Hugo W. Koehler

Hugo W. Koehler | |

|---|---|

| |

| Birth name | Hugo William Koehler |

| Born | July 19, 1886 St. Louis, Missouri, US |

| Died | June 17, 1941 (aged 54) New York City, US |

| Buried | Berkeley Memorial Cemetery, Middletown, Rhode Island |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1909–1929 (20 Years) |

| Rank | |

| Commands | USS Piscataqua (AT-49) |

| Battles/wars | World War I Russian Civil War |

| Awards | Navy Cross (1920) World War I Victory Medal with Submarine Chaser Clasp (1920) Officer, Legion of Honor (France) Order of St. Vladimir (Russia), 4th Class with swords and bow (1920) Order of St. Stanislaus (Russia), 2d Class with swords (1920) Order of St. Anna (Russia), 2d Class with swords (1920) Officer, Order of the Crown (Belgium) Navy Sharpshooter's Badge, Expert (1908) |

| Signature |  |

Hugo William Koehler (July 19, 1886 – June 17, 1941) (pronounced [ˈkøːlɐ]) was a United States Navy commander, secret agent and socialite. Following the First World War, he served as an Office of Naval Intelligence and State Department operative in Russia during its civil war, and later as naval attaché to Poland. He was rumored to be the illegitimate son of the Crown Prince of Austria and to have assisted the Romanovs in fleeing Russia following the revolution of 1917. He was awarded the Navy Cross for his service during World War I and was the step-father of United States Senator Claiborne Pell (1918–2009).

Early life and family history

[edit]

Hugo W. Koehler was born on July 19, 1886, in St. Louis, Missouri, and named after a paternal uncle. His father, Oscar C. Koehler (1857–1902), was a first-generation German-American and second-generation St. Louis and Davenport, Iowa brewer and entrepreneur.[1] Although it was privately rumored for much of his life that Hugo was the illegitimate son of Rudolf, Crown Prince of Austria, who is generally believed to have died with his teenage mistress, Baroness Mary Vetsera, in a murder-suicide pact in January 1889 (the "Mayerling incident"), no corroborating evidence of this ancestry has been established. The speculation was fueled by a few factors: 1) Koehler, who was reputed to be the "wealthiest officer" in the American navy in the 1920s, was apparently the beneficiary of a substantial trust fund. It was further speculated that this trust had been established by the Habsburgs with approval of the Holy See when Hugo Koehler was a child, to provide for his support and maintenance; 2) As a child, Hugo made several European visits with his paternal grandfather, Heinrich (Henry) Koehler Sr. (1828-1909), where he was introduced to aristocracy and elites;[2] and 3) Koehler had the distinctive Habsburg chin.[3]

Ironically, in 1945, The New York Times published a story that a German lithographer by the name of "Hugo Koehler", following his death at the age of 93, was revealed to be Archduke Johann Salvator of Austria, son of Leopold II, Grand Duke of Tuscany and a member of the Imperial Austrian Habsburg family. Johann had been a witness to the tragic events at Mayerling in 1889. Rudolf, unsatisfied in his marriage to Stephanie, daughter of Leopold II of Belgium had found romance with Mary, the younger daughter of a Hungarian earl. Taking her along on a party to his hunting lodge at Mayerling, the young woman soon became excessively animated and sought to interject herself into court politics and intrigue. Rudolf snubbed her for this, and in a fit of rage, the 17-year old baroness smashed a bottle of champagne over Rudolf's head, killing him. Hearing the fracas and then a gunshot, Johann and other revelers on a nearby balcony, rushed into the salon to discover that Rudolf's valet had avenged his master's death with a single, fatal gunshot to Mary Vetsera. The event was immediately covered-up, and the story of a murder-suicide was fabricated. Enemies of both Rudolf and Johann, began spreading innuendo that Johann was implicated in Rudolf's death. When Emperor Franz Joseph questioned the young archduke about these rumors in 1889, Johan became furious and broke his sword over his knee. Tearing the epaulets and military decorations off his uniform, Johann threw them at the feet of the emperor, and renounced his right to the throne until such time as he might be cleared of the false accusations. The Emperor, indignant at Johan's actions, sentenced him to lose his princely rights and succession for twenty years. Johan then left the country and assumed his new life and the name "John Orth". Orth and his wife, an actress, were believed lost at sea in a shipwreck off Cape Horn in 1890 and were declared dead in absentia in 1911.[4] The 1945 story of Johan's (Orth's) survival has not been established as true.

Koehler's grandfather, Heinrich, was born in the state of Hesse in Germany. A master-brewer trained at Mainz, he had immigrated to America at the age of twenty-one, quickly making his way to St. Louis, where German-Americans accounted for nearly one-third the population of 78,000 in 1850. Working his way up to foreman at the Lemp brewery, by 1851 Koehler had saved enough capital to start his own brewery, and moved 225 miles upriver on the Mississippi to Fort Madison, Iowa, where he purchased a small, but established brewery and introduced lager beer to the surrounding area. Around 1863, Heinrich, who now went by "Henry", leased his brewery to his father-in-law, and moved back to St. Louis where he bought a partnership interest in the Excelsior Brewery from his younger brother, Casper (1835–1910). By then the city's population had swelled to more than 300,000 and the brothers aimed to increase beer production and sell to the thousands of Federal troops stationed in the city environs. While the brewery flourished, the brothers' relationship did not. In 1871, Henry sold his interest to Casper and moved his family upriver to Davenport, Iowa. Davenport was then part of the Tri-cities metropolitan area, including the neighboring riverfront cities of Moline and Rock Island, Illinois. A year later, he bought the established Arsenal Brewery with his brother-in-law, Rudolph Lange. The business was also known as Koehler and Lange, after its owners. With a growing, largely Germanic immigrant population that regarded beer as a staple, Davenport had cheaper operating costs than St. Louis, including river and rail transportation with caves along the river where the beer could be stored. The area proved ideal to expand the business. Weathering obstacles, including the rising Temperance Movement, in 1884 the partners were industry forerunners when they introduced a non-alcoholic beer, called Mumm, derived from a German word meaning disguise or mask.[5][6]

In 1875, seventeen-year old Oscar Koehler, the oldest of Henry's seven children, obtained a passport to study in Germany. After completing studies at the Academy of Brewing in Worms, he entered the University of Leipzig where he obtained a doctorate in chemistry four years later. Returning to America, he was exceptionally trained for the brewing industry. After a brief stint at his father's brewery in Davenport, Oscar moved to St. Louis where he became secretary of the Henry Koehler Brewing Assoc., a business his father established in 1880. The following year, Oscar was joined by his younger brother, Henry Jr. (1863–1912), and by 1883 the business was sold to the St. Louis Brewing Assoc. As that business was winding down, the Koehler brothers were setting up their successor business, "The Sect Wine Company", which Oscar and his father had started preparing for in 1880 on a stock offering of $135,000 ($3.4 mil. in 2010). With the stated purpose "to deal in nothing but strictly pure wines, recognizing that he who appreciates a fair article will willingly pay a fair price to obtain it", the business occupied a two-story distillery and winery of 80,000 square feet at 2814-24 South Seventh Street in St. Louis. Production of the company's signature champagne "Koehler's Sect" and its still wines was overseen by experienced winemakers from Rheims, France, and marketed by a staff of travelling salesmen.[7]

The Koehlers' expansion into the winemaking business, particularly the popular "Koehler's Sect", enhanced both their wealth and prestige in the St. Louis business community. Their marriages and social activities further solidified their elite standing. In 1885, Oscar married Mathilda Lange (1866–1947), daughter of William Lange, president of the National Bank of St. Louis. In 1888, two years after his marriage to Mathilda, Oscar joined the Germania Club, an exclusive club open only to St. Louis residents who had graduated from German universities. Oscar was one of only sixty-one members.[6] In 1897, Henry Jr. married the California actress Margaret Craven in a San Francisco society wedding that was publicized in the New Yorkand Los Angeles Times, the former writing that Craven had married "Henry Koehler, a rich brewer of St. Louis"[8] and the latter reporting that "Miss Craven is a professional actress and is noted for her beauty. The groom is 35 years old and a millionaire."[9] Oscar and Henry Koehler Jr., remained in the wine business until 1890. In 1887, they were joined by their younger brother, Hugo (1868–1939), who had originally moved to the city to attend St. Louis Medical College. In January 1890, the brothers began their most successful venture in the series of business ventures that ultimately amassed them millions of dollars, when they organized the American Brewing Company (A.B.C.) with $300,000 ($7.42 million in 2010) in capital. Constructed on the site of the Sect Wine Company and other Koehler businesses on South Seventh Street in St. Louis, the huge plant was praised for its architectural design and function, employing the latest in brewing technology including the largest copper brew kettles ever made. As with their champagne and wines, the Koehler's mission statement was "to produce beers of the highest class only, and to obtain patronage by furnishing only such an article." Before long, the Koehlers' beer, particularly their A.B.C. Bohemian was available through wholesale distributors (typically German-Americans) in locations as far away as Albuquerque, New Mexico, and Birmingham, Alabama. Ultimately, the brewery expanded into foreign distribution, including Egypt, the Philippines and Japan, before closing in 1940, never recovering from the negative business impact caused by Prohibition.[10]

