The Bells of Basel

The Bells of Basel (French: Les Cloches de Bâle) is a novel by Louis Aragon, the first in the cycle Le Monde Réel (The Real World), first published in 1934. It was a groundbreaking work in the author's oeuvre, confirming his departure from surrealism previously promoted, in favor of realism with a clear ideological message. From then on, the writer regarded his novels not only as literary works but also as Marxist social analyses aimed at encouraging readers to engage in the labor movement.

The first translation of The Bells of Basel into English was made by Haakon Chevalier in 1937.

Circumstances of creation

[edit]According to Roger Garaudy, The Bells of Basel is a pioneering book, a transitional work, in the process of writing which Aragon was developing the language, structure, and style typical of later works.[1] This work was intended to be a complete departure from the author's previous creativity, based on the general outline of Le Monde Réel, on the one hand, and on the other hand, being a kind of experimental novel, the plan of which changed during the writing process.[1] The shape of the work was particularly influenced by the author's wife, Elsa Triolet, who read the emerging fragments of the novel on an ongoing basis and was their first reviewer. According to Garaudy, Triolet's critical comments on the form of the first part of the novel prompted Aragon to change the form of the second and third parts.[2] Zofia Jaremko-Pytowska emphasizes that the thorough change in Aragon's writing style was related to the realistic literary tradition of France, works in which the psychological analysis of the individual was combined with a detailed description of the social background. This type of literature was advocated as the most complete in the circles of Western European left-wing, to which the writer belonged.[3] However, Aragon consciously rejected the postulate of neutrality in narration advocated by French realist writers, deciding to make the novel a reflection of his own Marxist political views.[4] The choice of the work's themes was influenced by the atmosphere of the contemporary era for the creator. Aware of the danger of a new world war breaking out, he decided to present in the novel the years preceding the beginning of the previous one.[5] The concept of the work underwent further, albeit less significant transformations as it was created, remaining in close relation to the author's political commitment.[6]

Aragon dedicated the finished novel to Elsa Triolet.[7]

Plot

[edit]The Bells of Basel consists of four parts: Diana, Catherine, Victor, and Clara.

Diana

[edit]The main character of this part is Diana de Nettencourt, a divorcee, the last descendant of a ruined aristocratic family, a dissolute woman living off the money of successive wealthy lovers. Eventually, for money, she marries a wealthy man named Brunel, who turns out to be a pimp and usurer. When one of his clients, Peter de Sabran, a representative of an old aristocratic family, commits suicide, Diana leaves her husband to avoid losing her reputation as an honest woman. After obtaining a legal separation from her husband, she becomes the mistress of the industrialist Wisner, while her bankrupt husband, on the advice of the same entrepreneur, joins the police as an agent provocateur.

Catherine

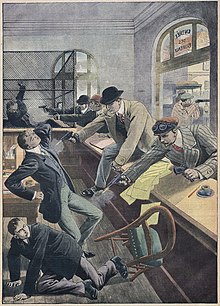

[edit]The main character of this part is a Georgian by origin and the daughter of an industrialist from Baku and a luxury courtesan. She spends her childhood traveling with her mother, observing men courting her. She grows into a beautiful woman but does not want to share her mother's fate in the future. Infatuated with the military man Thiebault, she becomes his mistress but ends the relationship with him – though financially beneficial – when he takes part in suppressing a strike in Cluses. The image of the workers' demonstration prompts her to rebel against her own environment. Catherine starts attending anarchist meetings, where she falls under the influence of the charismatic activist, Libertad. However, gradually, the anarchist worldview also begins to disappoint her. She accidentally witnesses the murder of Libertad by the police, after which she learns that he was an agent provocateur.

Victor

[edit]Convinced of the emptiness of her life, Catherine accidentally finds a mention in the newspaper of the suicide of Paul and Laura Lafargue. This event suggests to her the idea of ending her own life in a similar way. However, at the moment she wants to throw herself into the Seine, she is stopped by a young chauffeur, Victor Deyhanin. Feeling sudden trust in the man, she tells him the story of her life. He decides to introduce the young Georgian woman to the environment of workers and labor activists. In Paris, a major strike of taxi drivers takes place, which Victor helps to organize. Catherine, distrustful of socialist ideals, feels alien among the workers, not understanding the goals of their struggle. She criticizes Victor's views from the standpoint of anarchism, but gradually, under his influence, she breaks with the proclaimed praise of individual terror and attacks. In Paris, at the turn of 1911–1912, a sense of inevitable war grows, and further workers' protests erupt. In the National Assembly vote, the socialists, contrary to earlier announcements, vote to grant war credits to the government. Catherine again hesitates between the elegant society her mother wants to introduce her to and the anarchists. Her political sympathies are detected by the police, and she is arrested and forced to leave France.

