banks and financial institutions, 47% about large corporations, 44% about the Bush administration, 39% about foreign competition and 34% about the Obama administration."[132]

2008–2009 debates[edit]

The debate around the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA), the approximately $800 billion stimulus bill passed due to the subprime mortgage crisis, highlighted these views. Democrats generally advocated the liberal position and Republicans advocated the conservative position. Republican pressure reduced the overall size of the stimulus while increasing the ratio of tax cuts in the law.

These historical positions were also expressed during the debate around the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008, which authorized the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP), an approximately $700 billion bailout package (later reduced to $430 billion) for the banking industry. The initial attempt to pass the bill failed in the House of Representatives due primarily to Republican opposition.[133] Following a significant drop in the stock market and pressure from a variety of sources, a second vote passed the bill in the House.

2010–present debates[edit]

Creating American Jobs and Ending Offshoring Act[edit]

Senator Dick Durbin proposed a bill in 2010 called the "Creating American Jobs and Ending Offshoring Act" that would have reduced tax advantages from relocating U.S. plants abroad and limited the ability to defer profits earned overseas. However, the bill was stalled in the Senate primarily due to Republican opposition. It was supported by the AFL–CIO but opposed by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce.[134][135]

The Congressional Research Service summarized the bill as follows: "Creating American Jobs and Ending Offshoring Act—Amends the Internal Revenue Code to: (1) exempt from employment taxes for a 24-month period employers who hire an employee who replaces another employee who is not a citizen or permanent resident of the United States and who performs similar duties overseas; (2) deny any tax deduction, deduction for loss, or tax credit for the cost of an American jobs offshoring transaction (defined as any transaction in which a taxpayer reduces or eliminates the operation of a trade or business in connection with the start-up or expansion of such trade or business outside the United States); and (3) eliminate the deferral of tax on income of a controlled foreign corporation attributable to property imported into the United States by such corporation or a related person, except for property exported before substantial use in the United States and for agricultural commodities not grown in the United States in commercially marketable quantities."[136]

American Jobs Act[edit]

President Barack Obama proposed the American Jobs Act in September 2011, which included a variety of tax cuts and spending programs to stimulate job creation. The White House provided a fact sheet which summarized the key provisions of the $447 billion bill.[137] However, neither the House nor the Senate has passed the legislation as of December 2012. President Obama stated in October 2011: "In the coming days, members of Congress will have to take a stand on whether they believe we should put teachers, construction workers, police officers and firefighters back on the job...They'll get a vote on whether they believe we should protect tax breaks for small business owners and middle-class Americans, or whether we should protect tax breaks for millionaires and billionaires."[138]

Fiscal cliff[edit]

During 2012, there was significant debate regarding approximately $560 billion in tax increases and spending cuts scheduled to go into effect in 2013, which would reduce the 2013 budget deficit roughly in half. Critics argued that with an employment crisis, such fiscal austerity was premature and misguided.[139] The Congressional Budget Office projected that such sharp deficit reduction would likely cause the U.S. to enter recession in 2013, with the unemployment rate rising to 9% versus approximately 8% in 2012, costing over 1 million jobs.[121][122] The fiscal cliff was partially addressed by the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012.

Tax policy[edit]

Individual income taxes[edit]

It is unclear whether lowering marginal income tax rates boosts job growth, or whether increasing tax rates slows job creation. This is due to many other variables that impact job creation. Economic theory suggests that (other things equal) tax cuts are a form of stimulus (they increase the budget deficit)[140] and therefore create jobs, much like spending. However, tax cuts as a rule have less impact per additional deficit dollar than spending, as a portion of tax cuts can be saved rather than spent. Since income taxes are primarily paid by higher income taxpayers (the top 1% pay less than 40% of it) and these taxpayers tend to save a higher portion of any incremental dollars returned to them via tax cuts than lower income taxpayers, income tax cuts are a less effective form of stimulus than payroll tax cuts, infrastructure investment, and unemployment compensation.[141][142]

The historical record indicates that marginal income tax rate changes have little impact on job creation, economic growth or employment.[143][144][145]

- During the 1970s, marginal income tax rates were far higher than subsequent periods and the U.S. created 19.6 million net new jobs.

