Supramolecular assembly

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Molecular self-assembly |

|---|

|

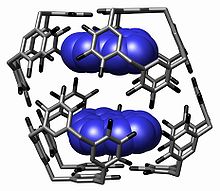

In chemistry, a supramolecular assembly is a structure consisting of molecules held together by noncovalent bonds. While a supramolecular assembly can be simply composed of two molecules (e.g., a DNA double helix or an inclusion compound), or a defined number of stoichiometrically interacting molecules within a quaternary complex, it is more often used to denote larger complexes composed of indefinite numbers of molecules that form sphere-, rod-, or sheet-like species. Colloids, liquid crystals, biomolecular condensates, micelles, liposomes and biological membranes are examples of supramolecular assemblies,[3] and their realm of study is known as supramolecular chemistry. The dimensions of supramolecular assemblies can range from nanometers to micrometers. Thus they allow access to nanoscale objects using a bottom-up approach in far fewer steps than a single molecule of similar dimensions.

The process by which a supramolecular assembly forms is called molecular self-assembly. Some try to distinguish self-assembly as the process by which individual molecules form the defined aggregate. Self-organization, then, is the process by which those aggregates create higher-order structures. This can become useful when talking about liquid crystals and block copolymers.

Templating reactions

[edit]

As studied in coordination chemistry, metal ions (usually transition metal ions) exist in solution bound to ligands, In many cases, the coordination sphere defines geometries conducive to reactions either between ligands or involving ligands and other external reagents.

A well known metal-ion-templating was described by Charles Pedersen in his synthesis of various crown ethers using metal cations as template. For example, 18-crown-6 strongly coordinates potassium ion thus can be prepared through the Williamson ether synthesis using potassium ion as the template metal.

Metal ions are frequently used for assembly of large supramolecular structures. Metal organic frameworks (MOFs) are one example.[4] MOFs are infinite structures where metal serve as nodes to connect organic ligands together. SCCs are discrete systems where selected metals and ligands undergo self-assembly to form finite supramolecular complexes,[5] usually the size and structure of the complex formed can be determined by the angularity of chosen metal-ligand bonds.

Hydrogen bond assisted supramolecular assembly

[edit]

Hydrogen bond-assisted supramolecular assembly is the process of assembling small organic molecules to form large supramolecular structures by non-covalent hydrogen bonding interactions. The directionality, reversibility, and strong bonding nature of hydrogen bond make it an attractive and useful approach in supramolecular assembly. Functional groups such as carboxylic acids, ureas, amines, and amides are commonly used to assemble higher order structures upon hydrogen bonding.

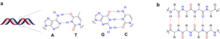

Hydrogen bond play an essential role in the assembly of secondary and tertiary structures of large biomolecules. DNA double helix is formed by hydrogen bonding between nucleobases: adenine and thymine forms two hydrogen bonds, while guanine and cytosine forms three hydrogen bonds (Figure "Hydrogen bonds in (a) DNA duplex formation"). Another prominent example of hydrogen bond-assisted assembly in nature is the formation of protein secondary structures. Both the α-helix and β-sheet are formed through hydrogen bonding between the amide hydrogen and the amide carbonyl oxygen (Figure "Hydrogen bonds in (b) protein β-sheet structure").

In supramolecular chemistry, hydrogen bonds have been broadly applied to crystal engineering, molecular recognition, and catalysis.[6][7] Hydrogen bonds are among the mostly used synthons in bottom-up approach to engineering molecular interactions in crystals. Representative hydrogen bond patterns for supramolecular assembly is shown in Figure "Representative hydrogen bond patterns in supramolecular assembly".[8] A 1: 1 mixture of cyanuric acid and melamine forms crystal with a highly dense hydrogen-bonding network. This supramolecular aggregates has been used as templates to engineering other crystal structures.[9]

Applications

[edit]Supramolecular assemblies have no specific applications but are the subject of many intriguing reactions. A supramolecular assembly of peptide amphiphiles in the form of nanofibers has been shown to promote the growth of neurons.[10] An advantage to this supramolecular approach is that the nanofibers will degrade back into the individual peptide molecules that can be broken down by the body. By self-assembling of dendritic dipeptides, hollow cylinders can be produced. The cylindrical assemblies possess internal helical order and self-organize into columnar liquid crystalline lattices. When inserted into vesicular membranes, the porous cylindrical assemblies mediate transport of protons across the membrane.[11] Self-assembly of dendrons generates arrays of nanowires.[12] Electron donor-acceptor complexes form the core of the cylindrical supramolecular assemblies, which further self-organize into two-dimensional columnar liquid crystalline lattices. Each cylindrical supramolecular assembly functions as an individual wire. High charge carrier mobilities for holes and electrons were obtained.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Dalgarno, S. J.; Tucker, S. A.; Bassil, D. B.; Atwood, J. L. (2005). "Fluorescent Guest Molecules Report Ordered Inner Phase of Host Capsules in Solution". Science. 309 (5743): 2037–9. Bibcode:2005Sci...309.2037D. doi:10.1126/science.1116579. PMID 16179474. S2CID 41468421.

