Anarchism in Spain

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (March 2020) |

| Part of a series on |

| Anarchism |

|---|

|

Anarchism in Spain has historically gained some support and influence, especially before Francisco Franco's victory in the Spanish Civil War of 1936–1939, when it played an active political role and is considered the end of the golden age of classical anarchism.

There were several variants of anarchism in Spain, namely expropriative anarchism in the period leading up to the conflict, the peasant anarchism in the countryside of Andalusia; urban anarcho-syndicalism in Catalonia, particularly its capital Barcelona; and what is sometimes called "pure" anarchism in other cities such as Zaragoza. However, these were complementary trajectories and had many ideological similarities. Early on, the success of the anarchist movement was sporadic. Anarchists would organize a strike and ranks would swell. Usually, repression by police reduced the numbers again, but at the same time further radicalized many strikers. This cycle helped lead to an era of mutual violence at the beginning of the 20th century in which armed anarchists and pistoleros, armed men paid by company owners, were both responsible for political assassinations.

In the 20th century, this violence began to fade, and the movement gained speed with the rise of anarcho-syndicalism and the creation of the huge libertarian trade union, the Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (CNT). General strikes became common, and large portions of the Spanish working class adopted anarchist ideas. There also emerged a small individualist anarchist movement based on publications such as Iniciales and La Revista Blanca.[1] The Federación Anarquista Ibérica (FAI) was created as a purely anarchist association, with the intention of keeping the CNT focused on the principles of anarchism.

Anarchists played a central role in the fight against Francisco Franco during the Spanish Civil War. At the same time, a far-reaching social revolution spread throughout Spain, where land and factories were collectivized and controlled by the workers. All remaining social reforms ended in 1939 with the victory of Franco, who had thousands of anarchists executed. Resistance to his rule never entirely died, with resilient militants participating in acts of sabotage and other direct action after the war, and making several attempts on the ruler's life. Their legacy remains important to this day, particularly to anarchists who look at their achievements as a historical precedent of anarchism's validity.

History[edit]

Beginning[edit]

In the mid-19th century, revolutionary ideas were generally unknown in Spain. There was a history of peasant unrest in some parts of the country, but this was not related to any political movement, rather it was borne out of circumstances. The same was true in the cities; long before workers were familiar with anarcho-syndicalism, there were general strikes and other conflicts between workers and their employers.

The closest thing to a radical movement was found amongst the followers of the ideas laid out by the French anarchist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon. Mutualism had a considerable influence on the Spanish cooperativist movement, which advocated for a peaceful and gradualist approach to defeating capitalism, as well as the federalist movement, which envisioned a society of local municipalities joining together and coordinating without any need for a centralized government.[2] The most influential proponent of mutualism in Spain was the federal republican Francesc Pi i Margall (named, upon his death, "the wisest of the federalists, almost an anarchist" by anarchist thinker Ricardo Mella), who in his book Reacción y Revolución wrote that "every man who has power over another is a tyrant" and called for the "division and subdivision of power".[3] Another disciple of Proudhon was Ramón de la Sagra, who founded the world's first anarchist journal El Porvenir, which was published for a brief time in Galicia.[4] Mutualism subsequently gained widespread popularity throughout Spain, becoming the dominant tendency within the Spanish federal republican movement by the 1860s.[3] It was around this time that the revolutionary socialist ideas of Mikhail Bakunin, based in collectivism, a focus on direct action and a militant anti-clericalism, also began to rise to prominence in Spain.[5]

The earliest successful attempt to introduce anarchism to the Spanish masses was undertaken by a middle-aged Italian revolutionary named Giuseppe Fanelli.[6] An early partisan of the Young Italy movement, during the Italian Revolution Fanelli had given up his career to participate in the Risorgimento under the command of Giuseppe Garibaldi and Giuseppe Mazzini. After the proclamation of the unified Kingdom of Italy in 1861, Fanelli was elected to the Italian Parliament as part of Mazzini's far-left coalition, before meeting Bakunin and becoming an anarchist.[7]

Following the Glorious Revolution and the beginning of the Sexenio Democrático in 1868, the new Provisional Government declared the right to freedom of association, allowing Spanish workers' societies to begin re-emerging from the secrecy that they had previously lived under.[8] Bakunin took this as an opportunity to sponsor Fanelli on a journey to Spain in order to recruit members for the International Workingmen's Association (IWA),[6] an international organization that aimed to unify groups working for the benefit of the working class. Arriving in Barcelona on a shoestring budget, Fanelli met with and borrowed money from Élie Reclus, in order to finance his trip to Madrid, where he met with the owner of the federal republican newspaper La Igualdad and was put in touch with a group of radical workers.[9]

Fanelli spoke in French and Italian, so those present could only understand bits of what he was saying, except for one man, Tomás González Morago, who knew French. Nevertheless, Fanelli was able to convey his libertarian and anti-capitalist ideas to the audience. Anselmo Lorenzo gave an account of his oratory: "His voice had a metallic tone and was susceptible to all the inflexions appropriate to what he was saying, passing rapidly from accents of anger and menace against tyrants and exploiters to take on those of suffering, regret and consolation...we could understand his expressive mimicry and follow his speech."[10] These workers, longing for something more than the mild radicalism of the day, became the core of the Spanish Anarchist movement, quickly spreading "the Idea" across Spain. The oppressed and marginalized working classes were very susceptible to an ideology attacking institutions they perceived to be oppressive, namely the state, capitalism and organized religion.

As a result, all the workers that were present at the meeting declared themselves in support of the International and Fanelli subsequently extended his stay in the city, holding "propaganda sessions" with the nascent anarchist adherents - paying particular attention to Anselmo Lorenzo. On January 24, 1869, Fanelli held his last meeting with the anarchist workers of Madrid, in which they declared the establishment of the Madrid section of the IWA.[10] Fanelli explained his decision to leave Spain was so that the anarchists there could develop themselves and their groups "by their own efforts, with their own values," in order to maintain spontaneity, plurality and individuality within the workers' movement.[11] The anarchists of the Madrid section subsequently began to spread their ideas by holding meetings, giving speeches, and publishing their newspaper La Solidaridad. By 1870, the Madrid chapter of the International had gained roughly 2,000 members.[12]

Fanelli then returned to Barcelona where he held another meeting, attracting a number of more radical students such as Rafael Farga i Pellicer to the idea of anarchism,[7] which subsequently gained a much larger following in Barcelona, already a bastion of proletarian rebellion, Luddism, and trade unionism.[13] In May 1869, Farga i Pellicer spearheaded the establishment of the Barcelona section of the IWA, which began to advocate for socialism within the structures that had already been set up by the 1868 Barcelona Workers' Congress. The IWA's influence was thereby extended to a number of workers' societies and the federal republican newspaper La Federación, quickly bringing thousands of workers under the anarchist banner.[14] Farga i Pellicer even went on to participate in the International's Basel Congress as a delegate for the Spanish sections, where he joined Bakunin's "International Alliance of Socialist Democracy".[15]

