Old East Slavic

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2020) |

| Old East Slavic | |

|---|---|

Sheet from the Radziwiłł Chronicle | |

| Region | Eastern Europe |

| Era | 7th or 8th century to the 13th or 14th century[1][2] developed into Russian and Ruthenian |

Indo-European

| |

| Early Cyrillic alphabet | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | orv |

orv | |

| Glottolog | oldr1238 |

Old East Slavic[a] (traditionally also Old Russian) was a language (or a group of dialects) used by the East Slavs from the 7th or 8th century to the 13th or 14th century,[4] until it diverged into the Russian and Ruthenian languages.[5] Ruthenian eventually evolved into the Belarusian, Rusyn, and Ukrainian languages.[6]

Terminology

[edit]The term Old East Slavic is used in reference to the modern family of East Slavic languages. However, it is not universally applied.[7] The language is also traditionally known as Old Russian;[8][9][10][11] however, the term may be viewed as anachronistic, because the initial stages of the language which it denotes predate the dialectal divisions marking the nascent distinction between modern East Slavic languages,[12] therefore a number of authors have proposed using Old East Slavic (or Common East Slavic) as a more appropriate term.[13][14][15] Old Russian is also used to describe the written language in Russia until the 18th century,[16] when it became Modern Russian, though the early stages of the language is often called Old East Slavic instead;[17] the period after the common language of the East Slavs is sometimes distinguished as Middle Russian,[18] or Great Russian.[19]

Some scholars have also called the language Old Rus'ian[20] or Old Rusan,[21] Rusian, or simply Rus,[22][23] although these are the least commonly used forms.[24]

Ukrainian-American linguist George Shevelov used the term Common Russian or Common Eastern Slavic to refer to the hypothetical uniform language of the East Slavs.[25]

American Slavist Alexander M. Schenker pointed out that modern terms for the medieval language of the East Slavs varied depending on the political context.[26] He suggested using the neutral term East Slavic for that language.[27]

General considerations

[edit]

The language was a descendant of the Proto-Slavic language and retained many of its features. It developed so-called pleophony (or polnoglasie 'full vocalisation'), which came to differentiate the newly evolving East Slavic from other Slavic dialects. For instance, Common Slavic *gȏrdъ 'settlement, town' was reflected as OESl. gorodъ,[28] Common Slavic *melkò 'milk' > OESl. moloko,[29] and Common Slavic *kòrva 'cow' > OESl korova.[30] Other Slavic dialects differed by resolving the closed-syllable clusters *eRC and *aRC as liquid metathesis (South Slavic and West Slavic), or by no change at all (see the article on Slavic liquid metathesis and pleophony for a detailed account).

Since extant written records of the language are sparse, it is difficult to assess the level of its unity. In consideration of the number of tribes and clans that constituted Kievan Rus', it is probable that there were many dialects of Old East Slavonic. Therefore, today we may speak definitively only of the languages of surviving manuscripts, which, according to some interpretations, show regional divergence from the beginning of the historical records. By c. 1150, it had the weakest local variations among the four regional macrodialects of Common Slavic, c. 800 – c. 1000, which had just begun to differentiate into its branches.[31]

With time, it evolved into several more diversified forms; following the fragmentation of Kievan Rus' after 1100, dialectal differentiation accelerated.[32] The regional languages were distinguishable starting in the 12th or 13th century.[33] Thus different variations evolved of the Russian language in the regions of Novgorod, Moscow, South Russia and meanwhile the Ukrainian language was also formed. Each of these languages preserves much of the Old East Slavic grammar and vocabulary. The Russian language in particular borrows more words from Church Slavonic than does Ukrainian.[34]

However, findings by Russian linguist Andrey Zaliznyak suggest that, until the 14th or 15th century, major language differences were not between the regions occupied by modern Belarus, Russia and Ukraine,[35] but rather between the north-west (around modern Velikiy Novgorod and Pskov) and the center (around modern Kyiv, Suzdal, Rostov, Moscow as well as Belarus) of the East Slavic territories.[36] The Old Novgorodian dialect of that time differed from the central East Slavic dialects as well as from all other Slavic languages much more than in later centuries.[37][38] According to Zaliznyak, the Russian language developed as a convergence of that dialect and the central ones,[39] whereas Ukrainian and Belarusian were continuation of development of the central dialects of the East Slavs.[40]

Also, Russian linguist Sergey Nikolaev, analysing historical development of Slavic dialects' accent system, concluded that a number of other tribes in Kievan Rus' came from different Slavic branches and spoke distant Slavic dialects.[41][page needed]

Another Russian linguist, G. A. Khaburgaev,[42] as well as a number of Ukrainian linguists (Stepan Smal-Stotsky, Ivan Ohienko, George Shevelov, Yevhen Tymchenko, Vsevolod Hantsov, Olena Kurylo), deny the existence of a common Old East Slavic language at any time in the past.[43] According to them, the dialects of East Slavic tribes evolved gradually from the common Proto-Slavic language without any intermediate stages.[44]

Following the end of the "Tatar yoke", the territory of former Kievan Rus' was divided between the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the Grand Duchy of Moscow,[45] and two separate literary traditions emerged in these states, Ruthenian in the west and medieval Russian in the east.[46][47][48]

Literary language

[edit]

The political unification of the region into the state called Kievan Rus', from which modern Belarus, Russia and Ukraine trace their origins, occurred approximately a century before the adoption of Christianity in 988 and the establishment of the South Slavic Old Church Slavonic as the liturgical and literary language. Documentation of the Old East Slavic language of this period is scanty, making it difficult at best fully to determine the relationship between the literary language and its spoken dialects.

