Enthronement of the Japanese emperor

This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2017) |

| Enthronement of the Japanese emperor 即位の礼 | |

|---|---|

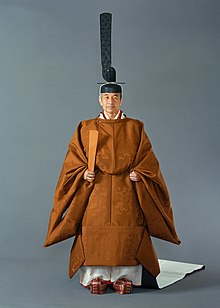

Enthronement of Emperor Naruhito in Tokyo Imperial Palace in 2019 | |

| Location(s) | Tokyo Imperial Palace, Matsu-no-Ma Hall |

| Country | |

| Inaugurated | Empress Suiko (First) Emperor Kanmu (Modern version) |

| Previous event | 22 October 2019 Naruhito |

| Participants |

|

| Website | The Imperial Household Agency Cabinet Public Relations Office, Cabinet Secretariat |

Enthronement (即位の礼, Sokui no rei) is an ancient ceremony that marks the accession of a new emperor to Japan's Chrysanthemum Throne, the world's oldest continuous hereditary monarchy. Various ancient imperial regalia (three sacred treasures) are given to the new sovereign during the course of the rite. It is the most important out of the Japanese Imperial Rituals.

Enthronement ceremonies

[edit]The enthronement ceremony consist of five sub-ceremonies, which are conducted as constitutional functions (国事行為) based on Article 3 of the Constitution of Japan as follows:[1]

Presentation of the Three Sacred Treasures

[edit]

The first is the simplest, Kenji-tō-Shōkei-no-gi (剣璽等承継の儀), it takes place immediately after the death or abdication of the preceding sovereign. The successor is formally presented with boxes containing two of the three items that compose the Imperial Regalia of Japan: (1) a replica sword representing the sword Kusanagi-no-Tsurugi (lit. "Grasscutter Sword") (草薙劍), though the original is allegedly enshrined at Atsuta Shrine in Nagoya; and (2) the Yasakani no magatama (八尺瓊曲玉), a necklace of comma-shaped stone beads. The third and most important of the items of the regalia is the mirror Yata no Kagami (八咫鏡), which is enshrined in the Ise Grand Shrine as the go-shintai (御神体), or the embodiment of the Sun goddess herself. It is permanently housed in the shrine, and is not presented to the emperor for the enthronement ceremony. Imperial messengers and priests are sent to this shrine, as well as to the tomb-shrines of the four emperors whose reigns immediately preceded his, to inform them of the new emperor's accession.

The three items of the imperial regalia were originally said to have been given by the Sun goddess, Amaterasu, to her grandson when he first descended to earth and became the founder of the imperial dynasty. Unlike other monarchies, Japan has no crown in its regalia. In the 2019 enthronement ceremony, the treasures were presented to the new emperor in the morning of his ascension date. The visits to the Ise Grand Shrine by Imperial messengers and priests, as well as to the tombs of the previous four emperors, continued on as in past enthronements.

The first audience after the enthronement

[edit]The second is called Sokui-go-Choken-no-gi (即位後朝見の儀). The new emperor will meet the three chiefs of the tripartite political system as the representatives of citizens for the first time.

Proclaiming enthronement at the main palace

[edit]

The third part of the ceremony, called Sokuirei-Seiden-no-gi (即位礼正殿の儀), is the ritual to proclaim and congratulate the enthronement. It is the core part; the last such ceremony was held on October 22, 2019, for Naruhito.

