Christian Science

| Christian Science | |

|---|---|

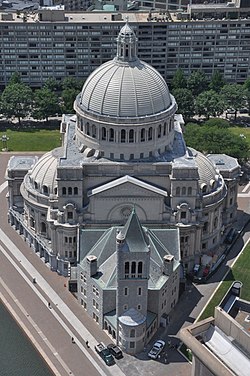

The First Church of Christ, Scientist at the Christian Science Center in Boston with the original Mother Church (1894) in the foreground and the Mother Church Extension (1906) behind it.[1] | |

| Scripture | Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures by Mary Baker Eddy and the Bible |

| Theology | "Basic teachings", Church of Christ, Scientist |

| Founder | Mary Baker Eddy (1821–1910) |

| Members | Estimated 106,000 in the United States in 1990[2] and under 50,000 in 2009;[3] according to the church, 400,000 worldwide in 2008.[n 1] |

| Official website | christianscience.com |

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Christian Science |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Christianity |

|---|

|

Christian Science is a set of beliefs and practices which are associated with members of the Church of Christ, Scientist. Adherents are commonly known as Christian Scientists or students of Christian Science, and the church is sometimes informally known as the Christian Science church. It was founded in 1879 in New England by Mary Baker Eddy, who wrote the 1875 book Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures, which outlined the theology of Christian Science.[n 2] The book became Christian Science's central text, along with the Bible, and by 2001 had sold over nine million copies.[5]

Eddy and 26 followers were granted a charter by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts in 1879 to found the "Church of Christ (Scientist)"; the church would be reorganized under the name "Church of Christ, Scientist" in 1892.[6] The Mother Church, The First Church of Christ, Scientist, was built in Boston, Massachusetts, in 1894.[7] Christian Science became the fastest growing religion in the United States, with nearly 270,000 members there by 1936, a figure that had declined to just over 100,000 by 1990[8] and reportedly to under 50,000 by 2009.[3] The church is known for its newspaper, The Christian Science Monitor, which won seven Pulitzer Prizes between 1950 and 2002, and for its public Reading Rooms around the world.[n 3]

Eddy described Christian Science as a return to "primitive Christianity and its lost element of healing".[10] There are key differences between Christian Science theology and that of traditional Christianity.[11] In particular, adherents subscribe to a radical form of philosophical idealism, believing that reality is purely spiritual and the material world an illusion.[12] This includes the view that disease is a mental error rather than physical disorder, and that the sick should be treated not by medicine but by a form of prayer that seeks to correct the beliefs responsible for the illusion of ill health.[13][14]

The church does not require that Christian Scientists avoid medical care—adherents use dentists, optometrists, obstetricians, physicians for broken bones, and vaccination when required by law—but maintains that Christian Science prayer is most effective when not combined with medicine.[15][16] The reliance on prayer and avoidance of medical treatment has been blamed for the deaths of several adherents and their children. Between the 1880s and 1990s, parents and others were prosecuted for, and in a few cases convicted of, manslaughter or neglect.[17]

Overview[edit]

Metaphysical family[edit]

Several periods of Protestant Christian revival nurtured a proliferation of new religious movements in the United States.[18] In the latter half of the 19th century these included what came to be known as the metaphysical family: groups such as Christian Science, Divine Science, the Unity School of Christianity, and (later) the United Church of Religious Science.[n 4] From the 1890s the liberal section of the movement became known as New Thought, in part to distinguish it from the more authoritarian Christian Science.[24]

The term metaphysical referred to the movement's philosophical idealism, a belief in the primacy of the mental world.[n 5] Adherents believed that material phenomena were the result of mental states, a view expressed as "life is consciousness" and "God is mind." The supreme cause was referred to as Divine Mind, Truth, God, Love, Life, Spirit, Principle or Father–Mother, reflecting elements of Plato, Hinduism, Berkeley, Hegel, Swedenborg, and transcendentalism.[26][27]

The metaphysical groups became known as the mind-cure movement because of their strong focus on healing.[28][n 6] Medical practice was in its infancy, and patients regularly fared better without it. This provided fertile soil for the mind-cure groups, who argued that sickness was an absence of "right thinking" or failure to connect to Divine Mind.[31] The movement traced its roots in the United States to Phineas Parkhurst Quimby (1802–1866), a New England clockmaker turned mental healer. His advertising flyer, "To the Sick" included this explanation of his clairvoyant methodology: ". . .he gives no medicines and makes no outward applications, but simply sits down by the patients, tells them their feelings and what they think is their disease. If the patients admit that he tells them their feelings, &c., then his explanation is the cure; and, if he succeeds in correcting their error, he changes the fluids of the system and establishes the truth, or health. The Truth is the Cure. This mode of practise applies to all cases. If no explanation is given, no charge is made, for no effect is produced."[32][n 7] Mary Baker Eddy had been a patient of his (1862–1865), leading to debate about how much of Christian Science was based on his ideas.[34]

New Thought and Christian Science differed in that Eddy saw her views as a unique and final revelation.[35][n 8] Eddy's idea of malicious animal magnetism (that people can be harmed by the bad thoughts of others) marked another distinction, introducing an element of fear that was absent from the New Thought literature.[37][38] Most significantly, she dismissed the material world as an illusion, rather than as merely subordinate to Mind, leading her to reject the use of medicine, or materia medica, and making Christian Science the most controversial of the metaphysical groups. Reality for Eddy was purely spiritual.[39][n 9]

Christian Science theology[edit]

Christian Science leaders place their religion within mainstream Christian teaching, according to J. Gordon Melton, and reject any identification with the New Thought movement.[n 10] Eddy was strongly influenced by her Congregationalist upbringing.[42] According to the church's tenets, adherents accept "the inspired Word of the Bible as [their] sufficient guide to eternal Life ... acknowledge and adore one supreme and infinite God ... [and] acknowledge His Son, one Christ; the Holy Ghost or divine Comforter; and man in God's image and likeness."[43] When founding the Church of Christ, Scientist, in April 1879, Eddy wrote that she wanted to "reinstate primitive Christianity and its lost element of healing".[10] Later she suggested that Christian Science was a kind of second coming and that Science and Health was an inspired text.[n 11][46] In 1895, in the Manual of the Mother Church, she ordained the Bible and Science and Health as "Pastor over the Mother Church".[47]

Christian Science theology differs in several respects from that of traditional Christianity. Eddy's Science and Health reinterprets key Christian concepts, including the Trinity, divinity of Jesus, atonement, and resurrection; beginning with the 1883 edition, she added with a Key to the Scriptures to the title and included a glossary that redefined the Christian vocabulary.[n 10] At the core of Eddy's theology is the view that the spiritual world is the only reality and is entirely good, and that the material world, with its evil, sickness and death, is an illusion. Eddy saw humanity as an "idea of Mind" that is "perfect, eternal, unlimited, and reflects the divine", according to Bryan Wilson; what she called "mortal man" is simply humanity's distorted view of itself.[50] Despite her view of the non-existence of evil, an important element of Christian Science theology is that evil thought, in the form of malicious animal magnetism, can cause harm, even if the harm is only apparent.[51]

Eddy viewed God not as a person but as "All-in-all". Although she often described God in the language of personhood—she used the term "Father–Mother God" (as did Ann Lee, the founder of Shakerism), and in the third edition of Science and Health she referred to God as "she"—God is mostly represented in Christian Science by the synonyms "Mind, Spirit, Soul, Principle, Life, Truth, Love".[52][n 12] The Holy Ghost is Christian Science, and heaven and hell are states of mind.[n 13] There is no supplication in Christian Science prayer. The process involves the Scientist engaging in a silent argument to affirm to herself the unreality of matter, something Christian Science practitioners will do for a fee, including in absentia, to address ill health or other problems.[55] Wilson writes that Christian Science healing is "not curative ... on its own premises, but rather preventative of ill health, accident and misfortune, since it claims to lead to a state of consciousness where these things do not exist. What heals is the realization that there is nothing really to heal."[56] It is a closed system of thought, viewed as infallible if performed correctly; healing confirms the power of Truth, but its absence derives from the failure, specifically the bad thoughts, of individuals.[57]

Eddy accepted as true the creation narrative in the Book of Genesis up to chapter 2, verse 6—that God created man in his image and likeness—but she rejected the rest "as the story of the false and the material", according to Wilson.[58] Her theology is nontrinitarian: she viewed the Trinity as suggestive of polytheism.[n 14] She saw Jesus as a Christian Scientist, a "Way-shower" between humanity and God,[60] and she distinguished between Jesus the man and the concept of Christ, the latter a synonym for Truth and Jesus the first person fully to manifest it.[61] The crucifixion was not a divine sacrifice for the sins of humanity, the atonement (the forgiveness of sin through Jesus's suffering) "not the bribing of God by offerings", writes Wilson, but an "at-one-ment" with God.[62] Her views on life after death were vague and, according to Wilson, "there is no doctrine of the soul" in Christian Science: "[A]fter death, the individual continues his probationary state until he has worked out his own salvation by proving the truths of Christian Science."[13] Eddy did not believe that the dead and living could communicate.[63]

To the more conservative of the Protestant clergy, Eddy's view of Science and Health as divinely inspired was a challenge to the Bible's authority.[64] "Eddyism" was viewed as a cult; one of the first uses of the modern sense of the word was in A. H. Barrington's Anti-Christian Cults (1898), a book about Spiritualism, Theosophy and Christian Science.[65] In a few cases Christian Scientists were expelled from Christian congregations, but ministers also worried that their parishioners were choosing to leave. In May 1885 the London Times' Boston correspondent wrote about the "Boston mind-cure craze": "Scores of the most valued Church members are joining the Christian Scientist branch of the metaphysical organization, and it has thus far been impossible to check the defection."[66] In 1907 Mark Twain described the appeal of the new religion to its adherents:

[Mrs. Eddy] has delivered to them a religion which has revolutionized their lives, banished the glooms that shadowed them, and filled them and flooded them with sunshine and gladness and peace; a religion which has no hell; a religion whose heaven is not put off to another time, with a break and a gulf between, but begins here and now, and melts into eternity as fancies of the waking day melt into the dreams of sleep.

