John A. Macdonald

John A. Macdonald | |

|---|---|

Macdonald, c. 1875 | |

| 1st Prime Minister of Canada | |

| In office 17 October 1878 – 6 June 1891 | |

| Monarch | Victoria |

| Governors General | |

| Preceded by | Alexander Mackenzie |

| Succeeded by | John Abbott |

| In office 1 July 1867 – 5 November 1873 | |

| Monarch | Victoria |

| Governors General |

|

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Alexander Mackenzie |

| Leader of the Conservative Party | |

| In office 1 July 1867 – 6 June 1891 | |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | John Abbott |

| Member of the House of Commons of Canada | |

| In office 1867 – 6 June 1891 | |

| Joint-Premier of the Province of Canada | |

| In office 30 May 1864 – 30 June 1867 | |

| Monarch | Victoria |

| Preceded by | John Sandfield Macdonald |

| Succeeded by | Position abolished |

| In office 6 August 1858 – 24 May 1862 | |

| Monarch | Victoria |

| Preceded by | George Brown |

| Succeeded by | John Sandfield Macdonald |

| In office 24 May 1856 – 2 August 1858 | |

| Monarch | Victoria |

| Preceded by | Allan MacNab |

| Succeeded by | George Brown |

| Personal details | |

| Born | John Alexander Mcdonald[a] 10 or 11 January 1815[b] Glasgow, Scotland |

| Died | June 6, 1891 (aged 76) Ottawa, Ontario, Canada |

| Resting place | Cataraqui Cemetery |

| Political party | Conservative |

| Other political affiliations |

|

| Spouses | |

| Children | 3, including Hugh John Macdonald |

| Education | Apprenticeship |

| Profession |

|

| Signature | |

| Nicknames |

|

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | Province of Upper Canada |

| Branch/service | Loyalist militia |

| Years of service | 1837-1838 |

| Rank | Private Ensign |

| Unit | Commercial Bank Guard 3rd Frontenac Militia Regiment |

| Battles/wars | Upper Canada Rebellion |

Cabinet offices held

Leadership offices held

Parliamentary offices held

| |

| This article is part of a series on |

| Conservatism in Canada |

|---|

|

Sir John Alexander Macdonald[a] GCB PC QC ( 10 or 11 January 1815[b] – 6 June 1891) was the first prime minister of Canada, serving from 1867 to 1873 and from 1878 until his death in 1891. He was the dominant figure of Canadian Confederation, and had a political career that spanned almost half a century.

Macdonald was born in Scotland; when he was a boy his family immigrated to Kingston in the Province of Upper Canada (today in eastern Ontario). As a lawyer, he was involved in several high-profile cases and quickly became prominent in Kingston, which elected him in 1844 to the legislature of the Province of Canada. By 1857, he had become premier under the colony's unstable political system. In 1864, when no party proved capable of governing for long, Macdonald agreed to a proposal from his political rival, George Brown, that the parties unite in a Great Coalition to seek federation and political reform. Macdonald was the leading figure in the subsequent discussions and conferences, which resulted in the British North America Act and the establishment of Canada as a nation on 1 July 1867.

Macdonald was the first prime minister of the new nation, and served 19 years; only William Lyon Mackenzie King has served longer. In his first term, Macdonald established the North-West Mounted Police and expanded Canada by annexing the North-Western Territory, Rupert's Land, British Columbia, and Prince Edward Island. In 1873, he resigned from office over a scandal in which his party took bribes from businessmen seeking the contract to build the Canadian Pacific Railway. However, he was re-elected in 1878. Macdonald's greatest achievements were building and guiding a successful national government for the new Dominion, using patronage to forge a strong Conservative Party, promoting the protective tariff of the National Policy, and completing the railway. He fought to block provincial efforts to take power back from the national government in Ottawa. He approved the execution of Métis leader Louis Riel for treason in 1885 which alienated many francophones from his Conservative Party. He continued as prime minister until his death in 1891. He remains the oldest prime minister in Canadian history.

In the 21st century, Macdonald has come under criticism for his role in the Chinese Head Tax and federal policies towards Indigenous peoples, including his actions during the North-West Rebellion that resulted in Riel's execution, and the development of the residential school system designed to assimilate Indigenous children. Macdonald, however, remains respected for his key role in the formation of Canada. Historical rankings in surveys of experts in Canadian political history have consistently placed Macdonald as one of the highest-rated prime ministers in Canadian history.

Early years, 1815–1830

John Alexander Macdonald was born[a] in Ramshorn parish in Glasgow, Scotland, on 10 January (official record) or 11 (father's journal) 1815.[b][1] His father Hugh, an unsuccessful merchant, had married John's mother, Helen Shaw, on 21 October 1811.[2] John Alexander Macdonald was the third of five children. After Hugh's business ventures left him in debt, the family immigrated to Kingston, in Upper Canada (today the southern and eastern portions of Ontario), in 1820, as the family had several relatives and connections there.[3]

The family initially lived together, then resided over a store which Hugh Macdonald ran. Soon after their arrival, John's younger brother James died from a blow to the head by a servant charged with taking care of the boys. After Hugh's store failed, the family moved to Hay Bay (south of Napanee, Ontario), west of Kingston, where Hugh unsuccessfully ran another shop. In 1829, his father was appointed as a magistrate for the Midland District.[4] John Macdonald's mother was a lifelong influence on her son, helping him in his difficult first marriage and remaining influential in his life until her 1862 death.[5]

Macdonald initially attended local schools. When he was aged 10, his family gathered enough money to send him to Midland District Grammar School in Kingston.[5] Macdonald's formal schooling ended at 15, a common school-leaving age at a time when only children from the most prosperous families were able to attend university.[6] Macdonald later regretted leaving school when he did, remarking to his secretary Joseph Pope that if he had attended university, he might have embarked on a literary career.[7]

Legal career, 1830–1843

Legal training and early career, 1830–1837

Macdonald's parents decided he should become a lawyer after leaving school.[8] As Donald Creighton (who penned a two-volume biography of Macdonald in the 1950s) wrote, "law was a broad, well-trodden path to comfort, influence, even to power".[9] It was also "the obvious choice for a boy who seemed as attracted to study as he was uninterested in trade."[9] Macdonald needed to start earning money immediately to support his family because his father's businesses were failing. "I had no boyhood," he complained many years later. "From the age of 15, I began to earn my own living."[10]

Macdonald travelled by steamboat to Toronto (known until 1834 as York), where he passed an examination set by The Law Society of Upper Canada. British North America had no law schools in 1830; students were examined when beginning and ending their tutelage. Between the two examinations, they were apprenticed, or articled to established lawyers.[11] Macdonald began his apprenticeship with George Mackenzie, a prominent young lawyer who was a well-regarded member of Kingston's rising Scottish community. Mackenzie practised corporate law, a lucrative speciality that Macdonald himself would later pursue.[12] Macdonald was a promising student, and in the summer of 1833, managed the Mackenzie office when his employer went on a business trip to Montreal and Quebec in Lower Canada (today the southern portion of the province of Quebec). Later that year, Macdonald was sent to manage the law office of a Mackenzie cousin who had fallen ill.[13]

In August 1834, George Mackenzie died of cholera. With his supervising lawyer dead, Macdonald remained at the cousin's law office in Hallowell (today Picton, Ontario). In 1835, Macdonald returned to Kingston, and even though not yet of age nor qualified, began his practice as a lawyer, hoping to gain his former employer's clients.[14] Macdonald's parents and sisters also returned to Kingston.[15]

Soon after Macdonald was called to the Bar in February 1836, he arranged to take in two students; both became, like Macdonald, Fathers of Confederation. Oliver Mowat became premier of Ontario, and Alexander Campbell a federal cabinet minister and Lieutenant Governor of Ontario.[8] One early client was Eliza Grimason, an Irish immigrant then aged sixteen, who sought advice concerning a shop she and her husband wanted to buy. Grimason would become one of Macdonald's richest and most loyal supporters, and may have also become his lover.[16] Macdonald joined many local organisations, seeking to become well known in the town. He also sought out high-profile cases, representing accused child rapist William Brass. Brass was hanged for his crime, but Macdonald attracted positive press comments for the quality of his defence.[17] According to one of his biographers, Richard Gwyn:

As a criminal lawyer who took on dramatic cases, Macdonald got himself noticed well beyond the narrow confines of the Kingston business community. He was operating now in the arena where he would spend by far the greatest part of his life – the court of public opinion. And, while there, he was learning the arts of argument and of persuasion that would serve him all his political life.[18]

Military service

All male Upper Canadians between 18 and 60 years of age were members of the Sedentary Militia, which was called into active duty during the Rebellions of 1837. Macdonald served as a Private in Captain George Well's Company of the Commercial Bank Guard.[19]

Macdonald and the militia marched to Toronto to confront the rebels, and Sir Joseph Pope, Macdonald's private secretary, recalled Macdonald's account of his experience during the march:

"I carried my musket in '37", he was wont to say in after years. One day he gave me an account of a long march his company made, I forget from what place, but Toronto was the objective point: "The day was hot, my feet were blistered – I was but a weary boy – and I thought I should have dropped under the weight of the old flint musket which galled my shoulder. But I managed to keep up with my companion, a grim old soldier who seemed impervious to fatigue."[20]

The Bank Guard served on active duty in Toronto guarding the Commercial Bank of the Midland District on King Street. The company was present at the Battle of Montgomery's Tavern and Macdonald recalled in an 1887 letter to Sir James Gowan that:[21]

"I was in the Second or Third Company behind the cannon that opened out on Montgomery’s House. During the week of the rebellion I was [in] the Commercial Bank Guard in the house on King Street, afterward the habitat of George Brown’s 'Globe'."[22]

The Bank Guard was taken off active service on 17 December 1837, and returned to Kingston.[23]

On 15 February 1838, Macdonald was appointed an Ensign in the 3rd (East) Regiment of Frontenac Militia[21] but did not take up the position, serving briefly as a Private in the regiment, patrolling the area around Kingston.[24] The town saw no real action during 1838 and Macdonald was not called upon to fire on the enemy,[25] however the Frontenac Militia regiments were on active duty in Kingston while the Battle of the Windmill occurred.[26]

Professional prominence, 1837–1843

Although most of the trials resulting from the Upper Canada Rebellion took place in Toronto, Macdonald represented one of the defendants in the one trial to take place in Kingston. All the Kingston defendants were acquitted, and a local paper described Macdonald as "one of the youngest barristers in the Province [who] is rapidly rising in his profession".[27]

In late 1838, Macdonald agreed to advise one of a group of American raiders who had crossed the border to overthrow British rule in Canada. The raiders had been captured by government forces after the Battle of the Windmill near Prescott, Upper Canada. Public opinion was inflamed against the prisoners, as they were accused of mutilating the body of a dead Canadian lieutenant. Macdonald could not represent the prisoners, as they were tried by court-martial and civilian counsel had no standing. At the request of Kingston relatives of Daniel George, paymaster of the ill-fated invasion, Macdonald agreed to advise George, who, like the other prisoners, had to conduct his own defence.[28] George was convicted and hanged.[29] According to Macdonald biographer Donald Swainson, "By 1838, Macdonald's position was secure. He was a public figure, a popular young man, and a senior lawyer."[30]

Macdonald continued to expand his practice while being appointed director of many companies, mainly in Kingston. He became both a director of and a lawyer for the new Commercial Bank of the Midland District. Throughout the 1840s, Macdonald invested heavily in real estate, including commercial properties in downtown Toronto.[31] Meanwhile, he was suffering from some illness, and in 1841, his father died. Sick and grieving, he decided to take a lengthy holiday in Britain in early 1842. He left for the journey well supplied with money, as he spent the last three days before his departure gambling at the card game loo and winning substantially.[32] Sometime during his two months in Britain, he met his first cousin, Isabella Clark. As Macdonald did not mention her in his letters home, the circumstances of their meeting are not known.[33] In late 1842, Isabella journeyed to Kingston to visit with a sister.[34] The visit stretched for nearly a year before John and Isabella Macdonald married on 1 September 1843.[35]

Political rise, 1843–1864

Parliamentary advancement, 1843–1857

On 29 March 1843, Macdonald was elected as alderman in Kingston's Fourth Ward, with 156 votes against 43 for his opponent, Colonel Jackson. He also suffered what he termed his first downfall, as his supporters, carrying the victorious candidate, accidentally dropped him onto a slushy street.[36][35]

The British Parliament had merged Upper and Lower Canada into the Province of Canada in 1841. Kingston became the initial capital of the new province; Upper Canada and Lower Canada became known as Canada West and Canada East.[37] In March 1844, Macdonald was asked by local businessmen to stand as Conservative candidate for Kingston in the upcoming legislative election.[38] Macdonald followed the contemporary custom of supplying the voters with large quantities of alcohol.[39] Votes were publicly declared in this election, and Macdonald defeated his opponent, Anthony Manahan, by 275 "shouts" to 42 when the election concluded on 15 October 1844.[40] Macdonald was never an orator, and especially disliked the bombastic addresses of the time. Instead, he found a niche in becoming an expert on election law and parliamentary procedure.[41]

In 1844, Isabella fell ill. She recovered, but the illness recurred the following year, and she became an invalid. John took his wife to Savannah, Georgia, in the United States in 1845, hoping that the sea air and warmth would cure her ailments. John returned to Canada after six months and Isabella remained in the United States for three years.[42] He visited her again in New York at the end of 1846 and returned several months later when she informed him she was pregnant.[43] In August 1847 their son John Alexander Macdonald Jr. was born in New York, but as Isabella remained ill, relatives cared for the infant.[44]

Although he was often absent due to his wife's illness, Macdonald was able to gain professional and political advancement. In 1846, he was made a Queen's Counsel. The same year, he was offered the non-cabinet post of solicitor general, but declined it. In 1847, Macdonald became receiver general.[45] Accepting the government post required Macdonald to give up his law firm income[46] and spend most of his time in Montreal, away from Isabella.[45] When elections were held in December 1848 and January 1849, Macdonald was easily reelected for Kingston, but the Conservatives lost seats and were forced to resign when the legislature reconvened in March 1848. Macdonald returned to Kingston when the legislature was not sitting, and Isabella joined him there in June.[45] In August, their child died suddenly.[47] In March 1850, Isabella Macdonald gave birth to another boy, Hugh John Macdonald, and his father wrote, "We have got Johnny back again, almost his image."[48] Macdonald began to drink heavily around this time, both in public and in private, which Patricia Phenix, who studied Macdonald's private life, attributes to his family troubles.[49]

The Liberals, or Grits, maintained power in the 1851 election but were soon divided by a parliamentary scandal. In September, the government resigned, and a coalition government uniting parties from both parts of the province under Allan MacNab took power. Macdonald did much of the work of putting the government together and served as attorney general. The coalition, which came to power in 1854, became known as the Liberal-Conservatives (referred to, for short, as the Conservatives). In 1855, George-Étienne Cartier of Canada East (today Quebec) joined the Cabinet. Until Cartier's 1873 death, he would be Macdonald's political partner. In 1856, MacNab was eased out as premier by Macdonald, who became the leader of the Canada West Conservatives.[50] Macdonald remained as attorney general when Étienne-Paschal Taché became premier.[51]

Colonial leader, 1858–1864

In July 1857, Macdonald departed for Britain to promote Canadian government projects.[52] On his return to Canada, he was appointed premier in place of the retiring Taché, just in time to lead the Conservatives in a general election.[53] Macdonald was elected in Kingston by 1,189 votes to 9 for John Shaw; other Conservatives, however, did badly in Canada West, and only French-Canadian support kept Macdonald in power.[54] On 28 December, Isabella Macdonald died, leaving John a widower with a seven-year-old son. Hugh John Macdonald would be principally raised by his paternal aunt and her husband.[55]

The Assembly had voted to move the seat of government permanently to Quebec City. Macdonald opposed this and used his power to force the Assembly to reconsider in 1857. Macdonald proposed that Queen Victoria decide which city should be Canada's capital. Opponents, especially from Canada East, argued that the Queen would not make the decision in isolation; she would be bound to receive informal advice from her Canadian ministers. Macdonald's scheme was adopted, with Canada East support assured by allowing Quebec City to serve a three-year term as the seat of government before the Assembly moved to the permanent capital. Macdonald privately asked the Colonial Office to ensure that the Queen would not respond for at least 10 months, or until after the general election.[56] In February 1858, the Queen's choice was announced, much to the dismay of many legislators from both parts of the province: the isolated Canada West town of Ottawa became the capital.[57]

On 28 July 1858, an opposition Canada East member proposed an address to the Queen informing her that Ottawa was an unsuitable place for a national capital. Macdonald's Canada East party members crossed the floor to vote for the address, and the government was defeated. Macdonald resigned, and the Governor General, Sir Edmund Walker Head, invited opposition leader George Brown to form a government. Under the law at that time, Brown and his ministers lost their seats in the Assembly by accepting their positions, and had to face by-elections. This gave Macdonald a majority pending the by-elections, and he promptly defeated the government. Head refused Brown's request for a dissolution of the Assembly, and Brown and his ministers resigned. Head then asked Macdonald to form a government. The law allowed anyone who had held a ministerial position within the last thirty days to accept a new position without needing to face a by-election; Macdonald and his ministers accepted new positions, then completed what was dubbed the "Double Shuffle" by returning to their old posts.[58] In an effort to give the appearance of fairness, Head insisted that Cartier be the titular premier, with Macdonald as his deputy.[59]

