нацизм

| Часть серии о |

| нацизм |

|---|

| Часть серии о |

| Фашизм |

|---|

|

| Часть серии о |

| Антисемитизм |

|---|

|

|

|

Нацизм ( / ˈ n ɑː t s ɪ z əm , ˈ n æ t -/ NA(H)T -siz-əm ), формально национал-социализм ( NS ; немецкий : Nationalsozialismus , Немецкий: [natsi̯oˈnaːlzotsi̯aˌlɪsmʊs] ), — это крайне правая тоталитарная социально-политическая идеология и практика, связанная с Адольфом Гитлером и нацистской партией (НСДАП) в Германии. [ 1 ] [ 2 ] [ 3 ] Во время прихода Гитлера к власти в Европе в 1930-х годах его часто называли гитлеровским фашизмом ( нем . Гитлерфашизм ) и гитлеризмом ( нем . Гитлеризм ). Поздний термин « неонацизм » применяется к другим крайне правым группам с аналогичными идеями, которые сформировались после Второй мировой войны , когда распался Третий Рейх .

Нацизм – это форма фашизма . [ 4 ] [ 5 ] [ 6 ] [ 7 ] с презрением к либеральной демократии и парламентской системе . Оно включает в себя диктатуру , [ 3 ] ярый антисемитизм , антикоммунизм , антиславянство , [ 8 ] антицыганские настроения , научный расизм , превосходство белой расы , нордизм , социальный дарвинизм и использование евгеники в своем вероучении. Его крайний национализм зародился в пангерманизме и этнонационалистическом движении Völkisch , которое было заметным аспектом немецкого ультранационализма с конца 19 века. На нацизм оказали сильное влияние формирования Freikorps военизированные , возникшие после поражения Германии в Первой мировой войне , из которых возник основной «культ насилия» партии. [ 9 ] Оно придерживалось псевдонаучных теорий расовой иерархии , [ 10 ] идентифицируя этнических немцев как часть того, что нацисты считали арийской или нордической господствующей расой . [ 11 ] Нацизм стремился преодолеть социальные разногласия и создать однородное немецкое общество, основанное на расовой чистоте , которое представляло бы народную общность ( Volksgemeinschaft ). Нацисты стремились объединить всех немцев, живущих на исторически немецкой территории, а также получить дополнительные земли для немецкой экспансии в рамках доктрины Lebensraum и исключить тех, кого они считали либо чуждыми сообществам , либо «низшими» расами ( Untermenschen ).

Термин «национал-социализм» возник в результате попыток создать националистическое переопределение социализма как альтернативу марксистскому международному социализму и капитализму свободного рынка . Нацизм отвергал марксистские концепции классового конфликта и всеобщего равенства , выступал против космополитического интернационализма и стремился убедить все части нового немецкого общества подчинить свои личные интересы « общему благу », приняв политические интересы в качестве главного приоритета экономической организации. [ 12 ] которые, как правило, соответствовали общим взглядам на коллективизм или коммунитаризм, а не на экономический социализм. Предшественница нацистской партии, пангерманская националистическая и антисемитская Немецкая рабочая партия (ДАП), была основана 5 января 1919 года. К началу 1920-х годов партия была переименована в Национал-социалистическую немецкую рабочую партию, чтобы апеллировать к левым. рабочие крыла, [ 13 ] переименование, против которого первоначально возражал Гитлер. [ 14 ] Национал -социалистическая программа , или «25 пунктов», была принята в 1920 году и призывала к созданию объединенной Великой Германии , которая отказывала бы в гражданстве евреям или лицам еврейского происхождения, а также поддерживала земельную реформу и национализацию некоторых отраслей промышленности. В книге «Майн кампф» («Моя борьба»), опубликованной в 1925–1926 годах, Гитлер изложил антисемитизм и антикоммунизм, лежащие в основе его политической философии, а также свое презрение к представительной демократии , в отношении которой он предложил принцип фюрера ( принцип лидера ). и его вера в право Германии на территориальную экспансию посредством жизненного пространства . [ 15 ] Цели Гитлера включали расширение немецких территорий на восток , немецкую колонизацию Восточной Европы и продвижение союза с Великобританией и Италией против Советского Союза .

Нацистская партия получила наибольшую долю голосов избирателей на двух всеобщих выборах в Рейхстаг в 1932 году, что сделало ее самой крупной партией в законодательном органе на сегодняшний день, хотя ей все еще не хватает абсолютного большинства ( 37,3% 31 июля 1932 года и 33,1% 6 июля 1932 года). ноябрь 1932 г. ). Поскольку ни одна из партий не желала или не могла сформировать коалиционное правительство, Гитлер был назначен канцлером Германии 30 января 1933 года президентом Паулем фон Гинденбургом при поддержке и попустительстве традиционных консервативных националистов, которые считали, что могут контролировать его и его партию. . Благодаря использованию Гинденбургом чрезвычайных президентских указов и изменению Веймарской конституции , которое позволило кабинету министров управлять страной посредством прямых указов, минуя Гинденбург и Рейхстаг, нацисты вскоре создали однопартийное государство и начали Gleichschaltung .

The Sturmabteilung (SA) and the Schutzstaffel (SS) functioned as the paramilitary organisations of the Nazi Party. Using the SS for the task, Hitler purged the party's more socially and economically radical factions in the mid-1934 Night of the Long Knives, including the leadership of the SA. After the death of President Hindenburg on 2 August 1934, political power was concentrated in Hitler's hands and he became Germany's head of state as well as the head of the government, with the title of Führer und Reichskanzler, meaning "leader and Chancellor of Germany" (see also here). From that point, Hitler was effectively the dictator of Nazi Germany – also known as the Third Reich – under which Jews, political opponents and other "undesirable" elements were marginalised, imprisoned or murdered. During World War II, many millions of people – including around two-thirds of the Jewish population of Europe – were eventually exterminated in a genocide which became known as the Holocaust. Following Germany's defeat in World War II and the discovery of the full extent of the Holocaust, Nazi ideology became universally disgraced. It is widely regarded as evil, with only a few fringe racist groups, usually referred to as neo-Nazis, describing themselves as followers of National Socialism. The use of Nazi symbols is outlawed in many European countries, including Germany and Austria.

Etymology

The full name of the Nazi Party was Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (German for 'National Socialist German Workers' Party') and they officially used the acronym NSDAP. The term "nazi" had been in use, before the rise of the NSDAP, as a colloquial and derogatory word for a backwards farmer or peasant. It characterised an awkward and clumsy person, a yokel. In this sense, the word Nazi was a hypocorism of the German male name Igna(t)z (itself a variation of the name Ignatius)—Igna(t)z being a common name at the time in Bavaria, the area from which the NSDAP emerged.[16][17]

In the 1920s, political opponents of the NSDAP in the German labour movement seized on this. Using the earlier abbreviated term Sozi for Sozialist (German for 'Socialist') as an example,[18] they shortened the NSDAP's name, Nationalsozialistische, to the dismissive "Nazi", in order to associate them with the derogatory use of the aforementioned term.[19][17][20][21][22][23] The first use of the term "Nazi" by the National Socialists occurred in 1926 in a publication by Joseph Goebbels called Der Nazi-Sozi ["The Nazi-Sozi"]. In Goebbels' pamphlet, the word "Nazi" only appears when linked with the word "Sozi" as an abbreviation of "National Socialism".[24]

After the NSDAP's rise to power in the 1930s, the use of the term "Nazi" by itself or in terms such as "Nazi Germany", "Nazi regime", and so on was popularised by German exiles outside the country, but not in Germany. From them, the term spread into other languages and it was eventually brought back into Germany after World War II.[20] The NSDAP briefly adopted the designation "Nazi" in an attempt to reappropriate the term, but it soon gave up this effort and generally avoided using the term while it was in power.[20][21] In each case, the authors typically referred to themselves as "National Socialists" and their movement as "National Socialism", but never as "Nazis". A compendium of Hitler's conversations from 1941 through 1944 entitled Hitler's Table Talk does not contain the word "Nazi" either.[25] In speeches by Hermann Göring, he never uses the term "Nazi".[26] Hitler Youth leader Melita Maschmann wrote a book about her experience entitled Account Rendered.[27] She did not refer to herself as a "Nazi", even though she was writing well after World War II. In 1933, 581 members of the National Socialist Party answered interview questions put to them by Professor Theodore Abel from Columbia University. They similarly did not refer to themselves as "Nazis".[28]