They believe it is a Christianity that is in the New Testament; that it has always been there, that in the drift of ages it was lost through disuse and neglect, and that this benefactor has found it and given it back to men, turning the night of life into day, its terrors into myths, its lamentations into songs of emancipation and rejoicing.

There we have Mrs. Eddy as her followers see her. ... They sincerely believe that Mrs. Eddy's character is pure and perfect and beautiful, and her history without stain or blot or blemish. But that does not settle it. ...[67]

History[edit]

Mary Baker Eddy and the early Christian Science movement[edit]

Mary Baker Eddy was born Mary Morse Baker on a farm in Bow, New Hampshire, the youngest of six children in a religious family of Protestant Congregationalists.[68] In common with most women at the time, Eddy was given little formal education, but read widely at home and was privately tutored.[69] From childhood she lived with protracted ill health.[70] Eddy's first husband died six months after their marriage and three months before their son was born, leaving her penniless; and as a result of her poor health she lost custody of the boy when he was four.[71] She married again, and her new husband promised to become the child's legal guardian, but after their marriage he refused to sign the needed papers and the boy was taken to Minnesota and told his mother had died.[72][n 15] Eddy, then known as Mary Patterson, and her husband moved to rural New Hampshire, where Eddy continued to suffer from health problems which often kept her bedridden.[74] Eddy tried various cures for her health problems, including conventional medicine as well as most forms of alternative medicine such as Grahamism, electrotherapy, homeopathy, hydropathy, and finally mesmerism under Phineas Quimby.[75] She was later accused by critics, beginning with Julius Dresser, of borrowing ideas from Quimby in what biographer Gillian Gill would call the "single most controversial issue" of her life.[76]

In February 1866, Eddy fell on the ice in Lynn, Massachusetts. Evidence suggests she had severe injuries, but a few days later she apparently asked for her Bible, opened it to an account of one of Jesus' miracles, and left her bed telling her friends that she was healed through prayer alone.[77] The moment has since been controversial, but she considered this moment one of the "falling apples" that helped her to understand Christian Science, although she said she did not fully understand it at the time.[78]

In 1866, after her fall on the ice, Eddy began teaching her first student and began writing her ideas which she eventually published in Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures, considered her most important work.[79] Her students voted to form a church called the Church of Christ (Scientist) in 1879, later reorganized as The First Church of Christ, Scientist, also known as The Mother Church, in 1892.[80] She founded the Massachusetts Metaphysical College in 1881 to continue teaching students,[81] Eddy started a number of periodicals: The Christian Science Journal in 1883, the Christian Science Sentinel in 1898, The Herald of Christian Science in 1903, and The Christian Science Monitor in 1908, the latter being a secular newspaper.[82] The Monitor has gone on to win seven Pulitzer prizes as of 2011.[83] She also wrote numerous books and articles in addition to Science and Health, including the Manual of The Mother Church which contained by-laws for church government and member activity, and founded the Christian Science Publishing Society in 1898 in order to distribute Christian Science literature.[82] Although the movement started in Boston, the first purpose-built Christian Science church building was erected in 1886 in Oconto, Wisconsin.[84] During Eddy's lifetime, Christian Science spread throughout the United States and to other parts of the world including Canada, Great Britain, Germany, South Africa, Hong Kong, the Philippines, Australia, and elsewhere.[85]

Eddy encountered significant opposition after she began teaching and writing on Christian Science, which only increased towards the end of her life.[86] One of the most prominent examples was Mark Twain, who wrote a number of articles on Eddy and Christian Science which were first published in Cosmopolitan magazine in 1899 and were later published as a book.[87] Another extended criticism, which again was first serialized in a magazine and then published in book form, was Georgine Milmine and Willa Cather's The Life of Mary Baker G. Eddy and the History of Christian Science which first appeared in McClure's magazine in January 1907.[88] Also in 1907, several of Eddy's relatives filed an unsuccessful lawsuit instigated by the New York World, known in the press as the "Next Friends Suit", against members of Eddy's household, alleging that she was mentally unable to manage her own affairs.[89] The suit fell apart after Eddy was interviewed in her home in August 1907 by the judge and two court appointed masters (one a psychiatrist) who concluded that she was mentally competent. Separately she was seen by two psychiatrists, including Allan McLane Hamilton, who came to the same conclusion.[90] The McClure's and New York World stories are considered to at least partially be the reason Eddy asked the church in July 1908 to found the Christian Science Monitor as a platform for responsible journalism.[91]

Eddy died two years later, on the evening of Saturday, December 3, 1910, aged 89. The Mother Church announced at the end of the Sunday morning service that Eddy had "passed from our sight". The church stated that "the time will come when there will be no more death," but that Christian Scientists "do not look for [Eddy's] return in this world."[92] Her estate was valued at $1.5 million, most of which she left to the church.[93]

Eddy's debt to Quimby[edit]

Eddy's debt to Phineas Parkhurst Quimby became the "single most controversial issue" of her life, according to Gillian Gill.[94] Quimby was not the only source Eddy stood accused of having copied; Ernest Sutherland Bates and John V. Dittemore, Bryan Wilson, Charles S. Braden and Martin Gardner identified several texts she had used without attribution.[n 16] For example, an open letter from Eddy to the church, dated September 1895 and published in Eddy's Miscellaneous Writings 1883–1896 (1897), is almost identical to Hugh Blair's essay "The Man of Integrity," published in Lindley Murray's The English Reader (1799).[98] Eddy acknowledged Quimby's influence in her early years. When a prospective student asked in 1871 whether her methods had been used before, she replied:

Never advertised, and practiced by only one individual who healed me, Dr. Quimby of Portland, ME., an old gentleman who had made it a research for twenty-five years, starting from the standpoint of magnetism thence going forward and leaving that behind. I discovered the art in a moment's time, and he acknowledged it to me; he died shortly after and since then, eight years, I have been founding and demonstrating the science.[99]

Later she drew a distinction between their methods, arguing that Quimby's involved one mind healing another, while hers depended on a connection with Divine Mind.[n 17] In February 1883, Julius Dresser, a former patient of Quimby's, accused Eddy in letters to The Boston Post of teaching Quimby's work as her own.[101] In response Eddy disparaged Quimby as a mesmerist and said she had experimented with mental healing in or around 1853, nine years before she met him.[101] She wrote later: "We caught some of his thoughts, and he caught some of ours; and both of us were pleased to say this to each other."[102]

The issue went to court in September 1883, when Eddy complained that her student Edward Arens had copied parts of Science and Health in a pamphlet, and Arens counter-claimed that Eddy had copied it from Quimby in the first place.[103][n 18] Quimby's son was so unwilling to produce his father's manuscripts that he sent them out of the country (perhaps fearing litigation with Eddy or that someone would tamper with them), and Eddy won the case.[104][105] Things were stirred up further by Eddy's pamphlet Historical Sketch of Metaphysical Healing (1885), in which she again called Quimby a mesmerist, and by the publication of Julius Dresser's The True History of Mental Healing (1887).[106]

The charge that Christian Science came from Quimby, not divine revelation, stemmed in part from Eddy's use of Quimby's manuscript (right) when teaching Sally Wentworth and others in 1868–1870.[n 19] Eddy said she had helped to fix Quimby's unpublished work, and now stood accused of having copied her own corrections.[108][n 20] Against this, Lyman P. Powell, one of Eddy's biographers, wrote in 1907 that Quimby's son held an almost identical copy, in Quimby's wife's handwriting, of the Quimby manuscript that Eddy had used when teaching Sally Wentworth. It was dated February 1862, eight months before Eddy met Quimby.[113]

In July 1904 the New York Times obtained a copy of the Quimby manuscript from Sally Wentworth's son, and juxtaposed passages with Science and Health to highlight the similarities. It also published Eddy's handwritten notes on Quimby's manuscript to show what the newspaper alleged was the transition from his words to hers.[n 21][115] Quimby's manuscripts were published in 1921. Eddy's biographers continued to disagree about his influence on Eddy. Bates and Dittemore, the latter a former director of the Christian Science church, argued in 1932 that "as far as the thought is concerned, Science and Health is practically all Quimby," except for malicious animal mesmerism.[116] Robert Peel, who also worked for the church, wrote in 1966 that Eddy may have influenced Quimby as much as he influenced her.[117] Gardner argued in 1993 that Eddy had taken "huge chunks" from Quimby, and Gill in 1998 that there were only general similarities.[118]

