Gurjara-Pratihara dynasty

A request that this article title be changed to Pratihara dynasty is under discussion. Please do not move this article until the discussion is closed. |

Gurjara Pratihara dynasty | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 730 CE–1036 CE | |||||||||||||||||||

Gurjara-Pratihara coinage of Mihira Bhoja, King of Kanauj. Obv: Boar, incarnation of Vishnu, and solar symbol. Rev: Traces of Sasanian type. Legend: Srímad Ādi Varāha "The fortunate primaeval boar".[1][2][3]

| |||||||||||||||||||

Extent of the Pratihara Empire at its peak (c. 800—950 CE) and neighbouring polities.[4] | |||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | |||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Sanskrit, Prakrit | ||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Hinduism | ||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||||||||

• c. 730 – c. 760 | Nagabhata I (first) | ||||||||||||||||||

• c. 1024 – c. 1036 | Yasahpala (last) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Late Classical India | ||||||||||||||||||

• Established | c. 730 CE | ||||||||||||||||||

| 1008 CE | |||||||||||||||||||

• Disestablished | 1036 CE | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | India Bangladesh | ||||||||||||||||||

The Pratihara dynasty, also called the Gurjara-Pratiharas, the Pratiharas of Kannauj and the Imperial Pratiharas, was a prominent medieval Indian dynasty. It initially ruled the Gurjaradesa till 816 and from then onwards, the Kingdom of Kannauj until 1036 when the kingdom collapsed due the Ghaznavid invasions.

The Gurjara-Pratiharas were instrumental in containing Arab armies moving east of the Indus River.[5] Nagabhata I defeated the Arab army under Junaid and Tamin in the Caliphate campaigns in India. Under Nagabhata II, the Gurjara-Pratiharas became the most powerful dynasty in northern India. He was succeeded by his son Ramabhadra, who ruled briefly before being succeeded by his son, Mihira Bhoja. Under Bhoja and his successor Mahendrapala I, the Gurjara-Pratihara dynasty reached its peak of prosperity and power. By the time of Mahendrapala, the extent of its territory rivalled that of the Gupta Empire stretching from the border of Sindh in the west to Bengal in the east and from the Himalayas in the north to areas past the Narmada in the south.[6][7] The expansion triggered a tripartite power struggle with the Rashtrakuta and Pala empires for control of the Indian subcontinent. During this period, Imperial Pratihara took the title of Maharajadhiraja of Āryāvarta (Great King of Kings of Aryan Lands).

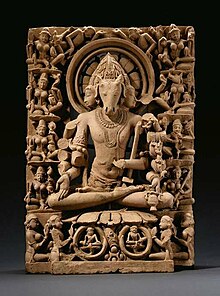

Gurjara-Pratihara are known for their sculptures, carved panels and open pavilion style temples. The greatest development of their style of temple building was at Khajuraho, now a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[8]

The power of the Gurjara-Pratihara dynasty was weakened by dynastic strife. It was further diminished as a result of a great raid led by the Rashtrakuta ruler Indra III who, in about 916, sacked Kannauj. Under a succession of rather obscure rulers, the dynasty never regained its former influence. Their feudatories became more and more powerful, one by one throwing off their allegiance until, by the end of the tenth century, the dynasty controlled little more than the Gangetic Doab. Their last important king, Rajyapala, was driven from Kannauj by Mahmud of Ghazni in 1018.[7]

Etymology and origin

The origin of the dynasty and the meaning of the term "Gurjara" in its name is a topic of debate among historians. The rulers of this dynasty used the self-designation "Pratihara" for their clan, and never referred to themselves as Gurjaras.[9] They claimed descent from the legendary hero Lakshmana, who is said to have acted as a pratihara ("door-keeper") for his brother Rama.[10][11] [12]

Multiple inscriptions of their neighbouring dynasties describe the Pratiharas as "Gurjara".[13] The term "Gurjara-Pratihara" occurs only in the Rajor inscription of a feudatory ruler named Mathanadeva, who describes himself as a "Gurjara-Pratihara". According to one school of thought, Gurjara was the name of the territory (see Gurjara-desha) originally ruled by the Pratiharas; gradually, the term came to denote the people of this territory. An opposing theory is that Gurjara was the name of the tribe to which the dynasty belonged, and Pratihara was a clan of this tribe.[14]