Anarchism had soon taken root throughout Spain, in villages and in cities, and in scores of autonomous organizations.[15] Many of the rural pueblos were already anarchic in structure prior to the spread of "anarchist" ideas.[16] In February 1870, the Madrid section of the IWA published in La Solidaridad a call for all Spanish sections to convene a national workers' congress, which was eventually decided would be held in Barcelona.[17]

On June 18, 1870, the First Spanish Workers' Congress convened at the Teatro Circo Barcelonés, where delegates from 150 workers' associations met, along with thousands of common workers observing ("occupying every seat, filling the hallways, and spilling out beyond the entrance".[18] The agenda was closely guided by the anarchists around Rafael Farga i Pellicer, who opened the congress with a declaration against the state and proposed an distinctly anarchist program for the Spanish Regional Federation of the IWA (Spanish: Federación Regional Española de la Asociación Internacional de Trabajadores, FRE-AIT).[19] Despite the clear dominance of anarchism within the Congress, there also existed three other main tendencies: the "associatarians" that were interested in the cultivation of cooperatives, the "politicians" that wanted to mobilize workers to participate in elections, and the "pure-and-simple" trade unionists that were focused on immediate workplace struggles.[20] There was a particularly sharp conflict between the anarchists, who advocated for abstentionism and direct action, and the "politicians", during which congress took a line of compromise regarding electoralism: allowing individual members to participate in elections if they wished, but also committing itself officially to abstentionism and anti-statism.[21] Congress also adopted a "dual structure" for the FRE-AIT whereby workers would be organized into both trade unions based on their profession and local federations based on their location, which could then federate together from the bottom-up, laying an anti-bureaucratic and decentralist foundation for syndicalism in Spain.[22]

Socialists and liberals within the Spanish Federation sought to reorganize Spain in 1871 into five trade sections with various committees and councils. Many anarchists within the group felt that this was contrary to their belief in decentralization. A year of conflict ensued, in which the anarchists fought the "Authoritarians" within the Federation and eventually expelled them in 1872. In the same year, Mikhail Bakunin was expelled from the International by the Marxists, who were the majority. Anarchists, seeing the hostility from previous allies on the Left, reshaped the nature of their movement in Spain. The Spanish Federation became decentralized, now dependent on action from rank-and-file workers rather than bureaucratic councils; that is, a group structured according to anarchist principles.

Early turmoil of 1873–1900[edit]

In the region of Alcoy, workers struck in 1873 for the eight-hour day following much agitation from the anarchists. The conflict turned to violence when police fired on an unarmed crowd, which caused workers to storm City Hall in response. Dozens were dead on each side when the violence ended. Sensational stories were made up by the press about atrocities that never took place: priests crucified, men doused in gasoline and set on fire, etc.[23] The events became known as the Petroleum Revolution.

This was followed by the Cantonal rebellion, during which several independent cantons rose against the First Spanish Republic. Anarchism had a considerable influence in this series of insurrections especially in the Canton of Cartagena, which was the only canton to last more than a few days.[24][25]

The government quickly moved to suppress the Spanish Federation. Meeting halls were shut down, members jailed, and publications banned. Until around the start of the 20th century, proletarian anarchism remained relatively fallow in Spain.

However, anarchist ideas remained popular in the rural countryside, where destitute peasants waged a lengthy series of unsuccessful rebellions in attempts to create anarchist communism. Throughout the 1870s, the Spanish Federation drew most of its members from the peasant areas of Andalusia after the decline of its urban following. In the early 1870s, a section of the International was formed in Córdoba, forming a necessary link between the urban and rural movements.

These small gains were largely destroyed by State repression, which by the mid-1870s had forced the entire movement underground. The Spanish Federation faded away, and conventional trade unionism for a while began to replace revolutionary action, although anarchists remained abundant and their ideas not forgotten; the liberal nature of this period was perhaps borne out of despair rather than disagreement with revolutionary ideas. Anarchists were left to act as tigres solitarios (roughly "lone tigers"); attempts at mass organization, as in the Pact of Union and Solidarity, had some ephemeral success but were destined to failure.

Six people died in June 1896 when a bomb was thrown at the Barcelona Corpus Christi procession. Police attributed the act to anarchists who met with the severest repression. As many as 400 people were brought to the dungeons of Montjuïc Castle in Barcelona. International outrage followed reports that the prisoners were brutally tortured: men hanged from ceilings, genitals twisted and burned, fingernails ripped out. Several died before being brought to trial, and five were eventually executed. In 1897, the Italian anarchist Michele Angiolillo assassinated the Prime Minister of Spain, Antonio Cánovas del Castillo, in part as retaliation for the repression in Barcelona.

The anarchist idea was propagated by many periodicals like El Socialismo started by Fermín Salvochea. Salvochea is considered one of the earliest pioneers in the propagation and organization along anarchist lines.[26]

Rise of the CNT[edit]

The anarchist movement lacked a stable national organization in its early years. Anarchist Juan Gómez Casas discusses the evolution of anarchist organization before the creation of the CNT: "After a period of dispersion, the Federation of Workers of the Spanish Region disappeared, to be replaced by the Anarchist Organization of the Spanish Region.... This organization then changed, in 1890, into the Solidarity and Assistance Pact, which was itself dissolved in 1896 because of repressive legislation against anarchism and broke into many nuclei and autonomous workers' societies.... The scattered remains of the FRE gave rise to Solidaridad Obrera in 1907, the immediate antecedent of the [CNT]."[27]

There was a consensus amongst anarchists in the early 20th century that a new, national labor organization was needed to bring coherency and strength to their movement. This organization, named the Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (CNT) was formed in October 1910 during a congress of Solidaridad Obrera. During this congress, a resolution was passed declaring that the purpose of the CNT would be to "hasten the integral economic emancipation of the entire working class through the revolutionary expropriation of the bourgeoisie...." The CNT started off fairly small, with about 30,000 members across various unions and confederations.

The national confederation was split into smaller regional ones, which were again broken down into smaller trade unions. Despite this many-tiered structure, bureaucracy was consciously avoided. Initiatives for decisions came largely from the individual unions. There were no paid officials; all positions were staffed by common workers. Decisions made by the national delegations did not have to be followed. The CNT was in these respects quite different from the comparatively rigid socialist unions.

A general strike was called a mere five days after its founding by triumphant, and perhaps overzealous, workers. It spread across several cities throughout Spain; in one city, workers took over the community and killed the mayor. Troops moved into all major cities and the strike was quickly crushed. The CNT was declared an illegal organization, and thus went underground only a week after its founding. A few years later it continued with overt strike actions, as in the general strike organized in tandem with the Socialist-dominated UGT (a rare occurrence, as the two groups were usually at odds) to protest the rising cost of living.

CNT following World War I[edit]

Spain's economy suffered upon the decline of the wartime economy. Factories closed, unemployment soared and wages declined. Expecting class conflict, especially in light of the then recent Russian Revolution, much of the capitalist class began a bitter war against unions, particularly the CNT. Lockouts became more frequent. Known militants were blacklisted. Pistoleros, or assassins, were hired to kill union leaders. Scores, perhaps hundreds, of anarchists were murdered during this time period. Anarchists responded in turn with a number of assassinations, the most famous of which is the murder of Prime Minister Eduardo Dato Iradier.