First prosecutions[edit]

In 1887 Eddy started teaching a "metaphysical obstetrics" course, two one-week classes. She had started calling herself "Professor of Obstetrics" in 1882; McClure's wrote: "Hundreds of Mrs. Eddy's students were then practising who knew no more about obstetrics than the babes they helped into this world."[119] The first prosecutions took place that year, when practitioners were charged with practicing medicine without a licence. All were acquitted during the trial, or convictions were overturned on appeal.[120]

The first manslaughter charge was in March 1888, when Abby H. Corner, a practitioner in Medford, Massachusetts, attended to her daughter during childbirth; the daughter bled to death and the baby did not survive. The defense argued that they might have died even with medical attention, and Corner was acquitted.[121] To the dismay of the Christian Scientists' Association (the secretary resigned), Eddy distanced herself from Corner, telling the Boston Globe that Corner had only attended the college for one term and had never entered the obstetrics class.[122]

From then until the 1990s around 50 parents and practitioners were prosecuted, and often acquitted, after adults and children died without medical care; charges ranged from neglect to second-degree murder.[123] The American Medical Association (AMA) declared war on Christian Scientists; in 1895 its journal called Christian Science and similar ideas "molochs to infants, and pestilential perils to communities in spreading contagious diseases."[124] Juries were nevertheless reluctant to convict when defendants believed they were helping the patient. There was also opposition to the AMA's effort to strengthen medical licensing laws.[125] Historian Shawn Peters writes that, in the courts and public debate, Christian Scientists and Jehovah's Witnesses linked their healing claims to early Christianity to gain support from other Christians.[126]

Vaccination was another battleground. A Christian Scientist in Wisconsin won a case in 1897 that allowed his son to attend public school despite not being vaccinated against smallpox. Others were arrested in 1899 for avoiding vaccination during a smallpox epidemic in Georgia. In 1900 Eddy advised adherents to obey the law, "and then appeal to the gospel to save ...[themselves] from any bad results."[127] In October 1902, after seven-year-old Esther Quimby, the daughter of Christian Scientists, died of diphtheria in White Plains, New York (she had received no medical care and had not been quarantined), the authorities pursued manslaughter charges. The controversy prompted Eddy to declare that "until public thought becomes better acquainted with Christian Science, the Christian Scientists shall decline to doctor infectious or contagious diseases", and from that time the church required Christian Scientists to report contagious diseases to health boards.[128]

The Christian Science movement after 1910[edit]

In the aftermath of Eddy's death some newspapers speculated that the church would fall apart, while others expected it to continue just as it had before.[129] As it was, the movement continued to grow in the first few decades after 1910.[130] The Manual of the Mother Church prohibits the church from publishing membership figures,[n 22] and it is not clear exactly when the height of the movement was. A 1936 census counted c. 268,915 Christian Scientists in the United States (2,098 per million), and Rodney Stark believes this to be close to the height.[132] However the number of Christian Science churches continued to increase until around 1960, at which point there was a reversal and since then many churches have closed their doors.[133] The number of Christian Science practitioners in the United States began to decline in the 1940s according to Stark.[134] According to J. Gordon Melton, in 1972 there were 3,237 congregations worldwide, of which roughly 2,400 were in the United States; and in the following ten years about 200 congregations were closed.[135]

During the years after Eddy's death, the church has gone through a number of hardships and controversies.[136] This included attempts to make practicing Christian Science illegal in the United States and elsewhere;[137] a period known as the Great Litigation which involved two intertwined lawsuits regarding church governance;[138] persecution under the Nazi and Communist regimes in Germany[139] and the Imperial regime in Japan;[140] a series of lawsuits involving the deaths of members of the church, most notably some children;[141] and a controversial decision to publish a book by Bliss Knapp.[142] In conjunction with the Knapp book controversy, there was controversy within the church involving The Monitor Channel, part of The Christian Science Monitor which had been losing money, and which eventually led to the channel shutting down.[143] Acknowledging their earlier mistake, of accepting a multi-million dollar publishing incentive to offset broadcasting losses, The Christian Science Board Of Directors, with the concurrence of the Trustees Of The Christian Science Publishing Society, withdrew Destiny Of The Mother Church from publication in September 2023.[144] In addition, it has since its beginning been branded as a cult by more fundamentalist strains of Christianity, and attracted significant opposition as a result.[145] A number of independent teachers and alternative movements of Christian Science have emerged since its founding, but none of these individuals or groups have achieved the prominence of the Christian Science church.[146]

Despite the hardships and controversies, many Christian Science churches and Reading Rooms remain in existence around the world,[147] and in recent years there have been reports of the religion growing in Africa, though it remains significantly behind other evangelical groups.[148][149] The Christian Science Monitor also remains a well respected non-religious paper which is especially noted for its international reporting and lack of partisanship.[150]

Healing practices[edit]

Christian Science prayer[edit]

[A]ll healing is a metaphysical process. That means that there is no person to be healed, no material body, no patient, no matter, no illness, no one to heal, no substance, no person, no thing and no place that needs to be influenced. This is what the practitioner must first be clear about.

— Practitioner Frank Prinz-Wondollek, 2011.[151]

Christian Scientists avoid almost all medical treatment, relying instead on Christian Science prayer.[152] This consists of silently arguing with oneself; there are no appeals to a personal god, and no set words.[153] Caroline Fraser wrote in 1999 that the practitioner might repeat: "the allness of God using Eddy's seven synonyms—Life, Truth, Love, Spirit, Soul, Principle and Mind," then that "Spirit, Substance, is the only Mind, and man is its image and likeness; that Mind is intelligence; that Spirit is substance; that Love is wholeness; that Life, Truth, and Love are the only reality." She might deny other religions, the existence of evil, mesmerism, astrology, numerology, and the symptoms of whatever the illness is. She concludes, Fraser writes, by asserting that disease is a lie, that this is the word of God, and that it has the power to heal.[154]

Christian Science practitioners are certified by the Church of Christ, Scientist, to charge a fee for Christian Science prayer. There were 1,249 practitioners worldwide in 2015;[155] in the United States in 2010 they charged $25–$50 for an e-mail, telephone or face-to-face consultation.[156] Their training is a two-week, 12-lesson course called "primary class", based on the Recapitulation chapter of Science and Health.[157] Practitioners wanting to teach primary class take a six-day "normal class", held in Boston once every three years, and become Christian Science teachers.[158] There are also Christian Science nursing homes. They offer no medical services; the nurses are Christian Scientists who have completed a course of religious study and training in basic skills, such as feeding and bathing.[159]

The Christian Science Journal and Christian Science Sentinel publish anecdotal healing testimonials (they published 53,900 between 1900 and April 1989),[160] which must be accompanied by statements from three verifiers: "people who know [the testifier] well and have either witnessed the healing or can vouch for [the testifier's] integrity in sharing it".[161] Philosopher Margaret P. Battin wrote in 1999 that the seriousness with which these testimonials are treated by Christian Scientists ignores factors such as false positives caused by self-limiting conditions. Because no negative accounts are published, the testimonials strengthen people's tendency to rely on anecdotes.[160] A church study published in 1989 examined 10,000 published testimonials, 2,337 of which the church said involved conditions that had been medically diagnosed, and 623 of which were "medically confirmed by follow-up examinations". The report offered no evidence of the medical follow-up.[162] The Massachusetts Committee for Children and Youth listed among the report's flaws that it had failed to compare the rates of successful and unsuccessful Christian Science treatment.[163]

Nathan Talbot, a church spokesperson, told the New England Journal of Medicine in 1983 that church members were free to choose medical care,[164] but according to former Christian Scientists those who do may be ostracized.[156] In 2010 the New York Times reported church leaders as saying that, for over a year, they had been "encouraging members to see a physician if they feel it is necessary", and that they were repositioning Christian Science prayer as a supplement to medical care, rather than a substitute. The church has lobbied to have the work of Christian Science practitioners covered by insurance.[156]

As of 2015, it was reported that Christian Scientists in Australia were not advising anyone against vaccines, and the religious exception was deemed "no longer current or necessary".[165] In 2021, a church Committee on Publication reiterated that although vaccination was an individual choice, that the church did not dictate against it, and those who were not vaccinated did not do so because of any "church dogma".[166]

Church of Christ, Scientist[edit]

Governance[edit]

In the hierarchy of the Church of Christ, Scientist, only the Mother Church in Boston, The First Church of Christ, Scientist, uses the definite article in its name. Otherwise the first Christian Science church in any city is called First Church of Christ, Scientist, then Second Church of Christ, Scientist, and so on, followed by the name of the city (for example, Third Church of Christ, Scientist, London). When a church closes, the others in that city are not renamed.[167]

Founded in April 1879, the Church of Christ, Scientist is led by a president and five-person board of directors. There is a public-relations department, known as the Committee on Publication, with representatives around the world; this was set up by Eddy in 1898 to protect her own and the church's reputation.[168] The church was accused in the 1990s of silencing internal criticism by firing staff, delisting practitioners and excommunicating members.[169]

