P. D. James

The Baroness James of Holland Park | |

|---|---|

James in 2013 | |

| Born | Phyllis Dorothy James 3 August 1920 Oxford, England |

| Died | 27 November 2014 (aged 94) Oxford, England |

| Pen name | P. D. James |

| Occupation | Novelist |

| Genre | |

| Spouse |

Ernest Connor Bantry White

(m. 1941; died 1964) |

| Children | 2 |

Phyllis Dorothy James White, Baroness James of Holland Park, OBE, FRSA, FRSL (3 August 1920 – 27 November 2014), known professionally as P. D. James, was an English novelist and life peer. Her rise to fame came with her series of detective novels featuring the police commander and poet, Adam Dalgliesh.[2]

Life and career

[edit]James was born in Oxford, the daughter of Sidney Victor James, a tax inspector, and his wife, Dorothy Mary James.[3] She was educated at the British School[4] in Ludlow and Cambridge High School for Girls.[5] Her mother was committed to a mental hospital when James was in her mid-teens.[6]

She had to leave school at the age of sixteen to work to take care of her younger siblings, sister Monica, and brother Edward, because her family did not have much money and her father did not believe in higher education for girls.[citation needed] She worked in a tax office in Ely for three years and later found a job as an assistant stage manager for the Festival Theatre in Cambridge.[7] She married Ernest Connor Bantry White (called "Connor"), an army doctor, on 8 August 1941.[7] They had two daughters, Clare and Jane.

White returned from the Second World War mentally ill and was institutionalised. With her daughters being mostly cared for by Connor's parents,[8] James studied hospital administration, and from 1949 to 1968 worked for a hospital board in London.[9] She began writing in the mid-1950s, using her maiden name ("My genes are James genes").[10][11]

Her first novel, Cover Her Face, featuring the investigator and poet Adam Dalgliesh of New Scotland Yard, was published in 1962.[12] Dalgliesh's last name comes from a teacher of English at Cambridge High School and his first name is that of Miss Dalgliesh's father.[13] Many of James's mystery novels take place against the backdrop of UK bureaucracies, such as the criminal justice system and the National Health Service, in which she worked for decades starting in the 1940s. Two years after the publication of Cover Her Face, James's husband died on 5 August 1964.[14] Prior to his death, James had not felt able to change her job: "He [Connor] would periodically discharge himself from hospital, sometimes at very short notice, and I never knew quite what I would have to face when I returned home from the office. It was not a propitious time to look for promotion or for a new job, which would only impose additional strain. But now [after Connor's death] I felt the strong need to look for a change of direction."[15] She applied for the grade of Principal in the Home Civil Service[14] and held positions as a civil servant within several sections of the Home Office, including the criminal section. She worked in government service until her retirement in 1979.

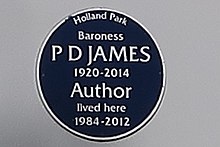

On 7 February 1991, James was created a life peer as Baroness James of Holland Park, of Southwold in the County of Suffolk.[16] She sat in the House of Lords as a Conservative. She was an Anglican and a lay patron of the Prayer Book Society. Her 2001 work, Death in Holy Orders, displays her familiarity with the inner workings of church hierarchy.[17] Her later novels were often set in a community closed in some way, such as a publishing house, barristers' chambers, a theological college, an island or a private clinic. Talking About Detective Fiction was published in 2009. Over her writing career, James also wrote many essays and short stories for periodicals and anthologies, which have yet to be collected. She revealed in 2011 that The Private Patient was the final Dalgliesh novel.[18]

As guest editor of BBC Radio 4's Today programme in December 2009, James conducted an interview with the Director General of the BBC, Mark Thompson, in which she seemed critical of some of his decisions. Regular Today presenter Evan Davis commented that "She shouldn't be guest editing; she should be permanently presenting the programme."[19] In 2008, she was inducted into the International Crime Writing Hall of Fame at the inaugural ITV3 Crime Thriller Awards.[20]

In August 2014, James was one of 200 public figures who were signatories to a letter to The Guardian opposing Scottish independence in the run-up to September's referendum on that issue.[21]

James' main home was her house at 58 Holland Park Avenue, in the area from which she took her title; she also owned homes in Oxford and Southwold.