Epilogue – Clara

[edit]

In the epilogue, the congress of the Second International in 1912 is depicted in the Basel Minster. Delegates from all sections of the organization are present in the city. Jean Jaurès delivers a great anti-war speech. On the last day of the congress, the voice is taken by Clara Zetkin, a member of the German Social Democratic Party, whom Aragon – unlike other women appearing in the work – presents as a woman of the future, truly worthy of praise.

Characteristics

[edit]Form and message of the novel

[edit]According to Roger Garaudy:

One cannot judge this novel and its composition by classical criteria. It is not built on the basis of action development. It submits to the internal dialectics of the writer's development and his times.[2]

Despite the overall structure as a novel, there are clear differences between its individual parts. Diana was written in a constructionally similar manner to Honoré de Balzac's novella.[8] Such a narrative approach was criticized by Elsa Triolet, who suggested a different, more free-form text to the writer. This suggestion was actually applied in the second and third parts. However, Garaudy believes that the first part, although the least innovative, is the most formally successful component of the novel.[9] Aragon later claimed that it was during the writing of The Bells of Basel that he learned to write novels and admitted that the work contains numerous formal flaws resulting from his lack of experience in this type of writing.[10] He was also harsh in his assessment of all his texts written between 1930 and 1935 when he moved away from surrealism towards realism.[11] In the novel itself, he included another comment in this regard, stating that the "poor construction" of the work reflects a similarly improper social structure, in which the reader should engage in changing:[10]

The world, reader, is poorly constructed, just as poorly constructed as you think my book is. Yes, both must be reworked, with Clara as the protagonist, not with Diana and not with Catherine. If I have encouraged you even a little to do so, you can tear up this little book, what do I care![12]

By dividing the novel into three parts and an epilogue, Aragon indicated that each component of the work is dedicated to a different social layer. The first part depicts the wealthiest circles of France, industrialists, military, and the slowly declining aristocracy. The second part is devoted to the representative of the previously described environment, who wants to break away from it. The third part is dedicated to French workers, while the epilogue, resembling the form of a journalistic report,[13] anticipates a better world that the socialist revolution is supposed to bring.[14] The strict allocation of characters to their social environments – except for Catherine – significantly influences their characterization and the resulting assessment. The characters in The Bells of Basel are generally already formed and do not change throughout the action. The events involving them gradually reveal their hidden traits, contributing to the unmasking of the entire environment. An exemplary case is the character of Brunel, who initially appears as an elegant and well-mannered man but turns out to be capable of murder, a usurer, a police provocateur, and a cynic.[15] The characters of The Bells of Basel are typically one-dimensional. By primarily wanting to present a general picture of each social class, Aragon does not differentiate psychologically between the people constituting them. Consequently, both unambiguously negative representatives of the world of financial elites and workers depicted solely in a positive light (although not activists) become schematic characters. According to Jaremko-Pytowska, the merits of the work in terms of social analysis do not correspond to a thorough psychology of individual characters; the only exception is the continuously metamorphosing Catherine.[16] Unambiguous assessments of characters and entire environments build the political message of the work: Aragon expresses support for the labor movement, against the prevailing form of the capitalist system in his time, even when the activists of this movement espouse views not as radical as his own. By making women the main characters of the text, he also presents his stance on the feminist movement: women can only be liberated when they actively engage in the labor movement, recognizing the connection between gender inequality and economic stratification of society. The conclusion of such a constructed message is a call to the reader contained in the epilogue:[17]

Your strength is also needed to transform the world.[12]

This appeal is one of several direct authorial comments placed by Aragon in the epilogue of the work.[18]

The significance of collective action is emphasized by the construction of scenes involving crowds in the work, depicted in an extremely vivid manner, as a force with a specific goal, not as a disorganized mass.[19] However, focusing on the general ideology of crowds and their most common beliefs results in a complete abandonment of characterizing individual workers, even achieving their artificial uniformity. Despite this, The Bells of Basel is an important work in the history of French literature addressing wage laborers: for the first time, the world of workers and associated socialist activists was depicted in such a broad way.[20]

In a review by Georges Sadoul that appeared shortly after the publication of The Bells of Basel, this novel was described as the first example of socialist realism in French literature.[21] However, J. Heistein opposes the unequivocal classification of the novel as implementing the Soviet concept of socialist realist novels. Despite the work being based on clear ideological foundations, Aragon retained many features of surrealist writing in The Bells of Basel, primarily the lack of uniformity in style and the overlapping of plotlines (collage technique). This author believes that there is not as clear a contrast between The Bells of Basel and Aragon's earlier work as the writer himself claimed.[22]