This ancient rite was traditionally held in Kyoto, the former capital of Japan; beginning in 1990, it is done in Tokyo. The 1990 enthronement of Akihito was the first to be covered on television, and have Imperial Guards in political traditional uniforms. It was done indoors, with the elevated stand placed inside the Imperial Palace complex. Only part of the ritual is public, and the regalia itself is generally seen only by the emperor and a few Shinto priests. First came a three-hour ceremony in which the new emperor ritually informed his ancestors that the enthronement is about to take place. This was followed by the enthronement itself, which takes place per tradition in an enclosure called the Takamikura, containing a great square pedestal upholding three octagonal pedestals topped by a simple chair. This was surrounded by an octagonal pavilion with curtains, surmounted by a great golden Phoenix.[2] At the same time, the empress, in full dress regalia, moved to a smaller adjacent throne beside her husband's. Traditional drums were, at this point of the ceremony, beaten to start the proceedings.[3]

The new emperor proceeded to the chair, where after being seated, the Kusanagi, Yasakani no Magatama, privy seal and state seal were placed on stands next to him. A simple wooden sceptre was presented to the emperor, who faced his prime minister standing in an adjacent courtyard, representing the Japanese people. The emperor offered an address announcing his accession to the throne, calling upon his subjects to single-mindedly assist him in attaining all of his aspirations. His prime minister replied with an address promising fidelity and devotion, followed by a "three cheers of Banzai" from all of those present. The timing of this last event was precisely synchronized, so that Japanese around the world could join in the "Banzai" shout at precisely the moment that it was being offered in Kyoto or in Tokyo.[2]

This moment of the rite ends with the firing of a 21-gun salute by the Japan Self-Defense Forces. After this, both seals and the two regalia items are carried off the imperial pavilion.

Celebration parade

[edit]

The fourth, called Shukuga-Onretsu-no-gi (祝賀御列の儀), is the motorcade procession. The emperor and empress, now back to wearing formal wear, are then both driven through midst Tokyo toward Akasaka Estate by the state limousine (御料車) to acknowledge the cheers of the ordinary citizens on the major streets of the capital who have assembled there. As head of state, he also receives the first salutes on that segment by a guard of honour of the Japan Self-Defense Force and the Imperial Guard Headquarters of the National Police Agency (皇宮警察本部).[4]

In the case of Naruhito, the parade was postponed to November 10, 2019, with consideration about the enormous damage of Reiwa 1 East Japan Typhoon.[5] As the state limousine, a specially coach worked Toyota Century Royal was prepared.[6] In this ceremony, the Imperial Household Agency and constables of the Imperial Guard Headquarters provided guards of honor and security while the Tokyo Metropolitan Police Department's Police band and Japan Ground Self-Defense Force Music Corps played suitable music.[7]

Court banquet

[edit]The fifth is the official banquet, called Kyouen-no-gi (饗宴の儀), which is the occasion to announce and celebrate the enthronement, and to receive the felicitations of the guests to be held within Tokyo Imperial Palace.[5]

Another banquet

[edit]A banquet is hosted by the Prime Minister and their spouse in Tokyo to thank the foreign heads of State and other dignitaries for visiting Japan, and to foster a greater understanding of Japan by presenting displays of traditional Japanese culture.[5][8] This banquet is an event out of the scope of constitutional functions (国事行為).

History of the enthronement ceremony

[edit]

As far as the records in the Kiki are concerned, the coronation ceremony was held on the first day of the year, but it is believed that when the calendar system was imported from the Sui dynasty during the reign of Empress Suiko, the accession to the throne on the first day of the year was adopted, following the example of the continental emperors.[9]

Prior to this, the coronation ceremony was integrated with the Daijō-sai, in which the new emperor appeared before his subjects after receiving the spiritual authority of Amaterasu at a festival the day after the Daijō-sai was held on the winter solstice (around November in the Lunisolar calendar). At this point, the emperor's succession to the throne was announced to the world through the presentation of the Imperial Regalia of Japan[10]

Later, the accession ceremony was moved up to New Year's Day and preceded the Daijō-sai. Although the details of the ceremony are not clear even in the Chronicles, the Divine Instruments were first given and received, and the ceremony of ascending to the "platform" was held on the same day or later.[11]

The first time the rituals were recorded in detail was on New Year's Day 1, the fourth year of Vermilion Bird (February 14, 690). It is the coronation ceremony of Empress Jitō.[a] At this time, the ceremony is as follows[12]

- Isonokami Maro establishes the Big Shield.

