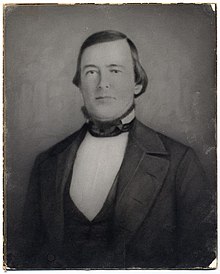

Hardin Bigelow

Hardin Bigelow | |

|---|---|

| |

| 1st Mayor of Sacramento | |

| In office April 1, 1850 – November 1850 | |

| Preceded by | Albert Maver Winn |

| Succeeded by | Horace Smith |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1809 Sacramento, California |

| Died | November 27, 1850 San Francisco, California |

| Spouse | Cynthia |

| Children | Anson Hardin Bigelow, Annette Bigelow, Almira Bigelow |

| Profession | Politician |

Hardin Bigelow (1809 in Michigan Territory – November 27, 1850 in San Francisco, California) was the first elected mayor of the city of Sacramento, California, which was known then as "Sacramento City." Bigelow's efforts to construct Sacramento's first levees won him enough support to become mayor in Sacramento's first mayoral elections in February 1850. Bigelow served seven months, from April to November, before succumbing to cholera; while he was mayor, Sacramento averted disaster in a potentially devastating flood,[1] but fell victim to a series of April fires,[1] a riot,[2] and a cholera epidemic.[3]

1850 floods

[edit]Bigelow gained popularity when he advocated and carried out the construction of Sacramento City's first levees and dams in the aftermath of the destruction caused by the 1850 Sacramento flood in January, which devastated the commercial operations on Sacramento City's Embarcadero and washed away hundreds of thousands of dollars worth of store merchandise.[4] Bigelow's efforts prevented a second inundation event in March 1850 from enacting devastation similar to that of the flood that had destroyed the city two months earlier.[1]

Mayoral office (1850)

[edit]Hardin Bigelow was the first mayor to be elected in Sacramento City, succeeding Major General Albert Maver Winn as city mayor in February 1850. Bigelow was chosen because of his foresight, which protected the city from a March 1850 flood event.[1] Under Bigelow, the Sacramento dropped the "City" portion of its name and was chartered as a city by the newly formed California State Legislature in late February.[5]

Bigelow was mayor during the 1850 Sacramento fires in April, which destroyed a number of wooden structures on the Embarcadero apiece; he was mayor during the aftermath as well, when Sacramento City rebuilt with iron-shuttered structures and with brick and stone rather than wood to reduce the likelihood of fire damage.[1]

Squatters' riot

[edit]Ever since 1848, land-seeking settlers had decided to disregard the right that John Sutter had to the land in what he called his personal empire, "New Helvetia;" settling on his land, the squatters grew at odds with the government in Sacramento. After a squatter named John T. Madden was tried and found guilty of unlawful occupation in May 1850,[6] the squatting settlers charged the government with "brute force" and worked to garner support from sympathetic settlers. Rallying around future Kansas governor Charles L. Robinson, settlers marched to free jailed prisoners James McClatchy and businessman Richard Moran from the city's prison brig in August 1850, from a ship called the La Grange.[2]

According to the local Placer Times, Bigelow had feared a full uprising and decided to strike pre-emptively against Robinson's army while they marched through downtown Sacramento. In the following fight, Bigelow was wounded to an extent where Demas Strong replaced him as acting mayor of the city. City sheriff Joseph McKinney ended the conflict on Bigelow's behalf with a tactical strike on a squatter's retreat to the east of Sacramento while Bigelow traveled southwest to San Francisco to recover.[7]

Death

[edit]Two months later in October 1850, a cholera epidemic struck the city of Sacramento, driving out eighty percent of the city populace[8] and killing seventeen of the city's physicians. Bigelow became afflicted by the disease, and died in San Francisco that month.[3] He was buried at the Sacramento Historic City Cemetery in Sacramento, California.[9][10]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Severson, p. 73

- ^ a b Severson, p. 78

- ^ a b Severson, p. 79

- ^ Severson, p. 72

- ^ Severson, p. 66

- ^ Severson, p. 76-77

- ^ Severson, p. 78-79

- ^ Flynn, p. 67

- ^ Self Guided Tour (PDF). Historic City Cemetery, Inc. January 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 9, 2017. Retrieved January 29, 2011.

- ^ Jenner, Gail L. (September 15, 2021). What Lies Beneath: California Pioneer Cemeteries and Graveyards. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 262. ISBN 978-1-4930-4896-0.

Sources

[edit]- Armstrong, Lance (January 28, 2009). "160 Years of Sacramento Leadership". Sacramento Union. Archived from the original on February 7, 2009. Retrieved July 7, 2009.

- Severson, Thor (1973). Sacramento: An Illustrated History: 1839 to 1874. California Historical Society. ISBN 0-910312-22-2.

- Flynn, Dan (1994). Inside Guide to Sacramento: The Hidden Gold of California's Capital. Sacramento, California: Embarcadero Press. ISBN 0-9643150-7-6.