George Albert Smith (filmmaker)

George Albert Smith | |

|---|---|

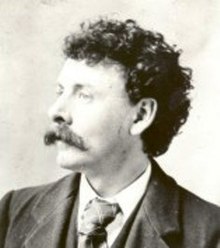

George Albert Smith in 1902 | |

| Born | 4 January 1864 London, England |

| Died | 17 May 1959 (aged 95) |

| Occupation(s) | Film maker, inventor |

| Spouse | Laura Bayley |

George Albert Smith (4 January 1864 – 17 May 1959) was an English stage hypnotist, psychic, magic lantern lecturer, Fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society, inventor and a key member of the loose association of early film pioneers dubbed the Brighton School by French film historian Georges Sadoul. He is best known for his controversial work with Edmund Gurney at the Society for Psychical Research, his short films from 1897 to 1903, which pioneered film editing and close-ups, and his development of the first successful colour film process, Kinemacolor.[1][2]

Biography

[edit]Birth and early life

[edit]Smith was born in Cripplegate, London in 1864. His father Charles Smith was a ticket-writer and artist.[3] He moved with his family to Brighton, where his mother ran a boarding house on Grand Parade, following the death of his father.

It was in Brighton in the early 1880s that Smith first came to public attention touring the city's performance halls as a stage hypnotist. In 1882 he teamed up with Douglas Blackburn in an act at the Brighton Aquarium involving muscle reading, in which the blindfolded performer identifies objects selected by the audience, and second sight, in which the blindfolded performer finds objects hidden by his assistant somewhere in the theatre.[4]

The Society for Psychical Research (SPR) accepted Smith's claims that the act was genuine and after becoming a member of the society he was appointed private secretary to the Honorary Secretary Edmund Gurney from 1883 to 1888. In 1887, Gurney carried out a number of "hypnotic experiments" in Brighton, with Smith as his "hypnotiser", which in their day made Gurney an impressive figure to the British public.

Since then it has been heavily studied and critiqued by Trevor H. Hall in his study The Strange Case of Edmund Gurney. Hall concluded that Smith (using his stage abilities) faked the results that Gurney trusted in his research papers, and this may have led to Gurney's mysterious death from a narcotic overdose in June 1888. Following Gurney's death, his successors, F. W. H. Myers and Frank Podmore, continued to employ Smith as their private secretary. In 1889, he co-authored (with Henry Sidgwick and Eleanor Mildred Sidgwick) the paper, Experiments in Thought Transference, for the society's journal.[5]

Blackburn publicly admitted fraud in 1908 and again in 1911,[6] although Smith consistently denied it.[7][8]

At St. Ann's Well Gardens

[edit]

In 1892, after leaving the SPR, he acquired the lease of the St. Ann's Well Gardens in Hove from the estate of financier and philanthropist Sir Isaac Lyon Goldsmid, which he cultivated into a popular pleasure garden, where from 1894 he started staging public exhibitions of hot air ballooning, parachute jumps, a monkey house, a fortune teller, a hermit living in a cave and magic lantern shows of a series of dissolving views.[9] Smith also began to present these dioramic lectures at the Brighton Aquarium, where he had first performed with Douglas Blackburn in 1882. Smith's skilful manipulation of the lantern, cutting between lenses (from slide to slide) to show changes in time, perspective and location necessary for story telling, would allow him to develop many of the skills he would later put to use as a pioneering film maker developing the grammar of film editing.[10]

Smith had attended the Lumière programme in Leicester Square in March 1896 and spurred on by the films of Robert Paul, which played in Brighton for that summer season, he and local chemist James Williamson acquired a prototype cine cameras from local engineer Alfred Darling, who had begun to manufacture film equipment after carrying out repairs for Brighton-based film pioneer Esmé Collings. In 1897, with the technical assistance of Darling and chemicals purchased from Williamson, Smith turned the pump house into a film factory for developing and printing and developed into a successful commercial film processor as well as patenting a camera and projector system of his own. Both he and his neighbour Williamson would go on to become pioneering film makers in their own right creating numerous historic minute-long films.[1][2]

On 29 March 1897, Smith added animated photographs to the end of his twice-daily programme of projected entertainment at the Brighton Aquarium, as an outlet for his burgeoning film production. Many of Smith's early films, including The Miller and the Sweep and Old Man Drinking a Glass of Beer (both filmed in 1897) were comedies thanks to the influence of his wife, Laura Bayley, who had previously acted in pantomime and comic revue. However Smith also corresponded with special effects pioneer Georges Méliès whose influence can be seen in The X-Rays and The Haunted Castle (both 1897) the later of which, along with The Corsican Brothers, Photographing a Ghost and, perhaps his most accomplished work from this time, Santa Claus (all 1898), include special effects created using a process of double-exposure patented by Smith. Many of Smith's films were acquired for distribution by Charles Urban for the Warwick Trading Company and the two began a long business relationship with a joint show of Smith and Méliès' films at the Alhambra Theatre, Brighton in late 1898 and early 1899.

