Cinema of Italy

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

| Cinema of Italy | |

|---|---|

A collage of notable Italian actors and filmmakers[a] | |

| No. of screens | 3,217 (2013)[1] |

| • Per capita | 5.9 per 100,000 (2013)[1] |

| Main distributors | Medusa Film (16.7%) Warner Bros. (13.8%) 20th Century Studios (13.7%)[2] |

| Produced feature films (2018)[3] | |

| Total | 273 |

| Fictional | 180 |

| Documentary | 93 |

| Number of admissions (2018)[3] | |

| Total | 85,900,000 |

| • Per capita | 1.50 (2012)[4] |

| National films | 19,900,000 (23.17%) |

| Gross box office (2018)[3] | |

| Total | €555 million |

| National films | €128 million (23.03%) |

The cinema of Italy (Italian: cinema italiano, pronounced [ˈtʃiːnema itaˈljaːno]) comprises the films made within Italy or by Italian directors. Italy is widely considered one of the birthplaces of art cinema, and the stylistic aspect of Italian film has been one of the most important factors in the history of Italian film.[5][6] As of 2018, Italian films have won 14 Academy Awards for Best Foreign Language Film as well as 12 Palmes d'Or, one Academy Award for Best Picture and many Golden Lions and Golden Bears.

The history of Italian cinema began a few months after the Lumière brothers began motion picture exhibitions.[7][8] The first Italian director is considered to be Vittorio Calcina, a collaborator of the Lumière Brothers, who filmed Pope Leo XIII in 1896. The first films were made in the main cities of the Italian peninsula.[7][8] These brief experiments immediately met the curiosity of the general public, encouraging operators to produce new films and laying the foundation for the Italian film industry.[7][8] In the early 20th century, silent cinema developed, bringing numerous Italian stars to the forefront.[9] In the early 1900s, epic films such as Otello (1906), The Last Days of Pompeii (1908), L'Inferno (1911), Quo Vadis (1913), and Cabiria (1914), were made as adaptations of books or stage plays. The oldest European avant-garde cinema movement, Italian futurism, emerged in the late 1910s.[10] After a period of decline in the 1920s, the Italian film industry was revitalized in the 1930s with the arrival of sound film. A popular Italian genre during this period, the Telefoni Bianchi, consisted of comedies with glamorous backgrounds. Calligrafismo was in sharp contrast to Telefoni Bianchi-American style comedies and is rather artistic, highly formalistic, expressive in complexity and deals mainly with contemporary literary material. While Italy's Fascist government provided financial support for the nation's film industry, notably the construction of the Cinecittà studios, the largest film studio in Europe at the time. It also engaged in censorship, and thus many Italian films produced in the late 1930s were propaganda films.

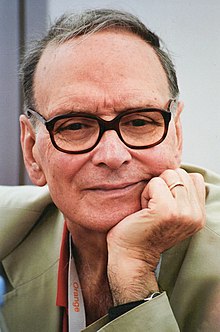

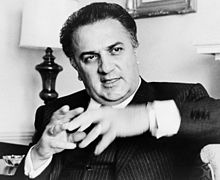

The end of World War II saw the birth of the influential Italian neorealist movement, which reached vast audiences throughout the post-war period,[11] and which launched the directorial careers of Luchino Visconti, Roberto Rossellini, and Vittorio De Sica. Neorealism declined in the late 1950s in favour of lighter films, such as those of the Commedia all'italiana genre and directors like Federico Fellini and Michelangelo Antonioni. Actresses such as Sophia Loren, Giulietta Masina, Claudia Cardinale, Monica Vitti, Anna Magnani and Gina Lollobrigida achieved international stardom during this period.[12] From the mid-1950s to the end of the 1970s, Commedia all'italiana and many other genres arose due to auteur cinema, and Italian cinema reached a position of great prestige both nationally and abroad.[13][14] The Spaghetti Western achieved popularity in the mid-1960s, peaking with Sergio Leone's Dollars Trilogy, which featured enigmatic scores by composer Ennio Morricone, which have become icons of the Western genre. Italian thrillers, or giallo, produced by directors such as Mario Bava and Dario Argento in the 1960s and 1970s, influenced the horror genre worldwide. During the 1980s and 1990s, directors such as Ermanno Olmi, Bernardo Bertolucci, Giuseppe Tornatore, Gabriele Salvatores and Roberto Benigni brought critical acclaim back to Italian cinema.[12]

The Venice Film Festival is the oldest film festival in the world, held annually since 1932 and awarding the Golden Lion.[15] In 2008 the Venice Days ("Giornate degli Autori"), a section held in parallel to the Venice Film Festival, has produced in collaboration with Cinecittà studios and the Ministry of Cultural Heritage a list of a 100 films that have changed the collective memory of the country between 1942 and 1978: the "100 Italian films to be saved".

History

[edit]1890s

[edit]The first Italian director is considered to be Vittorio Calcina, a collaborator of the Lumière Brothers, who filmed Pope Leo XIII on 26 February 1896 in the short film Sua Santità papa Leone XIII ("His Holiness Pope Leo XIII").[16] As the official photographer of the House of Savoy,[17] he filmed the first Italian film, Sua Maestà il Re Umberto e Sua Maestà la Regina Margherita a passeggio per il parco a Monza ("His Majesty the King Umberto and Her Majesty the Queen Margherita strolling through the Monza Park").[18] In 1895, Filoteo Alberini patented his "kinetograph," a shooting and projecting device not unlike that of the Lumière brothers.[12][19]

The Lumière brothers commenced public screenings in Italy in 1896.[20][21] Italian Lumière trainees produced short films documenting everyday life and comic strips in the late 1890s and early 1900s. The success of the short films was immediate. Titles of the time include, Arrivo del treno alla Stazione di Milano ("Arrival of the train at Milan station") (1896), La battaglia di neve ("The snow battle") (1896), and La gabbia dei matti ("The madmen's cage") (1896), all shot by Italo Pacchioni, who also invented a camera and projector, inspired by the cinematograph of Lumière brothers.[22] Although the general public were enthusiastic, initially the technology was snubbed by intellectuals and the press.[23] However, on 28 January 1897, prince Victor Emmanuel and princess Elena of Montenegro attended a screening at the Pitti Palace in Florence.[24] Interested in experimenting with the new medium, they were filmed in Florence and on the day of their wedding in at the Pantheon in Rome.[25][26]

1900s

[edit]

In the early 20th century, the phenomenon of itinerant cinemas developed throughout Italy.[27] The nascent Italian cinema, therefore, is still linked to the traditional shows of the commedia dell'arte or to those typical of circus folklore. Public screenings took place in the streets, in cafes or in variety theatres in the presence of a swindler who has the task of promoting and enriching the story.[28]

Between 1903 and 1909 the itinerant Italian cinema began assuming the characteristics of an authentic industry, led by four major organizations: Titanus (originally Monopolio Lombardo), the first Italian film production company;[29] the largest and among the most famous film houses in Italy,[30] founded by Gustavo Lombardo at Naples in 1904, Cines, based in Rome; and the Turin-based companies Ambrosio Film and Itala Film.[21] Other companies soon followed in Milan, and these early companies quickly attained a respectable production quality and were able to market their products both within Italy and abroad. Early Italian films typically consisted of adaptations of books or stage plays, such as Mario Caserini's Otello (1906) and Arturo Ambrosio's 1908 The Last Days of Pompeii. Also popular during this period were films about historical figures, for instance Ugo Falena's Lucrezia Borgia (1910).

In 1905, Cines inaugurated the genre of the historical film. One of the first of these films was La presa di Roma (1905), lasting 10 minutes, and made by Filoteo Alberini. The operator employs for the first-time actors of theatrical origin. The film, assimilating Manzoni's lesson of making historical fiction plausible, reconstructs the Capture of Rome on 20 September 1870. Dozens of characters from texts make their appearance on the big screen such as The Count of Monte Cristo and Giordano Bruno, among others.[21]

1910s

[edit]

In the 1910s, the Italian film industry developed rapidly.[31] In 1912, 569 films were produced in Turin, 420 in Rome and 120 in Milan.[32] Lost in the Dark (1914), a silent drama film directed by Nino Martoglio, documented life in the slums of Naples, and is considered a precursor to the Italian neorealism movement of the 1940s and 1950s.[12]

The archetypes of the historical blockbuster genre were The Last Days of Pompeii (1908), by Arturo Ambrosio and Luigi Maggi and Nero (1909), by Maggi and Arrigo Frusta.[33] Enrico Guazzoni's 1913 film Quo Vadis was one of the first blockbusters, using thousands of extras and a lavish set design.[34] The international success of the film marked the maturation of the genre and allowed Guazzoni to make increasingly spectacular films such as Antony and Cleopatra (1913) and Julius Caesar (1914). Giovanni Pastrone's 1914 film Cabiria was an even larger production; it was the first epic film ever made and it is considered the most famous Italian silent film.[31][35] Pastrone's plan to adapt the Bible with thousands of extras remained unfulfilled, but Antamoro's Christus (1916) and Guazzoni's The Crusaders (1918) were notable films with Christian subjects.

Many films were devoted to the investigative and mystery formats. The most prolific production houses in the 1910s were Cines, Ambrosio Film, Itala Film, Aquila Films, and Milano Films. Classic narrative elements of the silent proto-giallo (mystery, crime, investigation investigative and final twist) constitute the structural aspects of cinematic representation.