In the late 1850s and early 1860s, Canada enjoyed a period of great prosperity, while the railroad and telegraph improved communications. According to Macdonald biographer Richard Gwyn, "In short, Canadians began to become a single community."[60] At the same time, the provincial government became increasingly difficult to manage. An act affecting both Canada East and Canada West required a "double majority" – a majority of legislators from each of the two sections of the province. This led to increasing deadlock in the Assembly.[61] The two sections each elected 65 legislators, even though Canada West had a larger population. One of Brown's major demands was representation by population, which would lead to Canada West having more seats; this was bitterly opposed by Canada East.[62]

The American Civil War led to fears in Canada and in Britain that once the U.S. had concluded its internal warfare, they would invade Canada again.[63] Canada was sometimes a safe haven for Confederate Secret Service operations against the U.S.; many Canadian citizens and politicians were sympathetic to the Confederacy. This led to events such as the Chesapeake Affair, the St. Albans Raid, and a failed attempt to burn down New York City.[64][65][66] As attorney general of Canada West, Macdonald refused to prosecute Confederate operatives who were using Canada to launch attacks on U.S. soil across the border.[67]

With Canadians fearing invasion from the U.S., the British asked that Canadians pay a part of the expense of defence, and a Militia Bill was introduced in the Assembly in 1862. The opposition objected to the expense, and Canada East representatives feared that French-Canadians would have to fight in a war they wanted no part in. Macdonald was drinking heavily and failed to provide much leadership on behalf of the bill. The government fell over the bill, and the Grits took over under the leadership of John Sandfield Macdonald (no relation to John A. Macdonald).[63] The parties held an almost equal number of seats, with a handful of independents able to destroy any government. The new government fell in May 1863, but Head allowed a new election, which did little to change party standings. In December 1863, Canada West MP Albert Norton Richards accepted the post of solicitor general, and so had to face a by-election. John A. Macdonald campaigned against Richards personally, and Richards was defeated by a Conservative. The switch in seats cost the Grits their majority, and they resigned in March. John A. Macdonald returned to office with Taché as titular premier. The Taché-Macdonald government was defeated in June. The parties were deadlocked to such an extent that, according to Swainson, "It was clear to everybody that the constitution of the Province of Canada was dead".[68]

Confederation of Canada, 1864–1867

As his government had fallen again, Macdonald approached the new governor general, Lord Monck, to dissolve the legislature. Before Macdonald could act on this, Brown approached him through intermediaries; the Grit leader believed that the crisis gave the parties the opportunity to join together for constitutional reform. Brown had led a parliamentary committee on confederation among the British North American colonies, which had reported back just before the Taché-Macdonald government fell.[69] Brown was more interested in representation by population; Macdonald's priority was a federation that the other colonies could join. The two compromised and agreed that the new government would support the "federative principle" – a conveniently elastic phrase. The discussions were not public knowledge and Macdonald stunned the Assembly by announcing that the dissolution was being postponed because of progress in negotiations with Brown – the two men were not only political rivals, but were known to hate each other.[70]

The parties resolved their differences, joining in the Great Coalition, with only the Parti rouge of Canada East, led by Jean-Baptiste-Éric Dorion, remaining apart. A conference, called by the Colonial Office, was scheduled for 1 September 1864, in Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island; the Maritimes were to consider a union. The Canadians obtained permission to send a delegation – led by Macdonald, Cartier, and Brown – to what became known as the Charlottetown Conference. At its conclusion, the Maritime delegations expressed a willingness to join a confederation if the details could be successfully negotiated.[71]

In October 1864, delegates for Confederation met in Quebec City for the Quebec Conference, where they agreed to the Seventy-Two Resolutions, the basis of Canada's government.[72] The Great Coalition was endangered by Taché's 1865 death; Lord Monck asked Macdonald to become premier, but Brown felt that he had as good a claim on the position as his coalition partner. The disagreement was resolved by appointing another compromise candidate to serve as titular premier, Narcisse-Fortunat Belleau.[73]

In 1865, after lengthy debates, Canada's legislative assembly approved confederation by 91 votes to 33.[74] None of the Maritimes, however, had approved the plan. In 1866, Macdonald and his colleagues financed pro-confederation candidates in the New Brunswick general election, resulting in a pro-confederation assembly. Shortly after the election, Nova Scotia's premier, Charles Tupper, pushed a pro-confederation resolution through that colony's legislature.[75] A final conference, to be held in London, was needed before the British Parliament could formalise the union. Maritime delegates left for London in July 1866, but Macdonald, who was drinking heavily again, did not leave until November, angering the Maritimers.[76] In December 1866, Macdonald both led the London Conference, winning acclaim for his handling of the discussions, and courted and married his second wife, Agnes Bernard.[77] Bernard was the sister of Macdonald's private secretary, Hewitt Bernard; the couple first met in Quebec in 1860, but Macdonald had seen and admired her as early as 1856.[78] In January 1867, while still in London, he was seriously burned in his hotel room when his candle set fire to the chair he had fallen asleep in, but Macdonald refused to miss any sessions of the conference. In February, he married Agnes at St George's, Hanover Square.[79] On 8 March, the British North America Act, 1867, which would thereafter serve as the major part of Canada's constitution, passed the House of Commons (it had previously passed the House of Lords).[80] Queen Victoria gave the bill Royal Assent on 29 March 1867.[81]

Macdonald had favoured the union coming into force on 15 July, fearing that the preparations would not be completed any earlier. The British favoured an earlier date and, on 22 May, it was announced that Canada would come into existence on 1 July.[82] Lord Monck appointed Macdonald as the new nation's first prime minister. With the birth of the new nation, Canada East and Canada West became separate provinces, known as Quebec and Ontario, respectively.[83] Macdonald was appointed a Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath (KCB) on that first observance of what came to be known as Dominion Day, later called Canada Day, on 1 July 1867.[84]

Prime Minister of Canada

First majority, 1867–1871

Macdonald and his government faced immediate problems upon the formation of the new country. Much work remained to do in creating a federal government. Nova Scotia was already threatening to withdraw from the union; the Intercolonial Railway, which would both conciliate the Maritimes and bind them closer to the rest of Canada, was not yet built. Anglo-American relations were in a poor state, and Canadian foreign relations were matters handled from London. The withdrawal of the Americans in 1866 from the Reciprocity Treaty had increased tariffs on Canadian goods in US markets.[85] American and British opinion largely believed that the experiment of Confederation would quickly unravel, and the nascent nation absorbed by the United States.[86]

In August 1867, the new nation's first general election was held; Macdonald's party won easily, with strong support in both large provinces, and a majority from New Brunswick.[87] By 1869, Nova Scotia had agreed to remain part of Canada after a promise of better financial terms – the first of many provinces to negotiate concessions from Ottawa.[88] Pressure from London and Ottawa failed to gain the accession of Newfoundland, whose voters rejected a Confederation platform in a general election in October 1869.[89][90]

In 1869, John and Agnes Macdonald had a daughter, Mary. It soon became apparent that Mary had ongoing developmental issues; she was never able to walk, nor did she ever fully develop mentally.[91] Hewitt Bernard, Deputy Minister of Justice and Macdonald's former secretary, also lived in the Macdonald house in Ottawa, together with Bernard's widowed mother.[92] In May 1870, John Macdonald fell ill with gallstones; coupled with his frequent drinking, he may have developed a severe case of acute pancreatitis.[93] In July, he moved to Prince Edward Island to convalesce, most likely conducting discussions aimed at drawing the island into Confederation at a time when some there supported joining the United States.[94] The island joined Confederation in 1873.[95]

Macdonald had once been tepid on the question of westward expansion of the Canadian provinces; as prime minister, he became a strong supporter of a bicoastal Canada. Immediately upon Confederation, he sent commissioners to London who in due course successfully negotiated the transfer of Rupert's Land and the North-Western Territory to Canada.[96] The Hudson's Bay Company received £300,000 (CA$1,500,000) in compensation, and retained some trading posts as well as one-twentieth of the best farmland.[97] Prior to the date of acquisition, the Canadian government faced unrest in the Red River Colony (today southeastern Manitoba, centred on Winnipeg). The local people, including the Métis, were fearful that rule would be imposed on them which did not take into account their interests, and rose in the Red River Rebellion led by Louis Riel. Unwilling to pay for a territory in insurrection, Macdonald had troops put down the uprising before the formal transfer; as a result of the unrest, the Red River Colony joined Confederation as the province of Manitoba, while the rest of the purchased lands became the North-West Territories.[98]

Macdonald also wished to secure the colony of British Columbia. There was interest in the United States in bringing about the colony's annexation, and Macdonald wished to ensure his new nation had a Pacific outlet. The colony had an extremely large debt that would have to be assumed should it join Confederation. Negotiations were conducted in 1870, principally during Macdonald's illness and recuperation, with Cartier leading the Canadian delegation. Cartier offered British Columbia a railway linking it to the eastern provinces within ten years. The British Columbians, who privately had been prepared to accept far less generous terms, quickly agreed and joined Confederation in 1871.[99] The Canadian Parliament ratified the terms after a debate over the high cost that cabinet member Alexander Morris described as the worst fight the Conservatives had had since Confederation.[100]

