Military history of Thailand

| History of Thailand |

|---|

|

|

|

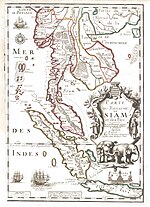

The military history of Thailand encompasses a thousand years of armed struggle, from wars of independence from the powerful Khmer Empire, through to struggles with her regional rivals of Burma and Vietnam and periods of tense standoff and conflict with the colonial empires of Britain and France. Thailand's military history, dominated by her centrality in the south-eastern Asian region, the significance of her far flung and often hostile terrain, and the changing nature of military technology, has had a decisive impact on the evolution of both Thailand and her neighbours as modern nation states. In the post-war era, Thailand's military relationship with the United States has seen her play an important role in both the Cold War and the recent War on Terror, whilst her military's involvement in domestic politics has brought frequent international attention.

Sukhothai Period (1238–1350)

[edit]The Siamese military state emerged from the disintegration in the 14th century of the once powerful Khmer Empire. Once a powerful military state centred on what is today termed Cambodia, the Khmer dominated the region through the use of irregular military led by captains owing personal loyalty to the Khmer warrior kings, and leading conscripted peasants levied during the dry seasons. Primarily based around its infantry, the Khmer army was typically reinforced by war elephants and later adopted ballista artillery from China.

By the end of the period, indigenous revolts amongst Khmer territories in Siam and Vietnam, and external attack from the independent kingdom of Champa, sapped Khmer strength. After the sack of the Khmer capital Angkor Wat by Champa forces in 1178–79, Khmer's ability to control its wider territories diminished rapidly. The first Siamese kingdom to gain independence, Sukhothai, soon joined to the newly independent Ayutthaya kingdom in 1350.

Ayutthaya Period (1350–1767)

[edit]After 1352 Ayutthaya became the main rival to the failing Khmer empire, leading to Ayutthayan Sack of Angkor in 1431. The subsequent years saw constant warfare as numerous states attempted to exploit the collapse of Khmer hegemony. As none of the parties in the region possessed a technological advantage, the outcome of battles was usually determined by the size of the armies.

Ayutthaya–Lan Na War (1441–1474)

[edit]In 1441, a war started between the Kingdom of Ayutthaya and the Kingdom of Lan Na. Neither side were able to overcome the other and they were left in a stalemate.

Burmese–Siamese War (1547–1549)

[edit]In 1547, King Tabinshwehti invaded Siam and almost captured Ayutthaya, but had to retreat. It was a Siamese pyrrhic victory as they lost the Tenasserim Coast to Burma in exchange for peace.

Burmese–Siamese War (1563–1564)

[edit]In 1563, King Bayinnaung invaded Siam and managed to conquer it as vassals. The Siamese tried to revolt against Burmese rule in 1568, but the Burmese were successful in putting down the rebellion.

The use of war elephants continued, with some battles seeing personal combat between commanders on elephants.[1] In 1592, Nanda Bayin king of Toungoo ordered his son Mingyi Swa to attack Ayutthaya Naresuan encamped his armies at Yuddhahatthi. The Burmese then arrived, leading to the Battle of Yuddhahatthi. Naresuan was able to killed Mingyi Swa while both were on elephants during the battle. After that Burmese army withdrew from Ayutthaya in 1599, Naresuan occupied the city of Pegu but Minye Thihathu Viceroy of Toungoo took Nanda Bayin and left for Toungoo. When Naresuan reached Pegu, what he found was only the city in ruins. He requested Toungoo to send Nanda Bayin back to him but Minye Thihathu refused. After each victorious campaign, Ayutthaya carried away a number of conquered people to its own territory, where they were assimilated and added to the labour force. To the south, Ayutthaya easily achieved domination over the outlying Malay states. To the north, however, the kingdom of Burma posed a potential military threat to the Siamese kingdom. Although frequently split and divided in the 16th century, during periods of unity Burma could, and did, defeat Ayutthaya in battle, such as in 1564 and 1569. What followed was another prolonged period of Burmese disunity.

Burma successfully invaded Ayutthaya again in 1767, this time burning the capital and temporarily dividing the country. General, later King, Taksin assumed power and defeated the Burmese at the battle of Pho Sam Ton Camp later in 1767.[2][3] With Chinese political support, Taksin fought several campaigns against Vietnam, wresting Cambodia from Vietnamese control in 1779.[4] In the north, Taksin's forces freed the Kingdom of Lanna from Burmese control, creating an important buffer zone, and conquered the Laotian kingdoms in 1778. Ultimately, internal political dissent, in part fed by concerns over Chinese influence, brought the deposition of Taksin and the establishment of General Chakri as Rama I in 1782 and the founding of the Rattanakosin Kingdom with its new capital city at Bangkok.