James died at her home in Oxford on 27 November 2014, aged 94.[22] She is survived by her two daughters, Clare and Jane, five grandchildren and eight great-grandchildren.[23]

Film and television

[edit]During the 1980s, many of James's mystery novels were adapted for television by Anglia Television for the ITV network in the UK. These productions have been broadcast in other countries, including the US on the PBS network. Roy Marsden played Adam Dalgliesh. According to James in conversation with Bill Link on 3 May 2001 at the Writer's Guild Theatre, Los Angeles, Marsden "is not my idea of Dalgliesh, but I would be very surprised if he were."[24] The BBC adapted Death in Holy Orders in 2003, and The Murder Room in 2004, both as one-off dramas starring Martin Shaw as Dalgliesh. In Dalgliesh (2021), Bertie Carvel starred as the titular, enigmatic detective–poet. Six episodes, shown as three two-parters, premiered on Acorn TV on 1 November 2021 in the United States followed by a Channel 5 premiere on 4 November in the United Kingdom. A further six episodes started to air on Channel 5 in April 2023.

Her novel The Children of Men (1992) was the basis for the feature film Children of Men (2006), directed by Alfonso Cuarón and starring Clive Owen, Julianne Moore and Michael Caine.[25] Despite substantial changes from the book, James was reportedly pleased with the adaptation and proud to be associated with the film.[26]

A three-episode adaptation of her novel Death Comes to Pemberley, written by Juliette Towhidi, was made into the TV series Death Comes to Pemberley by Origin Pictures for BBC One. It was first shown in the UK over three nights from 26 December 2013 as part of the BBC's Christmas schedule and stars Anna Maxwell Martin as Elizabeth, Matthew Rhys as Mr Darcy, Jenna Coleman as Lydia and Matthew Goode as Wickham.

Books

[edit]

Novels[edit]Adam Dalgliesh mysteries

Cordelia Gray mysteries

Miscellaneous novels

|

Omnibus editions[edit]

Nonfiction[edit]

|

Short stories

[edit]- "Moment of Power" (1968), first published in Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, July 1968 (collected as "A Very Commonplace Murder" in The Mistletoe Murder and Other Stories, 2016)

- "The Victim" (1973), first published in Winter's Crimes 5, ed. Virginia Whitaker (collected in Sleep No More: Six Murderous Tales, 2017)

- "Murder, 1986" (1975), first published in Ellery Queen's Masters of Mystery

- "A Very Desirable Residence" (1976), first published in Winter's Crimes 8, ed. Hilary Watson (collected in Sleep No More: Six Murderous Tales, 2017)

- "Great-Aunt Ellie's Flypapers" (1979), first published in Verdict of Thirteen, ed. Julian Symons (collected as "The Boxdale Inheritance" in The Mistletoe Murder and Other Stories, 2016)

- "The Girl Who Loved Graveyards" (1983), first published in Winter's Crimes 15, ed. George Hardinge (collected in Sleep No More: Six Murderous Tales, 2017)

- "Memories Don't Die" (1984), first published in Redbook, July 1984

- "The Murder of Santa Claus" (1984), first published in Great Detectives, ed. D. W. McCullough (collected in Sleep No More: Six Murderous Tales, 2017)

- "The Mistletoe Murder" (1991), first published in The Spectator (collected in The Mistletoe Murder and Other Stories, 2016)

- "The Man Who Was 80" (1992), first published in The Illustrated London News, 1 November 1992, and The Man Who, later revised as "Mr. Maybrick's Birthday" c. 2005 (collected as "Mr. Millcroft's Birthday" in Sleep No More: Six Murderous Tales, 2017)

- "The Part-time Job" (2005), first published in The Detection Collection, ed. Simon Brett

- "Hearing Ghote" (2006), first published in The Verdict of Us All, ed. Peter Lovesey. An earlier version of the story ("The Yo-Yo") written in 1996 was later published in Sleep No More: Six Murderous Tales in 2017.