Language

[edit]A notable expression of stylistic changes occurring in various parts of the work is the modification of the language of the text. In the first part, Aragon expresses his disdain, at best indifference, towards the lives of the wealthiest French people through linguistic means. Irony and elements of satire disappear in passages dedicated to the experiences of Victor and Catherine. In turn, the epilogue is written in a lofty style, almost akin to an epic, emphasizing the significance of the events described and the entire labor movement. The language of the characters is modified in a special way, with their manner of speaking changing on one hand under the influence of the social environment (widespread use of workers' jargon), and on the other hand – reflecting their personal experiences and reflections.[23]

The Bells of Basel as a historical novel

[edit]Writing the novel, Aragon aimed to depict as faithfully as possible the social life of France on the eve of World War I. However, his political views significantly influenced the selection of readings that would help him understand past events, thereby co-creating the final message of the text. In order to better understand the economic structure of the Third Republic, he analyzed it based on Marxist texts – articles published in the economic section of L'Humanité and Vladimir Lenin's essay Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism.[24] Aragon also incorporated Lenin's views on reformism, anarchism, and the activities of the Second International into the work (views with which he fully identified).[6]

In his work, Aragon refers to authentic events – the Second Moroccan Crisis, the Balkan Wars, the suicide and funeral of Paul and Laura Lafargue – which influenced the attitudes of various social classes in the period preceding World War I. Political events constitute an important axis of the work. According to Garaudy, the rhythm of the work is determined by the growing awareness of the inevitability of war and the successive events leading to its outbreak – even when the characters are not directly involved.[25]

However, particular attention is paid to the taxi drivers' strike in 1911, which is described based on the author's experiences related to another mass labor protest that took place in 1934. At that time, Aragon, a member of the editorial board of L'Humanité, was responsible for daily reports documenting the course of this strike. He drew a number of details contained in the work from there: the image of workers' solidarity and attacks on strikebreakers, police provocation, the death of the driver Bédhomme during the demonstration, and his funeral.[26] Roger Garaudy highly values the part dedicated to the strike, its authenticity, and the strength of expression resulting from it.[26] Zofia Jaremko-Pytowska, however, offers a different assessment, stating that Aragon saturated this part of the novel with details, wanting to include all his own impressions related to the strike.[27]

The culminating point of the work is the description of the congress of the Second International in Basel, contained in the epilogue titled Clara.[28] Aragon provides a monumental description of it, emphasizing the personal qualities, determination, and charisma of many leaders of the International. However, he admits that the political effects of the congress were different from those assumed, and the described leaders were soon to vote in national parliaments for the granting of war credits to governments, thus contrary to the program of the labor movement.[29] Finally, the sound of the titular bells heralds the inevitable outbreak of armed conflict:

It was in vain to think that the cathedral was on the side of the congress, that it was in the cathedral that the word of peace would resound, the sound of the bells relentlessly took on the accent of beating for alarm. They rang for war, for danger.[30]

The Bells of Basel as a novel about love

[edit]Louis Aragon emphasized the importance of female characters and related love plots in his works.[2] Roger Garaudy even argues that love, considered in strict relation to social structure, is the main theme of the work.[2] The first three parts of the novel demonstrate the impossibility of true love in capitalist society, as one of its elements, according to the author, is making women subservient to men. Only in the finale of the work, when Klara Zetkin speaks, Aragon expresses faith in the rebirth of love that will occur in socialist society when women and men truly become equals.[31] True love, therefore, does not rely on entering into successive relationships for financial gain, as Diana de Nettencourt does, nor on free love, as practiced by the rebellious Catherine Simonidze against her own environment.[32] The relationship between two free individuals, genuine devotion to each other, constitutes a natural element of human striving for perfection and happiness.[32]

The Bells of Basel as a coming-of-age novel

[edit]

The second key theme of the work is the problem of ideological transformation, which many intellectuals and artists, including Aragon himself, underwent during his time. As Aragon explained in La Nouvelle Critique in 1949:

In The Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, one sentence struck me, which said that there will come a moment when the best part of the bourgeoisie will join the side of the working class. I wanted to describe the first forms of this transition.[33]

In doing so, the author also described his own ideological evolution – transitioning from the praise of artistic individualism and full freedom of the individual to the advocacy of social engagement on the side of the labor movement.[34]

His expanded alter ego in the work is considered to be the character of Catherine.[35] This character, the daughter of a wealthy industrialist from Baku, tries to completely break ties with her social class, whose way of life she finds repugnant. Initially, she seeks freedom in anarchism and free love, but the awareness of being dependent on the money sent to her by her father, her sole means of support, makes her realize the futility of these attempts. Catherine is also unable to fully integrate into the working-class environment, where the chauffeur Victor Deyhanin tries to introduce her. She only looks at the striking workers with curiosity because their motivation, typically economic, is not synonymous with her search for the meaning of life.[36] Some of Catherine's behaviors have clear origins in the doubts of the writer himself from the period when he participated in formulating surrealist doctrine. The surrealists wanted to reject all cultural achievements of previous generations – similarly, Simonidze is outraged that a funeral march by Frédéric Chopin is played at the funeral of a slain worker.[37] Moreover, in Catherine's conversation with Victor, Aragon presents a negative answer to the question previously posed by the surrealists about the meaning of suicide.[37]