Position within the political spectrum

The majority of scholars identify Nazism in both theory and practice as a form of far-right politics.[1] Far-right themes in Nazism include the argument that superior people have a right to dominate other people and purge society of supposed inferior elements.[29] Adolf Hitler and other proponents denied that Nazism was either left-wing or right-wing: instead, they officially portrayed Nazism as a syncretic movement.[30][31] In Mein Kampf, Hitler directly attacked both left-wing and right-wing politics in Germany, saying:

Today our left-wing politicians in particular are constantly insisting that their craven-hearted and obsequious foreign policy necessarily results from the disarmament of Germany, whereas the truth is that this is the policy of traitors ... But the politicians of the Right deserve exactly the same reproach. It was through their miserable cowardice that those ruffians of Jews who came into power in 1918 were able to rob the nation of its arms.[32]

In a speech given in Munich on 12 April 1922, Hitler stated:

There are only two possibilities in Germany; do not imagine that the people will forever go with the middle party, the party of compromises; one day it will turn to those who have most consistently foretold the coming ruin and have sought to dissociate themselves from it. And that party is either the Left: and then God help us! for it will lead us to complete destruction—to Bolshevism, or else it is a party of the Right which at the last, when the people is in utter despair, when it has lost all its spirit and has no longer any faith in anything, is determined for its part ruthlessly to seize the reins of power—that is the beginning of resistance of which I spoke a few minutes ago.[33]

Hitler at times redefined socialism. When George Sylvester Viereck interviewed Hitler in October 1923 and asked him why he referred to his party as 'socialists' he replied:

Socialism is the science of dealing with the common weal. Communism is not Socialism. Marxism is not Socialism. The Marxians have stolen the term and confused its meaning. I shall take Socialism away from the Socialists. Socialism is an ancient Aryan, Germanic institution. Our German ancestors held certain lands in common. They cultivated the idea of the common weal. Marxism has no right to disguise itself as socialism. Socialism, unlike Marxism, does not repudiate private property. Unlike Marxism, it involves no negation of personality, and unlike Marxism, it is patriotic.[34]

In 1929, Hitler gave a speech to a group of Nazi leaders and simplified 'socialism' to mean, "Socialism! That is an unfortunate word altogether... What does socialism really mean? If people have something to eat and their pleasures, then they have their socialism."[35] When asked in an interview on 27 January 1934 whether he supported the "bourgeois right-wing", Hitler claimed that Nazism was not exclusively for any class and he indicated that it favoured neither the left nor the right, but preserved "pure" elements from both "camps" by stating: "From the camp of bourgeois tradition, it takes national resolve, and from the materialism of the Marxist dogma, living, creative Socialism."[36]

Historians regard the equation of Nazism as "Hitlerism" as too simplistic since the term was used prior to the rise of Hitler and the Nazis. In addition, the different ideologies incorporated into Nazism were already well established in certain parts of German society long before World War I.[37] The Nazis were strongly influenced by the post–World War I far-right in Germany, which held common beliefs such as anti-Marxism, anti-liberalism and antisemitism, along with nationalism, contempt for the Treaty of Versailles and condemnation of the Weimar Republic for signing the armistice in November 1918 which later led it to sign the Treaty of Versailles.[38] A major inspiration for the Nazis were the far-right nationalist Freikorps, paramilitary organisations that engaged in political violence after World War I.[38] Initially, the post–World War I German far-right was dominated by monarchists, but the younger generation, which was associated with völkisch nationalism, was more radical and it did not express any emphasis on the restoration of the German monarchy.[39] This younger generation desired to dismantle the Weimar Republic and create a new radical and strong state based upon a martial ruling ethic that could revive the "Spirit of 1914" which was associated with German national unity (Volksgemeinschaft).[39]

The Nazis, the far-right monarchists, the reactionary German National People's Party (DNVP) and others, such as monarchist officers in the German Army and several prominent industrialists, formed an alliance in opposition to the Weimar Republic on 11 October 1931 in Bad Harzburg, officially known as the "National Front", but commonly referred to as the Harzburg Front.[40] The Nazis stated that the alliance was purely tactical and they continued to have differences with the DNVP. After the elections of July 1932, the alliance broke down when the DNVP lost many of its seats in the Reichstag. The Nazis denounced them as "an insignificant heap of reactionaries".[41] The DNVP responded by denouncing the Nazis for their "socialism", their street violence and the "economic experiments" that would take place if the Nazis ever rose to power.[42] However, amidst an inconclusive political situation in which conservative politicians Franz von Papen and Kurt von Schleicher were unable to form stable governments without the Nazis, Papen proposed to President Hindenburg to appoint Hitler as Chancellor at the head of a government formed primarily of conservatives, with only three Nazi ministers.[43][44] Hindenburg did so, and contrary to the expectations of Papen and the DNVP, Hitler was soon able to establish a Nazi one-party dictatorship.[45]

Kaiser Wilhelm II, who was pressured to abdicate the throne and flee into exile amidst an attempted communist revolution in Germany, initially supported the Nazi Party. His four sons, including Prince Eitel Friedrich and Prince Oskar, became members of the Nazi Party in hopes that in exchange for their support, the Nazis would permit the restoration of the monarchy.[46] Hitler dismissed the possibility of a restored monarchy, calling it "idiotic."[47] Wilhelm grew to distrust Hitler and was appalled at the Kristallnacht of 9–10 November 1938, stating, "For the first time, I am ashamed to be a German."[48] The former German emperor also denounced the Nazis as a "bunch of shirted gangsters" and "a mob … led by a thousand liars or fanatics."[49]

There were factions within the Nazi Party, both conservative and radical.[50] The conservative Nazi Hermann Göring urged Hitler to conciliate with capitalists and reactionaries.[50] Other prominent conservative Nazis included Heinrich Himmler and Reinhard Heydrich.[51] Meanwhile, the radical Nazi Joseph Goebbels opposed capitalism, viewing it as having Jews at its core and he stressed the need for the party to emphasise both a proletarian and a national character. Those views were shared by Otto Strasser, who later left the Nazi Party and formed the Black Front in the belief that Hitler had allegedly betrayed the party's socialist goals by endorsing capitalism.[50]

When the Nazi Party emerged from obscurity to become a major political force after 1929, the conservative faction rapidly gained more influence, as wealthy donors took an interest in the Nazis as a potential bulwark against communism.[52] The Nazi Party had previously been financed almost entirely from membership dues, but after 1929 its leadership began actively seeking donations from German industrialists, and Hitler began holding dozens of fundraising meetings with business leaders.[53] In the midst of the Great Depression, facing the possibility of economic ruin on the one hand and a Communist or Social Democrat government on the other hand, German business increasingly turned to Nazism as offering a way out of the situation, by promising a state-driven economy that would support, rather than attack, existing business interests.[54] By January 1933, the Nazi Party had secured the support of important sectors of German industry, mainly among the steel and coal producers, the insurance business, and the chemical industry.[55]

Large segments of the Nazi Party, particularly among the members of the Sturmabteilung (SA), were committed to the party's official socialist, revolutionary and anti-capitalist positions and expected both a social and an economic revolution when the party gained power in 1933.[56] In the period immediately before the Nazi seizure of power, there were even Social Democrats and Communists who switched sides and became known as "Beefsteak Nazis": brown on the outside and red inside.[57] The leader of the SA, Ernst Röhm, pushed for a "second revolution" (the "first revolution" being the Nazis' seizure of power) that would enact socialist policies. Furthermore, Röhm desired that the SA absorb the much smaller German Army into its ranks under his leadership.[56] Once the Nazis achieved power, Röhm's SA was directed by Hitler to violently suppress the parties of the left, but they also began attacks against individuals deemed to be associated with conservative reaction.[58] Hitler saw Röhm's independent actions as violating and possibly threatening his leadership, as well as jeopardising the regime by alienating the conservative President Paul von Hindenburg and the conservative-oriented German Army.[59] This resulted in Hitler purging Röhm and other radical members of the SA in 1934, in what came to be known as the Night of the Long Knives.[59]