The CNT, by this time, had as many as a million members. It retained its focus on direct action and syndicalism; this meant that revolutionary currents in Spain were no longer on the fringe, but very much in the mainstream. While it would be false to say that the CNT was entirely anarchist, the prevailing sentiment undoubtedly leaned in that direction. Every member elected to the "National Committee" was an overt anarchist. Most rank and file members espoused anarchist ideas. Indeed, much of Spain seemed to be radiant with revolutionary fervor; along with waves of general strikes (as well as mostly successful strikes with specific demands), it was not uncommon to see anarchist literature floating around ordinary places or common workers discussing revolutionary ideas. One powerful opponent from the upper classes (Diaz del Moral) claims that "the total working population" was overcome with the spirit of revolt, that "all were agitators."

Whereas anarchism in Spain was previously disjointed and ephemeral, even the smallest of towns now had organizations and took part in the movement. Different parts of the CNT (unions, regions, etc.) were autonomous and yet inextricably linked. A strike by workers in one field would often lead to solidarity strikes by workers in an entire city. This way, general strikes often were not "called", they simply happened organically.

General strike of 1919[edit]

In 1919, employers at a Barcelona hydroelectric plant, known locally as La Canadiense, cut wages, triggering a 44-day-long and hugely successful general strike with over 100,000 participants. Employers immediately attempted to respond militantly, but the strike had spread much too rapidly. Employees at another plant staged a sit-in supporting their fellow workers. About a week later, all textile employees walked out. Soon after, almost all electrical workers went on strike as well.

Barcelona was placed under martial law, yet the strike continued in full force. The union of newspaper printers warned the newspaper owners in Barcelona that they would not print anything critical of the strikers. The Government in Madrid tried to destroy the strike by calling up all workers for military service, but this call was not heeded, as it was not even printed in the paper. When the call got to Barcelona by word of mouth, the response was yet another strike by all railway and trolley workers.

The Government in Barcelona finally managed to settle the strike, which had effectively crippled the Catalan economy. All of the striking workers demanded an eight-hour day, union recognition, and the rehiring of fired workers. All demands were granted. It was also demanded that all political prisoners be released. The government agreed, but refused to release those currently on trial. Workers responded with shouts of "Free everybody!" and warned that the strike would continue in three days if this demand was not met. Sure enough, this is what occurred. However, members of the Strike Committee and many others were immediately arrested and police effectively stopped the second strike from reaching great proportions.

The Government tried to appease the workers, who were clearly on the verge of insurrection. Tens of thousands of unemployed workers were returned to their jobs. The eight-hour day was declared for all workers. Thus, Spain became the first country in the world to pass a national eight-hour day law, as a result of 1919's general strike.

After the 1919 general strike, increasing violence against CNT organizers, combined with the rise of the Primo de Rivera dictatorship (which banned all anarchist organizations and publications), created a lull in anarchist activity. Many anarchists responded to police violence by becoming pistoleros themselves. This was a period of mutual violence, in which anarchist groups including Los Solidarios assassinated political opponents. Many anarchists were killed by gunmen of the other side.

FAI[edit]

During the Primo de Rivera years, much of the CNT leadership began to espouse a "moderate" revolutionary syndicalism, ostensibly holding an anarchist outlook but holding that the fulfilment of anarchist hopes would not come immediately, and insisting on the need for a more disciplined and organised trade-union movement in order to work towards libertarian communism. The Federación Anarquista Ibérica (FAI) was formed in 1927 to combat this tendency.

Its organization was based on autonomous affinity groups. The FAI remained a very secretive organization, even after acknowledging its existence two years after its formation. Its surreptitious nature makes it difficult to judge the extent of its membership. Estimates of FAI membership at the time immediately preceding the revolution range from 5,000 to 30,000. Membership dramatically increased during the first few months of the Civil War.

The FAI was not ideally libertarian, being dominated by very aggressive militants such as Juan García Oliver and Buenaventura Durruti. However, it was not authoritarian in its actual methods; it allowed freedom of dissent to its members. In fact the overall organization of the FAI was very loose, unlike Bakunin's "Alliance" which was, however, an important precedent in creating an organization for pushing forward anarchist ideology.

The FAI was militantly revolutionary, with actions including bank robberies to acquire funds, and the organization of general strikes, but at times became more opportunist. It supported moderate efforts against the Rivera dictatorship, and in 1936, contributed to establishment of the Popular Front. By the time the anarchist organizations began cooperating with the Republican government, the FAI essentially became a de facto political party and the affinity group model was dropped, not uncontroversially.

Fall of Rivera and the Second Republic[edit]

The CNT initially welcomed the Republic as a preferable alternative to dictatorship, while still holding on to the principle that all states are inherently deleterious, if perhaps to varying degrees of severity.

This relationship did not last long, though. A strike by telephone workers led to street fighting between CNT and government forces; the army used machine guns against the workers. A similar strike broke out a few weeks later in Seville; twenty anarchists were killed and one hundred were wounded after the army besieged a CNT meeting place and destroyed it with artillery. An insurrection occurred in Alt Llobregat, where miners took over the town and raised red and black flags in town halls. These actions provoked harsh government repression and achieved little tangible success. Some of the most active anarchists, including Buenaventura Durruti and Francisco Ascaso, were deported to Spanish territory in Africa. This provoked protest and an insurrection in Terrassa, where, like in Alto Llobregat, workers stormed town halls and raised their flags. Another failed insurrection took place in 1933, when anarchist groups attacked military barracks with the hope that those inside would support them. The government had already learned of these plans, however, and quickly suppressed the revolt.

None of these actions had any success. They resulted in thousands of jailed anarchists and a wounded movement. At the same time, infighting between the syndicalist Treintismo and the insurrectionalist FAI hurt the unity of the anarchist struggle.

Prelude to revolution[edit]

The national focus on Republic and reform led the anarchists to cry "Before the ballot boxes, social revolution!" In their view, liberal electoral reforms were futile and undesirable, and impeded the total liberation of the working classes.

An uprising took place in December 1933. Aside from a prison break in Barcelona, no gains were made by revolutionaries before the police quelled the revolt in Catalonia and most of the rest of the country. Zaragoza saw ephemeral insurrection in the form of street fighting and the occupation of certain buildings.[28]

An important strike took place in April, again in Zaragoza. It lasted five weeks, shutting down most of Zaragoza's economy. Other parts of the country were supportive; anarchists in Barcelona took care of the strikers' children (about 13,000 of them)[29] while the CNT federation of Logroño had offered to take care of as many as 5,000.[30]

Asturias[edit]

The Asturian miners' strike of 1934 began with attacks on barracks of the Civil Guard. In the town of Mieres, police barracks and the town hall were taken over. Strikers moved on, continuing to occupy towns, even the capital of Asturias in Oviedo. Workers had control over most of Asturias, under chants of "Unity, Proletarian brothers!" The ports of Gijón and Avilés remained open. Anarchist militants defending against the imminent arrival of government troops were denied sufficient arms by suspicious communists. So fell the uprising, with great violence upon the rebels, but also with great unity and revolutionary fervor amongst the working classes.