- During the 1980s, marginal income tax rates were lowered and the U.S. created 18.3 million net new jobs.

- During the 1990s, marginal income tax rates rose and the U.S. created 21.6 million net new jobs.

- From 2000 to 2010, marginal income tax rates were lowered due to the Bush tax cuts and the U.S. created no net new jobs. The 7.5 million created 2000–2007 represent slow job growth by historical standards.

- President Obama raised income tax rates on the top 1% via partial expiration of the Bush tax cuts in January 2013. He also raised payroll taxes on the top 5% as part of the Affordable Care Act at that time. Despite these tax increases, average monthly job creation increased from 179,000 in 2012 to 192,000 in 2013 and 250,000 in 2014.[146]

The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP) wrote in March 2009: "Small business employment rose by an average of 2.3 percent (756,000 jobs) per year during the Clinton years, when tax rates for high-income filers were set at very similar levels to those that would be reinstated under President Obama's budget. But during the Bush years, when the rates were lower, employment rose by just 1.0 percent (367,000 jobs)."[147] CBPP reported in September 2011 that both employment and GDP grew faster in the seven-year period following President Clinton's income tax rate increase of 1993, than a similar period after the Bush tax cuts of 2001.[148]

Corporate income taxes[edit]

Conservatives typically argue for lower U.S. tax income rates, arguing that it would encourage companies to hire more workers. Liberals have proposed legislation to tax corporations that offshore jobs and to limit corporate tax expenditures.

U.S. corporate after-tax profits were at record levels during 2012 while corporate tax revenue was below its historical average relative to GDP. For example, U.S. corporate after-tax profits were at record levels during the third quarter of 2012, at an annualized $1.75 trillion.[149] U.S. corporations paid approximately 1.2% GDP in taxes during 2011. This was below the 2.7% GDP level in 2007 pre-crisis and below the 1.8% historical average for the 1990–2011 period.[150] In comparing corporate taxes, the Congressional Budget Office found in 2005 that the top statutory tax rate was the third highest among OECD countries behind Japan and Germany. However, the U.S. ranked 27th lowest of 30 OECD countries in its collection of corporate taxes relative to GDP, at 1.8% vs. the average 2.5%.[151]

Solutions for creating more U.S. jobs[edit]

A variety of options for creating jobs exist, but these are strongly debated and often have tradeoffs in terms of additional government debt, adverse environmental impact, and impact on corporate profitability.[152] Examples include infrastructure investment, tax reform, healthcare cost reduction, energy policy and carbon price certainty, reducing the cost to hire employees, education and training, deregulation, and trade policy. Another suggestion is to have the government become the employer of last resort.[153] A job guarantee would maintain labor market stability and real full employment just as it is responsible for the stability of the financial sector.[154] Authors Bittle & Johnson of Public agenda explained the pros and cons of 14 job creation arguments frequently discussed, several of which are summarized below by topic. These are hotly debated by experts from across the political spectrum.[155]

Infrastructure investment[edit]

Many experts advocate infrastructure investment, such as building roads and bridges and upgrading the electricity grid. Such investments have historically created or sustained millions of jobs, with the offset to higher state and federal budget deficits. In the wake of the 2008–2009 recession, there were over 2 million fewer employed housing construction workers.[155] The American Society of Civil Engineers rated U.S. infrastructure a "D+" on their scorecard for 2013, identifying an estimated $3.6 trillion in investment ideas by 2020.[156]

