Jack jumper ant

| Jack jumper ant | |

|---|---|

| |

| Worker ant | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Formicidae |

| Subfamily: | Myrmeciinae |

| Genus: | Myrmecia |

| Species: | M. pilosula

|

| Binomial name | |

| Myrmecia pilosula F. Smith, 1858

| |

| |

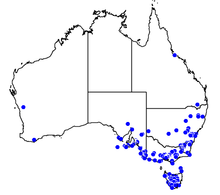

| Occurrences of the jack jumper ant reported to the Atlas of Living Australia as of May 2015 | |

| Synonyms[1][2] | |

| |

The jack jumper ant (Myrmecia pilosula), also known as the jack jumper, jumping jack, hopper ant, or jumper ant, is a species of venomous ant native to Australia. Most frequently found in Tasmania and southeast mainland Australia, it is a member of the genus Myrmecia, subfamily Myrmeciinae, and was formally described and named by British entomologist Frederick Smith in 1858. This species is known for its ability to jump long distances. These ants are large; workers and males are about the same size: 12 to 14 mm (0.47 to 0.55 in) for workers, and 11 to 12 mm (0.43 to 0.47 in) for males. The queen measures roughly 14 to 16 mm (0.55 to 0.63 in) long and is similar in appearance to workers, whereas males are identifiable by their perceptibly smaller mandibles.

Jack jumper ants are primarily active during the day and live in open habitats, nesting in bushland, woodlands, and dry open forests, surrounded by gravel and sandy soil, which can be found in rural areas and are less common in urban areas. They prey on small insects and use their barbless stingers to kill other insects by injecting venom. Other ants and predatory invertebrates prey on the jack jumper ant. The average worker has a life expectancy of over one year. Workers are gamergates, allowing them to reproduce with drones, whether or not a queen is present in the colony. The ant is a part of the Myrmecia pilosula species complex; this ant and other members of the complex are known to have a single pair of chromosomes.

Their sting generally only causes a mild local reaction in humans; however, it is one of the few ant species that can be dangerous to humans, along with other ants in the genus Myrmecia. The ant venom is particularly immunogenic for an insect venom; the venom causes about 90% of Australian ant allergies. In endemic areas, up to 3% of the human population has developed an allergy to the venom and about half of these allergic people can suffer from anaphylactic reactions (increased heart rate, falling blood pressure, and other symptoms), which can lead to death on rare occasions. Between 1980 and 2000, four deaths were due to anaphylaxis from jack jumper stings, all of them in Tasmania. Individuals prone to severe allergic reactions caused by the ant's sting can be treated with allergen immunotherapy (desensitisation).

Taxonomy and common names

[edit]

The specific name derives from the Latin word pilosa, meaning 'covered with soft hair'.[4][5] The ant was first identified in 1858 by British entomologist Frederick Smith in his Catalogue of hymenopterous insects in the collection of the British Museum part VI, under the binomial name Myrmecia pilosula from specimens he collected in Hobart in Tasmania.[6][7] There, Smith described the specimens of a worker, queen, and male.[6] The type specimen is located in the British Museum in London.[8] In 1922, American entomologist William Morton Wheeler established the subgenus Halmamyrmecia characterised by its jumping behaviour, of which the jack jumper ant was designated as the type species.[9] However, John Clark later synonymised Halmamyrmecia under the subgenus Promyrmecia in 1927[10] and placed the ant in the subgenus in 1943.[8][11] William Brown synonymised Promyrmecia due to the lack of morphological evidence that would make it distinct from Myrmecia and later placed the jack jumper ant in the genus in 1953.[1][12]

One synonym for the species has been published – Ponera ruginoda (also titled Myrmecia ruginoda),[13] described by Smith in the same work, and a male holotype specimen was originally described for this synonym.[7][14] P. ruginoda was initially placed into the genera Ectatomma and Rhytidoponera,[15][16] but it was later classified as a junior synonym of the jack jumper ant, after specimens of each were compared.[1][17] The M. pilosula species complex was first defined by Italian entomologist Carlo Emery.[16] The species complex is a monophyletic group, where the species are closely related to each other, but their actual genetic relationship is distant.[18][19][20][21] Members of this group include M. apicalis, M. chasei, M. chrysogaster, M. croslandi, M. cydista, M. dispar, M. elegans, M. harderi, M. ludlowi, M. michaelseni, M. occidentalis M. queenslandica, M. rugosa, and M. varians.[22] Additional species that were described in this group in 2015 include M. banksi, M. haskinsorum, M. imaii, and M. impaternata.[23]

Their characteristic jumping motion when agitated or foraging inspires the common name "jack jumper", a behaviour also shared with other Myrmecia ants, such as M. nigrocincta.[24] This is the most common name for the ant, along with "black jumper,"[8] "hopper ant",[25] "jumper ant",[26] "jumping ant",[27] "jumping jack"[26] and "skipper ant".[28] It is also named after the jumping-jack firecracker.[29] The species is a member of the genus Myrmecia, a part of the subfamily Myrmeciinae.[30][31][32]

