Эфиопия

Федеративная Демократическая Республика Эфиопия | |

|---|---|

| Гимн: Двигайся вперед, дорогая мать Эфиопия. «Wedefīt Gesigishī Wid Inat ītiyop'iy» (На английском языке: « Марш вперед, дорогая Мать Эфиопия » ) | |

| |

| Capital and largest city | Addis Ababa 9°1′N 38°45′E / 9.017°N 38.750°E |

| Official languages | |

| Ethnic groups | |

| Religion (2016[7]) |

|

| Demonym(s) | Ethiopian |

| Government | Federal parliamentary republic[8] |

| Sahle-Work Zewde | |

| Abiy Ahmed | |

| Temesgen Tiruneh | |

| Tewodros Mihret | |

| Legislature | Federal Parliamentary Assembly |

| House of Federation | |

| House of Peoples' Representatives | |

| Formation | |

• Dʿmt | 980 BC |

| 400 BC | |

| 1270 | |

| 7 May 1769 | |

| 11 February 1855 | |

| 1904 | |

| 9 May 1936 | |

| 31 January 1942 | |

• Derg | 12 September 1974 |

| 22 February 1987 | |

| 28 May 1991 | |

| 21 August 1995 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 1,112,000[9] km2 (429,000 sq mi) (26th) |

• Water (%) | 0.7 |

| Population | |

• 2024 estimate | |

• 2007 census | |

• Density | 92.7/km2 (240.1/sq mi) (123rd) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2015) | medium |

| HDI (2022) | low (176th) |

| Currency | Birr (ETB) |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (EAT) |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +251 |

| ISO 3166 code | ET |

| Internet TLD | .et |

Эфиопия , [а] официально Федеративная Демократическая Республика Эфиопия — страна, не имеющая выхода к морю, расположенная в регионе Африканского Рога в Восточной Африке . Она граничит с Эритреей на севере , Джибути на северо-востоке , Сомали на востоке , Кенией на юге , Южным Суданом на западе и Суданом на северо-западе . Эфиопия занимает территорию площадью 1 112 000 квадратных километров (472 000 квадратных миль). [14] По состоянию на 2024 год [update]В ней проживает около 129 миллионов жителей, что делает ее 13-й по численности населения страной в мире, 2-й по численности населения в Африке после Нигерии и самой густонаселенной страной на Земле, не имеющей выхода к морю. [15] [16] Столица страны и крупнейший город Аддис-Абеба находится в нескольких километрах к западу от Восточно-Африканского разлома , который разделяет страну на Африканскую и Сомалийскую тектонические плиты . [17]

Анатомически современные люди вышли из современной Эфиопии и отправились на Ближний Восток и в другие места в период среднего палеолита . [18][19][20][21][22] Southwestern Ethiopia has been proposed as a possible homeland of the Afroasiatic language family.[23] In 980 BC, the Kingdom of D'mt extended its realm over Eritrea and the northern region of Ethiopia, while the Kingdom of Aksum maintained a unified civilization in the region for 900 years. Christianity was embraced by the kingdom in 330,[24] and Islam arrived by the first Hijra in 615.[25] After the collapse of Aksum in 960, the Zagwe dynasty ruled the north-central parts of Ethiopia until being overthrown by Yekuno Amlak in 1270, inaugurating the Ethiopian Empire and the Solomonic dynasty, claimed descent from the biblical Solomon and Queen of Sheba under their son Menelik I. By the 14th century, the empire had grown in prestige through territorial expansion and fighting against adjacent territories; most notably, the Ethiopian–Adal War (1529–1543) contributed to fragmentation of the empire, which ultimately fell under a decentralization known as Zemene Mesafint in the mid-18th century. Emperor Tewodros II ended Zemene Mesafint at the beginning of his reign in 1855, marking the reunification and modernization of Ethiopia.[26]

From 1878 onwards, Emperor Menelik II launched a series of conquests known as Menelik's Expansions, which resulted in the formation of Ethiopia's current border. Externally, during the late 19th century, Ethiopia defended itself against foreign invasions, including from Egypt and Italy; as a result, Ethiopia preserved its sovereignty during the Scramble for Africa. In 1936, Ethiopia was occupied by Fascist Italy and annexed with Italian-possessed Eritrea and Somaliland, later forming Italian East Africa. In 1941, during World War II, it was occupied by the British Army, and its full sovereignty was restored in 1944 after a period of military administration. The Derg, a Soviet-backed military junta, took power in 1974 after deposing Emperor Haile Selassie and the Solomonic dynasty, and ruled the country for nearly 17 years amidst the Ethiopian Civil War. Following the dissolution of the Derg in 1991, the Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) dominated the country with a new constitution and ethnic-based federalism. Since then, Ethiopia has suffered from prolonged and unsolved inter-ethnic clashes and political instability marked by democratic backsliding. From 2018, regional and ethnically based factions carried out armed attacks in multiple ongoing wars throughout Ethiopia.[27]

Ethiopia is a multi-ethnic state with over 80 different ethnic groups. Christianity is the most widely professed faith in the country, with significant minorities of the adherents of Islam and a small percentage to traditional faiths. This sovereign state is a founding member of the UN, the Group of 24, the Non-Aligned Movement, the Group of 77, and the Organisation of African Unity. Addis Ababa is the headquarters of the African Union, the Pan African Chamber of Commerce and Industry, the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, the African Standby Force and many of the global non-governmental organizations focused on Africa. Ethiopia became a full member of BRICS in 2024.[28] Ethiopia is one of the least developed countries but is sometimes considered an emerging power,[29][30] having the fastest economic growth in Sub-Saharan African countries because of foreign direct investment in expansion of agricultural and manufacturing industries;[31] agriculture is the country's largest economic sector, accounting for 36% of the gross domestic product as of 2020.[32] However, in terms of per capita income and the Human Development Index,[33] the country is regarded as poor, with high rates of poverty,[34] poor respect for human rights, widespread ethnic discrimination, and a literacy rate of only 49%.[35]

Etymology[edit]

The name Ethiopia (ኢትዮጵያ) comes from the name of the first King of Ethiopia, Ethiop, or Ethiopis.

Ayele Berkerie explains:

According to an Ethiopian tradition, the term Ethiopia is derived from the word Ethiopis, a name of the Ethiopian king, the seventh in the ancestral lines. Metshafe Aksum or the Ethiopian Book of Aksum identifies Itiopis as the twelfth king of Ethiopia and the father of Aksumawi. The Ethiopians pronounce Ethiopia እትዮጵያ with a Sades or the sixth sound እ as in incorporate and the graph ጰ has no equivalent in English or Latin graphs. Ethiopis is believed to be the twelfth direct descendant of Adam. His father is identified as Kush, while his grandfather is known as Kam.[36]

In the 15th-century Ge'ez Book of Axum, the name is ascribed to a legendary individual called Ityopp'is. He was an extra-biblical son of Cush, son of Ham, said to have founded the city of Axum.[37]

The Greek name Αἰθιοπία (from Αἰθίοψ, "an Ethiopian") is a compound word, later explained as derived from the Greek words αἴθω and ὤψ (eithō "I burn" + ōps "face"). According to the Liddell-Scott Jones Greek-English Lexicon, the designation properly translates as burnt-face in noun form and red-brown in adjectival form.[38] The historian Herodotus used the appellation to denote those parts of Africa south of the Sahara that were then known within the Ecumene (habitable world).[39] The earliest mention of the term is found in the works of Homer, where it is used to refer to two people groups, one in Africa and one in the east from eastern Turkey to India.[40] This Greek name was borrowed into Amharic as ኢትዮጵያ, ʾĪtyōṗṗyā.

In Greco-Roman epigraphs, Aethiopia was a specific toponym for ancient Nubia.[41] At least as early as c. 850,[42] the name Aethiopia also occurs in many translations of the Old Testament in allusion to Nubia. The ancient Hebrew texts identify Nubia instead as Kush.[43] However, in the New Testament, the Greek term Aithiops does occur, referring to a servant of the Kandake, the queen of Kush.[44]

Following the Hellenic and biblical traditions, the Monumentum Adulitanum, a 3rd-century inscription belonging to the Aksumite Empire, indicates that Aksum's ruler governed an area that was flanked to the west by the territory of Ethiopia and Sasu. The Aksumite King Ezana eventually conquered Nubia the following century, and the Aksumites thereafter appropriated the designation "Ethiopians" for their own kingdom. In the Ge'ez version of the Ezana inscription, Aἰθίοπες is equated with the unvocalized Ḥbšt and Ḥbśt (Ḥabashat), and denotes for the first time the highland inhabitants of Aksum. This new demonym was subsequently rendered as ḥbs ('Aḥbāsh) in Sabaic and as Ḥabasha in Arabic.[41] Derivatives of this are used in some languages that use loanwords from Arabic, for example in Malay Habsyah.