Between 1913 and 1920 there was the rise, development and decline of the phenomenon of cinematographic stardom, born with the release of Ma l'amor mio non muore (1913), by Mario Caserini. The film had great success with the public and encoded the aesthetics of female stardom. Within just a few years, Eleonora Duse, Pina Menichelli, Rina De Liguoro, Leda Gys, Hesperia, Vittoria Lepanto, Mary Cleo Tarlarini and Italia Almirante Manzini established themselves. Films such as Fior di male (1914), by Carmine Gallone, Il fuoco (1915), by Giovanni Pastrone, Rapsodia satanica (1917), by Nino Oxilia and Cenere (1917), by Febo Mari, changed the model away from naturalism in favor of melodramatic acting, pictorial gesture and theatrical pose, all favored by the extensive use of close-up.[36][37]

The most successful comedian in Italy was André Deed, better known in Italy as Cretinetti, star of comic short film for Itala Film. Its success paved the way for Marcel Fabre (Robinet), Ernesto Vaser (Fricot) and many others. Ferdinand Guillaume became famous with the stage name of Polidor.[38] Protagonists of Italian comedians never place themselves in open contrast with society or embody the desire for social revenge (as happens for example with Charlie Chaplin), but rather tried to integrate into a strongly desired world.[39]

Italian futurist cinema was the oldest movement of European avant-garde cinema.[10] Italian futurism, an artistic and social movement, impacted the Italian film industry from 1916 to 1919.[40] It influenced Russian Futurist[41] and German Expressionist cinema.[42] Its cultural importance was considerable and influenced all subsequent avant-gardes, as well as some authors of narrative cinema; its echo expands to the dreamlike visions of some films by Alfred Hitchcock.[43] Futurism emphasized dynamism, speed, technology, youth, violence, and objects such as the car, the airplane, and the industrial city. Its key figures were the Italians Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, Umberto Boccioni, Carlo Carrà, Fortunato Depero, Gino Severini, Giacomo Balla, and Luigi Russolo. It glorified modernity and aimed to liberate Italy from the weight of its past.[44]

The 1916 Manifesto of Futuristic Cinematography was signed by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, Armando Ginna, Bruno Corra, Giacomo Balla and others. To the Futurists, cinema was an ideal art form, being a fresh medium, and able to be manipulated by speed, special effects and editing.[45] Most of the futuristic-themed films of this period have been lost, but critics cite Thaïs (1917) by Anton Giulio Bragaglia as one of the most influential, serving as the main inspiration for German Expressionist cinema in the following decade. The Italian film industry struggled against rising foreign competition in the years following World War I.[12] Several major studios, among them Cines and Ambrosio, formed the Unione Cinematografica Italiana to coordinate a national strategy for film production. This effort was largely unsuccessful, however, due to a wide disconnect between production and exhibition; some movies were not released until several years after they were produced.[46]

1920s

[edit]

With the end of World War I, Italian cinema suffered from production disorganization, increased costs, technological backwardness, loss of foreign markets and inability to cope with Hollywood.[47] The first half of the 1920s marked a sharp decrease in production, from 350 films produced in 1921 to 60 in 1924.[48]

The main causes included the lack of a generational change with a production still dominated by filmmakers and producers of literary training, such that literature and theatre were still preferred media. Sentimental cinema for women spread, centered on figures on the margins of society. It was conservative cinema, tied to social rules upset by the war and in the process of dissolution throughout Europe. An example is A Woman's Story (1920) by Eugenio Perego, which is a 19th-century morality with melodramatic tones.[49]

A new genre developed in a realist setting, like work by the first female director of Italian cinema, Elvira Notari,[50] and Lost in the Dark (1914) by director Nino Martoglio.[51]

The revival of Italian cinema took place at the end of the 1920s. The productions were larger in scale and addressed peasant topics, hitherto practically absent in Italian cinema. Sun (1929) by Alessandro Blasetti reflects influence from Soviet and German avant-gardes.[52] The movement was above all an emancipation from literary models and a turn to more popular taste.

1930s

[edit]

The sound cinema arrived in Italy in 1930, three years after the release of The Jazz Singer (1927), and immediately led to a debate on the validity of spoken cinema and its relationship with the theatre. Some directors enthusiastically face the new challenge. The advent of talkies led to stricter censorship by the Fascist government.[12]

The first Italian talking picture was The Song of Love (1930) by Gennaro Righelli, which was a great success with the public. Alessandro Blasetti also experimented with the use of an optical track for sound in the film Resurrection (1931), shot before The Song of Love but released a few months later.[53] Similar to Righelli's film is What Scoundrels Men Are! (1932) by Mario Camerini, which has the merit of making Vittorio De Sica debut on the screens. Historical films such as Blasetti's 1860 (1934) and Carmine Gallone's Scipio Africanus: The Defeat of Hannibal (1937) were also popular during this period.[12]

With the transition to sound cinema, most of the Italian silent film actors, still linked to theatrical stylization, find themselves disqualified. The era of divas, dandies and strongmen, who barely survived the 1920s, is definitely over. Even if some performers will move on to directing or producing, the arrival of sound favors the generational change and the consequent modernization of the structures.

Italian-born director Frank Capra received three Academy Awards for Best Director for the films It Happened One Night (1934, the first Big Five winner at the Academy Awards), Mr. Deeds Goes to Town (1936) and You Can't Take It with You (1938).[54]

In 1932, the Venice Film Festival was established. It is today the world's oldest film festival. Alongside the Cannes and Berlin Festivals, it has shaped film history.[55][56][57][58]

Cinecittà

[edit]

In 1934, the Fascist Italian government created the General Directorate for Cinema (Direzione Generale per la Cinematografia) and appointed Luigi Freddi its director. A town was developed southeast of Rome devoted exclusively to cinema and dubbed the Cinecittà ("Cinema City"). The project was clearly aware of film's value as a propaganda tool.[60][61][62]

Mussolini himself inaugurated the studios on 28 April 1937.[63] Films such as Scipio Africanus (1937) and The Iron Crown (1941) showcased the technological capacities of the studios. Seven thousand people were involved in filming a battle scene from Scipio Africanus, and live elephants were brought in as a part of the re-enactment of the Battle of Zama.[64] The Cinecittà studios were Europe's most advanced production facilities and greatly boosted the technical quality of Italian films.[12] Many films are still shot entirely in Cinecittà.[65]

Telefoni Bianchi

[edit]

During the 1930s, light comedies known as Telefoni Bianchi ("white telephones") were predominant in Italian cinema.[12] These films featured lavish set designs and promoted conservative values, which made them popular with censors. Numerous screenwriters (including Cesare Zavattini and Sergio Amidei) and set designers (Guido Fiorini, Gino Carlo Sensani and Antonio Valente) established themselves by working on Telefoni films.[66][67]

The first film of the genre Telefoni Bianchi was The Private Secretary (1931), by Goffredo Alessandrini.[68] Others include Schoolgirl Diary (1941) and A Thousand Lire a Month (1939).

Fascist propaganda

[edit]

One of the major films of Italian fascist propaganda cinema was Black Shirt (1933), by Giovacchino Forzano, made for the 10th anniversary of the March on Rome. With political consolidation, government authorities required the film industry to focus more on Italy's history and culture. This trend reached its peak just before the war with Cavalry (1936), by Goffredo Alessandrini, evoking the nobility of the Savoy fighters from the Risorgimento as anticipations of Fascist squads. Condottieri (1937) by Luis Trenker, tells the story of Giovanni delle Bande Nere as a sort of parallel with Benito Mussolini. Scipio Africanus: The Defeat of Hannibal (1937) was one of the greatest financial efforts of the time: it implicitly compares the Roman Empire to the Fascist Empire.[69]

The invasion of Ethiopia gave Italian directors the opportunity to extend the horizons of the settings.[70] Both The Great Appeal (1936) and Lo squadrone bianco (1936) exalt imperialism. The Spanish Civil War is described most spectacularly in The Siege of the Alcazar (1940).[69]

1940s

[edit]Propaganda

[edit]With Italy's participation in World War II, the fascist regime further strengthens its control over production and requires a more decisive commitment to propaganda. In addition to the now canonical documentaries, short films and newsreels, there is also an increase in feature films in praise of Italian war efforts. Among the most representative are Bengasi (1942) by Genina, Gente dell'aria (1943) by Esodo Pratelli, The Three Pilots (1942) by Mario Mattoli (based on a screenplay by Vittorio Mussolini), Il treno crociato (1943) by Carlo Campogalliani, Harlem (1943) by Carmine Gallone and Men of the Mountain (1943) by Aldo Vergano under the supervision of Blasetti. Uomini sul fondo (1941) by Francesco De Robertis is also notable due to its almost documentary approach.[71]

The most successful film of the period is We the Living (1942) by Goffredo Alessandrini, made as a single film, but then distributed in two parts due to its excessive length. Referable to the genre of anti-communist drama, this somber melodrama (set in the Soviet Union) is inspired by the novel of the same name by the writer Ayn Rand which exalts philosophical individualism.[72]

Among the propaganda directors, there is also Roberto Rossellini, author of a trilogy composed of The White Ship (1941), A Pilot Returns (1942) and The Man with a Cross (1943).[72]

Calligrafismo

[edit]

The Calligrafismo style contrasts American style comedies because of its formalistic, expressive manner and its interest in contemporary literary texts taken from Italian realists.[73] The best-known exponent of this genre is Mario Soldati, whose characters often show psychological strength and master internal conflicts. Another important example of a calligraphic film is The Betrothed (1941), which became the most popular feature film in 1941 and 1942.[74]

Animation

[edit]

The pioneer of the Italian cartoon was Francesco Guido, better known as Gibba. Immediately after World War II, he produced the first animated medium-length Italian film.[75] In 1949, The Dynamite Brothers followed. It was released in a package with La Rosa di Bagdad (1949).[75]

Neorealism

[edit]

Neorealist films typically dealt with the working class and were shot on location. There were several important precursors to the movement, like What Scoundrels Men Are! (1932) and Four Steps in the Clouds (1942).[77]

They were not successful in Fascist-controlled parts of Italy, but after the war Italian neorealism was influential at the international level. Still, neorealist films made up only a small percentage of Italian films produced during this period. Postwar Italian moviegoers preferred escapist comedies starring actors like Totò and Alberto Sordi.[77]

Neorealist works such as Roberto Rossellini's trilogy Rome, Open City (1945), Paisà (1946), and Germany, Year Zero (1948), with professional actors such as Anna Magnani and a number of non-professional actors, attempted to describe the difficult economic and moral conditions of postwar Italy and the changes in public mentality in everyday life. Visconti's The Earth Trembles (1948) was shot on location in a Sicilian fishing village and used locals as actors.