Description

[edit]

Like its relatives, the ant possesses a powerful sting and large mandibles. These ants can be black or blackish-red in colour, and may have yellow or orange legs. The ant is medium-sized in comparison to other Myrmecia species, where workers are typically 12 to 14 mm (0.47 to 0.55 in) long.[8] Excluding mandibles, jack jumpers measure 10 millimetres (0.39 in) in length.[33] The ant's antennae, tibiae, tarsi, and mandibles are also yellow or orange.[8] Pubescence (hair) on the ant is greyish, short and erect, and is longer and more abundant on their gaster, absent on their antennae, and short and suberect on their legs.[8] The pubescence on the male is grey and long, and abundant throughout the ant's body, but it shortens on the legs.[8] The mandibles are long and slender (measuring 4.2 mm (0.17 in)), and concave around the outer border.[33]

The queen has a similar appearance to the workers, but her middle body is more irregular and coarser.[8] The queen is also the largest, measuring 14 to 16 mm (0.55 to 0.63 in) in length.[8] Males are either smaller or around the same size as workers, measuring 11 to 12 mm (0.43 to 0.47 in).[8] Males also have much smaller, triangular mandibles than workers and queens. The mandibles on the male contain a large tooth at the centre, among the apex and the base of the inner border.[8] Punctures (tiny dots) are noticeable on the head, which are large and shallow, and the thorax and node are also irregularly punctuated.[8] The pubescence on the male's gaster is white and yellowish.[8]

Distribution and habitat

[edit]

Jack jumper ants are abundant in most of Australia, being among the most common bull ant to be encountered.[34] The ants can be found in the south-western tip of Western Australia,[35] where it has been seen in the sand hills around Albany, Mundaring, Denmark and Esperance.[1] The ant is rarely sighted in the northern regions of Western Australia.[8] In South Australia, it is commonly found in the south-east regions of the state, frequently encountered in Mount Lofty (particularly the Adelaide Hills), Normanville, Hallett Cove and Aldgate, but it is not found in north-western regions.[35] There are dense populations on the western seaboard of Kangaroo Island.[1] Jack jumpers are widespread throughout the whole of Victoria, but the species is uncommon in Melbourne.[27] However, populations have been collected from the suburb of Elsternwick,[36] and they are commonly found in the Great Otway Ranges, with many nests observed around Gellibrand.[37] In New South Wales, nests are found throughout the entire state (with the exception of north-western New South Wales), but dense populations are mostly found in the Snowy Mountains, Blue Mountains and coastal regions.[38] The ants are widespread in the Australian Capital Territory. In Queensland, the ants are only found along the south-eastern coastlines of the state, where populations are frequently encountered in the Bunya Mountains, Fletcher, Stanthorpe, Sunshine Coast, Tamborine Mountain and Millmerran, and have been found as far north as Atherton Tablelands.[a][8] The ant also resides in all of Tasmania, and their presence in the Northern Territory has not been verified.[39]

Jack jumper ants live in open habitats, such as damp areas, forests, pastures, gardens, and lawns, preferring fine gravel and sandy soil.[1][40] Colonies can also be spotted around light bushland. Their preferred natural habitats include woodlands, dry open forests, grasslands, and rural areas, and less common in urban areas.[26][40][41] Their nests are mounds built from finely granular gravel, soil, and pebbles, measuring 20 to 60 cm (8 to 24 in) in diameter and can be as tall as 0.5 m (20 in) in height.[42][43] Two types of nests for this species have been described, one being a simple nest with a noticeable shaft inside, the other being a complex structure surrounded by a mound.[44] These ants use the sun's warmth by decorating their nests with dry materials that heat in a quick duration, providing the nest with solar energy traps.[4][45] They decorate their nests with seeds, soil, charcoal, stones, sticks, and even small invertebrate corpses. They also camouflage their nests by covering them with leaf litter, debris, and long grass.[44] Nests can be found hidden under rocks, where queens most likely form their colonies, or around small piles of gravel, instead.[46] Their range in southern Australia, like other regional ant species, appears like that of a relict ant. Jack jumpers have been found in dry sclerophyll forests, at elevations ranging from 121 to 1,432 m (397 to 4,698 ft), averaging 1,001 m (3,284 ft).[47] Rove beetles in the genus Heterothops generally thrive in jack jumper nests and raise their brood within their chambers,[48] and skinks have been found in some nests.[49]