The church's administration is headquartered on Christian Science Center on the corner of Massachusetts Avenue and Huntington Avenue, located on several acres in the Back Bay section of Boston.[170] The 14.5-acre site includes the Mother Church (1894), Mother Church Extension (1906), the Christian Science Publishing Society building (1934)—which houses the Mary Baker Eddy Library and the church's administrative staff—the Sunday School building (1971), and the Church Colonnade building (1972).[171] It also includes the 26-story Administration Building (1972), designed by Araldo Cossutta of I. M. Pei & Associates, which until 2008 housed the administrative staff from the church's 15 departments. There is also a children's fountain and a 690 ft × 100 ft (210 m × 30 m) reflecting pool.[172][173]

Manual of The Mother Church[edit]

Eddy's Manual of The Mother Church (first published 1895) lists the church's by-laws.[175] Requirements for members include daily prayer and daily study of the Bible and Science and Health.[n 23] Members must subscribe to church periodicals if they can afford to, and pay an annual tax to the church of not less than one dollar.[177]

Prohibitions include engaging in mental malpractice; visiting a store that sells "obnoxious" books; joining other churches; publishing articles that are uncharitable toward religion, medicine, the courts or the law; and publishing the number of church members.[178] The manual also prohibits engaging in public debate about Christian Science without board approval,[179] and learning hypnotism.[180] It includes "The Golden Rule": "A member of The Mother Church shall not haunt Mrs. Eddy's drive when she goes out, continually stroll by her house, or make a summer resort near her for such a purpose."[181]

Services[edit]

The Church of Christ, Scientist is a lay church which has no ordained clergy or rituals, and performs no baptisms; with clergy of other faiths often performing marriage or funeral services since they have no clergy of their own. Its main religious texts are the Bible and Science and Health. Each church has two Readers, who read aloud a "Bible lesson" or "lesson sermon" made up of selections from those texts during the Sunday service, and a shorter set of readings to open Wednesday evening testimony meetings. In addition to readings, members offer testimonials during the main portion of the Wednesday meetings, including recovery from ill health attributed to prayer. There are also hymns, time for silent prayer, and repeating together the Lord's Prayer at each service.[182]

Notable members[edit]

Notable adherents of Christian Science have included Directors of Central Intelligence William H. Webster and Admiral Stansfield M. Turner; and Richard Nixon's chief of staff H. R. Haldeman and Chief Domestic Advisor John Ehrlichman.[183] The viscountess Nancy Astor was a Christian Scientist, as was naval officer Charles Lightoller, who survived the sinking of the Titanic in 1912.[184]

Christian Science has been well represented in the film industry, including Carol Channing and Jean Stapleton;[185] Colleen Dewhurst;[186] Joan Crawford, Doris Day, George Hamilton, Mary Pickford, Ginger Rogers, Mickey Rooney;[187] Horton Foote;[188] King Vidor;[189] Robert Duvall, and Val Kilmer.[190] Those raised by Christian Scientists include jurist Helmuth James Graf von Moltke,[191] military analyst Daniel Ellsberg;[192] Ellen DeGeneres, Henry Fonda, Audrey Hepburn;[193] James Hetfield, Marilyn Monroe, Robin Williams, and Elizabeth Taylor.[188] Taylor's godfather, the British politician Victor Cazalet, was also a member of the church. Actor Anne Archer was raised within Christian Science; she left the church when her son, Tommy Davis, was a child, and both became prominent in the Church of Scientology.[194]

A conspicuous event was the death in June 1937 of actress Jean Harlow, who died of kidney failure at age 26. Her mother, known as Mama Jean, was a recent convert to Christian Science and did on at least two occasions attempt to block conventional medical treatment for her daughter. Fellow actors and studio executives intervened, and Harlow received medical treatment, although in 1937, nothing could be done for kidney failure and she perished.[195][196][n 24]

Christian Science Publishing Society[edit]

The Christian Science Publishing Society publishes several periodicals, including the Christian Science Monitor, winner of seven Pulitzer Prizes between 1950 and 2002. This had a daily circulation in 1970 of 220,000, which by 2008 had contracted to 52,000. In 2009 it moved to a largely online presence with a weekly print run.[197] In the 1980s the church produced its own television programs, and in 1991 it founded a 24-hour news channel, which closed with heavy losses after 13 months.[198]

The church also publishes the weekly Christian Science Sentinel, the monthly Christian Science Journal, and the Herald of Christian Science, a non-English publication. In April 2012 JSH-Online made back issues of the Journal, Sentinel and Herald available online to subscribers.[199]

Works by Mary Baker Eddy[edit]

- Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures (1875)

- Christian Healing (1880)

- The People's Idea of God: Its Effect on Health and Christianity (1883)

- Historical Sketch of Metaphysical Healing (1885)

- Defence of Christian Science (1885)

- No and Yes (1887)

- Rudiments and Rules of Divine Science (1887)

- Unity of Good and Unreality of Evil (1888)

- Retrospection and Introspection (1891)

- Christ and Christmas (1893)

- Rudimental Divine Science (1894)

- Manual of The Mother Church (1895)

- Pulpit and Press (1895)

- Miscellaneous Writings, 1883–1896 (1897)

- Christian Science versus Pantheism (1898)

- The Christian Science Hymnal (1898)

- Christian Healing and the People's Idea of God (1908)

- Poems (1910)

- The First Church of Christ, Scientist, and Miscellany (1913)

- Prose Works Other than Science and Health (1925)

See also[edit]

- Efficacy of prayer

- Faith healing

- Magical thinking

- New religious movement

- Principia College

- Therapeutic nihilism

Citations[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ PBS, August 2008: "The church estimates it has about 400,000 members worldwide, but independent studies put membership at around 100,000."[4]

- ^ The book was originally just called Science and Health; the subtitle with a Key to the Scriptures was added in 1883 and was later amended to with Key to the Scriptures.[citation needed]

- ^ In April 2010, the Christian Science Journal listed 1,068 Reading Rooms in the United States and 489 elsewhere.[9]

- ^ Dawn Hutchinson, 2014: "Scholars of American religious history have used the term "New Thought" to refer either to individuals and churches that officially joined the International New Thought Alliance (INTA) or to American metaphysical religions affiliated with Phineas Quimby, Mary Baker Eddy, and Emma Curtis Hopkins. New Thought writers shared the idea that God is Mind."[19] John Saliba, 2003: "The Christian Science–Metaphysical Family. This family, known also as 'New Thought' in academic literature, stresses the need to understand the functioning of the human mind in order to achieve the healing of all human ailments. ... Metaphysics/New Thought is a nineteenth-century movement and is exemplified by such groups as the Unity School of Christianity, the United Church of Religious Science, Divine Science Federation International, and Christian Science."[20] James R. Lewis, 2003: "Groups in the metaphysical (Christian Science–New Thought) tradition ... usually claim to have discovered spiritual laws which, if properly understood and applied, transform and improve the lives of ordinary individuals ..."[21] John K. Simmons, 1995: "While members, past and present, of the Christian Science movement understandably claim Mrs. Eddy's truths to be part of a unique and final religious revelation, most outside observers place Christian Science in the metaphysical family of religious organizations ..."[22] Charles S. Braden, 1963: "[I]t was in America that [mesmerism] ... gave rise to a complex of religious faiths varying from one another in significant ways, but all agreeing upon the central fact that healing and for that matter every good thing is possible through a right relationship with the ultimate power in the Universe, Creative Mind—called God, Principle, Life, Wisdom ..."This broad complex of religions is sometimes described by the rather general term 'metaphysical' ... The general movement has proliferated in many directions. Two main streams seem most vigorous: one is called Christian Science; the other, which no single name adequately describes, has come rather generally to be known as New Thought."[23]

- ^ John K. Simmons, 1995: "The broad descriptive term 'metaphysical' is not used in a manner common to the trained philosopher. Instead, it denotes the primacy of Mind as the controlling factor in human experience. At the heart of the metaphysical perspective is the theological/ontological affirmation that God is perfect Mind and human beings, in reality, exist in a state of eternal manifestation of that Divine Mind."[25]

- ^ William James, 1902: "To my mind a current far more important and interesting religiously ... I will give the title of the Mind-Cure movement. There are various sects of this "New Thought" ... but their agreements are so profound that their differences may be neglected for my present purposes ...".[29] "Christian Science so-called, the sect of Mrs. Eddy, is the most radical branch of mind-cure in its dealings with evil."[30]

- ^ Philip Jenkins, 2000: "Christian Science and New Thought both emerged from a common intellectual background in mid-nineteenth-century New England, and they shared many influences from an older mystical and magical fringe, including Swedenborgian teachings, Mesmerism, and Transcentalism. The central figure and prophet of the emerging synthesis was Phineas P. Quimby, 'the John the Baptist of Christian Science,' whose faith-healing work began in 1838. Quimby and his followers taught the overwhelming importance of thought in shaping reality, a message that was crucial for healing. If disease existed only as thought, then only by curing the mind could the body be set right: disease was a matter of wrong belief."[33]