- Nakatomi Oshima, Count of Shingi recites the Tenjin Jyushi.

- Imaizumi Irochi consecrates the sacred Kusanagi no Tsurugi and Yata no Kagami.

- The one hundred lords and ladies of the court assemble and perform an eightfold kashiwate.

At this point, the Tenjin Jyushi had been recited twice, along with the Dai-namesai. In the Yōrō Code (720), it is also stated that

On the day of senso, the sermon of Tenjin is performed and the mirror and sword of the Imbibe's divine regalia are raised

It is clear that the transfer of sacred artifacts took place after the jubilee.[13]

However, at the time of the succession to the throne of Emperor Kanmu in the first year of the reign of 781, the enthronement was followed by the Imperial Rescript at Daikoku-den (大黒殿) which effectively separated the Sensō from the enthronement. In the 8th year of extension (930), the Sensō and Enthronement were effectively separated.[14] Furthermore, when Emperor Suzaku succeeded to the throne in 930, Sensō and enthronement were explicitly separated.

In the 870s, the Teikan Ritual and the 11th century Eke Yosei, the accession ceremony was clearly defined as follows.

- The Emperor faces south with a ladle in his high seat.

- The Emperor faces the south on his high throne, holding a ladle.

- Kashiwate, dancing, and congratulating the Emperor and his hundred officials, and three cheers given by the military officials.

Here, the Yōrō Code's provisions for the transfer of the Sword and Seal and the Tenjin jubilee were removed, and the ceremony took on a more continental style, with the Son of Heaven facing south and wearing ceremonial dress.[15]

However, by the middle of the Heian period, this form had already broken down, and the pseudo-attendants in the palace (in the early Heian period, the head of the palace was called the "prince's deputy" because the prince was in charge, and there were a total of six people on either side, consisting of three deputy attendants and a shonagon) were joined by the uchi-ben (equivalent to a superior lord), sotoben (an official who attended the ceremony in general, but only those who were designated to do so), and sotoben (an official who attended the ceremony in general, but only those who were designated to do so). Only nominated persons stand. No one below the rank of a nobleman is allowed to attend. One of the sotoben became the missionary. (From the Middle Ages to the early modern period, it was common for the soto-ben to consist of two each of the daimon, chunagon, and councilors.) In the Middle Ages and early modern times, the sotoben were usually two each from the daionnagon, chunnagon, and counselor. Only a limited number of nobles and officials, such as those in charge of ceremonies, participated in the coronation ceremony, and nobles who did not have that role, even ministers, watched from inside the draperies on either side of the high throne.

The coronation ceremony of Emperor Go-Ichijō on February 7, 1016 (Chōwa 5), was conducted by Dainagon, Fujiwara no Sanesuke, a major figure in the Royal court, wrote in detail in his diary, "Shōyūki", because Sanesuke was able to observe the coronation ceremony as a spectator, not as a participant. In addition, from the late Heian period (after Emperor Horikawa) onward, the regent was in the middle or lower tier of the high palace, and the sekibaku in Sokutai in the east curtain of the north classic aisle, behind the high palace (to the right when viewed from the south). The regent of Emperor Go-Ichijō, Fujiwara no Michinaga, was also in this position, so it is highly likely that early regents were in this position as well.)

As a rule, throughout the Heian period, the venue for ceremonies was the Daigoku-den Hall of the Chodo-in (the eight sects), but due to the burning of the Daigoku-den, Emperor Yōzei used the Fengakuden Hall. Due to illness, Emperor Reizei ascended the throne in the Shichinden Hall of the Interior, and due to the burning of the Daigoku-den, Emperor Go-Sanjō moved to the Emperor Antoku used Hall of Capital in the Inner Palace. Since the Daigoku-den Hall fell into disuse after the Great Fire of Angen in 1176, all emperors from the Kamakura period to Emperor Go-Tsuchimikado of the mid Muromachi period, with the exception of Go-Murakami, Chōkei, and Go-Kameyama of the Southern Court, who were not in Kyoto. After Go-Kashiwabara, the Grand Council of State was not rebuilt, and the Hall of Capital was used, where it remained until Emperor Meiji.