In 1899 Smith, with the financial assistance of Urban, constructed a glass house film studio at St. Ann's Well Gardens, ushering in a highly creative period for him as a film maker. That year he shot the single scene The Kiss in the Tunnel (1899) which was then seamlessly edited into Cecil Hepworth's View From an Engine Front - Train Leaving Tunnel (1899) to enliven the staid phantom ride genre and demonstrate the possibilities of creative editing. The following year he experimented with reversing in The House That Jack Built (1900), developed dream-time and the dissolve effect in Let Me Dream Again (1900) and pioneered the use of the close-up with Grandma's Reading Glass, As Seen Through a Telescope and Spiders on a Web (all 1900). Film historian Frank Gray describes this experimental period, from 1897 to 1900, as Smith's laboratory years.[10]

In 1902 Smith collaborated with old friend Georges Méliès at the Star Films studio in Montreil, Paris, on a pre-enactment of the Coronation of King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra commissioned by Charles Urban of the Warwick Trading Company after rival company Mutoscope and Biograph acquired the rights to film the actual event. In 1903 Charles Urban left the Warwick Trading Company to form the Charles Urban Trading Company taking the rights to Smith's films with him, at what marked the end of his most active period as a film-maker.

At Laboratory Lodge

[edit]In 1904, A. H. Tee took over the lease on St Ann's Well Gardens, and Smith moved to a new home in Southwick, Sussex, dubbed Laboratory Lodge, where with finance from Charles Urban, he went on to develop the Lee-Turner Process, which had been acquired by Urban following the death of Edward Raymond Turner in 1903, into the first successful colour film process, Kinemacolor.[11]

Smith was granted a patent for the new process,[12] which abandoned the three-colour approach of Edward Turner in favour of a two-colour (red-green) The process was first demonstrated on 1 May 1908, followed by further demonstrations in 1908 and public demonstration from early 1909 as far afield as Paris and New York, for which Smith was awarded a silver medal by the Royal Society of Arts.

In 1909 Urban founded the Natural Color Kinematograph Company, intended to commercially exploit the Kinemacolor process. Urban’s future wife, Ada Jones, purchased the Kinemacolor patent from Smith. This enabled Urban to sell Kinemacolor licenses all around the world. Smith felt he was cheated into selling his invention too cheaply, and Urban believed that Smith was selling secrets to rival inventors. However, Smith remained an employee of the Natural Color Kinematograph Company and testified on its behalf during the 1914 lawsuit by rival inventor William Friese-Greene, which challenged Smith's Kinemacolor patent. Smith's patent for the Kinemacolor process was revoked in 1915, after which it faded out of public view.[13][14]

Later life and death

[edit]In the late 1940s he was rediscovered by the British film community, being made a Fellow of the British Film Academy in 1955.[11] Smith died in Brighton on 17 May 1959.[15] Hove Museum has a permanent display on Smith and Williamson.

Selected filmography

[edit]- The Haunted Castle (1897)

- Making Sausages (1897)

- Old Man Drinking a Glass of Beer (1897)

- The X-Rays (1897)

- The Miller and the Sweep (1898)

- Photographing a Ghost (1898)

- Santa Claus (1898)

- The Kiss in the Tunnel (1899)

- As Seen Through a Telescope (1900)

- Grandma's Reading Glass (1900)

- Grandma Threading her Needle (1900)

- A Quick Shave and Brush-up (1900)

- Spiders on a Web (1900)

- The Old Maid's Valentine (1900)

- The House That Jack Built (1900)

- Let Me Dream Again (1900)

- The Inexhaustible Cab (1901)

- The Death of Poor Joe (1901)

- Mary Jane's Mishap (1903)

- The Sick Kitten (1903)

- Tartans of Scottish Clans (1906)

- Two Clowns (1906)

- Woman Draped in Patterned Handkerchiefs (1908)

- A Visit to the Seaside (1908)

References

[edit]- ^ a b Gray, Frank. "Smith, G.A. (1864-1959)". BFI Screenonlinee. Retrieved 24 April 2011.

- ^ a b Gray, Frank. "George Albert Smith". Who's Who in Victorian Cinema. Retrieved 24 April 2011.

- ^ Hall (1964), p. 92.

- ^ Hall (1964), pp. 92–94.

- ^ Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research, volume 6 (1889-90), pp. 128–70.

- ^ The Daily News, 5 September 1911, cited in Hall (1964), p. 123.

- ^ Oppenheim, Janet (1988). The Other World: Spiritualism and Psychical Research in England, 1850-1914. Cambridge University Press. p. 144. ISBN 0-521-34767-X.

- ^ Hall (1964), pp. 120–123.

- ^ Hall (1964), pp. 169–72.

- ^ a b Gray, Frank (2009), "The Kiss in the Tunnel (1899), G.A. Smith and the Rise of the Edited Film in England", in Grieveson, Lee; Kramer, Peter (eds.), The Silent Cinema Reader, Routledge (published 2004), ISBN 978-0415252843

- ^ a b Hall (1964), p. 172.

- ^ Smith (25 July 1907). Improvements in, and relating to, Kinematograph Apparatus for the Production of Coloured Pictures - British patent 26,607 (PDF).

- ^ McKernan, Luke (2018). Charles Urban: Pioneering the Non-Fiction Film in Britain and America, 1897-1925. University of Exeter Press. ISBN 978-0859892964.

- ^ McKernan, Luke (1999). A Yank in Britain: The Lost Memoirs of Charles Urban. Projection Box. ISBN 9780952394129.

- ^ Hall (1964), p. 173.

Bibliography

[edit]- Hall, Trevor H. (1964). The Strange Case of Edmund Gurney. Gerald Duckworth.