Poetry and cruelty of life were harmonically combined in the works that Vittorio De Sica wrote and directed together with screenwriter Cesare Zavattini: among them were Shoeshine (1946) and The Bicycle Thief (1948). The 1952 film Umberto D., about a beggar with his dog, is perhaps De Sica's masterpiece.[78] It embodies both a conservative and a progressive view of post-war society.[78]

-

Ossessione (1943), by Luchino Visconti.

-

A still shot from Rome, Open City (1945), by Roberto Rossellini.

1950s

[edit]

The mid-1950s saw more and more Italian films tackling existential topics; they were often more introspective than descriptive.[80] Michelangelo Antonioni was the first to establish himself and he became a reference for contemporary cinema.[81] His first work, Story of a Love Affair (1950), breaks with neorealism.[81] He investigates the world of the Italian bourgeoisie with a critical eye in films like I Vinti (1952), The Lady Without Camelias (1953) and Le Amiche (1955). Federico Fellini's La Strada (1954) and Pier Paolo Pasolini's first film, Accattone (1961) are also considered neorealist.[77] This period is also referred to as "The Golden Age" of Italian cinema.

In commercial productions, the phenomenon of Totò was born. This Neapolitan actor is acclaimed as the major Italian comedian. His films (often with Aldo Fabrizi, Peppino De Filippo and almost always with Mario Castellani) expressed a sort of neorealistic satire.[82] Totò is one of the symbols of the cinema of Naples.[83]

Pink neorealism

[edit]

Although Umberto D. is considered the end of the neorealist period, subsequent works turned toward lighter, sweetened and mildly optimistic atmospheres, more coherent with the improving conditions of Italy just before the economic boom; this genre became known as pink neorealism.

Notable films of pink neorealism, which combine popular comedy and realist motifs, are Pane, amore e fantasia (1953) by Luigi Comencini and Poveri ma belli (1957) by Dino Risi, both works are in perfect harmony with the evolution of the Italian costume.[84] The large influx at the box office from the two films remained almost unchanged in the sequels Bread, Love and Jealousy (1954), Scandal in Sorrento (1955) and Pretty But Poor (1957), also directed by Luigi Comencini and Dino Risi.

Actresses who excelled in this genre included international celebrities such as Sophia Loren and Gina Lollobrigida.

Don Camillo and Peppone

[edit]

A series of black-and-white films based on the Don Camillo and Peppone characters created by journalist Giovannino Guareschi were made between 1952 and 1965. These were French-Italian coproductions, and starred Fernandel as the Italian priest Don Camillo and Gino Cervi as Giuseppe 'Peppone' Bottazzi, the Communist mayor of their rural town. The movies were hugely successful: In 1952, Little World of Don Camillo was the highest-grossing film in both Italy and France,[85] while The Return of Don Camillo was the second most popular film of 1953 at the Italian and French box office.[86]

Hollywood on the Tiber

[edit]

Hollywood on the Tiber describes the period in the 1950s and 1960s when Rome emerged as a major location for international filmmaking.[59] These movies were made in English for global release and many enjoyed widespread popularity. Large-budget films shot at Cinecittà include Quo Vadis (1951), Roman Holiday (1953), Ben-Hur (1959), and Cleopatra (1963).[87]

-

Quo Vadis by Mervyn LeRoy (1951)

Sword-and-sandal (a.k.a. Peplum)

[edit]

Sword-and-sandal is a subgenre of historical, mythological, or biblical epics. These films attempted to emulate the big-budget Hollywood historical epics of the time.[88] With the release of 1958's Hercules, starring American bodybuilder Steve Reeves, the genre was established with both European and American audiences. New directors such as Sergio Leone and Mario Bava broke into film with these films. Most sword-and-sandal films were in colour, a novelty.

1960s

[edit]

Federico Fellini dominated this decade. He won the Palme d'Or for La Dolce Vita, was nominated for more Academy Awards than any director in the history of the academy. His other well-known films include La Strada (1954), Nights of Cabiria (1957), Satyricon (1969), and Fellini's Casanova (1976).[90]

Franco and Ciccio were a comedy duo formed by Italian actors Franco Franchi and Ciccio Ingrassia, particularly popular in the 1960s and 1970s. Together, they appeared in 116 films, usually as the main characters.[91]

Musicarelli

[edit]

Musicarello (pl. musicarelli) is a film subgenre which emerged in Italy, and which is characterized by the presence in main roles of young singers, already famous among their peers, and their new record album. The genre began in the late 1950s and had its peak of production in the 1960s.[92]

The film which started the genre is considered to be I ragazzi del Juke-Box by Lucio Fulci (1959).[93] The musicarelli were inspired by two American musicals, in particular Jailhouse Rock by Richard Thorpe (1957) and earlier Love Me Tender by Robert D. Webb (1956), both starring Elvis Presley.[94][95][96]

At the heart of the musicarello is a hit song, or a song that the producers hoped would become a hit, that usually shares its title with the film itself and sometimes has lyrics depicting a part of the plot.[97] In the films there are almost always tender and chaste love stories accompanied by the desire to have fun and dance without thoughts.[98] Musicarelli reflect the desire and need for emancipation of young Italians, highlighting some generational frictions.[94]

With the arrival of the 1968 student protests the genre started to decline, because the generational revolt became explicitly political and at the same time there was no longer music equally directed to the whole youth audience.[99] For some time the duo Al Bano and Romina Power continued to enjoy success in musicarello films, but their films (like their songs) were a return to the traditional melody and to the musical films of the previous decades.[99]

Commedia all'Italiana

[edit]

Commedia all'italiana ("Comedy in the Italian way") was a genre that developed from the 1950s to the 1970s. It derives its name from the title of Pietro Germi's Divorce Italian Style, 1961.[100] The term indicates a period in which the Italian film industry was producing many successful comedies about controversial social issues like sexual behavior, divorce, contraception, and the traditional religious influence of the Catholic Church.[101]

An entire generation of great actors contributed to the films: Ugo Tognazzi, Marcello Mastroianni, and Nino Manfredi are among them.[102] Dino Risi garnered fame for directing Una vita difficile (A Difficult Life), then Il Sorpasso (The Easy Life), now a cult-movie. Many others followed.

Spaghetti Western

[edit]

On the heels of the sword-and-sandal craze, a related genre, the Spaghetti Western arose. These films differed from traditional westerns because they were filmed in Europe, produced and directed by Italians.[105] The most director was Sergio Leone, credited as the inventor of the genre.[106][107] His A Fistful of Dollars was an unauthorized remake of the Japanese film Yojimbo by Akira Kurosawa. The Good, the Bad and the Ugly featured Clint Eastwood and notorious music by Ennio Morricone.

Giallo

[edit]During the 1960s and 1970s, Italian filmmakers Mario Bava, Riccardo Freda, Antonio Margheriti and Dario Argento developed giallo (plural gialli, from giallo, Italian for "yellow") horror films that become classics and influenced the genre in other countries. Representative films include: The Girl Who Knew Too Much (1963), Castle of Blood (1964), The Bird with the Crystal Plumage (1970), Twitch of the Death Nerve (1971), Deep Red (1975) and Suspiria (1977).

Giallo is a genre of mystery fiction and thrillers and often contains slasher, crime fiction, psychological thriller, psychological horror, sexploitation, and, less frequently, supernatural horror elements.[112] Giallo developed in the mid-to-late 1960s, peaked in popularity during the 1970s, and subsequently declined in commercial mainstream filmmaking over the next few decades, though examples continue to be produced. It was a predecessor to, and had significant influence on, the later American slasher film genre.[113]

Giallo usually blends the atmosphere and suspense of thriller fiction with elements of horror fiction (such as slasher violence) and eroticism (similar to the French fantastique genre), and often involves a mysterious killer whose identity is not revealed until the final act of the film. Most critics agree that the giallo represents a distinct category with unique features,[114] but there is some disagreement on what exactly defines a giallo film.[115]

Giallo films are generally gruesome murder-mystery thrillers that combine the suspense elements of detective fiction with scenes of shocking horror. The archetypal giallo plot involves a mysterious, black-gloved killer who stalks and kills women.[117] While most gialli involve a human killer, some also feature a supernatural element.[118] The protagonists are often unconnected to the murders before they begin; they get drawn in as witnesses.[118]

-

A scene from Blood and Black Lace by Mario Bava (1964)

Social and political cinema

[edit]The auteur cinema of the 1960s included an authorial vision that was less surreal and existential and more political; it sought to denounce corruption and malfeasance,[119] both in politics and industry.

In 1962, Francesco Rosi[120] inaugurated an investigation film project retracing, through a series of long flashbacks, the life of a Sicilian criminal, the title figure in Salvatore Giuliano. The following year he directed Rod Steiger in Hands over the City (1963); this film was a denuciation of corruption in real estate and construction companies in Naples. The film was awarded the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival.