Military competition for regional hegemony continued, with continued Siamese military operations to maintain their control over the kingdom of Cambodia, and Siamese support for the removal of the hostile Tây Sơn dynasty in Vietnam with the initially compliant ruler of Nguyễn Ánh.[5] In later years, the Vietnamese emperor was less cooperative, supporting a Cambodian rebellion against Siamese authority and placing a Vietnamese garrison in Phnom Penh, the Cambodian capital, for several years.[6] Conflict with Burma was renewed in the two campaigns of the Burmo-Siamese war (1785–86), seeing initial Burmese successes in both years turned around by decisive Siamese victories. The accession of Rama II in 1809 saw a final Burmese invasion, the Thalang campaign, attempting to take advantage of the succession of power. Despite the destruction of Thalang, Rama's ultimate victory affirmed Siamese relative military superiority against Burma, and this conflict was to represent the final invasion of Siamese territory by Burma.

Siam and the European military threat (1826–1932)

[edit]The British victories over Burma in 1826 set the stage for a century in which the military history of Thailand was to be dominated by the threat of European colonialism. Initially, however, Siamese concern remained focused on its traditional rivals of Burma and Vietnam. Siam intervened in support of Britain against Burma in 1826, but her lackluster performance inspired Chao Anouvong's surprise attack on Korat. Lady Mo's resistance established her as a cultural heroine, and General Bodindecha's victory two years later established him as a major figure in Thai military history. His successful campaign in the Siamese–Vietnamese War (1841–1845) reaffirmed Siamese power over Cambodia. In 1849, weakening Burmese power encouraged revolt amongst the Burmese controlled Shan states of Kengtung and Chiang Hung. Chiang Hung repeatedly sought Siamese support, and ultimately Siam responded with the initial dispatch of forces in 1852. Both armies found difficulties campaigning in the northern mountainous highlands, and it took until 1855 before the Siamese finally reached Kengtung, though with great difficulty and the exhaustion of Siamese resources ultimately resulted in their retreat.[7] These wars continued to be fought in the traditional mode, with war elephants deployed in the field carrying light artillery during the period,[8] often being a decisive factor in battle.[9] Meanwhile, the visible military weaknesses of China in the First and Second Opium Wars with Britain and later France between the 1830s and 1860s encouraged Siam to reject Chinese suzerainty in the 1850s. Siam, however, was under military and trade pressure itself from the European powers, and as King Rama III reportedly said on his deathbed in 1851: "We will have no more wars with Burma and Vietnam. We will have them only with the West."[citation needed]

Under Napoleon III, France escalated the military pressure on Siam from the east. France's naval interventions in Vietnam in the 1840s gave way to a concerted imperial campaign. Saigon fell in 1859, with French ascendancy in Vietnam being confirmed in 1874. France took Cambodia in 1863, combining it with Vietnam to form the colony of Indochina in 1887. From the south, Britain's involvement in the Larut and Klang wars of the 1870s increased both its grip over and political investment in the Malay states. From the north, Britain, triumphant in the Second Anglo-Burmese War of 1852, ultimately concluded its conquest of Burma in the Third Anglo-Burmese War and had incorporated the Kingdom of Burma into the British Raj by 1886. European military dominance was driven largely by the dominance of European naval power, coal powered vessels, increasingly iron clad, eclipsing the local brown water navies. Nonetheless, European campaigns remained limited by the difficulties and costs of logistics and the climate, especially the threat of malaria.

Siam's response under King Mongkut was to commence a wide programme of reform on the Western model, which including the Siam military. The Royal Thai Army traces its origins as a standing force to Mongkut's creation of the Royal Siamese Army as a standing force in the European tradition in 1852. By 1887, Siam had permanent military commands, again in the European fashion, and by the end of the century, Siam had also acquired a Royal Navy from 1875 with a Danish naval reserve officer, Andreas du Plessis de Richelieu in charge, and after his departure in 1902 with the Thai noble title Phraya Chonlayutthayothin (Thai: พระยาชลยุทธโยธินทร์) under the reforms of Admiral Prince Abhakara Kiartiwongse. Siam's increasing focus on centralised military force to deter European invasion came at the cost of the former decentralised military and political arrangements, beginning a trend towards centralised military power that would continue into 20th century Thailand. Despite the growing Siamese military strength, Siam's independence during much of the late-19th century hinged on the ongoing rivalry between Britain and France across the region, especially in the search for lucrative trade routes into the Chinese hinterlands. By developing an increasing sophisticated military force and playing one colonial rival against the other, successive Siamese monarchs were able to maintain an uneasy truce until the 1890s.

