United Nations Ocean Conference

| The United Nations Ocean Conference | |

|---|---|

| |

| Begins | 5 June 2017 |

| Ends | 9 June 2017 |

| Location(s) | UN HQ, New York, United States |

| Website | oceanconference.un.org/ |

The 2017 United Nations Ocean Conference was a United Nations conference that took place on 5-9 June 2017 which sought to mobilize action for the conservation and sustainable use of the oceans, seas and marine resources.[1][2][3]

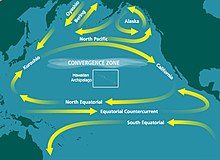

The Earth's waters are said to be "under threat as never before", with pollution, overfishing, and the effects of climate change severely damaging the health of our oceans. For instance as oceans are warming and becoming more acidic, biodiversity is becoming reduced and changing currents will cause more frequent storms and droughts.[4][5][6][7][8] Every year around 8 million metric tons of plastic waste leak into the ocean and make it into the circular ocean currents. This causes contamination of sediments at the sea-bottom and causes plastic waste to be embedded in the aquatic food chain.[9] It could lead to oceans containing more plastics than fish by 2050 if nothing is done.[10][11][12] Key habitats such as coral reefs are at risk and noise pollution are a threat to whales, dolphins, and other species.[13][14][15] Furthermore almost 90 percent of fish stocks are overfished or fully exploited which cost more than $80 billion a year in lost revenues.[16]

UN Secretary-General António Guterres stated that decisive, coordinated global action can solve the problems created by humanity.[4] Peter Thomson, President of the UN General Assembly, highlighted the conference's significance, saying "if we want a secure future for our species on this planet, we have to act now on the health of the ocean and on climate change".[4][2]

The conference sought to find ways and urge for the implementation of Sustainable Development Goal 14.[4] Its theme is "Our oceans, our future: partnering for the implementation of Sustainable Development Goal 14".[20] It also asked governments, UN bodies, and civil society groups to make voluntary commitments for action to improve the health of the oceans with over 1,000 commitments − such as on managing protected areas − being made.[21][22][23]

Since 2014, the UN Ocean Conference and Our Ocean Conference have gathered over 2,160 financial and other quantifiable pledges, mobilising more than $130 billion.[24]

Participation

[edit]Participants include heads of State and Government, civil society representatives, business people, actors, academics and scientists and ocean and marine life advocates from around[quantify] 200 countries.[25][21][26][27][28] Around 6,000 leaders gathered for the conference over the course of the week.[29][30][31]

The Governments of Fiji and Sweden had the co-hosting responsibilities of the Conference.[1][2][32][33][34][35]

7 partnership dialogues with a rich state-developed state theme were co-chaired by Australia-Kenya, Iceland-Peru, Canada-Senegal, Estonia-Grenada, Italy-Palau, Monaco-Mozambique and Norway-Indonesia.[36][37]

Ministers from small island states such as Palau, Fiji and Tuvalu pleaded for help as for them the issue is existential not just on the long-term.[38][39][40]

Outcomes

[edit]Over 1,300 voluntary commitments have been made which UN Under-Secretary-General for Economic and Social Affairs Wu Hongbo called "truly impressive" and stated that they now comprise "an ocean solution registry" via the public online platform.[29][41] 44 percent of the commitments came from governments, 19 percent from NGOs, 9 percent from UN entities and 6 percent from the private sector.[42]

Delegates from China, Thailand, Indonesia and the Philippines pledged to work to keep plastics out of the seas.[43] The Maldives announced a phase out of its non-biodegradable plastic and Austria pledged to reduce the number of plastic bags used per person to 25 a year by 2019.[44]

Several nations announced plans for new marine protected areas. China plans to establish 10 to 20 "demonstration zones" by 2020 and introduced a regulation which requires that 35 percent of the country's shoreline should be natural by 2020.[45] Gabon announced that it will create one of Africa's largest marine protected areas with around 53,000 square kilometres of ocean when combined with its existing zones.[46][11][47] New Zealand affirmed the government's commitment to establishing the Kermadec/Rangitahua Ocean Sanctuary, which − with 620,000 square kilometres − would be one of the world's largest fully protected areas.[48][49][50] Pakistan also announced its first marine protected area.[51]