1970s

[edit]

In the 1970s the work done by the director Lina Wertmüller was influential. Together with actors Giancarlo Giannini and Mariangela Melato, she made several films and with Seven Beauties (1976), she obtained four nominations for the Academy Awards. That made her the first woman to be nominated for best director.[121]

Ettore Scola made his directorial debut in 1964 with Let's Talk About Women. In 1974, he directed his best-known film, We All Loved Each Other So Much. Other films include Down and Dirty (1976) starring Nino Manfredi, and A Special Day (1977) starring Sophia Loren and Marcello Mastroianni.[122] In the 1970s, after many animated documentaries, Gibba returned to the feature film with the erotic Il nano e la strega (1973) and Il racconto della giungla (1974). Emanuele Luzzati contributed what is considered[citation needed] one of the masterpieces of Italian animation: Il flauto magico ("The Magic Flute", 1976), based on Mozart's opera.

After many satirical short films (centred on the popular figure of "Signor Rossi"), Bruno Bozzetto returned to the feature film with Allegro Non Troppo (1977). Inspired by Disney's Fantasia, it is a mixed media film, in which animated episodes are combined with classical music pieces. Another notable illustrator was Pino Zac who in 1971 shot (again with mixed technique) The Nonexistent Knight, based on the novel of the same name by Italo Calvino.

One of Francesco Rosi's most famous films of denunciation is The Mattei Affair (1972), a documentary into the mysterious disappearance of Enrico Mattei. The film won the Palme d'Or at the Cannes Film Festival. It became (together with Illustrious Corpses (1976)) a model for similar denunciation films produced both in Italy and abroad. Famous films of denunciation by Elio Petri are The Working Class Goes to Heaven (1971), a corrosive denunciation of life in the factory (winner of the Palme d'Or at Cannes) and Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion (1970). The latter (accompanied by a soundtrack by Ennio Morricone) is a dry psychoanalytic thriller centred on the aberrations of power.[123] The film won the Academy Award for Best International Feature Film the following year.

Poliziotteschi

[edit]

Poliziotteschi films constitute a subgenre of crime and action films that emerged in Italy in the late 1960s and reached the height of their popularity in the 1970s. They are also known as polizieschi all'italiana, Euro-crime, Italo-crime, spaghetti crime films', or simply Italian crime films.

Influenced by both 1970s French crime films and gritty 1960s and 1970s American cop films and vigilante films,[124] poliziotteschi films were made amidst an atmosphere of socio-political turmoil in Italy and increasing Italian crime rates.

The films generally featured graphic and brutal violence, organized crime, car chases, vigilantism, heists, gunfights, and corruption. The protagonists were generally tough working-class loners, willing to act outside a corrupt or overly bureaucratic system.[125] Notable international actors who acted in this genre of films include Alain Delon, Henry Silva, Fred Williamson, Charles Bronson, Tomas Milian and others.

Bud Spencer and Terence Hill

[edit]

Also considered Spaghetti Westerns is a film genre which combined traditional western ambience with a Commedia all'italiana-type comedy. Films in this genre included They Call Me Trinity (1970) and Trinity Is Still My Name (1971), both by Enzo Barboni, which featured Bud Spencer and Terence Hill, the stage names of Carlo Pedersoli and Mario Girotti.

Terence Hill and Bud Spencer made numerous films together.[126] Most of their early films were Spaghetti Westerns, beginning with God Forgives... I Don't! (1967), the first part of a trilogy, followed by Ace High (1968) and Boot Hill (1969), but they also starred in comedies such as ... All the Way, Boys! (1972) and Watch Out, We're Mad! (1974).

The next films shot by the couple of actors, almost all comedies, were Two Missionaries (1974), Crime Busters (1977), Odds and Evens (1978), I'm for the Hippopotamus (1979), Who Finds a Friend Finds a Treasure (1981), Go for It (1983), Double Trouble (1984), Miami Supercops (1985) and Troublemakers (1994).

Commedia sexy all'italiana

[edit]

Commedia sexy all'italiana is characterized typically by female nudity and comedy, and by the minimal weight given to social criticism that was the basic ingredient of the main commedia all'italiana genre.[127] Stories are often set in affluent environments such as wealthy households. It is closely connected to the sexual revolution. For the first time, films with female nudity could be watched at the cinema. Pornography and scenes of explicit sex were still forbidden in Italian cinemas, but partial nudity was somewhat tolerated. The genre has been described as a cross between bawdy comedy and humorous erotic film with ample slapstick elements which follow more or less clichéd storylines.

During this time, commedia sexy all'italiana films, described by the film critics of the time as not artistic or "trash films", were very popular in Italy. Today they are widely re-evaluated and have become cult movies. They also allowed the producers of Italian cinema to have enough revenue to produce successful artistic films. These comedy films were of little artistic value and reached their popularity by confronting Italian social taboos, most notably in the sexual sphere. Actors such as Lando Buzzanca, Lino Banfi, Renzo Montagnani, Alvaro Vitali, Gloria Guida, Barbara Bouchet and Edwige Fenech owe much of their popularity to these films.

Fantozzi

[edit]

The films starring Ugo Fantozzi, a character invented by Paolo Villaggio for his television sketches and newspaper short stories, also fell within the comic satirical comedy genre.[128] Although Villaggio's movies tend to bridge comedy with a more elevated social satire, this character had a significant impact on Italian society, to such a degree that the adjective fantozziano entered the lexicon.[129] Ugo Fantozzi represents the archetype of the average Italian of the 1970s, middle-class with a simple lifestyle with the anxieties common to an entire class of workers,[130] being re-evaluated by critics.[131] Of the many films telling of Fantozzi's misadventures, the most notable and famous were Fantozzi (1975) and Il secondo tragico Fantozzi (1976), both directed by Luciano Salce.

Sceneggiata

[edit]

The sceneggiata (pl. sceneggiate) or sceneggiata napoletana is a form of musical drama typical of Naples. Beginning as a form of musical theatre after World War I, it was also adapted for cinema; sceneggiata films became especially popular in the 1970s, and contributed to the genre becoming more widely known outside Naples.[132] The most famous actors who played dramas were Mario Merola, Mario Trevi, and Nino D'Angelo.[133]

The sceneggiata can be described as a "musical soap opera", where action and dialogue are interspersed with Neapolitan songs. Plots revolve around melodramatic themes drawing from the Neapolitan culture and tradition, including passion, jealousy, betrayal, personal deceit and treachery, honour, vengeance, and life in the world of petty crime. Songs and dialogue were originally in Neapolitan dialect, although, especially in film production, Italian has sometimes been preferred, to reach a larger audience.

Sgarro alla camorra (i.e. "Offence to the Camorra", 1973), written and directed by Ettore Maria Fizzarotti and starring Mario Merola at his film debut, is regarded as the first sceneggiata film and as a prototype for the genre.[134][135]

1980s

[edit]

The 1980s was a period of decline for Italian filmmaking. In 1985, only 80 films were produced (the least since the postwar period)[137] and the total audience decreased from 525 million in 1970 to 123 million.[138] The era of producers ended; Carlo Ponti and Dino De Laurentiis worked abroad, and Goffredo Lombardo and Franco Cristaldi were no longer key figures. The crisis affected the Italian genre cinema above all, which, by virtue of the success of commercial television, was deprived of most of its audience.[139] As a result, cinemas began showing mainly Hollywood films, which steadily took over, while many other cinemas closed.

Among the major artistic films of this era were La città delle donne, E la nave va, Ginger and Fred by Fellini, L'albero degli zoccoli by Ermanno Olmi (winner of the Palme d'Or at the Cannes Film Festival), La notte di San Lorenzo by Paolo and Vittorio Taviani, Antonioni's Identificazione di una donna, and Bianca and La messa è finita by Nanni Moretti. Non ci resta che piangere, directed by and starring both Roberto Benigni and Massimo Troisi, is a cult movie in Italy.

Carlo Verdone, actor, screenwriter and film director, is best known for his comedic roles in Italian classics, which he also wrote and directed. His career was jumpstarted by his first three successes, Un sacco bello (1980), Bianco, rosso e Verdone (1981) and Borotalco (1982). Francesco Nuti began his professional career as an actor in the late 1970s, when he formed the cabaret group Giancattivi together with Alessandro Benvenuti and Athina Cenci. Starting in 1985, he began to direct his movies, scoring an immediate success with the films Casablanca, Casablanca and All the Fault of Paradise (1985), Stregati (1987), Caruso Pascoski, Son of a Pole (1988), Willy Signori e vengo da lontano (1990) and Women in Skirts (1991).

The cinepanettoni (singular: cinepanettone) are a series of farcical comedy films, one or two of which are scheduled for release annually in Italy during the Christmas period. The films were originally produced by Aurelio De Laurentiis' Filmauro studio.[140] For the majority of critics the "Commedia all'italiana" waned from the beginning of the 1980s, giving way to an "Commedia italiana" ("Italian comedy").[141]

1990s

[edit]

The economic crisis that emerged in the 1980s began to ease over the next decade.[142] Nonetheless, the 1992–93 and 1993–94 seasons marked an all-time low in the number of films made, in the national market share (15 per cent), in the total number of viewers (under 90 million per year) and in the number of cinemas.[143] The effect of this industrial contraction was the disappearance of Italian genre cinema in the middle of the decade, as it was no longer able to compete with the contemporary big Hollywood blockbusters (mainly due to the enormous budget differences).