The closing act of this struggle was the French occupation of eastern Thai territory in the Franco-Siamese conflict of 1893, which paved the way for an uneasy peace between Siam and France in the region for the next forty years. French Indochina's Governor-General had sent an envoy to Bangkok to bring Laos under French rule, backed by the threat of French military force. The Siamese government, mistakenly believing that they would be supported by the British, refused to concede their territories east of the Mekong River and instead reinforced their military and administrative presence there.[10] Spurred on by the expulsion of French merchants on suspicion of opium smuggling,[10][dead link][11] and the suicide of a French diplomat returning from Siam, the French took the Siamese refusal to concede its eastern territories as a causus belli.[11][12]

In 1893 the French ordered their navy to sail up the Chao Phraya River to Bangkok. With their guns trained on the Siamese royal palace, the French delivered an ultimatum to the Siamese to hand over the disputed territories and to pay indemnities for the fighting so far. When Siam did not immediately comply unconditionally to the ultimatum, the French blockaded the Siamese coast. Unable to respond by sea or on land, the Siamese submitted fully to the French terms, finding no support from the British.[12] The conflict led to the signature of the Franco-Siamese Treaty in which the Siamese conceded Laos to France, an act that led to a significant expansion of French Indochina.

In 1904 the French and the British put aside their differences with the Entente Cordiale, which ended their dispute over routes in southern Asia and also removed the Siamese option for using one colonial power as military protection against another. Meanwhile, the Anglo-Siamese Treaty of 1909 produced a compromise, largely in Britain's favour, between Britain and Siam over the disputed territories in the north of Malaya.[13] Siam's next conflict was its two-year involvement in the First World War, fighting on the side of the Entente Powers, the only independent Asian nation with land forces in Europe during the Great War.[14] The result of this intervention in 1917 was the revision or complete cancellation of some of the unequal trade treaties with the United States, France, and the British Empire – but not the return of the bulk of the disputed Siamese territories lost in the previous century.[15]

Second World War and Alliance with Japan (1932–1945)

[edit]For Thailand – renamed from Siam in 1939 – the Second World War involved both the bilateral struggle between the Axis and Allied forces in the region and the regional struggle across Southeast Asia between historic rivals. Like other regional actors, Thailand – under military rule following the coup of 1932 and led by Prime Minister Major-General Plaek Pibulsonggram (popularly known as "Phibun") – was to exploit the changes in power caused by the fall of France and the expansion of Japan to attempt to offset the losses of the previous century. Thailand's considerable investment in her army, based on a mixture of British and German equipment, and her air force – a blend of Japanese and American aircraft – was about to be put to use.

The conflict fell into three broad phases. During the initial phase following the fall of France in 1940 and the establishment of Japanese bases in France's Far Eastern colonial territories, Thailand opened up an air offensive along the Mekong frontier, attacking Vientiane, Sisophon, and Battambang with relative impunity. In early January 1941, the Thai Army launched a land offensive, swiftly taking Laos whilst entering into a more challenging battle for Cambodia where the pursuit of French units there proved more difficult. At sea, however, the heavier forces of the French navy quickly achieved dominance, winning skirmishes at Ko Chang, followed by the French victory at the Battle of Ko Chang. The Japanese mediated the conflict, and a general armistice was agreed 28 January, followed by a peace treaty signed in Tokyo on 9 May,[16][17] with the French being coerced by the Japanese into relinquishing their hold on the disputed territories.

During the second phase, Japan took advantage of the weakening British hold on the region to invade Siam, seeing the country as an obstacle on the route south to British-held Malaya and its vital oil supplies, and northwest to Burma. On 8 December 1941, after several hours of minimal fighting between Siamese and Japanese troops, Thailand acceded to Japanese demands for access. Later that month Phibun signed a mutual offensive-defensive alliance pact with Japan[18] giving the Japanese full access to Thai railways, roads, airfields, naval bases, warehouses, communications systems, and barracks. With Japanese support, Thailand annexed those former possessions in northern Malaya it had been unable to acquire under the 1909 treaty, and conducted a campaign against its former allies in the Shan states of Burma along its northern frontier.[19][18][20]

By the final stages of the war, however, the weakening position of Japan across the region and the Japanese requisition of supplies and materiel reduced the military benefits to Siam, turning an unequal alliance into an increasingly obvious occupation. Allied air power achieved superiority over the country, bombing Bangkok and other targets. The sympathies of the civilian political elite, moved perceptibly against the Phibun regime and the military, forcing the prime minister from office in June 1944. With the fall of Japan, France and Britain insisted on the return of those lands annexed by Siam during the conflict, returning the situation to the situation ante bellum.