In 1894, Oscar left the American Brewing Company and St. Louis, to move back to Davenport, where he took over his father's interest in the Arsenal Brewery (Koehler and Lange). The change was prompted by Henry's decision to take an extended trip to Europe, where he stayed for two years. In 1895, Oscar commissioned the architect Friedrich Clausen to construct a 5-bedroom, 3,700 sq. ft. Queen Anne residence at 817 W. 7th Street, overlooking the bluffs of the Mississippi River on Davenport's Gold Coast.[11][6] Young Hugo lived his childhood and adolescence with wealth and privilege. The oldest of six children (Elise (1887-1971), Herbert (1888-1945), Otillie (1894- 1975), Eda (1900-1958), and Hildegarde (1901-1926)), his childhood memories were of preferential treatment over his brother and sisters. Never being disciplined and having the best pony and cart, engendered the notion in Hugo that he was "different". A prankster in his youth, he delighted in trying the limits of his grandfather's patience. A wine collector, Henry would organize wine-tasting dinners for his friends, who were asked to identify the wine and vintage after trying it. Once, Hugo decided to substitute inferior wines, believing his grandfather and his friends could not tell the difference. Hiding behind the curtains, Hugo was surprised to see his grandfather's reaction on sampling the wine, as he rose to apologize to his guests that there "must have been some mistake". When the boy confessed to the deceit later, his grandfather was more hurt than angry. For him, there were certain lines that no gentleman would cross.[12] Hugo journeyed to England with his grandfather, where he was introduced to the physiologist John Scott Haldane, statesman-naturalist Lord Grey of Fallodon and Empress Elisabeth. In Austria, the boy was introduced to the court of Emperor Franz Josef. As Koehler put it years later, "After all that, water pistols were not very interesting."[13]

On one European summer vacation, Henry asked the youth what he might do with his life. Hugo responded that he would like to be a philosopher, or a Jesuit or a naval officer. His grandfather responded that the boy was already somewhat of a philosopher and observed that for his grandson, the Roman Catholic priesthood would involve "more disadvantages than advantages." He concluded, "if you want to be a naval officer, you will have to get some education first, for the Naval Academy gives you only a training."[14]

Following the consolidation trend in the brewing industry, in October 1894, Hugo's father, Oscar, merged the Arsenal Brewery with four other breweries into a single firm, Davenport Malting Company, becoming president of the new concern. The economy of scale enabled the firm to bar outside competition that could not compete with the low production costs. In 1895, the company built a new brewery with modern equipment and expansive storage facilities on the site of the former Lehrkind Brewery on West Second Street. Its product line included Davenport Malt Standard (keg beer), Muenchener (both keg and bottled), and Pale Export (bottled). Strong sales of Pale Export and the Muenchener beers provided the revenue for the addition of a state-of-the-art ice plant in 1896. In the spring of 1897, the company expanded its plant again, adding a new racking room, wash house, and hop storage area. By 1898 sales were so strong that the company increased its capital stock from $50,000 to $150,000 ($1.36 million to $4.07 million in 2010) that provided the funding for a malt house. The Davenport Malting Company was the second largest in the state of Iowa, employing sixty men and with fifteen distribution agencies scattered throughout the state. The plant had a capacity of 100,000 barrels, reportedly selling over 50,000 barrels in 1899. Unfortunately, Oscar Koehler did not live to see the success of the brewery continue into the 20th century, largely due to his effort. After months of declining health, in 1902 he died at St. Louis, where he had gone for treatment of Bright's Disease, a form of kidney failure. Following his father's death, fifteen-year old Hugo's education was undertaken by his grandfather, Henry, who sent the boy to the prestigious Phillips Exeter Academy in New Hampshire for his senior year in 1902.[15]

Harvard and Annapolis

[edit]-

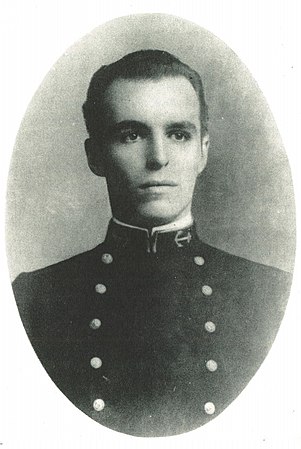

Midshipman Hugo W. Koehler, USN, about 1909

-

Midshipman Hugo W. Koehler, USN, in the 1909 Lucky Bag

Koehler attended Harvard College for his freshman and sophomore years, before entering the United States Naval Academy in 1905.[16] In the summer between Harvard and Annapolis, Koehler gave a preview of his brazen ability to bluff that would serve him well in war-ravaged Germany and Russia fifteen years later. Hungry and broke, he and three friends drove to New York City from Cambridge, Massachusetts, after changing three tires along the way. Arriving in the city, Koehler suggested a trip to the theater. Marching up to the ticket window, he barked, "I say, gimmi mi tickets." The ticket-man politely asked "What name?" and Koehler gave his last name. Knowing the ticket-man would not find any tickets under "Koehler" and that the ticket agencies were closed, Koehler fumed, "call Tyson and see about it." Koehler's ploy worked, and the ticket agent offered them choice tickets that Koehler condescendingly took. Coming out of the theater later and still famished, the group headed up Fifth Avenue and bumped into one of Koehler's best friends who staked them for a meal. "We paid for the tickets the next day, for we thought we might want to work the same game again."[17] Koehler wrote in a letter shortly after arriving at Annapolis, "Everybody in town, officers, professors, and 'cits', (fellow midshipmen) thinks it most extraordinary that I should go into the Academy ... they say that for a man who has tasted life at Harvard, it is a mighty hard thing to buckle down to the exact routine [and] discipline... in practice here [but] I am going to do my very best here, to make up for my past, and to do something for my future and for the future of the ones I love." What in the eighteen-year old Koehler's past he felt that he had to make up for is unclear.[18] The stories of his arrival at Annapolis vary only in their "outrageousness": that he arrived with a horse and valet; another recounts a horse and cook. While at the academy, he maintained a pied-à-terre with a steward, where hot food was always available to all comers. He was known for his success as a ladies' man, often sending American Beauty roses to the objects of his affection.[19] At Annapolis, Koehler qualified as a rifle expert shot in 1908, the highest level, and was awarded the Navy Sharpshooter's Badge. Somewhat presciently, the page entry for Koehler in the Naval Academy annual Lucky Bag contains two quotes from Shakespeare that were placed by the editors and intended to capture his essence, "The glass of fashion and the mold of form, the observed of all observers", and "I am not in the roll of common men." The yearbook editors' words are equally descriptive, "A capable, conceited man who cannot be bluffed." During the winter before Koehler graduated from Annapolis, his grandfather passed away. Before he died, Henry revealed the purported secret of Hugo's birth. He told Hugo that his father was not Oscar Koehler, but Rudolph, crown prince of Austria. There is no record of how Hugo responded to this shocking disclosure. But for the rest of his life, Koehler searched for some proof of this. He revealed the story to only his closest confidants, and speculated that the truth was locked in the archives of the Vatican, that could not be opened for 99-years, until 1987, long after his death.[3]

Under the terms of Oscar Koehler's will, the Koehler residence on Seventh Street passed to his wife, Mathilda Koehler, with the remainder of the estate held in trust by the executors, who were to invest the money and pay the interest to Mathilda, on a semi-annual basis for the rest of her life. Following her death, the remaining trust was to be divided equally among the children when they came of age.[6] This would not explain the mysterious "Austrian trust" with Hugo Koehler as beneficiary, or the inexplicable source of income that gave him the reputation as the "richest officer" in the U.S. Navy. "[K]oehler seemed to possess a beneficent parachute that popped open precisely when he needed it."[17]