The US-based international wildlife organisation Wildlife Conservation Society created the MPA Fund in 2016 as well as the blue moon fund for a combined $15 million commitment which aims to create 3.7 million square kilometers of new marine protected areas with The Tiffany & Co. Foundation adding a $1 million grant toward this fund in the week of the conference.[52] Germany's Federal Minister for the Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety Barbara Hendricks also pledged to allocate €670 million for marine conservation projects and made 11 voluntary commitments.[53][54]

Deputy Director-General of the State Oceanic Administrations Lin Shanqing of China − the world's main fish producer and exporter[16] − stated that the country would be "willing, based on its own development experience, to work actively for the establishment in the area of the ocean of an open, inclusive, concrete, pragmatic, mutually beneficial and win-win blue partnership with other countries and international organizations".[55]

The conference ended with the adoption by consensus of a 14-point Call for Action by the 193 UN member states in which they affirmed their "strong commitment to conserve and sustainably use our oceans, seas and marine resources tor sustainable development".[56][29][57][58][31] With this call, the Ocean Conference also sought to raise global awareness of ocean problems.[41]

Private sector

[edit]On 9 June an official side event of the United Nations Ocean Conference for addressing ways by which the private sector provides practical solutions to address the problems such as by improving energy efficiency, waste management[59] and introducing market-based tools to shift investment, subsidy and production.[60]

Nine of the world's biggest fishing companies from Asia, Europe and the US have signed up for The Seafood Business for Ocean Stewardship (SeaBOS) initiative, supported by the Stockholm Resilience Centre, aiming to end unsustainable practices.[61]

Research and technology projects

[edit]At the conference Indonesia published its vessel monitoring system (VMS) publicly revealing the location and activity of its commercial fishing boats on the Global Fishing Watch public mapping platform.[62] Brian Sullivan states that the platform is can easily incorporate additional data sources which may allow "mov[ing] from raw data to quickly producing dynamic visualizations and reporting that promote scientific discovery and support policies for better fishery management".[62]

Irina Bokova of UNESCO notes that "we cannot manage what we cannot measure, and no single country is able to measure the myriad changes taking place in the ocean", and asks for more maritime research and the sharing of knowledge to craft common science-based policies.[23]

Peru co-chaired the "Partnership Dialogue 6 – Increasing scientific knowledge, and developing research capacity and transfer of marine technology" with Iceland.[63]

On 7 June researchers at the Dutch The Ocean Cleanup foundation published a study according to which rivers − such as the Yangtze − carry an around 1.15–2.41 million tonnes of plastic into the sea every year.[12][64][65][66]

Obstacles to implementation

[edit]

UN Secretary-General António Guterres warned that unless nations overcome short-term territorial and resource interests the state of the oceans will continue to deteriorate. He also names "the artificial dichotomy" between jobs and healthy oceans as one of the main challenges and asks for strong political leadership, new partnerships and concrete steps.[25][67][68][69][70][11]

Deputy Secretary-General of the United Nations Amina J Mohammed warns about the harm of overlooking the climate concerns in turn for perceived "national gain", claiming that "a moral obligation to the world which [one] live[s] on" exists.[71]

India, attended indirectly via two non-governmental organisations[27] until 9 June when Minister of State for External Affairs M J Akbar told the conference that the negative impact of overfishing, habitat destruction, pollution and climate change are becoming increasingly clear and that the time for action would be "already long overdue".[72][73]

Bolivia's President Evo Morales told the conference that, one of the world's main polluters, the United States denied science, turned its backs on multilateralism, and attempted to deny a future to upcoming generations by its national government deciding to leave the Paris agreement, making "it the main threat to Mother Earth and life itself".[21][74][11][47][71] Albert II, Prince of Monaco called Trump's withdrawal "catastrophic" and the reaction from US mayors, governors and many in the corporate world as "wonderful".[75] On 30 May Sweden's deputy prime minister Isabella Lövin stated that the United States is resisting plans to highlight how climate change is disrupting life in the oceans at the conference, that the US has negatively affected preparations and that "the decline of the oceans is really a threat to the entire planet" with a "need to start working together".[76][77] Lövin also makes note of difficulties to engage with Washington in the conference, partly because key posts at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration remain unfilled since the end of the Obama administration.[76]