- ^ Hasenknopf, Bernold; Lehn, Jean-Marie; Kneisel, Boris O.; Baum, Gerhard; Fenske, Dieter (1996). "Self-Assembly of a Circular Double Helicate". Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English. 35 (16): 1838. doi:10.1002/anie.199618381.

- ^ Ariga, Katsuhiko; Hill, Jonathan P; Lee, Michael V; Vinu, Ajayan; Charvet, Richard; Acharya, Somobrata (2008). "Challenges and breakthroughs in recent research on self-assembly". Science and Technology of Advanced Materials. 9 (1): 014109. Bibcode:2008STAdM...9a4109A. doi:10.1088/1468-6996/9/1/014109. PMC 5099804. PMID 27877935.

- ^ Cook, T. R.; Zheng, Y.; Stang, P. J. (2013). "Metal-organic frameworks and self-assembled supramolecular coordination complexes: Comparing and contrasting the design, synthesis, and functionality of metal-organic materials". Chem. Rev. 113 (1): 734–77. doi:10.1021/cr3002824. PMC 3764682. PMID 23121121.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Paul, R. L.; Bell, Z. R.; Jeffery, J. C.; McCleverty, J. A.; Ward, M. D. (2002). "Anion-templated self-assembly of tetrahedral cage complexes of cobalt(II) with bridging ligands containing two bidentate pyrazolyl-pyridine binding sites". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 99 (8): 4883–8. Bibcode:2002PNAS...99.4883P. doi:10.1073/pnas.052575199. PMC 122688. PMID 11929962.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lehn, J. M. (1985). "Supramolecular chemistry: Receptors, catalysts, and carriers". Science. 227 (4689): 849–56. Bibcode:1985Sci...227..849L. doi:10.1126/science.227.4689.849. PMID 17821215. S2CID 44733755.

- ^ Meeuwissen, J.; Reek, J. N. H. (2010). "Supramolecular catalysis beyond enzyme mimics". Nat. Chem. 2 (8): 615–21. Bibcode:2010NatCh...2..615M. doi:10.1038/nchem.744. PMID 20651721.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Desiraju, G. R. (2013). "Crystal engineering: From molecule to crystal". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135 (27): 9952–67. doi:10.1021/ja403264c. PMID 23750552.

- ^ Seto, C. T.; Whitesides, G. M. (1993). "Molecular self-assembly through hydrogen bonding: Supramolecular aggregates based on the cyanuric acid-melamine lattice". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 115 (3): 905–916. doi:10.1021/ja00056a014.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Silva, G. A.; Czeisler, C; Niece, K. L.; Beniash, E; Harrington, D. A.; Kessler, J. A.; Stupp, S. I. (2004). "Selective Differentiation of Neural Progenitor Cells by High-Epitope Density Nanofibers" (PDF). Science. 303 (5662): 1352–5. Bibcode:2004Sci...303.1352S. doi:10.1126/science.1093783. PMID 14739465. S2CID 6713941.

- ^ Percec, Virgil; Dulcey, Andrés E.; Balagurusamy, Venkatachalapathy S. K.; Miura, Yoshiko; Smidrkal, Jan; Peterca, Mihai; Nummelin, Sami; Edlund, Ulrica; Hudson, Steven D.; Heiney, Paul A.; Duan, Hu; Magonov, Sergei N.; Vinogradov, Sergei A. (2004). "Self-assembly of amphiphilic dendritic dipeptides into helical pores". Nature. 430 (7001): 764–8. Bibcode:2004Natur.430..764P. doi:10.1038/nature02770. PMID 15306805. S2CID 4405030.

- ^ Percec, V.; Glodde, M.; Bera, T. K.; Miura, Y.; Shiyanovskaya, I.; Singer, K. D.; Balagurusamy, V. S. K.; Heiney, P. A.; Schnell, I.; Rapp, A.; Spiess, H.-W.; Hudson, S. D.; Duan, H. (2002). "Self-organization of supramolecular helical dendrimers into complex electronic materials". Nature. 417 (6905): 384–7. Bibcode:2002Natur.417..384P. doi:10.1038/nature01072. PMID 12352988. S2CID 1708646.