Populations are dense in the higher mountain regions of Tasmania.[1] Widespread throughout the state, their presence is known on King Island, located north-west from Tasmania.[50] The ant prefers rural areas, found in warm, dry, open eucalypt woodlands; the climate provides the ant with isolation and warmth. This environment also produces the ant's food, which includes nectar and invertebrate prey. In suburban areas, this ant is found in native vegetation, and uses rockeries, cracks in concrete walls, dry soil, and grass to build nests. One study found suburbs with voluminous vegetation cover such as Mount Nelson, Fern Tree and West Hobart host jack jumper populations, while the heavily urbanised suburbs of North Hobart and Battery Point, do not.[4]

Pest control of the jack jumper ant is successful in maintaining their populations around suburban habitats. Chemicals such as bendiocarb, chlorpyrifos, diazinon, and permethrin are effective against them.[51] Spraying of Solfac into nests is an effective way of controlling nests if they are in a close range of areas with considerable amounts of congestion and human activity. Pouring carbon disulfide into nest holes and covering entrances up with soil is another method of removing colonies.[52] The Australian National Botanic Gardens have an effective strategy of marking and maintaining jack jumper nests.[53]

Behaviour and ecology

[edit]

Primarily diurnal, workers search for food during the day until dusk.[1][4] They are active during warmer months, but are dormant during winter.[54] Fights between these ants within the same colony is not uncommon.[4] They are known for their aggression towards humans, attraction to movement, and well developed vision, being able to observe and follow intruders from 1 m (1.1 yd) away.[54][55][56] This species is an accomplished jumper, with leaps ranging from 2 to 3 in (51 to 76 mm).[27] William Morton Wheeler compared jack jumper ants to "Lilliputian cavalry galloping to battle" when disturbed, due to their jumping behaviour.[9] He further wrote that they also made a ludicrous appearance as they emerge from their nests, in a series of short hops.

While no studies have established whether or not these ants contain alarm pheromones, their relative Myrmecia gulosa is capable of inducing territorial alarm using pheromones. If proven, this would explain their ability to attack en masse.[4][57] Foraging workers are regularly observed on the inflorescences of Prasophyllum alpinum (mostly pollinated by wasps of the subfamily Ichneumonidae).[58] Although pollinia are often seen in the ants' jaws, they have a habit of cleaning their mandibles on the leaves and stems of nectar-rich plants before moving on, preventing pollen exchange.[58] Whether jack jumper ants contribute to pollination is unknown.[4]

Prey

[edit]

Unlike many other ants that use scent to forage for food, jack jumpers use their sight to target their prey, using rapid movements of the head and body to focus on their prey with their enlarged eyes.[54][59] Like other bull ants, they are solitary when they forage, but only workers perform this role. These ants are omnivores[26] and scavengers, typically foraging in warmer temperatures.[1] They deliver painful stings, which are effective in both killing prey and deterring predators.[60] Jack jumpers have smooth stingers, thus can sting indefinitely.[61] Jack jumper ants are skilled hunters, partially due to their excellent vision; they can even kill and devour wasps and bees.[62] They also kill and eat other ants, such as carpenter ants (Camponotus)[62] and feed on sweet floral secretions and other sugar solutions. They often hunt for spiders, and sometimes follow their prey for a short distance, usually with small insects and small arthropods.[4] Jack jumper ants, alongside M. simillima, have been given frozen houseflies (Musca domestica) and blowflies (Calliphoridae) as food under testing conditions.[63] The ants have been observed to run and leap energetically at flies when they land, particularly on Acacia shrubs, plants, or trees.[64] Jack jumpers and other Myrmecia ants prey on insects such as cockroaches and crickets.[65]

Mature adult ants of this species mostly eat sweet substances, so dead insects they find are given to their larvae.[66] However, larvae are only fed insects when they have reached a particular size.[67] Workers mostly collect small insects, sap-sucking insects along with the honeydew, which is taken to their nests to feed their young.[26] Observations have been made of fly predation by jack jumper ants; they only attack the smaller fly species and ignore larger ones.[68]

Predators and parasites

[edit]Blindsnakes of the family Typhlopidae are known to consume Myrmecia broods, although smaller blindsnakes avoid them since they are vulnerable to their stings.[69] Predatory invertebrates such as assassin bugs and redback spiders prey on jack jumpers and other Myrmecia ants. Thorny devils and echidnas, particularly the short-beaked echidna (Tachyglossus aculeatus) hunt jack jumper ants, eating their larvae and eggs.[70] Nymphs of the assassin bug species Ptilocnemus lemur lure these ants by trying to make the ant sting them.[71][72] The jack jumper ant is a host to the parasite gregarines (Gregarinasina).[73] Ants that host this parasite change colour from their typical black appearance to brown. This was discovered when brown jack jumpers were dissected and found to have Gregarinasina spores, while black jack jumpers showed no spores.[73] If it is present in large numbers, the parasite interferes with the normal darkening of the cuticles while the ant is in its pupal stage.[73] The cuticle softens due to the gregarine parasite.[74]