In the Middle Ages and later (the first example is said to be Emperor Go-Sanjō, but it is said to have become customary after Emperor Go-Fukakusa), a Buddhist-style ceremony called the Accession ceremony was also held. This style was continued until the late Edo period.

Although the coronation ceremony is one of the most important Emperor events, the Emperor Go-Kashiwabara of the Sengoku period 1500 (Meiou 9), but was unable to perform the ceremonies, and in 1521 (Daiei Gen), he performed the coronation ceremony in his 22nd year on the throne, based on assistance from the Muromachi shogunate and others. The direct trigger for the ceremony was the shogunate's donation of 20,000 rolls of rice, but in reality, it was not possible to carry out the ceremony with just that money, as the shogunate had donated money several times since the Bunki era, and the Imperial Court had accumulated tools prepared with donations from Honganji and others. Emperor Go-Nara's accession to the throne was postponed for about ten years due to lack of funds, even though there were many items left over from the accession of Emperor Go-Kashiwabara. In the case of Emperor Ogimachi, the imperial treasury was unable to contribute to the cost of the coronation, and the ceremony was held with the assistance of Mōri Motonari. However, despite many difficulties, the ceremony has been performed without fail in every generation, except for Emperor Chūkyō, who only reigned for a short time due to the Jōkyū War.

After the Jokyu Rebellion, when Emperor Shijō ascended to the throne, spectators crowded into the garden, and even after this, there are articles in the court nobles' diaries that suggest that the rituals were hindered by spectators. On the occasion of the accession to the throne of Emperor Go-Kashiwabara, it is said that spectators gathered "like a haze of clouds. In keeping with this tradition, recent research has shown that during the Edo period, the general public was able to watch the accession ceremony at the Kyoto Imperial Palace by purchasing stamps (a kind of ticket).[16] Nomiya Sadaharu, who was not involved in the ceremonies at the time of the accession to the throne of Empress Go-Sakuramachi but only attended the ceremony to see the empress off, was upset that many ordinary court nobles were not allowed to observe the ceremony because of the large number of "samurai slaves" and "miscellaneous people", but that the shogunate's envoys were allowed to see the ceremony unofficially in the Capital Hall.

After the Meiji Restoration, a series of ceremonies related to the senso and accession of the emperor were established by the enactment of the former Imperial Household Law and the Tengoku Order. In addition, there are a number of other rituals and ceremonies that can be performed in Kyoto. The current Imperial Household Law, enacted in 1947 (Shōwa 22), does not specify the location of the ceremonies; the Heisei and Reiwa accession ceremonies were held at the Imperial Palace in Tokyo, with the former name "Shinden no Gi" replaced by "Shoden no Gi".

The ceremony began with an announcement of the due date to Amaterasu, the ancestor deity of the Emperor, and successive emperors, followed by a report to the Three Palaces in the Imperial Palace, and an imperial proclamation to the Ise Grand Shrine. In accordance with the Tengoku Order, the period from Spring to Autumn is designated as the time of accession, and for one year after the Collapse of the previous emperor, the accession ceremony and the Daijō-sai are not held as a period of mourning. This period of mourning is called "Ryoami" in Japanese.

The most important ceremony of the Coronation is the Shoden Ceremony, in which the Emperor wears a Sokutai sash and the Empress wears a Jūnihitoe. The emperor's sash is called Kourouzen-no-ohô, which can only be worn by the emperor. The Throne used in the Shoden ceremony is called "Takamikura" for the emperor and "Michodai" for the empress. It is built on three layers of black-painted sandalwood with an octagonal roof, and decorated with Phoenixs, Mirrors, and other ornaments. It is 5.9 meters high, 6 meters wide, and weighs 8 tons.