CBO estimated in November 2011 that increased investment in infrastructure would create between 1 and 6 jobs per $1 million invested; in other words, a $100 billion investment would generate between 100,000 and 600,000 additional jobs. President Obama proposed the American Jobs Act in 2011, which included infrastructure investment and tax breaks offset by tax increases on high income earners.[157] However, it did not receive sufficient support in the Senate to receive a floor vote. During late 2015, the House and Senate, in rare bipartisan form, passed the largest infrastructure package in a decade, costing $305 billion over five years, less than the $478 billion in Obama's initial request. He signed the Fixing America's Surface Transportation Act into law in December 2015.[158]

Tax policy[edit]

Lowering the costs of workers also encourages employers to hire more. This can be done via reducing existing Social Security or Medicare payroll taxes or by specific tax incentives for hiring additional workers. CBO estimated in 2011 that reducing employers' payroll taxes (especially if limited to firms that increase their payroll), increasing aid to the unemployed, and providing additional refundable tax credits to lower-income households, would generate more jobs per dollar of investment than infrastructure.[159]

President Obama reduced the Social Security payroll tax on workers during the 2011–2012 period, which added an estimated $100 billion to the deficit while leaving these funds with consumers to spend. The U.S. corporate tax rate is among the highest in the world, although U.S. corporations pay among the lowest amount relative to GDP due to loopholes. Reducing the rate and eliminating loopholes may make U.S. businesses more competitive, but may also add to the deficit.[155] The Tax Policy Center estimated during 2012 that reducing the corporate tax rate from 35% to 20% would add $1 trillion to the debt over a decade, for example.[160]

Lower healthcare costs[edit]

Businesses are faced with paying the significant and rising healthcare costs of their employees. Many other countries do not burden businesses, but instead tax workers who pay the government for their healthcare. This significantly reduces the cost of hiring and maintaining the work force.[155]

Energy policy and carbon price certainty[edit]

Various studies place the cost of environmental regulations in the thousands of dollars per employee. Americans are split on whether protecting the environment or economic growth is a higher priority. Regulations that would add costs to petroleum and coal may slow the economy, although they would provide incentives for clean energy investment by addressing regulatory uncertainty regarding the price of carbon.[155]

President Obama advocated a series of clean energy policies during June 2013. These included: Reducing carbon pollution from power plants; Continue expanding usage of clean energy; raising fuel economy standards; and energy conservation through more energy-efficient homes and businesses.[161]

Employment policies and the minimum wage[edit]

Advocates of raising the minimum wage assert this would provide households with more money to spend, while opponents recognize the impact this has on businesses', especially small businesses', ability to pay additional workers. Critics argue raising employment costs deters hiring. During 2009, the minimum wage was $7.25 per hour, or $15,000 per year, below poverty level for some families.[155] The New York Times editorial board wrote in August 2013: "As measured by the federal minimum wage, currently $7.25 an hour, low-paid work in America is lower paid today than at any time in modern memory. If the minimum wage had kept pace with inflation or average wages over the past nearly 50 years, it would be about $10 an hour; if it had kept pace with the growth in average labor productivity, it would be about $17 an hour."[164] The real value of the federal minimum wage in 2022 dollars has decreased by 46% since its inflation-adjusted peak in February 1968. The minimum wage would be $13.46 in 2022 dollars if its real value had remained at the 1968 level.[162]

President Obama advocated raising the minimum wage during February 2013: "The President is calling on Congress to raise the minimum wage from $7.25 to $9 in stages by the end of 2015 and index it to inflation thereafter, which would directly boost wages for 15 million workers and reduce poverty and inequality...A range of economic studies show that modestly raising the minimum wage increases earnings and reduces poverty without jeopardizing employment. In fact, leading economists like Lawrence Katz, Richard Freeman, and Laura Tyson and businesses like Costco, Wal-Mart, and Stride Rite have supported past increases to the minimum wage, in part because increasing worker productivity and purchasing power for consumers will also help the overall economy."[165]

The Economist wrote in December 2013: "A minimum wage, providing it is not set too high, could thus boost pay with no ill effects on jobs...America's federal minimum wage, at 38% of median income, is one of the rich world's lowest. Some studies find no harm to employment from federal or state minimum wages, others see a small one, but none finds any serious damage."[166]