There are references in Byzantine sources to pre-Christian Slavs in European Russia using some form of writing. Despite some suggestive archaeological finds and a corroboration by the tenth-century monk Chernorizets Hrabar that ancient Slavs wrote in "strokes and incisions", the exact nature of this system is unknown.

Although the Glagolitic alphabet was briefly introduced, as witnessed by church inscriptions in Novgorod, it was soon entirely superseded by Cyrillic.[49][citation needed] The samples of birch-bark writing excavated in Novgorod have provided crucial information about the pure tenth-century vernacular in North-West Russia, almost entirely free of Church Slavonic influence. It is also known that borrowings and calques from Byzantine Greek began to enter the vernacular at this time, and that simultaneously the literary language in its turn began to be modified towards Eastern Slavic.

The following excerpts illustrate two of the most famous literary monuments.

NOTE: The spelling of the original excerpt has been partly modernized. The translations are best attempts at being literal, not literary.

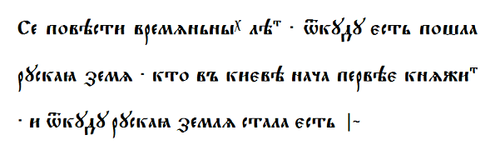

Primary Chronicle

[edit]c. 1110, from the Laurentian Codex, 1377:

| Original | Transliteration | |

|---|---|---|

| Old East Slavic[50][51] | Се повѣсти времѧньных лѣт ‧ ѿкꙋдꙋ єсть пошла рꙋскаꙗ земѧ ‧ кто въ києвѣ нача первѣє кнѧжит ‧ и ѿкꙋдꙋ рꙋскаꙗ землѧ стала єсть |~ | Se pověsti vremęnǐnyx lět, otkudu estǐ pošla ruskaja zemę, kto vǔ kievě nača pervěe knęžit, i otkudu ruskaja zemlę stala estǐ. |

| Russian[52][53] | Вот повести минувших лет, откуда пошла русская земля, кто в Киеве начал первым княжить, и откуда русская земля стала быть. | Vot povesti minuvšix let, otkuda pošla russkaja zemlja, kto v Kieve načal pervym knjažit', i otkuda russkaja zemlja stala byt'. |

| Ukrainian[54] | Це повісті минулих літ, звідки пішла руська земля, хто в Києві почав перший княжити, і звідки руська земля стала бути. | Ce povisti minulyx lit, zvidky pišla rus'ka zemlja, xto v Kyjevi počav peršyj knjažyty, i zvidky rus'ka zemlja stala buty. |

| Belarusian[55] | Вось аповесці мінулых гадоў: адкуль пайшла руская зямля, хто ў Кіеве першым пачаў княжыць, і адкуль руская зямля паўстала. | Vos' apovesci minulyx hadoŭ: adkul' pajšla ruskaja zjamlja, xto ŭ Kieve peršym pačaŭ knjažyc', i adkul' ruskaja zjamlja paŭstala. |

| Rusyn | Сись повісти минулых ріків, витки пушла руська земля, хто у Кієве почал первым князити, і витки руська земля постава є. | Sîs' povistî mînulyx rikiv, vîtkî pušla rus'ka zemlja, xto u Kijeve počal pervym knjazîtî, i vîtkî rus'ka zemlja postava je. |

| English[56] | These are the narratives of bygone years regarding the origin of the land of Rus', the first princes of Kiev, and from what source the land of Rus' had its beginning. |

In this usage example of the language, the fall of the yers is in progress or arguably complete: several words end with a consonant, e.g. кнѧжит, knęžit "to rule" < кънѧжити, kǔnęžiti (modern Uk княжити, knjažyty, R княжить, knjažit', B княжыць, knjažyc'). South Slavic features include времѧньнъıх, vremęnǐnyx "bygone" (modern R минувших, minuvšix, Uk минулих, mynulyx, B мінулых, minulyx). Correct use of perfect and aorist: єсть пошла, estǐ pošla "is/has come" (modern B пайшла, pajšla, R пошла, pošla, Uk пішла, pišla), нача, nača "began" (modern Uk почав, B пачаў, pačaŭ, R начал, načal) as a development of the old perfect. Note the style of punctuation.