The crushing of the revolt was led by General Francisco Franco, who would later lead a rebellion against the republic and become dictator of Spain. The use of the Foreign Legion and the Moorish Regulares to kill Spaniards caused public outrage. Captured miners faced torture, rape, mutilation, and execution. This foreshadowed the same brutality seen two years later in the Spanish Civil War.

Popular Front[edit]

With the growth of right-wing political parties (Gil Robles' conservative Spanish Confederation of the Autonomous Right, for example), leftist parties felt the need to join together in a "Popular Front." This included Republicans, Socialists, Communists, and other left parties; Anarchists were not willing to support it but refused to attack it, either, thus helping it get into power.

The more radical elements of the CNT-FAI were not satisfied with electoral politics. In the months after the Popular Front's rise to power, strikes, demonstrations, and rebellions broke out throughout Spain. Throughout the countryside, almost 5 km2 of land were taken over by squatters. The Popular Front parties began to lose control. Anarchists would continue to strike even when prudent socialists called it off, taking food from stores when strike funds ran out.

The CNT's national congress in May 1936 had an overtly revolutionary tone. Among the topics discussed were sexual freedom, plans for agrarian communes, and the elimination of social hierarchy.

Individualist anarchism[edit]

Spanish individualist anarchism was influenced by American individualist anarchism but it was mainly connected to the French currents. At the start of the 20th century people such as Dorado Montero, Ricardo Mella, Federico Urales, Mariano Gallardo and J. Elizalde translated French and American individualists. Important in this respect were also magazines such as La Idea Libre, La Revista Blanca, Etica, Iniciales, Al margen, Estudios, and Nosotros. The most influential thinkers there were Max Stirner, Émile Armand and Han Ryner. Just as in France, Esperanto, anationalism, anarcho-naturism and free love were present as philosophies and practices within Spanish individualist anarchist circles. Later Armand and Ryner started publishing in the Spanish individualist press. Armand's concept of amorous camaraderie had an important role in motivating polyamory as realization of the individual.[31]

Historian Xavier Diez wrote on the subject in El anarquismo individualista en España: 1923-1938.[1] Utopia sexual a la prensa anarquista de Catalunya. La revista Ética-Iniciales (1927–1937) deals with free love thought in Iniciales.[32] Diez reports that the Spanish individualist anarchist press was widely read by members of anarcho-communist groups and by members of the anarcho-syndicalist trade union CNT. There were also the cases of prominent individualist anarchists such as Federico Urales and Miguel Giménez Igualada who were members of the CNT and J. Elizalde who was a founding member and first secretary of the Iberian Anarchist Federation.[1]

An important Spanish individualist anarchist was Miguel Giménez Igualada who wrote the lengthy theory book called Anarchism espousing his individualist anarchism.[33] Between October 1937 and February 1938 he started as editor of the individualist anarchist magazine Nosotros,[31] in which many works of Han Ryner and Émile Armand appeared, and also participated in the publishing of another individualist anarchist magazine Al Margen: Publicación quincenal individualista.[34] In his youth he engaged in illegalist activities.[1] Igualada's thought was deeply influenced by Stirner, of which he was the main popularizer in Spain through his writings. He published and wrote the preface[31] to the fourth edition in Spanish of The Ego and Its Own from 1900. He proposed the creation of a Union of Egoists, a Federation of Individualist Anarchists in Spain, but did not succeed.[35] In 1956, Igualada published an extensive treatise on Stirner, which he dedicated to fellow individualist anarchist Émile Armand.[36] Afterwards, he travelled and lived in Argentina, Uruguay and Mexico.[1]

Anarcho-naturism[edit]

Anarcho-naturism was quite important at the end of the 1920s in the Spanish anarchist movement[37] In France, later important propagandists of anarcho-naturism include Henri Zisly[38] and Émile Gravelle who collaborated in La Nouvelle Humanité, Le Naturien, Le Sauvage, L'Ordre Naturel, and La Vie Naturelle.[39] Their ideas were important in individualist anarchist circles in France as well as Spain, where Federico Urales (pseudonym of Joan Montseny) promoted the ideas of Gravelle and Zisly in La Revista Blanca (1898–1905).[40]

The linking role played by the Sol y Vida group was very important. The goal of this group was to take trips and enjoy the open air. The Naturist athenaeum, Ecléctico, in Barcelona, was the base from which the activities of the group were launched. First Etica and then Iniciales, which began in 1929, were the publications of the group, which lasted until the Spanish Civil War. We must be aware that the naturist ideas expressed in them matched the desires that the libertarian youth had of breaking up with the conventions of the bourgeoisie of the time. That is what a young worker explained in a letter to Iniciales. He writes it under the odd pseudonym of silvestre del campo (wild man in the country). "I find great pleasure in being naked in the woods, bathed in light and air, two natural elements we cannot do without. By shunning the humble garment of an exploited person, (garments which, in my opinion, are the result of all the laws devised to make our lives bitter), we feel there no others left but just the natural laws. Clothes mean slavery for some and tyranny for others. Only the naked man who rebels against all norms, stands for anarchism, devoid of the prejudices of outfit imposed by our money-oriented society."[37]

Isaac Puente, an influential Spanish anarchist during the 1920s and 1930s and an important propagandist of anarcho-naturism,[41][42] was a militant of both the CNT anarcho-syndicalist trade union and Iberian Anarchist Federation. He published the book El Comunismo Libertario y otras proclamas insurreccionales y naturistas (en:Libertarian Communism and other insurrectionary and naturist proclaims) in 1933, which sold around 100,000 copies,[43] and wrote the final document for the Extraordinary Confederal Congress of Zaragoza of 1936 which established the main political line for the CNT for that year.[44] Puente was a doctor who approached his medical practice from a naturist point of view.[41] He saw naturism as an integral solution for the working classes, alongside Neo-Malthusianism, and believed it concerned the living being while anarchism addressed the social being.[45] He believed capitalist societies endangered the well-being of humans from both a socioeconomic and sanitary viewpoint, and promoted anarcho-communism alongside naturism as a solution.[41]

The "relation between Anarchism and Naturism gives way to the Naturist Federation, in July 1928, and to the lV Spanish Naturist Congress, in September 1929, both supported by the Libertarian Movement. However, in the short term, the Naturist and Libertarian movements grew apart in their conceptions of everyday life. The Naturist movement felt closer to the Libertarian individualism of some French theoreticians such as Henri Ner (real name of Han Ryner) than to the revolutionary goals proposed by some Anarchist organisations such as the FAI, (Federación Anarquista Ibérica)".[37] This ecological tendency in Spanish anarchism was strong enough as to call the attention of the CNT–FAI in Spain. Daniel Guérin in Anarchism: From Theory to Practice reports:

Spanish anarcho-syndicalism had long been concerned to safeguard the autonomy of what it called "affinity groups." There were many adepts of naturism and vegetarianism among its members, especially among the poor peasants of the south. Both these ways of living were considered suitable for the transformation of the human being in preparation for a libertarian society. At the Saragossa congress the members did not forget to consider the fate of groups of naturists and nudists, "unsuited to industrialization." As these groups would be unable to supply all their own needs, the congress anticipated that their delegates to the meetings of the confederation of communes would be able to negotiate special economic agreements with the other agricultural and industrial communes. On the eve of a vast, bloody, social transformation, the CNT did not think it foolish to try to meet the infinitely varied aspirations of individual human beings.[46]

Anarchist presence in the Spanish Civil War[edit]

The Republican government responded to the threat of a military uprising with remarkable timidity and inaction. The CNT had warned Madrid of a rising based in Morocco months earlier and even gave the exact date and time of 5 am on July 19, which it had learned through its impressive espionage apparatus. Yet, the Popular Front did nothing, and refused to give arms to the CNT. Tired of begging for weapons and being denied, CNT militants raided an arsenal and doled out arms to the unions. Militias were placed on alert days before the planned rising.