Lifecycle

[edit]Like every ant, the life of a jack jumper ant starts from an egg. If the egg is fertilised, the ant will be a female (diploid); if not, it will become a male (haploid).[75] They develop through complete metamorphosis, meaning that they pass through larval and pupal stages before emerging as an adult.[76] Cocoons that are isolated from the colony are able to shed their pupal skin before hatching, allowing themselves to advance to full pigmentation.[77] Pupae can also eclose (emerge from their pupal stage) without assistance from other ants.[63] Once born, jack jumper ants can identify distinct tasks, an obvious primitive trait Myrmecia ants are known for.[78]

Based on observations of six worker ants, the average life expectancy of the jack jumper is around 1.3 years, but workers were shown to live as little as 1.12 years or as long as 1.6, with the queen living much longer than the workers at 10 years or more.[40][79] These data give a life expectancy of 401–584 days, with an average of 474 days.[80] Egg clumping is common, as observed in laboratory colonies.[63] These clumps are often carried by worker ants, and these clumps would contain two to 30 eggs, without any larvae to hold them together.[63] This confirms that eggs from jack jumper colonies do not always lie singly apart.[81] George C. Wheeler and Jeanette Wheeler (1971) studied and described larvae collected from New South Wales and South Australia. They noted that very young larvae of the jack jumper were 2.4 mm (0.094 in) in length, with two types of body hair. They also described young larvae (matured from very young larvae) at 2.7 mm (0.11 in), but with similar body characteristics to mature larvae, at 12.5 mm (0.49 in).[82]

Reproduction

[edit]

Queens are polyandrous, meaning that queens can mate more than once; queens mate with one to nine males during a nuptial flight, and the effective number of mates per queen ranges from 1.0 to 11.4.[83][84] Most queen ants only mate with one or two males.[85] If the number of available male mates increases, the number of effective matings per queen decreases.[83] Colonies are polygynous, meaning that a colony may house multiple queens; one to four queens typically inhabit a colony, and in multiple-queen colonies, the egg-laying queens are unrelated to one another.[85][86] Based on a study, 11 of the 14 colonies tested were polygynous (78.57%), showing that this is common in jack jumper colonies.[83] When the queen establishes a nest after mating, she will hunt for food to feed her young, making her semiclaustral.[87] Nests can hold as few as 500 ants or as many as 800 to 1,000.[88][89] Excavated nests typically have populations ranging from 34 to 344 individuals.[44] Jack jumper ant workers are gamergates, having the ability to reproduce in colonies with or without queens.[90][91]

Colonies are mainly polygynous with polyandrous queens, but[92] polyandry in jack jumper colonies is low in comparison to other Myrmecia ants, but it is comparable to M. pyriformis ants.[93] In 1979, Craig and Crozier investigated the genetic structure of jack jumper ant colonies, and although queens are unrelated to each other, the occurrence of related queens in a single colony was possible.[94] During colony foundation, suggestions exist of dependent colony foundation in jack jumper queens, although independent colony foundations can occur, as the queens do have fully developed wings and can fly.[85] Isolation by distance patterns have been recorded, specifically where nests that tend to be closer to each other were more genetically similar in comparison to other nests farther away.[85]

As colonies closer to each other are more genetically similar, independent colony foundation is most likely associated with nuptial flight if they disperse far from genetically similar colonies they originate from.[85] Inseminated queens could even seek adoption into alien colonies if a suitable nest site area for independent colony foundation is restricted or cannot be carried out, known as the nest-site limitation hypothesis.[85][95] Some queens could even try to return to their nests that they came from after nuptial flight, but end in another nest, in association that nests nearby will be similar to the queen's birth nest.[85]

Genetics

[edit]The jack jumper ant genome is contained on a single pair of chromosomes (males have just one chromosome, as they are haploid). This is the lowest number known (indeed possible) for any animal, a number shared with the parasitic roundworm Parascaris equorum univalens.[96][97] Jack jumper ants are taxonomically discussed as a single biological species in the Myrmecia pilosula species complex.[1][8] The ant has nine polymorphic loci, which yielded 67 alleles.[98]

Interaction with humans

[edit]History

[edit]The earliest known account of ant sting fatalities in Australia was first recorded in 1931; two adults and an infant girl from New South Wales died from ant stings, possibly from the jack jumper ant or M. pyriformis.[99] Thirty years later, another fatality was reported in 1963 in Tasmania.[100] Historical and IgE results have suggested these two species or perhaps another species were responsible for all recorded deaths.[101]

Between 1980 and 2000, four deaths have been recorded,[40] all in Tasmania and all due to anaphylactic shock.[24][102][103][b] All known patients who died from jack jumper stings were at least 40 years old and had cardiopulmonary comorbidities.[101][104] Severe laryngeal oedema and coronary atherosclerosis were detected in most of the autopsies of those who died. Most of the victims died within 20 minutes after being stung.[101] Prior to any desensitisation program being established, the fatality rate was one person every four years from the sting.[105]