In English, and generally outside of Ethiopia, the country was historically known as Abyssinia. This toponym was derived from the Latinized form of the ancient Habash.[45]

History[edit]

Prehistory[edit]

Several important finds have propelled Ethiopia and the surrounding region to the forefront of palaeontology. The oldest hominid discovered to date in Ethiopia is the 4.2 million-year-old Ardipithecus ramidus (Ardi) found by Tim D. White in 1994.[46] The most well-known hominid discovery is Australopithecus afarensis (Lucy). Known locally as Dinkinesh, the specimen was found in the Awash Valley of Afar Region in 1974 by Donald Johanson, and is one of the most complete and best-preserved adult Australopithecine fossils ever uncovered. Lucy's taxonomic name refers to the region where the discovery was made. This hominid is estimated to have lived 3.2 million years ago.[47][48][49]

Ethiopia is also considered one of the earliest sites of the emergence of anatomically modern humans, Homo sapiens. The oldest of these local fossil finds, the Omo remains, were excavated in the southwestern Omo Kibish area and have been dated to the Middle Paleolithic, around 200,000 years ago.[50] Additionally, skeletons of Homo sapiens idaltu were found at a site in the Middle Awash valley. Dated to approximately 160,000 years ago, they may represent an extinct subspecies of Homo sapiens, or the immediate ancestors of anatomically modern humans.[51] Archaic Homo sapiens fossils excavated at the Jebel Irhoud site in Morocco have since been dated to an earlier period, about 300,000 years ago,[52] while Omo-Kibish I (Omo I) from southern Ethiopia is the oldest anatomically modern Homo sapiens skeleton currently known (196 ± 5 kya).[53]

According to some linguists, the first Afroasiatic-speaking populations arrived in the region during the ensuing Neolithic era from the family's proposed urheimat ("original homeland") in the Nile Valley,[54] or the Near East.[55] The majority of scholars today propose that the Afroasiatic family developed in northeast Africa because of the higher diversity of lineages in that region, a telltale sign of linguistic origin.[56][57][58]

In 2019, archaeologists discovered a 30,000-year-old Middle Stone Age rock shelter at the Fincha Habera site in Bale Mountains at an elevation of 3,469 metres (11,381 feet) above sea level. At this high altitude, humans are susceptible both to hypoxia and to extreme weather. According to a study published in the journal Science, this dwelling is proof of the earliest permanent human occupation at high altitude yet discovered. Thousands of animal bones, hundreds of stone tools, and ancient fireplaces were discovered, revealing a diet that featured giant mole rats.[59][60][61][62][63][64][65]

Evidence of some of the earliest known stone-tipped projectile weapons (a characteristic tool of Homo sapiens), the stone tips of javelins or throwing spears, were discovered in 2013 at the Ethiopian site of Gademotta, which date to around 279,000 years ago.[66] In 2019, additional Middle Stone Age projectile weapons were found at Aduma, dated 100,000–80,000 years ago, in the form of points considered likely to belong to darts delivered by spear throwers.[67]

Antiquity[edit]

In 980 BC, Dʿmt was established in present-day Eritrea and the northern part of Ethiopia in Tigray and Amhara regions, and is widely believed to be the successor state to Punt. This polity's capital was located at Yeha in what is now northern Ethiopia. Most modern historians consider this civilization to be a native Ethiopian one, although in earlier times many suggested it was Sabaean-influenced because of the latter's hegemony of the Red Sea.[68]

Other scholars regard Dʿmt as the result of a union of Afroasiatic-speaking cultures of the Cushitic and Semitic branches; namely, local Agaw peoples and Sabaeans from Southern Arabia. However, Ge'ez, the ancient Semitic language of Ethiopia, is thought to have developed independently from the Sabaean language. As early as 2000 BC, other Semitic speakers were living in Ethiopia and Eritrea where Ge'ez developed.[69][70] Sabaean influence is now thought to have been minor, limited to a few localities, and disappearing after a few decades or a century. It may have been a trading or military colony in alliance with the Ethiopian civilization of Dʿmt or some other proto-Axumite state.[68]

After the fall of Dʿmt during the 4th century BC, the Ethiopian plateau came to be dominated by smaller successor kingdoms. In the 1st century AD, the Kingdom of Aksum emerged in what is now Tigray Region and Eritrea. According to the medieval Book of Axum, the kingdom's first capital, Mazaber, was built by Itiyopis, son of Cush.[37] Aksum would later at times extend its rule into Yemen on the other side of the Red Sea.[71] The Persian prophet Mani listed Axum with Rome, Persia, and China as one of the four great powers of his era, during the 3rd century.[72] It is also believed that there was a connection between Egyptian and Ethiopian churches. There is diminutive evidence that the Aksumites were associated with the Queen of Sheba, via their royal inscription.[73]

Around 316 AD, Frumentius and his brother Edesius from Tyre accompanied their uncle on a voyage to Ethiopia. When the vessel stopped at a Red Sea port, the natives killed all the travellers except the two brothers, who were taken to the court as slaves. They were given positions of trust by the monarch, and they converted members of the royal court to Christianity. Frumentius became the first bishop of Aksum.[74] A coin dated to 324 shows that Ethiopia was the second country to officially adopt Christianity (after Armenia did so in 301), although the religion may have been at first confined to court circles; it was the first major power to do so. The Aksumites were accustomed to the Greco-Roman sphere of influence, but embarked on significant cultural ties and trade connections between the Indian subcontinent and the Roman Empire via the Silk Road, primarily exporting ivory, tortoise shell, gold and emeralds, and importing silk and spices.[73][75]

Middle Ages[edit]

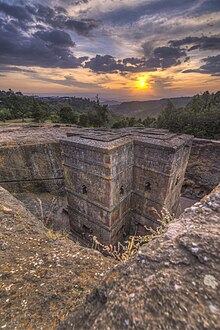

The kingdom adopted the name "Ethiopia" during the reign of Ezana in the 4th century. After the conquest of Kingdom of Kush in 330, the Aksumite territory reached its peak between the 5th and 6th centuries.[68] This period was interrupted by several incursions into the South Arabian protectorate, including Jewish Dhu Nuwas of the Himyarite Kingdom and the Aksumite–Persian wars. In 575, the Aksumites besieged and retook Sana'a following the assassination of its governor Sayf ibn Dhī Yazan. The Red Sea was left to the Rashidun Caliphate in 646, and the port city of Adulis was plundered by Arab Muslims in the 8th century; along with irrevocable land degradation, claimed climate change and sporadic rainfall precipitation from 730 to 760,[76] these factors likely caused the kingdom to decline in power as part of an important trade route.[68][77] Aksum came to an end in 960 when Queen Gudit defeated the last king of Aksum.[78] In response, the remnant of the Aksumite population to shift into the southern region and establish the Zagwe dynasty, changing its capital to Lalibela.[79] Zagwe's rule ended when an Amhara noble man Yekuno Amlak revolted against King Yetbarak and established the Ethiopian Empire (known by exonym "Abyssinia").

The Ethiopian Empire initiated territorial expansion under the leadership of Amda Seyon I. He launched campaigns against his Muslim adversaries to the east, resulting in a significant shift in the balance of power in favor of the Christians for the next two centuries. After Amda Seyon's successful eastern campaigns, most of the Muslim principalities in the Horn of Africa came under the suzerainty of the Ethiopian Empire. Stretching from Gojjam to the Somali Coast in Zelia.[80] Among these Muslim entities was the Sultanate of Ifat. During the reign of Emperor Zara Yaqob, the Ethiopian Empire reached its pinnacle. His rule was marked by the consolidation of territorial acquisitions from earlier rulers, the oversight of the construction of numerous churches and monasteries, the active promotion of literature and art, and the strengthening of central imperial authority.[81][82][83] Ifat's successor, the Adal Sultanate,[84] tried to conquer Ethiopia during the Ethiopian–Adal War, but was ultimately defeated at the 1543 Battle of Wayna Daga.[85]

By the 16th century, an influx of migration by ethnic Oromo into northern parts of the region fragmented the empire's power. Embarking from present-day Guji and Borena Zone, the Oromos were largely motivated by several folkloric conceptions—beginning with Moggaasaa[86] and Liqimssa—many of whom related to their raids. This persisted until gada of Meslé.[87][88] According to Abba Bahrey, the earliest expansion occurred under Emperor Dawit II (luba Melbah), when they encroached to Bale before invading Adal Sultanate.[89]

Ethiopia saw major diplomatic contact with Portugal from the 17th century, mainly related to religion. Beginning in 1555,[90] Portuguese Jesuits attempted to develop Roman Catholicism as the state religion. After several failures, they sent several missionaries in 1603, including the most influential, Spanish Jesuit Pedro Paez.[91] Under Emperor Susenyos I, Roman Catholicism became the state religion of the Ethiopian Empire in 1622.[92] This decision caused an uprising by the Orthodox populace.[93]