The rising was actually moved forward two days to July 17, and was crushed in areas heavily defended by anarchist militants, such as Barcelona. Some anarchist strongholds, such as Zaragoza, fell, to the great dismay of those in Catalonia; this is possibly due to the fact that they were being told that there was no "desperate situation" by Madrid and thus did not prepare. The Government still remained in a state of denial, even saying that the "Nationalist" forces had been crushed in places where it had not been. It is largely because of the militancy on the part of the unions, both anarchist and communist, that the Rebel forces did not win the war immediately.

Anarchist militias were remarkably libertarian within themselves, particularly in the early part of the war before being partially absorbed into the regular army. They had no rank system, no hierarchy, no salutes, and those called "Commanders" were elected by the troops.

The most effective anarchist unit was the Durruti Column, led by militant Buenaventura Durruti. It was the only anarchist unit which managed to gain respect from otherwise fiercely hostile political opponents. In a section of her memoirs which otherwise lambastes the anarchists, Dolores Ibárruri states: "The war developed with minimal participation from the anarchists in its fundamental operations. One exception was Durruti..." (Memorias de Dolores Ibarruri, p. 382). The column began with 3,000 troops, but at its peak was made up of about 8,000 men. They had a difficult time getting arms from a fearful Republican government, so Durruti and his men compensated by seizing unused arms from government stockpiles. Durruti's death on November 20, 1936, weakened the Column in spirit and tactical ability; they were eventually incorporated, by decree, into the regular army. Over a quarter of the population of Barcelona attended Durruti's funeral. It is still uncertain how Durruti died; modern historians tend to agree that it was an accident, perhaps a malfunction with his own gun or a result of friendly fire, but widespread rumors at the time claimed treachery by his men; anarchists tended to claim that he died heroically and was shot by a fascist sniper. Given the widespread repression against Anarchists by the Soviets, which included torture and summary executions, it is also possible that it was a USSR plot.[47]

Another famous unit was the Iron Column, made up of ex-convicts and other "disinherited" Spaniards sympathetic to the Revolution. The Republican government denounced them as "uncontrollables" and "bandits", but they had a fair amount of success in battle. In March 1937 they were incorporated into the regular army.

CNT–FAI collaboration with government during the war[edit]

In 1936, the CNT decided, after several refusals, to collaborate with the government of Largo Caballero. Juan García Oliver became Minister of Justice (where he abolished legal fees and had all criminal dossiers destroyed), Diego Abad de Santillán became Minister of the Economy, and Federica Montseny became Minister of Health, to name a few instances.

During the Spanish Civil War, many anarchists outside of Spain criticized the CNT leadership for entering into government and compromising with communist elements on the Republican side. Those in Spain felt that this was a temporary adjustment, and that once Franco was defeated, they would continue in their libertarian ways. There was also concern with the growing power of authoritarian communists within the government. Montseny later explained: "At that time we only saw the reality of the situation created for us: the communists in the government and ourselves outside, the manifold possibilities, and all our achievements endangered."[48]

Some anarchists outside of Spain viewed their concessions as necessary considering the grim possibility of losing everything should the fascists win the war. Emma Goldman said: "With Franco at the gate of Madrid, I could hardly blame the CNT–FAI for choosing a lesser evil: participation in government rather than dictatorship, the most deadly evil."[49]

Spanish Revolution of 1936[edit]

Along with the fight against fascism, there was a profound anarchist revolution throughout Spain. Much of Spain's economy was put under worker control. In anarchist strongholds such as Catalonia, the figure was as high as 75%, but lower in areas with heavy socialist influence. Factories were run through worker committees; agrarian areas became collectivized and run as libertarian communes. Even places like hotels, barber shops, and restaurants were collectivized and managed by their workers.

The anarchist held areas were run according to the basic principle of "From each according to his ability, to each according to his need." In some places, money was entirely eliminated, to be replaced with vouchers. Numerous sources attest that industrial productivity doubled almost everywhere across the country and agricultural yields being "30–50%" larger, demonstrated by Emma Goldman, Augustin Souchy, Chris Ealham, Eddie Conlon, Daniel Guerin and others. Of the resulting industrial output, Republican military commander Vicente Rojo Lluch said "Notwithstanding lavish expenditures of money on this need, our industrial organization was not able to finish a single kind of rifle or machine gun or cannon."[50]

Anarchic communes often produced more than before the collectivization. Yields were increased by as much as 50% as a result of newly applied scientific methods. However, critics often dispute these claims. Currency remained in use as a 'family wage' in some areas, while in other areas the use of currency was abolished. The newly liberated zones worked on entirely socialist libertarian principles; decisions were made through councils of ordinary citizens without any sort of bureaucracy. (The CNT-FAI leadership was at this time not nearly as radical as the rank-and-file members responsible for these sweeping changes.)[51]

Franco years[edit]

When Francisco Franco took power in 1939, he had tens of thousands of political dissidents executed. The total number of politically motivated killings between 1939 and 1943 is estimated to be around 200,000.[52] Forced labor camps were opened up, where, according to historian Antony Beevor, "the system was probably as bad as in Germany or Russia." Despite these actions, underground resistance to Franco's rule lingered for decades. Actions by the Resistance included, among other things, sabotage, releasing prisoners, underground organizing of workers, aiding fugitives and refugees, and assassinations of government officials.

Little attention was paid to the Spaniards who refused to accept Franco's rule, even by those who had been against him during the war. Miguel García García, an anarchist jailed for twenty-two years, describes their circumstances in his 1972 book: "When we lost the war, those who fought on became the Resistance. But to the world, the Resistance had become criminals, for Franco made the laws, even if, when dealing with political opponents, he chose to break the laws established by the constitution; and the world still regards us as criminals. When we are imprisoned, liberals are not interested, for we are 'terrorists'".

The guerilla resistance (referred to in Spain as Maquis) was effectively ended around 1960 with the death of many of its more experienced militants. In the period from the end of the war until 1960, according to government sources, there were 1,866 clashes with security forces and 535 acts of sabotage. 2,173 guerillas were killed and 420 were wounded, while the figures for government forces lost amount to only 307 killed and 372 wounded. 19,340 resistance fighters were arrested over this time interval. Those who aided the guerillas were met with similar brutality; as many as 20,000 were arrested over the years on this charge, with many facing torture during interrogation.

