Garfield Akers

Garfield Akers | |

|---|---|

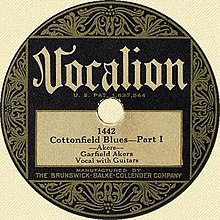

"Cottonfield Blues—Part 1", Vocalion Records label, 1929 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Possibly James Garfield Echols |

| Born | Probably 1908 Mississippi, U.S. |

| Died | c. 1959 Hernando, Mississippi, U.S.[1] |

| Genres | Blues |

| Occupation(s) | Musician |

| Instruments | |

| Years active | 1920s - early 1950s[2] |

Garfield Akers (possibly born James Garfield Echols, probably 1908 – c. 1959)[1] was an American blues singer and guitarist. He had sometimes performed under the pseudonym "Garfield Partee". Information about him is uncertain, and knowledge of his life is based almost entirely on reports of a few contemporary witnesses.

Akers' extant recordings consist of four sides, which are nonetheless historically significant. His most well-known song was his debut single "Cottonfield Blues", a duet with friend and longtime collaborator Joe Callicott on second guitar,[3] based on a song performed by Texas blues musician Henry Thomas a few years earlier.

Biography

[edit]Early life

[edit]Akers came to Hernando, Mississippi, a small town near Memphis, Tennessee, as a young teenager, already playing guitar at the time. In Hernando he met Frank Stokes, who is now often considered the "father of Memphis blues"; together with him he performed as a songster (a form of itinerant musician), comedian and dancer in the Doc Watts and his Spoan's Linament Medicine Show, which toured the southern United States, in the mid to late 1910s. In the mid-1920s, he married Missie (birth name unknown); their marriage remained childless.

Also in the 1920s, he met guitarist Joe Callicott, with whom he played well into his 40s and who was his second guitarist. Both played the Stella brand of guitars, common among blues guitarists at the time, and performed on weekends in the Hernando area, where they made it to local prominence. Akers and Callicott were not professional musicians, however; music was a sideline for them, Akers living as a sharecropper (a form of debt bondage). They rarely played outside the Hernando area; they avoided the Mississippi Delta, the real heartland of Mississippi blues, because it was too dangerous for them there and their local popularity in Hernando ensured better income for less effort.

Recordings

[edit]Callicott appears on Akers' first release for Vocalion Records, the two-part "Cottonfield Blues", which they recorded in September 1929 at the Peabody Hotel in Memphis during a joint recording session with other performers such as Memphis Minnie, Tampa Red, and Kid Bailey. For the recording, Akers was paid 40 dollars,[4] Callicott five.[5] "The Cottonfield Blues" was Akers' trademark tune, which he had practiced continually on his own as well as with Callicott since about 1926/27; the recording accordingly clearly illustrates how well the Akers/Callicott team was attuned to each other. Although Akers had prepared additional material for recording, no further recordings were made by the duo at the Peabody Hotel, as producer J. Mayo Williams was eager to record the other musicians invited to the recording session and thus quickly terminated Akers' recording.

Akers second recording, which took place in February 1930, is of similar character, consisting of "Jumpin and Shoutin' Blues" / "Dough Roller Blues", the latter piece a variation of Hambone Willie Newbern's piece, "Roll and Tumble".[2] Here, due to the close playing of the two, it is hard to say for sure if Callicott was present as a second guitarist. He is not mentioned, but claimed this himself in an interview,.[6] Also, at this session, Callicott recorded his only contemporary release as a soloist, "Travelling Mama Blues", for which Akers is credited as the author.

Later years and death

[edit]In the 1940s, Akers and Callicott ended their musical work together, and Akers moved to Memphis, where he lived as a neighbor of Robert Wilkins and worked in a flour mill.[7] He may have been married to Emma Horton, the mother of Big Walter Horton. With the latter, Nate Armstrong, Little Buddy Doyle, and Robert Lockwood Jr. he often played weekends on Beale Street and performed around Memphis in juke joints. Armstrong also reports that Akers was playing an electric guitar at the time.[4] There are conflicting accounts about the date of his death, most often giving the year 1959, but "The Mississippi Writers and Musicians Project" gives 1958.[8] However, research on death certificates dated between 1955 and 1964 failed. Nate Armstrong reported that he had died as early as 1953 or 1954 after an illness of about six months, but this is not confirmed either.