- ^ Meredith B. McGuire, 1988: "The most familiar offshoot of the metaphysical movement ... is Christian Science, which was based upon a more extreme interpretation of metaphysical healing than that of the New Thought groups. ... Christian Science is unlike New Thought and other metaphysical movements of that era in that Mary Baker Eddy successfully arrogated to herself all teaching authority, centralized decision-making and organizational power, and developed the movement's sectarian character."[36]

- ^ Charles S. Braden, 1963: "Mary Baker Eddy pushed the postulates of positive thinking to their absolute limit. ... She proposed not merely that the spiritual overshadows the material, but that the material world does not exist. The world of our senses is but an illusion of our minds. If the material world causes us pain, grief, danger and even death, that can be changed by changing our thoughts."[40]

Roy M. Anker, 1999: " ... Mary Baker Eddy, the founder of Christian Science (denominationally known as the Church of Christ, Scientist), the most prominent, successful, controversial, and distinctive of all the groups whose inspiration scholars trace to the healing and intellectual influence of Quimby."[41]

- ^ Jump up to: a b J. Gordon Melton, 1992: "Almost as much as the medical controversy, charges of heresy from orthodox Christian churches have hounded the Church. Leaders of Christian Science insist that they are within the mainstream of Christian teachings, a concern which leads to their strong resentment of any identification with the New Thought movement, which they see as having drifted far from their central Christian affirmations. At the same time, strong differences with traditional Christian teachings concerning the Trinity, the unique divinity of Jesus Christ, atonement for sin, and the creation are undeniable. While using Christian language, Science and Health with Key to Scriptures and Eddy's other writings radically redefine basic theological terms, usually by the process commonly called allegorization. Such redefinitions are most clearly evident in the glossary to Science and Health (pages 579–599)."[48]

Rodney Stark, 1998: "But, of course, Christian Science was not just another Protestant sect. Like Joseph Smith, Mary Baker Eddy added too much new religious culture for her movement to qualify fully as a member of the Christian family—as all the leading clerics of the time repeatedly and vociferously pointed out. However, unlike Madame Blavatsky's Theosophical Society, and like the Mormons, Christian Science retained an immense amount of Christian culture. These continuities allowed converts from a Christian background to preserve a great deal of cultural capital."[49]

- ^ Mary Baker Eddy, 1891: "The second appearing of Jesus is, unquestionably, the spiritual advent of the advancing idea of God, as in Christian Science."[44]

Eddy, January 1901: "I should blush to write of Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures as I have, were it of human origin, and I, apart from God, its author. But, as I was only a scribe echoing the harmonies of heaven in divine metaphysics, I cannot be super-modest in my estimate of the Christian Science textbook."[45]

- ^ Eddy, Science and Health: "Question. — What is God?" Answer. — God is incorporeal, divine, supreme, infinite Mind, Spirit, Soul, Principle, Life, Truth, Love."[53]

- ^ Wilson 1961: "[T]he Holy Ghost is understood to be Christian Science—the promised Comforter." "Heaven and Hell are understood to be mental states ..."[54]

- ^ Eddy, Science and Health: "The theory of three persons in one God (that is, a personal Trinity or Tri-unity) suggests polytheism, rather than the one ever-present I AM."[59]

- ^ Per the legal doctrine of coverture, women in the United States could not then be their own children's guardians.Harvard Business School, 2010: "A married woman or feme covert was a dependent, like an underage child or a slave, and could not own property in her own name or control her own earnings, except under very specific circumstances. When a husband died, his wife could not be the guardian to their under-age children."[73]

- ^ The writers whose work Eddy was accused of having used include John Ruskin, Thomas Carlyle, Charles Kingsley and Henri-Frédéric Amiel.[95] According to Bates and Dittemore 1932, an essay, "Taking Offense," was printed as one of Eddy's when it had first been published anonymously by an obscure newspaper.[96] Eddy was also accused, by Walter M. Haushalter in his Mrs. Eddy Purloins from Hegel, Boston: A. A. Beauchamp, 1936, of having copied material from "The Metaphysical Religion of Hegel" (1866), an essay by Francis Lieber.[97]

- ^ Eddy, Miscellaneous Writings, 1883–1896, 1897: "A 'mind-cure' is a matter-cure. [...] The Theology of Christian Science is based on the action of the divine Mind over the human mind and body; whereas, 'mind-cure' rests on the notion that the human mind can cure its own disease, or that which it causes"[100]

- ^ The pamphlet was Theology, or the Understanding of God as Applied to Healing the Sick (1881). Arens credited Quimby, the Gottesfreunde, Jesus, and "some thoughts contained in a work by Eddy".

- ^ Ernest Sutherland Bates and John V. Dittemore, 1932: The title page stated "Extracts from Dr. P. P. Quimby's writings." On the next page there was a title, "The Science of Man or the principle which controls all phenomena." The preface was signed Mary M. Glover. A note in the margin said, "P. P. Q's mss," then Quimby's manuscript followed.[107]

- ^ Eddy, February 1899: "Quotations have been published, purporting to be Dr. Quimby's own words, which were written while I was his patient in Portland and holding long conversations with him on my views of mental therapeutics. Some words in these quotations certainly read like words that I said to him, and which I, at his request, had added to his copy when I corrected it. In his conversations with me and in his scribblings, the word science was not used at all, till one day I declared to him that back of his magnetic treatment and manipulation of patients, there was a science, and it was the science of mind, which had nothing to do with matter, electricity, or physics."[109]

Eddy, 1889: "Mr. Quimby's son has stated ... that he has in his possession all his father's written utterances; and I have offered to pay for their publication, but he declines to publish them; for their publication would silence the insinuation that Mr. Quimby originated the system of healing which I claim to be mine."[110]

Eddy, 1891: "In 1870 I copyrighted the first publication on spiritual, scientific Mind-healing, entitled The Science of Man. This little book is converted into the chapter on Recapitulation in Science and Health. It was so new—the basis it laid down for physical and moral health was so hopelessly original—that I did not venture upon its publication until later ...".[111] "Five years after taking out my first copyright, I taught the Science of Mind-healing, alias Christian Science, by writing out my manuscripts for students and distributing them unsparingly. This will account for certain published and unpublished manuscripts extant, which the evil-minded would insinuate did not originate with me."[112] - ^ New York Times, July 10, 1904: The similarities included "Error is sickness, Truth is health" (Quimby manuscript), "Sickness is part of the error which Truth casts out" (Science and Health); "Truth is God" (Quimby), "Truth is God" (S&H); "Error is matter" (Quimby), "Matter is mortal error" (S&H); "Matter has no intelligence" (Quimby), "The fundamental error of mortal man is the belief that matter is intelligent" (S&H).[114]

- ^ Manual of the Mother Church: "Christian Scientists shall not report for publication the number of the members of The Mother Church, nor that of the branch churches. According to the Scripture they shall turn away from personality and numbering the people."[131]

- ^ Members are expected to pray each day: "Thy kingdom come; let the reign of divine Truth, Life, and Love be established in me, and rule out of me all sin; and may Thy Word enrich the affections of all mankind, and govern them!"[176]

- ^ Wikipedia's Jean Harlow page dismisses this rumor and says she was consistently attended by physicians.

References[edit]

- ^ "Christian Science Center Complex" Archived 2015-09-23 at the Wayback Machine, Boston Landmarks Commission, Environment Department, City of Boston, January 25, 2011 (hereafter Boston Landmarks Commission 2011), pp. 6–12.

- ^ Stark, Rodney (1998). "The Rise and Fall of Christian Science". Journal of Contemporary Religion. 13 (2): (189–214), 191. doi:10.1080/13537909808580830.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Prothero, Donald; Callahan, Timothy D. (2017). UFOs, Chemtrails, and Aliens: What Science Says. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. p. 165.

- ^ Valente, Judy (August 1, 2008). "Christian Science Healing". PBS.

- ^ Gutjahr, Paul C. (2001). "Sacred Texts in the United States". Book History. 4: (335–370) 348. doi:10.1353/bh.2001.0008. JSTOR 30227336. S2CID 162339753.

- ^ "Women and the Law". The Mary Baker Eddy Library. 22 January 2016. Archived from the original on 18 January 2021.

- ^ For the charter, Eddy, Mary Baker (1908) [1895]. Manual of the Mother Church, 89th edition. Boston: The First Church of Christ, Scientist. pp. 17–18.

- ^ Stark 1998, pp. 190–191.

- ^ Fuller 2011, p. 175

- ^ Jump up to: a b Wilson, Bryan (1961). Sects and Society: A Sociological Study of the Elim Tabernacle, Christian Science, and Christadelphians. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 125.

Eddy, Manual of the Mother Church, p. 17.

- ^ Wilson 1961, p. 124.

- ^ Wilson 1961, p. 127; Rescher, Nicholas (2009) [1996]. "Idealism", in Jaegwon Kim, Ernest Sosa (eds.). A Companion to Metaphysics. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 318 Archived 2022-11-01 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Wilson 1961, p. 125.

- ^ Battin, Margaret P. (1999). "High-Risk Religion: Christian Science and the Violation of Informed Consent". In DesAutels, Peggy; Battin, Margaret P.; May, Larry (eds.). Praying for a Cure: When Medical and Religious Practices Conflict. Lanham, MD, and Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 11. ISBN 0-8476-9262-0.