Before he joined the Bavarian Army to fight in World War I, Hitler had lived a bohemian lifestyle as a petty street watercolour artist in Vienna and Munich and he maintained elements of this lifestyle later on, going to bed very late and rising in the afternoon, even after he became Chancellor and then Führer.[60] After the war, his battalion was absorbed by the Bavarian Soviet Republic from 1918 to 1919, where he was elected Deputy Battalion Representative. According to historian Thomas Weber, Hitler attended the funeral of communist Kurt Eisner (a German Jew), wearing a black mourning armband on one arm and a red communist armband on the other,[61] which he took as evidence that Hitler's political beliefs had not yet solidified.[61] In Mein Kampf, Hitler never mentioned any service with the Bavarian Soviet Republic and he stated that he became an antisemite in 1913 during his years in Vienna. This statement has been disputed by the contention that he was not an antisemite at that time,[62] even though it is well established that he read many antisemitic tracts and journals during that time and admired Karl Lueger, the antisemitic mayor of Vienna.[63] Hitler altered his political views in response to the signing of the Treaty of Versailles in June 1919 and it was then that he became an antisemitic, German nationalist.[62]

Hitler expressed opposition to capitalism, regarding it as having Jewish origins and accusing capitalism of holding nations ransom to the interests of a parasitic cosmopolitan rentier class.[64] He also expressed opposition to communism and egalitarian forms of socialism, arguing that inequality and hierarchy are beneficial to the nation.[65] He believed that communism was invented by the Jews to weaken nations by promoting class struggle.[66] After his rise to power, Hitler took a pragmatic position on economics, accepting private property and allowing capitalist private enterprises to exist so long as they adhered to the goals of the Nazi state, but not tolerating enterprises that he saw as being opposed to the national interest.[50]

German business leaders disliked Nazi ideology but came to support Hitler, because they saw the Nazis as a useful ally to promote their interests.[67] Business groups made significant financial contributions to the Nazi Party both before and after the Nazi seizure of power, in the hope that a Nazi dictatorship would eliminate the organised labour movement and the left-wing parties.[68] Hitler actively sought to gain the support of business leaders by arguing that private enterprise is incompatible with democracy.[69]

Although he opposed communist ideology, Hitler publicly praised the Soviet Union's leader Joseph Stalin and Stalinism on numerous occasions.[70] Hitler commended Stalin for seeking to purify the Communist Party of the Soviet Union of Jewish influences, noting Stalin's purging of Jewish communists such as Leon Trotsky, Grigory Zinoviev, Lev Kamenev and Karl Radek.[71] While Hitler had always intended to bring Germany into conflict with the Soviet Union so he could gain Lebensraum ("living space"), he supported a temporary strategic alliance between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union to form a common anti-liberal front so they could defeat liberal democracies, particularly France.[70]

Hitler admired the British Empire and its colonial system as living proof of Germanic superiority over "inferior" races and saw the United Kingdom as Germany's natural ally.[72][73] He wrote in Mein Kampf: "For a long time to come there will be only two Powers in Europe with which it may be possible for Germany to conclude an alliance. These Powers are Great Britain and Italy."[73]

Origins

The historical roots of Nazism are to be found in various elements of European political culture which were in circulation in the intellectual capitals of the continent, what Joachim Fest called the "scrapheap of ideas" prevalent at the time.[74][75] In Hitler and the Collapse of the Weimar Republic, historian Martin Broszat points out that

[A]lmost all essential elements of ... Nazi ideology were to be found in the radical positions of ideological protest movements [in pre-1914 Germany]. These were: a virulent anti-Semitism, a blood-and-soil ideology, the notion of a master race, [and] the idea of territorial acquisition and settlement in the East. These ideas were embedded in a popular nationalism which was vigorously anti-modernist, anti-humanist and pseudo-religious.[75]

Brought together, the result was an anti-intellectual and politically semi-illiterate ideology lacking cohesion, a product of mass culture which allowed its followers emotional attachment and offered a simplified and easily-digestible world-view based on a political mythology for the masses.[75]

Völkisch nationalism

Adolf Hitler himself along with other members of the National Socialist German Workers' Party (German: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei, NSDAP) in the Weimar Republic (1918–1933) were greatly influenced by several 19th- and early 20th-century thinkers and proponents of philosophical, onto-epistemic, and theoretical perspectives on ecological anthropology, scientific racism, holistic science, and organicism regarding the constitution of complex systems and theorization of organic-racial societies.[76][77][78][79] In particular, one of the most significant ideological influences on the Nazis was the 19th-century German nationalist philosopher Johann Gottlieb Fichte, whose works had served as an inspiration to Hitler and other Nazi Party members, and whose ideas were implemented among the philosophical and ideological foundations of Nazi-oriented Völkisch nationalism.[77]

Fichte's works served as an inspiration to Hitler and other Nazi Party members, including Dietrich Eckart and Arnold Fanck.[77][80] In Speeches to the German Nation (1808), written amid the First French Empire's occupation of Berlin during the Napoleonic Wars, Fichte called for a German national revolution against the French Imperial Army occupiers, making passionate public speeches, arming his students for battle against the French and stressing the need for action by the German nation so it could free itself.[81] Fichte's German nationalism was populist and opposed to traditional elites, spoke of the need for a "People's War" (Volkskrieg) and put forth concepts similar to those which the Nazis adopted.[81] Fichte promoted German exceptionalism and stressed the need for the German nation to purify itself (including purging the German language of French words, a policy that the Nazis undertook upon their rise to power).[81]

Another important figure in pre-Nazi völkisch thinking was Wilhelm Heinrich Riehl, whose work—Land und Leute (Land and People, written between 1857 and 1863)—collectively tied the organic German Volk to its native landscape and nature, a pairing which stood in stark opposition to the mechanical and materialistic civilisation which was then developing as a result of industrialisation.[82] Geographers Friedrich Ratzel and Karl Haushofer borrowed from Riehl's work as did Nazi ideologues Alfred Rosenberg and Paul Schultze-Naumburg, both of whom employed some of Riehl's philosophy in arguing that "each nation-state was an organism that required a particular living space in order to survive".[83] Riehl's influence is overtly discernible in the Blut und Boden (Blood and Soil) philosophy introduced by Oswald Spengler, which the Nazi agriculturalist Walther Darré and other prominent Nazis adopted.[84][85]

Völkisch nationalism denounced soulless materialism, individualism and secularised urban industrial society, while advocating a "superior" society based on ethnic German "folk" culture and German "blood".[86] It denounced foreigners and foreign ideas and declared that Jews, Freemasons and others were "traitors to the nation" and unworthy of inclusion.[87] Völkisch nationalism saw the world in terms of natural law and romanticism and it viewed societies as organic, extolling the virtues of rural life, condemning the neglect of tradition and the decay of morals, denounced the destruction of the natural environment and condemned "cosmopolitan" cultures such as Jews and Romani.[88]

The first party that attempted to combine nationalism and socialism was the (Austria-Hungary) German Workers' Party, which predominantly aimed to solve the conflict between the Austrian Germans and the Czechs in the multi-ethnic Austrian Empire, then part of Austria-Hungary.[89] In 1896 the German politician Friedrich Naumann formed the National-Social Association which aimed to combine German nationalism and a non-Marxist form of socialism together; the attempt turned out to be futile and the idea of linking nationalism with socialism quickly became equated with antisemites, extreme German nationalists and the völkisch movement in general.[37]

During the era of the German Empire, völkisch nationalism was overshadowed by both Prussian patriotism and the federalist tradition of its various component states.[90] The events of World War I, including the end of the Prussian monarchy in Germany, resulted in a surge of revolutionary völkisch nationalism.[91] The Nazis supported such revolutionary völkisch nationalist policies[90] and they claimed that their ideology was influenced by the leadership and policies of German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck, who was instrumental in founding the German Empire.[92] The Nazis declared that they were dedicated to continuing the process of creating a unified German nation state that Bismarck had begun and desired to achieve.[93] While Hitler was supportive of Bismarck's creation of the German Empire, he was critical of Bismarck's moderate domestic policies.[94] On the issue of Bismarck's support of a Kleindeutschland ("Lesser Germany", excluding Austria) versus the Pan-German Großdeutschland ("Greater Germany") which the Nazis advocated, Hitler stated that Bismarck's attainment of Kleindeutschland was the "highest achievement" Bismarck could have achieved "within the limits possible at that time".[95] In Mein Kampf, Hitler presented himself as a "second Bismarck".[96]