However, Catherine is unable to completely break away from her environment. Expelled from France, although she makes contact with the British left, she still behaves like an observer of the lives of workers, rather than an active participant,[38] although the narrator suggests that she ultimately adopted socialist views as her own. Her attitude, full of fluctuations until the end, is also criticized and contrasted with the behavior of Clara Zetkin.[39] Catherine's transformation is more spiritual and internal than practical. Her subsequent changes largely occur under the influence of chance – the character accidentally comes across a procession of striking workers in Cluses, then incidentally sees an anarchist poster, and finally, under similar circumstances, forms a relationship with Victor. Aragon therefore does not conclude the description of the process of Catherine's transformations with a definitive conclusion. The first character in the works of this writer whose "journey to socialism" will be depicted in its entirety will only be Armand, the main character of Les Beaux Quartiers.[40]

Reception

[edit]Immediately upon its release, the novel was described by G. Sadoul as a socialist realist work.[41] The work was mainly evaluated by critics associated with the French Communist Party and by Soviet reviewers, in terms of the ideological realization of communist demands in literature and art. These authors received the novel with mixed feelings. The portrayal of the possessing classes and left-wing activists did not arouse controversy among them, but there were accusations of an unwitting idealization of the anarchist movement in the second part of the work. Some Soviet critics considered the novel as evidence that the French communist left did not yet have a fully developed program.[42]

Later criticism highly praised especially the first part, as a portrayal of the daily life of the wealthiest French people depicted through a series of seemingly unrelated scenes.[43]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Garaudy (1965, p. 316)

- ^ a b c d Garaudy (1965, p. 317)

- ^ Jaremko-Pytowska (1963, pp. 73–76)

- ^ Jaremko-Pytowska (1963, p. 77)

- ^ Garaudy (1965, p. 321)

- ^ a b Garaudy (1965, p. 322)

- ^ Aragon (1936, p. 5)

- ^ Jaremko-Pytowska (1963, p. 82)

- ^ Garaudy (1965, p. 325)

- ^ a b Garaudy (1965, p. 324)

- ^ Jaremko-Pytowska (1963, p. 79)

- ^ a b Aragon (1936, p. 318)

- ^ Garaudy (1965, p. 341)

- ^ Garaudy (1965, pp. 324–325)

- ^ Garaudy (1965, pp. 325–326)

- ^ Jaremko-Pytowska (1963, pp. 90–91)

- ^ Garaudy (1965, pp. 330–332, 336)

- ^ Garaudy (1965, p. 336)

- ^ Garaudy (1965, p. 339)

- ^ Garaudy (1965, p. 340)

- ^ Garaudy (1965, p. 345)

- ^ Heistein (1991, p. 240)

- ^ Garaudy (1965, pp. 343–345)

- ^ Garaudy (1965, pp. 321–322)

- ^ Garaudy (1965, p. 327)

- ^ a b Garaudy (1965, p. 323)

- ^ Jaremko-Pytowska (1963, p. 86)

- ^ Jaremko-Pytowska (1963, pp. 88, 91)

- ^ Jaremko-Pytowska (1963, p. 89)

- ^ Aragon (1936, p. 319)

- ^ Garaudy (1965, pp. 317–318)

- ^ a b Garaudy (1965, p. 318)

- ^ Garaudy (1965, p. 320)

- ^ Garaudy (1965, pp. 320–321)

- ^ Jaremko-Pytowska (1963, p. 84)

- ^ Garaudy (1965, pp. 329–332)

- ^ a b Garaudy (1965, p. 333)

- ^ Flower (1983, p. 113)

- ^ Garaudy (1965, p. 334)

- ^ Garaudy (1965, pp. 335–336)

- ^ Flower (1983, p. 108)

- ^ Flower (1983, pp. 108–109)

- ^ Flower (1983, p. 109)

Bibliography

[edit]- Aragon, Louis (1936). Dzwony Bazylei. Warsaw: W. J. Przeworski.

- Flower, J. (1983). Literature and the Left in France. London: The Macmillan Press.

- Garaudy, R. (1965). Droga Aragona. Od nadrealizmu do świata rzeczywistego. Warsaw: Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy.

- Heistein, J. (1991). Literatura francuska XX wieku [French literature of the 20th century] (in Polish). Warsaw: Państwowe Wydaw. Scientific. ISBN 83-01-10150-4.

- Jaremko-Pytowska, Z. (1963). Louis Aragon. Warsaw: Wiedza Powszechna.

- Lecherbonnier, B. (1971). Aragon. Paris: Bordas.