Virtual pet

This article needs to be updated. (January 2021) |

|

| Part of a series on |

| Simulation video games |

|---|

A virtual pet (also known as a digital pet, artificial pet,[1] or pet-raising simulation) is a type of artificial human companion. They are usually kept for companionship or enjoyment, or as an alternative to a real pet.

Digital pets have no concrete physical form other than the hardware they run on. Interaction with virtual pets may or may not be goal oriented. If it is, then the user must keep it alive as long as possible and often help it to grow into higher forms. Keeping the pet alive and growing often requires feeding, grooming and playing with the pet. Some digital pets require more than just food to keep them alive. Daily interaction is required in the form of playing games, virtual petting, providing love and acknowledgment can help keep your virtual pet happy and growing healthy.[2]

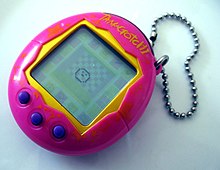

Digital pets can be simulations of real animals, as in the Petz series, or fantasy ones, like the Tamagotchi or Digimon series. Unlike biological simulations, the pet does not usually reproduce.[1]

Types

[edit]Web-based

[edit]Virtual pet sites are usually free to play for all who sign up. They can be accessed through web browsers and often include a virtual community, such as Neopia in Neopets. In these worlds, a user can play games to earn virtual money which is usually spent on items and food for pets. One large branch of virtual pet games are sim horse games.[3]

Some sites adopt out pets to put on a webpage and use for role-playing in chat rooms. They often require the adoptee to have a page ready for their pet. Sometimes they have a setup for breeding one's pets and then adopting them out.

Software-based

[edit]There are many video games that focus on the care, raising, breeding or exhibition of simulated animals. Such games are described as a sub-class of life simulation game. Since the computing power is more powerful than with webpage or gadget based digital pets, these are usually able to achieve a higher level of visual effects and interactivity. Pet-raising simulations often lack a victory condition or challenge, and can be classified as software toys.[1]

The pet may be capable of learning to do a variety of tasks. "This quality of rich intelligence distinguishes artificial pets from other kinds of A-life, in which individuals have simple rules but the population as a whole develops emergent properties".[1] For artificial pets, their behaviors are typically "preprogrammed and are not truly emergent".[1]

A screen mate is a downloadable virtual pet that creates a small animation that walks around a computer desktop and over open screens unpredictably. Each pets is a small animation of an animal (such as a sheep or a frog, or in some cases a human or bottle cap) that can be interacted by clicking on or dragging, which lifts the pet as if you were picking it up. Most screen mates are free to download and used for entertainment purposes.[4]

History

[edit]The first-known virtual pet was a screen-cursor chasing cat called Neko. It was rather called a "desktop pet" since at that time the term "virtual pet" did not exist.

PF.Magic released the first widely popular virtual pets in 1995 with Dogz,[5] followed by Catz in the spring of 1996, eventually becoming a franchise known as Petz. The digital pets were further popularized when Tamagotchi[6] and Digimon were introduced in 1996 and 1997.[7]

Digital pets like Tamagotchi and Digimon were a massive fad across Japan, the United States and United Kingdom during the late 1990s. Today, there are also "Digital Pets" which have physical robotic bodies, known as Ludobots or Entertainment robots.

From the late 1990s to the early 2000s, virtual pets specialized to be official mascots of personal websites known as "cyber pets" (or "cyberpets") could be especially seen in websites hosted with GeoCities, Tripod, or Angelfire. There were also webpages which allowed users to "adopt" cyber pets for their websites.