The Tale of Igor's Campaign

[edit]Слово о пълку Игоревѣ. c. 1200, from the Pskov manuscript, fifteenth cent.

| Original | Transliteration | |

|---|---|---|

| Old East Slavic | Не лѣпо ли ны бяшетъ братїє, начяти старыми словесы трудныхъ повѣстїй о пълку Игоревѣ, Игоря Святъславлича? Начати же ся тъй пѣсни по былинамъ сего времени, а не по замышленїю Бояню. Боянъ бо вѣщїй, аще кому хотяше пѣснь творити, то растѣкашется мыслію по древу, сѣрымъ вълкомъ по земли, шизымъ орломъ подъ облакы.[57] | Ne lěpo li ny bjašetǔ bratije, načjati starymi slovesy trudnyxǔ pověstij o pǔlku Igorevě, Igorja Svjatǔslaviča? Načati že sja tǔj pěsni po bylinamǔ sego vremeni, a ne po zamyšleniju Bojanju. Bojanǔ bo věščij, ašče komu xotjaše pěsnǐ tvoriti, to rastěkašetsja mysliju po drevu, sěrymǔ vǔlkomǔ po zemli, šizymǔ orlomǔ podǔ oblaky. |

| Russian | Не пристало ли нам, о братья, начать старыми словами печальные повести о полку Игореве, Игоря Святославича? Начаться же песни этой по правде того времени, а не по замыслам Бояна. Ибо Боян вещий, если он хотел посвятить кому-то песнь, то растекался мыслью по дереву, серым волком по земле, сизым орлом под облаками. | Ne pristalo li nam, o brat'ja, načat' starymi slovami pečal'nye povesti o polku Igoreve, Igorja Svjatoslaviča? Načat'sja že pesni etoj po pravde togo vremeni, a ne po zamyslam Bojana. Ibo Bojan veščij, esli on xotel posvjagig' komu-to pesn', to rastekalsja mysl'ju po derevu, serym volkom po zemle, sizym orlom pod oblakami. |

| Ukrainian | Не личило б нам, о браття, почати старими словами сумні повісті про похід Ігоровий, Ігоря Святославича? Початись же цій пісні по правді того часу, а не по задумам Бояна. Бо Боян віщий, якщо він хотів присвятити комусь піснь, то розтікався думкою по дереву, сірим вовком по землї, сизим орлом під хмарами. | Ne lyčylo b nam, o brattja, počaty starymy slovamy sumni povisti pro poxid Ihorovyj, Ihorja Svjatoslavyča? Počatys' že cij pisni po pravdi toho času, a ne po zadumam Bojana. Bo Bojan viščyj, jakščo vin xotiv prysvjatyty komus' pisn', to roztikavsja dumkoju po derevu, sirym vovkom po zemlï, syzym orlom pid xmaramy. |

| Belarusian | Не належала б нам, о браты, пачаць старымі словамі баявыя аповесці аб паходзе Ігаравым, Ігара Святаславіча? Пачацца жа гэтай песні па праўдзе таго часу, а не па задумах Баяна. Бо Баян прарочы, калі ён хацеў прысвяціць камусьці песню, то расцякаўся думкаю па дрэве, шэрым ваўком па зямлі, шызым арлом пад аблокамі. | Ne nalježala b nam, o braty, pačac' starymi slovami bajavyja apovjesci ab pahodzje Iharavym, Ihara Svjataslaviča? Pačacca ža hetaj pjesni na praŭdze taho času, a ne pa zadumax Bajana. Bo Bajan praročy, kali jon xacjeŭ prysvjacic' kamus'ci pjesnju, to rascjakaŭsja dumkaju pa drevje, šerym vaŭkom pa zjamli, šyzym arlom pad ablokami. |

| Rusyn | Не подобало ли бы нам, о браття, зачати старыми словами боёве повістью о поход Іґорїв, про Іґоря Святославиче? І разначати путью по-правдивому тоґо часу, а не по замыслами Бояна. Бо Боян віщый, щи он хотїв придїлити комусь ростїкати ся мыслью по древу, як сїрым вовком велькым по землї, сивым орлом под хмарами. | Ne podobalo lî by nam, o brattja, začatî starymî slovamî bojeve povist'ju o poxod Igorïv, pro Igorja Svjatoslavîče? I raznačatî put'ju po-pravdîvomu togo času, a ne po zamyslamî Bojana. Bo Bojan viščyj, ščî on xotïv prîdïlîtî komus' rostïkatî sja mysl'ju po dremu, jak sïrym vovkom vel'kym po zemlï, sîvym orlom pod xmaramî. |

| English | Would it not be meet, o brothers, for us to begin with the old words the martial telling of the host of Igor, of Igor Sviatoslavlich? And to begin this tale in the way of the true tales of this time, and not in the way of Bojan's inventions. For the wise Bojan, if he wished to devote to someone [his] song, would fly like a squirrel in the trees, like a grey wolf over land, like a bluish eagle beneath the clouds. |

Illustrates the sung epics, with typical use of metaphor and simile.