Among those who believe that the term Gurjara was originally a tribal designation, there are disagreements over whether they were native Indians or foreigners.[15] The proponents of the foreign origin theory point out that the Gurjara-Pratiharas suddenly emerged as a political power in north India around sixth century CE, shortly after the Hunas invasion of that region.[16] According to them Gujara-Pratihara were "likely" formed from a fusion of the Alchon Huns ("White Huns") and native Indian elements, and can probably be considered as a Hunnic state, although its precise origins remain unclear.[17][18] Critics of the foreign origin theory argue that there is no conclusive evidence of their foreign origin: they were well-assimilated in the Indian culture. Moreover, if they invaded India through the north-west, it is inexplicable why would they choose to settle in the semi-arid area of present-day Rajasthan, rather than the fertile Indo-Gangetic Plain.[19]

According to the Agnivansha legend given in the later manuscripts of Prithviraj Raso, the Pratiharas, Parmar, Chauhan and Chalukya dynasties originated from a sacrificial fire-pit (agnikunda) at Mount Abu. Some colonial-era historians interpreted this myth to suggest a foreign origin for these dynasties. According to this theory, the foreigners were admitted in the Hindu caste system after performing a fire ritual.[20] However, this legend is not found in the earliest available copies of Prithviraj Raso. It is based on a Paramara legend; the 16th century Rajput bards claim heroic descent of clans in order to foster Rajput unity against the Mughals.[21]

History

The original centre of Pratihara power is a matter of controversy. R. C. Majumdar, on the basis of a verse in the Harivamsha-Purana, 783 CE, the interpretation of which he conceded was not free from difficulty, held that Vatsaraja ruled at Ujjain.[22] Dasharatha Sharma, interpreting it differently located the original capital in the Bhinmala Jalor area.[23] M. W. Meister[24] and Shanta Rani Sharma[25] concur with his conclusion in view of the fact that the writer of the Jaina narrative Kuvalayamala states that it was composed at Jalor in the time of Vatsaraja in 778 CE, which is five years before the composition of Harivamsha-Purana.

Early rulers

Nagabhata I (739–760), was originally perhaps a feudatory of the Chavdas of Bhillamala. He gained prominence after the downfall of the Chavda kingdom in the course of resisting the invading forces led by the Arabs who controlled Sindh. Nagabhata Pratihara I (730–756) later extended his control east and south from Mandor, conquering Malwa as far as Gwalior and the port of Bharuch in Gujarat. He established his capital at Avanti in Malwa, and checked the expansion of the Arabs, who had established themselves in Sind. In this battle (738 CE), Nagabhata led a confederacy of Pratiharas to defeat the Muslim Arabs who had till then been pressing on victorious through West Asia and Iran. An inscription by Mihira Bhoja ascribes Nagabhata with having appeared like Vishnu "in response to the prayers of the oppressed people to crush the large armies of the powerful Mleccha ruler, the destroyer of virtue".[26] Nagabhata I was followed by two weak successors, his nephews Devraj and Kakkuka, who were in turn succeeded by Vatsraja (775–805).

Resistance to the Caliphate

In the Gwalior inscription, it is recorded that Gurjara-Pratihara emperor Nagabhata "crushed the large army of the powerful Mlechcha king." This large army consisted of cavalry, infantry, siege artillery, and probably a force of camels. Since Tamin was a new governor he had a force of Syrian cavalry from Damascus, local Arab contingents, converted Hindus of Sindh, and foreign mercenaries like the Turkics. All together the invading army may have had anywhere between 10 and 15,000 cavalry, 5000 infantry, and 2000 camels.[citation needed]

The Arab chronicler Sulaiman describes the army of the Pratiharas as it stood in 851 CE, "The ruler of Gurjara maintains numerous forces and no other Indian prince has so fine a cavalry. He is unfriendly to the Arabs, still he acknowledges that the king of the Arabs is the greatest of rulers. Among the princes of India there is no greater foe of the Islamic faith than he. He has got riches, and his camels and horses are numerous."[27]

Conquest of Kannauj and further expansion

After bringing much of Rajasthan under his control, Vatsaraja embarked to become "master of all the land lying between the two seas." Contemporary Jijasena's Harivamsha Purana describes him as "master of western quarter".[28]