Before venom immunotherapy, whole body extract immunotherapy was widely used due to its apparent effectiveness, and it was the only immunotherapy used on ants.[106][107] However, fatal failures were reported and this led to scientists researching for alternative methods of desensitisation.[108] Whole body extract immunotherapy was later proven to be ineffective, and venom immunotherapy was found to be safe and effective to use.[109] Paul Clarke first drew medical attention to the jack jumper ant in 1986, and before this, there had been no history of records of allergic reactions or study on their sting venom.[110] The identification of venom allergens began in the early 1990s in preparation for therapeutic use.[111] Whole body extracts were first used to desensitize patients, but it was found to be ineffective and later withdrawn.[112] Venom immunotherapy was shown to reduce the risk of systemic reactions, demonstrating that immunotherapy can be provided for ant-sting allergies.[107]

In 2003, Professor Simon Brown established the jack jumper desensitisation program, although the program is at risk of closure.[113][needs update] Since the establishment of the program, no death has been recorded since 2003.[needs update] However, the ant may be responsible for the death of a Bunbury man in 2011.[114]

Incidence

[edit]The extent of the jack jumper sting problem differs among areas. Allergy prevalence rates are significantly lower in highly urbanised areas and much higher in rural areas. These ants represent a hazard towards people in the southern states of Australia, due to a high proportion of the population having significant allergies to the ant's sting.[24][115][116] The ant is a significant cause of major insect allergies,[117] responsible for most anaphylaxis cases in Australia,[24] and rates of anaphylaxis are twice those of honeybee stings.[118] One in three million annually die of general anaphalaxis in Australia alone.[119] Over 90% of Australian ant venom allergies have been caused by the jack jumper.[120]

The ant is notorious in Tasmania, where most fatalities have been recorded.[29] In 2005, over a quarter of all jack jumper sting incidents were sustained in Tasmania; excessive in comparison to its 2006 population of only 476,000 people.[121][122] Jack jumper stings are the single most common cause of anaphylaxis in patients at the Royal Hobart Hospital.[123] The ant has also been a major cause of anaphylaxis outside Tasmania, notably around Adelaide and the outskirts of Melbourne, while cases in New South Wales and Western Australia have been more distributed.[124] One in 50 adults have been reported to suffer anaphylaxis due to the jack jumper or other Myrmecia ants.[24]

Venom

[edit]The jack jumper ant and its relatives in the genus Myrmecia are among the most dangerous ant genera and have fearsome reputations for their extreme aggression; Guinness World Records certifies the ant Myrmecia pyriformis as the world's most dangerous ant.[55][125] The jack jumper have been compared to other highly aggressive ant species, such as Brachyponera chinensis, Brachyponera sennaarensis, and the red imported fire ant (Solenopsis invicta).[126] The retractable sting is located in their abdomen, attached to a single venom gland connected by the venom sac, which is where the venom is accumulated.[127][128] Exocrine glands are known in jack jumpers, which produce the venom compounds later used to inject into their victims.[129] Their venom contains haemolytic and eicosanoid elements and histamines. It contains a range of active ingredients and enzymatic activity, which includes phospholipase A2 and B, hyaluronidase, acid and alkaline phosphatase.[123][130] The venom of the ant also contains several peptides; one being pilosulin 1, which causes cytotoxic effects, pilosulin 2, which has antihypertensive properties and pilosulin 3, which is known to be a major allergen.[131][132] Other pilosulins include pilosulin 4 and pilosulin 5.[131][133] The peptides have known molecular weights.[134][135] The LD50 (lethal dose) occurs at a lower concentration than for melittin, a peptide found in bee venom.[136][137] Its LD50 value is 3.6 mg/kg (injected intravenously in mice).[138]

Loss of cell viability in the jack jumper's venom was researched through cytometry, which measures the proportions of cells that glow in the presence of fluorescent dye and 7-Aminoactinomycin D. Examinations of the rapidly reproducing Epstein–Barr B-cells showed that the cells lost viability within minutes when exposed to pilosulin 1. Normal white blood cells were also found to alter easily when exposed to pilosulin 1. However, partial peptides of pilosulin 1 were less efficient at lowering cell viability; the residue 22 N-terminal plays a critical role in the cytotoxic activity of pilosulin 1.[136]