Early Modern Period (1632–1855)[edit]

In 1632, Emperor Fasilides halted Roman Catholic state administration, restoring Orthodox Tewahedo as the state religion.[92] Fasilides' reign solidified imperial power, relocating the capital to Gondar in 1636, marking the beginning of the "Gondarine period".[94] He expelled Jesuits, reclaimed lands, and relocated them to Fremona. During his rule, Fasilides constructed the iconic royal fortress, Fasil Ghebbi, built forty-four churches,[95] and revived Ethiopian art. He is also credited with building seven stone bridges over the Blue Nile River.[96]

Gondar's power declined after the death of Iyasu I in 1706. Following Iyasu II's death in 1755, Empress Mentewab brought her brother, Ras Wolde Leul, to Gondar, making him Ras Bitwaded. This led to regnal conflict between Mentewab's Quaregnoch and the Wollo group led by Wubit. In 1767, Ras Mikael Sehul, a regent in Tigray Province, seized Gondar, killing the child Iyoas I in 1769, the reigning emperor, and installed 70-year-old Yohannes II.[97]

Between 1769 and 1855, Ethiopia witnessed the Zemene Mesafint or "Age of Princes," a period of isolation. Emperors became figureheads, controlled by regional lords and noblemen like Ras Mikael Sehul, Ras Wolde Selassie of Tigray, and by the Yejju Oromo dynasty of the Wara Sheh, including Ras Gugsa of Yejju. Before the Zemene Mesafint, Emperor Iyoas I had introduced the Oromo language (Afaan Oromo) at court, replacing Amharic.[98][99]

Age of Imperialism (1855–1916)[edit]

Ethiopian isolationism ended following a British mission that concluded with an alliance between the two nations, but it was not until 1855 that the Amhara kingdoms of northern Ethiopia (Gondar, Gojjam, and Shewa) were briefly united after the power of the emperor was restored beginning with the reign of Tewodros II.[100][101] Tewodros II began a process of consolidation, centralisation, and state-building that would be continued by succeeding emperors. This process reduced the power of regional rulers, restructured the empire's administration, and created a professional army. These changes created the basis for establishing the effective sovereignty and territorial integrity of the Ethiopian state.[102] In 1875 and 1876, Ottoman and Egyptian forces, accompanied by many European and American advisors, twice invaded Abyssinia but were initially defeated.[103] From 1885 to 1889 (under Yohannes IV), Ethiopia joined the Mahdist War allied to Britain, Turkey, and Egypt against the Sudanese Mahdist State. In 1887, Menelik II, king of Shewa, invaded the Emirate of Harar after his victory at the Battle of Chelenqo.[104] On 10 March 1889, Yohannes IV was killed by the Sudanese Khalifah Abdullah's army whilst leading his army in the Battle of Gallabat.[105]

Ethiopia, in roughly its current form, began under the reign of Menelik II, who was Emperor from 1889 until his death in 1913. From his base in the central province of Shewa, Menelik set out to annex territories to the south, east, and west[106] — areas inhabited by the Oromo, Sidama, Gurage, Welayta, and other peoples.[107] He achieved this with the help of Ras Gobana Dacche's Shewan Oromo militia, which occupied lands that had not been held since Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi's war, as well as other areas that had never been under Ethiopian rule.[108]

For his leadership, despite opposition from more traditional elements of society, Menelik II was heralded as a national hero. He had signed the Treaty of Wuchale with Italy in May 1889, by which Italy would recognize Ethiopia's sovereignty so long as Italy could control an area north of Ethiopia (now part of modern Eritrea). In return, Italy was to provide Menelik with weapons and support him as emperor. The Italians used the time between the signing of the treaty and its ratification by the Italian government to expand their territorial claims. This First Italo–Ethiopian War culminated in the Battle of Adwa on 1 March 1896, in which Italy's colonial forces were defeated by the Ethiopians.[107][109] During this time, about a third of the population died in the Great Ethiopian Famine (1888 to 1892).[110][111] and the rinderpest swept through the area, destroying much of the herd economy. On 11 October 1897, Ethiopia adopted the colours of the pan-African flag with green, yellow and red stripes in representation of pan-Africanist ideology.

Haile Selassie I era (1916–1974)[edit]

The early 20th century was marked by the reign of Emperor Haile Selassie (Ras Tafari). He came to power after Lij Iyasu was deposed, and undertook a nationwide modernization campaign from 1916 when he was made a Ras and Regent (Inderase) for the Empress Regnant Zewditu, and became the de facto ruler of the Ethiopian Empire. Following Zewditu's death, on 2 November 1930, he succeeded her as emperor.[112] In 1931, Haile Selassie endowed Ethiopia with its first-ever Constitution in emulation of Imperial Japan's 1890 Constitution.[113]The independence of Ethiopia was interrupted by the Second Italo-Ethiopian War, beginning when it was invaded by Fascist Italy in early October 1935, and by subsequent Italian rule of the country (1936–1941) after Italian victory in the war.[114] Italy, however never managed to secure the country, due to resistance from the Arbegnoch, making Ethiopia and Liberia the only African nations to never be colonized.[115] Following the entry of Italy into World War II, British Empire forces, together with the Arbegnoch, liberated Ethiopia in the course of the East African campaign in 1941. The country was placed under British military administration, and then Ethiopia's full sovereignty was restored with the signing of the Anglo-Ethiopian Agreement in December 1944.[116]

On 24 October 1945, Ethiopia became a founding member of the United Nations. In 1952, Haile Selassie orchestrated a federation with Eritrea. He dissolved this in 1962 and annexed Eritrea, resulting in the Eritrean War of Independence.[citation needed] Haile Selassie also played a leading role in the formation of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU).[117] Opinion within Ethiopia turned against Haile Selassie, owing to the worldwide 1973 oil crisis causing a sharp increase in gasoline prices starting on 13 February 1974, leading to student and worker protests.[118] The feudal oligarchical cabinet of Aklilu Habte-Wold was toppled, and a new government was formed with Endelkachew Makonnen serving as Prime Minister.[119]

Derg era (1974–1991)[edit]

Haile Selassie's rule ended on 12 September 1974, when he was deposed by the Derg, a committee made up of military and police officers.[120] After the execution of 60 former government and military officials,[121] the new Provisional Military Administrative Council abolished the monarchy in March 1975 and established Ethiopia as a Marxist-Leninist state.[122] The abolition of feudalism, increased literacy, nationalization, and sweeping land reform including the resettlement and villagization from the Ethiopian Highlands became priorities.[123]

After a power struggle in 1977, Mengistu Halie Mariam gained undisputed leadership of the Derg.[124] In 1977, Somalia, which had previously been receiving assistance and arms from the USSR, invaded Ethiopia in the Ogaden War, capturing part of the Ogaden region. Ethiopia recovered it after it began receiving massive military aid from the Soviet bloc countries.[125][126][127] By the end of the seventies, Mengistu presided over the second-largest army in all of sub-Saharan Africa, as well as a formidable air force and navy.

In 1976–78, up to 500,000 were killed as a result of the Red Terror,[128] a violent political repression campaign by the Derg against various opposition groups.[129][130][131] In 1987, the Derg dissolved itself and established the People's Democratic Republic of Ethiopia (PDRE) upon the adoption of the 1987 Constitution of Ethiopia.[132] A 1983–85 famine affected around 8 million people, resulting in 1 million dead. Insurrections against authoritarian rule sprang up, particularly in the northern regions of Eritrea and Tigray. The Tigray People's Liberation Front (TPLF) merged with other ethnically based opposition movements in 1989, to form the Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF).[133]

The collapse of Marxism–Leninism during the revolutions of 1989 coincided with the Soviet Union stopping aid to Ethiopia altogether in 1990.[134][135][136] EPRDF forces advanced on Addis Ababa in May 1991, and Mengistu fled the country and was granted asylum in Zimbabwe.[137][138]

Federal Democratic Republic (1991–present)[edit]

In July 1991, the EPRDF convened a National Conference to establish the Transitional Government of Ethiopia composed of an 87-member Council of Representatives and guided by a national charter that functioned as a transitional constitution.[139] In 1994, a new constitution was written that established a parliamentary republic with a bicameral legislature and a judicial system.[140]

In April 1993, Eritrea gained independence from Ethiopia after a national referendum.[141] In May 1998, a border dispute with Eritrea led to the Eritrean–Ethiopian War, which lasted until June 2000 and cost both countries an estimated $1 million a day.[142] This had a negative effect on Ethiopia's economy, and a border conflict between the two countries would continue until 2018.[143][144] As of 2018, further civil war in Ethiopia continues, mainly due to destabilization of the country.