During his youth in Austria, Hitler was politically influenced by Austrian Pan-Germanist proponent Georg Ritter von Schönerer, who advocated radical German nationalism, antisemitism, anti-Catholicism, anti-Slavic sentiment and anti-Habsburg views.[97] From von Schönerer and his followers, Hitler adopted for the Nazi movement the Heil greeting, the Führer title and the model of absolute party leadership.[97] Hitler was also impressed by the populist antisemitism and the anti-liberal bourgeois agitation of Karl Lueger, who as the mayor of Vienna during Hitler's time in the city used a rabble-rousing style of oratory that appealed to the wider masses.[98] Unlike von Schönerer, Lueger was not a German nationalist and instead was a pro-Catholic Habsburg supporter and only used German nationalist notions occasionally for his own agenda.[98] Although Hitler praised both Lueger and Schönerer, he criticised the former for not applying a racial doctrine against the Jews and Slavs.[99]

Racial theories and antisemitism

The concept of the Aryan race, which the Nazis promoted, stems from racial theories asserting that Europeans are the descendants of Indo-Iranian settlers, people of ancient India and ancient Persia.[100] Proponents of this theory based their assertion on the fact that words in European languages and words in Indo-Iranian languages have similar pronunciations and meanings.[100] Johann Gottfried Herder argued that the Germanic peoples held close racial connections to the ancient Indians and the ancient Persians, who he claimed were advanced peoples that possessed a great capacity for wisdom, nobility, restraint and science.[100] Contemporaries of Herder used the concept of the Aryan race to draw a distinction between what they deemed to be "high and noble" Aryan culture versus that of "parasitic" Semitic culture.[100]

Notions of white supremacy and Aryan racial superiority were combined in the 19th century, with white supremacists maintaining the belief that certain groups of white people were members of an Aryan "master race" that is superior to other races and particularly superior to the Semitic race, which they associated with "cultural sterility".[100] Arthur de Gobineau, a French racial theorist and aristocrat, blamed the fall of the ancien régime in France on racial degeneracy caused by racial intermixing, which he argued had destroyed the purity of the Aryan race, a term which he only reserved for Germanic people.[101][102] Gobineau's theories, which attracted a strong following in Germany,[101] emphasised the existence of an irreconcilable polarity between Aryan (Germanic) and Jewish cultures.[100]

Aryan mysticism claimed that Christianity originated in Aryan religious traditions, and that Jews had usurped the legend from Aryans.[100] Houston Stewart Chamberlain, an English-born German proponent of racial theory, supported notions of Germanic supremacy and antisemitism in Germany.[101] Chamberlain's work, The Foundations of the Nineteenth Century (1899), praised Germanic peoples for their creativity and idealism while asserting that the Germanic spirit was threatened by a "Jewish" spirit of selfishness and materialism.[101] Chamberlain used his thesis to promote monarchical conservatism while denouncing democracy, liberalism and socialism.[101] The book became popular, especially in Germany.[101] Chamberlain stressed a nation's need to maintain its racial purity in order to prevent its degeneration and argued that racial intermingling with Jews should never be permitted.[101] In 1923, Chamberlain met Hitler, whom he admired as a leader of the rebirth of the free spirit.[103] Madison Grant's work The Passing of the Great Race (1916) advocated Nordicism and proposed that a eugenics program should be implemented in order to preserve the purity of the Nordic race. After reading the book, Hitler called it "my Bible".[104]

In Germany, the belief that Jews were economically exploiting Germans became prominent due to the ascendancy of many wealthy Jews into prominent positions upon the unification of Germany in 1871.[105] From 1871 to the early 20th century, German Jews were overrepresented in Germany's upper and middle classes while they were underrepresented in Germany's lower classes, particularly in the fields of agricultural and industrial labour.[106] German Jewish financiers and bankers played a key role in fostering Germany's economic growth from 1871 to 1913 and they benefited enormously from this boom. In 1908, amongst the twenty-nine wealthiest German families with aggregate fortunes of up to 55 million marks at the time, five were Jewish and the Rothschilds were the second wealthiest German family.[107] The predominance of Jews in Germany's banking, commerce and industry sectors during this time period was very high, even though Jews were estimated to account for only 1% of the population of Germany.[105] The overrepresentation of Jews in these areas fuelled resentment among non-Jewish Germans during periods of economic crisis.[106] The 1873 stock market crash and the ensuing depression resulted in a spate of attacks on alleged Jewish economic dominance in Germany and antisemitism increased.[106] During this time period, in the 1870s, German völkisch nationalism began to adopt antisemitic and racist themes and it was also adopted by a number of radical right political movements.[108]

Radical antisemitism was promoted by prominent advocates of völkisch nationalism, including Eugen Diederichs, Paul de Lagarde and Julius Langbehn.[88] De Lagarde called the Jews a "bacillus, the carriers of decay ... who pollute every national culture ... and destroy all faiths with their materialistic liberalism" and he called for the extermination of the Jews.[109] Langbehn called for a war of annihilation against the Jews, and his genocidal policies were later published by the Nazis and given to soldiers on the front during World War II.[109] One antisemitic ideologue of the period, Friedrich Lange, even used the term "National Socialism" to describe his own anti-capitalist take on the völkisch nationalist template.[110]

Johann Gottlieb Fichte accused Jews in Germany of having been and inevitably of continuing to be a "state within a state" that threatened German national unity.[81] Fichte promoted two options in order to address this, his first one being the creation of a Jewish state in Palestine so the Jews could be impelled to leave Europe.[111] His second option was violence against Jews and he said that the goal of the violence would be "to cut off all their heads in one night, and set new ones on their shoulders, which should not contain a single Jewish idea".[111]

The Protocols of the Elders of Zion (1912) is an antisemitic forgery created by the secret service of the Russian Empire, the Okhrana. Many antisemites believed it was real and thus it became widely popular after World War I.[112] The Protocols claimed that there was a secret international Jewish conspiracy to take over the world.[113] Hitler had been introduced to The Protocols by Alfred Rosenberg and from 1920 onwards he focused his attacks by claiming that Judaism and Marxism were directly connected, that Jews and Bolsheviks were one and the same and that Marxism was a Jewish ideology-this became known as "Jewish Bolshevism".[114] Hitler believed that The Protocols were authentic.[115]

During his life in Vienna between 1907 and 1913, Hitler became fervently anti-Slavic.[116][117][118][119] Prior to the Nazi ascension to power, Hitler often blamed moral degradation on Rassenschande ("racial defilement"), a way to assure his followers of his continuing antisemitism, which had been toned down for popular consumption.[120] Prior to the induction of the Nuremberg Race Laws in 1935 by the Nazis, many German nationalists such as Roland Freisler strongly supported laws to ban Rassenschande between Aryans and Jews as racial treason.[120] Even before the laws were officially passed, the Nazis banned sexual relations and marriages between party members and Jews.[121] Party members found guilty of Rassenschande were severely punished; some party members were even sentenced to death.[122]

The Nazis claimed that Bismarck was unable to complete German national unification because Jews had infiltrated the German parliament and they claimed that their abolition of parliament had ended this obstacle to unification.[92] Using the stab-in-the-back myth, the Nazis accused Jews—and other populations who it considered non-German—of possessing extra-national loyalties, thereby exacerbating German antisemitism about the Judenfrage (the Jewish Question), the far-right political canard which was popular when the ethnic völkisch movement and its politics of Romantic nationalism for establishing a Großdeutschland was strong.[123][124]