The Spanish government under Franco continued to prosecute criminals until its demise. In the earlier years, some prisons were filled up to fourteen times their capacity, with prisoners hardly able to move about. People were often locked up simply for carrying a union card. Active militants were often less fortunate; thousands were shot or hanged. Two of the most able Resistance fighters, Jose Luis Facerias and Francisco Sabater Llopart (often called Sabaté), were simply shot by police forces; many anarchists met a similar fate.

The then-underground CNT was also involved. In 1962, a secret Interior Defense section was formed to coordinate actions of the resistance.

The Anarchist Black Cross was re-activated in the late 1960s by Albert Meltzer and Stuart Christie to help anarchist prisoners during Franco's reign.[53] In 1969, Miguel García García became International Secretary of the ABC.

Today[edit]

The CNT is still active today. Their influence, however, is limited. The CNT, in 1979, split into two factions: CNT/AIT and CNT/U. The CNT/AIT claimed the original "CNT" name, which led the CNT/U to change its name to Confederación General del Trabajo (CGT) in 1989, which retains most of the CNT's principles. The CGT is much larger, with perhaps 50,000 members (although it represents as many as two million workers), and is currently the third largest union in Spain. An important cause for the split and the main practical difference between the two trade unions today is that the CGT participates, just like any other Spanish trade union, in elecciones sindicales, where workers choose their representatives who sign their collective bargaining agreements. CGT has an important number of representatives in, for example, SEAT, the Spanish car manufacturer and still the largest enterprise in Catalonia and also in the public railroad system, e.g., it holds the majority in Barcelona's underground. CNT does not participate in elecciones sindicales and criticizes this model. The CNT–CGT split has made it impossible for the government to give back the unions' important facilities that belonged to them before Franco's regime seized them and used them for their only legal trade union, a devolution also still pending in part for some of the other historical political parties and worker organizations.[54]

During the first years of the 2000s, the Iberian Federation of Libertarian Youth in Spain started to adopt insurrectionary anarchist ideals, and distancing from anarcho-syndicalism became more prevalent due to the influence of black blocs in alterglobalization protests and examples of anarchist insurrection from Italy and Greece. However, around 2002 - 2003 it was subject to state repression, driving it into inactivity.[55]

A new generation of anarchist youth decided to re-establish the FIJL in 2006, deviating from its predecessor in identifying as a formal organisation (something insurrectionary anarchism disavows), as well as being sympathetic to anarcho-syndicalism, although this did not prevent it from criticizing institutions such as the CNT.[56][57] In the year 2007 it claimed itself to be the direct continuation of the previous FIJL, since it did not have news from the insurrectionist organization. However, after the publishing of a communique by FIJL,[55] it rebranded itself the "Iberian Federation of Anarchist Youth" (Federación Ibérica de Juventudes Anarquistas or FIJA), still claiming to be descended from, and continuing in the spirit of, 90s FIJL.[58] They publish a newspaper called El Fuelle (The Bellows).

In March 2012, the insurrectionist FIJL of the 1990s announced its dissolution,[59] and so FIJA reclaimed the FIJL name.[60] Today, the FIJL has presence in Asturias, Cádiz, Donosti, Granada, Lorca (Murcia) and Madrid.[61]

Violence[edit]

Although many anarchists were opposed to the use of force, some militants did use violence and terrorism to further their agendas. This "propaganda of the deed" first became popular in the late 19th century. This was before the rise of syndicalism as an anarchist tactic, and after a long history of police repression that led many to despair.

Los Desheredados (English translation: "the Disinherited"), were a secret group advocating violence and said to be behind a number of murders. Another group, Mano Negra (Black Hand), was also rumoured to be behind various assassinations and bombings, although there is some evidence that the group was a sensational myth created by police in the Civil Guard (La Guardia Civil), notorious for their brutality; in fact, it is well known that police invented actions by their enemies, or carried them out themselves, as a tool of repression. Los Solidarios and Agrupación de los Amigos de Durruti (Friends of Durruti) were other groups that used violence as a political weapon. The former group was responsible for the robbery of Banco de Bilbao which gained 300,000 pesetas, and the assassination of the Cardinal Archbishop of Zaragoza Juan Soldevilla y Romero, who was reviled as a particularly reactionary cleric. Los Solidarios stopped using violence with the end of the Primo de Rivera dictatorship, when anarchists had more opportunities to work aboveground.

In later years, anarchists were responsible for a number of church burnings throughout Spain. The Church, a powerful, usually right-wing political force in Spain, was always hated by anti-authoritarians. At this time, their influence was not as grand as in the past, but a rise of anti-Christian sentiment coincided with their perceived or real support of fascism. Many of the burnings were not committed by anarchists. However, anarchists were often used as a scapegoat by the authorities.

Rarely was violence directed towards civilians. However, there are a few recorded cases in which anarchists enforced their own beliefs with violence; one observer reports incidents in which pimps and drug dealers were shot on the spot. Forced collectivization, while exceedingly rare, did occur on several occasions when ideals were dropped in favor of wartime pragmatism. In general, though, individual holdings were respected by anarchists who opposed coercive violence more vigorously than small-scale property possession.

Despite the violence of some, many anarchists in Spain adopted an ascetic lifestyle in line with their libertarian beliefs. Smoking, drinking, gambling, and prostitution were widely looked down upon. Anarchists avoided dealing with institutions they proposed to fight against: most did not enter into marriages, go to State-run schools (libertarian schools, like the Catalan Ferrer's Escuela Moderna, were popular), or attempt to aggrandize their personal wealth. This moralism starkly contrasts with the popular view of anarchists as anomic firebrands, but also is part of another stereotype that the anarchism in Spain was a millenarian pseudo-religion.

Feminism[edit]

Feminism has historically played a role alongside the development of anarchism; Spain is no exception. The CNT's founding congress placed special emphasis on the role of women in the labor force and urged an effort to recruit them into the organization. There was also a denunciation of the exploitation of women in society and of wives by their husbands.

Women's rights had been integral in anarchist ideas such as coeducation, the abolition of marriage, and abortion rights, amongst others; these were quite radical ideas in traditionally Catholic Spain. Women had played a large part in many of the struggles, even fighting alongside their male comrades on the barricades. However, they were often marginalized; for example, women often were paid less in the agrarian collectives and had less visible roles in larger anarchist organizations.

A Spanish anarchist group known as Mujeres Libres (Free Women) provided day-care, education, maternity centers, and other services for the benefit of women. The group had a peak membership of between 20,000 and 38,000. Its first national congress, held in 1937, with delegations from over a dozen different cities representing about 115 smaller groups. The statutes of the organization declared its purpose as being "a. To create a conscious and responsible feminine force that will act as a vanguard of progress; b. To establish for this purpose schools, institutes, lectures, special courses, etc., to train the woman and emancipate her from the triple slavery to which she has been and still is submitted: the slavery of ignorance, the slavery of being a woman, and the slavery of being a worker."