The U.S. minimum wage was last raised to $7.25 per hour in July 2009.[167] As of December 2013, there were 21 states with minimum wages above the Federal minimum, with the State of Washington the highest at $9.32. Ten states index their minimum wage to inflation.[168]

The CBO reported in February 2014 that increasing the minimum wage to $10.10 per hour between 2014 and 2016 would reduce employment by an estimated 500,000 jobs, while about 16.5 million workers would have higher pay. A smaller increase to $9.00 per hour would reduce employment by 100,000, while about 7.6 million workers would have higher pay.[169]

Regulatory reform[edit]

Regulatory costs on business start-ups and going concerns are significant. Requiring laws to have sunset provisions (end-dates) would help ensure only worthwhile regulations are renewed. New businesses account for about one-fifth of new jobs added. However, the number of new businesses starting each year dropped by 17% after the recession. Inc. magazine published 16 ideas to encourage new startups, including cutting red tape, approving micro-loans, allowing more immigration, and addressing tax uncertainty.[155]

Education policy[edit]

Education policy reform could make higher education more affordable and more attuned to job needs. Unemployment is considerably lower for those with a college education. However, college is increasingly unaffordable. Providing loans contingent on degrees focused on fields with worker shortages such as healthcare and accounting would address structural workforce imbalances (i.e., a skills mismatch).[155] Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen stated in 2014: "Public funding of education is another way that governments can help offset the advantages some households have in resources available for children. One of the most consequential examples is early childhood education. Research shows that children from lower-income households who get good-quality pre-Kindergarten education are more likely to graduate from high school and attend college as well as hold a job and have higher earnings, and they are less likely to be incarcerated or receive public assistance."[170]

Without the development of vastly different and innovative training methods and strategies, unemployment will rise in both blue collar and white collar sections of the US labor force due to the use of AI and other new technologies in increasingly automated workplaces. Latham and Humbert (2018) stated that when technological advances allow for an automated replacement of a position's essential job functions, the worker will be displaced, as the worker's skill set has become obsolete. The essential job functions are a critical element when determining the likelihood a job will be negatively impacted by automation or AI. “Skills that can easily be standardized, codified, or routinized are most likely to be automated.” (Latham & Humberd, 2018, p. 2).[171]

To counter these trends emphasis must be placed on achieving higher return on investment from the US Department of Education. “Curriculums-from grammar school to college-should evolve to focus less on memorizing facts and more on creativity and complex communication. Vocational schools should do a better job of fostering problem-solving skills and helping students work alongside robots.” (Orszag & Tanenhaus, 2015, p. 14).[172] By refocusing the education system to foster creativity as well as problem solving and critical thinking skills, people entering the US workforce would have valuable and sought after skills. People in the US need to evaluate if as a nation, enough is being done to ensure young people entering the workforce and the current workforce have the necessary skills to weather this massive transition to a more automated world.

Income inequality[edit]

The union movement has declined considerably, one factor contributing to more income inequality and off-shoring. Reinvigorating the labor movement could help create more higher-paying jobs, shifting some of the economic pie back to workers from owners. However, by raising employment costs, employers may choose to hire fewer workers.[155][A]

Trade policy[edit]

Creating a level playing field with trading partners could help create more jobs in the U.S. Wage and living standard differentials and currency manipulation can make "free trade" something other than "fair trade." Requiring countries to allow their currencies to float freely on international markets would reduce significant trade deficits, adding jobs in developed countries such as the U.S. and Western Europe.[155]

Long-term unemployment[edit]

CBO reported several options for addressing long-term unemployment during February 2012. Two short-term options included policies to: 1) Reduce the marginal cost to businesses of adding employees; and 2) Tax policies targeted towards people most likely to spend the additional income, mainly those with lower income. Over the long-run, structural reforms such as programs to facilitate re-training workers or education assistance would be helpful.[174]

President's Council on Jobs and Competitiveness[edit]