Nazism's racial policy positions may have developed from the views of important biologists of the 19th century, including French biologist Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, through Ernst Haeckel's idealist version of Lamarckism and the father of genetics, German botanist Gregor Mendel.[125] Haeckel's works were later condemned by the Nazis as inappropriate for "National-Socialist formation and education in the Third Reich". This may have been because of his "monist" atheistic, materialist philosophy, which the Nazis disliked, along with his friendliness to Jews, opposition to militarism and support altruism, with one Nazi official calling for them to be banned.[126] Unlike Darwinian theory, Lamarckian theory officially ranked races in a hierarchy of evolution from apes while Darwinian theory did not grade races in a hierarchy of higher or lower evolution from apes, but simply stated that all humans as a whole had progressed in their evolution from apes.[125] Many Lamarckians viewed "lower" races as having been exposed to debilitating conditions for too long for any significant "improvement" of their condition to take place in the near future.[127] Haeckel used Lamarckian theory to describe the existence of interracial struggle and put races on a hierarchy of evolution, ranging from wholly human to subhuman.[125]

Mendelian inheritance, or Mendelism, was supported by the Nazis, as well as by mainstream eugenicists of the time. The Mendelian theory of inheritance declared that genetic traits and attributes were passed from one generation to another.[128] Eugenicists used Mendelian inheritance theory to demonstrate the transfer of biological illness and impairments from parents to children, including mental disability, whereas others also used Mendelian theory to demonstrate the inheritance of social traits, with racialists claiming a racial nature behind certain general traits such as inventiveness or criminal behaviour.[129]

Use of the American racist model

Hitler and other Nazi legal theorists were inspired by America's institutional racism and saw it as the model to follow. In particular, they saw it as a model for the expansion of territory and the elimination of indigenous inhabitants therefrom, for laws denying full citizenship for African Americans, which they wanted to implement also against Jews, and for racist immigration laws banning some races. In Mein Kampf, Hitler extolled America as the only contemporary example of a country with racist ("völkisch") citizenship statutes in the 1920s, and Nazi lawyers made use of the American models in crafting laws for Nazi Germany.[130] U.S. citizenship laws and anti-miscegenation laws directly inspired the two principal Nuremberg Laws—the Citizenship Law and the Blood Law.[130]

Response to World War I and Italian Fascism

During World War I, German sociologist Johann Plenge spoke of the rise of a "National Socialism" in Germany within what he termed the "ideas of 1914" that were a declaration of war against the "ideas of 1789" (the French Revolution).[131] According to Plenge, the "ideas of 1789" which included the rights of man, democracy, individualism and liberalism were being rejected in favour of "the ideas of 1914" which included the "German values" of duty, discipline, law and order.[131] Plenge believed that ethnic solidarity (Volksgemeinschaft) would replace class division and that "racial comrades" would unite to create a socialist society in the struggle of "proletarian" Germany against "capitalist" Britain.[131] He believed that the "Spirit of 1914" manifested itself in the concept of the "People's League of National Socialism".[132] This National Socialism was a form of state socialism that rejected the "idea of boundless freedom" and promoted an economy that would serve the whole of Germany under the leadership of the state.[132] This National Socialism was opposed to capitalism due to the components that were against "the national interest" of Germany, but insisted that National Socialism would strive for greater efficiency in the economy.[132] Plenge advocated an authoritarian, rational ruling elite to develop National Socialism through a hierarchical technocratic state,[133] and his ideas were part of the basis of Nazism.[131]

Oswald Spengler, a German cultural philosopher, was a major influence on Nazism, although after 1933 he became alienated from Nazism and was later condemned by the Nazis for criticising Adolf Hitler.[134] Spengler's conception of national socialism and a number of his political views were shared by the Nazis and the Conservative Revolutionary movement.[135] Spengler's views were also popular amongst Italian Fascists, including Benito Mussolini.[136]

Spengler's book The Decline of the West (1918), written during the final months of World War I, addressed the supposed decadence of modern European civilisation, which he claimed was caused by atomising and irreligious individualisation and cosmopolitanism.[134] Spengler's major thesis was that a law of historical development of cultures existed involving a cycle of birth, maturity, ageing and death when it reaches its final form of civilisation.[134] Upon reaching the point of civilisation, a culture will lose its creative capacity and succumb to decadence until the emergence of "barbarians" creates a new epoch.[134] Spengler considered the Western world as having succumbed to decadence of intellect, money, cosmopolitan urban life, irreligious life, atomised individualisation and believed that it was at the end of its biological and "spiritual" fertility.[134] He believed that the "young" German nation as an imperial power would inherit the legacy of Ancient Rome, lead a restoration of value in "blood" and instinct, while the ideals of rationalism would be revealed as absurd.[134]

Spengler's notions of "Prussian socialism" as described in his book Preussentum und Sozialismus ("Prussiandom and Socialism", 1919), influenced Nazism and the Conservative Revolutionary movement.[135] Spengler wrote: "The meaning of socialism is that life is controlled not by the opposition between rich and poor, but by the rank that achievement and talent bestow. That is our freedom, freedom from the economic despotism of the individual".[135] Spengler adopted the anti-English ideas addressed by Plenge and Sombart during World War I that condemned English liberalism and English parliamentarianism while advocating a national socialism that was free from Marxism and that would connect the individual to the state through corporatist organisation.[134] Spengler claimed that socialistic Prussian characteristics existed across Germany, including creativity, discipline, concern for the greater good, productivity and self-sacrifice.[137] He prescribed war as a necessity by saying: "War is the eternal form of higher human existence and states exist for war: they are the expression of the will to war".[138]

Spengler's definition of socialism did not advocate a change to property relations.[135] He denounced Marxism for seeking to train the proletariat to "expropriate the expropriator", the capitalist and then to let them live a life of leisure on this expropriation.[140] He claimed that "Marxism is the capitalism of the working class" and not true socialism.[140] According to Spengler, true socialism would be in the form of corporatism, stating that "local corporate bodies organised according to the importance of each occupation to the people as a whole; higher representation in stages up to a supreme council of the state; mandates revocable at any time; no organised parties, no professional politicians, no periodic elections".[141]

Wilhelm Stapel, an antisemitic German intellectual, used Spengler's thesis on the cultural confrontation between Jews as whom Spengler described as a Magian people versus Europeans as a Faustian people.[142] Stapel described Jews as a landless nomadic people in pursuit of an international culture whereby they can integrate into Western civilisation.[142] As such, Stapel claims that Jews have been attracted to "international" versions of socialism, pacifism or capitalism because as a landless people the Jews have transgressed various national cultural boundaries.[142]

For all of Spengler's influence on the movement, he was opposed to its antisemitism. He wrote in his personal papers "[H]ow much envy of the capability of other people in view of one's lack of it lies hidden in anti-Semitism!" as well as "[W]hen one would rather destroy business and scholarship than see Jews in them, one is an ideologue, i.e., a danger for the nation. Idiotic."[143]

Arthur Moeller van den Bruck was initially the dominant figure of the Conservative Revolutionaries influenced Nazism.[144] He rejected reactionary conservatism while proposing a new state that he coined the "Third Reich", which would unite all classes under authoritarian rule.[145] Van den Bruck advocated a combination of the nationalism of the right and the socialism of the left.[146]

Fascism was a major influence on Nazism. The seizure of power by Italian Fascist leader Benito Mussolini in the March on Rome in 1922 drew admiration by Hitler, who less than a month later had begun to model himself and the Nazi Party upon Mussolini and the Fascists.[147] Hitler presented the Nazis as a form of German fascism.[148][149] In November 1923, the Nazis attempted a "March on Berlin" modelled after the March on Rome, which resulted in the failed Beer Hall Putsch in Munich.[150]

Hitler spoke of Nazism being indebted to the success of Fascism's rise to power in Italy.[151] In a private conversation in 1941, Hitler said that "the brown shirt would probably not have existed without the black shirt", the "brown shirt" referring to the Nazi militia and the "black shirt" referring to the Fascist militia.[151] He also said in regards to the 1920s: "If Mussolini had been outdistanced by Marxism, I don't know whether we could have succeeded in holding out. At that period National Socialism was a very fragile growth".[151]

Other Nazis—especially those at the time associated with the party's more radical wing such as Gregor Strasser, Joseph Goebbels and Heinrich Himmler—rejected Italian Fascism, accusing it of being too conservative or capitalist.[152] Alfred Rosenberg condemned Italian Fascism for being racially confused and having influences from philosemitism.[153] Strasser criticised the policy of Führerprinzip as being created by Mussolini and considered its presence in Nazism as a foreign imported idea.[154] Throughout the relationship between Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy, a number of lower-ranking Nazis scornfully viewed fascism as a conservative movement that lacked a full revolutionary potential.[154]

Ideology and programme

In his book The Hitler State (Der Staat Hitlers), historian Martin Broszat writes:

...National Socialism was not primarily an ideological and programmatic, but a charismatic movement, whose ideology was incorporated in the Führer, Hitler, and which would have lost all its power to integrate without him. ... [T]he abstract, utopian and vague National Socialistic ideology only achieved what reality and certainty it had through the medium of Hitler.