Ethnic violence rose during the late 2010s and early 2020s,[145][146] with various clashes and conflicts leading to millions of Ethiopians being displaced.[147][148][149]

The federal government decided that elections for 2020 (later being rescheduled to 2021) be cancelled, due to health and safety concerns about COVID-19.[150] The Tigray Region's TPLF opposed this, and proceeded to hold elections anyway on 9 September 2020.[151][152] Relations between the federal government and Tigray deteriorated rapidly,[153] and in November 2020, Ethiopia began a military offensive in Tigray in response to attacks on army units stationed there, marking the beginning of the Tigray War.[154][155] By March 2022, as many as 500,000 people had died as a result of violence and famine.[156][157][158] After a number of peace and mediation proposals in the intervening years, Ethiopia and the Tigrayan rebel forces agreed to a cessation of hostilities on 2 November 2022.[159] Coupled with OLA insurgency, the federal government relations with Fano militias, who previously allied to the government in the Tigray War, deteriorated in mid-2023, resulting in War in Amhara. According to reports conducted by the Ethiopian Human Rights Commission (EHRC), mass human rights violations carried out by ENDF troops including door-to-door searches, extrajudicial killings, massacres and detentions. Notable incident includes the Merawi massacre in early 2024, which left 50 to 100 residents deaths in Merawi town in Amhara Region.[160][161]

Geography[edit]

At 1,104,300 square kilometres (426,372.61 sq mi),[162] Ethiopia is the world's 28th-largest country, comparable in size to Bolivia. It lies between the 3rd parallel north and the 15th parallel north and longitudes 33rd meridian east and 48th meridian east.

The major portion of Ethiopia lies in the Horn of Africa, which is the easternmost part of the African landmass. The territories that have frontiers with Ethiopia are Eritrea to the north and then, moving in a clockwise direction, Djibouti, Somalia, Kenya, South Sudan and Sudan. Within Ethiopia is a vast highland complex of mountains and dissected plateaus divided by the Great Rift Valley, which runs generally southwest to northeast and is surrounded by lowlands, steppes, or semi-desert. There is a great diversity of terrain with wide variations in climate, soils, natural vegetation and settlement patterns.

Ethiopia is an ecologically diverse country, ranging from the deserts along the eastern border to the tropical forests in the south to extensive Afromontane in the northern and southwestern parts. Lake Tana in the north is the source of the Blue Nile. It also has many endemic species, notably the gelada, the walia ibex and the Ethiopian wolf ("Simien fox"). The wide range of altitude has given the country a variety of ecologically distinct areas, and this has helped to encourage the evolution of endemic species in ecological isolation.

The nation is a land of geographical contrasts, ranging from the vast fertile west, with its forests and numerous rivers, to the world's hottest settlement of Dallol in its north. The Ethiopian Highlands are the largest continuous mountain ranges in Africa, and the Sof Omar Caves contains the largest cave on the continent. Ethiopia also has the second-largest number of UNESCO World Heritage Sites in Africa.[163]

Climate[edit]

The predominant climate type is tropical monsoon, with wide topographic-induced variation. The Ethiopian Highlands cover most of the country and have a climate which is generally considerably cooler than other regions at similar proximity to the Equator. Most of the country's major cities are located at elevations of around 2,000–2,500 m (6,562–8,202 ft) above sea level, including historic capitals such as Gondar and Axum. The modern capital, Addis Ababa, is situated on the foothills of Mount Entoto at an elevation of around 2,400 metres (7,900 ft). It experiences a mild climate year round. With temperatures fairly uniform year round, the seasons in Addis Ababa are largely defined by rainfall: a dry season from October to February, a light rainy season from March to May, and a heavy rainy season from June to September. The average annual rainfall is approximately 1,200 millimetres (47 in).

There are on average seven hours of sunshine per day. The dry season is the sunniest time of the year, though even at the height of the rainy season in July and August there are still usually several hours per day of bright sunshine. The average annual temperature in Addis Ababa is 16 °C (60.8 °F), with daily maximum temperatures averaging 20–25 °C (68.0–77.0 °F) throughout the year, and overnight lows averaging 5–10 °C (41.0–50.0 °F).

Most major cities and tourist sites in Ethiopia lie at a similar elevation to Addis Ababa and have a comparable climate. In less elevated regions, particularly the lower lying Ethiopian xeric grasslands and shrublands in the east of Ethiopia, the climate can be significantly hotter and drier. Dallol, in the Danakil Depression in this eastern zone, has the world's highest average annual temperature of 34 °C (93.2 °F).

Ethiopia is vulnerable to many of the effects of climate change. These include increases in temperature and changes in precipitation. Climate change in these forms threatens food security and the economy, which is agriculture based.[166] Many Ethiopians have been forced to leave their homes and travel as far as the Gulf, Southern Africa and Europe.[167]

Since April 2019, the Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed has promoted Beautifying Sheger, a development project that aims to reduce the negative effects of climate change – among other things – in the capital city Addis Ababa.[168] In the following May, the government held "Dine for Sheger", a fundraising event in order to cover some of the $1 billion needed through the public.[169] $25 million was raised through the expensive event, both through the cost of attending and donations.[170] Two Chinese railway companies under the Belt and Road Initiative between China and Ethiopia had supplied funds to develop 12 of the total 56 kilometres.[171]

Biodiversity[edit]

Ethiopia is a global centre of avian diversity. To date more than 856 bird species have been recorded in Ethiopia, twenty of which are endemic to the country.[172] Sixteen species are endangered or critically endangered. Many of these birds feed on butterflies, like the Bicyclus anynana.[173][full citation needed]

Historically, throughout the African continent, wildlife populations have been rapidly declining due to logging, civil wars, pollution, poaching, and other human factors.[174] A 17-year-long civil war, along with severe drought, negatively affected Ethiopia's environmental conditions, leading to even greater habitat degradation.[175] Habitat destruction is a factor that leads to endangerment. When changes to a habitat occur rapidly, animals do not have time to adjust. Human impact threatens many species, with greater threats expected as a result of climate change induced by greenhouse gases.[176] With carbon dioxide emissions in 2010 of 6,494,000 tonnes, Ethiopia contributes just 0.02% to the annual human-caused release of greenhouse gases.[177]

Ethiopia has 31 endemic species of mammals.[178] Ethiopia has many species listed as critically endangered and vulnerable to global extinction. The threatened species in Ethiopia can be broken down into three categories (based on IUCN ratings): critically endangered, endangered, and vulnerable.[178]

Ethiopia is one of the eight fundamental and independent centres of origin for cultivated plants in the world.[179] However, deforestation is a major concern for Ethiopia as studies suggest loss of forest contributes to soil erosion, loss of nutrients in the soil, loss of animal habitats, and reduction in biodiversity. At the beginning of the 20th century, around 420,000 km2 (or 35%) of Ethiopia's land was covered by trees, but recent research indicates that forest cover is now approximately 11.9% of the area.[180] The country had a 2018 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 7.16/10, ranking it 50th globally out of 172 countries.[181]

Ethiopia loses an estimated 1,410 km2 of natural forests each year due to firewood collection, conversion to farmland, overgrazing, and use of forest wood for building material. Between 1990 and 2005 the country lost approximately 21,000 km2 of forests.[182] Current government programs to control deforestation consist of education, promoting reforestation programs, and providing raw materials which are alternatives to timber. In rural areas the government also provides non-timber fuel sources and access to non-forested land to promote agriculture without destroying forest habitat.[183]

Organizations such as SOS and Farm Africa are working with the federal government and local governments to create a system of forest management.[184]

Government and politics[edit]

Government[edit]

Ethiopia is a federal parliamentary republic, wherein the Prime Minister is the head of government, and the President is the head of state but with largely ceremonial powers. Executive power is exercised by the government and federal legislative power vested in both the government and the two chambers of parliament. The House of Federation is the upper chamber of the bicameral legislature with 108 seats, and the lower chamber is the House of Peoples' Representatives (HoPR) with 547 seats. The House of Federation is chosen by the regional councils whereas MPs of the HoPR are elected directly, in turn, they elect the president for a six-year term and the prime minister for a 5-year term.