Koehler had been taught to speak German and French, along with English. He spoke British English with a slight German accent, from his Midwest roots. During his four-years at Annapolis, Koehler's performance varied wildly. In May 1908, he ranked 12th in seamanship, 16th in the three separate categories of math, mechanics, and ordinance; 93rd in efficiency; and 161st in marine engines. He had probably enjoyed the bumps along the road to 215 demerits. One time, he and his roommate, future rear admiral Ernest Ludolph Gunther (1887–1948) fought so savagely they both ended up in the hospital. Amazingly, the Lucky Bag reported, Gunther "managed to room with Hugo for four years and still maintains his equilibrium of mind." Ultimately, Koehler finished in the exact middle of his class.[19]

Navy career

[edit]Yangtze Patrol

[edit]

Koehler graduated from the Naval Academy in June 1909 and as a passed midshipman was attached to the armored cruiser USS New York (ACR-2) on October 29 of that year. During his time aboard, New York made two cruises to the Mediterranean Sea and steamed to the Philippines. New York was renamed Saratoga in February 1911. In August, he was attached to the gunboat USS Villalobos (PG-42) which was assigned to the Yangtze River Patrol in China "on the broad principle of extending American protection to wherever this country's nationals resided for Gold, Glory or Gospel," observed Koehler. Fifty years later, Villalobos was the inspiration for the fictional USS San Pablo in Richard McKenna's novel and later movie, The Sand Pebbles.[20][21][22] But in 1911 when Koehler shipped aboard, it was only months before the "Last Emperor", Pu-Yi abdicated the throne in January 1912. Before joining Villalobos, Koehler visited the battlefields of Port Arthur, where Russia had battled Japan six years earlier in the Russo-Japanese War. In Villalobos's logbook for October 11, 1911, Koehler wrote, "At 0800 Mids. H.W. Koehler, U.S. Navy, boarded the Chinese gunboat to obtain further information regarding the situation at Wuchang... Wuchang... was entirely in the hands of rebels and there was no possibility of communication with the American residents." Two days later, the log continues, "Midshipman Koehler attended a conference of the consular body at which the Japanese rear admiral Reijiro Kawashima presided, the meeting having been called to consider communications of the rebel commander in chief, in which he stated the aims of the rebel party, and offered to send troops to protect the foreign concessions. The offer was not accepted... at 1815 sent ashore two Colt automatic guns to American consulate in order to facilitate landing of armed party.... Incendiary fires in Wuchang throughout the night."

By mid-November, the Yangtze and all of China was in control of the rebels and "the gun-boaters could get back to the normal routine of golf, billiards, tennis and light conversation." Koehler was promoted to ensign on March 28, 1912, to date from June 5, 1911. Koehler was equally at-ease and engaging with the unwashed masses as he was with the aristocracy of his time. He wrote to his mother about a "wonderful tiger hunting expedition" in Mongolia that he made in November 1912 when he was on leave. The twenty-six year old ensign was already accepted as an equal by the likes of his hunting partners: Count Pappenheim, friend to King Edward VII; Baron Cottu, financier of the Canton-Hankow-Peking railway[23] and Count Riccardo Fabbricotti, "the best looking man in Europe, the wildest and greatest rake", married to Theodore Roosevelt's cousin, Cornelia Roosevelt Scovel.[24] Koehler described Fabbricotti's wife as "perfectly lovely, adores him and understands him not at all", which could equally describe the woman Koehler married fifteen years later.[25]

Koehler was detached from Villalobos and to Saratoga (ex- USS New York), the Asiatic Fleet flagship, on January 2, 1913, Commander Henry A. Wiley, commanding. Koehler was already coveting the billet of naval attaché to Moscow, when he was assigned as translator for an extended tour of Asian ports by Rear Admiral Reginald F. Nicholson, Commander in Chief, Asiatic Fleet (CINCAF), including Saigon, the French port and Qingdao, the German port. As Koehler wrote, "I have been studying hard, for I intend to learn Russian. So many of my friends are Russian, and I like the Russians, so ... you see I am still thinking of my billet as attaché."[26]

On January 26, 1914, Ensign Koehler was given command of the USS Piscataqua, a fleet tug based at Olongapo Naval Station, Philippine Islands. Under him were three other ensigns and forty enlisted men.[27][28] At one point during his command, Congress failed to pass a naval budget appropriation and Koehler paid the men on his ship and several others from his own pocket. As another eccentricity, Koehler kept a menagerie on his ship. Tragically, his pet boa constrictor swallowed his small spotted deer. Both died when the deer's sharp hooves pierced the snake's side. During the week of June 1–6, 1914, Lt. Cdr. Lewis Coxe, commanding the Naval Station at Olangapo, ordered Koehler to tow a naval coal barge that Koehler subsequently deemed unseaworthy after his ship started the tow and discovered the barge was taking on water. Koehler returned to port; however, Coxe insisted that he carry out the order. Koehler did, the barge and its $10,000 cargo capsized, Coxe was court-martialed, found guilty of neglect of duty and culpable inefficiency, and Koehler was exonerated.[29][30][31] On June 5, 1914, Koehler was promoted to lieutenant (junior grade).[32] That September, Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels quoted Koehler's commanding officer and said, "This Koehler is very adaptable and possesses a military spirit unusual in one of his rank. At the same time he has produced a smart ship, a contented crew, and the ship in general and the engine room are the cleanest I have ever seen."[26]

Koehler detached from Piscataqua in June 1915, and returned to the Continental United States aboard the SS Chiyo Maru from Yokohama via Honolulu to San Francisco, and listed on the manifest as "Capt. H.W. Koehler".[33] Before sailing from Japan, Koehler used his Germanic looks and "Kaiser Willie" mustache to bait the Japanese into arresting him as a suspected German spy. With no ID card, commonplace for the time, Koehler spent several days in a Japanese jail, happy to learn what the Japanese were interested in, until the U.S. naval attaché, received a cabled description of Koehler from Washington. More than fifteen years before Japanese imperialism blighted Asia, Koehler wrote, "with Japan and things Japanese... I detest them more each day".[34] Returning to the receiving ship at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, Koehler was briefly attached to the battleship USS Michigan (BB-27) with the Atlantic Fleet from September 16,[35] until October 5, 1915, when he was attached to her sister ship USS South Carolina (BB-26). During this time South Carolina operated on the East Coast of the United States, spending summers in maneuvers off Newport, Rhode Island and winters in the Caribbean.[36]

World War One

[edit]Following the United States entry into World War I, Koehler was promoted to lieutenant on June 5, 1917. He detached from South Carolina to serve as an aide to Captain Arthur J. Hepburn, Commander of the Submarine Chaser Division at the New London Navy Yard in Connecticut on January 30, 1918. While in New London he shared an apartment with Lieutenant (j.g.) Harold S. "Mike" Vanderbilt whose family fortune stemmed from the New York Central Railroad. When Vanderbilt left Koehler a note which appointed him "official furniture mover for the house we are about to lease. /s/ H.S. Vanderbilt", Koehler, not to be outdone, replied with a note which described an incident in which Roman political philosopher Cicero was appointed as garbage remover of Rome by his enemies in order to discredit and discourage him. Quoting Cicero's reply to his malefactors, "If the office will not bring me honor, I will bring honor to the office," Koehler quipped, "Rome was very badly in need of a garbage collector. Cicero became the most efficient garbage collector that Rome had ever known, and as a result Cicero was made consul and his fame has descended down through the generations. /s/ Hugo W. Koehler"[37]