Thus, any explication of the ideology of Nazism must be descriptive, as it was not generated primarily from first principles, but was the result of numerous factors, including Hitler's strongly-held personal views, some parts of the 25-point plan, the general goals of the völkische and nationalist movements, and the conflicts between Nazi Party functionaries who battled "to win [Hitler] over to their respective interpretations of [National Socialism]." Once the Party had been purged of divergant influences such as Strasserism, Hitler was accepted by the Party's leadership as the "supreme authority to rule on ideological matters".[155]

Nazi ideology was based on a bio-geo-political "Weltanschauung" (worldview), advocating territorial expansionism to cultivate what it viewed as a "purified and homogeneous Aryan population." Nazi regime's policies were shaped by the integration of biopolitics and geopolitics within the Hitlerian worldview, amalgamating spatial theory, practice, and imagination with biopolitics. In Hitlerism, the concepts of space and race were not separate but existed in tension, forming a distinct bio-geo-political framework at the core of the Nazi project. This ideology viewed German territorial conquests and extermination of those ethnic groups it dehumanised as "untermensch" as part of a biopolitical process to establish an ideal German community.[156][157]

Nationalism and racialism

Nazism emphasised German nationalism, including both irredentism and expansionism. Nazism held racial theories based upon a belief in the existence of an Aryan master race that was superior to all other races. The Nazis emphasised the existence of racial conflict between the Aryan race and others—particularly Jews, whom the Nazis viewed as a mixed race that had infiltrated multiple societies and was responsible for exploitation and repression of the Aryan race. The Nazis also categorised Slavs as Untermensch (sub-human).[158]

Wolfgang Bialas argues that the Nazis' sense of morality could be described as a form of procedural virtue ethics, as it demanded unconditional obedience to absolute virtues with the attitude of social engineering and replaced common sense intuitions with an ideological catalogue of virtues and commands. The ideal Nazi new man was to be race-conscious and an ideologically dedicated warrior who would commit actions for the sake of the German race while at the same time convinced he was doing the right thing and acting morally. The Nazis believed an individual could only develop their capabilities and individual characteristics within the framework of the individual's racial membership; the race one belonged to determined whether or not one was worthy of moral care. The Christian concept of self-denial was to be replaced with the idea of self-assertion towards those deemed inferior. Natural selection and the struggle for existence were declared by the Nazis to be the most divine laws; peoples and individuals deemed inferior were said to be incapable of surviving without those deemed superior, yet by doing so they imposed a burden on the superior. Natural selection was deemed to favour the strong over the weak and the Nazis deemed that protecting those declared inferior was preventing nature from taking its course; those incapable of asserting themselves were viewed as doomed to annihilation, with the right to life being granted only to those who could survive on their own.[159]

Irredentism and expansionism

At the core of the Nazi ideology was the bio-geo-political project to acquire Lebensraum ("living space") through territorial conquests.[160] The German Nazi Party supported German irredentist claims to Austria, Alsace-Lorraine, the region of Sudetenland, and the territory known since 1919 as the Polish Corridor. A major policy of the German Nazi Party was Lebensraum for the German nation based on claims that Germany after World War I was facing an overpopulation crisis and that expansion was needed to end the country's overpopulation within existing confined territory, and provide resources necessary to its people's well-being.[161] Since the 1920s, the Nazi Party publicly promoted the expansion of Germany into territories held by the Soviet Union.[162]

In Mein Kampf, Hitler stated that Lebensraum would be acquired in Eastern Europe, especially Russia.[163] In his early years as the Nazi leader, Hitler had claimed that he would be willing to accept friendly relations with Russia on the tactical condition that Russia agree to return to the borders established by the German–Russian peace agreement of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk signed by Grigori Sokolnikov of the Russian Soviet Republic in 1918 which gave large territories held by Russia to German control in exchange for peace.[162] In 1921, Hitler had commended the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk as opening the possibility for restoration of relations between Germany and Russia by saying:

Through the peace with Russia the sustenance of Germany as well as the provision of work were to have been secured by the acquisition of land and soil, by access to raw materials, and by friendly relations between the two lands.

— Adolf Hitler[162]

From 1921 to 1922, Hitler evoked rhetoric of both the achievement of Lebensraum involving the acceptance of a territorially reduced Russia as well as supporting Russian nationalists in overthrowing the Bolsheviks and establishing a new White Russian government.[162] Hitler's attitudes changed by the end of 1922, in which he then supported an alliance of Germany with Britain to destroy Russia.[162] Hitler later declared how far he intended to expand Germany into Russia:

Asia, what a disquieting reservoir of men! The safety of Europe will not be assured until we have driven Asia back behind the Urals. No organized Russian state must be allowed to exist west of that line.

— Adolf Hitler[165]

"For the future of the German nation the 1914 frontiers are of no significance. They did not serve to protect us in the past, nor do they offer any guarantee for our defence in the future. With these frontiers the German people cannot maintain themselves as a compact unit, nor can they be assured of their maintenance. ... Against all this we, National Socialists, must stick firmly to the aim that we have set for our foreign policy; namely, that the German people must be assured the territorial area which is necessary for it to exist on this earth. ... The right to territory may become a duty when a great nation seems destined to go under unless its territory be extended. And that is particularly true when the nation in question is not some little group of negro people but the Germanic mother of all the life which has given cultural shape to the modern world."

— Adolf Hitler, — ("Mein Kampf", Volume 2, Chapter 14: "Germany's policy in Eastern Europe")[166]

Policy for Lebensraum planned mass expansion of Germany's borders to eastwards of the Ural Mountains.[165][167] Hitler planned for the "surplus" Russian population living west of the Urals to be deported to the east of the Urals.[168]

Historian Adam Tooze explains that Hitler believed that lebensraum was vital to securing American-style consumer affluence for the German people. In this light, Tooze argues that the view that the regime faced a "guns or butter" contrast is mistaken. While it is true that resources were diverted from civilian consumption to military production, Tooze explains that at a strategic level "guns were ultimately viewed as a means to obtaining more butter".[169]

While the Nazi pre-occupation with agrarian living and food production are often seen as a sign of their backwardness, Tooze explains this was in fact a major driving issue in European society for at least the last two centuries. The issue of how European societies should respond to the new global economy in food was one of the major issues facing Europe in the early 20th century. Agrarian life in Europe (except perhaps with the exception of Britain) was incredibly common—in the early 1930s, over 9 million Germans (almost a third of the work force) were still working in agriculture and many people not working in agriculture still had small allotments or otherwise grew their own food. Tooze estimates that just over half the German population in the 1930s was living in towns and villages with populations under 20,000 people. Many people in cities still had memories of rural-urban migration—Tooze thus explains that the Nazis obsessions with agrarianism were not an atavistic gloss on a modern industrial nation but a consequence of the fact that Nazism (as both an ideology and as a movement) was the product of a society still in economic transition.[170]

The Nazis obsession with food production was a consequence of the First World War. While Europe was able to avert famine with international imports, blockades brought the issue of food security back into European politics, the Allied blockade of Germany in and after World War I did not cause an outright famine but chronic malnutrition did kill an estimated 600,000 people in Germany and Austria. The economic crises of the interwar period meant that most Germans had memories of acute hunger. Thus Tooze concludes that the Nazis obsession with acquiring land was not a case of "turning back the clock" but more a refusal to accept that the result of the distribution of land, resources and population, which had resulted from the imperialist wars of the 18th and 19th centuries, should be accepted as final. While the victors of the First World War had either suitable agricultural land to population ratios or large empires (or both), allowing them to declare the issue of living space closed, the Nazis, knowing Germany lacked either of these, refused to accept that Germany's place in the world was to be a medium-sized workshop dependent upon imported food.[171]