The Ethiopian judiciary consists of dual system with two court structures: the federal and state courts. The FDRE Constitution vested federal judicial authority to the Federal Supreme Court which can overturn and review decisions of subordinate federal courts; itself has regular division assigned for fundamental errors of law. In addition, the Supreme Court can perform circuit hearings in established five states at any states of federal levels or "area designated for its jurisdiction" if deemed "necessary for the efficient rendering of justice".[185][186]

The Federal Supreme Proclamation granted three subject matter principles: laws, parties and place to federal court jurisdiction, first "cases arising under the Constitution, federal laws and international treaties", second over "parties specified by federal laws".[187]

On the basis of Article 78 of the 1994 Ethiopian Constitution, the judiciary is completely independent of the executive and the legislature.[188] To ensure this, the President and Vice President of the Supreme Court are appointed by Parliament on the nomination of Prime Minister. Once elected, the executive power has no authority to remove them from office. Other judges are nominated by the Federal Judicial Administration Council (FJAC) on the basis of transparent criteria and the Prime Minister's recommendation for appointment in the HoPR. In all cases, judges cannot be removed from their duty unless they retired, violated disciplinary rules, gross incompatibility, or inefficiency to unfit due to ill health. Contrary, the majority vote of HoPR have the right to sanction removal in federal judiciary level or state council in cases of state judges.[189] In 2015, the realities of this provision were questioned in a report prepared by Freedom House.[190]

Politics[edit]

|  |

| Sahle-Work Zewde President (representative head of state) | Abiy Ahmed Prime Minister (head of government) |

Post-1995, Ethiopia's politics has been liberalized which promotes all-encompassing reforms to the country. Today, its economy is based on mixed, market-oriented principles.[189] Ethiopia has eleven semi-autonomous administrative regions that have the power to raise and spend their own revenues.[citation needed]

The first multiparty election took place in May 1995, which was won by the EPRDF.[191] The president of the transitional government, EPRDF leader Meles Zenawi, became the first Prime Minister of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, and Negasso Gidada was elected its president.[192] Meles' government was consistently re-elected; however, these results were heavily criticized by international observers, and denounced by the opposition as fraudulent.[193]

Meles died on 20 August 2012 in Brussels, where he was being treated for an unspecified illness.[194] Deputy Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn was appointed as a new prime minister until the 2015 elections,[195] and remained so afterwards with his party in control of every parliamentary seat.[196] On 15 February 2018, Hailemariam resigned as Prime Minister, following years of protests and a state of emergency.[197][198][199] Abiy Ahmed became prime minister following Hailemariam's resignation. He made a historic visit to Eritrea in 2018, ending the state of conflict between the two countries,[144] and was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2019.[200]

According to the Democracy Index published by the United Kingdom-based Economist Intelligence Unit in late 2010, Ethiopia was an "authoritarian regime", ranking as the 118th-most democratic out of 167 countries.[201] Ethiopia had dropped 13 places on the list since 2008, and the 2010 report attributed the drop to the government's crackdown on opposition activities, media, and civil society before the 2010 parliamentary election, which the report argued had made Ethiopia a de facto one-party state.[202]

Accompanied by pervasive internal and intercommunal conflicts in the 21st century, the Ethiopian government resorted to authoritarian structure, severing democratic and human rights.[203] Freedom House, who has worked on Ethiopia since 2008, indicates that Ethiopia is "Not Free" state due to very poor fundamental rights (political and civil liberties) recorded in both EPRDF and Prosperity Party regimes.[204][205] Under Abiy Ahmed, Ethiopia is experiencing democratic backsliding since 2019 marked by turbulent period of internal conflict, jailing opposition group members and limit media freedom.[206][207][208]

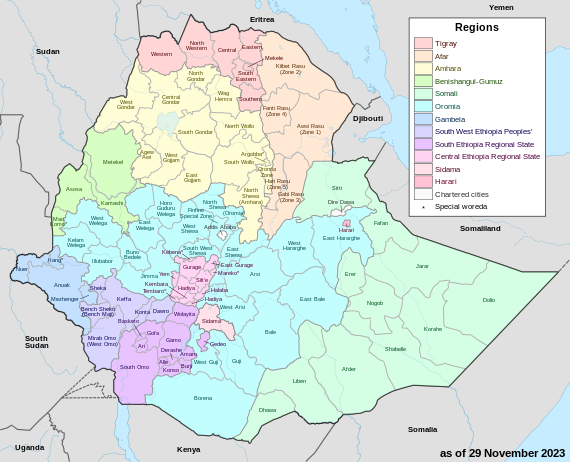

Administrative divisions[edit]

Ethiopia is administratively divided into four levels: regions, zones, woredas (districts) and kebele (wards).[209][210] The country comprises 12 regions and two city administrations under these regions, plenty of zones, woredas and neighbourhood administration: kebeles. The two federal-level city administrations are Addis Ababa and Dire Dawa.[211]

Foreign relations[edit]

Ethiopia was historically a trading nation that exported goods such as gold, ivory, exotic animals, and incense.[212] Modern Ethiopian foreign relations began under Emperor Tewodros II, who during his reign sought to re-establish a cohesive Ethiopian state, but was thwarted by the British expedition of 1868.[213] Since then, the country was seen redundant by world powers until the opening of Suez Canal due to an influence of Mahdist War.[214][clarification needed]

Today, Ethiopia maintains strong relations with China, Israel, Mexico, Turkey and India as well as neighboring countries. Ethiopia is a strategic partner of Global War on Terrorism and African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA).[215] US. Former U.S. President Barack Obama was the first incumbent U.S. president to visit Ethiopia in July 2015; the speech he gave in African Union during this trip focused on combatting Islamic terrorism.[216][217] Emigration from Ethiopia is primarily directed towards Europe, including Italy, the United Kingdom and Sweden, as well as Canada and Australia, while emigration to the Middle East is primarily to Saudi Arabia and Israel. Ethiopia is founding member of the Group of 24 (G-24), the Non-Aligned Movement and the G77. In 1963, the Organization of African Unity, which later renamed itself the African Union, was founded in Addis Ababa, which today hosts the secretariat of the African Union, the African Union Commission. In addition, Ethiopia is also a member of the Pan African Chamber of Commerce and Industry, the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, the African Standby Force[218] and many of global NGOs focused on Africa.

Ethiopia's foreign relations with both Sudan and Egypt are somewhat fraught owing to the effects the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam project, which was escalated in 2020, would have on water rights in the region.[219][220] Despite six upstream countries (Ethiopia, Kenya, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, and Tanzania) signing the Nile Basin Initiative in 2010, Egypt and Sudan rejected a water sharing treaty, citing the reduction of amount of water to the Nile Basin and the challenge it would pose to their historic connection of water rights.[221][222] In 2020, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed warned that "No force can stop Ethiopia from building a dam. If there is need to go to war, we could get millions readied."[223]

Ethiopia is one of the African countries that was a founding member of League of Nations, which served as the predecessor for the United Nations, since 1923. UN taskforces in Ethiopia deal primarily with humanitarian issues and development. Some of its agencies[which?] maintain regional ties with United Nations Economic Commission for Africa and the African Union. The UN prioritizes sustainable development in Ethiopia, including fighting poverty, sustainable economic growth, climate change policy, educational and healthcare provisions, increasing employment, and environmental protection.[224]

Military[edit]

The Ethiopian army's origins and military traditions date back to the earliest history of Ethiopia. Due to Ethiopia's location between the Middle East and Africa, it has long been in the middle of Eastern and Western politics and has been subject to foreign invasions. In 1579, the Ottoman Empire's attempt to expand from a coastal base at Massawa during the Ottoman conquest of Habesh was defeated.[225] The Army of the Ethiopian Empire was also able to defeat the Egyptians in 1876 at Gura, led by Ethiopian Emperor Yohannes IV.[226]

Economy[edit]

Ethiopia registered the fastest economic growth under Meles Zenawi's administration.[227]According to the IMF, Ethiopia was one of the fastest growing economies in the world, registering over 10% economic growth from 2004 through 2009.[228] It was the fastest-growing non-oil-dependent African economy in the years 2007 and 2008.[229] In 2015, the World Bank highlighted that Ethiopia had witnessed rapid economic growth with real domestic product (GDP) growth averaging 10.9% between 2004 and 2014.[230]

In 2008 and 2011, Ethiopia's growth performance and considerable development gains were challenged by high inflation and a difficult balance of payments situation. Inflation surged to 40% in August 2011 because of loose monetary policy, large civil service wage increase in early 2011, and high food prices.[231]

In spite of fast growth in recent years, GDP per capita is one of the lowest in the world, and the economy faces a number of serious structural problems. However, with a focused investment in public infrastructure and industrial parks, Ethiopia's economy is addressing its structural problems to become a hub for light manufacturing in Africa.[232] In 2019 a law was passed allowing expatriate Ethiopians to invest in Ethiopia's financial service industry.[233]

The Ethiopian constitution specifies that rights to own land belong only to "the state and the people", but citizens may lease land for up to 99 years, but are unable to mortgage or sell. Renting out land for a maximum of twenty years is allowed and this is expected to ensure that land goes to the most productive user. Land distribution and administration is considered an area where corruption is institutionalized, and facilitation payments as well as bribes are often demanded when dealing with land-related issues.[234] As there is no land ownership, infrastructural projects are most often simply done without asking the land users, which then end up being displaced and without a home or land. A lot of anger and distrust sometimes results in public protests. In addition, agricultural productivity remains low, and frequent droughts still beset the country, also leading to internal displacement.[235]

Energy and hydropower[edit]

Ethiopia has 14 major rivers flowing from its highlands, including the Nile. It has the largest water reserves in Africa. As of 2012[update], hydroelectric plants represented around 88.2% of the total installed electricity generating capacity.