According to the Radhanpur Plate and Prithviraja Vijaya, Vatsaraja led an expedition against the Palas under Dharmapala of Bengal As such, the Palas came into conflict from time to time with the Imperial Pratiharas. According to the above inscription Dharmapala, was deprived of his two white Royal Umbrellas, and fled, followed by the Pratihara forces under general Durlabharaja Chauhan of Shakambhari. The Prithviraja Vijaya mentions Durlabhraj I as having "washed his sword at the confluence of the river Ganga and the ocean, and savouring the land of the Gaudas". The Baroda Inscription (AD 812) states Nagabhata defeated the Dharmapala. Through vigorous campaigning, Vatsraj had extended his dominions to include a large part of northern India, from the Thar Desert in the west up to the frontiers of Bengal in the east.[28]

The metropolis of Kannauj had suffered a power vacuum following the death of Harsha without an heir, which resulted in the disintegration of the Empire of Harsha. This space was eventually filled by Yashovarman around a century later but his position was dependent upon an alliance with Lalitaditya Muktapida. When Muktapida undermined Yashovarman, a tri-partite struggle for control of the city developed, involving the Pratiharas, whose territory was at that time to the west and north, the Palas of Bengal in the east and the Rashtrakutas, whose base lay at the south in the Deccan.[29][30] Vatsaraja successfully challenged and defeated the Pala ruler Dharmapala and Dantidurga, the Rashtrakuta king, for control of Kannauj.

Around 786, the Rashtrakuta ruler Dhruva (c. 780–793) crossed the Narmada River into Malwa, and from there tried to capture Kannauj. Vatsraja was defeated by the Dhruva Dharavarsha of the Rashtrakuta dynasty around 800. Vatsaraja was succeeded by Nagabhata II (805–833), who was initially defeated by the Rashtrakuta ruler Govinda III (793–814), but later recovered Malwa from the Rashtrakutas, conquered Kannauj and the Indo-Gangetic Plain as far as Bihar from the Palas, and again checked the Muslims in the west. He rebuilt the great Shiva temple at Somnath in Gujarat, which had been demolished in an Arab raid from Sindh. Kannauj became the center of the Gurjara-Pratihara state, which covered much of northern India during the peak of their power, c. 836–910.[citation needed]

Mihira Bhoja

Mihira Bhoja first consolidated his territories by crushing the rebellious feudatories in Rajasthan, before turning his attention against the old enemies, the Palas and Rastrakutas.[35] The Palas of Bengal, ruled by King Devapala (c. 810–850), were reputed to have:

Eradicated the race of the Utkalas, humbled the pride of the Hunas and scattered the conceit of the Dravidas and Pratiharas.

When Mihira Bhoja started his career reverses and defeats suffered by his father Ramabhadra had considerably lowered the prestige of the Royal Pratihara family. He invaded the Pala Empire of Bengal, but was defeated by Devapala

He then launched a campaign to conquer the territories to the south of his empire and was successful, Malwa, Deccan and Gujarat were conquered. In Gujarat he Stepped into a war of succession for the throne of Gujarat between Dhruva II of the Gujarat Rashtrakuta dynasty and his younger brother, Bhoja led a cavalry raid into Gujarat against the Dhruva while supporting his Dhruva's younger brother. Although the raid was repulsed by Dhruva II. Bhoja I was able to retain dominion over parts of Gujarat and Malwa.[35]

The Pratiharas were defeated in a large battle in Ujjain by the Rastrakutas of Gujarat. However, retribution followed on the part of the Pratiharas, by the end of his reign, Bhoja had successfully destroyed the Gujarat Rashtrakuta dynasty.[36]: 20–21

Bhoja's feudatory, the Guhilas chief named Harsha of Chatsu, is described as :

"defeating the northern rulers with the help of the mighty elephant force", and "loyally presenting to Bhoja the special 'Shrivamsha' breed of horses, which could easily cross seas of sand."

He gradually rebuilt the empire by conquest of territories in Rajasthan, Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh.[37] Besides being a conqueror, Bhoja was a great diplomat.[37] The Kingdoms which were conquered and acknowledged his Suzerainty includes Travani, Valla, Mada, Arya, Gujaratra, Lata Parvarta

and Chandelas of Bundelkhand. Bhoja's Daulatpura-Dausa Inscription(AD 843), confirms his rule in Dausa region. Another inscription states that,"Bhoja's territories extended to the east of the Sutlej river."