On June 15, 1918, Koehler followed Captain Hepburn when he was ordered to Europe to take command of the Submarine Chaser Division for the Irish Sea headquartered in Queenstown, Ireland. Koehler was promoted to temporary lieutenant commander on July 1, 1918, and given command of a detachment of submarine chasers.[38] Vanderbilt, who arranged for Koehler's entry into the upper crust of British society, was also ordered to Queenstown. Koehler remained lifelong friends with Vanderbilt, and good-naturedly described his chum as the "boy navigator". Recalling the trans-Atlantic passage to Ireland, Koehler noted that Vanderbilt carried around a sextant "everywhere, and even slept with it I have no doubt... However, he really did take a sight on the way over, and I am creditably informed (by no less person than himself) that the sight actually showed our position as somewhere in the North Atlantic, and not on the top of a mountain, as is sometimes the case with boy navigators. But at any rate, the captain of the ship did not take his advice too seriously and so we arrived safely."[39] Unlike 1915 Japan, 1918 Ireland welcomed Koehler's Germanic appearance, because it implied anti-Britain, a mistaken assumption that was far from Koehler's actual, lifelong anglophilia. One lieutenant remembered him as "a very Teutonic-looking man and we knew that he went to Sinn Fein meetings, but just who he pretended to be we never knew." Mike Vanderbilt, who rented a mansion with Koehler in Queenstown, watched as he "left the table and a few moments later, I saw him sneaking out the front door in civilian clothes, made up to be ever more Germanic than usual." Sinn Féin meetings were off limits to U.S. personnel.[40] Koehler spent considerable energy and time to study "both sides of the Irish question." He concluded, "But my sympathies are wavering and are now all for the British... But how to satisfy a people split into factions, each faction demanding something different... The Home Rule has its stronghold in the South and is solidly Catholic. The Ulsterites or North Irish party, almost as solidly Protestant, are opposed to Home Rule for the simple reason they realize the minute the South Irish party takes charge, all industries of Ireland—about 95% of which are in the north—will shortly be taxed out of existence.... I have never yet been able to discover just what the Sinn Feiners want, nor has anybody else... Taxes here are much less than in England. Irish per capita representation in Parliament is greater than that of any other country in England. Food is plentiful. There are no food restrictions and the English supply them with more food than they give their own people. And yet they have a hymn of hate for the British no less venomous than the German hymn... The great point of difference between the English and the Irish is after all the English have no sense of humor and the Irish have the keenest sense of humor in the world. It is this difference that makes it impossible for Englishmen to understand Irishmen, and it is an axiom that one must first understand those whom one would govern... One of the most dangerous symptoms lies in the fact that the whole Sinn Féin movement is tinged with the idea of martyrdom, and it seems to derive considerable strength just from the fact of its hopelessness. The only parallel I have ever seen was in the Southern Philippines, where native priests told the Moros that the greatest good that could come of them would be to kill a heathen American and be shot down in turn, for only then would the gods transport them to Seventh Heaven. Irishmen are rapidly getting the same sort of fanaticism and openly declare that they neither fear nor would they regret being shot down for their cause, since every Irishman shot down by the police or soldiery means a distinct gain for Ireland, because 20 men will be inspired by the example of the one who has fallen.... So hurrah for Ireland and the Irish, say I! It's the devil of a country to live in or work in but a fine place to play in. And the Irish? I love them as friends and playmates, but oh! how I'd hate to have them as compatriots or relations."[41]

Writing to his mother, Koehler described as "murder" the roughness of patrols on the Irish Sea, the constant smell of diesel and twenty-four hours of "drifting patrol", without engines so as to avoid detection by German submarines. The subchasers could determine the direction of a submarine, but not the distance, so they operated in a line of three, each independently determining the direction, with the three lines then plotted on a chart. The point of intersection was the location of the sub, which would have moved on by then, necessitating a new trilateration when they reached the last known point, and in that manner "like a hare and hound chase" the subchasers worked in unison with patrol aircraft launched from four airfields on the Irish Coast, that transmitted the location as soon as a wake or sub was sighted. "This cooperation of aircraft with subchasers multiplied the usefulness of both, as subchasers became the ears for the aircraft and aircraft became the eyes for the subchasers," Koehler observed.[42]

He was awarded the Navy Cross in 1920, for his World War I duty, with the following citation: "The Navy Cross is presented to Hugo W. Koehler, Lieutenant Commander, U.S. Navy, for distinguished services in the line of his profession for duty in connection with preparation of submarine chasers for duty in the war zone and subsequently their operation in the Irish Sea and off the coast of Ireland."[43]

Post Armistice England

[edit]

After the Armistice was signed on November 11, 1918, Koehler was detached to the staff of Admiral William S. Sims, commanding U.S. Naval forces in Europe, with headquarters in London. The two months that Koehler spent on Sims' staff were far removed from the rough seas and fumes of the subchasers. "I have landed among the very smart and fashionable and the diplomatic set," he wrote his mother, "many of whom I already knew officially: and on the other hand through Lady Scott (wife of Captain Scott who discovered the South Pole), whom I have known a long time, I see a great deal of men like Bernard Shaw, Arnold Bennett and James Barrie, so I don't get too narrow in my ideas about things English. Mike Vanderbilt's sister, the Duchess of Marlborough, has been chaperoning me very carefully and on two occasions has had me all but married without consulting either me or the lucky girl! Rumors of this may reach you, but you are not to take them seriously. Of course, I always take all lovely women seriously--"[44] Koehler spent Christmas 1918 at the baronial manor house at Cranmore, Somerset, as the guest of Lady Muriel Paget with a party of thirty-seven "diverse personalities" including Arthur Balfour, former Conservative British Prime Minister; Barrie, author of Peter Pan; and Lord Herbert John Gladstone, Liberal British statesman, member of Parliament and first governor general and high commissioner for South Africa. Gladstone, the son of "The Grand Old Man", Prime Minister William Gladstone, remained a close friend of Koehler for fifteen years, and circumspectly countenanced an ongoing affair of similar duration between his much younger wife, Dolly, and Koehler. Over the years of their friendship that lasted until Gladstone's death, his salutations evolved from, "My dear Commander", to "My dear Hugo", to "My dear Old Fellow", to "Dear Old Boy".[45] In a letter to Mathilda, Koehler described the festivities, "One evening at dinner, James Barrie was told to construct the most wonderful play he had ever written. He did so the following morning; in the afternoon the play was rehearsed, and in the evening it was produced in seven acts, a tremendous success. It was wonderfully clever, for most of the actors had simply to act their own characters. Mr. Balfour took the part of a Foreign Minister; Lord Gladstone took the part of a Colonial Governor (he had just been Governor of South Africa) and I was a dashing (sic!) young naval officer. The result was a screaming farce. We were there five days and were idle not a solitary moment. Almost every day we had a football game in which everybody took part, men, women and children, and indeed it was a lesson in poise to see the splendid way in which the most dignified old statesmen and haughty dowagers dashed about and scrambled in the mud."[46]

The day after Christmas, Koehler returned to Cranmore from a partridge shoot and was captivated by the dinner guests seated on either side of him, the daughters of Thomas Thynne, 5th Marquess of Bath. Recognizing that "two beautiful women at the same time are always a difficulty", Koehler "at once" made the "dreadful decision" and between Lady Emma Margery Thynne (1893–1980) and Lady Alice Kathleen Violet Thynne (1891–1977), chose Emma as the object of his pursuit. The following day, Koehler was scheduled to go to Maiden Bradley to hunt with Sir Edward Seymour, 16th Duke of Somerset. He devised a scheme with the cooperation of his hostess, Lady Paget. Returning from the hunting trip, they would have a tire "puncture" in front of Longleat, the ancestral home of the Marquess of Bath. The enterprising Koehler would present himself at the door and further sojourn with Emma would be his. Koehler showed Balfour and the duke the note of his plan he had scribbled to Lady Paget. They "roared" and asked Koehler what he was going to do about it. "Get them of course", was the response to more laughter. The duke and Koehler made a wager, his gun for the duke's greatcoat, that Koehler would not succeed. Koehler executed his plan, and "lifting the enormous knocker, [to] beat a bold tattoo on a door about the size of the gates of St. Peter's," he was ushered into Longleat. Only then did he discover that while he was hunting, Emma had sent word to Cranmore inviting him to spend the weekend at Longleat, and so his suitcase had been packed and put in his car unbeknownst to him. "At any rate I have the duke's greatcoat. Since then all my weekends save one, when I went back to the old duke, have been spent at Longleat".[47]

