The Little Lost Child

| "The Little Lost Child" | |

|---|---|

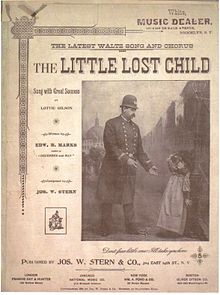

Sheet music cover page | |

| Song | |

| Published | 1894 |

| Genre | Popular music |

| Composer(s) | Joseph W. Stern |

| Lyricist(s) | Edward B. Marks |

"The Little Lost Child" is a popular song of 1894 by Edward B. Marks and Joseph W. Stern, with between one and two million copies in sheet music sales.[2] Also known after its first three words as "A Passing Policeman",[3] it is usually considered to have been the first work promoted as an illustrated song (an early precursor of the music video).[4][5][6][7] The song's success has also been credited to its performance by Lottie Gilson and Della Fox.[8]

Marks was a button salesman who wrote rhymes and verse, and Stern, a necktie salesman who played the piano and wrote tunes. Together they formed a music publishing house called Joseph W. Stern & Co. and became an important part of the Tin Pan Alley sheet music publishing scene.[1][4][5][9] The lyrics, written by Marks and based on a newspaper report,[2] concern a lost little girl found by a policeman, who is then reunited with his estranged wife after it transpires that he is the girl's father. Stern wrote the music for piano and vocals. Joseph W. Stern & Co. "started their career in a little basement at 314 East Fourteenth Street with a 30-cent sign and a $1 letterbox, which to say the least was not large capital even in those days..."[1]

The promoting innovation that made "The Little Lost Child" significant to cultural history was an idea in the mind of George H. Thomas even earlier, in 1892. A production of The Old Homestead at Brooklyn's Amphion Theater, where Thomas was chief electrician, featured the song "Where Is My Wandering Boy Tonight?" illustrated by a single slide of a young man in a saloon. Thomas's idea was to combine a series of images (using a stereopticon) to show a narrative while it was being sung. He approached Stern and Marks about illustrating "The Little Lost Child."[10] With 10 slides on which the lyrics were reproduced, the first performance took place at the Grand Opera House in Manhattan, during the intermission of a Primrose and West minstrel show.[11][12] Initially, the images were displayed upside-down, but once projectionist had corrected this error, the event was an immediate success. The illustrated song technique proved so enduring it was still being used to sell songs before movies and during reel changes in movie theaters as recently as 1937, when some color movies had already begun to appear.[10][11]

"The Little Lost Child" was the first of several hit songs Marks and Stern wrote together as well as the first of several their company published, but it became a true sensation and was well-remembered several decades later.[1] Billboard magazine noted the song's importance in their "honor roll" in 1949.[13]

Lyrics and sheet music

[edit]The song's composition employed a strophic form with a chorus.

[First verse:]

A passing policeman found a little child.

She walked beside him, dried her tears, and smiled.

Said he to her kindly, "Now you must not cry.

I will find your mama for you by and by."

At the station when he asked her for her name

And she answered "Jennie," it made him exclaim:

"At last of your mother, I have now a trace!

Your little features bring back her sweet face."

[Chorus:]

"Do not fear, my little darling, and I will take you right home.

Come and sit down close beside me. No more from me you shall roam.

For you were a babe in arms when your mother left me one day,

Left me at home, deserted, alone, and took you, my child, away."

[Second verse:]

"Twas all through a quarrel, madly jealous she

Vowed then to leave me, woman-like, you see.

Oh, how I loved her, grief near drove me wild!"

"Papa you are crying", lisped the little child

Suddenly the door of the station opened wide,

"Have you seen my darling?" an anxious mother cried.

Husband and wife then meeting face to face;

All is soon forgotten in one fond embrace.[14]

As one writer observed, the sentiment of the song was "[i]n keeping with the sorrowful ballads of the day".[11] An analysis published in 1916 noted that the song was a good example of a narrative with a "swift, dramatic climax", commenting further that "[T]he language and the form would not pass with the humblest editor as poetry, but the essential situation, the dramatic action, and the melody, all taken together, produce the effective result".[15] Sigmund Spaeth wrote in 1926 that "[P]robably Ed Marks was at least pointing his tongue in the general direction of his cheek" when composing the lyrics.[16]

Recordings

[edit]- Jessel, George (1959). George Jessel Sings Tear Jerkers of the Not-so-gay Nineties (LP). Treasure Records. LP 408.

- The Johnson Brothers, "A Passing Policeman", on Various Artists (1991). The Bristol Sessions: Historic Recordings From Bristol, Tennessee (CD). CMF Records. CMF-011-L.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d "Joseph W. Stern & Co. Celebrate 25th Anniversary". The Music Trade Review (PDF). Vol. 68, no. 7. New York: Edward Lyman Bill, Inc. February 15, 1919. p. 48.

- ^ a b Ewen, David (1945). The Life and Death of Tin Pan Alley: The Golden Age of American Popular Music. New York: Funk and Wagnalls. pp. 57–59 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Birthplace of Country Music: Our Musical Heritage:1927 Bristol Sessions". Smithsonian Institution.

- ^ a b Altman, Rick (2007). Silent Film Sound. Columbia University Press. p. 107. ISBN 978-0231116633.

- ^ a b Kohn, Al & Kohn, Bob (2002). Kohn on Music Licensing (Third ed.). Eaglewood Cliffs, NJ: Aspen Publishers. p. 141. ISBN 073551447X.

- ^ Marks, Edward B. & Liebling, A. J. (1934). They All Sang: From Tony Pastor to Rudy Vallee. New York: The Viking Press. p. 32 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Music Video 1900 Style". PBS. 2004. Archived from the original on 2010-01-04.

- ^ Jasen, David A. (2003). Tin Pan Alley encyclopedia of the golden age of American song. Routledge. pp. 270–1/475. ISBN 0-415-93877-5.

- ^ Goldberg, Isaac (1930). Tin Pan Alley: A Chronicle of the American Popular Music Racket. Kessinger Publishing, LLC. pp. 141(376). ISBN 978-1417904532.

- ^ a b Witmark, Isidore & Goldberg, Isaac (1939). From Ragtime to Showtime: The Story of the House of Witmark. New York: Lee Furman, Inc. p. 116.

- ^ a b c Meyer, Hazel (1977). The Gold in Tin Pan Alley. Westport, CN: Greenwood Press. pp. 53–55. ISBN 0837196949.

- ^ Shaw, Arnold (1986). Black Popular Music in America: From the Spirituals, Minstrels, and Ragtime to Soul, Disco, and Hip-hop. New York: Shirmer Books. p. 36. ISBN 0028723104.

- ^ Davis, Gussie (1949). "The Honor Roll of Popular Songwriters No. 24". Billboard. Vol. 61, no. 24. p. 38 – via Google Books.

- ^ Marks, Edward B. & Stern, Joseph W. (1894). The Little Lost Child (Sheet music). New York: Jos. W. Stern & Co.

- ^ Wickes, E. M. (1916). Writing the Popular Song. Springfield, MA: The Home Correspondence School. pp. 70–72 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Spaeth, Sigmund (1979) [1926]. Read 'Em and Weep: The Songs You Forgot To Remember. New York: Da Capo Press. p. 170. ISBN 0306795647.