Kalhana's Rajatarangini states that the territories of Bhoja extended to Kashmir in the north, and bhoja had conquered Punjab by defeating ruling 'Thakkiyaka' dynasty .[35][38]

After Devapala's death, Bhoja defeated the Pala King Narayanapala and expanded his boundaries eastward into Pala-held territories near Gorakhpur.

Hudud-ul-Alam a tenth century Persian geographic text states that most of the kings of India acknowledged the supremacy of the powerful 'Rai of Qinnauj', (kannauj was the capital of Imperial Pratiharas) whose mighty army had 150,000 strong cavalry and 800 war elephants.[35]

His son Mahenderpal I (890–910), expanded further eastwards in Magadha, Bengal and Assam.[39]

Decline

Bhoja II (910–912) was overthrown by Mahipala I (912–944). Several feudatories of the empire took advantage of the temporary weakness of the Gurjara-Pratiharas to declare their independence, notably the Paramaras of Malwa, the Chandelas of Bundelkhand, the Kalachuris of Mahakoshal, the Tomaras of Haryana, and the Chahamanas of Shakambhari.[42] The south Indian Emperor Indra III (c. 914–928) of the Rashtrakuta dynasty briefly captured Kannauj in 916, and although the Pratiharas regained the city, their position continued to weaken in the tenth century, partly as a result of the drain of simultaneously fighting off Turkic attacks from the west, the attacks from the Rashtrakuta dynasty from the south and the Pala advances in the east.[42] The Gurjara-Pratiharas lost control of Rajasthan to their feudatories, and the Chandelas captured the strategic fortress of Gwalior in central India around 950.[42] By the end of the tenth century the Gurjara-Pratihara domains had dwindled to a small state centered on Kannauj.[42]

Mahmud of Ghazni captured Kannauj in 1018, and the Pratihara ruler Rajapala fled. He was subsequently captured and killed by the Chandela ruler Vidyadhara.[43][44][42] The Chandela ruler then placed Rajapala's son Trilochanpala on the throne as a proxy. Jasapala, the last Gurjara-Pratihara ruler of Kannauj, died in 1036.[42]

The Imperial Pratihara dynasty broke into several small states after the Ghaznavid invasions. These branches fought each other for territory and one of the branches ruled Mandore till the 14th century. This Pratihara branch had marital ties with Rao Chunda of the Rathore clan and gave Mandore in dowry to Chunda. This was specifically done to form an alliance against the Turks of the Tughlaq Empire.[45]

Gurjara-Pratihara art

There are notable examples of architecture from the Gurjara-Pratihara era, including sculptures and carved panels.[46] Their temples, constructed in an open pavilion style. One of the most notable Gurjara-Pratihara style of architecture was Khajuraho, built by their vassals, the Chandelas of Bundelkhand.[8]

Māru-Gurjara architecture

Māru-Gurjara architecture was developed during Gurjara-Pratihara Empire.

- Mahavira Jain temple, Osian temple was constructed in 783 CE,[47] making it the oldest surviving Jain temple in western India.[48]

- Bateshwar Hindu temples, Madhya Pradesh was constructed during the Gurjara-Pratihara Empire between 8th to 11th century.[49]

- Baroli temples complex are eight temples, built by the Gurjara-Pratiharas, is situated within a walled enclosure.

-

One of the four entrances of the Teli ka Mandir. This Hindu temple was built by the Pratihara emperor Mihira Bhoja.[31]

-

Jainism-related cave monuments and statues carved into the rock face inside Siddhachal Caves, Gwalior Fort.

-

Ghateshwara Mahadeva temple at Baroli Temples complex. The complex of eight temples, built by the Gurjara-Pratiharas, is situated within a walled enclosure.

-

Bateshwar Hindu temples in Madhya Pradesh was built by the Gurjara-Pratiharas.