It has been suggested that the phrase растекаться мыслью по древу (rastekat'sja mysl'ju po drevu, to run in thought upon/over wood), which has become proverbial in modern Russian with the meaning "to speak ornately, at length, excessively," is a misreading of an original мысію, mysiju (akin to мышь "mouse") from "run like a squirrel/mouse on a tree"; however, the reading мыслью, myslǐju is present in both the manuscript copy of 1790 and the first edition of 1800, and in all subsequent scholarly editions.

Old East Slavic literature

[edit]The Old East Slavic language developed a certain literature of its own, though much of it (in hand with those of the Slavic languages that were, after all, written down) was influenced as regards style and vocabulary by religious texts written in Church Slavonic. Surviving literary monuments include the legal code Russkaya Pravda, a corpus of hagiography and homily, The Tale of Igor's Campaign, and the earliest surviving manuscript of the Primary Chronicle – the Laurentian Codex of 1377.

The earliest dated specimen of Old East Slavic (or, rather, of Church Slavonic with pronounced East Slavic interference) must be considered the written Sermon on Law and Grace by Hilarion, metropolitan of Kiev. In this work there is a panegyric on Prince Vladimir of Kiev, the hero of so much of East Slavic popular poetry. It is rivalled by another panegyric on Vladimir, written a decade later by Yakov the Monk.

Other 11th-century writers are Theodosius, a monk of the Kiev Pechersk Lavra, who wrote on the Latin faith and some Pouchenia or Instructions, and Luka Zhidiata, bishop of Novgorod, who has left a curious Discourse to the Brethren. From the writings of Theodosius we see that many pagan habits were still in vogue among the people. He finds fault with them for allowing these to continue, and also for their drunkenness; nor do the monks escape his censures. Zhidiata writes in a more vernacular style than many of his contemporaries; he eschews the declamatory tone of the Byzantine authors. And here may be mentioned the many lives of the saints and the Fathers to be found in early East Slavic literature, starting with the two Lives of Sts Boris and Gleb, written in the late eleventh century and attributed to Jacob the Monk and to Nestor the Chronicler.

With the so-called Primary Chronicle, also attributed to Nestor, begins the long series of the Russian annalists. There is a regular catena of these chronicles, extending with only two breaks to the seventeenth century. Besides the work attributed to Nestor the Chronicler, there are the chronicles of Novgorod, Kiev, Volhynia and many others. Every town of any importance could boast of its annalists, Pskov and Suzdal among others.

In the 12th century, we have the sermons of bishop Cyril of Turov, which are attempts to imitate in Old East Slavic the florid Byzantine style. In his sermon on Holy Week, Christianity is represented under the form of spring, Paganism and Judaism under that of winter, and evil thoughts are spoken of as boisterous winds.

There are also the works of early travellers, as the igumen Daniel, who visited the Holy Land at the end of the eleventh and beginning of the twelfth century. A later traveller was Afanasiy Nikitin, a merchant of Tver, who visited India in 1470. He has left a record of his adventures, which has been translated into English and published for the Hakluyt Society.

A curious monument of old Slavonic times is the Pouchenie ("Instruction"), written by Vladimir Monomakh for the benefit of his sons. This composition is generally found inserted in the Chronicle of Nestor; it gives a fine picture of the daily life of a Slavonic prince. The Paterik of the Kievan Caves Monastery is a typical medieval collection of stories from the life of monks, featuring devils, angels, ghosts, and miraculous resurrections.

Lay of Igor's Campaign narrates the expedition of Igor Svyatoslavich, the prince of Novgorod-Seversk, against the Cumans. It is neither epic nor a poem but is written in rhythmic prose. An interesting aspect of the text is its mix of Christianity and ancient Slavic religion. Igor's wife Yaroslavna famously invokes natural forces from the walls of Putyvl. Christian motifs present along with depersonalised pagan gods in the form of artistic images. Another aspect, which sets the book apart from contemporary Western epics, are its numerous and vivid descriptions of nature, and the role which nature plays in human lives. Of the whole bulk of the Old East Slavic literature, the Lay is the only work familiar to every educated Russian or Ukrainian. Its brooding flow of images, murky metaphors, and ever changing rhythm have not been successfully rendered into English yet. Indeed, the meanings of many words found in it have not been satisfactorily explained by scholars.

The Zadonshchina is a sort of prose poem much in the style of the Tale of Igor's Campaign, and the resemblance of the latter to this piece furnishes an additional proof of its genuineness. This account of the Battle of Kulikovo, which was gained by Dmitry Donskoy over the Mongols in 1380, has come down in three important versions.

The early laws of Rus’ present many features of interest, such as the Russkaya Pravda of Yaroslav the Wise, which is preserved in the chronicle of Novgorod; the date is between 1018 and 1072.

Study

[edit]The earliest attempts to compile a comprehensive lexicon of Old East Slavic were undertaken by Alexander Vostokov and Izmail Sreznevsky in the nineteenth century. Sreznevsky's Materials for the Dictionary of the Old Russian Language on the Basis of Written Records (1893–1903), though incomplete, remained a standard reference until the appearance of a 24-volume academic dictionary in 1975–99.