Controversy

[edit]The popularity of virtual pets in the United States, and the constant need for attention the pets required, led to them being banned from schools across the country,[8] a move that hastened the virtual pet's decline from popularity.[citation needed]

A Mad cover on regular issue #362, October 1997 shows a gun being pointed at a virtual pet with Alfred E. Neuman's face and the line "If you don't buy this magazine, we'll kill this virtual pet!" Illustrated by Mark Fredrickson. The cover parodies the January 1973 issue of National Lampoon which depicted a gun being held to a real dog's head and the line, "If you don't buy this magazine, we'll kill this dog."[9]

Relationship with digital pet

[edit]There is research concerning the relationship between digital pets and their owners, and their impact on the emotions of people. For example, Furby affects the way people think about their identity, and many children think that Furby is alive in a "Furby kind of way" in Sherry Turkle's research.[10]

Common features

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2021) |

There are many common features between different digital pets, some of them are used to give a sense of reality to the user (such as the pet responding to "touch"), and some for enhancing playability (such as training).

Communication

[edit]With advanced video gaming technology, most modern digital pets do not show a message box nor icon to display the pet's internal variable, health state or emotion like earlier generations (such as Tamagotchi). Instead, users can only understand the pet by interpreting their actions, body language, facial expressions, etc. This helps to make a pet's behavior seem natural, rather than calculated, and fosters a feeling of a relationship between user and digital pet.

Sense of reality

[edit]To give a sense of reality to users, most digital pets have certain level of autonomy and unpredictability. The user can interact with the pet and this process of personalizing can make the pet more distinctive. Personalizing increases the feeling of responsibility for the pet to the user.[11][12] For example, if a Tamagotchi is unattended for long enough, it will "die".

Interactivity

[edit]To increase user's personal attachment to the pet, the pet interacts with the user. Interactivity can be classified into two categories: Short-term and long-term.

Short-term interactivity includes direct interaction or action to reaction from the pet. Example: "touch" a pet with mouse cursor and the pet will give a direct response to the "touching".

Long-term interactivity includes action that affects the pet's growth, behavior or life span. For example, training a pet may have a good effect on the pet's behavior. Long-term interactivity is quite important for a sense of reality as the user would think that he has some lasting influence on the pet.

Two kinds of interactivity are often combined. Training (long-term interaction) may happen through continuing short-term interaction. Similarly, playing with a pet (short-term interaction) may, if continued over the long term, make the pet more optimistic.

Example of common features

[edit]- Responds to calling

- Responds to touching

- Training the pet

- Supplies or toys for the pet

- Dressing up the pet

- Competition or trial amongst pets

- Meeting other pets

- Complaining when it needs care

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Rollings, Andrew; Ernest Adams (2003). Andrew Rollings and Ernest Adams on Game Design. New Riders Publishing. pp. 477–487. ISBN 978-1-59273-001-8. Archived from the original on 2 May 2020. Retrieved 6 December 2011.

- ^ "From Tamagotchi to "Nintendogs": Why people like digital pets". Corinspired. 14 June 2021. Archived from the original on 10 November 2021. Retrieved 10 November 2021.

- ^ "Are virtual pets video games?". boardgamestips.com. Archived from the original on 9 January 2022. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

- ^ J. D. Biersdorfer (24 February 2000). "Screen Mates for Fun or Profit". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 4 June 2022. Retrieved 18 February 2017.

- ^ Rita Koselka (2 December 1996). "Save on dog food". Forbes: 237–238.

- ^ "Tamagotchi reborn as an adult". 4 February 2004. Archived from the original on 21 March 2022. Retrieved 1 March 2021.

- ^ "Remember Tamagotchi? The 1990s' cult toys are back". The Straits Times. 12 April 2017. Archived from the original on 12 April 2017. Retrieved 1 March 2021.

- ^ "Tamagotchi: Love It, Feed It, Mourn It". archive.nytimes.com. Archived from the original on 28 November 2022. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

- ^ MAD Cover Site Archived 16 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine, MAD #362 October 1997.

- ^ Katie Hafner, What Do You Mean, `It's Just Like a Real Dog'? Archived 5 February 2023 at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times, May 25, 2000

- ^ Frédéric Kaplan Free creatures : The role of uselessness in the design of artificial pets, 2000 Archived 16 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Frank, A.; Stern, A.; and Resner, B. 1997. Socially intelligent virtual petz. In Socially Intelligent Agents.