There were continuing disputes with the Americans over deep-sea fishing rights, and in early 1871, an Anglo-American commission was appointed to settle outstanding matters between the British, the Canadians and the Americans. Canada was hoping to secure compensation for damage done by Fenians raiding Canada from bases in the United States. Macdonald was appointed a British commissioner, a post he was reluctant to accept as he realised Canadian interests might be sacrificed for the mother country. This proved to be the case; Canada received no compensation for the raids and no significant trade advantages in the settlement, which required Canada to open her waters to American fishermen. Macdonald returned home to defend the Treaty of Washington against a political firestorm.[101]

Second majority and Pacific Scandal, 1872–1873

In the run-up to the 1872 election, Macdonald had yet to formulate a railway policy, or to devise the loan guarantees that would be needed to secure the construction. During the previous year, Macdonald had met with potential railway financiers such as Hugh Allan and considerable financial discussion took place. The greatest political problem Macdonald faced was the Washington treaty, which had not yet been debated in Parliament.[102]

In early 1872, Macdonald submitted the treaty for ratification, and it passed the Commons with a majority of 66.[103] The general election was held through late August and early September. Redistribution had given Ontario increased representation in the House; Macdonald spent much time campaigning in the province, for the most part outside Kingston. Widespread bribery of voters took place throughout Canada, a practice especially effective in the era when votes were publicly declared. Macdonald and the Conservatives saw their majority reduced from 35 to 8.[104] The Liberals (as the Grits were coming to be known) did better than the Conservatives in Ontario, forcing the government to rely on the votes of Western and Maritime MPs who did not fully support the party.[105]

Macdonald had hoped to award the charter for the Canadian Pacific Railway in early 1872, but negotiations dragged on between the government and the financiers. Macdonald's government awarded the Allan group the charter in late 1872. In 1873, when Parliament opened, Liberal MP Lucius Seth Huntington charged that government ministers had been bribed with large, undisclosed political contributions to award the charter. Documents soon came to light which substantiated what came to be known as the Pacific Scandal. The Allan-led financiers, who were secretly backed by the United States's Northern Pacific Railway,[106] had donated $179,000 to the Tory election funds, they had received the charter, and Opposition newspapers began to publish telegrams signed by government ministers requesting large sums from the railway interest at the time the charter was under consideration. Macdonald had taken $45,000 in contributions from the railway interest himself. Substantial sums went to Cartier, who waged an expensive fight to try to retain his seat in Montreal East (he was defeated, but was subsequently returned for the Manitoba seat of Provencher). During the campaign Cartier had fallen ill with Bright's disease, which may have been causing his judgment to lapse;[107] he died in May 1873 while seeking treatment in London.[107]

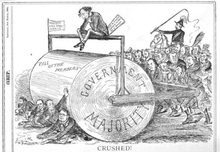

Before Cartier's death, Macdonald attempted to use delay to extricate the government.[108] The Opposition responded by leaking documents to friendly newspapers. On 18 July, three papers published a telegram dated August 1872 from Macdonald requesting another $10,000 and promising "it will be the last time of asking".[109] Macdonald was able to get a prorogation of Parliament in August by appointing a Royal Commission to look into the matter, but when Parliament reconvened in late October, the Liberals, feeling Macdonald could be defeated over the issue, applied immense pressure to wavering members.[110] On 3 November, Macdonald rose in the Commons to defend the government, and according to one of his biographer, P.B. Waite, he gave "the speech of his life, and, in a sense, for his life".[111] He began his speech at 9 p.m., looking frail and ill, an appearance which quickly improved. As he spoke, he consumed numerous glasses of gin and water. He denied that there had been a corrupt bargain, and stated that such contributions were common to both political parties. After five hours, Macdonald concluded,

I leave it with this House with every confidence. I am equal to either fortune. I can see past the decision of this House either for or against me, but whether it be against me or for me, I know, and it is no vain boast to say so, for even my enemies will admit that I am no boaster, that there does not exist in Canada a man who has given more of his time, more of his heart, more of his wealth, or more of his intellect and power, as it may be, for the good of this Dominion of Canada.[111]

Macdonald's speech was seen as a personal triumph, but it did little to salvage the fortunes of his government. With eroding support both in the Commons and among the public, Macdonald went to the Governor General, Lord Dufferin on 5 November, and resigned; Liberal leader Alexander Mackenzie became the second prime minister of Canada.[112] He is not known to have spoken of the events of the Pacific Scandal again.[113]

On 6 November 1873, Macdonald offered his resignation as party leader to his caucus; it was refused. Mackenzie called an election for January 1874; the Conservatives were reduced to 70 seats out of the 206 in the Commons, giving Mackenzie a massive majority.[114] The Conservatives bested the Liberals only in British Columbia; Mackenzie had called the terms by which the province had joined Confederation "impossible".[115] Macdonald was returned in Kingston but was unseated on an election contest when bribery was proven; he won the ensuing by-election by 17 votes. According to Swainson, most observers viewed Macdonald as finished in politics, "a used-up and dishonoured man".[116]

Opposition, 1873–1878

Macdonald was content to lead the Conservatives in a relaxed manner in opposition and await Liberal mistakes. He took long holidays and resumed his law practice, moving his family to Toronto and going into partnership with his son Hugh John.[117] One mistake that Macdonald believed the Liberals had made was a free-trade agreement with Washington, negotiated in 1874; Macdonald had come to believe that protection was necessary to build Canadian industry.[118] The Panic of 1873 had led to a worldwide depression; the Liberals found it difficult to finance the railway in such a climate, and were generally opposed to the line anyway – the slow pace of construction led to British Columbia claims that the agreement under which it had entered Confederation was in jeopardy of being broken.[119]

By 1876, Macdonald and the Conservatives had adopted protectionism as party policy. This view was widely promoted in speeches at a number of political picnics, held across Ontario during the summer of 1876. Macdonald's proposals were popular with the public, and the Conservatives began to win a string of by-elections. By the end of 1876, the Tories had picked up 14 seats as a result of by-elections, reducing Mackenzie's Liberal majority from 70 to 42.[120] Despite the success, Macdonald considered retirement, wishing only to reverse the voters' verdict of 1874 – he considered Charles Tupper his heir apparent.[121]

When Parliament convened in 1877, the Conservatives were confident and the Liberals defensive.[122] After the Tories had a successful session in the early part of the year, another series of picnics commenced in the areas around Toronto. Macdonald even campaigned in Quebec, which he had rarely done, leaving speechmaking there to Cartier.[123] More picnics followed in 1878, promoting proposals which would come to be collectively called the "National Policy": high tariffs, rapid construction of the transcontinental railway (the Canadian Pacific Railway or CPR), rapid agricultural development of the West using the railway, and policies which would attract immigrants to Canada.[124] These picnics allowed Macdonald venues to show off his talents at campaigning, and were often lighthearted – at one, the Tory leader blamed agricultural pests on the Grits, and promised the insects would go away if the Conservatives were elected.[125]

The final days of the 3rd Canadian Parliament were marked by explosive conflict, as Macdonald and Tupper alleged that MP and railway financier Donald Smith had been allowed to build the Pembina branch of the CPR (connecting to American lines) as a reward for betraying the Conservatives during the Pacific Scandal. The altercation continued even after the Commons had been summoned to the Senate to hear the dissolution read, as Macdonald spoke the final words recorded in the 3rd Parliament: "That fellow Smith is the biggest liar I ever saw!"[126]

The election was called for 17 September 1878. Fearful that Macdonald would be defeated in Kingston, his supporters tried to get him to run in the safe Conservative riding of Cardwell; having represented his hometown for 35 years, he stood there again. In the election, Macdonald was defeated in his riding by Alexander Gunn, but the Conservatives swept to victory.[127] Macdonald remained in the House of Commons, having quickly secured his election for Marquette, Manitoba; elections there were held later than in Ontario. His acceptance of office vacated his parliamentary seat, and Macdonald decided to stand for the British Columbia seat of Victoria, where the election was to be held on 21 October. Macdonald was duly returned for Victoria,[128] although he had never visited either Marquette or Victoria.[129]

Third and fourth majorities, 1878–1887

Part of the National Policy was implemented in the budget presented in February 1879. Under that budget, Canada became a high-tariff nation like the United States and Germany. The tariffs were designed to protect and build Canadian industry – finished textiles received a tariff of 34%, but the machinery to make them entered Canada free.[130] Macdonald continued to fight for higher tariffs for the remainder of his life.[131]

In January 1879, Macdonald commissioned politician Nicholas Flood Davin to write a report regarding the industrial boarding-school system in the United States.[132][133] Now known as the Davin Report, the Report on Industrial Schools for Indians and Half-Breeds was submitted to Ottawa on 14 March 1879, providing the basis for the Canadian Indian residential school system. It made the case for a cooperative approach between the Canadian government and the church to implement the "aggressive assimilation" pursued by President of the United States, Ulysses S. Grant.[134][133] In 1883, Parliament approved $43,000 for three industrial schools and the first, Battleford Industrial School, opened on 1 December of that year. By 1900, there were 61 schools in operation.[132] In 2015, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission concluded that the assimilation amounted to cultural genocide.[135]