The most noted film of the period is Nuovo Cinema Paradiso, for which Giuseppe Tornatore won a 1989 Oscar (awarded in 1990) for Best Foreign Language Film. This award was followed when Gabriele Salvatores's Mediterraneo won the same prize in 1991.

Il Postino: The Postman (1994), directed by the British Michael Radford and starring Massimo Troisi, received five nominations at the Academy Awards, including Best Picture and Best Actor for Troisi, and won for Best Original Score. In 1998 Roberto Benigni won three Oscars for his movie Life Is Beautiful (La vita è bella).

Leonardo Pieraccioni made his directorial debut with The Graduates (1995).[144] In 1996 he directed his breakthrough film The Cyclone, which grossed Lire 75 billion at the box office.[145][146] In the 1990s, Italian animation entered a new phase of production due to the Turin Lanterna Magica studio which in 1996, under the direction of Enzo D'Alò, created the Christmas fairy tale La freccia azzurra, based on a short story by Gianni Rodari. The film was a success and paved the way for other feature films. In fact, in 1998, Lucky and Zorba based on a novel by Luis Sepúlveda was distributed, which attracted the favor of the public.[147]

2000s

[edit]The Italian film industry regained stability and critical recognition. In 1995, 93 films were produced,[148] while in 2005, 274 films were made.[149] In 2006, the national market share reached 31 per cent.[150] In 2001, Nanni Moretti's film The Son's Room (La stanza del figlio) received the Palme d'Or at the Cannes Film Festival. Other noteworthy recent Italian films include: Jona che visse nella balena directed by Roberto Faenza, Il grande cocomero by Francesca Archibugi, The Profession of Arms (Il mestiere delle armi) by Olmi, L'ora di religione by Marco Bellocchio, Il ladro di bambini, Lamerica, The Keys to the House (Le chiavi di casa) by Gianni Amelio, I'm Not Scared (Io non-ho paura) by Gabriele Salvatores, Le Fate Ignoranti, Facing Windows (La finestra di fronte) by Ferzan Özpetek, Good Morning, Night (Buongiorno, notte) by Marco Bellocchio, The Best of Youth (La meglio gioventù) by Marco Tullio Giordana, The Beast in the Heart (La bestia nel cuore) by Cristina Comencini.

In 2008 Paolo Sorrentino's Il Divo, a biographical film based on the life of Giulio Andreotti, won the Jury prize and Gomorra, a crime drama film, directed by Matteo Garrone won the Gran Prix at the Cannes Film Festival. The director Enzo d'Alò produced other films in the following years such as Momo (2001) and Opopomoz (2003). The Turin studio distributed on its behalf the films Aida of the Trees (2001) and Totò Sapore e la magica storia della pizza (2003), accompanied by a good response at the box office. In 2003, the first entirely Italian animated film in computer graphics was released: L'apetta Giulia and Signora Vita, directed by Paolo Modugno.[151]

2010s

[edit]

Paolo Sorrentino's The Great Beauty (La Grande Bellezza) won the 2014 Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film. In 2010, the first Italian animated film in 3D was made, directed by Iginio Straffi, entitled Winx Club 3D: Magical Adventure, based on the homonymous series; in the meantime Enzo D'Alò returned to theatres, presenting his Pinocchio (2012). Cinderella the Cat (2017), taken from the text Pentamerone by Giambattista Basile, won two David di Donatello's, one of which was for special effects, becoming the first animated film to be nominated, and win, in this category.

The two highest-grossing Italian films in Italy have both been directed by Gennaro Nunziante and starred Checco Zalone: Sole a catinelle (2013) with €51.8 million, and Quo Vado? (2016) with €65.3 million.[153][154] They Call Me Jeeg, a 2016 critically acclaimed superhero film directed by Gabriele Mainetti and starring Claudio Santamaria, won eight David di Donatello, two Nastro d'Argento, and a Globo d'oro.

Gianfranco Rosi's documentary film Fire at Sea (2016) won the Golden Bear at the 66th Berlin International Film Festival.

Other successful 2010s Italian films include: Vincere and The Traitor by Marco Bellocchio, The First Beautiful Thing (La prima cosa bella), Human Capital (Il capitale umano) and Like Crazy (La pazza gioia) by Paolo Virzì, We Have a Pope (Habemus Papam) and Mia Madre by Nanni Moretti, Caesar Must Die (Cesare deve morire) by Paolo and Vittorio Taviani, Don't Be Bad (Non essere cattivo) by Claudio Caligari, Romanzo Criminale by Michele Placido (that spawned a TV series, Romanzo criminale - La serie), Youth (La giovinezza) by Paolo Sorrentino, Suburra by Stefano Sollima, Perfect Strangers (Perfetti sconosciuti) by Paolo Genovese, Mediterranea and A Ciambra by Jonas Carpignano, Italian Race (Veloce come il vento) and The First King: Birth of an Empire (Il primo re) by Matteo Rovere, and Tale of Tales (Il racconto dei racconti), Dogman and Pinocchio by Matteo Garrone.

Call Me by Your Name (2017), the final installment in Luca Guadagnino's thematic Desire trilogy, following I Am Love (2009) and A Bigger Splash (2015), received widespread acclaim and numerous accolades, including the Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay and the nomination for Best Picture in 2018.

Perfect Strangers by Paolo Genovese was included in the Guinness World Records as it became the most remade film in cinema history, with a total of 18 versions.[152]

2020s

[edit]Successful 2020s Italian films include: The Life Ahead by Edoardo Ponti, Hidden Away by Giorgio Diritti, Bad Tales by Damiano and Fabio D'Innocenzo, The Predators by Pietro Castellitto, Padrenostro by Claudio Noce, Notturno by Gianfranco Rosi, The King of Laughter by Mario Martone, A Chiara by Jonas Carpignano, Freaks Out by Gabriele Mainetti, The Hand of God by Paolo Sorrentino, Nostalgia by Mario Martone, Dry by Paolo Virzì, The Hanging Sun by Francesco Carrozzini, Bones and All by Luca Guadagnino, L'immensità by Emanuele Crialese, Robbing Mussolini by Renato De Maria, Adagio by Stefano Sollima, There's Still Tomorrow by Paola Cortellesi, Last Night of Amore by Andrea Di Stefano, The First Day of My Life by Paolo Genovese, Thank You Guys by Riccardo Milani, Io capitano by Matteo Garrone, A Brighter Tomorrow by Nanni Moretti and Comandante by Edoardo De Angelis.

100 Italian films to be saved

[edit]

The list of the 100 Italian films to be saved (Italian: 100 film italiani da salvare) was created with the aim to report "100 films that have changed the collective memory of the country between 1942 and 1978". The project was established in 2008 by the Venice Days festival section of the 65th Venice International Film Festival, in collaboration with Cinecittà Holding and with the support of the Ministry of Cultural Heritage.

The list was edited by Fabio Ferzetti,[155] film critic of the newspaper Il Messaggero, in collaboration with film director Gianni Amelio and the writers and film critics Gian Piero Brunetta, Giovanni De Luna, Gianluca Farinelli, Giovanna Grignaffini, Paolo Mereghetti, Morando Morandini, Domenico Starnone and Sergio Toffetti.[156][157]

Cinematheques

[edit]Cineteca Nazionale is a film archive located in Rome. Founded in 1949, it includes 80,000 films on file, 600,000 photographs, 50,000 posters and the collection of the Italian Association for the History of Cinema Research (AIRSC).[158] It arose from the archival heritage of the Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia, which in 1943, had been removed by the Nazi occupiers.[159][160][161] Cineteca Italiana is a private film archive located in Milan. Established in 1947, and as a foundation in 1996, the Cineteca Italiana houses over 20,000 films and more than 100,000 photographs from the history of Italian and international cinema.[162] Cineteca di Bologna is a film archive in Bologna. It was founded in 1962.[163]

Museums

[edit]

The National Museum of Cinema in Turin is a motion picture museum inside the Mole Antonelliana tower. It is operated by the Maria Adriana Prolo Foundation, and the core of its collection is the result of the work of the historian and collector Maria Adriana Prolo. It was housed in the Palazzo Chiablese. In 2008, with 532,196 visitors, it ranked 13th among the most visited Italian museums.[164] The museum houses pre-cinematographic optical devices such as magic lanterns, earlier and current film technologies, stage items from early Italian movies and other memorabilia. Along the exhibition path of about 35,000 square feet (3,200 m2) on five levels are areas devoted to the different kinds of film crew, and in the main hall, fitted in the temple hall of the Mole, a series of chapels representing several film genres.[165]

The Museum of Precinema is a museum in the Palazzo Angeli, Prato della Valle, Padua, related to the history of precinema, or precursors of film. It was created in 1998 to display the Minici Zotti Collection, in collaboration with the Commune of Padova.

The Cinema Museum of Rome is located in Cinecittà. The collections consist of movie posters and playbills, cine cameras, projectors, magic lanterns, stage costumes and the patent of Filoteo Alberini's "kinetograph".[166] The Milan Cinema Museum, managed by the Cineteca Italiana, is divided into three sections, the precinema, animation cinema and "Milan as a film set", as well as multimedia and interactive stations.[167]

The Catania Cinema Museum exhibits documents concerning cinema, its techniques and its history, particularly the link between cinema and Sicily.[168] The Cinema Museum of Syracuse collects more than 10,000 exhibits on display in 12 rooms.[169]

Italian Academy Award winners

[edit]

After the United States and the United Kingdom, Italy has the most Academy Awards wins.