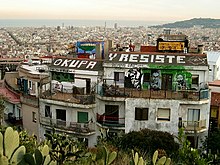

Eskalera Karakola is a current squat in Madrid, Spain, which is held by feminists and works on autogestion principles. It was situated in the Lavapiés barrio from 1996 to 2005, and is now in Calle Embajador. The squat organizes activities focussing on domestic violence and women's precarity in post-industrial capitalism. In 2002, it created a Female Workers' Laboratory (Laboratorio de Trabajadoras), and has carried out anti-racist activities, in particular with female immigrants, since 1998. Eskalera Karakola also took part in the organization of the LGBT Pride and the forum "Women and Architecture". It participated in alter-globalization events such as the European Social Forum and is part of the European nextGENDERation network.[62] It publishes a review titled Mujeres Preokupando (Concerned Women).

See also[edit]

- Antorcha, a 1930s anarchist newspaper from Las Palmas

- La Mano Negra, an alleged violent anarchist secret society operating in Andalusia around 1880

- Vivir la Utopia, a movie about anarchism in Spain by J. Gamero

References[edit]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Díez 2007.

- ^ Bookchin 1978, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bookchin 1978, p. 21.

- ^ George Woodcock (2004). Anarchism: a history of libertarian ideas and movements. University of Toronto Press. p. 299. ISBN 978-1-55111-629-7.

- ^ Bookchin 1978, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bookchin 1978, p. 12.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bookchin 1978, p. 15.

- ^ Tuñón de Lara, Manuel (1977) [1972]. El movimiento obrero en la historia de España. I.1832-1899 (in Spanish) (2ª ed.). Barcelona: Laia. pp. 161–162. ISBN 84-7222-331-0.

- ^ Bookchin 1978, p. 12-14.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bookchin 1978, p. 14.

- ^ Bookchin 1978, p. 14-15.

- ^ Bookchin 1978, pp. 42–43.

- ^ Bookchin 1978, pp. 43–44.

- ^ Bookchin 1978, pp. 45.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bookchin 1978, pp. 46–50.

- ^ Bookchin 1978, pp. 37–41.

- ^ Bookchin 1978, pp. 46.

- ^ Bookchin 1978, p. 51.

- ^ Bookchin 1978, pp. 51–52.

- ^ Bookchin 1978, pp. 52–53.

- ^ Bookchin 1978, pp. 53–54.

- ^ Bookchin 1978, pp. 54–55.

- ^ Engels, Friedrich (1973). "1873: The Bakuninists at Work". Marxists Internet Archive. Der Volksstaat, 31 October, 2–5 November 1873. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- ^ George Woodcock. Anarchism: a history of libertarian movements. Pg. 357

- ^ "Anarchism" at the Encyclopædia Britannica online.

- ^ (1998) Bookchin, Murray. The Spanish Anarchists 111-114 pp

- ^ Gómez Casas 1986, p. 44.

- ^ Kelsey, Graham (1991). Anarchosyndicalism, Libertarian Communism and the State: The CNT in Zaragoza and Aragon, 1930-1937. Kluwer Academic Publishers. p. 98.

- ^ Comuniello, Sofia (August 1992). "Getting to know Durruti". Correo@ (20): 16–17 – via Spunk Library.

- ^ Kelsey, Graham (1991). Anarchosyndicalism, Libertarian Communism and the State: The CNT in Zaragoza and Aragon, 1930-1937. Kluwer Academic Publishers. p. 110.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Díez 2006.

- ^ Díez 2001.

- ^ guest8dcd3f (2009-07-22). "Anarquismo Miguel Gimenez Igualada". Retrieved 20 March 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Díez 2006: "Entre los redactores y colaboradores de Al Margen, que trasladará su redacción a Elda, en Alicante, encontraremos a Miguel Giménez Igualada..."

- ^ Díez 2006: "A partir de la década de los treinta, su pensamiento empieza a derivar hacia el individualismo, y como profundo estirneriano tratará de impulsar una federación de individualistas"

- ^ ""Stirner" by Miguel Giménez Igualada" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-09-17. Retrieved 2010-07-09.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Anarchism - Nudism, Naturism" by Carlos Ortega at Asociacion para el Desarrollo Naturista de la Comunidad de Madrid. Published on Revista ADN. Winter 2003

- ^ Ness, Immanuel, ed. (2009). Zisly, Henri (1872–1945) : The International Encyclopedia of Revolution and Protest : International Encyclopedia of Revolution and Protest. John Wiley & Sons. doi:10.1002/9781405198073. ISBN 9781405198073.

- ^ "Robert Brentano, Fernando Fernán-Gómez, Guy Debord, Leo Tolstoy, Alexander Berkman, Émile Gravelle, Louise Michel, Santiago Salvador Franch, Mollie Steimer, Ricardo Flores Magón, Dorothy Day, Joffre Stewart, on this day in recovered history November 21". Archived from the original on 1 July 2016. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- ^ Arturo. "Los origenes del naturismo libertario". Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Isaac Puente. El Comunismo Libertario y otras proclamas insurreccionales y naturistas.

- ^ Íñiguez, Miguel, ed. (2004). Anarquismo y Naturismo: El Caso de Isaac Puente. Vitoria: Asociación Isaac Puente.

- ^ Isaac Puente. El Comunismo Libertario y otras proclamas insurreccionales y naturistas. pg. 4

- ^ Díez 2007: "De hecho, el documento de Isaac Puente se convirtió en dictamen oficial aprobado en el Congreso Extraordinario Confederal de Zaragoza de 1936 que servía de base para fijar la línea política de la CNT respecto a la organización social y política futura. Existe una versión resumida en Íñiguez (1996), pp. 31-35. La versión completa se puede encontrar en las actas oficiales del congreso, publicadas en CNT: El Congreso Confederal de Zaragoza, Zeta, Madrid, 1978, pp. 226-242."

- ^ "Y complementarlos puesto que se ocupan de aspectos distintos, –el uno redime al ser vivo, el otro al ser social"Isaac Puente. El Comunismo Libertario y otras proclamas insurreccionales y naturistas.

- ^ Anarchism: From theory to practice by Daniel Guérin

- ^ The Spanish Civil War, documentary, Granada.

- ^ Beevor, Antony (2012-08-23). The Battle for Spain: The Spanish Civil War 1936-1939. Orion. ISBN 978-1-78022-453-4.

- ^ "Speech at the International Workingmen's Association, Paris, 1937". Archived from the original on 30 December 2007. Retrieved 7 January 2008.

- ^ Hugh Purcell, p. 98, Colonel Vicente Rojo Lluch as quoted in Stanley G. Payne, The Spanish Revolution, (1970)

- ^ "An Anarchist Perspective on the Spanish Civil War". Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- ^ D. Phillips, Jr, William; Rahn Phillips, Carla (2010). A Concise History of Spain. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1139788908.

- ^ Meltzer, Albert (1996). "XIII". I Couldn't Paint Golden Angels. Edinburgh: AK Press. pp. 200–201. ISBN 978-1-873176-93-1.