By the 1880s, Macdonald was becoming frailer, but he maintained his political acuity. In 1883, he secured the "Intoxicating Liquors Bill" which took the regulation system away from the provinces, in part to stymie his foe Premier Mowat. In his own case, Macdonald took better control of his drinking and binges had ended. "The great drinking-bouts, the gargantuan in sobriety's of his middle years, were dwindling away now into memories."[136] As the budget moved forward, Macdonald found that the railway was progressing well: although little money had been spent on the project under Mackenzie, several hundred miles of track had been built and nearly the entire route surveyed. In 1880, Macdonald found a syndicate, led by George Stephen, willing to undertake the CPR project. Donald Smith (later Lord Strathcona) was a major partner in the syndicate, but because of the ill will between him and the Conservatives, Smith's participation was initially not made public, though it was well-known to Macdonald.[137] In 1880, the Dominion took over Britain's remaining Arctic territories, which extended Canada to its present-day boundaries, with the exception of Newfoundland, which did not enter Confederation until 1949. Also in 1880, Canada sent its first diplomatic representative abroad, Sir Alexander Galt as High Commissioner to Britain.[138] With good economic times, Macdonald and the Conservatives were returned with a slightly decreased majority in 1882. Macdonald was returned for the Ontario riding of Carleton.[139]

The transcontinental railroad project was heavily subsidised by the government. The CPR was granted 25,000,000 acres (100,000 km2; 39,000 sq mi) of land along the route of the railroad, and $25 million from the government. In addition, the government had to spend $32 million on the construction of other railways to support the CPR. The entire project was extremely costly, especially for a nation with only 4.1 million people in 1881.[140] Between 1880 and 1885, as the railway was slowly built, the CPR repeatedly came close to financial ruin. The terrain in the Rocky Mountains was difficult and the route north of Lake Superior proved treacherous, as tracks and engines sank into the muskeg.[141] When Canadian guarantees of the CPR's bonds failed to make them salable in a declining economy, Macdonald obtained a loan to the corporation from the Treasury – the bill authorizing it passed the Senate just before the firm would have become insolvent.[142]

The Northwest again saw unrest. Many of the Manitoban Métis had moved into the territories and negotiations between the Métis and the Government to settle grievances over land rights proved difficult. Riel, who had lived in exile in the United States since 1870, journeyed to Regina with the connivance of Macdonald's government, who believed he would prove a leader they could deal with.[143] Instead, the Métis rose the following year under Riel in the North-West Rebellion. Macdonald put down the rebellion with Canadian troops who were transported by rail, and Riel was captured, tried for treason, convicted, and hanged. Macdonald refused to consider reprieving Riel, who was of uncertain mental health. The hanging of Riel was controversial,[144] and alienated many Quebecers from the Conservatives and they were, like Riel, Catholic and culturally French Canadian; they soon realigned with the Liberals.[145] Following the North-West Rebellion of 1885, Macdonald's government implemented restrictions upon the movement of indigenous groups, requiring them to receive formal permission from an Indian Department Official in order to go off-reserve.[146]

The CPR was almost bankrupt, but Canada's decision to deploy troops in response to the crisis showed that the railway was helpful to maintain the territory's status as part of the British Empire, and the British Parliament provided money for its completion. On 7 November 1885, CPR manager William Van Horne wired Macdonald from Craigellachie, British Columbia, that the last spike had been driven, completing the railway.[147] That same year, the Macdonald government enacted the Chinese Immigration Act, 1885.[148] Macdonald told the House of Commons that, if the Chinese were not excluded from Canada, "the Aryan character of the future of British America should be destroyed".[149] In the summer of 1886, Macdonald travelled by rail to western Canada.[150] On 13 August 1886, Macdonald used a silver hammer and pounded a gold spike to complete the Esquimalt and Nanaimo Railway.[151]

In 1886, another dispute arose over fishing rights with the United States. Americans fishermen had been using treaty provisions allowing them to land in Canada to take on wood and water as a cover for clandestine inshore fishing. Several vessels were detained in Canadian ports, to the outrage of Americans, who demanded their release. Macdonald sought to pass a Fisheries Act which would override some of the treaty provisions, to the dismay of the British, who were still responsible for external relations. The British government instructed the Governor General, Lord Lansdowne, to reserve the bill for royal assent, effectively placing it on hold without vetoing it. After considerable discussion, the British government allowed royal assent at the end of 1886, and indicated it would send a warship to protect the fisheries if no agreement was reached with the Americans.[152]

Fifth and sixth majorities, 1887–1891

Fearing continued loss of political strength as poor economic times continued, Macdonald planned to hold an election by the end of 1886, but had not yet issued the writ when an Ontario provincial election was called by Liberal Ontario Premier Oliver Mowat. The provincial election was seen as a bellwether for the federal poll. Despite considerable campaigning by Macdonald, Mowat's Liberals were re-elected in Ontario and increased their majority.[152] Macdonald dissolved the federal Parliament on 15 January 1887, for an election on 22 February. During the campaign, the Quebec provincial Liberals formed a government (four months after the October 1886 Quebec election), forcing the Conservatives from power in Quebec City. Nevertheless, Macdonald and his cabinet campaigned hard in the winter election, with Tupper (the new High Commissioner to London) postponing his departure to try to bolster Conservative votes in Nova Scotia. The Liberal leader, Edward Blake, ran an uninspiring campaign, and the Conservatives were returned nationally with a majority of 35, winning easily in Ontario, Nova Scotia, and Manitoba. The Tories also took a narrow majority of Quebec's seats despite resentment over Riel's hanging. Macdonald became MP for Kingston once again.[153][154] Even the younger ministers, such as future Prime Minister John Thompson, who sometimes differed with Macdonald on policy, admitted Macdonald was an essential electoral asset for the Conservatives.[155]

Blake resigned after the defeat and was replaced by Wilfrid Laurier. Under Laurier's early leadership, the Liberals, who previously supported much of the National Policy, campaigned against it and called for "unrestricted reciprocity", or free trade, with the United States. Macdonald was willing to see some reciprocity with the United States, but was reluctant to lower many tariffs.[156] American advocates of what they dubbed "commercial union" saw it as a prelude to political union, and did not scruple to say so, causing additional controversy in Canada.[157]

Macdonald called an election for 5 March 1891. The Liberals were heavily financed by American interests; the Conservatives drew much financial support from the CPR. The 76-year-old prime minister collapsed during the campaign, and conducted political activities from his brother-in-law's house in Kingston. The Conservatives gained slightly in the popular vote, but their majority was reduced to 27.[158] The parties broke even in the central part of the country but the Conservatives dominated in the Maritimes and Western Canada, leading Liberal MP Richard John Cartwright to claim that Macdonald's majority was dependent on "the shreds and patches of Confederation". After the election, Laurier and his Liberals grudgingly accepted the National Policy; when Laurier later became prime minister, he adopted it with only minor changes.[159]

Death

In May 1891, Macdonald suffered a stroke which left him partially paralysed and unable to speak.[160] His health continued to deteriorate and he died in the late evening of 6 June 1891.[161] Thousands filed by his open casket in the Senate Chamber; his body was transported by funeral train to his hometown of Kingston, with crowds greeting the train at each stop. On arrival in Kingston, Macdonald lay in state in City Hall, wearing the uniform of an Imperial Privy Counsellor. He was buried in Cataraqui Cemetery in Kingston,[162] his grave near that of his first wife, Isabella.[163]

Legacy and memorials

Macdonald served just under 19 years as prime minister, a length of service only surpassed by William Lyon Mackenzie King.[164] In polls, Macdonald has consistently been ranked as one of the greatest prime ministers in Canadian history.[165] No cities or political subdivisions are named for Macdonald (with the exception of a small Manitoba village), nor are there any massive monuments.[166] A peak in the Rockies, Mount Macdonald (c. 1887) at Rogers Pass, is named for him.[167] In 2001, Parliament designated 11 January as Sir John A. Macdonald Day, but the day is not a federal holiday and generally passes unremarked.[166] He appears on Canadian ten-dollar notes printed between 1971 and 2018.[168][169] In 2015, the Royal Canadian Mint featured Macdonald's face on the Canadian two dollar coin, the Toonie, to celebrate his 200th birthday.[170] Macdonald's name is also used in Ottawa's Ottawa Macdonald–Cartier International Airport (renamed in 1993) and Ontario Highway 401 (the Macdonald–Cartier Freeway c. 1968).[166] His name is being phased out on Ottawa's Sir John A. Macdonald Parkway (River Parkway before 2012),[171] being renamed to an indigenous term, Kichi Zibi Mikan.[172][173] MacDonald also had a street named after him in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. This street, however, was changed to miyo-wâhkôhtowin, a Cree word meaning good relations, on 7 December 2023. This was done as a response to MacDonald playing a significant role in developing the Indian residential school system. [174][175][176][177]