The conflict highlighted the new importance of air power across the region, for example the use of dive bombers against French troops in 1941[16] or the use of air reconnaissance in the northern mountains.[21] It had also highlighted the importance of well-trained pilots to effective air war.[22] Ultimately, the conflict emphasised the challenges of logistics across often impassable terrain, which generated expensive military campaigns – a feature to reemerge in the postwar period during the conflicts in French Indochina.

Thailand and regional Communism (1945–90)

[edit]

Thailand's military history in the post-war period was dominated by the growth of Communism across the region, which rapidly became one of the fault lines in the Cold War. Thailand's successive governments found that the Communist bloc in south-east Asia largely consisted of their historical military rivals, and were increasing drawn both into the regional struggle and into having to deal with Communist insurgency at home. Thailand's postwar leaders were mainly traditionalists, seeking to restore the prestige of the monarchy and to defeat the growth of Communism, which was closely associated with Thailand's traditional enemies, the Vietnamese – now in open revolt against the French. Following Thailand's participation in the Korean War,[23] and with the steady growth of US involvement in the region, Thailand formally became a US ally in 1954 with the formation of the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO).[24]

Whilst the war in Indochina was being fought between the Vietnamese and the French, Thailand – disliking both her old rivals equally – initially refrained from entering the conflict, but once it became a war between the US and the Vietnamese Communists, Thailand committed itself strongly to the US side. Thailand concluded a secret military agreement with the US in 1961, and in 1963 openly allowed the use of their territories as air bases and troop bases for US forces before finally sending her own troops to Vietnam.[25] A Royal Thai Volunteer Regiment (the "Queen's Cobras") and later the Royal Thai Army Expeditionary Division ("Black Panthers"), then a brigade, served in South Vietnam from September 1967 to March 1972.[26] Thailand was however more involved with the secret war and covert operations in Laos from 1964 to 1972. The Vietnamese retaliated by supporting the Communist Party of Thailand's insurgency in various parts of the country. By 1975 relations between Bangkok and Washington had soured; eventually all US military personnel and bases were forced to withdraw and direct Thai involvement in the conflict came to an end.

The Communist victory in Vietnam further emboldened the Communist movement within Thailand. In 1976, Thai military personnel, police and others, were seen shooting at protesters at Thammasat University. Many were killed and many survivors were abused.[27] This came to be known as the Thammasat University massacre. After this massacre and the repressive policies of Tanin Kraivixien sympathies for the movement increased, and by the late 1970s it was estimated that the movement had about 12,000 armed insurgents,[28] mostly based in the northeast along the Laotian-Khmer border. Counter-insurgency campaigns by the Thai military meant that by the 1980s insurgent activities had been largely defeated. Meanwhile, the Vietnamese invasion of Cambodia in 1978 to remove the Pol Pot regime – tacitly supported by Thailand and China – brought the Vietnamese-Thailand conflict up to the Thai border, resulting in small border raids and incursions by Vietnamese against the remaining Khmer Rouge camps inside Thai territory, that lasted until 1988. Thailand, meanwhile, with US support sponsored the creation of the Khmer People's National Liberation Front, which operated against the new Vietnamese-backed Cambodian government from 1979 onwards from bases inside Thailand. Similar small skirmishes emerged along the Thai-Laotian border in 1987–1988.

Post-communist period

[edit]The last twenty years of Thailand's military history has been dominated less by the threat of external attack, but by the role of the Thai military in internal politics. For most of the 1980s, Thailand was ruled by prime minister Prem Tinsulanonda, a democratically inclined leader who restored parliamentary politics. Thereafter the country remained a democracy apart from a brief period of military rule from 1991 to 1992, until, in 2006 mass protests against the Thai Rak Thai party's alleged corruption prompted the military to stage a coup d'état. A general election in December 2007 restored a civilian government, but the issue of the Thai military's frequent involvement in domestic politics remains.

Meanwhile, the long-running southern insurgency, waged by the ethnic Malays and Islamic rebels in the three southern provinces of Yala, Pattani, and Narathiwat intensified in 2004, with attacks on ethnic Thai civilians by insurgents escalating.[29][failed verification] The Royal Thai Armed Forces in turn responded with force.[30] Casualties currently stands at 155 Thai military personnel killed against 1,600 insurgents killed and about 1,500 captured, against the backdrop of about 2,729 civilian casualties.[31] Strong US military support for Thailand under President Bush, as part of the US War on Terror, assisted the Thai military in this counter-insurgency role,[32] although discussions continue in the Royal Thai Government as to the role of the military, vis-à-vis civilians, in the leadership of this campaign.[33] US Air force units have also been permitted to use Thai air bases once more, flying missions over Afghanistan and Iraq in 2001 and 2003 respectively.