President Obama established the President's Council on Jobs and Competitiveness in 2009. The Council released an interim report with a series of recommendations in October 2011. The report included five major initiatives to increase employment while improving competitiveness:

- Measures to accelerate investment into job-rich projects in infrastructure and energy development;

- A comprehensive drive to ignite entrepreneurship and accelerate the number and scale of young, small businesses and high-growth firms that produce an outsized share of America's new jobs;

- A national investment initiative to boost jobs-creating inward investment in the United States, both from global firms headquartered elsewhere and from multinational corporations headquartered here;

- Ideas to simplify regulatory review and streamline project approvals to accelerate jobs and growth; and,

- Steps to ensure America has the talent in place to fill existing job openings as well as to boost future job creation.[175]

Government as the employer of last resort[edit]

The government could also become the employer of last resort, just as central banks are the lenders of last resort.[176][177][178][179] A job guarantee would maintain labor market stability and could establish full employment.[180] This would introduce a shock absorber into the labor market. Full employment might also gain wider support among the electorate than a basic income policy.[181]

Analytical perspectives[edit]

Analyzing the true state of the U.S. labor market is very complex and a challenge for leading economists, who may arrive at different conclusions.[183] For example, the main gauge, the unemployment rate, can be falling (a positive sign) while the labor force participation rate is falling as well (a negative sign). Further, the reasons for persons leaving the labor force may not be clear, such as aging (more people retiring) or because they are discouraged and have stopped looking for work.[184] The extent to which persons are not fully utilizing their skills is also difficult to determine when measuring the level of underemployment.[185]

A rough comparison of September 2014 (when the unemployment rate was 5.9%) versus October 2009 (when the unemployment rate peaked at 10.0%) helps illustrate the analytical challenge. The civilian population increased by roughly 10 million during that time, with the labor force increasing by about 2 million and those not in the labor force increasing by about 8 million. However, the 2 million increase in the labor force represents the net of an 8 million increase in those employed, partially offset by a 6 million decline in those unemployed. So is the primary cause of improvement in the unemployment rate due to: a) increased employment of 8 million; or b) the increase in those not in the workforce, also 8 million? Did the 6 million fewer unemployed obtain jobs or leave the workforce?

Labor market recovery following 2007–2009 recession[edit]

CBO issued a report in February 2014 analyzing the causes for the slow labor market recovery following the 2007–2009 recession. CBO listed several major causes:

- "To a large degree, the slow recovery of the labor market reflects the slow growth in the demand for goods and services, and hence gross domestic product (GDP). CBO estimates that GDP was 7½ percent smaller than potential (maximum sustainable) GDP at the end of the recession; by the end of 2013, less than one-half of that gap had been closed. With output growing so slowly, payrolls have increased slowly as well—and the slack in the labor market that can be seen in the elevated unemployment rate and part of the reduction in the rate of labor force participation mirrors the gap between actual and potential GDP."

- "Of the roughly 2 percentage-point net increase in the rate of unemployment between the end of 2007 and the end of 2013, about 1 percentage point was the result of cyclical weakness in the demand for goods and services, and about 1 percentage point arose from structural factors; those factors are chiefly the stigma workers face and the erosion of skills that can stem from long-term unemployment (together worth about one-half of a percentage point of increase in the unemployment rate) and a decrease in the efficiency with which employers are filling vacancies (probably at least in part as a result of mismatches in skills and locations, and also worth about one-half of a percentage point of the increase in the unemployment rate)."

- "Of the roughly 3 percentage-point net decline in the labor force participation rate between the end of 2007 and the end of 2013, about 1½ percentage points was the result of long-term trends (primarily the aging of the population), about 1 percentage point was the result of temporary weakness in employment prospects and wages, and about one-half of a percentage point was attributable to unusual aspects of the slow recovery that led workers to become discouraged and permanently drop out of the labor force."