The remaining electrical power was generated from fossil fuels (8.3%) and renewable sources (3.6%).

The electrification rate for the total population in 2016 was 42%, with 85% coverage in urban areas and 26% coverage in rural areas. As of 2016[update], total electricity production was 11.15 TW⋅h and consumption was 9.062 TW⋅h. There were 0.166 TW⋅h of electricity exported, 0 kW⋅h imported, and 2.784 GW of installed generating capacity.[17]Ethiopia delivers roughly 81% of water volume to the Nile through the river basins of the Blue Nile, Sobat River and Atbara. In 1959, Egypt and Sudan signed a bilateral treaty, the 1959 Nile Waters Agreement, which gave both countries exclusive maritime rights over the Nile waters. Ever since, Egypt has discouraged almost all projects in Ethiopia that sought to use the local Nile tributaries. This had the effect of discouraging external financing of hydropower and irrigation projects in western Ethiopia, thereby impeding water resource-based economic development projects. However, Ethiopia is in the process of constructing a large 6,450 MW hydroelectric dam on the Blue Nile river. When completed, this Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam is slated to be the largest hydroelectric power station in Africa.[236] The Gibe III hydroelectric project is so far the largest in the country with an installed capacity of 1,870 MW. For the year 2017–18 (2010 E.C) this hydroelectric dam generated 4,900 GW⋅h.[237]

Agriculture[edit]

Agriculture constitutes around 85% of the labour force. However, the service sector represents the largest portion of the GDP.[17] Many other economic activities depend on agriculture, including marketing, processing, and export of agricultural products. Production is overwhelmingly by small-scale farmers and enterprises, and a large part of commodity exports are provided by the small agricultural cash-crop sector. Principal crops include coffee, legumes, oilseeds, cereals, potatoes, sugarcane, and vegetables. Ethiopia is also a Vavilov centre of diversity for domesticated crops, including enset,[238] coffee Okra and teff.

Exports are almost entirely agricultural commodities (with the exception of gold exports), and coffee is the largest foreign exchange earner. Ethiopia is Africa's second biggest maize producer.[239] According to UN estimations, the per capita GDP of Ethiopia has reached $357 as of 2011[update].[240]

Exports[edit]

Ethiopia is often considered as the birthplace of coffee since cultivation began in the 9th century.[244] Exports from Ethiopia in the 2009–2010 financial year totalled US$1.4 billion.[245] Ethiopia produces more coffee than any other nation on the continent.[246] "Coffee provides a livelihood for close to 15 million Ethiopians, 16% of the population. Farmers in the eastern part of the country, where a warming climate is already impacting production, have struggled in recent years, and many are currently reporting largely failed harvests as a result of a prolonged drought".[247]

Ethiopia also has the fifth largest inventory of cattle.[248] Other main export commodities are khat, gold, leather products, and oilseeds. Recent development of the floriculture sector means Ethiopia is poised to become one of the top flower and plant exporters in the world.[249]

Cross-border trade by pastoralists is often informal and beyond state control and regulation. In East Africa, over 95% of cross-border trade is through unofficial channels. The unofficial trade of live cattle, camels, sheep, and goats from Ethiopia sold to Somalia, Djibouti, and Kenya generates an estimated total value of US$250–300 million annually (100 times more than the official figure).[250]

This trade helps lower food prices, increase food security, relieve border tensions, and promote regional integration.[250] However, the unregulated and undocumented nature of this trade runs risks, such as allowing disease to spread more easily across national borders. Furthermore, the government of Ethiopia is purportedly unhappy with lost tax revenue and foreign exchange revenues.[250] Recent initiatives have sought to document and regulate this trade.[250]

With the private sector growing slowly, designer leather products like bags are becoming a big export business, with Taytu becoming the first luxury designer label in the country.[251] Additional small-scale export products include cereals, pulses, cotton, sugarcane, potatoes, and hides. With the construction of various new dams and growing hydroelectric power projects around the country, Ethiopia also plans to export electric power to its neighbours.[252][253]

Most regard Ethiopia's large water resources and potential as its "white oil" and its coffee resources as "black gold".[254][255]

Transport[edit]

Two trans-African automobile routes pass through Ethiopia: the Cairo-Cape Town Highway and the N'Djamena-Djibouti Highway. Ethiopia has 926 km of electrified 1,435 mm (4 ft 8+1⁄2 in) standard gauge railways, 656 km for the Addis Ababa–Djibouti Railway between Addis Ababa and the Port of Djibouti (via Awash)[256] and 270 km for the Awash–Hara Gebeya Railway between Addis Ababa and the twin cities of Dessie/Kombolcha.[257]

Ethiopia had 58 airports as of 2012[update],[17] and 61 as of 2016[update].[258] Among these, the Bole International Airport in Addis Ababa and the Aba Tenna Dejazmach Yilma International Airport in Dire Dawa accommodate international flights.

Science and technology[edit]

Science and technology in Ethiopia emerging as progressive due to lack of organized institutions. Manufacturing and service providers often place themselves in competitive programming in order to advance innovative and technological solutions through in-house arenas.[clarification needed] The Ethiopian Space Science and Technology is responsible for conducting multifaceted tasks regarding space and technology. In addition, Ethiopia also launched 70 kg ET-RSS1 multi-spectral remote sensing satellite in December 2019. The President Sahle-Work Zewde told prior in October 2019 that "the satellite will provide all the necessary data on changes in climate and weather-related phenomena that would be used for the country's key targets in agriculture, forestry as well as natural resources protection initiatives." By January 2020, satellite manufacturing, assembling, integrating and testing began. This would also incremented facility built by French company funded by European Investment Bank (EIB). The main observatory Entoto Observatory and Space Science Research Center (EORC) allocated space programmes. The Ethiopian Biotechnology Institute is a part of Scientific Research & Development Services Industry, responsible for environmental and climate conservation.[261] Numerous profound scientists have contributed degree of honours and reputations. Some are Kitaw Ejigu, Mulugeta Bekele, Aklilu Lemma, Gebisa Ejeta and Melaku Worede. Computer scientist Timnit Gebru, named one of Time's most influential people in 2022, was born in Ethiopia.[262]

Ethiopia is known for use of traditional medicine since millennia. The first epidemic occurred in Ethiopia was in 849, causing the Aksumite Emperor Abba Yohannes evicted from place due to "God's punishment for misdeeds". The first traditional medicine was claimed to be derived from this catastrophe, but the exact source is debated. Though differ from ethnic groups, traditional medicine often implements herbs, spiritual healing, bone-setting and minor surgical procedures in treating disease.[263]

Ethiopia was ranked 125th in the Global Innovation Index in 2023.[264]

Demographics[edit]

Ethiopia is the most populous landlocked country in the world.[265] Its total population has grown from 38.1 million in 1983 to 109.5 million in 2018.[266] According to UN estimations in 2013, life expectancy had improved substantially over time, with male life expectancy reported to be 56 years and for women 60 years.[240]

Ethiopia's population is highly diverse, containing over 80 different ethnic groups, the four largest of which are the Oromo, Amhara, Somali and Tigrayans. According to the Ethiopian national census of 2007, the Oromo are the largest ethnic group in Ethiopia, at 34.4% of the nation's population. The Amhara represent 27.0% of the country's inhabitants, while Somalis and Tigrayans represent 6.2% and 6.1% of the population respectively.[6]

Afroasiatic-speaking communities make up the majority of the population. Among these, Semitic speakers often collectively refer to themselves as the Habesha people. The Arabic form of this term (al-Ḥabasha) is the etymological basis of "Abyssinia", the former name of Ethiopia in English and other European languages.[267]

In 2009, Ethiopia hosted a population of refugees and asylum seekers numbering approximately 135,200. The majority of this population came from Somalia (approximately 64,300 persons), Eritrea (41,700) and Sudan (25,900). The Ethiopian government required nearly all refugees to live in refugee camps.[268]

Urbanization[edit]

Population growth, migration, and urbanization are all straining both governments' and ecosystems' capacity to provide people with basic services.[269] Urbanization has steadily been increasing in Ethiopia, with two periods of significantly rapid growth. First, in 1936–1941 during the Italian occupation under Mussolini's fascist government, and then from 1967 to 1975 when the populations of urban areas tripled.[270]