- ^ Schoepflin, Rennie B. (2003). Christian Science on Trial: Religious Healing in America. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 192–193.

Trammell, Mary M., chair, Christian Science board of directors (March 26, 2010). "Letter; What the Christian Science Church Teaches" Archived 2022-08-07 at the Wayback Machine. The New York Times.

- ^ Regarding vaccines specifically, see:

- Christine Pae (September 1, 2021). "Here's who qualifies for a religious exemption to Washington's COVID-19 vaccine mandate". Archived 2021-09-28 at the Wayback Machine. KING 5.

- Samantha Maiden (April 18, 2015). "No Jab, No Pay reforms: Religious exemptions for vaccination dumped". Archived 2021-09-28 at the Wayback Machine. Daily Telegraph (Australia).

- ^ Schoepflin 2003, pp. 212–216 Archived 2022-11-01 at the Wayback Machine; Peters, Shawn Francis (2007). When Prayer Fails: Faith Healing, Children, and the Law. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 91, 109–130. Archived 2022-11-01 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ William G. McLoughlin, Revivals, Awakenings, and Reform, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1980, pp. 10–11, 16–17.

Roy M. Anker, "Revivalism, Religious Experience and the Birth of Mental Healing," Self-help and Popular Religion in Early American Culture: An Interpretive Guide, Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Company, 1999(a), (pp. 11–100), pp. 8, 176ff.

- ^ Hutchinson, Dawn (November 2014). "New Thought's Prosperity Theology and Its Influence on American Ideas of Success", Nova Religio: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions, 18(2), (pp. 28–44), p. 28. JSTOR 10.1525/nr.2014.18.2.28

- ^ Saliba, John (2003). Understanding New Religious Movements. Walnut Creek, CA: Rowman Altamira. p. 26 Archived 2022-11-01 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Lewis, James R. (2003). Legitimating New Religions. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. p. 94 Archived 2022-11-01 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Simmons, John K. (1995). "Christian Science and American Culture", in Timothy Miller (ed.). America's Alternative Religions, New York: State University of New York Press. p. 61 Archived 2022-11-01 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Charles S. Braden, Spirits in Rebellion: The Rise and Development of New Thought, Dallas: Southern Methodist University Press, 1963, pp. 4–5.

- ^ John S. Haller, The History of New Thought: From Mental Healing to Positive Thinking and the Prosperity Gospel, West Chester, PA: Swedenborg Foundation Press, 2012, pp. 10–11.

Horatio W. Dresser, A History of the New Thought Movement, New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Company, 1919, pp. 152–153.

For early uses of New Thought, William Henry Holcombe, Condensed Thoughts about Christian Science (pamphlet), Chicago: Purdy Publishing Company, 1887; Horatio W. Dresser, "The Metaphysical Movement" (from a statement issued by the Metaphysical Club, Boston, 1901), The Spirit of the New Thought, New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Company, 1917, p. 215.

- ^ Simmons 1995, p. 61.

- ^ Dell De Chant, "The American New Thought Movement," in Eugene Gallagher and Michael Ashcraft (eds.), Introduction to New and Alternative Religions in America, Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Company, 2007, pp. 81–82.

- ^ William James, The Varieties of Religious Experience (Gifford Lectures, Edinburgh), New York: Longmans, Green, & Co, 1902, pp. 75–76; "New Thought" Archived 2015-05-16 at the Wayback Machine, Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2014.

- ^ de Chant 2007, p. 73.

- ^ James 1902, p. 94.

- ^ James 1902, p. 106.

- ^ Stark 1998, pp. 197–198, 211–212; de Chant 2007, p. 67.

- ^ Wilson 1961, p. 135 Archived 2022-11-01 at the Wayback Machine; Braden 1963, p. 62 (for "the truth is the cure"); McGuire 1988, p. 79 Archived 2022-11-01 at the Wayback Machine.

Also see "Religion: New Thought" Archived 2014-12-20 at the Wayback Machine, Time magazine, 7 November 1938; "Phineas Parkhurst Quimby" Archived 2014-11-11 at the Wayback Machine, Encyclopædia Britannica, September 9, 2013.

- ^ Philip Jenkins, Mystics and Messiahs: Cults and New Religions in American History, Oxford University Press, 2000, pp. 53–54.

- ^ Simmons 1995, p. 64 Archived 2022-11-01 at the Wayback Machine; Fuller 2013, pp. 212–213 Archived 2022-11-01 at the Wayback Machine, n. 16.

- ^ Wilson 1961, p. 156 Archived 2022-11-01 at the Wayback Machine; Braden 1963, pp. 14, 16; Simmons 1995, p. 61 Archived 2022-11-01 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ McGuire 1988, p. 79.

- ^ Wilson 1961, pp. 126–127 Archived 2022-11-01 at the Wayback Machine; Braden 1963, pp. 18–19.

- ^ Gottschalk, Stephen (1973). The Emergence of Christian Science in American Religious Life. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 128, 148–149.

Moore, Laurence R. (1986). Religious Outsiders and the Making of Americans. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 112–113.

Simmons 1995, p. 62 Archived 2022-11-01 at the Wayback Machine; Whorton, James C. (2004). Nature Cures: The History of Alternative Medicine in America. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 128–129 Archived 2022-11-01 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Craig R. Prentiss, "Sickness, Death and Illusion in Christian Science," in Colleen McDannell (ed.), Religions of the United States in Practice, Vol. 1, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001, p. 322 Archived 2022-11-01 at the Wayback Machine.

Claudia Stokes, The Altar at Home: Sentimental Literature and Nineteenth-Century American Religion, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2014, p. 181 Archived 2022-11-01 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Braden 1963, p. 19; Stark 1998, p. 195

- ^ Anker 1999(a), p. 9 Archived 2022-11-01 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Catherine Albanese, A Republic of Mind and Spirit: A Cultural History of American Metaphysical Religion, New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007, p. 284.

- ^ Wilson 1961, p. 121; Eddy, Manual of the Mother Church, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Eddy, Retrospection and Introspection, The First Church of Christ, Scientist, 1891, p. 70.

- ^ Eddy, Christian Science Journal, January 1901, reprinted in "The Christian Science Textbook," The First Church of Christ, Scientist, and Miscellany, Boston: Alison V. Stewart, 1914, p. 115.

- ^ David L. Weddle, "The Christian Science Textbook: An Analysis of the Religious Authority of Science and Health by Mary Baker Eddy" Archived 2020-07-29 at the Wayback Machine, The Harvard Theological Review, 84(3), 1991, p. 281; Gottschalk 1973, p. xxi.

- ^ Eddy, Manual of the Mother Church, p. 58; Weddle 1991 Archived 2020-07-29 at the Wayback Machine, p. 273.

- ^ J. Gordon Melton, "Church of Christ, Scientist (Christian Science)," Encyclopedic Handbook of Cults in America, New York: Routledge, 1992, p. 36 Archived 2022-11-01 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Stark 1998, p. 195.

- ^ Wilson 1961, p. 122 Archived 2022-11-01 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Wilson 1961, p. 127 Archived 2022-11-01 at the Wayback Machine; Moore 1986, p. 112 Archived 2022-11-01 at the Wayback Machine; Simmons 1995, p. 62 Archived 2022-11-01 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ For personhood, "Father–Mother God" and "she", see Gottschalk 1973, p. 52 Archived 2022-11-01 at the Wayback Machine; for Ann Lee, see Stokes 2014, p. 186 Archived 2022-11-01 at the Wayback Machine. For the seven synonyms, see Wilson 1961, p. 124 Archived 2022-11-01 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Eddy, Science and Health, "Recapitulation" Archived 2014-02-03 at the Wayback Machine, p. 465:

- ^ Wilson 1961, pp. 121 Archived 2022-11-01 at the Wayback Machine, 125.

- ^ Wilson 1961, p. 129; Stark 1998, pp. 196–197

- ^ Wilson 1961, pp. 125–126.

- ^ Wilson 1961, pp. 123, 128–129.

- ^ Wilson 1961, p. 122; Gottschalk 1972, p. xxvii; "Genesis Chapter 2" Archived 2014-11-11 at the Wayback Machine, kingjamesbibleonline.org.

- ^ Eddy, Science and Health, p. 256; Wilson 1961, p. 127.

- ^ Eddy, Retrospection and Introspection, p. 26.

- ^ Wilson 1961, p. 121; Stark 1998, pp. 199

- ^ Wilson 1961, p. 124.

- ^ Gottschalk 1973, p. 95 Archived 2022-11-01 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Melton 1992, p. 36 Archived 2022-11-01 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ J. Gordon Melton, "An Introduction to New Religions," in James R. Lewis (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of New Religious Movements, New York: Oxford University Press, 2003, p. 17; for Barrington, see Jenkins 2000, p. 49.

- ^ Raymond J. Cunningham, "The Impact of Christian Science on the American Churches, 1880–1910" Archived 2017-04-02 at the Wayback Machine, The American Historical Review, 72(3), April 1967 (pp. 885–905), p. 892; "Faith Healing in America," The Times, May 26, 1885.

- ^ Mark Twain, Christian Science, p. 180 Archived 2022-11-01 at the Wayback Machine; "Mark Twain & Mary Baker Eddy, a film by Val Kilmer" Archived 2014-06-28 at the Wayback Machine, YouTube, from 04:30 mins.