Emperor Meiji's enthronement

[edit]

Since the Tempō calendar was in use at the time of the coronation of the 122nd and Meiji Emperor, and the dates differ from the current Gregorian calendar, they are listed in the order of the Tenpō calendar (Gregorian calendar).

On 13 February 1867 (lunar calendar: December 25, Keio 2), following the death of the 121st Emperor Komei, his son, Crown Prince Mutsuhito succeeded to the throne, becoming the 122nd Emperor of Japan. Initially, the accession ceremony was scheduled to take place in November, but it was postponed due to the many difficulties in the country's affairs amidst the rapid changes in the times, including the return of power by Tokugawa Yoshinobu.

In May of the following year, 1868, in order to proclaim the arrival of a new era, the new Meiji government decided to hold a new coronation ceremony appropriate to the changes, and appointed the Tsuwano Domain lord and Department of The Tsuwano Domain and deputy governor of the Department of Divinities, Kamei Korekan, was appointed as the Imperial Accession Ceremony Coordinator. Iwakura Tomomi ordered Kamei to abolish the Tang-style rituals and restore the old style. As a symbol of the new era, the Globe was used in the ceremony to make the emperor's prestige known to the world. Since the Takamiza used for the accession to the throne of Emperor Takamyo had been lost in the fire that destroyed the inner palace in the first year of Ansei (1854), the ledger used for the annual festivities was called Takamiza. Since the costumes and decorations that were considered to be in the Tang style were completely abolished, the ceremonial dress was abolished and the sash, which had been the second formal dress after the ceremonial dress since the Heian period, was used. Flags of honor in the garden were also abolished and replaced by the sakaki flag.

On August 17, Keio 4 (gregorian calendar: 2 October 1868), he announced that his coronation would take place ten days later, on 27 August (12 October 1868), and related ceremonies began on August 21. On the 27th, the next day after the imperial envoy was sent to Emperor Sutoku to read out the decree in front of his spirit on the 26th of the same month, the anniversary of his death, and on the day of the coronation, the decree was read out by the decree envoy, the first person in attendance read out the Norito, and an ancient song was sung. Then they all chanted "Hai" and the ceremony ended.

- Meiji-no-dairei - total cost 43,800 ryō

- Ritual of sending an imperial envoy to Ise Shrine, August 21, 1868 (October 6, 1868)

August 21, 1868 (October 6, 1868) ** Imperial envoy dispatched to Emperor Jimmu's tomb, Emperor Tenchi's tomb, and the tomb of the previous three emperors. August 23 (October 8, the same year) ** Enthronement ceremony

- Enthronement ceremony: August 27 (October 12)

- The Daijō-sai was held in Tokyo on November 17, 1871 (December 28, 1871).

Emperor Taisho's enthronement

[edit]Emperor Taisho was enthroned on 10 November 1915 at the Kyoto Imperial Palace.

Empress Teimei was absent because she was pregnant with their fourth child (Takahito, Prince Mikasa).

Emperor Showa's enthronement

[edit]Emperor Showa was enthroned on 10 November 1928 at the Kyoto Imperial Palace.

Emperor Akihito's enthronement

[edit]Emperor Akihito was enthroned on 12 November 1990 at the Tokyo Imperial Palace.

Emperor Naruhito's enthronement

[edit]Emperor Naruhito was enthroned on 22 October 2019 at the Tokyo Imperial Palace.