A number of sites associated with Macdonald are preserved. His gravesite has been designated a National Historic Site of Canada.[178][179] Bellevue House in Kingston, where the Macdonald family lived in the 1840s, is also a National Historic Site administered by Parks Canada, and has been restored to that time period.[180] His Ottawa home, Earnscliffe, is the official residence of the British High Commissioner to Canada.[167] Statues have been erected to Macdonald across Canada;[181] one stands on Parliament Hill in Ottawa (by Louis-Philippe Hebert c. 1895).[182] A statue of Macdonald stands atop a granite plinth originally intended for a statue of Queen Victoria in Toronto's Queen's Park, looking south on University Avenue.[183] Macdonald's statue also stood in Kingston's City Park; the Kingston Historical Society annually holds a memorial service in his honour.[184] On 18 June 2021, following the discovery of 215 unmarked graves at the Kamloops Indian Residential School, the statue of Macdonald was removed from Kingston's City Park after city council voted 12–1 in favour of its removal, and is set to be installed at Cataraqui Cemetery where Macdonald is buried.[185] In 2018, a statue of Macdonald was removed from outside Victoria City Hall, as part of the city's program for reconciliation with local First Nations.[186] The Macdonald Monument in Montreal has been repeatedly vandalized, and on 29 August 2020, the statue in the monument was vandalized, toppled and decapitated.[187][188][189][190] Montreal Mayor Valérie Plante condemned the actions and said the city plans to restore the statue.[188]

Macdonald's biographers note his contribution to establishing Canada as a nation. Swainson suggests that Macdonald's desire for a free and tolerant Canada became part of its national outlook and contributed immeasurably to its character.[191] Gwyn said Macdonald's accomplishments of Confederation and building the Canadian railroad were great, but he was also responsible for scandals and bad government policy for the execution of Riel and the head tax on Chinese workers.[192] In 2017, the Canadian Historical Association had voted to remove Macdonald's name from their prize for best scholarly book about Canadian history. Historian James Daschuk acknowledges Macdonald's contributions as a founding figure of Canada, but states "He built the country. But he built the country on the backs of the Indigenous people."[193] A biographical online article about Macdonald was deleted from the Scottish government's website in August 2018. A spokesperson for the Scottish government stated: "We acknowledge controversy around Sir John A Macdonald's legacy and the legitimate concerns expressed by Indigenous communities".[194] On 5 July 2021, Canada's national library, Library and Archives Canada, deleted its web page on Canada's prime ministers, "First Among Equals", calling it "outdated and redundant".[195]

Honorary degrees

Macdonald was awarded the following honorary degrees:

| Location | Date | School | Degree |

|---|---|---|---|

| Canada West | 1863 | Queen's University at Kingston | Doctor of Laws (LL.D)[196] |

| 1865 | University of Oxford | Doctor of Civil Law (D.C.L.)[197][198] | |

| Ontario | 1889 | University of Toronto | Doctor of Laws (LL.D)[199] |

References

Notes

- ^ a b c The official birth record for John Alexander Mcdonald, proving the original spelling of the surname and official date of birth can be found in the National Records of Scotland or online at ScotlandsPeople using the following details:Parish: Glasgow, Parish Number: 644/1, Ref: 210 201, Parents/ Other Details: FR2265 (FR2265).

- ^ a b c Although 10 January is the official date recorded in the General Register Office in Edinburgh, 11 January is the day Macdonald and those who commemorate him have celebrated his birthday. See Gwyn 2007, p. 8.

Citations

- ^ "Ramshorn Cemetery Glasgow, Lanarkshire". Happy Haggis. Archived from the original on 2 August 2020. Retrieved 29 June 2017.

- ^ Phenix 2006, p. 6.

- ^ Gwyn 2007, p. 13.

- ^ Phenix 2006, p. 23.

- ^ a b Smith & McLeod 1989, p. 1.

- ^ Creighton 1952, p. 18.

- ^ Pope 1894, p. 4.

- ^ a b Swainson 1989, p. 19.

- ^ a b Creighton 1952, p. 19.

- ^ Pope 1894, p. 6.

- ^ Creighton 1952, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Gwyn 2007, pp. 46–47.

- ^ Creighton 1952, pp. 29–30.

- ^ Creighton 1952, pp. 32–34.

- ^ Phenix 2006, p. 38.

- ^ Phenix 2006, p. 41.

- ^ Phenix 2006, pp. 41–42.

- ^ Gwyn 2007, p. 49.

- ^ Library and Archives of Canada (1838). Canada, British Army and Canadian Militia Muster Rolls and Paylists, 1795–1850: Commcercial Bank Guard, 1837. Ottawa: Library and Archives of Canada.

- ^ Pope 1894, p. 9.

- ^ a b Blatherwick, John. "Prime Ministers of Canada Their Military Connections, Honours and Medals" (PDF). National Defence Historical Department. Retrieved 4 April 2023.

- ^ Johnson, J.K. (1968). The Papers of the Prime Ministers, Volume 1: The Letters of Sir John A. Macdonald, 1836–1857. Ottawa: Public Library of Canada.

- ^ Library and Archives of Canada (1838). Canada, British Army and Canadian Militia Muster Rolls and Paylists, 1795–1850: Commcercial Bank Guard, 1837. Ottawa: Library and Archives of Canada.

- ^ Library and Archives of Canada (1838). Canada, British Army and Canadian Militia Muster Rolls and Paylists, 1795–1850: Commcercial Bank Guard, 1837. Ottawa: Library and Archives of Canada.

- ^ Phenix 2006, p. 43.

- ^ Library and Archives of Canada (1838). Canada, British Army and Canadian Militia Muster Rolls and Paylists, 1795–1850: Frontenac Militia, 1838. Ottawa: Library and Archives of Canada.

- ^ Creighton 1952, pp. 53–54.

- ^ Creighton 1952, pp. 61–63.

- ^ Creighton 1952, p. 67.

- ^ Swainson 1989, p. 21.

- ^ Gwyn 2007, p. 58.

- ^ Swainson 1989, p. 23.

- ^ Phenix 2006, p. 56.

- ^ Phenix 2006, p. 57.

- ^ a b Phenix 2006, p. 59.

- ^ Gwyn 2007, p. 59.

- ^ Swainson 1989, p. 22.

- ^ Phenix 2006, pp. 63–64.

- ^ Swainson 1989, p. 25.

- ^ Gwyn 2007, p. 64.

- ^ Swainson 1989, p. 28.

- ^ Swainson 1989, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Phenix 2006, pp. 79–83.

- ^ Swainson 1989, pp. 30–31.

- ^ a b c Swainson 1989, p. 31.

- ^ Phenix 2006, p. 83.

- ^ Gwyn 2007, pp. 85–86.

- ^ Swainson 1989, p. 37.

- ^ Phenix 2006, p. 107.

- ^ Swainson 1989, pp. 40–42.

- ^ Gwyn 2007, p. 162.

- ^ Phenix 2006, pp. 124–125.

- ^ Swainson 1989, p. 42.

- ^ Phenix 2006, p. 129.

- ^ Phenix 2006, p. 130.

- ^ Creighton 1952, pp. 248–249.

- ^ Swainson 1989, pp. 46–47.

- ^ Gwyn 2007, pp. 175–177.

- ^ Swainson 1989, p. 48.

- ^ Gwyn 2007, pp. 194–195.

- ^ Gwyn 2007, p. 201.

- ^ Swainson 1989, p. 49.

- ^ a b Swainson 1989, pp. 52–53.

- ^ Christopher Klein (2020). When the Irish Invaded Canada: The Incredible True Story of the Civil War Veterans Who Fought for Ireland's Freedom. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. p. 42. ISBN 9-7805-2543-4016.

- ^ Bradley A. Rodgers (1996). Guardian of the Great Lakes: The U.S. Paddle Frigate Michigan. University of Michigan Press. p. 117. ISBN 9-7804-7206-6070.

- ^ Peter Kross (Fall 2015). "The Confederate Spy Ring: Spreading Terror to the Union". Warfare History network.

- ^ Laurence Armand French and Magdaleno Manzanarez (2017). North American Border Conflicts Race, Politics, and Ethics. Taylor & Francis. p. 190. ISBN 9-7813-5170-9873.

- ^ Swainson 1989, pp. 54–55.

- ^ Gwyn 2007, pp. 286–288.

- ^ Gwyn 2007, pp. 288–289.

- ^ Swainson 1989, pp. 63–65.

- ^ Swainson 1989, pp. 67–69.

- ^ Swainson 1989, p. 73.

- ^ Swainson 1989, p. 72.

- ^ Phenix 2006, p. 172.

- ^ Swainson 1989, p. 75.

- ^ Phenix 2006, p. 175.

- ^ Smith & McLeod 1989, p. 36.

- ^ Phenix 2006, pp. 176–177.