- "Employment at the end of 2013 was about 6 million jobs short of where it would be if the unemployment rate had returned to its prerecession level and if the participation rate had risen to the level it would have attained without the current cyclical weakness. Those factors account roughly equally for the shortfall."[186]

Comparison of employment recovery across recessions and financial crises[edit]

One method of analyzing the impact of recessions on employment is to measure the period of time it takes to return to the pre-recession employment peak. By this measure, the 2008–2009 recession was considerably worse than the five other U.S. recessions from 1970 to present. By May 2013, U.S. employment had reached 98% of its pre-recession peak after approximately 60 months.[187] Employment recovery following a combined recession and financial crisis tends to be much longer than a typical recession. For example, it took Norway 8.5 years to return to its pre-recession peak employment after its 1987 financial crisis and it took Sweden 17.8 years after its 1991 financial crisis. The U.S. is recovering considerably faster than either of these countries.[74]

[edit]

The ratio of full-time workers was 86.5% in January 1968 and hit a historical low of 79.9% in January 2010. There is a long-term trend of gradual reduction in the share of full-time workers since 1970, with recessions resulting in a decline in the full-time share of the workforce faster than the overall trend, with partial reversal during recovery periods. For example, as a result of the 2007–2009 recession, the ratio of full-time employed to total employed fell from 83.1% in December 2007 to a trough of 79.9% in January 2010, before steadily rising to 81.6% by April 2016. Stated another way, the share of part-time employed to total employed rose from 16.9% in December 2007 to a peak of 20.1% in January 2010, before steadily falling to 18.4% in April 2016.[62]

There is a trend towards more workers in alternative (part-time or contract) work arrangements rather than full-time; the percentage of workers in such arrangements rose from 10.1% in 2005 to 15.8% in late 2015. This implies all of the net employment growth in the U.S. economy (9.1 million jobs between 2005 and 2015) occurred in alternative work arrangements, while the number in traditional jobs slightly declined.[65][119]

What job creation rate is required to lower the unemployment rate?[edit]

Estimates[edit]

Estimates vary for the number of jobs that must be created to absorb the inflow of persons into the labor force, to maintain a given rate of unemployment. This number is significantly affected by demographics and population growth. For example, economist Laura D'Andrea Tyson estimated this figure at 125,000 jobs per month during 2011.[188]

Economist Paul Krugman estimated it around 90,000 during 2012, mentioning also it used to be higher.[189] One method of calculating this figure follows, using data as of September 2012: U.S. population 314,484,000 x 0.90% annual population growth x 63% of population is working age x 63% work force participation rate / 12 months per year = 93,614 jobs/month. This approximates the Krugman figure.

Wells Fargo economists estimated the figure around 150,000 in January 2013: "Over the past three months, labor force participation has averaged 63.7 percent, the same as the average for 2012. If the participation rate holds steady, how many new jobs are needed to lower the unemployment rate? The steady employment gains in recent months suggest a rough answer. The unemployment rate has been 7.9 percent, 7.8 percent and 7.8 percent for the past three months, while the labor force participation rate has been 63.8 percent, 63.6 percent and 63.6 percent. Meanwhile, job gains have averaged 151,000. Therefore, it appears that the magic number is something above 151,000 jobs per month to lower the unemployment rate."[190] Reuters reported a figure of 250,000 in February 2013, stating sustained job creation at this level would be needed to "significantly reduce the ranks of unemployed."[191]

Federal Reserve analysts estimated this figure around 80,000 in June 2013: "According to our analysis, job growth of more than about 80,000 jobs per month would put downward pressure on the unemployment rate, down significantly from 150,000 to 200,000 during the 1980s and 1990s. We expect this trend to fall to around 35,000 jobs per month from 2016 through the remainder of the decade."[192]

Empirical data[edit]

During the 41 months from January 2010 to May 2013, there were 19 months where the unemployment rate declined. On average, 179,000 jobs were created in those months. The median job creation during those months was 166,000.[193]

International labor force size comparisons[edit]