While he lost Emma to William Compton, 6th Marquess of Northampton, who married her in 1921, Koehler reflected in a letter to his mother dated February 5, 1919, while embarked on HMS Comus for the northern Scotland anchorage, Scapa Flow, "I shall grieve as much as any Englishman when the old order changes, for I cannot help thinking that when all the land is cut up into small farms and the great estates pass out of existence, England will lose a lot more than she will gain by any improvement that may come from men working their own farms instead of being tenants. For instance, Longleat comprises some 68,000 acres. Of course, that seems a tremendous big corner of a small country like England for one man to own. But no one will ever provide for that land and all the people on it as carefully as have the Thynnes for many generations. It takes 68,000 acres to support it. And those aristocrats of England, they deserve well of their country – they've poured out their blood and their treasure unsparingly in this war. Take the Thynnes, for example. Every one of them did splendidly: the oldest son, Viscount Weymouth (2nd Lt. John Alexander Thynne, 1895–1916), went to France the first week of the war, distinguished himself, and was killed in action a week after he got the Victoria Cross. And the girls saw their job and did it. It was necessary that women, who had never worked before, should go into factories. The quickest way to bring about so revolutionary a change was to make it fashionable. So these girls, with the proudest blood in England in their veins, promptly took jobs in a munition factory. They stuck at it, and for long hours each day, for month upon month, they worked at their lathes with a thousand other men and girls about them. In the meantime, their mother, the Marchioness of Bath, converted her home into a hospital and ran it herself, having asked the government for nothing but medicines – she provided doctors and nurses and all else. So bravo for them, I say! They saw their duty and did it."[48]

Koehler's commanding officer at Queenstown, Captain Hepburn, attended the December 18, 1918 meeting that organized the Allied Naval Armistice Commission. When Hepburn returned to the U.S. in early 1919, Koehler was attached as translator for Vice Admiral Samuel S. Robison, the ranking American representative on the commission. For one month there were dinner parties every night and on weekends at Longleat, before the commission headed to Scapa Flow in early February 1919, where nearly 80 ships of the German High Seas Fleet had been interned while awaiting disposition through peace treaty negotiations. From there the commission headed to various German ports to assess the condition of German warships and merchantmen.[49]

Post-war intelligence gathering

[edit]Following the war, Koehler was part of a navy reconnaissance team sent to report on the Russian Civil War. He met many of the major military figures of both the Bolshevik and White Russian factions, including General Anton Denikin, Lt. General Alexander Kutepov and General (Baron) Pyotr Wrangel, notably taking part in Wrangel's raid into Taurida, where Koehler narrowly escaped capture at Melitopol. He was awarded three of the small number of Russian Imperial military decorations that were distributed during this time[50] and also recommended for award of the Distinguished Service Medal by his commanding officer, Rear Admiral McCully.[51]

Germany

[edit]

Koehler reconnaissanced Germany in 1919, shortly after its defeat in World War I and the German Revolution of 1918–1919, which first brought down the monarchy and then cleared the way for the establishment of the Weimar Republic after supporters of a parliamentary system defeated advocates of a soviet-style council republic. Koehler's instincts were aristocratic but his impulses were proletarian.[52] During his initial six-week inspection tour of various German port cities and towns, beginning with Wilhelmshaven and on to Hamburg, Bremen and Kiel, he observed conditions of both the German capital ships and the general population. "We found the German ships all in a frightful state, both as regards cleanliness and preservation. They had evidently been hastily put out of commission for there was no one on board... The ships that were in commission, as for example the new light cruiser Koenigsberg were also in hopeless condition, although they had large crews on board... As this rabble came out on deck, where we were patiently waiting, the men crowded around us so it was necessary to ask the captain to have them withdraw sufficiently to allow us breathing space... The men moved slowly away and sulked and muttered. We also inspected the destroyers, submarines and the aircraft station. Conditions were everywhere alike: everything unspeakably filthy, no work being done, everything going to rack and ruin..."[53] In his report to Admiral Sims, Koehler wrote, "The one sure thing about the German navy is that it is finished-finished far more effectively than if every officer and man and ship had been sunk. With the exception of U-Boat men, the navy and everyone in it is in disgrace. The U-Boat men were loyal throughout the whole revolution, and are loyal to the central government today, but even they appear ashamed of the navy for many of them wear soldier uniforms. Hardly anywhere does anyone see a sailor in uniform. So thoroughly is the shame of the navy felt that the blue uniform is considered almost a badge of disgrace, and except for the uniforms of men of the few ships still in commission one never sees any blue, although the streets are crowded with men in the forest gray of the infantry."[54] At Wilhelmshaven, he put in "a good many hours" reading newspapers, handbills and political pamphlets distributed by the "Workmen's Council", the Socialists and the civil government, with titles such as, "Tirpitz the Grave Digger of the German Navy". Koehler saw the outcries of the masses expressed in placards that read, "We have a right to something besides work." "We have a right to bread." "Labor, which alone produces wealth, alone has the right to wealth." "No more profit."[55]

"I asked the people about the Kaiser (Wilhelm II), the sum of all their answers was that the Kaiser today, even if not openly popular, nevertheless has a greater hold on the respect and affections of the Germans as a whole than has any other in the Empire. The crown prince is not popular. They say the Kaiser was badly advised, but that after all, no man in Germany has the interests of Germany so close at heart or worked so hard or tirelessly as did the Kaiser. Another idea which is also very widespread is that the great general staff which he reared so carefully became a car of Juggernaut and rolled over him. They all agree that he was weak about the use of gas. They say that he forbade the use of gas, but was later overruled by the militarists. No one thinks that the use of gas was wrong, though quite a number think it was very foolish to start off on a small scale. They argue that if the Kaiser had allowed the use of gas on a tremendous scale, as the general staff wanted to at the beginning, they would have won the war before the allies could have provided themselves with gas masks. It is also said that the kaiser opposed air raids on undefended towns in England, but was overruled by the general staff. I have heard a great many bitter criticisms of the German chemists who could not discover a nonflammable gas for Zeppelins, while American chemists did."[56]

Koehler assessed the two needs of Germany in the few months following the Armistice: food and raw materials. Food to keep her poor people from suffering and actual starvation within weeks, since they had no money to purchase food at profiteer prices, and to keep her workmen out of bolshevism. Raw materials were needed partly for the same reason, to block bolshevism and to help Germany to regain her place in the commercial world and also to repay the enormous war debt saddled on her by the Kaiser and his military advisors. "The Germans are not starved yet, but they are pretty hungry. One sees a good many double chins and paunches still, that is among the men. The women look really emaciated. They have suffered from the food shortage a great deal more than the men. The saddest thing, however; is the suffering among children. They show it markedly. Infant mortality has been very high and still is, though not as bad as in the winter of 1916–17. Meat sells at from 29 to 30 marks a pound, including the bone. To illustrate the scarcity, during an attack of Spartacans in Wilhelmshaven, a horse in a passing cart was shot. Within 20 minutes after it fell, every shred of flesh had been stripped from its bones. This indicates that meat shortage even more plainly than the empty butcher shops do. Grocery shops appear fairly well stocked, but the prices are enormous. Practically everything is rationed, including clothing. Great quantities of potatoes and cabbages are on hand, and, counting the difference in exchange, they can be bought cheaper here than in England. practically no vegetables of any other kind are on hand. No tinned vegetables are obtainable in any of the shops. Fats do not exist. There is an almost total absence of soap. They have a substitute which is said to be very poor. The bread is bad. It is made of wurzel meal, as potatoes cannot be spared for meal. There is very little milk in the country."[57]

Germany's solution to its economic woes would be a massive emigration to the United States that would both create a new market for Germany to revitalize its industrial capacity and facilitate remittances back to Germany as the new immigrants prospered, Koehler believed. Receiving Koehler's report, Admiral Sims replied, "My opinion of the value and the interest of this letter is such that... I have had it mimeographed for circulation among our forces here... I am also sending copies to the O.N.I. (Office of Naval Intelligence) and to certain officers....I should be glad if, as opportunity provides, you would continue similar observations and send them in to headquarters."[58] Koehler's assessment of conditions in Germany were reprinted in American newspapers.[59][60]

Koehler made a follow-up inspection and report from Wilhelmshaven and Kiel on June 16, reporting that "The whole harbor of Kiel was filled with decaying men-of-war. It is almost impossible to conceive how complete is the ruin that comes to men-of-war in just a few months of neglect, for these splendid ships of only six months ago are even now almost beyond recall..." Less than a week after Koehler wrote his report, the German navy in defiance of the terms of the Peace "diktat", scuttled most of its ships interned at Scapa Flow.[61] Reporting from Scapa Flow a week later, Koehler wrote, "All Germany and particularly naval officers are jubilant about the sinking of the German ships at Scapa Flow... Everywhere in Germany I heard the cry against the clause in the peace terms that provides for the trial of the Kaiser and others responsible for the war..."[62] Koehler saw that over-reaching by the other allies, particularly France, would be problematic for the next generation. "In those questions on which the United States has taken a different stand than the Allies, Germans attribute it to a latent friendship for Germany- a friendship somewhat disturbed these last years but that still exists. It is difficult to point out that the attitude of the U.S. is not that of favoring Germany but simply the earnest desire to do the right thing and bring about a peace that does not contain in the very peace terms the germs of another war. That the U.S. took none of the surrendered U-boats is well known in Germany and considered a good omen that the U.S. has no desire to take anything from Germany. Extreme bitterness toward the English seems to be lost in their greater hatred of France. They say France has only one idea of peace- to ruin Germany utterly- and the only thing that can keep France from doing this is the British sense of fair play and this latent friendship from America....A restaurant manager asked the same question that greeted us on all sides: He was surprised when I mentioned it seemed likely the places to which Americans would flock after peace had been declared were the battlefields at Ypres, the Somme, and Château-Thierry, and not the spas of Germany...."[63]