- ^ "Infoshop News - The Spanish CGT - The New Anarcho-syndicalism". Archived from the original on May 11, 2005.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Comunicado de la Federación Ibérica de Juventudes Libertarias (FIJL)". Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- ^ Anarchist Youths of León, "La Teoría de Cuerdas del Sindicalismo" ("Syndicalism's String Theory") Archived copy. Archived from the original the 15th of April, 2013.

- ^ Black Flag Group "Lo que es y no es el 19 de julio" ("What is and isn't the 19th of July")

- ^ "Nace la Federación Ibérica de Juventudes Anarquistas". alasbarricadas.org. 11 August 2007. Retrieved 3 February 2014.

- ^ "Comunicado de disolución de la Federación Ibérica de Juventudes Libertarias (FIJL)". Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- ^ "Federación Ibérica de Juventudes Libertarias – F.I.J.L". nodo50.org. 5 April 2012. Archived from the original on 4 June 2012. Retrieved 3 February 2014.

- ^ "Directorio de la Federación Ibérica de Juventudes Libertarias". Archived from the original on June 4, 2012.

- ^ "脱毛エステの口コミ人気NO1は?※調査してみた!". Retrieved 20 March 2015.

Bibliography[edit]

- An "Uncontrollable" from the Iron Column (2003) [1937]. A Day Mournful and Overcast. London: Kate Sharpley Library. ISBN 1-873605-33-1. OCLC 55624636.

- Ackelsberg, Martha (2005). Free Women of Spain: Anarchism and the Struggle for the Emancipation of Women. Oakland: AK Press. ISBN 1-902593-96-0. OCLC 492943653.

- Alexander, Robert (1999). The Anarchists in the Spanish Civil War. London: Janus. ISBN 1-85756-400-6. OCLC 43717219.

- Beevor, Antony (2001) [1982]. The Spanish Civil War. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-100148-8. OCLC 46321088.

- Bookchin, Murray (1978). The Spanish Anarchists: The Heroic Years, 1868–1936. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 0-06-090607-3. OCLC 4604735.

- Bookchin, Murray (1994). To Remember Spain. Edinburgh: AK Press. ISBN 1-873176-87-2. OCLC 231645582..

- Boyd, Carolyn P. (1976). "The Anarchists and Education in Spain, 1868-1909". The Journal of Modern History. 48 (4): 125–170. doi:10.1086/241533. ISSN 0022-2801. JSTOR 1877306. OCLC 5545665264. S2CID 144384298.

- Brenan, Gerald (2009) [1943]. The Spanish Labyrinth. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-39827-5. OCLC 934347541.

- Caplan, Bryan (1996). "The Anarcho-Statists of Spain: An Historical, Economic, and Philosophical Analysis of Spanish Anarchism". George Mason University. Retrieved July 9, 2017.

- Gómez Casas, Juan (1986). Anarchist organisation : the history of the F.A.I. Montréal: Black Rose Books. ISBN 0-920057-40-3.

- Chomsky, Noam (1987). "Objectivity and Liberal Scholarship". In Peck, James (ed.). The Chomsky Reader. New York: Pantheon Books. ISBN 0394751736. OCLC 935522790.

- Christie, Stuart (2008). We, The Anarchists! A Study Of The Iberian Anarchist Federation (FAI) 1927–1937. Edinburgh: AK Press. ISBN 978-1904859758. OCLC 443786153.

- Díez, Xavier (2001). Utopia sexual a la premsa anarquista de Catalunya: la revista Ética-Iniciales, 1927-1937 (in Catalan). Lleida. ISBN 978-84-7935-715-3. OCLC 469334328.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Díez, Xavier (2006). "La insumisión voluntaria. El anarquismo individualista español durante la dictadura y la segund arepública (1923-1938)". Germinal: Revista de Estudios Libertarios (in Spanish) (1). Madrid: 23–58. ISSN 1886-3019. OCLC 756095520.

- Díez, Xavier (2007). El anarquismo individualista en España 1923-1938. Barcelona: Virus Editorial. ISBN 978-84-96044-87-6. OCLC 914865324.

- Esenwein, George Richard (1989). Anarchist Ideology and the Working-class Movement in Spain, 1868–1898. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-06398-3. OCLC 470814010.

- Fraser, Ronald (1979). Blood of Spain. New York: Pantheon Books. ISBN 0-394-73854-3. OCLC 954289856.

- Fremion, Yves (2002) [1980]. "The Spanish Revolution and the Durruti Column". Orgasms of History: 3000 Years of Spontaneous Revolt. Edinburgh: AK Press. ISBN 1-902593-34-0. OCLC 1112570340..

- Garcia, Miguel (2002). Looking Back After Twenty Years of Jail. London: Kate Sharpley Library. ISBN 1-873605-03-X. OCLC 1179841539.

- Goldman, Emma (2006) [1983]. Vision on Fire: Emma Goldman on the Spanish Revolution (Second ed.). Edinburgh: AK Press. ISBN 1904859577. OCLC 974188207.

- Guillamón, Agustin (1996). The Friends of Durruti Group 1937-1939. Edinburgh: AK Press. ISBN 1-873176-54-6. OCLC 932378848.

- Íñiguez, Miguel (2008). Enciclopedia histórica del anarquismo español. Vitoria-Gasteiz: Asociación Isaac Puente. ISBN 978-84-612-4219-1. OCLC 716810373.

- Meltzer, Albert, ed. (1978). A New World in Our Hearts: The Faces of Spanish Anarchism. Sanday: Cienfuegos Press. ISBN 0904564193. OCLC 1074878778.

- Oehler, Hugo (1988) [1937]. "Barricades in Barcelona". Revolutionary History. 1 (2). London: Socialist Platform. ISSN 0953-2382. OCLC 989960086.

- Orwell, George (1952) [1938]. Homage to Catalonia. New York: Harcourt. ISBN 0-15-642117-8. OCLC 1129324667.

- Crossey, Ciaran (20 January 2008). "Patrick Joseph Read — Irish Anarchist in Spanish Civil War". Retrieved 3 August 2021.

- Payne, Stanley G. (1970). The Spanish Revolution. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 0297001248. OCLC 906044930.

- Peirats, José (1998) [1990]. Anarchists in the Spanish Revolution. London: Freedom Press. ISBN 0-900384-53-0. OCLC 634571715.

- Peirats, José (2011) [2001]. The CNT in the Spanish Revolution. Oakland: PM Press. ISBN 1-901172-05-8 (vol. 1); ISBN 1-873976-24-0 (vol. 2); ISBN 1-873976-29-1 (vol.3). all from ChristieBooks.

- Téllez, Antonio (1998) [1974]. Sabaté: Guerrilla Extraordinary. Edinburgh: AK Press. ISBN 1-902593-10-3. OCLC 47192670.

- Téllez, Antonio (1994). The Anarchist Resistance to Franco. London: Kate Sharpley Library. ISBN 1-873605-65-X. OCLC 40183487.

- Termes, Josep (2000) [1971]. Anarquismo y sindicalismo en España: la Primera Internacional (1864–1881) (in Spanish). Barcelona: Critica. ISBN 8484320588. OCLC 469664394.