- "The Twelve Clues of Christmas" (collected in The Mistletoe Murder and Other Stories, 2016)

TV and film adaptations

[edit]Adam Dalgliesh series

[edit]- Death of an Expert Witness (1983)

- Shroud for a Nightingale (1984)

- Cover Her Face (1985)

- The Black Tower (1985)

- A Taste For Death (1988)

- Devices and Desires (1991)

- Unnatural Causes (1993)

- A Mind to Murder (1995)

- Original Sin (1997)

- A Certain Justice (1998)

- Death in Holy Orders (2003)

- The Murder Room (2003)

- Dalgliesh (2021)

Other adaptations

[edit]- An Unsuitable Job for a Woman (1982, 1997–1998, 1999–2001)

- Children of Men (feature film)[25] (2006)

- Death Comes to Pemberley (2011)

Selected awards and honours

[edit]Honours

[edit]- Officer of the Order of the British Empire, 1983[27]

- Associate Fellow of Downing College, Cambridge, 1986[28]

- Life peerage, Baroness James of Holland Park, of Southwold in the County of Suffolk, 7 February 1991[16]

- Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature[29]

- Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts[29]

- President of the Society of Authors 1997–2013[30]

Honorary doctorates

- University of Buckingham, 1992[31]

- University of Hertfordshire, 1994[31]

- University of Glasgow, 1995[31]

- University of Essex, 1996[31]

- University of Durham, 1998[31]

- University of Portsmouth, 1999[31]

- University of London, 1993[31]

Honorary fellowships

- St Hilda's College, Oxford, 1996[31]

- Girton College, Cambridge, 2000[31]

- Downing College, Cambridge, 2000[32]

- Kellogg College, Oxford[33]

- Lucy Cavendish College, Cambridge, 2012

Awards

[edit]- 1971 Best Novel Award, Mystery Writers of America (runner-up): Shroud for a Nightingale

- 1972 Crime Writers' Association (CWA) Macallan Silver Dagger for Fiction: Shroud for a Nightingale[34]

- 1973 Best Novel Award, Mystery Writers of America (runner-up): An Unsuitable Job for a Woman[31]

- 1976 CWA Macallan Silver Dagger for Fiction: The Black Tower[35]

- 1986 Mystery Writers of America Best Novel Award (runner-up): A Taste for Death[31]

- 1987 CWA Macallan Silver Dagger for Fiction: A Taste for Death[36]

- 1987 CWA Cartier Diamond Dagger (lifetime achievement award)[37]

- 1992 Deo Gloria Award: The Children of Men[38]

- 1992 The Best Translated Crime Fiction of the Year in Japan, Kono Mystery ga Sugoi! 1992: Devices and Desires

- 1999 Grandmaster Award, Mystery Writers of America[31]

- 2002 WH Smith Literary Award (shortlist): Death in Holy Orders[31]

- 2005 British Book Awards Crime Thriller of the Year (shortlist): The Murder Room[31]

- 2010 Best Critical Nonfiction Anthony Award for Talking About Detective Fiction[31]

- 2010 Nick Clarke Award for interview with Director-General of the BBC Mark Thompson whilst guest editor of Today radio programme.[39]

|

|

Interviews

[edit]- Shusha Guppy (Summer 1995). "P. D. James, The Art of Fiction No. 141". The Paris Review. Summer 1995 (135).

- The Guardian, 4-3-01. Accessed 2010-09-15

- The Sunday Herald newspaper (U.K.), 13-9-08[permanent dead link]. Accessed 2010-09-15

- CBC Radio hour-long interview by Eleanor Wachtel, 2000. Accessed 2 Aug. 2020

- The Globe and Mail (Canada), 30-1-09. Accessed 2010-09-15

- The Daily Telegraph newspaper (U.K.), 21-7-10. Accessed 2010-09-15

- The Independent newspaper (U.K.), 29-9-08. Accessed 2010-09-15

- The American Spectator magazine (U.S.), 4-1-10. Accessed 2010-09-15

- Extended audio discussion on Death Comes to Pemberley for the Faber website. Recorded October 2011.

- Video interview discussing Death Comes to Pemberley. Filmed October 2011.

References

[edit]- ^ "PD James". Front Row. 3 June 2013. BBC Radio 4. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- ^ "Alphabetical List of Members", House of Lords, UK: Parliament.

- ^

- dedication page of Time To Be in Earnest, 1999

- "P D James". UK Civil Service. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

P D James was born in 1920 in Walton Street, Oxford

- ^

- "'Century of Change 1900-2000: Memories of Ludlow Grammar School, Ludlow Girls' High School, Ludlow College', 2000 - 2002". Personal Papers of P D James, 1877 - 2017. Girton College Archive. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- Webb, Richard. "St Laurence's C of E Primary School". Geograph. geograph.org.uk. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

In 1972 St Laurence's C of E Primary School closed. It merged with the former British School on Old Street and Ludlow had just one primary school. This is the site of the shared sports field of the two schools.

