Ethel Reed

Ethel Reed | |

|---|---|

A photograph of Ethel Reed by Frances Benjamin Johnston (ca. 1895) | |

| Born | March 13, 1874 |

| Died | March 1, 1912 (aged 37) London, United Kingdom |

| Style | Graphic arts |

Ethel Reed (March 13, 1874 – March 1, 1912) was an American graphic artist.[1][2] In the 1890s, her works received critical acclaim in America and Europe. In 2016, they were on exhibit in the Metropolitan Museum of Art and Museum of Modern Art in New York, the National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C., the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, the Frederick R. Weisman Art Museum of the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, and the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City.

Early life and career

[edit]Reed was born in Newburyport, Massachusetts on March 13, 1874. She was the daughter of a local photographer Edgar Eugene Reed and Mary Elizabeth Mahoney, an immigrant from County Cork, Ireland. Her father died of tuberculosis in 1892,[3] and Reed and her mother consequently suffered hardship. After they moved to Boston in 1890, she studied briefly at the Cowles Art School in 1893, and after 1894 began to receive public notice for her illustrations. Reed's youthful beauty and cleverness caught the attention of a Newburyport artist Laura Hills, who became a mentor.[4] During her time in Boston, she achieved national fame as a poster artist while still in her early 20s. She did many series of posters and book illustrations during a span of less than two years.[5] In the mid-1890s she was engaged to fellow artist Philip Leslie Hale, whose father Edward Everett Hale was a prominent Bostonian. However, the engagement was broken off. In 1896, she traveled Europe with her mother. In 1897, they settled in London where Reed worked as an illustrator, in particular for The Yellow Book, a quarterly literary periodical which was co-founded by Aubrey Beardsley. She had two children with different lovers.[6]

Reed was acquainted with important literary and artistic figures of her day, including the writer Richard le Gallienne, the architects Bertram Goodhue and Ralph Adams Cram, and the photographer Fred Holland Day. She was the model for Day's photographs Chloe and The Gainsborough Hat. She also modeled at least three times for portraits by Frances Benjamin Johnston.[7]

In her short career, Reed achieved recognition as one of the preeminent illustrator artists of her time and remains one of the most mysterious figures of American graphic design.[5][8][9][10][11][12][13][14]

Later life and death

[edit]Reed was unable to find work after moving to Europe; she turned to drugs and alcohol after years of disappointment.[6] Her circumstances in England are difficult to trace, and certain records of her final years have yet to surface.[15] However, according to research, she died in her sleep in 1912.[2] Her biographer has asserted that alcoholism and the use of sleeping medications contributed to her death.[16]

Works illustrated

[edit]- Boston Sunday Herald (1895)[17]

- Boston Illustrated (1895)[18]

- Lily Lewis Rood, Pierre Puvis de Chavannes: A Sketch (Boston: L. Prang & Co., 1895)[19]

- Albert Morris Bagby, Miss Träumerei: A Weimar Idyl (Boston: Lamson, Wolffe & Co., 1895)[20]

- Gertrude Smith, The Arabella and Araminta Stories (Boston: Copeland & Day, 1895)[21]

- Julia Ward Howe, Is Polite Society Polite? (Boston: Lamson, Wolffe & Co., 1895)[22]

- Charles Knowles Bolton, The Love Story of Ursula Wolcott (Boston: Lamson, Wolffe, & Co., 1896)

- Mabel Fuller Blodgett, Fairy Tales (Boston: Lamson, Wolffe, & Co., 1896)

- Louise Chandler Moulton, In Childhood's Country (Boston: Copeland & Day, 1896)[23]

- Time and the Hour, (1896)[24]

- Richard Le Gallienne, The Quest of the Golden Girl: A Romance (London: John Lane, 1897)[25]

- The Yellow Book, Volumes XII (January 1897) and XIII (April 1897)

- Agnes Lee, The Round Rabbit and Other Child Verse (Boston: Copeland & Day, 1898).

- The Sketch, Volume 21 (April 6, 1898)

-

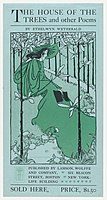

Book cover by Ethel Reed

-

Book cover for The House of the Trees and Other Poems

-

Poster for The Quest of the Golden Girl, published in Les Maîtres de l'Affiche

References

[edit]- ^ "Ethel Reed, The Beautiful Poster Lady Who Disappeared". New England Historical Society. 2018. Archived from the original on October 2, 2022. Retrieved February 10, 2023.

- ^ a b Peterson, William S. (2013a). The Beautiful Poster Lady: A Life of Ethel Reed. Oak Knoll Press. ISBN 978-1-58456-317-4.

- ^ Peterson 2013a, pp. 2–5.