The U.S. civilian labor force was approximately 155 million people during October 2012.[6] This was the world's third largest, behind China (795.5 million) and India (487.6 million). The entire European Union employed 228.3 million.[194]

Effect of disability recipients on labor force participation measures[edit]

The number of people receiving Social Security disability benefits (SSDI) increased from 7.1 million in December 2007 to 8.7 million in April 2012, a 22% increase. Recipients are excluded from the labor force. Economists at JPMorgan Chase & Co. and Morgan Stanley estimated this explained as much as 0.5 of the 2.0 percentage point decline in the U.S. labor-force participation rate during the period.[195]

Effects on health and mortality[edit]

Unemployment can have adverse health effects. One study indicated that a 1% increase in the unemployment rate can increase mortality among working-aged males by 6%. Similar effects were not noted for women or the elderly, who had lower workforce attachment. The mortality increase was mainly driven by circulatory health issues (e.g., heart attacks).[196] Another study concluded that: "Losing a job because of an establishment closure increased the odds of fair or poor health by 54%, and among respondents with no preexisting health conditions, it increased the odds of a new likely health condition by 83%. This suggests that there are true health costs to job loss, beyond sicker people being more likely to lose their jobs."[197] Extended job loss can add the equivalent of ten years to a person's age.[198]

Studies have also indicated that worsening economic conditions can be associated with lower mortality across the entire economy, with slightly lower mortality in the much larger employed group offsetting higher mortality in the unemployed group. For example, recessions might include fewer drivers on the road, reducing traffic fatalities and pollution.[198]

Effects of healthcare reform[edit]

CBO estimated in December 2015 that the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (also known colloquially as "Obamacare") would reduce the labor supply by approximately 2 million full-time worker equivalents (measured as a combination of persons and hours worked) by 2025, relative to a baseline without the law. This is driven by the law's health insurance coverage expansions (e.g., subsidies and Medicaid expansion) plus taxes and penalties. With access to individual marketplaces, fewer persons are dependent on health insurance offered by employers.[199]

Job growth projections 2016–2026[edit]

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) reported on October 24, 2017, its projections of job growth by industry and job type over the 2016–2026 period. Healthcare was the industry expected to add the most jobs, driven by demand from an aging population. The top three occupations were: personal care aides with 754,000 jobs added or a 37% increase; home health aids with 425,600 or 47%; and software developers at 253,400 or 30.5%.[200]

BLS also reported that: "About 9 out of 10 new jobs are projected to be added in the service-providing sector from 2016 to 2026, resulting in more than 10.5 million new jobs, or 0.8 percent annual growth. The goods-producing sector is expected to increase by 219,000 jobs, growing at a rate of 0.1 percent per year over the projections decade." BLS predicted that manufacturing jobs would decline by over 700,000 over that period.[200]

Obtaining data[edit]

Monthly jobs reports[edit]

U.S. employment statistics are reported by government and private primary sources monthly, which are widely quoted in the news media. These sources use a variety of sampling techniques that yield different measures.

- The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) provides a monthly "Employment Situation Summary." For example, BLS reported for December 2012 that: "Nonfarm payroll employment rose by 155,000 in December, and the unemployment rate was unchanged at 7.8 percent...Employment increased in health care, food services and drinking places, construction, and manufacturing."[201]

- Automatic Data Processing (ADP) also provides a "National Employment Report." For the December 2012 period, ADP reported a 215,000 non-farm payroll increase.[202]

Several secondary sources also interpret the primary data released.

- The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities provides a monthly "Statement" on the BLS Situation Summary. The CBPP wrote in January 2013: "[December 2012] is the 34th straight month of private-sector job creation, with payrolls growing by 5.3 million jobs (a pace of 157,000 jobs a month) since February 2010; total nonfarm employment (private plus government jobs) has grown by 4.8 million jobs over the same period, or 141,000 a month. Total government jobs fell by 546,000 over this period, dominated by a loss of 395,000 local government jobs."[203]

Federal Reserve Database (FRED)[edit]