- ^ Bates & Dittemore 1932, pp. 3–5; Gill 1998, p. 3.

- ^ Bates & Dittemore 1932, pp. 16–25; Gill 1998, pp. 35–37; Voorhees 2021, pp. 22–24.

- ^ Milmine & Cather 1909, p. 41; Voorhees 2021, pp. 24–26; Melton 1992 p. 29.

- ^ Bates & Dittemore 1932, pp. 30, 36, 40, 50–52; Fraser 1999, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Gill 1998, pp. 100–102, 113–115.

- ^ "Women and the Law". Women, Enterprise & Society. Harvard Business School. Archived from the original on 24 August 2019.

- ^ Voorhees 2021, pp. 30.

- ^ Piepmeier, Alison (2004). Out in public: configurations of women's bodies in nineteenth-century America. University of North Carolina Press. pp. 63, 229; Voorhees 2021, pp. 32–34; Bates & Dittemore 1932, p. 88; Melton 1992, p. 29.

- ^ Gill 1998, pp. 119–121.

- ^ Gill 1998, pp. 161–168; Voorhees 2021, pp. 57–58; Melton 1992, pp. 29–30; Mead, Frank S. (1995) Handbook of Denominations in the United States. Abingdon Press. p. 104.

- ^ Gill 1998, pp. 161–168; Voorhees 2021, pp. 57–58. For her account see: Eddy, "The Great Discovery", Retrospection and Introspection, pp. 24–29.

- ^ Bates & Dittemore 1932, pp. 118–135; Gottschalk 2006, pp. 80–81; Voorhees 2021, pp. 65–70; Gutjahr, Paul C. "Sacred Texts in the United States", Book History, 4, 2001 (335–370), 348. JSTOR 30227336

- ^ Gill 1998, pp. xxxi, xxxiii, 274, 357–358. Milmine, McClure's, August 1907, p. 458.

- ^ Koestler-Grack 2004, p. 52; Milmine, McClure's, September 1907, p. 567; Bates & Dittemore 1932, p. 210; Melton 1992, p. 30.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gill 1998, pp. xxxix–xxxv; Chronology Archived 2022-01-12 at the Wayback Machine, Mary Baker Eddy Library.

- ^ Fuller 2011, p. 1.

- ^ Paul Eli Ivey, Prayers in Stone: Christian Science Architecture in the United States, 1894–1930, Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1999, p. 31; "First Church of Christ, Scientist" Archived 2013-10-29 at the Wayback Machine, Oconto County Historical Society.

- ^ Gill 1998, p. 450; Beasley 1956, pp. 385–386.

- ^ Gill 1998, pp. xxi–xxii, 169–208, 471–520.

- ^ Gill 1998, pp. 453–454.

- ^ Gill 1998, pp. 563–568.

- ^ Bates & Dittemore 1932, pp. 396–417; Gill 1998, pp. 471–520.

- ^ Bates & Dittemore 1932, pp. 411–417; "Dr. Alan McLane Hamilton Tells About His Visit to Mrs. Eddy" Archived 2021-02-24 at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times, August 25, 1907.

- ^ Canham, Erwin (1958). Commitment To Freedom: The Story of the Christian Science Monitor. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. pp. 14–15.

- ^ Bates & Dittemore 1932, p. 451; "New York Eddyites Take Death Calmly" Archived 2021-02-26 at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times, December 5, 1910; "Look for Mrs. Eddy to rise from tomb" Archived 2021-01-10 at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times, December 29, 1910.

- ^ "Nothing left to relatives" Archived 2021-02-25 at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times, December 8, 1910; "Church gets most of her estate" Archived 2021-01-10 at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times, December 15, 1910.

- ^ Gill 1998, p. 119.

- ^ Wilson 1961, pp. 135–136, n. 3; Braden 1967, p. 296; Gardner 1993, pp. 145–154. Also see Bryan Wilson, "The Origins of Christian Science: A Survey," Hibbert Journal, January 1959.

- ^ Bates and Dittemore 1932, pp. 248–249.

- ^ Gardner 1993, pp. 145–154; for rebuttal, Thomas C. Johnsen, "Historical Consensus and Christian Science: The Career of a Manuscript Controversy", The New England Quarterly, 53(1), March 1980, pp. 3–22.

- ^ Braden 1967, p. 296; Blair, "The Man of Integrity," in Lindley Murray, The English Reader, York: Longman and Rees, 1799, p. 151; Eddy, Miscellaneous Writings 1883–1896, Boston: Joseph Armstrong, 1897, p. 147.

- ^ Peel 1966, p. 259; Bates and Dittemore 1932, pp. 142–143.

- ^ Eddy, Miscellaneous Writings, 1883–1896, Boston: Joseph Armstrong, 1897, p. 62.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "A. O." "The Founder of the Mental Method of Treating Disease," Boston Post, February 8, 1883; "E. G."'s reply, February 19, 1883 (in Septimus J. Hanna, Christian Science History, Boston: The Christian Science Publishing Company, 1899, p. 26ff).

Dresser's reply, February 23, 1883; Eddy's reply, March 7, 1883, in Dresser 1919, p. 58.

Also see Horatio Dresser (ed.), The Quimby Manuscripts, New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Company, 1921, p. 433; Bates & Dittemore 1932, pp. 233–238; Peel 1971, p. 130.

- ^ Peel 1971, pp. 135–136, citing Eddy, Journal of Christian Science, December 1883.

- ^ Bates & Dittemore 1932, pp. 211–212, 240–242.

- ^ Bates & Dittemore 1932, pp. 240–242; Peel 1971, pp. 133–134, 344, n. 44, for Quimby's son sending the manuscript overseas); also see Gill 1998, p. 316.

- ^ Ventimiglia, Andrew (2019). Copyrighting God: Ownership of the Sacred in American Religion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 119–122. ISBN 978-1-108-42051-8.

- ^ Bates & Dittemore 1932, pp. 243–244; Julius A. Dresser, The True History of Mental Science, Boston: Alfred Mudge & Son, 1887.

There was also an article, George A. Quimby, "Phineas Parkhurst Quimby", The New England Magazine, 6(33), March 1888, pp. 267–276.

- ^ Bates and Dittemore 1932, pp. 129–130.

- ^ Bates and Dittemore 1932, p. 241.

- ^ Eddy, "Reminiscences," The First Church of Christ, Scientist, and Miscellany, pp. 306–307.

- ^ Eddy, Science and Health, 1889, p. 7.

- ^ Eddy, Retrospection and Introspection, p. 35.

- ^ Eddy, Retrospection and Introspection, p. 36.

- ^ Lyman Pierson Powell, Christian Science: The Faith and Its Founder, New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1917 [1907], p. 71.

- ^ "True Origin of Christian Science", The New York Times, July 10, 1904.

- ^ Also see Quimby, "Questions and Answers", The Quimby Manuscripts, chapter 13; Cather and Milmine 1909, pp. 125–133.

For more on the manuscripts, S. P. Bancroft, Mrs. Eddy as I Knew Her in 1870 (1923); for the history of the Science and Man manuscript, Peel 1966, pp. 231–236, and Fraser 1999, p. 468, n. 99. Several versions of Science and Man can be found in "Essays and other footprints left by Mary Baker Eddy", Rare Book Company, Freehold, New Jersey, p. 178ff. - ^ Bates and Dittemore 1932, pp. 156, 244–245.

- ^ Peel 1966, pp. 179–183, particularly 182; Peel 1971, p. 345, n. 44.

- ^ Gardner 1993, p. 47; Gill 1998, p. 316.

- ^ Cather and Milmine 1909, p. 355; for Eddy calling herself "Professor of Obstetrics," Gill 1998, p. 347; for two one-week classes, Peel 1971, p. 237.

- ^ Schoepflin 2003, p. 212.

- ^ Cather and Milmine 1909, pp. 354–355; Bates and Dittemore 1932, p. 282; Peel 1971, p. 237; Schoepflin 2003, pp. 82–85.

"Christian Science Killed Her", The New York Times, May 18, 1888; "Mrs. Corner on Trial", May 22, 1888; "The Christian Scientist Held", May 26, 1888; "The Christian Scientist Not Indicted", June 10, 1888.

- ^ Cather and Milmine 1909, p. 356; for the secretary resigning, Bates and Dittemore 1932, p. 283.

- ^ Schoepflin 2003, pp. 212–217.

- ^ Cunningham 1967, p. 902; Peters 2007, p. 98.

- ^ Schoepflin 2003, p. 189; Peters 2007, p. 100.

- ^ Peters 2007, pp. 107–108.

- ^ Michael Willrich, Pox: An American History, Penguin Press, 2011, pp. 260–261.

- ^ "Christian Scientists' change of front", The New York Times, November 14, 1902; Peters 2007, pp. 94–95;

- ^ Beasley 1956, p. 3.

- ^ Stark 1998;[page needed] Beasley 1956, p. 80.

- ^ Eddy, "Discipline" Archived 2013-07-24 at the Wayback Machine, Manual of the Mother Church, Article VIII, Section 28.