In 1936, Italy annexed Ethiopia, building infrastructure to connect major cities, and a dam providing power and water.[271] This, along with the influx of Italians and labourers, was the major cause of rapid growth during this period. The second period of growth was from 1967 to 1975, when rural populations migrated to towns seeking work and better living conditions.[270]

This pattern slowed due to the 1975 Land Reform program instituted by the government, which provided incentives for people to stay in rural areas. As people moved from rural areas to the cities, there were fewer people to grow food for the population. The Land Reform Act was meant to increase agriculture since food production was not keeping up with population growth over the period of 1970–1983. This program encouraged the formation of peasant associations, large villages based on agriculture. The legislation did lead to an increase in food production, although there is debate over the cause; it may be related to weather conditions more than the reform.[272] Urban populations have continued to grow with an 8.1% increase from 1975 to 2000.[273]

| Rank | Name | Region | Municipal pop. | Rank | Name | Region | Municipal pop. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Addis Ababa  Gondar | 1 | Addis Ababa | Addis Ababa | 3,352,000 | 11 | Shashamane | Oromia | 154,587 |  Mek'ele  Adama |

| 2 | Gondar | Amhara | 341,991 | 12 | Bishoftu | Oromia | 153,847 | ||

| 3 | Mek'ele | Tigray | 340,858 | 13 | Sodo | SNNPR | 253,322 | ||

| 4 | Adama | Oromia | 338,940 | 14 | Arba Minch | SNNPR | 151,013 | ||

| 5 | Hawassa | SNNPR | 318,618 | 15 | Hosaena | SNNPR | 141,352 | ||

| 6 | Bahir Dar | Amhara | 297,794 | 16 | Harar | Harari | 133,000 | ||

| 7 | Dire Dawa | Dire Dawa | 285,000 | 17 | Dila | SNNPR | 119,276 | ||

| 8 | Dessie | Amhara | 198,428 | 18 | Nekemte | Oromia | 115,741 | ||

| 9 | Jimma | Oromia | 186,148 | 19 | Debre Birhan | Amhara | 107,827 | ||

| 10 | Jijiga | Somali | 164,321 | 20 | Asella | Oromia | 103,522 | ||

As of at least 2024, Ethiopia is one of the most rapidly urbanizing countries in the world, although its population is still largely urban.[275]

Rural and urban life[edit]

Migration to urban areas is usually motivated by the hope of better lives. In peasant associations, daily life is a struggle to survive. About 16% of the population in Ethiopia lives on less than one dollar per day (2008). Only 65% of rural households in Ethiopia consume the World Health Organization's (WHO's) minimum standard of food per day (2,200 kilocalories), with 42% of children under five years old being underweight.[276]

Most poor families (75%) share their sleeping quarters with livestock, and 40% of children sleep on the floor, where nighttime temperatures average 5 degrees Celsius in the cold season.[276] The average family size is six or seven, living in a 30 square metre mud and thatch hut, with less than two hectares of land to cultivate.[276]

The peasant associations face a cycle of poverty. Since the landholdings are so small, farmers cannot allow the land to lie fallow, which reduces soil fertility.[276] This land degradation reduces the production of fodder for livestock, which causes low milk yields.[276] Since the community burns livestock manure as fuel, rather than plowing the nutrients back into the land, the crop production is reduced.[276] The low productivity of agriculture leads to inadequate incomes for farmers, hunger, malnutrition and disease. These unhealthy farmers have difficulty working the land and the productivity drops further.[276]

Although conditions are drastically better in cities, all of Ethiopia suffers from poverty and poor sanitation. However, poverty in Ethiopia fell from 44% to 29.6% during 2000–2011, according to the World Bank.[277] In the capital city of Addis Ababa, 55% of the population used to live in slums.[271] Now, however, a construction boom in both the private and the public sector has led to a dramatic improvement in living standards in major cities, particularly in Addis Ababa. Notably, government-built condominium housing complexes have sprung up throughout the city, benefiting close to 600,000 individuals.[278] Sanitation is the most pressing need in the city, with most of the population lacking access to waste treatment facilities. This contributes to the spread of illness through unhealthy water.[271]

Despite the living conditions in the cities, the people of Addis Ababa are much better off than people living in the peasant associations owing to their educational opportunities. Unlike rural children, 69% of urban children are enrolled in primary school, and 35% of those are eligible to attend secondary school.[clarification needed][271] Addis Ababa has its own university as well as many other secondary schools. The literacy rate is 82%.[271]

Many NGOs (Non-Governmental Organizations) are working to solve this problem; however, most are far apart, uncoordinated, and working in isolation.[273] The Sub-Saharan Africa NGO Consortium is attempting to coordinate efforts.[273]

Languages[edit]

According to Glottolog, there are 109 languages spoken in Ethiopia, while Ethnologue lists 90 individual languages spoken in the country.[279][280] Most people in the country speak Afroasiatic languages of the Cushitic or Semitic branches. The former includes the Oromo language, spoken by the Oromo, and Somali, spoken by the Somalis; the latter includes Amharic, spoken by the Amhara, and Tigrinya, spoken by the Tigrayans. Together, these four groups make up about three-quarters of Ethiopia's population. Other Afroasiatic languages with a significant number of speakers include the Cushitic Sidamo, Afar, Hadiyya and Agaw languages, as well as the Semitic Gurage languages, Harari, Silt'e, and Argobba languages.[6] Arabic, which also belongs to the Afroasiatic family, is likewise spoken in some areas.[281]

English is the most widely spoken foreign language, the medium of instruction in secondary schools and all tertiary education; federal laws are also published in British English in the Federal Negarit Gazeta including the 1995 constitution.[282]

Amharic was the language of primary school instruction, but has been replaced in many areas by regional languages such as Oromo, Somali or Tigrinya.[283] All languages enjoy equal state recognition in the 1995 Constitution of Ethiopia.[140]

Script[edit]

Ethiopia's principal orthography is the Ge'ez script. Employed as an abugida for several of the country's languages, it first came into usage in the 6th and 5th centuries BC as an abjad to transcribe the Semitic Ge'ez language.[284] Ge'ez now serves as the liturgical language of both the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo and Eritrean Orthodox Tewahedo Churches. During the 1980s, the Ethiopic character set was computerized. It is today part of the Unicode standard as Ethiopic, Ethiopic Extended, Ethiopic Supplement and Ethiopic Extended-A.

Other writing systems have also been used over the years by different Ethiopian communities. The latter include Bakri Sapalo's script for Oromo.[285]

Religion[edit]

According to the 2007 National Census, Christians make up 62.8% of the country's population, Muslims 33.9%, practitioners of traditional faiths 2.6%, and other religions 0.6%.[6] The ratio of the Christian to Muslim population has largely remained stable when compared to previous censuses conducted decades ago.[287] Sunnis form the majority of Muslims with non-denominational Muslims being the second largest group of Muslims, and the Shia are a minority. Sunnis are largely Shafi'is or Salafis, and there are also many Sufi Muslims there.[288]

Ethiopia has close historical ties with all three of the world's major Abrahamic religions. In the 4th century, the Ethiopian empire was one of the first in the world to officially adopt Christianity as the state religion. As a result of the resolutions of the Council of Chalcedon, in 451 the Miaphysites, which included the vast majority of Christians in Egypt and Ethiopia, were accused of monophysitism and designated as heretics under the common name of Coptic Christianity (see Oriental Orthodoxy).[289]

The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church is part of Oriental Orthodoxy. It is by far the largest Christian denomination, although a number of P'ent'ay (Protestant) churches have recently gained ground. Since 1930, a relatively small Ethiopian Catholic Church has existed in full communion with Rome, with adherents making up less than 1% of the total population.[287][290]

Islam in Ethiopia dates back to the founding of the religion in 622 when a group of Muslims were counselled by Muhammad to escape persecution in Mecca. The disciples subsequently migrated to Abyssinia via modern-day Eritrea, which was at the time ruled by Ashama ibn-Abjar, a pious Christian emperor.[291]

Health[edit]

Only a minority of Ethiopians are born in hospitals, while most are born in rural households. Those who are expected to give birth at home have elderly women serve as midwives who assist with the delivery.[292] The "WHO estimates that a majority of maternal fatalities and disabilities could be prevented if deliveries were to take place at well-equipped health centres, with adequately trained staff".[293] Birth rates, infant mortality rates, and death rates are lower in cities than in rural areas due to better access to education, medicines, and hospitals.[271] Life expectancy is better in cities compared to rural areas, but there have been significant improvements witnessed throughout the country as of 2016, the average Ethiopian living to be 62.2 years old, according to a UNDP report.[294] Despite sanitation being a problem, use of improved water sources is also on the rise; 81% in cities compared to 11% in rural areas.[273]