- ^ Swainson 1989, p. 76.

- ^ Gwyn 2007, p. 416.

- ^ Creighton 1952, p. 466.

- ^ Creighton 1952, pp. 470–471.

- ^ Swainson 1989, p. 79.

- ^ Swainson 1989, pp. 80–81.

- ^ Gwyn 2011, p. 3.

- ^ Creighton 1955, p. 2.

- ^ Swainson 1989, pp. 84–85.

- ^ Waite 1975, p. 76.

- ^ Gwyn 2011, p. 72.

- ^ Waite 1975, pp. 83–84.

- ^ Creighton 1955, p. 8.

- ^ Tristin Hopper (9 January 2015). "Everyone knows John A. Macdonald was a bit of a drunk, but it's largely forgotten how hard he hit the bottle". National Post.

- ^ Waite 1975, pp. 84–85.

- ^ Swainson 1989, p. 93.

- ^ Swainson 1989, pp. 85–86.

- ^ Mooney, Elizabeth. "Rupert's Land purchase". The Encyclopedia of Saskatchewan. University of Regina. Archived from the original on 13 October 2010. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- ^ Waite 1975, pp. 80–83.

- ^ Swainson 1989, pp. 91–92.

- ^ Creighton 1955, pp. 105–106.

- ^ Swainson 1989, pp. 93–94.

- ^ Creighton 1955, pp. 112–113.

- ^ Waite 1975, p. 97.

- ^ Waite 1975, pp. 97–100.

- ^ Swainson 1989, p. 96.

- ^ Gwyn 2011, p. 200.

- ^ a b Swainson 1989, pp. 97–100.

- ^ Creighton 1955, p. 156.

- ^ Waite 1975, p. 103.

- ^ Waite 1975, pp. 103–104.

- ^ a b Waite 1975, pp. 105–106.

- ^ Swainson 1989, pp. 102–103.

- ^ Gwyn 2011, p. 255.

- ^ Creighton 1955, pp. 180–183.

- ^ Gwyn 2011, p. 256.

- ^ Swainson 1989, p. 104.

- ^ Swainson 1989, pp. 105–107.

- ^ Creighton 1955, pp. 184–185.

- ^ Swainson 1989, p. 108.

- ^ Waite 1975, pp. 121–122.

- ^ Creighton 1955, p. 227.

- ^ Creighton 1955, pp. 228–230.

- ^ Creighton 1955, pp. 232–234.

- ^ Swainson 1989, p. 111.

- ^ Swainson 1989, pp. 111–112.

- ^ Creighton 1955, pp. 239–240.

- ^ Creighton 1955, pp. 241–242.

- ^ Bourinot 2008, p. 159.

- ^ Gwyn 2011, p. 299.

- ^ Gwyn 2011, p. 307.

- ^ Swainson 1989, pp. 115–16.

- ^ a b "Canada's Residential Schools: The History, Part 1 Origins to 1939: Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada Volume 1" (PDF). National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation. Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 March 2017. Retrieved 1 July 2016.

- ^ a b Davin, Nicholas Flood (1879). Report on industrial schools for Indians and half-breeds (microform) (Report). [Ottawa? : s.n., 1879?]. Archived from the original on 29 May 2016. Retrieved 11 July 2016.

- ^ Henderson & Wakeham 2013, p. 299.

- ^ "Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future: Summary of the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada" (PDF). National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation. Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. 31 May 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 July 2016. Retrieved 28 June 2016.

- ^ Creighton 1955, pp. 345, 347.

- ^ Swainson 1989, pp. 116–117.

- ^ Swainson 1989, p. 123.

- ^ Creighton 1955, p. 33.

- ^ Waite 1975, pp. 149–150.

- ^ Swainson 1989, pp. 118–119.

- ^ Creighton 1955, pp. 370–376.

- ^ Creighton 1955, pp. 385–388.

- ^ Waite 1975, pp. 159–162.

- ^ Swainson 1989, p. 138.

- ^ Stonechild 2006, p. 19.

- ^ Creighton 1955, p. 436.

- ^ Go, Avvy Yao-Yao; Lee, Brad (13 January 2014). "Should we really be celebrating Sir John A. Macdonald's birthday?". Toronto Star. Archived from the original on 30 December 2018. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- ^ Wherry, Aaron (21 August 2012). "Was John A. Macdonald a white supremacist?". Maclean's. Archived from the original on 21 October 2014.

- ^ Smith, Donald B.; Oosterom, Nelle (2017). "Worlds Apart". Canada's History. 97 (5): 30–37. ISSN 1920-9894.

- ^ "Last spike." Archived 8 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine Shawinigan Lake Museum. Retrieved on 21 July 2011.

- ^ a b Creighton 1955, pp. 454–456.

- ^ Creighton 1955, pp. 466–470.

- ^ Waite 1975, pp. 182–184.

- ^ Waite 1975, p. 185.

- ^ Swainson 1989, pp. 141–143.

- ^ Waite 1975, p. 203.

- ^ Waite 1975, pp. 208–209.

- ^ Swainson 1989, pp. 147–148.

- ^ Creighton 1955, p. 569.

- ^ Creighton 1955, p. 574–576.

- ^ "Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada – Former Prime Ministers and Their Grave Sites – The Right Honourable Sir John A. Macdonald". Parks Canada. Government of Canada. 20 December 2010. Archived from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- ^ Swainson 1989, pp. 149–152.

- ^ "Duration of Canadian Ministries." Archived 15 December 2015 at the Wayback Machine Parliament of Canada. Retrieved on 22 March 2011.

- ^ Azzi, S.; Hillmer, N. (7 October 2016). "Ranking Canada's best and worst prime ministers". Maclean's. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 7 September 2017.

- ^ a b c "The Legacy: Sir John A. Macdonald." Archived 23 February 2020 at the Wayback Machine Library and Archives Canada, 27 June 2008. Retrieved on 13 March 2011.

- ^ a b "Macdonald, The Right Hon. Sir John Alexander, P.C., G.C.B., Q.C., D.C.L., LL.D." ParlInfo. Parliament of Canada. Archived from the original on 22 August 2019. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- ^ "The Design of Canada's $10 Polymer Note" (PDF). Bank of Canada. May 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 August 2014. Retrieved 17 December 2014.

- ^ "New $10 bank note featuring Viola Desmond unveiled on International Women's Day" (Press release). Bank of Canada. 8 March 2018. Archived from the original on 8 March 2018. Retrieved 9 March 2018.

- ^ Payton, Laura (19 December 2014). "Sir John A. Macdonald toonie to celebrate 1st PM's 200th birthday". CBC. Archived from the original on 5 May 2016.

- ^ "Ottawa River Parkway renamed after Sir John A. Macdonald". CBC. 15 August 2012. Archived from the original on 28 January 2013. Retrieved 3 December 2012.

- ^ "New name for western Ottawa parkway". ottawa.ctvnews.ca. CTV News Ottawa. 22 June 2023. Retrieved 23 June 2023.

- ^ "Ottawa's Sir John A. Macdonald Parkway renamed Kichi Zībī Mīkan". cbc.ca. CBC News. 22 June 2023. Retrieved 23 June 2023.

- ^ "New name proposed for Saskatoon's John A. MacDonald Road". Saskatoon Star Phoenix. Retrieved 6 June 2024.

- ^ "Saskatoon's John A. Macdonald Road name change passed despite weeks of speed bumps". Global News. Retrieved 6 June 2024.

- ^ "miyo-wâhkôhtowin Road (formerly John A. Macdonald Road)". City of Saskatoon. Retrieved 6 June 2024.

- ^ "Former John A Macdonald Road officially renamed miyo wahkohtowin Road". CTV News. 7 December 2023. Retrieved 6 June 2024.

- ^ Sir John A. Macdonald Gravesite National Historic Site of Canada. Directory of Federal Heritage Designations. Parks Canada.

- ^ Sir John A. Macdonald Gravesite. Canadian Register of Historic Places. Retrieved 21 March 2011.

- ^ "Bellevue House National Historic Site of Canada: Discover". Parks Canada. 27 October 2017. Archived from the original on 11 December 2017.

- ^ "Sir John A. Macdonald by John Dann". Landmarks – Public Art in the Capital Region. LandmarksPublicArt.ca. Archived from the original on 10 July 2012. Retrieved 2 July 2013.

- ^ "Statues." Archived 1 March 2010 at the Wayback Machine Public Works and Government Services Canada. 4 August 2009. Retrieved on 20 March 2011.

- ^ Warkentin 2009, pp. 63–64.

- ^ "John A. Macdonald's Kingston". Kingston Historical Society. Archived from the original on 24 May 2012. Retrieved 20 February 2012.

- ^ "Sir John A. Macdonald statue removed from Kingston's City Park". globalnews.ca. 18 June 2021. Archived from the original on 28 June 2021. Retrieved 19 June 2021.