Legacy

Historians of India, since the days of Elphinstone, have wondered at the slow progress of Muslim invaders in India, as compared with their rapid advance in other parts of the world. The Arabs possibly only stationed small invasions independent of the Caliph. Arguments of doubtful validity have often been put forward to explain this unique phenomenon. Currently it is believed that it was the power of the Gurjara-Pratihara army that effectively barred the progress of the Muslims beyond the confines of Sindh, their first conquest for nearly three hundred years. In the light of later events this might be regarded as the "Chief contribution of the Gurjara-Pratiharas to the history of India".[27]

List of rulers

| Serial No. | Ruler | Reign (CE) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Nagabhata I | 730–760 |

| 2 | Kakustha and Devaraja | 760–780 |

| 3 | Vatsaraja | 780–800 |

| 4 | Nagabhata II | 800–833 |

| 5 | Ramabhadra | 833–836 |

| 6 | Mihira Bhoja or Bhoja I | 836–885 |

| 7 | Mahendrapala I | 885–910 |

| 8 | Bhoja II | 910–913 |

| 9 | Mahipala I | 913–944 |

| 10 | Mahendrapala II | 944–948 |

| 11 | Devapala | 948–954 |

| 12 | Vinayakapala | 954–955 |

| 13 | Mahipala II | 955–956 |

| 14 | Vijayapala II | 956–960 |

| 15 | Rajapala | 960–1018 |

| 16 | Trilochanapala | 1018–1027 |

| 17 | Yasahpala | 1024–1036 |

List of feudatories and Branches

| History of India |

|---|

| Timeline |

List of Pratihara feudatories

List of Pratihara Branches

- Gurjara-Pratihara dynasty of Mandavyapura (c. 550 – 750 CE)

- Baddoch Branch (c. 600 – 700 CE)

Known Baddoch rulers are-

- Rajogarh Branch

Badegujar were rulers of Rajogarh

- Parmeshver Manthandev, (885 – 915 CE)

- No records found after Parmeshver Manthandev

See also

- Mihira Bhoja

- Tripartite Struggle

- Gurjara-Pratihara dynasty of Mandavyapura

- History of Rajasthan

- List of battles of Rajasthan

- Umayyad campaigns in India

- List of Rajput dynasties and states

- List of Hindu empires and dynasties

References

- ^ Smith, Vincent Arthur; Edwardes, S. M. (Stephen Meredyth) (1924). The early history of India : from 600 B.C. to the Muhammadan conquest, including the invasion of Alexander the Great. Oxford : Clarendon Press. p. Plate 2.

- ^ Ray, Himanshu Prabha (2019). Negotiating Cultural Identity: Landscapes in Early Medieval South Asian History. Taylor & Francis. p. 164. ISBN 9781000227932.

- ^ Flood, Finbarr B. (20 March 2018). Objects of Translation: Material Culture and Medieval "Hindu-Muslim" Encounter. Princeton University Press. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-691-18074-8.

- ^ Schwartzberg, Joseph E. (1978). A Historical atlas of South Asia. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 146, map XIV.2 (i). ISBN 0226742210.

- ^ Wink, André (2002). Al-Hind: Early Medieval India and the Expansion of Islam, 7th–11th Centuries. Leiden: BRILL. p. 284. ISBN 978-0-391-04173-8.

- ^ Avari 2007, p. 303.

- ^ a b Sircar 1971, p. 146.

- ^ a b Partha Mitter, Indian art, Oxford University Press, 2001 pp.66

- ^ Sanjay Sharma 2006, p. 188.

- ^ Tripathi 1959, p. 223.

- ^ Puri 1957, p. 7.

- ^ Agnihotri, V. K. (2010). Indian History. Vol. 26. p. B8.

Modern historians believed that the name was derived from one of the kings of the line holding the office of Pratihara in the Rashtrakuta court

- ^ Puri 1957, p. 9-13.

- ^ Majumdar 1981, pp. 612–613.

- ^ Puri 1957, p. 1-2.

- ^ Puri 1957, p. 2.

- ^ Kim, Hyun Jin (19 November 2015). The Huns. Routledge. pp. 62–64. ISBN 978-1-317-34091-1.

Although it is not certain, it also seems likely that the formidable Gurjara Pratihara regime (ruled from the seventh-eleventh centuries AD) of northern India,may had a powerful White Hunnic element. The Gurjara Pratiharas who were likely created from a fusion of White Hunnic and native Indian elements, ruled a vast Empire in northern India, and they also halted Arab Muslim expansion in India through Sind for centuries...

- ^ Wink, André (1991). Al-hind: The Making of the Indo-islamic World. BRILL. p. 279. ISBN 978-90-04-09249-5.

- ^ Puri 1957, pp. 4–6.

- ^ Yadava 1982, p. 35.

- ^ Singh 1964, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Majumdar, R.C. (1955). The Age of Imperial Kanauj (First ed.). Bombay: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan. pp. 21–22.