20 percent of jack jumper ants have an empty venom sac, so failure to display a sting reaction should not be interpreted as a loss of sensitivity.[38] Substantial amounts of ant venom have been analysed to characterise venom components, and the jack jumper has been a main subject in these studies.[139] An East Carolina University study which summarised the knowledge about ant stings and their venom showed that only the fire ant and jack jumper had the allergenic components of their venom extensively investigated.[140] These allergenic components include peptides found as heterodimers, homodimers and pilosulin 3.[140] Only six Myrmecia ants, including the jack jumper, are capable of inducing IgE antibodies.[141] Due to the vast differentiation of venom produced in each Myrmecia species, and other species sharing similar characteristics to the jack jumper ant, diagnosing which ant is responsible for an anaphylactic reaction is difficult.[114] A review of a patient's history with allergies while identifying a positive result of venom specific IgE levels helps to identify the species of ant that caused a reaction.[101]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]Reactions to the ants sting show similar symptoms to fire ant stings; namely local swelling which lasts for several days, and swelling of the lips, face and eyes may occur from a minor allergic reaction.[142] Other common symptoms include watering of the eyes and nose, and hives or welts will begin to develop. Headaches, anxiety and flushing may also occur.[142] Jack jumpers, bees and wasps are the most common causes of anaphylaxis from insect stings.[143][144][145] People most commonly feel a sharp pain after these stings, similar to that from an electric shock.[54] Some patients develop a systemic skin reaction after being stung.[146] Localised envenomation occurs with every sting, but severe envenoming only occurs if someone has been stung many times (as many as 50 to 300 stings in adults).[147] The heart rate increases, and blood pressure falls rapidly.[148] Most people will only experience mild skin irritation after being stung.[149] Those who suffer from a severe allergic reaction will show a wide variety of symptoms. This includes difficulty breathing and talking, the tongue and throat will swell up, and coughing, chest tightness, abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting may occur. Others may lose consciousness and collapse (sometimes people may not collapse), and confusion. Children who get stung will show symptoms such as floppiness and paleness if a severe allergic reaction occurs.[142]

In individuals allergic to the venom (about 2–3% of the population), a sting sometimes causes anaphylactic shock.[104][150][151][152] In comparison to other insects such as the western honeybee (Apis mellifera) and the European wasp (Vespula germanica), their rates are only 1.4% and 0.6%. The annual sting exposure rates for the jack jumper ant, Western honeybee and European wasp are 12%, 7% and 2%.[24] The median time from sting to cardiac arrest is 15 minutes, but the maximum period is around three hours.[24][120] The ant allergy does not disappear; people with jack jumper allergies will most likely suffer from another allergic reaction if re-stung.[24] Approximately 70 percent of patients with a history of systemic reaction to the ant's sting have another reaction when stung again.[38] In comparison, systemic reaction figures for Apis mellifera and Vespula germanica after being stung show a rate of 50% and 25%.[56][153] About half of these reactions were life-threatening and occurred predominantly in people who had had previous incidents with the sting.[38] Anaphylaxis in jack jumper ant stings are not rare; 2.9% of 600 residents from semi-rural Victoria had allergic reactions to the ant's sting, according to a questionnaire.[154] The sensitivity to stings is persistent for many years.[153]

In 2011, an Australian ant allergy venom study was conducted, with the goal of determining which native Australian ants were associated with ant sting anaphylaxis. It showed that the jack jumper ant was responsible for the majority of patients' reactions to stings from ants of genus Myrmecia. Of the 265 patients who reacted to such a sting, 176 were from the jack jumper, 15 from M. nigrocincta and three from M. ludlowi, while 56 patients had reacted to other Myrmecia ants. The study concluded that four native species of Australian ants caused anaphylaxis. Apart from Myrmecia species, the green-head ant (Rhytidoponera metallica) was also responsible for several systemic reactions.[124][155]

Most people recover uneventfully following a mild local reaction and up to about 3% of individuals suffer a severe localised reaction.[114] Most individuals who suffer from severe localised reactions will most likely encounter another reaction if stung again.[38] Fatalities are rare, and venom immunotherapy can prevent fatalities.[114][156]

First aid and emergency treatment

[edit]

If no signs of an allergic reaction are present, an ice pack or commercially available sprays are used to relieve the pain.[55] Stingose is also recommended to treat a jack jumper sting.[53] Other treatments include washing the stung area with soap and water, and if continuous pain remains for several days, antihistamine tablets are taken for one to three days.[157]

Emergency treatment is needed in a case of a severe allergic reaction. Before calling for help, have the person lie down and elevate their legs.[114] Depending on a patient's needs, they will be given an EpiPen or an Anapen to use in case they are stung.[158] In a scenario of experiencing anaphylaxis, further doses of adrenaline and intravenous infusions may be required. Some with severe anaphylaxis may suffer cardiac arrest and will need resuscitation.[114] Inhalers may additionally be used in case a victim has asthma and experiences a reaction from a sting.[147] The use of ACE inhibitors is not recommended, as it is known to increase the risk of anaphylaxis.[104] Medications like antihistamines, H2 blockers, corticosteroids and anti-leukotrienes have no effect on anaphylaxis.[38]

There are several bush remedies used to treat jack jumper stings (and any other Myrmecia sting). The young tips of a bracken fern provide a useful bush remedy to treat jack jumper stings, discovered and currently used by indigenous Australians. The tips are rubbed on the stung area, and may relieve the local pain after getting stung.[159] Another plant used as a bush remedy is Carpobrotus glaucescens (known as angular sea-fig or pigface).