UNCTAD Secretary-General Mukhisa Kituyi states that subsidies from wealthy governments encourage overfishing, overcapacity and may contribute to illegal and unregulated fishing, creating food insecurity, unemployment and poverty for people relying mainly on fish as their primary source of nourishment or livelihood.[78]

Impact and progress

[edit]Marine biologist Ayana Elizabeth Johnson notes that the UN's work alone is not nearly enough and that for a solution to this existential crisis of the health of our global environment, strong and inspired leadership at all levels – from mayors, to governors, CEOs, scientists, artists and presidents is needed.[79]

In 2010 the international community agreed to protect 10% of the ocean by 2020 in the Convention on Biological Diversity's Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011–2020 and Sustainable Development Goal 14.[80][81] However as of June 2017 less than 3% of the ocean are under some form of protection.[82] Pledges made during the conference would add around an additional 4.4 percent of protected marine areas,[58] increasing the protected total to around 7.4% of the ocean. A later study (in 2018), reveals that 3,6% was protected.[83][84]

Peter Thomson called the conference was a success, stating that he was "satisfied with [its] results", that the conference "held at a very critical time" has "turned the tide on marine pollution". He says that "we are now working around the world to restore a relationship of balance and respect towards the ocean".[29][57]

Elizabeth Wilson, director of international conservation at Pew Charitable Trusts thinks that this meeting "will be followed by a whole series of other meetings that we hope will be impacted in a positive way".[85]

The next conference was scheduled for 2020,[86][87][41] but postponed due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[88] Portugal's Minister for the Seas, Ana Paula Vitorino stated that Lisbon would like to host the next event in 2020.[86] Kenya's Foreign Affairs Cabinet Secretary Amina Mohamed also offered for Kenya to host the next event.[41][89]

Culture and society

[edit]The event coincided with the World Oceans Day on 8 June and started with the World Environment Day on 5 June.[1][90][63][91][92]

On 4 June the World Ocean Festival took place at New York City's Governors Island. The festival was hosted by the City of New York, organized by the Global Brain Foundation and was free and open to the public.[93][94][95]

China announced a new international sailing competition and Noahs Sailing Club press officer Rebecca Wang stated that "sailing allows for a better appreciation of the ocean and the natural environment. Many wealthy Chinese think of luxury yachts when they think of maritime sports, and we're trying to foster a maritime culture that's more attuned to the environment".[96]

Users of social media worldwide use the hashtag #SaveOurOcean for discussion, information and media related to the conference and its goals.[97][98] The #CleanSeas cyber campaign calls on governments, industry and citizens to end excessive, wasteful usage of single-use plastic and eliminate microplastics in cosmetics with its petition getting signed by more than 1 million people.[99][100][101][102]

See also

[edit]- United Nations-Oceans

- United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development

- National interest

- Collective problem solving

- Global catastrophic risk

- March for Science

- Global change

- Spaceship Earth

- World community

- Global citizenship

- Sustainability and environmental management § Oceans

- Ocean governance

- Resource management

References

[edit]- ^ a b c "The Ocean Conference | 5–9 June 2017". United Nations. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- ^ a b c "UN Ocean Conference 2017 Seeks To Avoid Climate Change Catastrophe". International Business Times. 6 June 2017. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- ^ "Erste UN-Ozeankonferenz hat begonnen" (in German). Tagesschau. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- ^ a b c d Frangoul, Anmar (6 June 2017). "UN Secretary General Guterres says world's oceans are facing unprecedented threat". CNBC. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- ^ "UN chief calls for coordinated global action to solve ocean problems". Xinhua News Agency. Archived from the original on 5 June 2017. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- ^ "West Coast states encourage worldwide fight against ocean acidification". Governor Inslee's Communications Office. Retrieved 10 June 2017.

