Fat Man and Little Boy (film)

| Fat Man and Little Boy | |

|---|---|

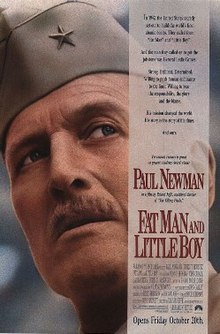

Original poster | |

| Directed by | Roland Joffé |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Story by | Bruce Robinson |

| Produced by | Tony Garnett |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Vilmos Zsigmond |

| Edited by | Françoise Bonnot |

| Music by | Ennio Morricone |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 127 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $30 million[1] |

| Box office | $3,563,162 |

Fat Man and Little Boy (released in the United Kingdom as Shadow Makers) is a 1989 American epic historical war drama film directed by Roland Joffé, who co-wrote the script with Bruce Robinson. The story follows the Manhattan Project, the secret Allied endeavor to develop the first nuclear weapons during World War II. The film is named after "Little Boy" and "Fat Man", the two bombs dropped on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, respectively.

Plot

[edit]In September 1942, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Colonel Leslie Groves, who oversaw the construction of the Pentagon, is assigned to head the ultra-secret Manhattan Project, to beat the Germans, who have a similar nuclear weapons program.

Groves picks University of California, Berkeley, physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer to head the project team. Oppenheimer was familiar with northern New Mexico from his boyhood days when his family owned a cabin in the area. For the new research facility, he selects a remote location on top of a mesa adjacent to a valley called Los Alamos Canyon, northwest of Santa Fe.

The different personalities of the military man Groves and the scientist Oppenheimer often clash in keeping the project on track. Oppenheimer in turn clashes with the other scientists, who debate whether their personal consciences should enter into the project or whether they should remain purely researchers, with personal feelings set aside.

Nurse Kathleen Robinson and young physicist Michael Merriman question what they are doing. Working with little protection from radiation during an experiment, Michael drops a radioactive component during an experiment dubbed Tickling the Dragon's Tail and retrieves it by hand to avoid disaster, but is exposed to a lethal dose of radiation. In the base hospital, nurse Kathleen can only watch as he develops massive swelling and deformation before dying a miserable death days later.

While the technical problems are being solved, investigations are undertaken to thwart foreign espionage, especially from communist sympathizers who might be associated with socialist organizations. The snooping reveals that Oppenheimer has had a young mistress, Jean Tatlock, and he is ordered by Groves to stop seeing her. After he breaks off their relationship without being able to reveal the reasons why, she is unable to cope with the heartache and is later found dead, apparently a suicide.

As the project continues in multiple sites across America, technical problems and delays cause tensions and strife. To avoid a single point of failure plan, two separate bomb designs are implemented: a large, heavy plutonium bomb imploded using shaped charges ("Fat Man"), and an alternative design for a thin, less heavy uranium bomb triggered in a shotgun or gun-type design ("Little Boy"). The bomb development culminates in a detonation in south-central New Mexico at the Trinity Site in the Alamogordo Desert (05:29:45 on July 16, 1945), where everyone watched in awe at the spectacle of the first mushroom cloud with roaring winds, even miles away. Both bombs, Fat Man and Little Boy, were successful, ushering in the Atomic Age.

Cast

[edit]- Paul Newman as General Leslie Groves

- Dwight Schultz as J. Robert Oppenheimer

- Bonnie Bedelia as Kitty Oppenheimer

- John Cusack as Michael Merriman

- Laura Dern as Kathleen Robinson

- Ron Frazier as Peer de Silva

- Fred Thompson as Maj. Gen. Melrose Hayden Barry

- John C. McGinley as Capt. Richard Schoenfield, MD

- Natasha Richardson as Jean Tatlock

- Ron Vawter as Jamie Latrobe

- Michael Brockman as William Sterling Parsons

- Del Close as Dr. Kenneth Whiteside

- John Considine as Robert Tuckson

- Allan Corduner as Franz Goethe

- Todd Field as Robert R. Wilson

- Ed Lauter as Whitney Ashbridge

- Franco Cutietta as Enrico Fermi

- Joe D'Angerio as Seth Neddermeyer

- Jon DeVries as Johnny Mount

- Gerald Hiken as Leo Szilard

- Barry Yourgrau as Edward Teller

- James Eckhouse as Robert Harper

- Mary Pat Gleason as Dora Welsh

- Clark Gregg as Douglas Panton

- Péter Halász as George Kistiakowsky

- Robert Peter Gale as Dr. Louis Hempelemann

- Krzysztof Pieczyński as Otto Robert Frisch

Basis

[edit]Most of the characters were real people and most of the events were real happenings, with some theatrical license used in the film.

