Robert Sayer

Robert Sayer | |

|---|---|

portrait by Johan Zoffany | |

| Born | 1725 |

| Died | January 29, 1794 |

| Nationality | British |

| Occupations |

|

| Spouse(s) | Dorothy Carlos (or Careless) (m.1754, d.1774) Alice Tilson Longfield (m.1780) |

| Children | son, James |

Robert Sayer (1725–1794) was a leading publisher and seller of prints, maps and maritime charts in Georgian Britain. He was based near the Golden Buck on 53 Fleet Street in London.[1][2]

Printing Business

[edit]Sayer's brother James married the widowed Mary Overton, daughter-in-law of John Overton the printseller. Sayer became her assistant, being called manager of the Golden Buck by 1748, and in this way gradually took over the existing Overton business as a going concern.[3]

John Bennett, who began as a servant to Sayer in 1760, and later an apprentice (1765) and a free journeyman (1774), eventually partnered with Sayer with one-third share in the Fleet Street business. The business traded as Sayer & Bennett.[2] In 1781, Bennett was admitted to Dr Thomas Monro's Brook House asylum in Clapton. Sayer would seek to dissolve the partnership in 1785 based on Bennett's mental condition. Bennett later died in 1787.[4] Upon the partnership dissolution, the business was renamed Sayer & Co. or Robert Sayer & Co., probably a reference to his assistants Robert Laurie and James Whittle.[2]

Sayer published atlases and other cartographic works, publishing the Mundane System (1774) of Samuel Dunn and the famous North American Pilot (1775), which included important charts made by the great circumnavigator and explorer Captain James Cook.[5]

Sayer also had an "almost complete set of copies" of painter William Hograth's plates and sold prints at prices that undercut those of Hogarth's widow and printseller, Jane Hogarth.[6]

Harlequinades and turn-up books

[edit]

About 1765, Robert Sayer began experimenting with a novelty format for the juvenile book market, an early forerunner to interactive movable books, according to book historian Peter Haining. The outcome was the creation of the “metamorphoses” format, “a thin book of four sections each with two flaps which folded over, and on each section an interchangeable picture. Beneath those pictures appeared some descriptive lines of verse, and as the reader turned up the flaps in the correct order in the text difference scenes were revealed.”[7]

Originally called “metamorphosis”, Sayer would create books featuring the “Harlequins” from popular theater pantomimes. The black and white publications, which were also called Harlequinades or turn-up books, sold for sixpence and the hand-colored ones for one shilling.[7]

Sayers published at least fifteen such titles between 1766 and 1772.[8] Theater historian George Speaight noted that Sayers published at least sixteen titles.[9]

Titles Sayer printed and published include Harlequin Cherokee; or, The Indian Chiefs in London, published in 1772.[10] Academic Dr. Jacqueline Reid-Walsh has located eleven of Sayer's "harlequinades" in the rare book collections of Cambridge University Library, Cambridge, the Cotsen Children's Library, the Lilly Library in Bloomington, Indiana, the Opie Collection in the Bodleian Library, Oxford, the Osborne Collection in the Toronto Public Library, and the University of California, Los Angeles.[11]

By late 1770, Sayer had published four turn-up or metamorphosis books, which became a "craze with children."[12] Rival booksellers, such as Thomas Hughes and George Martin soon copied the "turn-up" format.[12] In the United States, Joseph Rakestraw published "Metamorphosis; or, a Transformation of Pictures, with Poetical Explanations, for the Amusement of Young Persons," by Benjamin Sands.

The Sayer Family of Richmond painting

[edit]Sayer organised the engraving of paintings by some leading artists of the day, most importantly Johan Zoffany RA, and sold prints from the engravings. In this way, he helped to secure Zoffany's international reputation. Sayer and the artist became longstanding friends as well as business associates. In 1781 Zoffany painted Robert Sayer in an important ‘conversation piece’. The Sayer Family of Richmond depicts Robert Sayer, his son, James, from his first marriage, and his second wife, Alice Longfield (née Tilson).[13] Behind the family group is the substantial villa on Richmond Hill overlooking the River Thames, built for Sayer between 1777 and 1780 to the designs of William Eves, a little-known architect and property developer. From 1794, after Robert Sayer's death, the house was the country residence for three years of the Duke of Clarence (later King William IV) and Mrs Jordan, and their three eldest (of ten) children. The third child was born at the house. Having fallen into disrepair, the house was demolished in 1970 when it was unknown that it had been built for Sayer and that it had subsequently been the home of a future king of Great Britain.[14]

Death

[edit]On his death, Sayer's business was taken over by Robert Laurie and James Whittle, both of whom had worked for him.[5]

Selected works

[edit]- Engravings and Prints

- Published by Robert Sayer

-

A New Book of Ornaments, MET DP270225, pre-1753.

-

Hudibras Vanquished by Trulla (Twelve Large Illustrations for Samuel Butler's Hudibras, Plate 5) MET DP826950, Artist, William Hogarth.

-

David Garrick by Charles Spooner, 1761.

-

Ladies Amusement, MET DP285711, 1760.

-

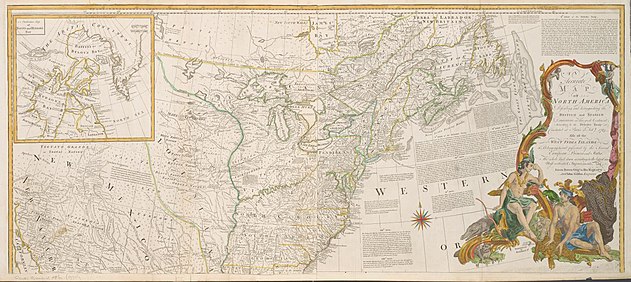

Accurate Map of North America, 1775 (top)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Robert Sayer (Biographical details)". Britishmuseum.org. 1920-05-18. Retrieved 2014-04-30.

- ^ a b c "Robert Sayer, Collections Online | British Museum". www.britishmuseum.org. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- ^ Clayton, Timothy. "Overton family". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/64997. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ "John Bennett, Collections Online | British Museum". www.britishmuseum.org. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- ^ a b Fisher, Susanna. "Sayer, Robert". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/50893. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Griffiths, Antony (1984). "A Checklist of Catalogues of British Print Publishers c. 1650-1830". Print Quarterly. 1 (1): 9–10. ISSN 0265-8305. JSTOR 41811970. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- ^ a b Haining, Peter (1979). Movable books: an illustrated history. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-450-03949-2. OCLC 8172362. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- ^ Montanaro, Ann R (1993). Pop-up and movable books: a bibliography. Scarecrow Press. p. xiv. ISBN 978-0-8108-2650-2. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- ^ Speaight, George (1991). "Harlequinade Turn-Ups". Theatre Notebook. 45 (2): 70–82.

- ^ Harlequin Cherokee, or, The Indian chiefs in London. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ Reid-Walsh, Jacqueline (2007). "Eighteenth-Century Flap Books for Children: Allegorical Metamorphosis and Spectacular Transformation". The Princeton University Library Chronicle. 68 (3): 751–790. doi:10.25290/prinunivlibrchro.68.3.0751. ISSN 0032-8456. JSTOR 10.25290/prinunivlibrchro.68.3.0751. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- ^ a b Quayle, Eric (1971). The collector's book of children's books. C.N. Potter; distributed by Crown Publishers. pp. 129–130. OCLC 577286008. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- ^ "Circle of Johann Zoffany, R.A." sothebys.com. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- ^ David Wilson, Johan Zoffany RA and The Sayer Family of Richmond: A Masterpiece of Conversation, London, 2014