Italy is the most awarded country at the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film, with 14 awards won, 3 Special Awards and 31 nominations. Winners with the year of the ceremony:

- Shoeshine (1947), by Vittorio De Sica (Honorary Award)

- Bicycle Thieves (1949), by Vittorio De Sica (Honorary Award)

- The Walls of Malapaga (1950), by René Clément (Honorary Award)

- La Strada (1956), by Federico Fellini

- Nights of Cabiria (1957), by Federico Fellini

- 8½ (1963), by Federico Fellini

- Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow (1964), by Vittorio De Sica

- Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion (1970), by Elio Petri

- The Garden of the Finzi-Continis (1971), by Vittorio De Sica

- Amarcord (1973), by Federico Fellini

- Cinema Paradiso (1989), by Giuseppe Tornatore

- Mediterraneo (1992), by Gabriele Salvatores

- Life Is Beautiful (1998), by Roberto Benigni

- The Great Beauty (2013), by Paolo Sorrentino

In 1961, Sophia Loren won the Academy Award for Best Actress for her role in Vittorio De Sica's Two Women. She was the first actress to win an Academy Award for a performance in any foreign language, and the second Italian leading lady Oscar-winner, after Anna Magnani for The Rose Tattoo. In 1998, Roberto Benigni was the first Italian actor to win the Best Actor for Life Is Beautiful.

Italian-born filmmaker Frank Capra won three times at the Academy Award for Best Director, for It Happened One Night, Mr. Deeds Goes to Town and You Can't Take It with You. Bernardo Bertolucci won the award for The Last Emperor, and also Best Adapted Screenplay for the same movie.

Ennio De Concini, Alfredo Giannetti and Pietro Germi won the award for Best Original Screenplay for Divorce Italian Style. The Academy Award for Best Film Editing was won by Gabriella Cristiani for The Last Emperor and by Pietro Scalia for JFK and Black Hawk Down.

The award for Best Original Score was won by Nino Rota for The Godfather Part II; Giorgio Moroder for Midnight Express; Nicola Piovani for Life is Beautiful; Dario Marianelli for Atonement; and Ennio Morricone for The Hateful Eight. Giorgio Moroder also won the award for Best Original Song for Flashdance and Top Gun.

The Italian winners at the Academy Award for Best Production Design are Dario Simoni for Lawrence of Arabia and Doctor Zhivago; Elio Altramura and Gianni Quaranta for A Room with a View; Bruno Cesari, Osvaldo Desideri and Ferdinando Scarfiotti for The Last Emperor; Luciana Arrighi for Howards End; and Dante Ferretti and Francesca Lo Schiavo for The Aviator, Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street and Hugo.

The winners at the Academy Award for Best Cinematography are: Tony Gaudio for Anthony Adverse; Pasqualino De Santis for Romeo and Juliet; Vittorio Storaro for Apocalypse Now, Reds and The Last Emperor; and Mauro Fiore for Avatar.

The winners at the Academy Award for Best Costume Design are Piero Gherardi for La dolce vita and 8½; Vittorio Nino Novarese for Cleopatra and Cromwell; Danilo Donati for The Taming of the Shrew, Romeo and Juliet, and Fellini's Casanova; Franca Squarciapino for Cyrano de Bergerac; Gabriella Pescucci for The Age of Innocence; and Milena Canonero for Barry Lyndon, Chariots of Fire, Marie Antoinette and The Grand Budapest Hotel.

Special effects artist Carlo Rambaldi won three Oscars: one Special Achievement Academy Award for Best Visual Effects for King Kong[172] and two Academy Awards for Best Visual Effects for Alien[173] (1979) and E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial.[174] The Academy Award for Best Makeup and Hairstyling was won by Manlio Rocchetti for Driving Miss Daisy, and Alessandro Bertolazzi and Giorgio Gregorini for Suicide Squad.

Sophia Loren, Federico Fellini, Michelangelo Antonioni, Dino De Laurentiis, Ennio Morricone, and Piero Tosi also received the Academy Honorary Award.

Festivals and film awards

[edit]The Association of Italian Film Festivals (AFIC; Italian: Associazione Festival italiani di cinema) is the peak body for film festivals held in Italy.[175][176]

Directors

[edit]Actors and actresses

[edit]See also

[edit]- Media of Italy

- Cinema of the world

- History of cinema

- 100 Italian films to be saved

- List of actors from Italy

- List of actresses from Italy

- List of film directors from Italy

- List of Italian movies

- List of highest-grossing films in Italy

Notes

[edit]- ^ From top left to bottom right: Vittorio De Sica, Sophia Loren, Marcello Mastroianni, Pier Paolo Pasolini, Roberto Rossellini, Sergio Leone, Nino Manfredi, Luchino Visconti, Alberto Sordi, Totò, Gina Lollobrigida, Claudia Cardinale, Anna Magnani, Roberto Benigni, Michelangelo Antonioni, Giancarlo Giannini, Ugo Tognazzi, Bud Spencer, Isabella Rossellini, Federico Fellini, Mario Monicelli, Virna Lisi, Ettore Scola, Alvaro Vitali, and Monica Bellucci

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Table 8: Cinema Infrastructure – Capacity". UNESCO Institute for Statistics. Archived from the original on 5 November 2013. Retrieved 5 November 2013.

- ^ "Table 6: Share of Top 3 distributors (Excel)". UNESCO Institute for Statistics. Archived from the original on 24 December 2018. Retrieved 5 November 2013.

- ^ a b c "Tutti i numeri del cinema italiano 2018" (PDF). ANICA.

- ^ "Country Profiles". Europa Cinemas. Archived from the original on 9 November 2013. Retrieved 9 November 2013.

- ^ Bondanella, Peter (2009). A History of Italian Cinema. A&C Black. ISBN 9781441160690.

- ^ Luzzi, Joseph (30 March 2016). A Cinema of Poetry: Aesthetics of the Italian Art Film. JHU Press. ISBN 9781421419848.

- ^ a b c "L'œuvre cinématographique des frères Lumière – Pays: Italie" (in French). Archived from the original on 20 March 2018. Retrieved 1 January 2022.

- ^ a b c "Il Cinema Ritrovato – Italia 1896 – Grand Tour Italiano" (in Italian). Archived from the original on 21 March 2018. Retrieved 1 January 2022.

- ^ Moliterno, Gino (2009). The A to Z of Italian Cinema (in Italian). Scarecrow Press. p. 243. ISBN 978-0-8108-7059-8.

- ^ a b "Il cinema delle avanguardie" (in Italian). 30 September 2017. Retrieved 13 November 2022.

- ^ Bruni, David (2013). Roberto Rossellini: Roma città aperta (in Italian). Lindau. ISBN 978-88-6708-221-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Katz, Ephraim (2001), "Italy", The Film Encyclopedia, HarperResource, pp. 682–685, ISBN 978-0060742140

- ^ Silvia Bizio; Claudia Laffranchi (2002). Gli italiani di Hollywood: il cinema italiano agli Academy Awards (in Italian). Gremese Editore. ISBN 978-88-8440-177-9.

- ^ Chiello, Alessandro (2014). C'eravamo tanto amati. I capolavori e i protagonisti del cinema italiano (in Italian). Alessandro Chiello. ISBN 978-605-03-2773-1.

- ^ "La Biennale di Venezia – The origin". 7 April 2017. Retrieved 9 September 2018.

- ^ a b "26 febbraio 1896 – Papa Leone XIII filmato Fratelli Lumière" (in Italian). Retrieved 1 January 2022.

- ^ "31 dicembre 1847: nasce a Torino Vittorio Calcina" (in Italian). Retrieved 2 January 2022.

- ^ "Cineteca: pericolosa polveriera per 50 anni di cinema italiano" (in Italian). Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- ^ "Fernaldo Di Giammatteo (1999), "Un raggio di sole si accende lo schermo", in I Cineoperatori. La storia della cinematografia italiana dal 1895 al 1940 raccontata dagli autori della fotografia (volume 1°)" (PDF) (in Italian). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 September 2013. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

- ^ Angelini, Valerio; Fiorangelo Pucci (1981). 1896–1914 Materiali per una storia del cinema delle origini (in Italian). Studio Forma.

... allo stato attuale delle ricerche, la prima proiezione nelle Marche viene ospitata al Caffè Centrale di Ancona: ottobre 1896

[... The present state of research, the first screening will be hosted in the Marches of Ancona at the Café Central: October 1896][ISBN unspecified] - ^ a b c "Storia del cinema italiano" (in Italian). Retrieved 9 January 2022.

- ^ "Italo Pacchioni alle Giornate del Cinema Muto 2009" (in Italian). 25 September 2009. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- ^ "CRITICA CINEMATOGRAFICA" (in Italian). Retrieved 5 January 2022.

- ^ Brunetta, Gian Piero (2003). Guida alla storia del cinema italiano. 1905–2003 (in Italian). Einaudi. p. 425. ISBN 978-8806164850.

- ^ Bruscolini, Elisabetta (2003). Roma nel cinema tra realtà e finzione (in Italian). Fondazione Scuola Nazionale di Cinema. p. 18. ISBN 978-8831776820.

- ^ "Riprese degli operatori Lumière a Torino – Enciclopedia del cinema in Piemonte" (in Italian). Retrieved 5 January 2022.

- ^ Baretta, Marcello (22 July 2016). High Concept Movie (in Italian). Media&Books. ISBN 9788889991190. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

- ^ Della Torre, Roberto (2014). Invito al cinema. Le origini del manifesto cinematografico italiano (in Italian). Educatt. p. 78. ISBN 978-8867800605.

- ^ "Titanus, lo scudo nobile del cinema italiano". La Repubblica. 16 February 2014. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ "La storia di Titanus". Titanus (in Italian). Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ a b "Cinematografia", Dizionario enciclopedico italiano (in Italian), vol. III, Treccani, 1970, p. 226

- ^ Brunetta, Gian Piero (2002). Storia del cinema mondiale (in Italian). Vol. III. Einaudi. p. 38. ISBN 978-88-06-14528-6.