- James, P. D. (1 August 2020). "I'll never forget my first love". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- Symons, Julian. "THE QUEEN OF CRIME: P.D. JAMES: Book Review". The New York Times. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

When I was a child, at Ludlow in Shropshire, I saw children going to school without coats or shoes. There was real poverty in a lot of homes.

- Wallace, David (2 December 2014). "Letter: PD James, a Shropshire lass". the Guardian. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

We used to explore all the paths around the castle, all around the hill. Down below there was the river Teme and the water meadows. I can remember very, very clearly the school I went to, and the names of some of the children come right back to me. The British school, it was called, and the earliest poem I learned there was called Mamble.

- "Remembering P.D. James". The Prayer Book Society of Canada. 6 February 2015. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

Later, at a church school in Ludlow, Shropshire, she was required to learn the Collect each week.

- "Desert Island Discs: P D James". BBC Radio 4. BBC. 2002. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

Sue Lawley's castaway is crime writer and conservative life peer P D James.

- "Desert Island Discs: P D James". BBC Radio 4. BBC. 1982. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

Roy Plomley's castaway is writer P D James.

- "P D James". Desert Island Discs: Archive 2000-2005. Apple Podcasts. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

Phyllis attended an old-fashioned grammar school where she enjoyed English lessons

- https://4degreesbrewing.com/hill-70-info/corporal-acton/

- https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/a/A13533016

- https://www.ludlowsoldiersww1.co.uk/page.php?n=Rogers,%20William%20Ernest

- ^

- "Faber & Faber: P. D. James". Faber.co.uk. 22 September 2008. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- "About". P. D. James. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- ^ Slade, Douglas (28 November 2014). "PD James dead: Remembering the first lady of crime". Express.co.uk. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

The family moved to Ludlow, Shropshire, for her primary school years and then to Cambridge, where she went to the County High School for Girls. When she was in her mid-teens her mother was committed to a mental hospital.

- ^ a b Time To Be in Earnest, p. 20

- ^ Time To Be in Earnest, p. 113, p.115, p. 179, and p. 226

- ^ Emma Brockes, The Guardian profile: P D James – "Murder She Wrote", 3 March 2001. Accessed 20 January 2013

- ^ "P.D. James: About the Author P.D. James". randomhouse.com.

- ^ Enright, Michael (30 December 2018) [2014]. The Sunday Edition - December 30, 2018 (Radio interview). CBC. Event occurs at 26:30.

- ^ Reese, Jennifer (26 February 1998). "The Salon Interview – P.D. James – The Art of Murder". Salon. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011.

- ^ Time To Be in Earnest, p. 48

- ^ a b Time To Be in Earnest, p. 115

- ^ A Time To Be in Earnest, p. 115

- ^ a b "No. 52448". The London Gazette. 13 February 1991. p. 2255.

- ^ "Why I am still an Anglican", Continuum, 2006, p. 16.

- ^ Sarah Crown (4 November 2011). "A life in writing: PD James". The Guardian.

- ^ John Plunkett (31 December 2009). "BBC director general Mark Thompson thrown by PD James's detective work". The Guardian.

- ^ Allen, Katie (6 October 2008). "Rankin and P D James pick up ITV3 awards". theBookseller.com. Archived from the original on 9 April 2009. Retrieved 6 October 2008.

- ^ "Celebrities' open letter to Scotland – full text and list of signatories | Politics". theguardian.com. 7 August 2014. Retrieved 26 August 2014.

- ^ "PD James, crime novelist, dies aged 94". BBC News. 27 November 2014. Retrieved 27 November 2014.

- ^ Reynolds, Stanley (27 November 2014). "PD James obituary". The Guardian. Retrieved 27 November 2014.

- ^ "P.D. James with Bill Link". Writers Bloc. 3 May 2001. Retrieved 27 November 2014.

- ^ a b Children of Men at IMDB

- ^ "P. D. James Pleased With Film Version of Children of Men". internetwritingjournal.com. 8 January 2007. Retrieved 20 May 2008.