The Daijō-sai

[edit]You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Japanese. (December 2021) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

The Daijō-sai (大嘗祭) is a special religious service conducted in November after the enthronement, in which the emperor thanks peace of mind and rich harvest to the Solar deity Amaterasu (天照大神) and surrounding deities, and pray for Japan and its citizens. From Shinto viewpoint, the emperor is believed to be united to deity Amaterasu in a unique way to share in her divinity. In general, the Daijosai is considered as a kind of thanksgiving harvest festival, in the same way as Niiname-sai (新嘗祭) is conducted annually on November 23, a public holiday of Labor Thanksgiving Day. Actually, in the year the Daijō-sai is held, the Niiname-sai (新嘗祭) is not held.[17]

The Emperor and Empress both perform the Daijosai ceremony in November after ascending the throne in a partly televised ceremony and since 2019 it is a livestreamed event. It is only performed once during their reign. Akihito performed it on 22-23 November 1990 and Naruhito on 14-15 November 2019. The Emperor offers gifts such as rice, kelp, millet and abalone to the gods. Then he reads an appeal to the gods and eats the offering and prays. The Emperor and Empress perform the rites separately. It takes about 3 hours. Over 500 people are present including the Prime Minister, government officials, representatives of state and private sector firms, society groups and members of the press. It originates as a Shinto rite from at least the 7th century. It is held as a private event by the Imperial Household, in order that it does not violate the separation of church and state. A special complex with over 30 structures (大嘗宮, daijōkyū) are built for the event. Afterward, they are accessible to the public for a few weeks and then dismantled. In 1990, the ritual cost more than 2.7 billion yen ($24.7 million).[18]

Details

First, two special rice paddies (斎田, saiden) are chosen and purified by elaborate Shinto purification rites. The families of the farmers who are to cultivate the rice in these paddies must be in perfect health. Once the rice is grown and harvested, it is stored in a special Shinto shrine as its go-shintai (御神体), the embodiment of a kami or divine force. Each kernel must be whole and unbroken, and is individually polished before it is boiled. Some sake is also brewed from this rice. The two sets of rice seedlings now blessed each come from the western and eastern prefectures of Japan, and the chosen rice from these is assigned from a designated prefecture each in the west and east of the country, respectively.

Two thatched roof two-room huts (悠紀殿 yukiden, lit. East-region hall) and (主基殿 sukiden, lit. West-region hall) are built within a corresponding special enclosure, using a native Japanese building style that predates and is thus devoid of all Chinese cultural influence. The Yukiden and Sukiden represent the east and west halves of Japan, respectively. Each hall is divided into two rooms, with one room containing a large couch made of tatami mats at its center, in addition to a seat for the emperor and a place to enshrine the kami; the second is used by musicians. All furniture and household items also preserve these earliest, and thus most purely Japanese forms: e.g., all pottery objects are fired but unglazed. These two structures represent the house of the preceding emperor and that of the new emperor. In earlier times, when the head of a household died his house was burned; before the founding of Kyoto, whenever an emperor died his entire capital city was burned as a rite of purification. As in the earlier ceremony, the two houses represent housing styles from western and eastern parts of Japan. Since 1990, the temporary enclosure is located at the eastern grounds of the Imperial Palace complex.

After a ritual bath, the emperor is dressed entirely in the white silk dress of a Shinto priest, but with a special long train. Surrounded by courtiers (some of them carrying torches), the emperor solemnly enters first the enclosure and then each of these huts in turn and performs the same ritual—from 6:30 to 9:30 PM in the first, and in the second from 12:30 to 3:30 AM on the same night. A mat is unrolled before him and then rolled up again as he walks, so that his feet never touch the ground. A special umbrella is held over the sovereign's head, in which the shade hangs from a phoenix carved at the end of the pole and prevents any defilement of his sacred person coming from the air above him. Kneeling on a mat situated to face the Grand Shrine of Ise, as the traditional gagaku court music is played by the court orchestra the emperor makes an offering of the sacred rice, the sake made from this rice, millet, fish and a variety of other foods from both the land and the sea to the kami, the offerings of east and west being made in their corresponding halls. Then he eats some of this sacred rice himself, as an act of divine communion that consummates his singular unity with Amaterasu-ōmikami, thus making him (in Shinto tradition) the intermediary between Amaterasu and the Japanese people. He then prays to the gods in gratitude, and then leaves the huts.[19]

Gallery

[edit]-

Mockup, layout plan for pavilions in the Daijōkyū for the Daijōsai ceremony in November 2019.