Desensitisation and prevention

[edit]

Desensitisation (also called allergy immunotherapy) to the jack jumper sting venom has shown effectiveness in preventing anaphylaxis,[156][160] but the standardisation of jack jumper venom is yet to be validated.[161] Unlike bee and wasp sting immunotherapy, jack jumper immunotherapy lacks funding and no government rebate is available.[162][163] Venom is available; however, no commercial venom extract is available that can be used for skin testing.[38] Venom extract is only available through the Therapeutic Goods Administration Special Access Scheme.[112]

The Royal Hobart Hospital offers a desensitisation program for patients who have had a severe allergic reaction to a jack jumper sting.[40] However, the program may face closure due to budget cuts.[113][164] Professor Simon Brown, who founded the program, commented, "Closing the program will leave 300 patients hanging in the lurch".[113] There is a campaign to make the program available in Victoria.[165] The Royal Adelaide Hospital runs a small-scale program that desensitises patients to the ant's venom.[25]

Patients are given an injection of venom under the skin in small amounts. During immunotherapy, the first dose is small, but will gradually increase per injection. This sort of immunotherapy is designed to change how the immune system reacts to increased doses of venom entering the body.[156]

Follow-ups of untreated people over thirty with a history of severe allergic reactions would greatly benefit from venom immunotherapy.[166] Both rapid and slow doses can be done safely during immunotherapy.[167] The efficacy (capacity to induce a therapeutic effect) of ant venom immunotherapy is effective in reducing systemic reactions in comparison to placebo and whole body extract immunotherapy, where patients were more likely to suffer from a systemic reaction.[106][156][166] Ultrarush initiation of insect immunotherapy may be used, but results show higher risks of allergic reactions.[168] Despite immunotherapy being successful, only ten percent of patients do not have any response to desensitisation.[169]

It is suggested that people should avoid jack jumpers, but this is difficult to do. Closed footwear (boots and shoes) along with socks reduce the chances of encountering a sting, but wearing thongs or sandals will put the person at risk. With this said, they are still capable of stinging through fabric, and can find their way through gaps in clothing.[38] Most stings occur when people are gardening, so taking extra caution or avoiding gardening altogether is recommended.[4] People can also avoid encountering jack jumpers by moving to locations where jack jumper populations are either low or absent, or eliminate nearby nests.[112] Since Myrmecia ants have different venoms, people who are allergic to them are advised to stay away from all Myrmecia ants, especially to ones they have not encountered before.[101]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Despite evidence of their presence in Queensland, CSIRO claim their presence in Queensland is yet to be verified.[39]

- ^ The total number of deaths from this 20 year period due to the ant could be higher. One account reports of another fatality in Tasmania and one in New South Wales, although these two deaths may have been caused by a sting from M. pyriformis.[101]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Brown, William (1953). "Revisionary notes on the ant genus Myrmecia of Australia" (PDF). Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology. 111 (6). Cambridge, Massachusetts: 1–35.

- ^ Johnson, Norman F. (19 December 2007). "Myrmecia pilosula Smith". Hymenoptera Name Server version 1.5. Columbus, Ohio, USA: Ohio State University. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ^ AntWeb. "Specimen: Casent0902800 Myrmecia pilosula". antweb.org. The California Academy of Sciences. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Evans, Maldwyn J. (2008). The Preferred Habitat of the Jack Jumper Ant (Myrmecia pilosula): a Study in Hobart, Tasmania. Invertebrate Biology (Report). Hobart.

- ^ Atkinson, Ann; Moore, Alison (2010). Macquarie Australian encyclopedic dictionary (2nd ed.). Sydney: Macquarie Dictionary Publishers. p. 914. ISBN 978-1-876429-83-6. OCLC 433042647.

- ^ a b Smith 1858, p. 146.

- ^ a b Department of the Environment (8 April 2014). "Species Myrmecia pilosula Smith, 1858". Australian Biological Resources Study: Australian Faunal Directory. Canberra: Government of Australia. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Clark, John (1951). The Formicidae of Australia (Volume 1). Subfamily Myrmeciinae (PDF). Melbourne: Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation, Australia. pp. 202–204.

- ^ a b Wheeler, William Morton (1922). "Observations on Gigantiops destructor Fabricius and Other Leaping Ants". Biological Bulletin. 42 (4): 185–201. doi:10.2307/1536521. JSTOR 1536521.

- ^ Clark, John (1927). "The ants of Victoria. Part III" (PDF). Victorian Naturalist (Melbourne). 44: 33–40.