- ^ "No. 49375". The London Gazette (Supplement). 11 June 1983. p. 10.

- ^ "P D James on Desert Island Discs". BBC. 27 October 2002.

- ^ a b Reynolds, Stanley (27 November 2014). "PD James obituary". The Guardian. London.

- ^ Flood, Alison (25 March 2013). "Philip Pullman to be Society of Authors' new president". The Guardian. London.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "Baroness James of Holland Park P. D. James". British Council. Retrieved 27 November 2014.

- ^ Stafford, Sandra (2008), "The puzzle beneath the prize", The Downing College Magazine, 19: 4–6

- ^ British Council. "Baroness James of Holland Park P. D. James - British Council Literature". contemporarywriters.com.

- ^ "The Dagger Awards Winners Archive – 1972". Crime Writers' Association. Retrieved 27 November 2014.

- ^ "The Dagger Awards Winners Archive – 1976". Crime Writers' Association. Retrieved 27 November 2014.

- ^ "The Dagger Awards Winners Archive – 1987". Crime Writers' Association. Retrieved 27 November 2014.

- ^ "The Cartier Diamond Dagger". Crime Writers' Association. Archived from the original on 4 December 2014. Retrieved 27 November 2014.

- ^ "Deo Gloria Book Awards". Deo Gloria Trust. Retrieved 27 November 2014.

- ^ "PD James wins BBC's Nick Clarke Award for journalism". New Statesman. UK. 12 October 2010.

- ^ Debrett's Peerage. 2003. p. 861.

Further reading

[edit]- Gidez, Richard B. P. D. James. Twayne's English Authors Series. New York: Twayne, 1986.

- Hubly, Erlene. "Adam Dalgliesh: Byronic Hero." Clues: A Journal of Detection 3: 40–46.

- Joshi, S. T. "P. D. James: The Empress's New Clothes." In Varieties of Crime Fiction (Wildside Press, 2019) ISBN 978-1-4794-4546-2.

- Knight, Stephen. "The Golden Age". In The Cambridge Companion to Crime Fiction ed. by Martin Priestman, pp 77–94. (Cambridge University Press, 2003).

- Kotker, Joan G. "PD James's Adam Dalgliesh Series." in In the Beginning: First Novels in Mystery Series (1995): 139+

- Sharkey, Jo Ann. Theology in suspense: how the detective fiction of PD James provokes theological thought. (PhD Dissertation, University of St Andrews, 2011). online; with long bibliography

- Siebenheller, Norma. P. D. James. (New York: Ungar, 1981).

- Smyer, Richard L. "P.D. James: Crime and the Human Condition". Clues 3 (Spring/Summer 1982): 49–61.

- Wood, Ralph C. "A Case for P.D. James as a Christian Novelist". Theology Today 59.4 (January 2003): 583–595.

- Young, Laurel A. P. D. James: A Companion to the Mystery Fiction. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2017. ISBN 978-0-7864-9791-1

External links

[edit]- The British Council's Contemporary Writers. Accessed 2016-08-03

- Faber and Faber (U.K.), publisher. Accessed 2010-09-15

- Random House (U.S.), publisher. Accessed 2010-09-15

- Penguin Books (U.K.), publisher. Accessed 2010-09-15

- P. D. James at IMDb

- Portraits of P. D. James at the National Portrait Gallery, London

- "P.D. James (Baroness James of Holland Park OBE JP)", Fellows Remembered, The Royal Society of Literature.

- 1920 births

- 2014 deaths

- Anglo-Catholic writers

- Anthony Award winners

- BBC Governors

- British mystery writers

- Cartier Diamond Dagger winners

- Conservative Party (UK) life peers

- Edgar Award winners

- English Anglo-Catholics

- English crime fiction writers

- English women novelists

- Fellows of Girton College, Cambridge

- Fellows of the Royal Society of Literature

- Life peeresses created by Elizabeth II

- Literary peers

- Macavity Award winners

- Members of the Detection Club

- Officers of the Order of the British Empire

- People from Southwold

- Pseudonymous women writers

- British women mystery writers

- Women science fiction and fantasy writers

- Writers from Oxford

- 20th-century English novelists

- 20th-century English women writers

- 20th-century pseudonymous writers

- Presidents of the Society of Authors

- Fellows of the Royal Society of Arts