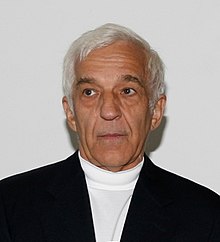

Vladimir Ashkenazy

Vladimir Davidovich Ashkenazy (Russian: Влади́мир Дави́дович Ашкена́зи, Vladimir Davidovich Ashkenazi; born 6 July 1937) is a Russian solo pianist, chamber music performer, and conductor. Born in the Soviet Union, he has held Icelandic citizenship since 1972 and has been a resident of Switzerland since 1978. Ashkenazy has collaborated with well-known orchestras and soloists. In addition, he has recorded a large repertoire of classical and romantic works. His recordings have earned him five Grammy awards and Iceland's Order of the Falcon.

Early life

[edit]Vladimir Ashkenazy was born in Gorky, Soviet Union (now Nizhny Novgorod, Russia), to pianist and composer David Ashkenazi and to actress Yevstolia Grigorievna (born Plotnova). His father was Jewish and his mother came from a Russian Orthodox family. Ashkenazy was christened in a Russian Orthodox church.[1][2][3] He began playing piano at the age of six and was accepted to the Central Music School at age eight, studying with Anaida Sumbatyan.

Education

[edit]Ashkenazy attended the Moscow Conservatory where he studied with Lev Oborin and Boris Zemliansky. He won second prize in the V International Chopin Piano Competition in Warsaw in 1955 and the first prize in the Queen Elisabeth Music Competition in Brussels in 1956. He shared the first prize in the 1962 International Tchaikovsky Competition with British pianist John Ogdon. As a student, like many in that period, he was harassed by the KGB to become an "informer".[4]

Personal life

[edit]

In 1961, he married the Iceland-born Þórunn Jóhannsdóttir, who studied piano at the Moscow Conservatory.[1] To marry Ashkenazy, Þórunn was forced to give up her Icelandic citizenship and declare that she wanted to live in the USSR. Her name is usually transliterated as "Thorunn"; her nickname is Dódý,[5] so she is called Dódý Ashkenazy.[6]

After numerous bureaucratic procedures, the Soviet authorities agreed to allow the Ashkenazys to visit the West for musical performances and for visits to his parents-in-law with their first grandson. In his memoirs, Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev recollected that Ashkenazy on a visit to London had refused to return to the Soviet Union. Khrushchev mentioned that Ashkenazy then sought advice from the Soviet Embassy in London, who in turn referred the matter to Moscow. Khrushchev said he was of the opinion that to require Ashkenazy to return to the USSR would have made him an "Anti-Soviet". He further said that this was a good example of an artist being able to come and go in and out of the USSR freely, which Ashkenazy said was a gross "distortion of the truth".[clarification needed][7] In 1963, Ashkenazy decided to leave the USSR permanently, establishing residence in London, where his wife's parents lived.

The couple moved to Iceland in 1968 where, in 1972, Ashkenazy became an Icelandic citizen.[8] In 1970 he helped to found the Reykjavík Arts Festival, of which he remains Honorary President.[9][10] In 1978 the couple and their (then) four children (Vladimir Stefan, Nadia Liza, Dimitri Thor, and Sonia Edda) moved to Lucerne, Switzerland. Their fifth child, Alexandra Inga, was born in 1979. Beginning in 1989, Ashkenazy resided in Meggen, Switzerland, on Lake Lucerne.[11] His eldest son Vladimir, who uses his nickname 'Vovka' as a stage name, is a pianist, as well as a teacher at the Imola International Piano Academy. His second son, Dimitri, is a clarinetist.

Critical reception

[edit]The Guardian wrote in 2018 that Ashkenazy conducted pieces by Prokofiev and Glière as if he had been "born to do it" during a concert series that explored the musical response to the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, including composer Alexander Mosolov's Iron Foundry (1927) and the suite from The Red Poppy, a ballet with music by Glière.[12]

Career

[edit]| External audio | |

|---|---|

Études Op. 10 Études Op. 25 Nocturne in B major, Op. 9, No. 3 Ballade No. 2 and Franz Liszt's Mephisto Waltz No. 1 in 1960 here on archive.org |

Ashkenazy has recorded a wide range of piano repertoire, both solo works and concerti. His recordings include:

- Bach's The Well-Tempered Clavier

- Bach's French Suites

- 24 Preludes and Fugues of Shostakovich

- complete sonatas by Beethoven

- complete sonatas by Scriabin

- the complete works for piano by Rachmaninoff

- the complete works for solo piano by Chopin

- the (almost) complete works for piano by Schumann

His concerto recordings include:

- the complete piano concertos of Mozart (conducting from the keyboard with the Philharmonia Orchestra)

- three cycles of the 5 Beethoven concerti

- (a) with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra under Sir Georg Solti

- (b) with Zubin Mehta and the Vienna Philharmonic

- (c) conducting from the piano with the Cleveland Orchestra

- Brahms with Bernard Haitink (No. 1 with the Concertgebouw Orchestra; No. 2 with the Vienna Philharmonic)

- Bartók (with Georg Solti and the London Philharmonic Orchestra)

- Prokofiev (with André Previn and the London Symphony Orchestra)

- two cycles of the Rachmaninoff concerti

- (a) with André Previn and the London Symphony Orchestra

- (b) with Bernard Haitink and the Concertgebouw Orchestra

In public piano performances, Ashkenazy was known for rejecting a tie and button shirt in favor of a white turtleneck and for running (not walking) onstage and offstage. He has also performed and recorded chamber music. Moreover, Ashkenazy has had an acclaimed collaborative career, including an acclaimed recording of Beethoven's complete violin sonatas with Itzhak Perlman, as well as the cello sonatas with Lynn Harrell, and the piano trios with Harrell and Perlman.

Midway through his international pianistic career, Ashkenazy branched into conducting. In Europe, Ashkenazy was principal conductor of the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra from 1987 to 1994, and of the Czech Philharmonic from 1998 to 2003. Ashkenazy is also conductor laureate of the Philharmonia Orchestra, conductor laureate of the Iceland Symphony Orchestra, and music director of the European Union Youth Orchestra.[13] In July 2013 he became director of the Accademia Pianistica Internazionale di Imola, succeeding its founder and director Franco Scala.[14] His recordings as a conductor include complete cycles of the symphonies of Sibelius and of Rachmaninoff, as well as orchestral works of Prokofiev, Shostakovich, Scriabin, Richard Strauss, Stravinsky, Beethoven, and Tchaikovsky.

Outside of Europe, Ashkenazy served as music director of the NHK Symphony Orchestra from 2004 to 2007. He was chief conductor of the Sydney Symphony Orchestra from 2009 to 2013.[15]

Ashkenazy has recorded for Decca since 1963; in 2013, Decca celebrated his 50th anniversary with the label with the box set 'Vladimir Ashkenazy: 50 Years on Decca', including 50 of Ashkenazy's recordings as both pianist and conductor.[16] As part of Ashkenazy's 80th birthday celebrations, Decca is releasing the 'Complete Piano Concerto Recordings' and 'Ashkenazy on Vinyl' in July 2017. In other media, Ashkenazy has also appeared in several films on music by Christopher Nupen. He interpreted the soundtrack of the film Piano Forest: works from the repertoire of Bach, Mozart, Chopin and Beethoven. He has also made his own orchestration of Modest Mussorgsky's piano suite Pictures at an Exhibition (1982). There has been a CD produced of his works named 'The Art of Ashkenazy', and a biography of Ashkenazy, 'Beyond Frontiers', has been published.

On 17 January 2020 the artist management agency Harrison Parrott announced Ashkenazy's retirement from public performance.[17]

Awards and recognition

[edit]- 1955 V International Chopin Piano Competition, Warsaw (Second prize)[18]

- 1956 Queen Elisabeth Music Competition for piano, Brussels

- 1962 International Tchaikovsky Competition, Moscow (shared with John Ogdon)

- 2000 Hanno R. Ellenbogen Citizenship Award, with the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra conducting corps

- Current president of the Rachmaninoff Society.