- ^ "John A. Macdonald statue removed from Victoria City Hall". CBC News. 11 August 2018. Archived from the original on 11 August 2018. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- ^ Rowe, Daniel J. (30 August 2020). "Statue of John A. Macdonald toppled during defund the police protest". CTV News. Archived from the original on 30 August 2020. Retrieved 30 August 2020.

- ^ a b "Activists topple statue of Sir John A. Macdonald in downtown Montreal". CBC.ca. 29 August 2020. Archived from the original on 30 August 2020. Retrieved 30 August 2020.

- ^ Fraser, Sara (19 June 2020). "Sir John A. Macdonald statue defaced overnight". CBC. Archived from the original on 11 March 2021. Retrieved 26 March 2021.

- ^ "Canada statue of John A Macdonald toppled by activists in Montreal". BBC. 30 August 2020. Archived from the original on 4 April 2021. Retrieved 26 March 2021.

- ^ Swainson 1989, p. 10.

- ^ Gwyn 2007, p. 3.

- ^ Hamilton, Graeme (18 May 2018). "'A key player in Indigenous cultural genocide:' Historians erase Sir John A. Macdonald's name from book prize". National Post. Archived from the original on 30 May 2018. Retrieved 25 August 2018.

- ^ Hopper, Tristin (20 August 2018). "Scottish government is actively distancing itself from John A. Macdonald: report". National Post.

- ^ Dawson, Tyler (6 July 2021). "Archives Canada removes 'outdated, redundant' web page about nation's prime ministers". National Post.

- ^ "Honorary Degrees" (PDF). Queen's University at Kingston. 14 September 2011. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 February 2020. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- ^ Foster, Joseph (1891). "Macdonald, (Sir) John Alexander". Alumni Oxonienses: the Members of the University of Oxford, 1715-1886. Vol. 3. Oxford: Parker and Co. p. 891. Archived from the original on 30 September 2021. Retrieved 29 September 2020.

- ^ Wallace, W. Stewart, ed. (1948). "SirJohn A. Macdonald". The Encyclopedia of Canada. Vol. IV. Toronto: University Associates of Canada. pp. 165–166. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 29 September 2020.

- ^ "Honorary Degree Recipients" (PDF). University of Toronto. 14 September 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 August 2019. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

Works cited

- Bourinot, John George (2008). Parliamentary Procedure and Practice in the Dominion of Canada. The Lawbook Exchange, Ltd. ISBN 978-1-58477-881-3.

- Creighton, Donald (1952). John A. Macdonald: The Young Politician, Vol 1: 1815–1867. Toronto: The Macmillan Company of Canada Limited. ISBN 978-0-307-37135-5. Archived from the original on 18 November 2015. Retrieved 18 November 2015.

- Creighton, Donald (1955). John A. Macdonald: The Old Chieftain, Vol 2: 1867–1891. Toronto: The Macmillan Company of Canada Limited. ISBN 978-0-8020-7164-4. Archived from the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- Gwyn, Richard (2007). John A., The Man Who Made Us: The Life and Times of Sir John A. Macdonald. Vol. 1: 1815–1867. Toronto: Random House Canada. ISBN 978-0-679-31475-2. Archived from the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- Gwyn, Richard (2011). Nation Builder: Sir John A. Macdonald: His Life, Our Times. Vol. 2: 1867–1891. Toronto: Random House Canada. ISBN 978-0-307-35644-4. Archived from the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- Henderson, Jennifer; Wakeham, Pauline, eds. (2013). "Appendix A: Aboriginal Peoples and Residential Schools". Reconciling Canada: Critical Perspectives on the Culture of Redress. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-1-4426-1168-9. Archived from the original on 13 June 2021. Retrieved 5 May 2017.

- McInnis, Edgar (1982). Canada: A political and social history. Holt. pp. 342–431. ISBN 978-0-0392-3177-4.

- Phenix, Patricia (2006). Private Demons: The Tragic Personal Life of John A. Macdonald (1st hardcover ed.). Toronto: McClelland & Stewart. ISBN 978-0-7710-7044-0.

- Pope, Joseph (1894). Memoirs of the Right Honourable Sir John Alexander Macdonald, G.C.B., First Prime Minister of The Dominion of Canada. Ottawa: J. Durie & Son.

- Smith, Cynthia; McLeod, Jack (1989). Sir John A.: An Anecdotal Life of John A. Macdonald. Don Mills, Ontario: Oxford University Press Canada. ISBN 978-0-19-540681-8.

- Stonechild, Blair (2006). The New Buffalo: The Struggle for Aboriginal Post-Secondary Education in Canada. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press. ISBN 9780887556937.

- Swainson, Donald (1989). Sir John A. Macdonald: The Man and the Politician. Kingston, ON: Quarry Press. ISBN 978-0-19-540181-3.

- Waite, P. B. (1975). Macdonald: His Life and World. Toronto: McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. ISBN 978-0-07-082301-3.

- Warkentin, Tim (2009). Creating Memory: A Guide to Toronto's Outdoor Sculpture. Toronto: Becker Associates. ISBN 978-0-919387-60-7. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 20 March 2011.

Further reading

- Bliss, Michael (2004). Right Honourable Men: The Descent of Canadian Politics from Macdonald to Mulroney (Updated ed.). Toronto: Harper Perennial Canada. ISBN 978-0-00-639484-6.

- Collins, Joseph Edmund (1883). Life and times of the Right Honourable Sir John A. Macdonald: Premier of the Dominion of Canada. Toronto: Rose Publishing Company. OCLC 562542085.

- Creighton, Donald (1964). The Road to Confederation: The Emergence of Canada: 1863–1867. Toronto: The Macmillan Company of Canada Ltd. ISBN 978-0-8371-8435-7.

- Creighton, Donald G. "John A. Macdonald, Confederation and the Canadian West". Transactions of the Manitoba Historical Society. Series 3 (23, 1966–67). Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 6 November 2015.

- Dutil, Patrice; Hall, Roger, eds. (2014). Macdonald at 200: New Reflections and Legacies. Toronto: Dundurn. ISBN 978-1-4597-2448-8. Archived from the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 8 September 2019.; essays by scholars

- Gwyn, Richard J. (2012). "Canada's Father Figure". Canada's History. Vol. 92, no. 5. pp. 30–37. Archived from the original on 6 September 2019. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

- Johnson, J.K.; Waite, P.B. (1990). "Macdonald, Sir John Alexander". In Halpenny, Francess G (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. XII (1891–1900) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- Macdonald, John A. (1910). . W. S. Johnston – via Wikisource. This author is different from the subject of this page, and lived 1846–1922. Since the copyright has run out, there exist today many reprints.

- Martin, Ged (2007). "John A. Macdonald: Provincial Premier". British Journal of Canadian Studies. 20 (1): 99–122. doi:10.3828/bjcs.20.1.5. Archived from the original on 6 September 2019. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

Historiography

- Dutil, Patrice; Hall, Roger, eds. (2014). Macdonald at 200: New Reflections and Legacies. Toronto: Dundurn. ISBN 978-1-4597-2448-8., essays by scholars

- Symons, Thomas H.B. (Summer 2015). "John A. Macdonald: A founder and builder" (PDF). Canadian Issues. pp. 6–10.

Primary sources

- Gibson, Sarah Katherine; Milnes, Arthur, eds. (2014). Canada Transformed: The Speeches of Sir John A. Macdonald: A Bicentennial Celebration. McClelland and Stewart. ISBN 9780771057199.; mostly drawn from debates in Parliament

- Johnson, J.K. (1969). Affectionately Yours: The Letters of Sir John A. Macdonald and His Family. Toronto: The Macmillan Company of Canada, Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7705-1017-6.

External links

- "Topic – Sir John A. Macdonald: Architect of Modern Canada". CBC. Retrieved 30 August 2012.

- Library and Archives Canada: gallery of papers

- Bruce, Henry (1893). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 35. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 43–46.

- Parkin, George Robert (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 17 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 211–212.

- Johnson, J.K. (12 December 2018). "Sir John A. Macdonald". The Canadian Encyclopedia (online ed.). Historica Canada.

- Sir John A. Macdonald fonds at Library and Archives Canada

- John A. Macdonald collection, Archives of Ontario

- John A. Macdonald

- 1815 births

- 1891 deaths

- 19th-century Scottish people

- Canadian Anglicans

- Canadian King's Counsel

- Ministers of railways and canals of Canada

- Canadian monarchists

- Canadian people of Scottish descent

- Converts to Anglicanism from Presbyterianism

- Fathers of Confederation

- Canadian Knights Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George

- Canadian Knights Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath

- Lawyers in Ontario

- Leaders of the Conservative Party of Canada (1867–1942)

- Leaders of the Opposition (Canada)

- Macdonald family

- Members of the House of Commons of Canada from Ontario

- Members of the Legislative Assembly of the Province of Canada from Canada West

- Canadian members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom

- Members of the King's Privy Council for Canada

- Persons of National Historic Significance (Canada)

- Politicians from Glasgow

- People from Kingston, Ontario

- Premiers of the Province of Canada