Notable texts

[edit]

- Bylinas

- The Tale of Igor's Campaign – the most outstanding literary work in this language

- Russkaya Pravda – an eleventh-century legal code issued by Yaroslav the Wise

- Praying of Daniel the Immured

- A Journey Beyond the Three Seas

See also

[edit]- Old Russians

- Outline of Slavic history and culture

- List of Slavic studies journals

- History of the East Slavic languages

- List of Latvian words borrowed from Old East Slavic

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ SIL 2022.

- ^ Shevelov 1984, section 1.

- ^ Magocsi 2010, p. 106.

- ^ Shevelov 1984, section 1: "Chronologically, Common Russian is considered by some to have existed from the 7th or 8th century to the 13th or 14th century (Aleksei Sobolevsky, Vatroslav Jagić, Fedot Filin, et al) and by others only to the 10th or 11th century (Oleksander Potebnia, Ahatanhel Krymsky, and, in part, Leonid Bulakhovsky)".

- ^ Pugh 1996, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Pugh1985, pp. 53–60.

- ^ Krause & Slocum 2013, section 1: "…a more appropriate term for the language is Old East Slavic. Unfortunately, in addition to being cumbersome, this terminology is not universally applied even within modern scholarship".

- ^ Yartseva & Arutyunova 1990.

- ^ Britannica.

- ^ Krause & Slocum 2013, section 1: "The title Old Russian serves to denote the language of the earliest documents of the eastern branch of the Slavic family of languages".

- ^ Langston 2018, p. 1405: "The language of the oldest texts from the period of Kievan Rus’ is often referred to loosely as Old Russian".

- ^ Schenker 1995, p. 74: "In the pre-Petrine period, the language of literary texts was Church Slavonic in its East Slavic recension, which together with the language of subliterary documents is commonly referred to as Old Russian. This term, however, may be viewed as anachronistic, for at that time East Slavic had not yet diverged into Russian, Ukrainian, and Belarussian".

- ^ Krause & Slocum 2013, section 1: "Thus Old Russian serves as a common parent to all three of the major East Slavic languages, and as such a more appropriate term for the language is Old East Slavic".

- ^ Magocsi 2010, p. 73: "For the longest time, English-language writings did not distinguish the name Rus' from Russia, with the result that in descriptions of the pre-fourteenth-century Kievan realm the conceptually distorted formulation Kievan Russia was used. In recent years, however, the correct terms Rus' and Kievan Rus' have appeared more frequently in English-language scholarly publications, although the corresponding adjective Rus'/Rusyn has been avoided in favor of either the incorrect term Russian or the correct but visually confusing term Rus'ian/Rusian".

- ^ Langston 2018, p. 1405: "…but these documents are mostly Church Slavic with varying degrees of influence from the vernacular, and the local features that they exhibit are better characterized as Common East Slavic in most instances".

- ^ Fortson 2011, p. 429.

- ^ Bermel 1997, p. 17.

- ^ Matthews 2013, p. 112.

- ^ Vinokur 1971, pp. 19–20, "For the period after the 14th century, however, the term 'Russian language' is equivalent to the term 'Great-Russian' and distinguishes the Russian language in the modern sense from the languages of the Ukraine and Belorussia".

- ^ Moser, Michael (2016-12-06). New Contributions to the History of the Ukrainian Language. University of Alberta Press. pp. xi. ISBN 978-1-894865-44-9.

- ^ Moser, Michael (2022-11-01). "The late origins of the glottonym "русский язык"". Russian Linguistics. 46 (3): 365–370. doi:10.1007/s11185-022-09257-6. ISSN 1572-8714.

- ^ Lunt 2001, p. 184: "I call the common (North) East Slavic language (up to the first half of the 14th century) Rusian".

- ^ Magocsi 2010, p. 106-108.

- ^ Krause & Slocum 2013, section 1: "…some scholars employ the term Rusian for Old Russian. This is perhaps the most convenient of all the terms, but lamentably it is also the least commonly used".

- ^ Shevelov 1984, section 1: "Common Russian (also called Common Eastern Slavic). The name of the hypothetical uniform language of the Eastern Slavs, which presumably arose after the disintegration of Common Slavic and which itself later disintegrated to form three new languages: Ukrainian, Russian, and Belarusian".

- ^ Schenker 1995, p. 74: "Depending on the local political situation the terms Old Russian, Old Ukrainian, and Old Belarussian have been applied to essentially the same body of texts".

- ^ Schenker 1995, p. 74: "It seems more appropriate, therefore, to use the general and neutral term East Slavic and indicate its dialectical varieties".

- ^ Derksen 2008, p. 178: "*gȏrdъ m. o (c) 'fortification, town' … E Ru. górod 'town, city', Gsg. góroda; Bel. hórad 'town, city', Gsg. hórada; Ukr. hórod 'town, city', Gsg. hóroda".