- Elgar Medal, 2019[19]

- 2014 Sergei Rachmaninov International Award

- 1974 Beethoven: The Piano Concertos (Vladimir Ashkenazy, Sir Georg Solti & Chicago Symphony Orchestra)

- 1979 Beethoven: Sonatas for Violin and Piano (Itzhak Perlman & Vladimir Ashkenazy)

- 1982 Tchaikovsky: Piano Trio in A minor (Vladimir Ashkenazy, Itzhak Perlman, Lynn Harrell)

- 1988 Beethoven: The Complete Piano Trios (Vladimir Ashkenazy, Itzhak Perlman, Lynn Harrell)

- 1986 Ravel: Gaspard de la nuit; Pavane pour une infante défunte; Valses nobles et sentimentales

- 2000 Shostakovich: 24 Preludes and Fugues, Op. 87

ARIA Music Awards

[edit]The ARIA Music Awards is an annual awards ceremony that recognises excellence, innovation, and achievement across all genres of Australian music. They commenced in 1987.

| Year | Nominee / work | Award | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | Elgar: The Dream of Gerontius (with Sydney Symphony Orchestra) | Best Classical Album | Nominated | [20] |

Bibliography

[edit]- Ashkenazy, Vladimir; Parrott, Jasper (1985). Beyond Frontiers. New York: Atheneum. ISBN 0-689-11505-9.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Ashkenazy – Still Russian to the core, The Independent, 3 October 2008 (retrieved 23 October 2008)

- ^ Iceland Review Online: Daily News from Iceland, Current Affairs, Business, Politics, Sports, Culture. Icelandreview.com (6 December 2005). Retrieved on 2013-08-02.

- ^ Ashkenazy, Vladimir. Enotes.com. Retrieved on 29 October 2013.

- ^ lebrecht, norman (10 August 2009). "Vladimir Ashkenazy: My Life in the KGB". Slippedisc. Retrieved 28 April 2023.

- ^ "Russian Pianist Vladimir Ashkenazy Interviewed". Britishpathe.com. Retrieved 4 January 2019.

- ^ "Rachmaninov: Transcriptions by Alastair Mackie, Dody Ashkenazy, Vladimir Ashkenazy & Vovka Ashkenazy". Itunes.apple.com. January 2002. Retrieved 4 January 2019.

- ^ Khrushchev Remembers, London 1971 p. 521

- ^ Vladimir Ashkenazy. Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ "Organisation — Reykjavík Artfest". Archive.vn. 4 November 2013. Archived from the original on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 4 January 2019.

- ^ European Festivals Association Archived 31 December 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Efa-aef.eu. Retrieved on 29 October 2013.

- ^ Interview with Vladimir Ashkenazy Basler Zeitung, 3 March 2015

- ^ "Philharmonia/Ashkenazy review – thumping Soviet classics pin you to your seat". The Guardian. 25 March 2018. Retrieved 23 July 2019.

- ^ "European Union Youth Orchestra". Archived from the original on 20 April 2008. Retrieved 23 October 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link). European Unions Youth Orchestra. - ^ "Musica: Vladimir Ashkenazy nuovo direttore dell'Accademia pianistica di Imola". La Repubblica (Bologna). 15 July 2013. Retrieved 12 January 2014.

- ^ Joyce Morgan; Paul Bibby (12 April 2007). "Maestro's star power a masterstroke for orchestra". The Sydney Morning Herald. p. 13. Retrieved 12 April 2007.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "VLADIMIR ASHKENAZY 50 Years on Decca". Decca Classics. Retrieved 17 October 2016.

- ^ "VLADIMIR ASHKENAZY RETIRES". Harrison Parrott. 17 January 2020. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- ^ Albert Grudziński (1955). "Competition V". IFCPC Official Site. Archived from the original on 14 April 2007. Retrieved 4 May 2007.

- ^ "Elgar Society Awards". Elgar Society. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- ^ ARIA Award previous winners. "ARIA Awards – Winners by Award". Australian Recording Industry Association (ARIA). Retrieved 9 July 2022.

External links

[edit]- 1937 births

- Living people

- Musicians from Nizhny Novgorod

- 20th-century conductors (music)

- 21st-century conductors (music)

- 20th-century Russian male musicians

- 21st-century Russian male musicians

- Russian classical pianists

- Soviet defectors

- Russian male classical pianists

- Icelandic conductors (music)

- Icelandic expatriates in the United Kingdom

- Grammy Award winners

- Honorary Members of the Royal Academy of Music

- Moscow Conservatory alumni

- Prize-winners of the International Chopin Piano Competition

- Prize-winners of the International Tchaikovsky Competition

- Prize-winners of the Queen Elisabeth Competition

- Recipients of the Order of Merit of Berlin

- Soviet emigrants to Iceland

- Naturalised citizens of Iceland

- Icelandic emigrants to Switzerland

- Musicians from Lucerne

- Jewish classical pianists

- Russian emigrants to Iceland

- Russian emigrants to Switzerland

- Soviet Jews

- Russian Ashkenazi Jews