The Thai military maintains strong regional relations under the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) organisation, illustrated by the annual Cobra Gold exercises, the latest in 2018, involving soldiers from Thailand, the US, Japan, Singapore, and Indonesia. The exercises are the largest military exercises in Southeast Asia.[34][35] This association, bringing together many former enemies, plays an important part in ensuring ongoing peace and stability across the region.

References

[edit]- ^ For example the fight between Burmese crown prince Mingyi Swa and by Siamese King Naresuan in the battle of Battle of Yuthahatthi on what is now reckoned as 18 January 1593, and observed as Armed Forces Day.

- ^ Arjarn Tony Moore/Khun Clint Heyliger Siamese & Thai Hero's & Heroines Archived 12 January 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Royal Thai Army Radio and Television King Taksin's Liberating Archived 16 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Norman G. Owen (2005). The Emergence Of Modern Southeast Asia. National University of Singapore Press. p. 94. ISBN 9971-69-328-3.

- ^ Nicholas Tarling (1999). The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia. Cambridge University Press. p. 584. ISBN 0-521-35505-2.

- ^ Buttinger, Joseph (1958). The Smaller Dragon: A Political History of Vietnam. Praeger, p. 305.

- ^ Search-thais.com Archived 28 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ De la Bissachere, cited Nossov, K. War Elephants, 2003, p. 40.

- ^ Heath, I. Armies of the Nineteenth Century: Asia, Burma and Indo-China, 2003, p. 182.

- ^ a b Stuart-Fox 1997[dead link]

- ^ a b Simms, Peter; Simms, Sanda (2001). The Kingdoms of Laos. Psychology Press. ISBN 9780700715312. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- ^ a b Ooi 2004[dead link]

- ^ U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Intelligence and Research, Office of the Geographer, "International Boundary Study: Malaysia - Thailand Boundary" No. 57 Archived 16 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine, 15 November 1965.

- ^ "90th Anniversary of World War I. This Is The History of Siamese Volunteer Corps". Thai Military Information Blog. 10 November 2008. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- ^ "Thailand and the First World War". First World War. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- ^ a b Young, Edward M. (1995) Aerial Nationalism: A History of Aviation in Thailand. Smithsonian Institution Press.

- ^ Hesse d'Alzon, Claude. (1985) La Présence militaire française en Indochine. Château de Vincennes: Publications du service historique de l'Armée de Terre.

- ^ a b E. Bruce Reynolds. (1994) Thailand and Japan's Southern Advance 1940–1945. St. Martin's Press.

- ^ "Thailand and the Second World War 1941- 45". Archived from the original on 27 October 2009. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- ^ Judith A. Stowe. (1991) Siam becomes Thailand: A Story of Intrigue. Hurst & Company.

- ^ "The Drive on Kengtung". Archived from the original on 31 March 2009. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- ^ Elphick, Peter. (1995) Singapore, the Pregnable Fortress: A Study in Deception, Discord and Desertion. Coronet Books.

- ^ The United States Army Homepage Archived 16 July 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Milestones: 1953–1960 - Office of the Historian". history.state.gov. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ^ Ruth, Richard A (7 November 2017). "Why Thailand Takes Pride in the Vietnam War". New York Times. Retrieved 24 August 2018.

- ^ Stanton, 'Vietnam Order of Battle,' 270–271.

- ^ "6ตุลา".

- ^ "Thailand Communist Insurgency 1959-Present". Archived from the original on 5 July 2008. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- ^ The New York Times

- ^ "Global Security". Retrieved 3 December 2014.[not specific enough to verify]

- ^ "Unk". Archived from the original on 17 June 2008. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- ^ Crispin, Shawn W. "What Obama means to Bangkok". Asia Times. Archived from the original on 17 December 2008. Retrieved 24 August 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Head, Jonathan. "Thailand's savage southern conflict". BBC. Retrieved 24 August 2018.

- ^ Parameswaran, Prashanth (31 January 2018). "What Will the 2018 Cobra Gold Military Exercises in Thailand Look Like?". The Diplomat. Retrieved 24 August 2018.

- ^ "Cobra Gold 2009 Gallery". Thai Military Information Blog. 7 March 2009. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

Further reading

[edit]- Ruth, Richard A (September 2010). In Buddha's Company; Thai Soldiers in the Vietnam War (Paper ed.). University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 9780824834890. Retrieved 24 August 2018.