- ^ Sharma, Dasharatha (1966). Rajasthan through the Ages. Bikaner: Rajasthan State Archives. pp. 124–30.

- ^ Meister, M.W (1991). Encyclopaedia of Indian Temple Architecture, Vol. 2, pt.2, North India: Period of Early Maturity, c. AD 700–900 (first ed.). Delhi: American Institute of Indian Studies. p. 153. ISBN 0195629213.

- ^ Sharma, Shanta Rani (2017). Origin and Rise of the Imperial Pratihāras of Rajasthan: Transitions, Trajectories and Historical Chang (First ed.). Jaipur: University of Rajasthan. pp. 77–78. ISBN 978-93-85593-18-5.

- ^ A New History of Rajasthan, Rima Hooja pg – 270–274 University of Rajasthan

- ^ a b Chaurasia, Radhey Shyam (2002). History of Ancient India: Earliest Times to 1000 A. D. Atlantic Publishers & Distributors. p. 207. ISBN 978-81-269-0027-5.

- ^ a b Hooja, Rima (2006). A History of Rajasthan. Rajasthan: Rupa & Company. pp. 274–278. ISBN 8129108909.

- ^ Chopra, Pran Nath (2003). A Comprehensive History of Ancient India. Sterling Publishers. pp. 194–195. ISBN 978-81-207-2503-4.

- ^ Kulke, Hermann; Rothermund, Dietmar (2004) [1986]. A History of India (4th ed.). Routledge. p. 114. ISBN 978-0-415-32920-0.

- ^ a b K. D. Bajpai (2006). History of Gopāchala. Bharatiya Jnanpith. p. 31. ISBN 978-81-263-1155-2.

- ^ Jain, Kailash Chand (31 December 1972). Malwa Through The Ages. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. pp. 429–430. ISBN 978-81-208-0824-9.

- ^ Rajan, K. V. Soundara (1984). Early Kalinga Art and Architecture. Sundeep. p. 103.

When we have to compare a khākhärä temple of Kalinga with anything outside its borders, the most logical analogue coming to our mind will be that of Teli ka Mandir at Gwalior of the time of Pratihara Mihira Bhoja.

- ^ Sharma, Dr Shiv (2008). India – A Travel Guide. Diamond Pocket Books (P) Ltd. p. 531. ISBN 978-81-284-0067-4.

- ^ a b c d e Hooja, Rima (2006). A History of Rajasthan. Rajasthan: Rupa & Company. pp. 277–280. ISBN 8129108909.

- ^ Sen, S.N., 2013, A Textbook of Medieval Indian History, Delhi: Primus Books, ISBN 9789380607344

- ^ a b Radhey Shyam Chaurasia (2002). History of Ancient India: Earliest Times to 1000 A. D. Atlantic Publishers & Distributors. p. 207. ISBN 978-81-269-0027-5.

He was undoubtedly one of the outstanding political figures of India in ninth century and ranks with Dhruva and Dharmapala as a great general and empire builder.

- ^ Dasharatha Sharma, Rajasthan Through the Ages "a comprehensive and authentic history of Rajasthan" Bikaner, Rajasthan State Archives 1966, pp.144–54

- ^ Indian History. Allied Publishers. 1988. p. 9. ISBN 978-81-8424-568-4.

- ^ Chandra, Satish (2004). Medieval India: From Sultanat to the Mughals-Delhi Sultanat (1206–1526) – Part One. Har-Anand Publications. pp. 19–20. ISBN 978-81-241-1064-5.

- ^ Schwartzberg, Joseph E. (1978). A Historical atlas of South Asia. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 32, 146. ISBN 0226742210.

- ^ a b c d e f Chandra, Satish (2004). Medieval India: From Sultanat to the Mughals-Delhi Sultanat (1206–1526) – Part One. Har-Anand Publications. pp. 19–20. ISBN 978-81-241-1064-5.

- ^ Dikshit, R. K. (1976). The Candellas of Jejākabhukti. Abhinav. p. 72. ISBN 9788170170464.

- ^ Mitra, Sisirkumar (1977). The Early Rulers of Khajurāho. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 72–73. ISBN 9788120819979.

- ^ Belli, Melia (2005). Royal Umbrellas of Stone: Memory, Politics, and Public Identity in Rajput funerary arts. Brill. p. 142. ISBN 9789004300569.