The character of Michael Merriman (John Cusack) is a fictional composite of several people and is put into the film to provide a moral compass as the "common man".[2] Part of the character is loosely based on the scientist Louis Slotin.[3] Contrary to Merriman's death in the movie, Slotin's accident and death occurred after the dropping of the two bombs on Japan, and his early death was feared by some as karma after the event.[4] A very similar mishap happened less than two weeks after the Nagasaki bomb, claiming the life of Harry Daghlian. Both incidents occurred with the same plutonium core, which became known as the demon core.

Even before Oppenheimer was chosen to be the lead scientist of the Manhattan Project, he was under surveillance by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) due to suspected Communist views.[5] Once selected, the surveillance was constant: every single phone call was recorded and every contact with another person was noted. After he was picked to head the laboratory, he met with Tatlock only one time, in mid-June 1943, where she told him that she still loved him and wanted to be with him.[6] After spending that night together, he never saw her again. She died by suicide six months after their meeting.[7]

Production

[edit]The filming took place in the fall of 1988 mainly outside Durango, Mexico, where the Los Alamos research facility was re-created. The re-creation of the Los Alamos laboratory entailed 35 buildings and cost over $2 million to construct in 1988.[8]

Soundtrack

[edit]The film includes a musical score by long-time composer Ennio Morricone. The entire score and extra music were released in 2011, by La La Land Records. The two-CD release has source cues, portions of others, and alternate takes that were dropped from the final cut of the film. Produced by Dan Goldwasser and mastered by Mike Matessino. The CD includes liner notes by film music writer Daniel Schweiger. Only 3,000 copies were released.[citation needed]

Reception

[edit]The film has been criticized for distortion of history for dramatic effect, and miscasting in its choices of Paul Newman for the role of General Groves, and Dwight Schultz for the role of Oppenheimer. Noted critic Roger Ebert felt the film lackluster, giving it 1½ stars, saying, "The story of the birth of the bomb is one of high drama, but it was largely intellectual drama, as the scientists asked themselves, in conversations and nightmares, what terror they were unleashing on the Earth. Fat Man and Little Boy reduces their debates to the childish level of Hollywood stereotyping."[9] The film holds a 50% rating on review aggregate Rotten Tomatoes based on 24 reviews.[10]

The film made under $4 million on its original release. It entered the 40th Berlin International Film Festival.[11]

See also

[edit]- The Beginning or the End, 1947 docudrama film

- Day One, 1989 tv film about The Manhattan Project, a rival project released the same year as Fat Man and Little Boy film

- Oppenheimer, 2023 biographical thriller film about J. Robert Oppenheimer

References

[edit]- ^ "AFI|Catalog".

- ^ Kunk, Deborah J. – "'Fat Man' Brings Bomb Alive". St. Paul Pioneer Press. October 20, 1989.

- ^ Grouett, Stephane. Manhattan Project: The Untold Story of the Making of the Atomic Bomb (Boston: Little, Brown & Company), 1967, page 324.

- ^ The Atomic Heritage Foundation. "The Mystery of Michael Merriman". Archived from the original on February 14, 2009. Retrieved June 1, 2008.

- ^ Cassidy, David C. (2005). J. Robert Oppenheimer and the American Century. New York: Pi Press. ISBN 978-0-13-147996-8.

- ^ Oppenheimer, J. Robert, Alice Kimball Smith, and Charles Weiner (1995). Robert Oppenheimer: Letters and Recollections. p. 262.

— Chafe, William Henry. The Achievement of American Liberalism. p. 141. - ^ Bird, Kai, and Martin J. Sherwin (2005). American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-375-41202-8

Conant, Jennet. 109 East Palace: Robert Oppenheimer and the Secret City of Los Alamos. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-7432-5007-8 - ^ "Films in Production". The Record. October 28, 1988.

Rohter, Larry. "Dropping a Bomb: 'Fat Man and Little Boy' explores fact and fiction at the dawn of the nuclear age". St. Petersburg Times. October 21, 1989.

Arar, Yardena. "Entertaining Thoughts 'Fat Man' had Weaknesses from Day One". Los Angeles Daily News. October 22, 1989. - ^ "Fat Man and Little Boy movie review (1989) | Roger Ebert".

- ^ "Fat Man and Little Boy (1989)". Rotten Tomatoes.

- ^ "Berlinale: 1990 Programme". berlinale.de. Retrieved 2011-03-17.

External links

[edit]- 1989 films

- 1989 drama films

- 1980s American films

- 1980s English-language films

- 1980s historical drama films

- 1980s war drama films

- American films based on actual events

- American historical drama films

- American war drama films

- American war epic films

- American World War II films

- Cultural depictions of J. Robert Oppenheimer

- Drama films based on actual events

- Epic films based on actual events

- Films about the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

- Films about the Manhattan Project

- Films about physicists

- Films directed by Roland Joffé

- Films with screenplays by Bruce Robinson

- Films scored by Ennio Morricone

- Films set in 1942

- Films set in 1945

- Films set in New Mexico

- Films shot in Mexico

- Historical epic films

- Paramount Pictures films

- 1989 in American cinema