According to Goebbels, the conquest of Lebensraum was intended as an initial step[172] towards the final goal of Nazi ideology, which was the establishment of complete German global hegemony.[173] Rudolf Hess relayed to Walter Hewel Hitler's belief that world peace could only be acquired "when one power, the racially best one, has attained uncontested supremacy". When this control would be achieved, this power could then set up for itself a world police and assure itself "the necessary living space. [...] The lower races will have to restrict themselves accordingly".[173]

Racial theories

In its racial categorisation, Nazism viewed what it called the Aryan race as the master race of the world—a race that was superior to all other races.[174] It viewed Aryans as being in racial conflict with a mixed race people, the Jews, whom the Nazis identified as a dangerous enemy of the Aryans. It also viewed a number of other peoples as dangerous to the well-being of the Aryan race. In order to preserve the perceived racial purity of the Aryan race, a set of race laws was introduced in 1935 which came to be known as the Nuremberg Laws. At first these laws only prevented sexual relations and marriages between Germans and Jews, but they were later extended to the "Gypsies, Negroes, and their bastard offspring", who were described by the Nazis as people of "alien blood".[175][176] Such relations between Aryans (cf. Aryan certificate) and non-Aryans were now punishable under the race laws as Rassenschande or "race defilement".[175] After the war began, the race defilement law was extended to include all foreigners (non-Germans).[177] At the bottom of the racial scale of non-Aryans were Jews, Romanis, Slavs[178] and blacks.[179] To maintain the "purity and strength" of the Aryan race, the Nazis eventually sought to exterminate Jews, Romani, Slavs and the physically and mentally disabled.[178][180] Other groups deemed "degenerate" and "asocial" who were not targeted for extermination, but were subjected to exclusionary treatment by the Nazi state, included homosexuals, blacks, Jehovah's Witnesses and political opponents.[180] One of Hitler's ambitions at the start of the war was to exterminate, expel or enslave most or all Slavs from Central and Eastern Europe in order to acquire living space for German settlers.[181]

A Nazi-era school textbook for German students entitled Heredity and Racial Biology for Students written by Jakob Graf described to students the Nazi conception of the Aryan race in a section titled "The Aryan: The Creative Force in Human History".[174] Graf claimed that the original Aryans developed from Nordic peoples who invaded Ancient India and launched the initial development of Aryan culture there that later spread to ancient Persia and he claimed that the Aryan presence in Persia was what was responsible for its development into an empire.[174] He claimed that ancient Greek culture was developed by Nordic peoples due to paintings of the time which showed Greeks who were tall, light-skinned, light-eyed, blond-haired people.[174] He said that the Roman Empire was developed by the Italics who were related to the Celts who were also a Nordic people.[174] He believed that the vanishing of the Nordic component of the populations in Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome led to their downfall.[174] The Renaissance was claimed to have developed in the Western Roman Empire because of the Migration Period that brought new Nordic blood to the Empire's lands, such as the presence of Nordic blood in the Lombards (referred to as Longobards in the book); that remnants of the Visigoths were responsible for the creation of the Spanish Empire; and that the heritage of the Franks, Goths and Germanic peoples in France was what was responsible for its rise as a major power.[174] He claimed that the rise of the Russian Empire was due to its leadership by people of Norman descent.[174] He described the rise of Anglo-Saxon societies in North America, South Africa and Australia as being the result of the Nordic heritage of Anglo-Saxons.[174] He concluded these points by saying: "Everywhere Nordic creative power has built mighty empires with high-minded ideas, and to this very day Aryan languages and cultural values are spread over a large part of the world, though the creative Nordic blood has long since vanished in many places".[174]

In Nazi Germany, the idea of creating a master race resulted in efforts to "purify" the Deutsche Volk through eugenics and its culmination was the compulsory sterilisation or the involuntary euthanasia of physically or mentally disabled people. After World War II, the euthanasia programme was named Action T4.[182] The ideological justification for euthanasia was Hitler's view of Sparta (11th century – 195 BC) as the original völkisch state and he praised Sparta's dispassionate destruction of congenitally deformed infants in order to maintain racial purity.[183][184] Some non-Aryans enlisted in Nazi organisations like the Hitler Youth and the Wehrmacht, including Germans of African descent[185] and Jewish descent.[186] The Nazis began to implement "racial hygiene" policies as soon as they came to power. The July 1933 "Law for the Prevention of Hereditarily Diseased Offspring" prescribed compulsory sterilisation for people with a range of conditions which were thought to be hereditary, such as schizophrenia, epilepsy, Huntington's chorea and "imbecility". Sterilization was also mandated for chronic alcoholism and other forms of social deviance.[187] An estimated 360,000 people were sterilised under this law between 1933 and 1939. Although some Nazis suggested that the programme should be extended to people with physical disabilities, such ideas had to be expressed carefully, given the fact that some Nazis had physical disabilities, one example being one of the most powerful figures of the regime, Joseph Goebbels, who had a deformed right leg.[188]

Nazi racial theorist Hans F. K. Günther argued that European peoples were divided into five races: Nordic, Mediterranean, Dinaric, Alpine and East Baltic.[11] Günther applied a Nordicist conception in order to justify his belief that Nordics were the highest in the racial hierarchy.[11] In his book Rassenkunde des deutschen Volkes (1922) ("Racial Science of the German People"), Günther recognised Germans as being composed of all five races, but emphasised the strong Nordic heritage among them.[189] Hitler read Rassenkunde des deutschen Volkes, which influenced his racial policy.[190] Gunther believed that Slavs belonged to an "Eastern race" and he warned against Germans mixing with them.[191] The Nazis described Jews as being a racially mixed group of primarily Near Eastern and Oriental racial types.[192] Because such racial groups were concentrated outside Europe, the Nazis claimed that Jews were "racially alien" to all European peoples and that they did not have deep racial roots in Europe.[192]

Günther emphasised Jews' Near Eastern racial heritage.[193] Günther identified the mass conversion of the Khazars to Judaism in the 8th century as creating the two major branches of the Jewish people: those of primarily Near Eastern racial heritage became the Ashkenazi Jews (that he called Eastern Jews) while those of primarily Oriental racial heritage became the Sephardi Jews (that he called Southern Jews).[194] Günther claimed that the Near Eastern type was composed of commercially spirited and artful traders, and that the type held strong psychological manipulation skills which aided them in trade.[193] He claimed that the Near Eastern race had been "bred not so much for the conquest and exploitation of nature as it had been for the conquest and exploitation of people".[193] Günther believed that European peoples had a racially motivated aversion to peoples of Near Eastern racial origin and their traits, and as evidence of this he showed multiple examples of depictions of satanic figures with Near Eastern physiognomies in European art.[195]

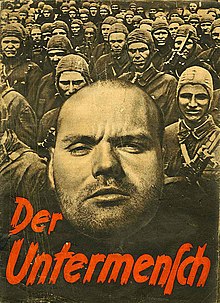

Hitler's conception of the Aryan Herrenvolk ("Aryan master race") excluded the vast majority of Slavs from Central and Eastern Europe (i.e. Poles, Russians, Ukrainians, Belarusians, etc.). They were regarded as a race of men not inclined to a higher form of civilisation, which was under an instinctive force that reverted them back to nature. The Nazis also regarded the Slavs as having dangerous Jewish and Asiatic, meaning Mongol, influences.[197] Because of this, the Nazis declared Slavs to be Untermenschen ("subhumans").[198]

Nazi anthropologists attempted to scientifically prove the historical admixture of the Slavs who lived further East and leading Nazi racial theorist Hans Günther regarded the Slavs as being primarily Nordic centuries ago but he believed that they had mixed with non-Nordic types over time.[199] Exceptions were made for a small percentage of Slavs who the Nazis saw as descended from German settlers and therefore fit to be Germanised and considered part of the Aryan master race.[200] Hitler described Slavs as "a mass of born slaves who feel the need for a master".[201] Himmler classified Slavs as "bestial untermenschen" and Jews as the "decisive leader of the Untermenschen".[202] These ideas were fervently advocated through Nazi propaganda, which had a massive impact on the indoctrination of the German population. "Der Untermenschen", a racist brochure published by the SS in 1942, has been regarded as one of the most infamous pieces of Nazi anti-Slavic propaganda.[203][204]