- ^ Kala, Jayantika (1988). Epic scenes in Indian plastic art. Abhinav Publications. p. 5. ISBN 978-81-7017-228-4.

- ^ Kalia 1982, p. 2.

- ^ Cort 1998, p. 112.

- ^ "ASI to resume restoration of Bateshwar temple complex in Chambal". Hindustan Times. 21 May 2018.

Bibliography

- Avari, Burjor (2007). India: The Ancient Past. A History of the Indian-Subcontinent from 7000 BC to AD 1200. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-203-08850-0.

- Sircar, Dineschandra (1971). Studies in the Geography of Ancient and Medieval India. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 9788120806900.

- Ganguly, D. C. (1935), Narendra Nath Law (ed.), "Origin of the Pratihara Dynasty", The Indian Historical Quarterly, XI, Caxton: 167–168

- Majumdar, R. C. (1981), "The Gurjara-Pratiharas", in R. S. Sharma and K. K. Dasgupta (ed.), A Comprehensive history of India: A.D. 985–1206, vol. 3 (Part 1), Indian History Congress / People's Publishing House, ISBN 978-81-7007-121-1

- Majumdar, R.C. (1955). The Age of Imperial Kanauj (First ed.). Bombay: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan.

- Mishra, V. B. (1954), "Who were the Gurjara-Pratīhāras?", Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, 35 (¼): 42–53, JSTOR 41784918

- Meister, M.W (1991). Encyclopaedia of Indian Temple Architecture, Vol. 2, pt.2, North India: Period of Early Maturity, c. AD 700–900 (first ed.). Delhi: American Institute of Indian Studies. p. 153. ISBN 0195629213

- Puri, Baij Nath (1957), The history of the Gurjara-Pratihāras, Munshiram Manoharlal

- Puri, Baij Nath (1986) [first published 1957], The History of the Gurjara-Pratiharas, Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal

- Sharma, Dasharatha (1966). Rajasthan through the Ages. Bikaner: Rajasthan State Archives

- Sharma, Sanjay (2006), "Negotiating Identity and Status Legitimation and Patronage under the Gurjara-Pratīhāras of Kanauj", Studies in History, 22 (22): 181–220, doi:10.1177/025764300602200202, S2CID 144128358

- Sharma, Shanta Rani (2012), "Exploding the Myth of the Gūjara Identity of the Imperial Pratihāras", Indian Historical Review, 39 (1): 1–10, doi:10.1177/0376983612449525, S2CID 145175448

- Singh, R. B. (1964), History of the Chāhamānas, N. Kishore

- Sharma, Shanta Rani (2017). Origin and Rise of the Imperial Pratihāras of Rajasthan: Transitions, Trajectories and Historical Change (First ed.). Jaipur: University of Rajasthan. p. 77–78. ISBN 978-93-85593-18-5.

- Tripathi, Rama Shankar (1959). History of Kanauj: To the Moslem Conquest. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0478-4.

- Yadava, Ganga Prasad (1982), Dhanapāla and His Times: A Socio-cultural Study Based Upon His Works, Concept

- Kalia, Asha (1982), Art of Osian Temples: Socio-economic and Religious Life in India, 8th–12th Centuries A.D., Abhinav Publications, ISBN 9780391025585

- Cort, John E. (1998), Open Boundaries: Jain Communities and Cultures in Indian History, SUNY Press, ISBN 9780791437865

- Pratihara Empire

- States and territories established in the 8th century

- States and territories disestablished in 1036

- History of Rajasthan

- History of Gujarat

- Medieval empires and kingdoms of India

- History of Malwa

- Agnivansha

- 8th-century establishments in India

- 1036 disestablishments in Asia

- 11th-century disestablishments in India

- 8th-century establishments in Nepal

![Gurjara-Pratihara coinage of Mihira Bhoja, King of Kanauj. Obv: Boar, incarnation of Vishnu, and solar symbol. Rev: Traces of Sasanian type. Legend: Srímad Ādi Varāha "The fortunate primaeval boar".[1][2][3] of Gurjara Pratihara](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/7d/Pratihara_bhoja.JPG/250px-Pratihara_bhoja.JPG)

![One of the four entrances of the Teli ka Mandir. This Hindu temple was built by the Pratihara emperor Mihira Bhoja.[31]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/64/Teli_ka_Mandir_%2815702266503%29.jpg/150px-Teli_ka_Mandir_%2815702266503%29.jpg)