First American Officer in Berlin

[edit]

While newspapers reported that Hugo Koehler was the first American naval officer to enter Germany following the Armistice,[64][65] Koehler did not enter Germany until February 1919. He does have the distinction of being the first American officer to enter Berlin following the signing of the Treaty of Versailles on June 28, 1919, officially ending the war.[66] The Allied Naval Armistice Commission was at Hamburg embarked on the British cruiser, HMS Coventry. The city was under martial law and none of the British officers were interested in going ashore, unlike Koehler and Chief Yeoman Walter Dring, USN (1894–1984). Despite warnings of the danger, and armed with a notebook and pencils, Koehler and Dring sauntered down the gangplank and strode to the Hamburg-American Line pier. pushing through a crowd that was jostling for sugar and cigarettes, the pair were headed towards the main street, when two German military police on a sidecar motorcycle stopped and picked them up for questioning. Brought to German naval headquarters, they were interrogated by Admirals Scheer, Von Hipper and Von Reuter. Koehler explained that Coventry was the first inspection ship to arrive at Hamburg following the treaty and that the British officers preferred to remain on board. The Germans were greatly amused that the British were reluctant to come ashore and gave the American naval spy and his scribe permission to travel to Berlin by night train, provided they remained confined to their compartment. At 7 a.m. the following morning, Koehler and Dring arrived as the first American military to enter Berlin. They flipped a coin to see who would be first off the train, but "both landed on the platform at the same time in a heap". Koehler hailed a cab, an emaciated horse drawing a cart with bare, iron wheels, and directed the driver to the Adlon Hotel, where he reminisced with the owner, Lorenz Adlon (1849–1921) about meeting him in Berlin 25 years earlier with his grandfather, and gave the man two chocolate bars, soap and cigarettes. After breakfast, the duo's sightseeing was interrupted by three policemen who escorted them back to the hotel. With no papers other than their orders from London, they were directed to take the 6 o'clock train out of Berlin. But Koehler had other plans, and instead of going back to Hamburg and HMS Coventry, he took Dring to the best hotel in Düsseldorf. From there they boarded a train to Hanover, then on to Cologne, where Koehler sought out British officers of the Army of Occupation who promptly locked them up as spies. "Hugo looked like the Kaiser with that damn little mustache," complained Dring. When they were released, they took a train to Brussels and then on to Paris, where Koehler told Dring that he was "going to duck for three or four hours before reporting to the embassy." Left to face the Red Cross alone and standing in line for breakfast with other servicemen, Dring was questioned and declared that he had just come from Germany. Red Cross officials disbelieved his story and the MP's believed he was a spy, so Dring was again arrested and continued to go hungry.[67]

Rear Admiral Newton McCully and North Russian Operations

[edit]

When Dring finally got to the American embassy in Paris, officials asked where Koehler was. The roving commander showed up a few days later and wrote his follow-up report on conditions inside Germany. On July 7, the adventure was over and Dring was ordered back to London. Before he left, he introduced Koehler to Rear Admiral McCully, who had recently arrived from Allied operations in North Russia. In Paris, Koehler was assigned as aide to McCully, the senior Navy member of the American Commission to Negotiate Peace.[68] As a lieutenant commander in 1904, McCully had been a military observer embedded with the Imperial Russian Army during the Russo-Japanese War, arriving at the front lines in Manchuria via the Trans-Siberian Railway. Returning to the United States in 1906, McCully had submitted a lengthy report on his findings.[69] In 1914, McCully was assigned as naval attaché at St. Petersburg. By 1916, fluent in Russian and knowledgeable of the fluid political, military and social conditions there, he warned the State Department that food shortages, official corruption and a demoralized populus might soon force Russia out of World War One. In 1917 he witnessed the beginnings of the Russian Revolution. Shortly after this, he was ordered back to sea duty in the Atlantic and promoted to rear admiral in September 1918. Less than a month before the Armistice, McCully was designated as Commander, U.S. Naval Forces in Northern Russia, and read his orders aboard the USS Olympia on October 24, 1918. With Olympia's departure for Scotland on November 8, McCully and a small contingent of officers and bluejackets were the American naval presence for the Allied intervention in the Russian Civil War, the struggle between the Bolsheviks and those who opposed them (often known as the "Reds" and "Whites", respectively).[70] The 8,000 American troops of the American Expeditionary Force Siberia sent by President Woodrow Wilson to Vladivostok to guard the billion-dollar investment of American guns and equipment along the Trans-Siberian railroad and protect the Czech legion tried to remain in a defensive posture. A larger force of British "Tommies", freezing alongside the Czechs, fought among themselves as much as against the Bolsheviki.[71][72][73] The separate 5,000 troop Polar Bear Expedition was sent to Archangel to guard the Murman and Archangel-Vologda railways and Allied supply stockpiles in the vicinity.[74] American military action was deemed admissible only to assist the Czechs in defending themselves against armed Austrian and German prisoners that were attacking them and to steady efforts at self-government by the Russians. American policy was stated on August 3, 1918, the day after the Allied occupation of Archangel, "Whether from Vladivostok or from Murmansk and Archangel, the only present object for which American troops will be employed will be to guard military stores which may subsequently be needed by Russian forces and to render such aid as may be acceptable to the Russians in the organization of their self-defense." No interference with Russian political sovereignty or intervention in her internal affairs was planned.[75] Despite this directive, during their 19 months in Siberia, 189 soldiers of the American Expeditionary Force Siberia died from all causes, including combat. The smaller American North Russia Expeditionary Force experienced 235 deaths from all causes during their nine months embedded during fighting near Archangel.[76] Through March 1919, McCully's men primarily operated ashore from Murmansk and engaged in intelligence gathering and reporting to Admiral Sims in London on the political, financial, military, naval, and economic conditions. McCully reported that the Whites and Allied forces controlled about two-thirds of Archangel province, south to Murmansk and west to the border between Finland and Karelia. Concerning naval conditions there was little to report, for there had been no naval operations, the Bolsheviks not having a deep-water naval presence in North Russia.[77][78] With his familiarity of Russia and its language, unquestionably, McCully was the Navy's top "Russia man".[79] In a report to Admiral Sims in late February, McCully reported that the military situation in the Archangel region was precarious and that Allied forces along both the Archangel-Vologda railway and the Murman railway were insufficient. He urged stationing vessels at both Archangel and Murmansk and providing another to cruise along the 1,600-mile coast and visit other ports. During May through June, the patrol gunboat USS Sacramento (PG-19), protected cruiser USS Des Moines (CL-17) and three Eagle-class patrol boats were detached to McCully, to supplement the Spanish American War-era, steam-schooner USS Yankton that he had taken as his flagship in February.[80][81] By order of the Secretary of the Navy dated June 30, two days after the signing of the peace treaty at Versailles, McCully was detached from his command in Northern Russia and directed to proceed to London.[82] Following the withdrawal of U.S. ground forces from Archangel and its vicinity in July, with a backdrop of deteriorating morale and American public opinion, the last remaining U.S. naval vessel, Des Moines stood out from Archangel on September 14, 1919, and steamed down the Northern Dvina River for Harwich, England, marking the conclusion of American naval operations in North Russia.[83]

-

USS Yankton at Ivanovski Bay, Russia, 1230 a.m., May 1919

-

USS Des Moines in 15 feet of snow and ice, White Sea, Russia, May 19, 1919

-

L to R, Rear Admiral Newton McCully, unknown Russian naval captain, Captain Zachariah Madison, commanding, aboard USS Des Moines, Russia, June 1919