- ^ "Save our Oceans – The Manila Times Online". Manila Times. 4 June 2017. Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- ^ "Klimawandel – Ozeankonferenz warnt vor Versauerung der Meere". Deutschlandfunk (in German). Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- ^ "California models how to clean up, reduce, recycle plastic waste". San Francisco Chronicle. 7 June 2017. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- ^ Wearden, Graeme (19 January 2016). "More plastic than fish in the sea by 2050, says Ellen MacArthur". The Guardian. Retrieved 8 June 2017.

- ^ a b c d "UN chief warns oceans are 'under threat as never before'". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 5 June 2017. Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- ^ a b "Plastic in rivers major source of ocean pollution: study". Retrieved 8 June 2017.

- ^ "At the UN Ocean Conference, Recognizing an Unseen Pollutant: Noise". National Geographic Society (blogs). 8 June 2017. Archived from the original on 8 June 2017. Retrieved 8 June 2017.

- ^ "Recommendations for addressing Ocean Noise Pollution: A joint statement to the Oceans Conference" (PDF). Retrieved 8 June 2017.

- ^ Lind, Fredrik; Tanzer, John (7 June 2017). "Make or break moment for the oceans". CNN. Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- ^ a b c "FACTBOX-12 facts as World Oceans Day puts spotlight on climate change, pollution, overfishing". Reuters UK. 8 June 2017. Retrieved 8 June 2017.

- ^ Jain, Sharad K.; Agarwal, Pushpendra K.; Singh, Vijay P. (2007). Hydrology and Water Resources of India. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9781402051807. Retrieved 8 June 2017.

- ^ Kalman, Bobbie (2008). Earth's Coasts. Crabtree Publishing Company. p. 4. ISBN 9780778732068. Retrieved 8 June 2017.

- ^ Leith, James A.; Price, Raymond A.; Spencer, John Hedley (1995). Planet Earth: Problems and Prospects. McGill-Queen's Press – MQUP. ISBN 9780773512924. Retrieved 8 June 2017.

- ^ "Ghana: UN Begins Ocean Conference to Stop the Sea Pollution". Government of Ghana (Accra). 6 June 2017. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- ^ a b c "UN chief warns oceans 'under threat as never before'". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- ^ "UN News – At Ocean Conference, UN agencies commit to cutting harmful fishing subsidies". 6 June 2017. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- ^ a b "UN marks World Oceans Day at Ocean Conference". Xinhua News Agency. Archived from the original on 9 June 2017. Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- ^ "Ocean economy offers a $2.5 trillion export opportunity: UNCTAD report | UNCTAD". unctad.org. 26 October 2021. Retrieved 23 February 2023.

- ^ a b "UN Ocean Conference opens with calls for united action to reverse human damage". UN News Centre. 5 June 2017. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- ^ "KUNA : Ocean Conf. kicks off activities, calls for accelerated action". kuna.net.kw. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- ^ a b "City-based NGO to attend ocean meet". The Hindu. 4 June 2017. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- ^ Worland, Justin; Lull, Julia. "Marine Biologist Has a Message for Climate Change Deniers". Time. Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- ^ a b c d "UN News – UN Ocean Conference wraps up with actions to restore ocean health, protect marine life". UN News Service Section. 9 June 2017. Retrieved 10 June 2017.

- ^ "With focus on natural disasters, UN risk reduction forum opens in Mexico". Indiablooms. Retrieved 10 June 2017.

- ^ a b "Pakistan vows to back steps to improve world's oceans' health". The Nation. 11 June 2017. Retrieved 11 June 2017.

- ^ Conduit, Rox. "UN Oceans Conference begins today". fbc.com.fj. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- ^ "PM: We're Ready, Expect The Best This Week". Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- ^ "Prime Minister of Sri Lanka addresses UN ocean conference". Lanka Business Online. 6 June 2017. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- ^ "To save our oceans". Fiji Times. Retrieved 11 June 2017.

- ^ Sood, Vrinda. "Will the US Play a Role at the UN Oceans Forum This June?". The Wire. Retrieved 11 June 2017.

- ^ "14 Governments Appointed Co-Chairs of Ocean Dialogues". IISD's SDG Knowledge Hub. Retrieved 11 June 2017.

