SARS-CoV-2 Epsilon variant

Legend:

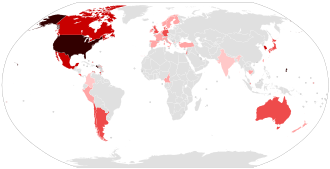

Epsilon variant, also known as CAL.20C and referring to two PANGO lineages B.1.427 and B.1.429, is one of the variants of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. It was first detected in California, USA in July 2020.[1]

As of March 2022, Epsilon is considered as a previously circulating variant of interest by the WHO. It is considered a variant being monitored by the CDC.

Mutations[edit]

The variant has five defining mutations (I4205V and D1183Y in the ORF1ab gene, and S13I, W152C, L452R in the spike protein's S-gene),[2] of which the L452R (previously also detected in other unrelated lineages) was of particular concern.[3] B.1.429 is possibly more transmissible than previous variants circulating locally, but further study is necessary to confirm this.[3] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has listed B.1.429 and the related B.1.427 as "variants of concern", and cites a preprint for saying that they exhibit a ~20% increase in viral transmissibility, that they have a "Significant impact on neutralization by some, but not all" therapeutics that have been given Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treatment or prevention of COVID-19, and that they moderately reduce neutralization by plasma collected by people who have previously been infected by the virus or who have received a vaccine against the virus.[4][5] In May 2021, the World Health Organization (WHO) gave the variant the name 'Epsilon variant'.[6]

-

Amino acid mutations of SARS-CoV-2 Epsilon variant plotted on a genome map of SARS-CoV-2 with a focus on the spike.[7]

| Part of a series on the |

| COVID-19 pandemic |

|---|

|

|

|

|

History[edit]

Epsilon (CAL.20C) was first observed in July 2020 by researchers at the Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, California, in one of 1,230 virus samples collected in Los Angeles County from the start of the COVID-19 epidemic.[1] It was not detected again until September when it reappeared among samples in California, but numbers remained very low until November.[8][9] In November 2020, the Epsilon variant accounted for 36 percent of samples collected at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, and by January 2021, the Epsilon variant accounted for 50 percent of samples.[3] In a joint press release by University of California, San Francisco, California Department of Public Health, and Santa Clara County Public Health Department,[10] it was announced that the variant was also detected in multiple counties in Northern California. From November to December 2020, the frequency of the variant in sequenced cases from Northern California rose from 3% to 25%.[11] A preprint describes CAL.20C as belonging to Nextstrain clade 20C and contributing approximately 36% of samples, while an emerging variant from the 20G clade accounts for some 24% of the samples in a study focused on Southern California. However, in the US as a whole, the 20G clade predominated as of January 2021. Following the increasing numbers of Epsilon in California, the variant has been detected at varying frequencies in most US states. Small numbers have been detected in other countries in North America, and in Europe, Asia and Australia.[8][9] As of July 2021, the Epsilon variant had been detected in 45 countries, according to GISAID.[12] After an initial increase, its frequency rapidly decreased from February 2021 as it was being outcompeted by the more transmissible Alpha variant. In April, Epsilon remained relatively frequent in parts of northern California, but it had virtually disappeared from the south of the state and had never been able to establish itself elsewhere; only 3.2% of all cases in the United States were Epsilon, whereas by then more than two-thirds were Alpha.[13]

Statistics[edit]

See also[edit]

- Variants of SARS-CoV-2: Alpha, Beta, Gamma, Delta, Zeta, Eta, Theta, Iota, Kappa, Lambda, Mu, Omicron

References[edit]

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Local COVID-19 Strain Found in Over One-Third of Los Angeles Patients". news wise (Press release). California: Cedars Sinai Medical Center. January 19, 2021. Retrieved March 3, 2021.

- ^ Spike Variants: Epsilon, aka B.1.427/B.1.429, and CAL.20C/S:452R covdb.stanford.edu, accessed 3 July 2021

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "New California Variant May Be Driving Virus Surge There, Study Suggests". The New York Times. January 19, 2021.

- ^ "SARS-CoV-2 Variant Classifications and Definitions". CDC.gov. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. March 24, 2021. Retrieved April 4, 2021.

- ^ Shen X, Tang H, Pajon R, Smith G, Glenn GM, Shi W, et al. (April 2021). "Neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 Variants B.1.429 and B.1.351". The New England Journal of Medicine. 384 (24): 2352–2354. doi:10.1056/NEJMc2103740. PMC 8063884. PMID 33826819.

- ^ Helen Branswell The name game for coronavirus variants just got a little easier 31 May 2021 www.statnews.com, accessed 28 June 2021

- ^ "Spike Variants: Epsilon variant, aka B.1.427/B.1.429". covdb.stanford.edu. Stanford University Coronavirus Antiviral & Resistance Database. July 1, 2021. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "B.1.429". Rambaut Group, University of Edinburgh. PANGO Lineages. February 15, 2021. Archived from the original on April 28, 2021. Retrieved February 16, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "B.1.429 Lineage Report". Scripps Research. outbreak.info. February 15, 2021. Retrieved February 16, 2021.

- ^ "COVID-19 Variant First Found in Other Countries and States Now Seen More Frequently in California". California Department of Public Health. Retrieved January 30, 2021.

- ^ Weise E, Weintraub K. "New strains of COVID swiftly moving through the US need careful watch, scientists say". USA Today. Retrieved January 30, 2021.

- ^ "Watching the new Epsilon variant of SARS-CoV-2". Healthcare Purchasing News. July 12, 2021. Retrieved September 12, 2021.

According to GISAID, 45 countries, from US to South Korea, from India to Japan have reported Epsilon variant cases.

- ^ Zimmer, Carl; Mandavilli, Apoorva (May 14, 2021). "How the United States Beat the Variants, for Now". New York Times. Archived from the original on December 28, 2021. Retrieved May 17, 2021.

- ^ "GISAID - hCov19 Variants". www.gisaid.org. Retrieved July 2, 2021.

![Amino acid mutations of SARS-CoV-2 Epsilon variant plotted on a genome map of SARS-CoV-2 with a focus on the spike.[7]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/2a/SARS-CoV-2_Epsilon_variant.svg/4043px-SARS-CoV-2_Epsilon_variant.svg.png)