- ^ Barrie, J. M. (1895). "A Chat with Miss Ethel Reed". The Bookman. 2 (4): 277–281 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ a b Wright, Helena E. (March 23, 2015). "Ethel Reed and the poster craze". National Museum of American History. Archived from the original on November 20, 2022. Retrieved August 31, 2022.

- ^ a b Townsend, Sloane (April 8, 2019). "Ethel Reed". History of Graphical Design. NC State University. Archived from the original on October 10, 2019. Retrieved December 23, 2019.

- ^ Ranson, Sadi (2001). "Redefining Fine Art: Sarah Sears, Laura Hills, and Ethel Reed". A Studio of Her Own: Women Artists in Boston, 1870-1940. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts. pp. 55–74. ISBN 978-0-87846-482-1 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Ethel Reed". World of Art Global Limited. Archived from the original on January 16, 2021.

- ^ Hills, Patricia (1977). Turn-of-the-Century America: Paintings, Graphics, Photographs, 1890-1910. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art. pp. 59–60, 63 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Keay, Carolyn (1975). American Posters of the Turn of the Century. New York: St. Martin's Press. pp. 17–18, 30–31, 93. ISBN 978-0-85670-207-5 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Kiehl, David W. (1987). "American Art Posters of the 1890s". American Art Posters of the 1890s in The Metropolitan Museum of Art, including the Leonard A. Lauder Collection. Catalogue by David W. Kiehl. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. pp. 15–20, 40–41. ISBN 0-87099-501-4 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Finlay, Nancy (1987). "American Posters and Publishing in the 1890s". American Art Posters of the 1890s in The Metropolitan Museum of Art, including the Leonard A. Lauder Collection. Catalogue by David W. Kiehl. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. pp. 50–51, 55. ISBN 0-87099-501-4 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Cate, Philip Dennis (1987). "The French Posters 1868-1900". American Art Posters of the 1890s in The Metropolitan Museum of Art, including the Leonard A. Lauder Collection. Catalogue by David W. Kiehl. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. pp. 86, 88, 118. ISBN 0-87099-501-4 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Kiehl, David W. (1987). "A Catalogue of American Art Posters of the 1890s". American Art Posters of the 1890s in The Metropolitan Museum of Art, including the Leonard A. Lauder Collection. Catalogue by David W. Kiehl. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. pp. 164–168. ISBN 0-87099-501-4 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ McAllister, Jim (March 1, 2010). "Essex County Chronicles: Local artist's life still shrouded in mystery". The Salem News. Archived from the original on November 9, 2013. Retrieved February 11, 2023.

- ^ Peterson, William (May 30, 2013b). "Vanished in the Fog: Ethel Reed, the Beautiful Poster Lady". Library of Congress. Archived from the original on February 11, 2023. Retrieved February 11, 2023.

- ^ "The Boston Herald: Fashion Supplement, March 24 [1895]". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Archived from the original on February 12, 2023. Retrieved February 11, 2023.

- ^ "The Best Guide to Boston [1895]". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Archived from the original on December 23, 2019. Retrieved December 23, 2019.

- ^ "Pierre Puvis de Chavannes: A Sketch [1895]". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Archived from the original on February 12, 2023. Retrieved February 11, 2023.

- ^ "Miss Träumerei [1895]". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Archived from the original on February 12, 2023. Retrieved December 23, 2019.

- ^ "Arabella and Araminta Stories [1895]". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Archived from the original on February 12, 2023. Retrieved February 11, 2023.

- ^ "Is Polite Society Polite? [1895]". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Archived from the original on February 12, 2023. Retrieved December 23, 2019.

- ^ "In Childhood's Country [1896]". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Archived from the original on February 14, 2022. Retrieved December 23, 2019.

- ^ "Time and the Hour [1896]". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Archived from the original on February 12, 2023. Retrieved December 23, 2019.

- ^ "The Quest of the Golden Girl [1897]". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Archived from the original on February 12, 2023. Retrieved December 23, 2019.

External links

[edit]- Ethel Reed in Prints & Photographs Online Catalog of the Library of Congress

- Ethel Reed in New York Public Library Digital Collection

- Ethel Reed in Ask Art

- Featured Book Artist: The Evanescent Miss Ethel Reed on University Press Books (archived from the original[dead link])

- Ethel Reed Information about her life and artistic career on WordPress

- The Beautiful Poster Lady An Interview with William S. Peterson, Professor Emeritus of English at the University of Maryland – Fine Books Magazine

- Ethel Reed, The Beautiful Poster Lady. Webcast from the Rare Book and Special Collections Division at the Library of Congress

- 1874 births

- 1912 deaths

- 19th-century American artists

- 19th-century American women artists

- 20th-century American artists

- 20th-century American women artists

- American graphic designers

- American illustrators

- American women graphic designers

- American women illustrators

- Artists from Massachusetts

- Book designers

- People from Newburyport, Massachusetts