- ^ Verdone, Mario (1970). Spettacolo romano (in Italian). Golem. pp. 141–147.[ISBN unspecified]

- ^ Hall, Sheldon; Neale, Steve (2010). Epics, Spectacles and Blockbusters: A Hollywood History. Wayne State University Press. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-8143-3008-1.

- ^ Fioravanti, Andrea (2006). La "storia" senza storia. Racconti del passato tra letteratura, cinema e televisione (in Italian). Morlacchi Editore. p. 121. ISBN 978-88-6074-066-3.

- ^ "La bellezza del cinema" (in Italian). Retrieved 9 January 2022.

- ^ Brunetta, Gian Piero (2002). Storia del cinema mondiale (in Italian). Vol. III. Einaudi. p. 51. ISBN 978-88-06-14528-6.

- ^ Vv.Aa. (1985). I comici del muto italiano (in Italian). Griffithiana. pp. 24–25.[ISBN unspecified]

- ^ Brunetta, Gian Piero (2009). Cinema muto italiano (in Italian). Laterza. p. 46. ISBN 978-8858113837.

- ^ "Cinema of Italy: Avant-garde (1911-1919)". Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- ^ Heil, Jerry (1986). "Russian Futurism and the Cinema: Majakovskij's Film Work of 1913". Russian Literature. 19 (2): 175–191. doi:10.1016/S0304-3479(86)80003-5.

- ^ "What Causes German Expressionism?". Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- ^ "Il Futurismo: un trionfo italiano a New York" (in Italian). Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- ^ The 20th-Century art book (Reprinted. ed.). dsdLondon: Phaidon Press. 2001. ISBN 978-0714835426.

- ^ Vivarelli, Nick (17 February 2024). "Italian Film Business Bounces Back With Production Percolating as Box Office Picks Up". Variety. Retrieved 8 June 2024.

- ^ Ricci, Steve (2008). Cinema and Fascism: Italian Film and Society, 1922–1943. University of California Press. p. 4. ISBN 9780520941281.

- ^ Brunetta, Gian Piero (2002). Storia del cinema mondiale (in Italian). Vol. I. Einaudi. p. 245. ISBN 978-88-06-14528-6.

- ^ Brunetta, Gian Piero (2002). Storia del cinema mondiale (in Italian). Vol. III. Einaudi. p. 57. ISBN 978-88-06-14528-6.

- ^ Brunetta, Gian Piero (2009). Cinema muto italiano (in Italian). Laterza. p. 56. ISBN 978-8858113837.

- ^ Foster, Gwendolyn Audrey (1995). Women Film Directors: An International Bio-Critical Dictionary. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 282–284. ISBN 978-0313289729.

- ^ Callisto Cosulich, Primo contatto con la realtà in Eco del cinema e dello spettacolo, n.77 on 31 July 1954.

- ^ Brunetta, Gian Piero (2009). Cinema muto italiano (in Italian). Laterza. pp. 59–60. ISBN 978-8858113837.

- ^ Gori, Gianfranco (1984). Alessandro Blasetti (in Italian). La Nuova Italia. p. 20.[ISBN unspecified]

- ^ "'Frank Capra: Mr. America' Review: Documentary Gives Penetrating Insight Into Filmmaker Who Made Classics But Also Named Names – Venice Film Festival". Deadline. 1 September 2023. Retrieved 8 June 2024.

- ^ Anderson, Ariston (24 July 2014). "Venice: David Gordon Green's 'Manglehorn,' Abel Ferrara's 'Pasolini' in Competition Lineup". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on 18 February 2016.

- ^ Valck, Marijke de; Kredell, Brendan; Loist, Skadi (26 February 2016). Film Festivals: History, Theory, Method, Practice. Routledge. ISBN 9781317267218.

- ^ "Addio, Lido: Last Postcards from the Venice Film Festival". Time. Retrieved 9 September 2018.

- ^ "50 unmissable film festivals". Variety. 8 September 2007. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- ^ a b "Cinecittà, c'è l'accordo per espandere gli Studios italiani" (in Italian). 30 December 2021. Retrieved 10 September 2022.

- ^ Kinder, Lucy (28 April 2014). "Cinecittà studios: Google Doodle celebrates 77th anniversary".

- ^ Ricci, Steven (1 February 2008). Cinema and Fascism: Italian Film and Society, 1922–1943. University of California Press. pp. 68–69–. ISBN 978-0-520-94128-1.

- ^ Garofalo, Piero (2002). "Seeing Red: The Soviet Influence on Italian Cinema in the Thirties". In Reich, Jacqueline; Garofalo, Piero (eds.). Re-viewing Fascism: Italian Cinema, 1922-1943. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 223–249. ISBN 978-0253215185.

- ^ Bondanella, Peter E. (2001). Italian Cinema: From Neorealism to the Present. Continuum. p. 13. ISBN 9780826412478.

- ^ Bondanella, Peter (1995). Italian Cinema From Neorealism to the Present. The Continuum Publishing Company. p. 19. ISBN 978-0826404268.

- ^ "The Cinema Under Mussolini". Ccat.sas.upenn.edu. Archived from the original on 31 July 2010. Retrieved 30 October 2010.

- ^ Brunetta, Gian Piero (2002). Storia del cinema mondiale (in Italian). Vol. III. Einaudi. p. 356. ISBN 978-88-06-14528-6.

- ^ Brunetta, Gian Piero (1991). Cent'anni di cinema italiano (in Italian). Laterza. pp. 251–257. ISBN 978-8842046899.

- ^ "MERLINI, Elsa" (in Italian). Retrieved 16 November 2022.

- ^ a b Brunetta, Gian Piero (2002). Storia del cinema mondiale (in Italian). Vol. III. Einaudi. pp. 352–355. ISBN 978-88-06-14528-6.

- ^ Brunetta, Gian Piero; Gili, Jean (2000). L'ora d'Africa del cinema italiano, 1911-1989 (in Italian). Materiali di Lavoro.[ISBN unspecified]

- ^ Brunetta, Gian Piero (2002). Storia del cinema mondiale (in Italian). Vol. III. Einaudi. p. 354. ISBN 978-88-06-14528-6.

- ^ a b Brunetta, Gian Piero (2002). Storia del cinema mondiale (in Italian). Vol. III. Einaudi. p. 355. ISBN 978-88-06-14528-6.

- ^ Brunetta, Gian Piero (2002). Storia del cinema mondiale (in Italian). Vol. III. Einaudi. pp. 357–359. ISBN 978-88-06-14528-6.

- ^ Brunetta, Gian Piero (2002). Storia del cinema mondiale (in Italian). Vol. IV. Einaudi. pp. 670 and following. ISBN 978-88-06-14528-6.

- ^ a b Iannini, Tommaso (2010). Tutto Cinema (in Italian). De Agostini. p. 235. ISBN 978-8841858257.

- ^ "Vittorio De Sica: l'eclettico regista capace di fotografare la vera Italia" (in Italian). 6 July 2020. Retrieved 14 January 2022.

- ^ a b c Bergan, Ronald (2011). The Film Book. Penguin. p. 154. ISBN 9780756691882.

- ^ a b "Umberto D (regia di Vittorio De Sica, 1952, 89', drammatico)" (in Italian). Retrieved 9 January 2022.

- ^ Ebert, Roger. "The Bicycle Thief / Bicycle Thieves (1949)". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on 27 February 2009. Retrieved 8 September 2011.

- ^ "IL CINEMA IN ITALIA NEGLI ANNI '50" (in Italian). Retrieved 9 January 2022.

- ^ a b Tassone, Aldo (2002). I film di Michelangelo Antonioni: un poeta della visione (in Italian). Gremese editore.[ISBN unspecified]

- ^ ""Capriccio all'italiana", l'ultimo film interpretato da Totò" (in Italian). 5 May 2021. Retrieved 20 December 2022.

- ^ "Il 15 febbraio 1898 nasceva Totò, simbolo della comicità napoletana" (in Italian). Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ Giacovelli, Enrico (1990). La commedia all'italiana - La storia, i luoghi, gli autori, gli attori, i film (in Italian). Gremese Editore. pp. 23–24. ISBN 978-8876058738.

- ^ "Europe Choosey on Films, Sez Reiner; Sluffs Flops". Variety. 9 September 1953. p. 7. Retrieved 29 September 2019 – via Archive.org.

- ^ "1953 at the box office". Box Office Story.

- ^ Wrigley, Richard (2008). Cinematic Rome. Troubador Publishing. p. 52. ISBN 978-1906510282.

- ^ Lucanio, Patrick (1994). With Fire and Sword: Italian Spectacles on American Screens, 1958–1968. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0810828162.

- ^ "Il miglior film di tutti i tempi: "Il Padrino" o "8 e mezzo"?" (in Italian). Retrieved 14 January 2022.

- ^ Ennio Flaiano, the film's co-screenwriter and creator of Paparazzo, explained that he took the name from Signor Paparazzo, a character in George Gissing's novel By the Ionian Sea (1901). See Bondanella, Peter (1994). The Cinema of Federico Fellini. Guaraldi. p. 136. ISBN 978-0691008752.

- ^ "Franco e Ciccio in mostra" (in Italian). 10 December 2013. Retrieved 3 December 2022.

- ^ Hotz, Stephanie Aneel (2017). The Italian musicarello : youth, gender, and modernization in postwar popular cinema – Texas Scholar Works (Thesis). doi:10.26153/tsw/2764. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- ^ Lino Aulenti (2011). Storia del cinema italiano. libreriauniversitaria, 2011. ISBN 978-8862921084.