- ^ Roth, Richard (7 June 2017). "At first UN Ocean Conference, island nations plead for help". CNN. Retrieved 8 June 2017.

- ^ "Kommentar: Wieviel Dummheit verträgt ein Ozean?" (in German). Tagesschau. Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- ^ Simmons, Ann M. (15 November 2016). "One looming consequence of climate change: Small island nations will cease to exist". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- ^ a b c d "Ocean Conference Strikes More Than 1k Commitments". Fiji Sun. Retrieved 11 June 2017.

- ^ "Vital action". Fiji Times. Retrieved 11 June 2017.

- ^ Harrabin, Roger (8 June 2017). "Asian nations make plastic oceans promise". BBC News. Retrieved 8 June 2017.

- ^ "Experts tell Trump: 'Don't forget the oceans'". Sky News. Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- ^ "China supports marine-friendly 'blue economy'". ecns.cn. Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- ^ "Gabon to create one of Africa's largest marine protected areas". The Independent. 5 June 2017. Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- ^ a b Lederer, Edith M. "More plastic than fish? Oceans 'under threat as never before,' warns UN chief". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- ^ "NZ commits to protecting and conserving ocean". Radio New Zealand. 10 June 2017. Retrieved 10 June 2017.

- ^ "Govt urged to walk the talk on dolphins, oceans". Radio New Zealand. 11 June 2017. Retrieved 10 June 2017.

- ^ "Kermadec ocean sanctuary named – but no compensation". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 10 June 2017.

- ^ "Is the tide turning for oceans?". Thomson Reuters Foundation. Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- ^ Samper, Cristián (9 June 2017). "It Will Take the World Community to Save the World's Ocean". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- ^ "Hendricks wirbt bei UNO für internationale Anstrengungen beim Meeresschutz". Stern (in German). 9 June 2017. Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- ^ "Hendricks wirbt bei UNO für internationale Anstrengungen beim Meeresschutz" (in German). Wochenblatt. Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- ^ "China calls for enhancing equality, mutual trust in global ocean governance". Xinhua News Agency. Archived from the original on 8 June 2017. Retrieved 8 June 2017.

- ^ "Meereskonferenz: Uno-Mitgliedstaaten verabreden Schutz der Ozeane". Der Spiegel. 9 June 2017. Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- ^ a b "Five-day UN Ocean Conference concludes with Call to Action". Xinhua News Agency. Archived from the original on 10 June 2017. Retrieved 10 June 2017.

- ^ a b "193 UN member nations urge action to protect oceans, US backs call". The Indian Express. 10 June 2017. Retrieved 10 June 2017.

- ^ "UN-Ozeankonferenz: Ohne Blau kein Grün auf unserer Erde – heute-Nachrichten" (in German). heute (ZDF). Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- ^ "UN Oceans Conference side-event showcases private sector solutions to worsening climate impacts – ICC – International Chamber of Commerce". ICC – International Chamber of Commerce. 7 June 2017. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- ^ Harvey, Fiona (9 June 2017). "Nine of world's biggest fishing firms sign up to protect oceans". The Guardian. Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- ^ a b "Indonesia makes its fishing fleet visible to the world through Global Fishing Watch". Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- ^ a b "Production Ministry leads Peru delegation at UN Ocean Conference" (in Spanish). andina.com.pe. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- ^ "Plastic in rivers major source of ocean pollution: study". The Nation. 9 June 2017. Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- ^ "Most ocean plastic comes from Asian rivers: study". Japan Times. 9 June 2017. Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- ^ "Plastics remain the major source of ocean pollution – Kuwait Times". Kuwait Times. 11 June 2017. Retrieved 11 June 2017.