The Nazi notion of Slavs as inferior served as a legitimisation of their desire to create Lebensraum for Germans and other Germanic people in eastern Europe, where millions of Germans and other Germanic settlers would be moved into once those territories were conquered, while the original Slavic inhabitants were to be annihilated, removed or enslaved.[205] Nazi Germany's policy changed towards Slavs in response to military manpower shortages, forcing it to allow Slavs to serve in its armed forces within the occupied territories in spite of the fact that they were considered "subhuman".[206]

Hitler declared that racial conflict against Jews was necessary in order to save Germany from suffering under them and he dismissed concerns that the conflict with them was inhumane and unjust:

We may be inhumane, but if we rescue Germany we have achieved the greatest deed in the world. We may work injustice, but if we rescue Germany then we have removed the greatest injustice in the world. We may be immoral, but if our people is rescued we have opened the way for morality.[207]

Nazi propagandist Joseph Goebbels frequently employed antisemitic rhetoric to underline this view: "The Jew is the enemy and the destroyer of the purity of blood, the conscious destroyer of our race."[208]

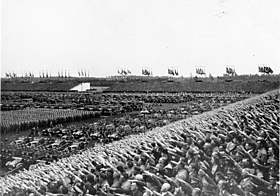

Social class

National Socialist politics was based on competition and struggle as its organising principle, and the Nazis believed that "human life consisted of eternal struggle and competition and derived its meaning from struggle and competition."[209] The Nazis saw this eternal struggle in military terms, and advocated a society organised like an army in order to achieve success. They promoted the idea of a national-racial "people's community" (Volksgemeinschaft) in order to accomplish "the efficient prosecution of the struggle against other peoples and states."[210] Like an army, the Volksgemeinschaft was meant to consist of a hierarchy of ranks or classes of people, some commanding and others obeying, all working together for a common goal.[210] This concept was rooted in the writings of 19th century völkisch authors who glorified medieval German society, viewing it as a "community rooted in the land and bound together by custom and tradition," in which there was neither class conflict nor selfish individualism.[211] The Nazis concept of the volksgemeinschaft appealed to many, as it was seen as it seemed at once to affirm a commitment to a new type of society for the modern age yet also offer protection from the tensions and insecurities of modernisation. It would balance individual achievement with group solidarity and cooperation with competition. Stripped of its ideological overtones, the Nazi vision of modernisation without internal conflict and a political community that offered both security and opportunity was so potent a vision of the future that many Germans were willing to overlook its racist and anti-Semitic essence.[212]

Nazism rejected the Marxist concept of class conflict, and it praised both German capitalists and German workers as essential to the Volksgemeinschaft. In the Volksgemeinschaft, social classes would continue to exist, but there would be no class conflict between them.[213] Hitler said that "the capitalists have worked their way to the top through their capacity, and as the basis of this selection, which again only proves their higher race, they have a right to lead."[214] German business leaders co-operated with the Nazis during their rise to power and received substantial benefits from the Nazi state after it was established, including high profits and state-sanctioned monopolies and cartels.[215] Large celebrations and symbolism were used extensively to encourage those engaged in physical labour on behalf of Germany, with leading National Socialists often praising the "honour of labour", which fostered a sense of community (Gemeinschaft) for the German people and promoted solidarity towards the Nazi cause.[216] To win workers away from Marxism, Nazi propaganda sometimes presented its expansionist foreign policy goals as a "class struggle between nations."[214] Bonfires were made of school children's differently coloured caps as symbolic of the unity of different social classes.[217]

In 1922, Hitler disparaged other nationalist and racialist political parties as disconnected from the mass populace, especially lower and working-class young people:

The racialists were not capable of drawing the practical conclusions from correct theoretical judgements, especially in the Jewish Question. In this way, the German racialist movement developed a similar pattern to that of the 1880s and 1890s. As in those days, its leadership gradually fell into the hands of highly honourable, but fantastically naïve men of learning, professors, district counsellors, schoolmasters, and lawyers—in short a bourgeois, idealistic, and refined class. It lacked the warm breath of the nation's youthful vigour.[218]

Nevertheless, the Nazi Party's voter base consisted mainly of farmers and the middle class, including groups such as Weimar government officials, school teachers, doctors, clerks, self-employed businessmen, salesmen, retired officers, engineers, and students.[219] Their demands included lower taxes, higher prices for food, restrictions on department stores and consumer co-operatives, and reductions in social services and wages.[220] The need to maintain the support of these groups made it difficult for the Nazis to appeal to the working class, since the working class often had opposite demands.[220]

From 1928 onward, the Nazi Party's growth into a large national political movement was dependent on middle class support, and on the public perception that it "promised to side with the middle classes and to confront the economic and political power of the working class."[221] The financial collapse of the white collar middle-class of the 1920s figures much in their strong support of Nazism.[222] Although the Nazis continued to make appeals to "the German worker", historian Timothy Mason concludes that "Hitler had nothing but slogans to offer the working class."[223] Historians Conan Fischer and Detlef Mühlberger argue that while the Nazis were primarily rooted in the lower middle class, they were able to appeal to all classes in society and that while workers were generally underrepresented, they were still a substantial source of support for the Nazis.[224][225] H.L. Ansbacher argues that the working-class soldiers had the most faith in Hitler out of any occupational group in Germany.[226]

The Nazis also established a norm that every worker should be semi-skilled, which was not simply rhetorical; the number of men leaving school to enter the work force as unskilled labourers fell from 200,000 in 1934 to 30,000 in 1939. For many working-class families, the 1930s and 1940s were a time of social mobility; not in the sense of moving into the middle class but rather moving within the blue-collar skill hierarchy.[227] Overall, the experience of workers varied considerably under Nazism. Workers' wages did not increase much during Nazi rule, as the government feared wage-price inflation and thus wage growth was limited. Prices for food and clothing rose, though costs for heating, rent and light decreased. Skilled workers were in shortage from 1936 onward, meaning that workers who engaged in vocational training could look forward to considerably higher wages. Benefits provided by the Labour Front were generally positively received, even if workers did not always buy in to propaganda about the volksgemeinschaft. Workers welcomed opportunities for employment after the harsh years of the Great Depression, creating a common belief that the Nazis had removed the insecurity of unemployment. Workers who remained discontented risked the Gestapo's informants. Ultimately, the Nazis faced a conflict between their rearmament program, which by necessity would require material sacrifices from workers (longer hours and a lower standard of living), versus a need to maintain the confidence of the working class in the regime. Hitler was sympathetic to the view that stressed taking further measures for rearmament but he did not fully implement the measures required for it in order to avoid alienating the working class.[228]

While the Nazis had substantial support amongst the middle-class, they often attacked traditional middle-class values and Hitler personally held great contempt for them. This was because the traditional image of the middle class was one that was obsessed with personal status, material attainment and quiet, comfortable living, which was in opposition to the Nazism's ideal of a New Man. The Nazis' New Man was envisioned as a heroic figure who rejected a materialistic and private life for a public life and a pervasive sense of duty, willing to sacrifice everything for the nation. Despite the Nazis' contempt for these values, they were still able to secure millions of middle-class votes. Hermann Beck argues that while some members of the middle-class dismissed this as mere rhetoric, many others in some ways agreed with the Nazis—the defeat of 1918 and the failures of the Weimar period caused many middle-class Germans to question their own identity, thinking their traditional values to be anachronisms and agreeing with the Nazis that these values were no longer viable. While this rhetoric would become less frequent after 1933 due to the increased emphasis on the volksgemeinschaft, it and its ideas would never truly disappear until the overthrow of the regime. The Nazis instead emphasised that the middle-class must become staatsbürger, a publicly active and involved citizen, rather than a selfish, materialistic spießbürger, who was only interested in private life.[229][230]

Sex and gender