- ^ a b "Musicarello" (in Italian). Retrieved 30 November 2022.

- ^ "Canzoni, canzoni, canzoni" (in Italian). Retrieved 30 November 2022.

- ^ "I musicarelli" (in Italian). Retrieved 30 November 2022.

- ^ Pavone, Giuliano (1999). Giovannona Coscialunga a Cannes: Storia e riabilitazione della commedia all'italiana anni '70 (in Italian). Tarab. ISBN 978-8886675499.

- ^ "La Commedia Italiana:Classifica dei 10 Musicarelli più importanti degli anni '50 e '60" (in Italian). Retrieved 30 November 2022.

- ^ a b Della Casa, Steve; Manera, Paolo (1991). "I musicarelli". Cineforum. p. 310.

- ^ "Divorzio all'italiana (1961) di Pietro Germi" (in Italian). Retrieved 21 November 2022.

- ^ "Commedia all'italiana" (in Italian). Treccani. Retrieved 21 November 2022.

- ^ Brunetta, Gian Piero (1993). "Dal miracolo economico agli anni novanta, 1960-1993". Storia del cinema italiano (in Italian). Vol. IV. Editori Riuniti. pp. 139–141. ISBN 88-359-3788-4.

- ^ "The 50 Greatest Directors and Their 100 Best Movies". Entertainment Weekly. 19 April 1996. Archived from the original on 7 June 2019. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- ^ "Greatest Film Directors". Filmsite.org. Archived from the original on 5 September 2019. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- ^ Gelten, Simon; Lindberg (10 November 2015). "Introduction". Spaghetti Western Database. Archived from the original on 30 June 2017. Retrieved 2 May 2021.

- ^ "Sergio Leone creatore degli 'spaghetti-western'" (in Italian). Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 29 November 2022.

- ^ "I film di Sergio Leone, re dello spaghetti western" (in Italian). 30 April 2013. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 29 November 2022.

- ^ Pezzotta, Alberto (1995). Mario Bava. Milan: Il Castoro Cinema.

- ^ "Mario Bava: Maestro of the Macabre (2000)–MUBI". Retrieved 2 December 2022.

- ^ "Archivio Corriere della Sera". archivio.corriere.it.

- ^ "Dario Argento - Master of Horror". MYmovies.it.

- ^ Simpson, Clare (4 February 2013). "Watch Me While I Kill: Top 20 Italian Giallo Films". WhatCulture. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015.

- ^ Kerswell, J.A. (2012). The Slasher Movie Book. Chicago Review Press. pp. 46–49. ISBN 978-1556520105.

- ^ "10 Giallo Films for Beginners". Film School Rejects. 13 October 2018. Retrieved 27 December 2020.

- ^ Koven, Mikel (2 October 2006). La Dolce Morte: Vernacular Cinema and the Italian Giallo Film. Scarecrow Press. p. 66. ISBN 0810858703.

- ^ "La ragazza che sapeva troppo" (in Italian). 3 February 2012. Retrieved 2 December 2022.

- ^ Anne Billson (14 October 2013). "Violence, mystery and magic: how to spot a giallo movie". The Tekegraph. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 29 August 2014.

- ^ a b Abrams, Jon (16 March 2015). "GIALLO WEEK! YOUR INTRODUCTION TO GIALLO FEVER!". The Daily Grindhouse. Archived from the original on 24 March 2015. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- ^ For a continuation of this kind in the 2000s, see "Cinema & cinema: "La tenerezza" di Gianni Amelio", according to which "The tenderness" of Amelio "refers to the whole of Italy affected by corruption inveterate by frustrations without escape from racist hatred: it refers to that sense of death, of paralysis, of the lack of ideal perspectives, which Italian films have incessantly recorded for years ".

- ^ "Il Cinema Politico - Il Davinotti" (in Italian). Retrieved 10 November 2015.

- ^ "Lina Wertmuller: "Agli Oscar credo poco, preferisco pensare al nuovo film"" (in Italian). 21 September 2015. Retrieved 5 January 2022.

- ^ Mereghetti, Paolo (2011). Dizionario dei film 2011 (in Italian). B.G Dalai editore. p. 1423. ISBN 978-88-6073-626-0.

- ^ Mereghetti, Paolo (2011). Dizionario dei film 2011 (in Italian). B.G Dalai editore. p. 1654. ISBN 978-88-6073-626-0.

- ^ "Violent Italy: A Poliziotteschi Primer". 13 September 2015. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- ^ Curti, Roberto (2013). Italian Crime Filmography, 1968–1980. McFarland. ISBN 9781476612089.

- ^ "Spaghetti western star Bud Spencer dies". BBC News. 28 June 2016.

He frequently appeared as part of a double act alongside Terence Hill

- ^ Peter E. Bondanella (12 October 2009). A history of Italian cinema. Continuum International Publishing Group, 2009. ISBN 978-1441160690.

- ^ "Fantozzi" (in Italian). Retrieved 4 December 2022.

- ^ "Fantozziano" (in Italian). Retrieved 4 December 2022.

- ^ "Fantozzi, antieroe moderno" (in Italian). 13 March 2019. Retrieved 3 December 2022.

- ^ "Aldo Grasso: "Villaggio l'ha sfruttato troppo Molto meglio il suo Fracchia televisivo"" (in Italian). 17 October 2015. Retrieved 3 December 2022.

- ^ "CantaNapoli: La sceneggiata di Mario Merola". July 2020. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- ^ "Nino D'Angelo: uno show per i suoi 60 anni. L'intervista". 13 June 2017. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- ^ Roberto Poppi (2002). I registi: dal 1930 ai giorni nostri. Gremese Editore, 2002. p. 180. ISBN 8884401712.

- ^ Roberto Curti (22 October 2013). Italian Crime Filmography, 1968-1980. McFarland, 2013. ISBN 978-0786469765.

- ^ "Ennio Morricone compie novant'anni, cinque cose che non sapete sul genio italiano della colonna sonora" (in Italian). Retrieved 14 January 2022.

- ^ Zagarrio, Vito (2005). Storia del cinema italiano 1977/1985 (in Italian). Marsilio. p. 329. ISBN 978-8831785372.

- ^ Zagarrio, Vito (2005). Storia del cinema italiano 1977/1985 (in Italian). Marsilio. p. 348. ISBN 978-8831785372.

- ^ "Italia 80" (in Italian). 4 October 2012. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

- ^ Rooney, David (7 January 2002). "Local yokels deliver a boffo B.O holiday gift". Variety. p. 30.

- ^ "Le migliori 50 commedie italiane degli anni 80" (in Italian). 21 March 2021. Retrieved 25 November 2022.

- ^ Vitti, Antonio (2012). "Introduzione. Cinema italiano contemporaneo". Annali d'Italianistica (in Italian). 30: 17–29. JSTOR 24017598. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

- ^ D'Agostini, Paolo (29 January 1999). "Il cinema italiano da Moretti a oggi". Storia del cinema mondiale (in Italian). Einaudi. pp. 1102–1103. ISBN 978-8806145286.

- ^ "Pieraccioni, Leonardo". Treccani Encyclopedia. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- ^ "E Il Ciclone, film record, va in tv". la Repubblica. 23 October 1999. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- ^ "Vent'anni dopo Il Ciclone è un cult. Pieraccioni lo celebra tra Conti e Panariello". la Repubblica. 3 September 2016. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- ^ "Movieplayer.it - Pagina incassi del film" (in Italian). Retrieved 19 January 2008.

- ^ "FILM ITALIANI 1995" (in Italian). Retrieved 22 January 2022.

- ^ "FILM ITALIANI 2005" (in Italian). Retrieved 22 January 2022.

- ^ "RAPPORTO – Il Mercato e l'Industria del Cinema in Italia – 2008" (PDF) (in Italian). Retrieved 22 January 2022.

- ^ "L'Apetta Giulia e la Signora Vita" (in Italian). 22 November 2006. Archived from the original on 25 May 2011. Retrieved 6 September 2008.

- ^ a b "'Perfetti Sconosciuti' da Guinness, la commedia di Genovese è il film con più remake di sempre". Repubblica Tv – la Repubblica.it (in Italian). 15 July 2019. Retrieved 16 July 2019.

- ^ Anderson, Ariston (4 January 2016). "Italy Box Office: Local Hit 'Quo Vado?' Sets Opening Records". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- ^ Lyman, Eric J. (4 November 2013). "Italian Comedy 'Sun in Buckets' Sets New Opening Weekend Sales Record". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- ^ Barcaro, Gabriele (25 August 2008). "Fabio Ferzetti, Venice Days General Delegate". Cineuropa. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- ^ Massimo Borriello (4 March 2008). "Cento film e un'Italia da non dimenticare". Movieplayer. Retrieved 19 April 2013.

- ^ "Ecco i cento film italiani da salvare". Corriere della Sera. 28 February 2008. Retrieved 19 April 2013.

- ^ "CINETECA NAZIONALE DI ROMA" (in Italian). Retrieved 9 January 2022.

- ^ "Cineteca" (in Italian). Retrieved 6 January 2022.

- ^ "Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia" (in Italian). Retrieved 6 January 2022.

- ^ "Cineteca Nazionale". Archived from the original on 19 March 2014. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Fondazione Cineteca Italiana (FCI) — filmarchives online" (in Italian). Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- ^ "1962, nasce la Cineteca di Bologna: 53 anni di storia in un video" (in Italian). Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- ^ "Touring Club Italiano – Dossier Musei 2009" (PDF) (in Italian). Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 April 2012. Retrieved 16 January 2022.