- ^ Derksen 2008, p. 307: "*melkò n. o (b) 'milk' … E Ru. molokó".

- ^ Derksen 2008, p. 236: "*kòrva f. ā (a) 'cow' … E Ru. koróva".

- ^ Lunt 2001, p. 184: "the Late Common Slavic of c1000 CE had four regional variants or macro dialects: NorthWest, SouthWest, SouthEast, NorthEast. . . . by c1150 . . . [East Slavic] was still a single language, with the weakest of local variations".

- ^ Byram, Michael; Hu, Adelheid (26 June 2013). Routledge Encyclopedia of Language Teaching and Learning. Routledge. p. 601. ISBN 978-1-136-23554-2.

- ^ Lotha et al. 2022, section 2: "Like Belarusian, the Ukrainian language contains a large number of words borrowed from Polish, but it has fewer borrowings from Church Slavonic than does Russian".

- ^ Zaliznyak 2012, section 111: "…ростовско-суздальско-рязанская языковая зона от киевско-черниговской ничем существенным в древности не отличалась. Различия возникли позднее, они датируются сравнительно недавним, по лингвистическим меркам, временем, начиная с XIV–XV вв […the Rostov-Suzdal-Ryazan language area did not significantly differ from the Kiev-Chernigov one. Distinctions emerged later, in a relatively recent, by linguistic standards, time, starting from the 14th–15th centuries]".

- ^ Zaliznyak 2012, section 88: "Северо-запад — это была территория Новгорода и Пскова, а остальная часть, которую можно назвать центральной, или центрально-восточной, или центрально-восточно-южной, включала одновременно территорию будущей Украины, значительную часть территории будущей Великороссии и территории Белоруссии … Существовал древненовгородский диалект в северо-западной части и некоторая более нам известная классическая форма древнерусского языка, объединявшая в равной степени Киев, Суздаль, Ростов, будущую Москву и территорию Белоруссии [The territory of Novgorod and Pskov was in the north-west, while the remaining part, which could either be called central, or central-eastern, or central-eastern-southern, comprised the territory of the future Ukraine, a substantial part of the future Great Russia, and the territory of Belarus … The Old Novgorodian dialect existed in the north-western part, while a somewhat more well-known classical variety of the Old Russian language united equally Kiev, Suzdal, Rostov, the future Moscow and the territory of Belarus]".

- ^ Zaliznyak 2012, section 82: "…черты новгородского диалекта, отличавшие его от других диалектов Древней Руси, ярче всего выражены не в позднее время, когда, казалось бы, они могли уже постепенно развиться, а в самый древний период […features of the Novgorodian dialect, which made it different from the other dialects of the Old Rus', were most pronounced not in later times, when they seemingly could have evolved, but in the oldest period]".

- ^ Zaliznyak 2012, section 92: "…северо-западная группа восточных славян представляет собой ветвь, которую следует считать отдельной уже на уровне праславянства […north-western group of the East Slavs is a branch that should be regarded as separate already in the Proto-Slavic period]".

- ^ Zaliznyak 2012, section 94: "…великорусская территория оказалась состоящей из двух частей, примерно одинаковых по значимости: северо-западная (новгородско-псковская) и центрально-восточная (Ростов, Суздаль, Владимир, Москва, Рязань) […the Great Russian territory happened to include two parts of approximately equal importance: the north-western one (Novgorod-Pskov) and the central-eastern-southern one (Rostov, Suzdal, Vladimir, Moscow, Ryazan)]".

- ^ Zaliznyak 2012, section 94: "…нынешняя Украина и Белоруссия — наследники центрально-восточно-южной зоны восточного славянства, более сходной в языковом отношении с западным и южным славянством […today's Ukraine and Belarus are successors of the central-eastern-southern area of the East Slavs, more linguistically similar to the West and South Slavs]".

- ^ Dybo, Zamyatina & Nikolaev 1990.

- ^ Khaburgaev 2005, p. 418-437.

- ^ Nimchuk 2001.

- ^ Shevelov 1979.

- ^ Chauhan 2012.

- ^ Kolodziejczyk, Dariusz (22 June 2011). The Crimean Khanate and Poland-Lithuania: International Diplomacy on the European Periphery (15th–18th Century), A Study of Peace Treaties Followed by an Annotated Edition of Relevant Documents. BRILL. p. 241. ISBN 978-90-04-21571-9.

- ^ Woolhiser, Curt Fredric (1995). Polish and Belorussian Dialects in Contact: A Study in Linguistic Convergence. Indiana University. p. 90.

- ^ Rhyne, George N.; Lazzerini, Edward J.; Adams, Bruce Friend (2003). The Supplement to The Modern Encyclopedia of Russian, Soviet and Eurasian History: Bashkir Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic – Bugaev, Boris Nikolaevich. Academic International Press. p. 89. ISBN 978-0-87569-142-8.

- ^ Vinokur 1971, p. 27: "There are no extant Old Russian manuscripts written entirely in Glagolitic. There are however Russian Cyrillic manuscripts in which isolated words and lines in Glagolitic occur".