- ^ "Conserving our oceans and using them sustainably is preserving life itself". News.com.au. 6 June 2017. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- ^ Braune, Gerd (6 June 2017). "Mehr Plastik als Plankton". Der Tagesspiegel (in German). Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- ^ "UN calls on world to save our oceans". euronews. 5 June 2017. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- ^ "UN Ocean meet calls for united action". The Hindu. 7 June 2017. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- ^ a b Timmis, Anna. "UN Officials React to Trump's Paris Decision at Ocean Conference". Townhall. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- ^ "Don't turn seas into areas of conflict, says MJ Akbar at United Nations Ocean Conference". Firstpost. 9 June 2017. Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- ^ "Do Not Turn Seas into Areas of Conflict: MJ Akbar". NDTV. Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- ^ Papenfuss, Mary (6 June 2017). "U.S. Lashed As 'Main Threat' To Environment at UN Ocean Conference". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- ^ "Monaco's ruler: Trump should listen to scientists on climate". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 8 June 2017. Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- ^ a b "INTERVIEW-US resists plan to link climate change, ocean health-UN co-chair". Thomson Reuters Foundation. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- ^ "U.S. resists plan to link climate change, ocean health: U.N. co-chair". Business Insider. Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- ^ "UNCTAD and other global influencers gather to discuss eliminating harmful fisheries subsidies at UN Ocean Conference". 6 June 2017. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- ^ Johnson, Ayana Elizabeth (2 June 2017). "Climate, Oceans, the United Nations, and What's Next". National Geographic Society (blogs). Archived from the original on 2 June 2017. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- ^ "Marine Protected Areas and climate change" (PDF). Retrieved 10 June 2017.

- ^ "Global marine protected are a target of 10% to be achieved by 2020" (PDF). Retrieved 10 June 2017.

- ^ Mittler, Daniel (7 June 2017). "Time for ocean action – for us, our climate and diversity on earth". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- ^ The World Has Two Years to Meet Marine Protection Goal. Can It Be Done?

- ^ Sala, Enric; Lubchenco, Jane; Grorud-Colvert, Kirsten; Novelli, Catherine; Roberts, Callum; Sumaila, U. Rashid (2018). "Assessing real progress towards effective ocean protection". Marine Policy. 91: 11–13. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2018.02.004.

- ^ "'We cannot afford to fail': Pacific leaders appeal for action on World Oceans Day". ABC News. 8 June 2017. Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- ^ a b "Portugal wants next UN Ocean Conference". Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- ^ Hostert, Alexandra (9 June 2017). "The Ocean Conference – Absehbar oder enttäuschend?" (in German). WDR. Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- ^ "2020 UN Ocean Conference Postponed". New York: United Nations. 15 April 2020. Retrieved 11 July 2022.

- ^ "Kenya submits AG Muigai as candidate for UN sea law organ". The Star, Kenya. Retrieved 11 June 2017.

- ^ Chhotray, Shilpi (5 June 2017). "Kicking Off The United Nations Ocean Conference". National Geographic Society (blogs). Archived from the original on 5 June 2017. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- ^ "Local Chapter Headed to Ocean Conference at U.N. Headquarters – Times of San Diego". Times of San Diego. 3 June 2017. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- ^ Besheer, Margaret. "Pollution Slowly Killing Planet's Ocean". VOA. Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- ^ "UN announces first-ever World Ocean Festival". United Nations Sustainable Development. 11 April 2017. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- ^ "Thomson To Welcome RFMF Band". Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- ^ Nicholls, Sebastian (3 May 2017). "Celebrating a Living Ocean of Wonder". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- ^ "Chinese club unveils open-ocean yacht race plan". South China Morning Post. 10 June 2017. Retrieved 10 June 2017.

- ^ Neill, Peter (16 May 2017). "United Nations Ocean Conference: Our Ocean, Our Future". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- ^ "Committed to the Ocean: The First United Nations Ocean Conference". Nature Conservancy Global Solutions. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- ^ "Over 1 million people demand global ban on single-use plastic at UN Ocean Conference". Xinhua News Agency. Archived from the original on 7 June 2017. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- ^ "Plastic is not fantastic: time to curb its use". The Irish Times. Retrieved 8 June 2017.

- ^ "Ozeane – Heimat für Korallen und Plastikmüll" (in German). Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 8 June 2017.

- ^ "British billionaire delivers 1 mln signatures urging governments to protect ocean". Xinhua News Agency. Archived from the original on 14 June 2017. Retrieved 8 June 2017.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- #OceanConference on Twitter

- United Nations – LIVE – UN Ocean Conference, recording of the livestreamed conference on YouTube