Only a few years after his death, in 1962, the compilation Really! The Country Blues 1927-1933 included both parts of Akers' "Cottonfield Blues".[9]

Work

[edit]This section possibly contains original research. (May 2023) |

Akers' well-known work includes four tracks recorded by himself and another track recorded by Joe Calicott. All the pieces are played fast and stomping for the time, clearly foreshadowing rhythm and blues as well as rock and roll. Akers had a high-pitched voice, his howling, tremolo style of singing modeled after Ed Newsome. Robert Wilkins reported that the distinctive and, for the time, very unusual rhythm was not necessarily invented by Akers himself, however, but had already been played by two brothers named Byrd in the Hernando area between 1915 and 1920.[5] In the mid-1920s, Akers must have adapted the rhythm, but it is not clear how exactly he came up with it. Similar rhythms do not reappear in the blues until later, with Joe McCoy's "Look Who's Coming Down The Road", recorded in 1935 but not released until 1940, and Robert Wilkins' "Get Away Blues".[10]

The two-part "Cottonfield Blues" is a blues piece for two guitars and vocals in what, from today's perspective, is a very traditional blues scheme. While the rhythm guitar plays in eighth notes, without any special emphasis or a ternary shuffle rather boring, the lead guitar's motif of only four notes, which always starts on the second or fifth eighth note and is downward, creates a counter-rhythm so that the actual heavy times are shifted. This leads to irritation when listening, since the harmony changes do not seem to match the meter changes, especially since the vocals are also rhythmically related to the "correct" meter. This and the bluesy vocal line, which heavily veils the blue notes in intonation and thus distances itself harmonically from the guitars, creates an effect aimed at making the singing, i.e. the singer or narrator, seem left alone, thus heightening the dramaturgy of the textual content (about a man has been abandoned by his lover).

Influence

[edit]Akers' style influenced blues musicians such as John Lee Hooker and Robert Wilkins in his day.[11] Due to his extremely narrow oeuvre, Akers is little known today outside of aficionado circles. "Cottonfield Blues" in particular, however, has been reissued numerous times on vinyl and CD and is now considered a classic of the genre. Bob Dylan biographer Michael Gray hailed the tune as "the birth of rock 'n' roll ... from 1929!",[12] Don Kent pointed out that "only a handful of guitar duets in all blues match the incredible drive, intricate rhythms and ferocious intensity [of the piece]" and called him "one of the greatest vocalists in blues history.".[13] Gayle Dean Wardlow called the record "one of the classic prewar records" with an "amazing rhythm behind Garfield's moanin'."[10] Musicologist Ted Gioia described his style by saying "Here chord fragments ricochet like bullets off the fretboard, serving as bits of harmonic shrapnel underscoring Akers piercing vocal attack, a long lingering wail that contrasts pleasingly with the rapidfire pulsations of his guitar.".[14]

Discography

[edit]All of the pieces have been reissued numerous times on compilations since their original publication; these are not listed here.

- "Cottonfield Blues, Part 1" / "Cottonfield Blues, Part 2", (1929), (Vocalion Records 1442)

- "Jumpin And Shoutin' Blues" / "Dough Roller Blues", (1930), (Vocalion Records 1481)

References

[edit]- ^ a b Eagle, Bob; LeBlanc, Eric S. (2013). Blues - A Regional Experience. ABC-CLIO. p. 219. ISBN 978-0313344237.

- ^ a b "Garfield Akers Biography, Songs, & Albums". AllMusic. Retrieved 2022-05-03.

- ^ Palmer, Robert (1982). Deep blues. Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England. ISBN 0-14-006223-8. OCLC 8168726.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Jim O'Neal, Garfield Akers – … to Beale Street and the Juke Joints , p. 28

- ^ a b Gayle Dean Wardlow: Garfield Akers – From the Hernando Cottonfields … , p. 27

- ^ Gayle Dean Wardlow: Garfield Akers – From the Hernando Cottonfields … , p. 26

- ^ Reichert, Carl-Ludwig (2001). Blues: Geschichte und Geschichten (Orig.-ausg ed.). München: Dt.-Taschenbuch-Verl. ISBN 3-423-24259-0. OCLC 248338615.

- ^ "Mississippi musicians play the blues, rock n' roll, gospel, jazz, classical, rock, rockbilly and more". 2006-08-11. Archived from the original on 11 August 2006. Retrieved 2022-05-04.

- ^ "untitled". 2006-11-06. Archived from the original on 6 November 2006. Retrieved 2022-05-04.

- ^ a b Wardlow, Gayle (1998). Chasin' that devil music: searching for the blues. Edward M. Komara. San Francisco, Calif.: Miller Freeman Books. ISBN 0-87930-652-1. OCLC 48138836.

- ^ Robert Santelli: The Big Book Of Blues. p. 5

- ^ Gray, Michael (2000). Song & dance man III: the art of Bob Dylan. Michael Gray. London: Continuum. ISBN 0-304-70762-7. OCLC 42049290.

- ^ Don Kent. In: The Best There Ever Was . CD booklet, Yazoo Records, YA 3002, 2003

- ^ Gioia, Ted (2008). Delta blues: the life and times of the Mississippi Masters who revolutionized American music. New York: W.W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-06258-8. OCLC 212893669.

Bibliography

[edit]- Robert Santelli, The Big Book Of Blues – A Biographical Encyclopedia, 1993, ISBN 0-14-015939-8, p. 5