- ^ RSL.

- ^ Izbornyk2.

- ^ NLR, section 1: "Вот повести минувших лет, откуда пошла русскaя земля, кто в Киеве стал первым княжить, и как возникла русская земля".

- ^ BBM.

- ^ LUL, section 1: "Повість минулих літ Нестора, чорноризця Феодосієвого монастиря Печерського, звідки пішла Руська земля, і хто в ній почав спершу княжити, як Руська земля постала".

- ^ Karotki 2004, p. 4: "Вось аповесці мінулых гадоў: адкуль пайшла руская зямля, хто ў Кіеве першым пачаў княжыць, і адкуль руская зямля паўстала".

- ^ Cross & Sherbowitz-Wetzor 1953, p. 51: "These are the narratives of bygone years regarding the origin of the land of Rus', the first princes of Kiev, and from what source the land of Rus' had its beginning".

- ^ Izbornyk1.

Bibliography

[edit]- "Povest' Vremennykh Let" Повесть временных лет [Primary Chronicle]. BBM Online Library (in Russian). Archived from the original on 2013-06-24. Retrieved 2020-08-22.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - "Old Russian". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 14 July 2022.

- Chauhan, Yamini, ed. (25 May 2012). "Grand Principality of Moscow | medieval principality, Russia". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2022-12-31.

- Karotki, Uladzimir, ed. (2004). Staražytnaja litaratura uschodnich slavian XI – XIII stahoddziaŭ Старажытная літаратура ўсходніх славян ХІ – ХІІІ стагоддзяў [Old Literature of the East Slavs in the 11th–13th Centuries] (PDF) (in Belarusian). Translated by Karotki, Uladzimir; Nekrashevich-Karotkaya, Zhanna; Kayala, U. I. Grodno.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 25 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 227–228.

- Cross, Samuel Hazzard; Sherbowitz-Wetzor, Olgerd P. (1953). The Russian Primary chronicle: Laurentian Text. Cambridge, MA: Mediaeval Academy of America. ISBN 9780915651320.

- Derksen, Rick (2008). Etymological Dictionary of the Slavic Inherited Lexicon. Leiden-Boston: Koninklijke Brill NV. ISBN 978-90-04-15504-6. ISSN 1574-3586.

- Dybo, V. A.; Zamyatina, G. I.; Nikolaev, S. L. (1990). Bulatova, R.V. (ed.). Osnovy slavyanskoy aktsentologii Основы славянской акцентологии [Fundamentals of Slavic Accentology] (in Russian). Moscow: Nauka. ISBN 5-02-011011-6.

- "Slovo o polku Ihorevim" СЛОВО О ПЛЪКУ ИГОРЕВЂ. Слово о полку Ігоревім. Слово о полку Игореве [The Tale of Igor's Campaign]. Izbornyk (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 2022-12-22.

- "Letopis' po Lavrent'evskomu spisku" Лѣтопись по Лаврентьевскому списку [Laurentian Codex]. Izbornyk (in Russian).

- Khaburgaev, Georgiy Alexandrovich (2005). "Drenverusskiy Yazyk" Древнерусский язык [Old Russian]. In Moldovan, A. M.; et al. (eds.). Yazyki mira. Slavyanskie Yazyki Языки мира. Славянские языки [Languages of the World. Slavic Languages] (in Russian). Moscow: Academia. pp. 418–437.

- Krause, Todd B.; Slocum, Jonathan (2013). "Old Russian Online, Series Introduction". Early Indo-European Online Language Lessons. University of Texas at Austin. Retrieved 2022-12-25.

- Langston, Keith (2018). "The documentation of Slavic". In Jared Klein; Brian Joseph; Matthias Fritz (eds.). Handbook of Comparative and Historical Indo-European Linguistics. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. pp. 1397–1413. ISBN 9783110542431.

- Lotha, Gloria; Kuiper, Kathleen; Mahajan, Deepti; Shukla, Gaurav, eds. (13 September 2022). "Ukrainian Language". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2022-12-31.

- "Povist' minulikh lit" Повість минулих літ [Primary Chronicle]. The Library of Ukrainian Literature (in Ukrainian).

- Lunt, Horace G. (2001). Old Church Slavonic Grammar (seventh ed.). Berlin: Mouton De Gruyter. p. 184. ISBN 3110162849.

- Magocsi, Paul Robert (2010). A history of Ukraine: the land and its peoples (2nd ed.). Toronto: University of Toronto press. ISBN 978-1-4426-4085-6.

- Minns, Ellis Hovell (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 25 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 228–237.

- "Laurentian Codex. 1377". The National Library of Russia.

- Nimchuk, V. V. (2001). "9.1. Mova" 9.1. Мова [9.1. The Language]. In Smoliy, V. A. (ed.). Istoriia ukrains'koi kultury Історія української культури [A History of the Ukrainian Culture] (in Ukrainian). Vol. 1. Kyiv: Naukova Dumka. Retrieved 2022-12-25.