- ^ Stark 1998, pp. 190–191; Dart, John (20 December 1986). "Healing Church Shows Signs It May Be Ailing" Archived 2015-09-28 at the Wayback Machine, Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Stores, Bruce (2004). Christian Science: Its Encounter with Lesbian/Gay America. iUniverse. p. 34

- ^ Christian Science practitioner figures, and practitioners per million, 1883–1995: Stark 1998, p. 192, citing the Christian Science Journal.

- ^ Melton 1992, p. 34.

- ^ Melton 1992, pp. 34–37.

- ^ Melton 1992, p. 34; Beasley 1956, pp. 46–77, 81.

- ^ Simmons, John K. (1991). When Prophets Die: The Postcharismatic Fate of New Religious Movements. Albany: State University of New York Press. pp. 113–115; Beasley 1956, pp. 144–181; The "Great Litigation" Archived 2022-01-13 at the Wayback Machine. Mary Baker Eddy Library. March 30, 2012.

- ^ King, Christine Elizabeth. (1982). The Nazi State and The New Religions: Five Case Studies in Non-Conformity. Lewiston, New York: Edwin Mellen Press. pp. 29–57; Beasley 1956, pp. 233–246; Sandford, Gregory W. (2014). Christian Science in East Germany: The Church that Came in from the Cold. CreateSpace Independent Publishing.

- ^ Beasley 1956, pp. 245–246; Abiko, Emi (1978). A Precious Legacy: Christian Science Comes to Japan. E. D. Abbott Co.

- ^ Barns, Linda L.; Plotnikoff, Gregory A.; Fox, Kenneth; Pendleton, Sara (2000). "Spirituality, Religion, and Pediatrics: Intersecting Worlds of Healing". Pediatrics 104, no. 6: 899–911; DesAutels, Peggy; Battin, Margaret; May, Larry (1999). Praying for a Cure: When Medical and Religious Practices Conflict. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers; Kondos, Elena M. (1992). "The Law and Christian Science Healing for Children: A Pathfinder." Legal Reference Services Quarterly. 12: 5–71; Gill 1998, pp. xv–xvi.

- ^ "Court rejects Christian Science motion on bequests" Archived 2021-12-07 at the Wayback Machine Stanford University. Press release, September 23, 1992; "Christian Scientists Charge Their Church with Violating Its Principles" Archived 2022-01-12 at the Wayback Machine Christian Research Institute, April 9, 2009; "Christian Science Church Settles Claim to Bequest" Archived 2022-01-12 at the Wayback Machine The New York Times, October 14, 1993.

- ^ Bridge, Susan (1998). Monitoring the News: The Brilliant Launch and Sudden Collapse of the Monitor Channel. Armonk, New York: M.E. Sharpe; Gold, Allan R. (November 15, 1988). "Editors of Monitor Resign Over Cuts" Archived 2022-01-12 at the Wayback Machine. The New York Times.

- ^ Christian Science Board of Directors (October 2023). "A message from the Christian Science Board of Directors". The Christian Science Journal. 141 (10). Retrieved 1 July 2024.

- ^ Knee 1994, pp. 62, 134–135; Melton 1992, pp. 4, 34–37.

- ^ Melton, J. Gordon (1999). Encyclopedia of American religions. Detroit: Gale Research. pp. 140–142.

- ^ Christian Science Journal Directory Search Archived 2022-01-12 at the Wayback Machine. christianscience.com

- ^ Christa Case Bryant (June 9, 2009). "Africa contributes biggest share of new members to Christian Science church" Archived 2012-12-25 at the Wayback Machine. The Christian Science Monitor.

- ^ Fraser 1999, p. 563.

- ^ Fuller 2011, pp. 1–8; Squires, L. Ashley (2015). "All the News Worth Reading: The Christian Science Monitor and the Professionalization of Journalism" Archived 2022-01-12 at the Wayback Machine. Book History. 18: 235–272.

- ^ Frank Prinz-Wondollek, "How does Christian Science heal?" Archived 2015-05-23 at the Wayback Machine, Boston: Christian Science Lectures, April 28, 2011, from 00:02 mins.

- ^ Battin 1999, p. 7 Archived 2022-11-01 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Stark 1998, pp. 196–197; Gottschalk 2006, p. 86 Archived 2022-11-01 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Fraser 1999, pp. 94–96.

- ^ "Teachers and practitioners" Archived 2022-07-06 at the Wayback Machine, Christian Science Journal.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Vitello, Paul (March 23, 2010). "Christian Science Church Seeks Truce With Modern Medicine" Archived 2017-04-02 at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times.

- ^ Fraser 1999, pp. 91–93; Eddy, "Recapitulation" Archived 2014-02-03 at the Wayback Machine, Science and Health.

- ^ Fraser 1999, p. 91.

- ^ Fraser 1999, p. 329; "Christian Science nursing facilities" Archived 2012-09-17 at the Wayback Machine, Commission for Accreditation of Christian Science Nursing Organizations/Facilities.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Battin 1999, p. 15 Archived 2022-11-01 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Testimony Guidelines" Archived 2014-02-19 at the Wayback Machine, JSH-Online, Christian Science church.

- ^ Battin 1999, p. 15 Archived 2022-11-01 at the Wayback Machine; "An Empirical Analysis of Medical Evidence in Christian Science Testimonies of Healing, 1969–1988" Archived 2010-07-10 at the Wayback Machine, Christian Science church, April 1989, pp. 2, 7, courtesy of the Johnson Fund.

- ^ Peters 2007, p. 22; "An Analysis of a Christian Science Study of the Healings of 640 Childhood Illnesses" Archived 2017-04-02 at the Wayback Machine, Death by Religious Exemption, Coalition to Repeal Exemptions to Child Abuse Laws, Massachusetts Committee for Children and Youth, January 1992, Section IX, p. 34.

- ^ Talbot, Nathan (1983). "The position of the Christian Science church". New England Journal of Medicine. 309 (26): 1641–1644 [1642]. doi:10.1056/NEJM198312293092611. PMID 6646189.

- ^ Samantha Maiden (April 18, 2015). "No Jab, No Pay reforms: Religious exemptions for vaccination dumped" Archived 2021-09-28 at the Wayback Machine. Daily Telegraph.

- ^ Christine Pae (September 1, 2021). "Here's who qualifies for a religious exemption to Washington's COVID-19 vaccine mandate" Archived 2021-09-28 at the Wayback Machine. KING 5.

- ^ Stark 1998, p. 193.

- ^ Eddy, "List of Church Officers" Archived 2014-03-22 at archive.today, Manual of the Mother Church; Gottschalk 1973, p. 190; Fraser (Atlantic) 1995 Archived 2017-02-11 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Steve Stecklow, "Church's Media Moves At Issue A Burgeoning Network Sparks Dissent" Archived 2013-01-14 at the Wayback Machine, Philadelphia Inquirer, October 14, 1991;[failed verification] Fraser 1999, pp. 373–374[better source needed]

- ^ Boston Landmarks Commission 2011 Archived 2015-09-23 at the Wayback Machine, p. 1.

- ^ Boston Landmarks Commission 2011 Archived 2015-09-23 at the Wayback Machine, pp. 5–6.

- ^ "Christian Science Plaza Revitalization Project Citizen Advisory Committee (CAC)" Archived 2015-07-01 at the Wayback Machine, Boston Redevelopment Authority.

- ^ Boston Landmarks Commission 2011 Archived 2015-09-23 at the Wayback Machine, p. 18.

- ^ Eddy, Manual of the Mother Church Archived 2013-08-19 at the Wayback Machine, 89th edition.

- ^ Gottshalk 1973, p. 183.

- ^ Eddy, "Discipline" Archived 2013-07-24 at the Wayback Machine, Manual of the Mother Church, Article VIII, Section 4; for more about prayer, Gottschalk 1973, pp. 239–240.

- ^ Eddy, "Discipline" Archived 2013-07-24 at the Wayback Machine, Manual of the Mother Church, Article VIII, Sections 13, 14.

- ^ Eddy, "Discipline" Archived 2013-07-24 at the Wayback Machine, Manual of the Mother Church, Article VIII, Sections 8, 12, 17, 26, 28.

- ^ Eddy, "Discipline" Archived 2013-07-24 at the Wayback Machine, Manual of the Mother Church, Article X, Section 1.

- ^ Eddy, "Discipline" Archived 2013-07-24 at the Wayback Machine, Manual of the Mother Church, Article XI, Section 9.

- ^ Eddy, "Discipline" Archived 2013-07-24 at the Wayback Machine, Manual of the Mother Church, Article VIII, Section 27.

- ^ Stuart M. Matlins; Arthur J. Magida, How to Be a Perfect Stranger: The Essential Religious Etiquette Handbook, Skylight Paths Publishing, 2003 (pp. 70–76)Dell de Chant, "World Religions made in the U.S.A.: Metaphysical Communities – Christian Science and Theosophy," in Jacob Neusner (ed.), World Religions in America, Westminster John Knox Press, 2009 (pp. 251–270), p. 257.

"Sunday church services and Wednesday testimony meetings" Archived 2014-02-09 at the Wayback Machine, and "Online Wednesday meetings" Archived 2020-06-13 at the Wayback Machine, First Church of Christ, Scientist.