-

Kareta, Special Parade of the Ceremonial Horse-Drawn Carriages 2009

See also

[edit]Annotations

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "閣議決定:天皇陛下の御退位及び皇太子殿下の御即位に伴う国の儀式等の挙行に係る基本方針について" [Cabinet decision: Basic Principles for conducting state ceremonies etc. regarding to abdication of His Majesty the Emperor and enthronement of His Imperial Highness] (PDF). Prime Minister's Office of Japan. April 3, 2018. Retrieved February 26, 2021.

- ^ a b "Emperor Enthroned". Time. November 19, 1928. Archived from the original on January 13, 2009. Retrieved October 12, 2008.

- ^ "Japan emperor to announce enthronement in ancient-style ceremony". Mainichi Daily News. October 22, 2019. Archived from the original on October 22, 2019. Retrieved October 22, 2019.

- ^ "祝賀御列の儀" [Celebration parade]. Prime Minister's Office of Japan. December 6, 2019. Retrieved February 24, 2021.

- ^ a b c "Announcement on the Ceremonies of the Accession to the Throne of His Majesty the Emperor". Cabinet Office, Japan. 2019. Retrieved February 25, 2021.

- ^ Christopher Smith (2019). "Custom Toyota Century Convertible Ready To Serve Japan's New Emperor". motor1. Retrieved February 27, 2021.

- ^ "令和の「祝賀御列の儀」フォトドキュメント" [Photodocument of Shukuga-Onretsu-no-gi of Reiwa]. Nippon.com. November 10, 2019. Retrieved March 18, 2021.

- ^ "Japan to invite guests from 195 nations for events marking enthronement of new Emperor". The Japan Times. March 19, 2019. Retrieved February 25, 2021.

- ^ Mayumi 2019, pp. 169–170.

- ^ Mayumi 2019, pp. 170–172, 176.

- ^ Mayumi 2019, pp. 29–30.

- ^ Mayumi 2019, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Mayumi 2019, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Mayumi 2019, pp. 33–34.

- ^ Mayumi 2019, p. 33.

- ^ "天皇即位式、江戸時代は庶民の人気行事 ニュース 列島いにしえ探訪 文化 伝統 関西発 Yomiuri Online(読売新聞)". Archived from the original on November 20, 2006. Retrieved February 10, 2022.

- ^ Tsunetada Mayumi [in Japanese] (2019). 大嘗祭 [Enthronement of the Japanese emperor]. Chikuma Shinsyo. Chikuma Shobō.

- ^ Yukihiro Enomoto. "Japan emperor performs centuries-old succession rite". Nikkei Asian Review. Archived from the original on September 23, 2020. Retrieved September 24, 2020.

- ^ Schoenberger, Karl (November 23, 1990). "Akihito in Final Ritual of Passage". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 2, 2010.

Works cited

[edit]- Mayumi, Tsunetada [in Japanese] (2019). 大嘗祭 [Enthronement of the Japanese emperor]. Chikuma Shinsyo. Chikuma Shobō. ISBN 978-4480099198.

Further reading

[edit]- Saitō Katsuhisa (October 21, 2019). "Pomp and Pageantry: Emperor Naruhito's Enthronement Ceremony". nippon.com.

- Robert S. Ellwood, The Feast of Kingship: Accession Ceremonies in Ancient Japan (Tokyo: Sophia University, 1973).

- D. C. Holtom, Japanese Enthronement Ceremonies: With an Account of the Imperial Regalia (Tokyo: Sophia University, 1972).

- John Breen and Mark Teeuwen, New history of Shinto (Wiley-Blackwell, 2010), pp. 168–198.