Ethiopia's main health problems are said to be communicable (contagious) diseases worsened by poor sanitation and malnutrition. Over 58 million people (nearly half the population) do not have access to clean water as of 2023.[295] These problems are exacerbated by the shortage of trained doctors and nurses and health facilities.[296] The World Health Organization's 2006 World Health Report gives a figure of 1,936 physicians (for 2003), which comes to about 2.6 per 100,000.[297]

The National Mental Health Strategy, published in 2012, introduced the development of policy designed to improve mental health care in Ethiopia. This strategy mandated that mental health be integrated into the primary health care system.[298] However, the success of the National Mental Health Strategy has been limited. For example, the burden of depression is estimated to have increased 34.2% from 2007 to 2017.[299] Furthermore, the prevalence of stigmatizing attitudes, inadequate leadership and co-ordination of efforts, as well as a lack of mental health awareness in the general population, all remain as obstacles to successful mental health care.[300]

Education[edit]

The current system follows school expansion schemes which are very similar to the system in the rural areas during the 1980s, with an addition of deeper regionalization, providing rural education in students' own languages starting at the elementary level, and with more budgetary financing allocated to the education sector. Public education is free at primary levels and usually offers between age 7 and 12. The sequence of general education in Ethiopia is six years of primary school, then four years of lower secondary school followed by two years of higher secondary school.[301]

The Ethiopian education is governed by the Ministry of Education and its cycle consists of a 4+4+2+2 system; elementary education consists of eight years, divided into two cycles of four years, and four years of secondary education, divided into two stages of two years.[302] National exams are conducted by the National Education Assessment and Examination Agency (NEAEA). Since 2018, there are two national exams: the Ethiopian General Secondary Education Certificate Examination (EGSECE), also known as Grade 10 national exam and Grade 12 national exam.[303]

As of 2022, there are 83 universities, 42 public universities, and more than 35 higher education institutions. Foreign students constitute 16,305 in higher education level. The overall number of tertiary students in both public and private institutions exploded by more than 2,000 percent, from 34,000 in 1991 to 757,000 in 2014, per UIS data.[citation needed] Access to education in Ethiopia has improved significantly. Approximately three million people were in primary school in 1994–95 but by 2008–09, primary enrolment had risen to 15.5 million – an increase of over 500%.[304] In 2013–14, Ethiopia had witnessed a significant boost in gross enrolment across all regions.[305] The national GER was 104.8% for boys, 97.8% for girls and 101.3% across both sexes.[306]

The literacy rate has increased in recent years: according to the 1994 census, the literacy rate in Ethiopia was 23.4%.[280] In 2007 it was estimated to be 39% (male 49.1% and female 28.9%).[307] A report by UNDP in 2011 showed that the literacy rate in Ethiopia was 46.7%. The same report also indicated that the female literacy rate had increased from 27 to 39 per cent from 2004 to 2011, and the male literacy rate had increased from 49 to 59 per cent over the same period for persons 10 years and older.[308] By 2015, the literacy rate had further increased, to 49.1% (57.2% male and 41.1% female).[309]

Culture[edit]

Ethiopia's culture heavily influenced by the local population, an interaction of Semitic, Cushitic and less populous Nilo-Saharan speaking people, which evolved from first millennium BC. Semitic Tigrayans and Amharas, who dominated the politics in the past, distinguished from other population by hierarchical structure and agrarian life derived partly from South Arabia as a result of back migration, while the southern Cushitic (Oromo and Somali) are strong adherents to egalitarianism and pastoral life. Others including Kaffa, Sidamo, and Afar tradition derived from the latter people.[310]

Arts[edit]

Arts of Ethiopia were largely influenced by Christian iconography throughout much of its history. This consisted of illuminated manuscripts, painting, crosses, icons and other metalwork such as crowns. Most historical arts were commissioned by the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church, the state religion for a millennium. The earlier Aksumite period arts were stone carvings as evidenced in their stelae, though there is no surviving Christian art from this era. As Christianity was introduced, its iconography was partly influenced by Byzantine art. Most remaining arts beyond the early modern period were ruined as a result of invasion of the Adal Sultanate in the Ethiopian Highlands, but were revived by Catholic emissaries. The Western intervention in Ethiopian art began in the 20th century, with also maintaining traditional Ethiopian character.[citation needed]

Architecture[edit]

The "Bete Medhane Alem" or "House of our Saviour" is one of the 12 churches in Lalibela built under Emperor Lalibela I. Perhaps the most impressive[opinion] architecture in antiquity was founded during the Dʿmt period. Ashlar masonry was an archetype of South Arabian architecture with most architectural structure similarity.[311]

The Aksumite continued to flourish its architecture around the 4th century CE. Aksumite stelae commonly used single block and rocks. The Tomb of the False Door built for Aksumite emperors used monolithic style.[312] The Lalibela civilization was largely of Aksumite influence, but the layer of stones or wood is quite different for some dwellings.[313]

In the Gondarine period, the architecture of Ethiopia was infused by Baroque, Arab, Turkish and Gujarati Indian styles independently taught by Portuguese emissaries in the 16th and 17th centuries. Examples include the imperial fortress Fasil Ghebbi, which is influenced by either of these styles. The medieval architecture also forborne the later 19th- and 20th-century era of designations.[314]

Literature[edit]

Ethiopian literature traces back to the Aksumite period in the 4th century, mostly religious motifs. In royal inscription, it employed both Ge'ez and Greek language, but the latter was discontinued in 350. Unlike most Sub-Saharan African countries, Ethiopia has ancient distinct language, the Ge'ez, which dominated political and educational aspects. In spite of the current political instability in the country endangering cultural heritage of these works, preservation has improved in recent years.[315]

The Ethiopian literary works mostly consisted of handwritten codex (branna, or ብራና in Amharic). It is prepared by gathering parchment leaves and sewing to stick together. The codex size varies considerably depending on volumes and preparation. For example, pocket size codex lengthens 45 cm, which is heavier in weight. Historians speculated that archaic codex existed in Ethiopia. Today manuscripts resembling primitive codex are still evident for existence where parchment leaves are convenient for writing.[315]

Another notable writing book is protective (or magic) scroll, serving as written amulet. Some of these were intended for magical purpose, for example ketab is used for magical defence. Scrolls were typically produced by debtera, non-ordained clergy expertise on exorcism and healings. About 30 cm scroll is portable whereas 2 cm is often unrolled and hanged to the walls of houses. Scrolls emulating original medium of Ethiopia literature is highly disputed, where there is overwhelming evidence that Ge'ez language books were written in codex. In lesser, Ethiopia used accordion books (called sensul) which were dated to late 15th or 16th century, made up of folded parchment paper, with or without cover. Those books usually contain pictorial representation of life and death of religious figures, or significant texts have also juxtaposed.[315]

Poetry[edit]

Ethiopia is highly popularized in poetry. Most poets recount past events, social unrests, poverty and famine. Qene is the most used element of Ethiopian poetry – regarded as a form of Amharic poetry, though the term generally refers to any poems. True qene requires advanced ingenious mindset. By providing two metaphorical words, i.e. one with obvious clues and the other is too convoluted conundrum, one must answer parallel meanings. Thus, this is called sem ena work (gold and wax).[316] The most notable poets are Tsegaye Gebre-Medhin, Kebede Michael and Mengistu Lemma.

Philosophy[edit]

Ethiopian philosophy has been superlatively prolific since ancient times in Africa, though offset of Greek and Patristic philosophy. The best known philosophical revival was in the early modern period figures such as Zera Yacob (1599–1692) and his student Walda Heywat, who wrote Hatata (Inquiry) in 1667 as an argument for the existence of God.

Music[edit]

The music of Ethiopia is extremely diverse, with each of the country's 80 ethnic groups being associated with unique sounds. Ethiopian music uses a distinct modal system that is pentatonic, with characteristically long intervals between some notes. As with many other aspects of Ethiopian culture and tradition, tastes in music and lyrics are strongly linked with those in neighbouring Eritrea, Somalia, Djibouti, and Sudan.[317][318] Traditional singing in Ethiopia presents diverse styles of polyphony (heterophony, drone, imitation, and counterpoint). Traditionally, lyricism in Ethiopian song writing is strongly associated with views of patriotism or national pride, romance, friendship, and a unique type of memoire known as tizita.

Saint Yared, a 6th-century Aksumite composer, is widely regarded as the forerunner of traditional music of Eritrea and Ethiopia, creating liturgical music of the Ethiopian and Eritrean Orthodox Tewahedo Church.[319]

Modern music is traced back to the reign of Emperor Haile Selassie, where 40 Armenian orphans called Arba Lijoch arrived from Jerusalem to Addis Ababa. By 1924, the band was almost established as orchestral; but after World War II, several similar bands emerged such as Imperial Bodyguard Band, Army Band, and Police Band.[320]