- Ostrowski, Donald (2018). Portraits of Medieval Eastern Europe, 900–1400. Christian Raffensperger. Abingdon, Oxon. ISBN 978-1-315-20417-8. OCLC 994543451.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - "Laurentian Codex". Russian State Library.

- Schenker, Alexander M. (1995). The Dawn of Slavic: An Introduction to Slavic Philology. New Haven / London: Yale University Press. ISBN 0300058462.

- Shevelov, George Yurii (1984). "Common Russian". Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine. Retrieved 2022-12-25.

- George Shevelov (1979). A Historical Phonology of the Ukrainian Language. Historical Phonology of the Slavic Languages. Heidelberg: Universitätsverlag C. Winter. ISBN 3-533-02786-4. OL 22276820M. Wikidata Q105081119.

- Shevelov, George Yurii (1963). "History of the Ukrainian Language". In Volodymyr Kubijovyč; et al. (eds.). Ukraine: A Concise Encyclopaedia. Vol. I. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-3105-6. LCCN 63023686. OL 7872840M. Wikidata Q12072836.

- Shevelov, George Yurii (1979). Istorychna fonologiia ukrains'koi movy Історична фонологія української мови [A Historical Phonology of the Ukrainian Language] (in Ukrainian). Translated by Vakulenko, Serhiy; Danilenko, Andriy. Kharkiv: Acta (published 2000). Retrieved 2022-12-25.

- "639 Identifier Documentation: orv". SIL International (formerly known as the Summer Institute of Linguistics). 2022. Retrieved 25 December 2022.

- Simone, Lucas Ricardo (2018). "Uma breve introdução ao idioma eslavo oriental antigo" [A Brief Introduction to the Old East Slavic Language]. Slovo – Revista de Estudos em Eslavística (in Portuguese). 1 (1): 14–39.

- Vinokur, G. O. (1971). Forsyth, James (ed.). The Russian Language: A Brief History. Translated by Forsyth, Mary A. Cambridge: Cambridge University. ISBN 0521079446.

- Yartseva, V. N.; Arutyunova, N. D. (1990). Lingvisticheskiĭ ėnt︠s︡iklopedicheskiĭ slovarʹ Лингвистический энциклопедический словарь [Linguistic Encyclopedic Dictionary] (in Russian). I︠A︡rt︠s︡eva, V. N. (Viktorii︠a︡ Nikolaevna), 1906–1999., Aruti︠u︡nova, N. D. (Nina Davidovna), Izdatelʹstvo "Sovetskai︠a︡ ėnt︠s︡iklopedii︠a︡." Nauchno-redakt︠s︡ionnyĭ sovet., Institut i︠a︡zykoznanii︠a︡ (Akademii︠a︡ nauk SSSR). Moscow: Sov. ėnt︠s︡iklopedii︠a︡. p. 143. ISBN 5-85270-031-2. OCLC 23704551.

- Zaliznyak, Andrey Anatolyevich (2012). "Ob istorii russkogo yazyka" Об истории русского языка [About Russian Language History]. Elementy (in Russian). Mumi-Troll School. Retrieved 2022-12-25.

- Pugh, Stefan M. (1985). "The Ruthenian Language of Meletij Smotryc'kyj: Phonology". Harvard Ukrainian Studies. 9 (1/2): 53–60. JSTOR 41036132.

- Bermel, Neil (1 January 1997). Context and the Lexicon in the Development of Russian Aspect. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-09812-1.

- Fortson, Benjamin W. (7 September 2011). Indo-European Language and Culture: An Introduction. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4443-5968-8.

- Pugh, Stefan M. (1996). Testament to Ruthenian: A Linguistic Analysis of the Smotryc'kyj Variant. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780916458751.

- Matthews, W. K. (2013). The structure and development of Russian (First paperback ed.). Cambridge. ISBN 9781107619395.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

General references

[edit]- Entwistle, W. J.; Morison, W. A. (1960). Russian and the Slavonic Languages. London: Faber and Faber.

- Matthews, William Kleesmann (1967). Russian Historical Grammar. London: The Athlone Press, University of London.

- Schmalstieg, William R. (1995). "An introduction to Old Russian". Journal of Indo-European Studies Monograph Series (15). Washington, D.C.: Institute for the Study of Man. ISBN 0941694372.

- Vlasto, A. P. (1986). A Linguistic History of Russia to the End of the Eighteenth Century. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 019815660X.

- Moser, Michael (2016-12-06). New Contributions to the History of the Ukrainian Language. University of Alberta Press. ISBN 978-1-894865-44-9.

Further reading

[edit]External links

[edit]- Old Russian Online by Todd B. Krause and Jonathan Slocum, free online lessons at the Linguistics Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin

- Ostromir's Gospel Online

- Online library of the Old Russian texts (in Russian)

- The Pushkin House, a great 12-volumed collection of ancient texts of the 11th–17th centuries with parallel Russian translations

- Izbornyk, library of Old East Slavic chronicles with Ukrainian and Russian translations