-

Preparing to tow USS Eagle Boat 3 (PE-3), June 1919

-

USS Sacramento at Archangel, Russia, 1919

-

339th US Army Infantry Regiment, at Archangel, May 30, 1919

-

USS Des Moines sailors on parade at Archangel, June 1919

-

Memorial at US Army and Navy cemetery at Archangel, Russia, May 30, 1919

With McCully's "Mission to South Russia"

[edit]

On August 6, Koehler was sent on another fact-finding survey in Germany, where he inspected floating dry docks. Before returning to Paris, he was ordered to London to brief Winston Churchill at the War Office on conditions inside Germany.[84] With the exception of Churchill, the allies had been reluctant to enter the Russian morass. Foreign intervention in the Russian Civil War would not have proceeded without Churchill's persistence. As he warned the House of Commons in March 1919, "Bolsheviks destroy wherever they exist but by rolling forward into fertile areas, like the vampire which sucks the blood from its victim, they gain means of prolonging their own baleful existence."[85] In the spring of 1919, the army of Admiral Alexander Kolchak, organizer of the "White" resistance in Siberia had advanced to the Volga River. The forces of Russian general Yevgeny Miller were fighting the "Reds" as far as Petrograd. From the west, a small army under General Nikolai Yudenich had also advanced on Petrograd, while in South Russia, the forces of General Anton Denikin had begun to advance on Moscow. But by the summer, the advances of all the various White factions, and their fortunes, reversed almost simultaneously, except for those in South Russia that continued to advance into autumn. Seizing the opportunity to fill the void of the departed German army, newly independent Poland occupied parts of Lithuania, eastern Galicia and Ruthenia, before advancing into western Ukraine, where Nestor Makhno, an anarchist with a band of militarist peasants was attacking both Red and White troops. With the governments of Britain and America yielding to public pressure at home and withdrawing their troops from Archangel, Murmansk and Olonets, Miller's troops were left to face the Reds alone, and swift defeat. Yudenitch overreached his advance and the Reds repulsed his forces back to the Baltic states, where they disbanded. To the east, Kolchak's over-extended troops were trounced before they could reach the Volga and began a torturous retreat to Siberia, without supplies and forced to strip corpses for clothes and shoes.

Denikin reached within 200 miles of Moscow, and filled with hubris, debated which horse he would triumphantly ride into the city, but over-extended and with broken supply lines, in October, the Reds pummelled his forces at Oryol and forced him to retreat with his disintegrating army.

Driven southward, his troops surrendered Kharkov to the Bolsheviks on December 13, 1919.[86] By the end of that year, the struggle between the Bolsheviks and the Whites had driven thousands of retreating White Army troops and civilian refugees to the northern shore of the Black Sea and into the Crimean Peninsula, where they could expect no mercy from the Bolsheviks. The Peace Commission concluded on December 10, and while the other American staff members returned to the United States, McCully was ordered to London as a representative on the Commission on Naval Terms. At the suggestion of Admiral Mark L. Bristol, Commander, Naval Forces, Turkish Peninsula, McCully was proposed to lead a special mission for the U.S. State Department with the purpose of keeping the government informed of developments in that region and to protect American lives and interests.[87][88]

On December 23, 1919, Secretary of State Robert Lansing cabled McCully designating him Special Agent for the Department of State and instructing him to proceed with a detachment including Koehler, who was then also fluent in Russian as his second-in-command, and nine other naval officers and enlisted men, "to the south of Russia with a view, first, to make observations and report to this Department upon political and economic conditions in the region visited, and second, to establish informal connection with General Denikin and his associates." ("South of Russia" meaning the area roughly encompassed by Ukraine and Crimea.) Taking a train from Paris to Italy, on New Year's Day 1920, Koehler and McCully sailed aboard the steamer Karlsbad bound for Salonika, Greece. Six days later they arrived at Constantinople. En route through Greece, Koehler characteristically took the opportunity to engage the locals and analyze the economic and social conditions. In a letter to his mother, he showed remarkable astuteness in commenting on the economic imbalance of the Greek economy that led to its debt crisis nearly a century later. "I talked to .... a professor at the University of Athens, [who] spoke at great length about Greek claims to Smyrna. I asked what these claims were and what they were based on. They were all based on historical reasons, he answered but was vague as to the exact historical reasons.... I commented that... what Greece needed was raisins rather than historical reasons-- raisins and olive oil to pay for her tremendous imports being paid for only by loans and paper... But apparently the Greeks believe that there is no need for such mundane things as raisins and olives while loans are plentiful and they can get flour and automobiles for paper money...."[89][90]

Odessa, February 1920

[edit]

Vice Admiral Bristol detached one of the various destroyers in his command, to operate along the northern Black Sea coast to assist the Mission, enabling McCully to continuously maintain mail and radio communication. Bristol dispatched Lt. Hamilton V. Bryan to serve as McCully's agent at Odessa in Ukraine, and he also kept Bristol informed of happenings.[91] On the morning of February 10, 1920, Koehler came ashore at Odessa lighthouse from the destroyer USS Talbot (DD-114) on a mission to evacuate the few American citizens believed still in the city, which had been overrun by the Bolshevik Red Army in the Odessa Operation after General Nikolai Shilling, Denikin's appointed commander of White forces in the Odessa area, had failed to mount any defense and been among the first to evacuate.[92][93] Russian and British mission officers, along with 5,000 refugees were being evacuated by sea under the protection of the British cruiser HMS Ceres.[94] Negotiating his way up from the lighthouse keeper, who was loath to go into the city, to the captain of the Red Guard, Koehler quickly arranged to be taken to meet with General Ieronim Uborevich of the Red Army, the victor of Odessa that had vanquished Denikin's Whites from the town. Repeatedly questioned by a commisar what Entente men-of-war were doing in the harbor and why they had fired on Bolshevik troops, Koehler steadfastly and calmly parried the charges, insisting that no firing had occurred since Talbot anchored in the harbor, that the Americans were there for the sole purpose of evacuating refugees, and that he understood the reason for prior naval gun fire was because Odessa had been occupied by "marauders and thieves" before the Red Army entered. When Uborevich questioned Koehler about American opinion of Bolshevism and its recent victories, Koehler responded that he "had not been in America since the war, so he "did not know American opinion in detail, but that in general, I thought that American opinion was not impressed with the chance of success of any government based on the will of so minute a minority as that of the present Bolshevist regime."[95] Koehler was initially told by Uborevich and a commisar that they would need "word from Moscow" on his request to make contact with the Americans, that might take two or three days. Koehler was able to expertly manipulate around the delay and avoid becoming an extended "guest" of the Reds. When Uborevich asked Koehler what he thought of the recent Red victories, Koehler told him that his impression was that the Red advance was more an example of the weakness of Denikin's forces than the strength of the Red Army. "No one made any comment on this reply and I became very definitely of the opinion that at heart they agreed with me."

Accompanied by a general, orderly and a guard, Koehler first went to the address of Mrs. Annette Keyser (1893–1971), a Russian-born composer, singer and widow of an American citizen. As the grateful woman wrote a few years later to Secretary of the Navy, Edward Denby, "I happened to be sick in bed with pneumonia and tonsillitis, and I wrote a letter to the American mission, imploring them to save me... I could not believe my eyes when I beheld a tall man entering my room dressed in a black cloak, conveyed by two armed Bolshevists. Is it possible? An AMERICAN OFFICER, I exclaimed.... Lt. Cmdr. Hugo W. Koehler-- came close, he said, 'Yes, it is possible; here I am to help you, as I know you are sick." I broke down, crying like a child, and begged the kind officer to take me to America, to my Mother, as I had no one in Odessa but my beloved husband's grave... During the sad scene one of the armed Bolshevists took stations at the door, and the other, evidently knowing the English language, came closer to hear the conversation. Lieutenant Commander Koehler tried to quiet me, explaining that he had orders to take the refugees to Constantinople only. The neighbors hearing this, advised me to remain, as I was too ill to travel. Lieutenant Commander Koehler, also finding this best, advised me to stay.... Thinking that I was in need, he offered me money... and he assured me that I was not in danger, and if he found out that I was, he would come and take me with him. After he left, my friend explained to me that his (Koehler's) life was in danger, as there was no government to be responsible if anything should happen to him.... [I] prayed to be in a position to come to the United States some day in order to find Lieutenant Commander Koehler and to thank him personally and to tell the world that there are still some noble and kind people who will endanger their lives to help a little, weak woman, a mere stranger." The Secretary of the Navy wrote to Koehler that his "chivalrous efforts" were "the kind of service that makes life worthwhile."[96]

From her studio in Los Angeles, California, Annette Keyser recalled a dozen years later, "I was ill with pneumonia at Odessa.... My condition was too serious to permit my removal and Commander Koehler came ashore and with the aid of Capt. [James] Irvine got a promise from the revolutionists that upon my recovery I would be permitted to leave. This I did and was put on board a Turkish steamer and reached Constantinople safely."[97] After Koehler had made arrangements with the Reds to secure Keyser's safety and eventual evacuation to Constantinople, with his Red escort he next visited the addresses of three American men, and determined that two had already made it safely out of Odessa; however, the third was believed to be in the city and "strongly suspected of pro-Bolshevik leanings". Koehler was then taken back to Red headquarters, where he was able to delay his voluntary departure for a day, and make further observations as he walked ten miles through the besieged city. "I entered two food shops and although there was not a great abundance of supplies, both shops had customers buying food. All money is current: Soviet, Romanov, Kerensky, even Denikin army money, in accordance with the decree to the effect that shopkeepers are required to accept every kind of Russian money tendered to them.... Streets of the town were in deplorable condition. Numerous dead horses and dogs were lying about, but I saw no human bodies,... the Americans I was endeavoring to locate lived in widely separated quarters of the town, so I was able to go practically everywhere I wished... I was particularly on the lookout for signs of German influence, German officers or munitions, any trace of German activity, but failed to discover anything...."[98] About a week after Koehler's departure from Odessa, the Bolshevik government sent a long wireless dispatch to President Wilson and the League of Nations, complaining that after "Captain Keller" had left the city and "given [his] word" that he would not fire on the town, "a murderous fire was opened up from [his] entire squadron and hundreds of innocent women and children were killed thereby." As Koehler wrote to his mother about the deceitful fabrication, "And incidentally, although this message described me as a very terrible and very wicked man, I've always been grateful to the Bolsheviks for it, for in light of these tactics I was able to understand many things not clear to me before."[99]

Novorossiysk, March 1920

[edit]

After the fall of Odessa to the Reds, Koehler and McCully returned to Sebastopol and a short visit to the battle front. Returning to Novorossiysk on February 20 aboard the cruiser USS Galveston (CL-19), they found the city flooded with refugees from Kharkov and Rostov. Denikin blamed his subordinates for his military failures, particularly General Pyotr Wrangel, who had advocated a concentration of White forces in the Crimea to make a last stand there in December, a plan that Denikin had rejected. Now in March, it was a disastrous, headlong retreat into the port of Novorossiysk that Denikin had made no provisions for. Instead, while many in the White army and navy had called on Denikin to replace the incompetent Shilling with Wrangel, Denikin had banished Wrangel, a respected and highly competent soldier, to Constantinople.[92] The end of Denikin's army came amidst a brutal winter, and a Typhoid fever epidemic. On March 16, Ekaterinodar, capital of the Kuban province about 80 miles northeast of Novorossiysk was captured by the Reds. On March 26, Red forces reached the vicinity of Novorossiysk, advancing along the railway as the British battleship HMS Emperor of India, the cruiser HMS Calypso and the French cruiser Waldeck-Rousseau fired their naval guns into the hills to support the withdrawal of Denikin's forces. Around noon, fires broke out by the railway yards and waterfront, which soon became uncontrolled infernos, consuming buildings, warehouses, ammunition, oil and rolling stock worth hundreds of thousands of dollars. Tons of weapons, tanks, armored cars and munitions were pushed off the docks into the harbor. As Koehler described it, "Ships lying alongside the docks crowded on human cargo almost to the last inch of space and then, fearing the fire, moved away from the piers into the stream, although they made almost no impression on the multitude seeking to board. packed on the docks and beach, surrounded by raging fire, were thousands who had hoped and expected to be taken away, but who had been left behind for lack of ships to embark them. These were mostly soldiers just arrived from the vanished front, but many women and children were seen among them."[100] Rear Admiral McCully, a humanitarian and a naval officer, recommended to the State Department, that the Russian refugees from the Caucus and Kuban be granted asylum, but was turned down. Although Admiral Bristol was also a humanitarian, and ultimately played a major role in the resettlement of displaced persons from the region, he did not then want to be saddled with thousands of refugees and ordered McCully to bring no more than 250 down the Bosporus Strait in his ships. About 200 women and children were transported on Galveston and the destroyer, USS Smith Thompson (DD-212) to Proti Island in the Sea of Marmara, with another thousand transported on American ships to the Crimea.[101][102] On the morning of March 27, Galveston stood out from Novorossiysk, with 3-inch shells from Red shore batteries falling perilously close, as the beleaguered city fell to the Reds. Koehler wrote, "Several small boat trips were made from the Galveston in a last effort to rescue a few more women and children, but it was impossible to get any considerable number of them through the throng."[103] Besides troops and refugees pouring into the Crimea, another 50,000 refugees were transported to the Bosporus on Russian ships.[104] Koehler described the plight of those who could not flee, but instead sought to negotiate with the Bolsheviks for surrender, "The Reds promised immunity to all except malefactors, on the condition the troops would march against the Poles; but immediately on the surrender being accomplished, the Reds began the usual slaughter of officers and stripped the soldiers of their clothes. The Cossacks again took to arms, about 10,000 taking to the hills and about 2,000 escaping across the Georgian border. Unable to take them along, about 700 children were drowned at the beach by their mothers, who then took to the hills with the men."[105]

-

American Red Cross Officer, Lt. L.M. Foster with mobile, surplus army field kitchen at Novorossiysk Russia, three days before the City fell to the Reds, March 1920

-

Russian refugees on Red Cross Relief Ship, Sangamon, Novorossiysk, March 1920

-

Refugee children that were separated from their parents during the Novorossiysk exodus with Lt. L.M. Foster, aboard the relief ship, Sangamon, March 1920

The debacle at Novorossiysk completely discredited Denikin, who fled the Crimea on March 21 and sailed to England. One of his last acts was to begrudgingly appoint General (Baron) Pyotr Wrangel as commander in chief of the White resistance. On April 4, Denikin issued a proclamation to the Don, Terek and Kuban cossack representatives dissolving the democratic government that had been formed on February 4, but making no provision for representative institutions.[106] Wrangel, known as the "Black Baron" by the Reds, immediately locked down the Crimea as the last enclave of the White movement, ruthlessly restoring discipline by executing all looters, agitators, speculators and commissars, in one instance parading 370 men in front of him and then having them all shot. The remaining men were offered the alternative of joining the White Army.[107] On April 10, Wrangel sailed with an expedition to Perekop in the Sea of Azov and after six days of heavy fighting had made a slight advance to secure a path for egress of the Crimean forces to the north, a tactical and symbolic advance that revived morale among the White troops and the confidence of the people that supported the resistance.[108] With the reorganization of the White forces, on June 1, 1920, the "Black Baron" had an operational army of 40,000, consisting of First Corps under General Alexander Kutepov at Perekop with 7,000 Volunteer Army infantry, 46 guns, 12 tanks, 21 aeroplanes and 500 cavalry; Second Corps under General Yakov Slashchov, organized for a combined naval and military expedition to a port on the Sea of Azov, with 10,000 men in all, 58 guns, 3 aeroplanes, 5 armored motorcars and 400 cavalry; Third Corps under General A. Pisarev at the Sivash Isthmus with 11,000 men total, 19 guns, 9 aeroplanes, 3 armored trains, and 1,960 cavalry; and Fourth Corps, composed of dismounted Kuban cossacks, 14 guns, and about 16,000 men in reserve near Sivash.[109] Wrangel also improved the naval assets of the White forces, with a Black Sea and separate Azov Sea flotilla. Receiving coal shipments from Constantinople in April and May to enable the ships to steam, the Black Sea ships numbered a battleship, three cruisers, ten destroyers and eight gunboats, and in the Azov Sea the Whites had fifteen shallow-draft boats.

Morale was also greatly improved, and while for the first time since the spring of 1918, the Cossacks did not figure as the prominent element of the White army, with a corresponding decrease in cavalry superiority, the army was now made up of men who were determined to fight the enemy.[110] As Koehler wrote in his report, "The Cossacks are fighting to get back to their stanitzi in the Don and the Kuban- nor do they see much beyond that. They do not loot now, but resent being deprived of (as they look at it) a well-earned privilege... Russia means nothing to them... They... fight any... power or regime or idea that interferes with their old privileges."[111]

Melitopol, June 1920

[edit]