- ^ Clark, John (1943). "A revision of the genus Promyrmecia Emery (Formicidae)" (PDF). Memoirs of the National Museum of Victoria. 13: 83–149. ISSN 0083-5986.

- ^ Brown, William L. Jr. (1953). "Characters and synonymies among the genera of ants Part I". Breviora. 11 (1–13). ISSN 0006-9698.

- ^ Shattuck, Steven O. (2000). Australian Ants: Their Biology and Identification. Vol. 3. Collingwood: CSIRO Publishing. p. 121. ISBN 978-0-643-06659-5.

- ^ Smith 1858, p. 93.

- ^ Roger, Julius (1861). "Myrmicologische Nachlese" (PDF). Berliner Entomologische Zeitschrift (in German). 5: 163–174.

- ^ a b Emery, Carlo (1911). "Hymenoptera. Fam. Formicidae. Subfam. Ponerinae" (PDF). Genera Insectorum. 118: 1–125.

- ^ Crosland, M. W. J.; Crozier, R. H.; Imai, H. T. (February 1988). "Evidence for several sibling biological species centred on Myrmecia pilosula (F. Smith) (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)". Australian Journal of Entomology. 27 (1): 13. doi:10.1111/j.1440-6055.1988.tb01136.x.

- ^ Imai, Hirotami T.; Crozier, Ross H.; Taylor, Robert W. (1977). "Karyotype evolution in Australian ants". Chromosoma. 59 (4): 341–393. doi:10.1007/BF00327974. ISSN 1432-0886. S2CID 46667207.

- ^ Hirai, Hirohisa; Yamamoto, Masa-Toshi; Ogura, Keiji; Satta, Yoko; Yamada, Masaaki; Taylor, Robert W.; Imai, Hirotami T. (June 1994). "Multiplication of 28S rDNA and NOR activity in chromosome evolution among ants of the Myrmecia pilosula species complex". Chromosoma. 103 (3): 171–178. doi:10.1007/BF00368009. ISSN 1432-0886. PMID 7924619. S2CID 5564536.

- ^ Crozier, R.; Dobric, N.; Imai, H.T.; Graur, D.; Cornuet, J.M.; Taylor, R.W. (March 1995). "Mitochondrial-DNA Sequence Evidence on the Phylogeny of Australian Jack-Jumper Ants of the Myrmecia pilosula Complex" (PDF). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 4 (1): 20–30. Bibcode:1995MolPE...4...20C. doi:10.1006/mpev.1995.1003. PMID 7620633.

- ^ Hasegawa, Eisuke; Crozier, Ross H. (March 2006). "Phylogenetic relationships among species groups of the ant genus Myrmecia". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 38 (3): 575–582. Bibcode:2006MolPE..38..575H. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2005.09.021. PMID 16503279.

- ^ Ogata, Kazuo; Taylor, Robert W. (1991), "Ants of the genus Myrmecia Fabricius: a preliminary review and key to the named species (Hymenoptera: Formicidae: Myrmeciinae)" (PDF), Journal of Natural History, 25 (6): 1623–1673, Bibcode:1991JNatH..25.1623O, doi:10.1080/00222939100771021

- ^ Taylor, Robert W. (21 January 2015). "Ants with Attitude: Australian Jack-jumpers of the Myrmecia pilosula species complex, with descriptions of four new species (Hymenoptera: Formicidae: Myrmeciinae)" (PDF). Zootaxa. 3911 (4): 493–520. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.3911.4.2. hdl:1885/66773. PMID 25661627.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Brown, SG; Franks, RW; Baldo, BA; Heddle, RJ (January 2003). "Prevalence, severity, and natural history of jack jumper ant venom allergy in Tasmania". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 111 (1): 187–92. doi:10.1067/mai.2003.48. PMID 12532117.

- ^ a b Davies, Nathan (30 January 2015). "Angry ants on the march in SA — and can have fatal consequences". Adelaide Now. Retrieved 10 February 2015.

- ^ a b c d e "Myrmecia pilosula Smith, 1858". Atlas of Living Australia. Government of Australia. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- ^ a b c "The Naturalist. Stinging Ants. (Continued)". The Australasian. Melbourne, Victoria: National Library of Australia. 30 May 1874. p. 7. Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- ^ "Jack Jumper Allergy Program". Department of Health and Human Services. Government of Tasmania. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- ^ a b "The jack jumper – Tasmania's killer ant: 2012". ABC Hobart and the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery. ABC News. 12 February 2013. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- ^ Archibald, S.B.; Cover, S. P.; Moreau, C. S. (2006). "Bulldog Ants of the Eocene Okanagan Highlands and History of the Subfamily (Hymenoptera: Formicidae: Myrmeciinae)" (PDF). Annals of the Entomological Society of America. 99 (3): 487–523. doi:10.1603/0013-8746(2006)99[487:BAOTEO]2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Wilson, Edward O.; Hölldobler, Bert (17 May 2005). "The rise of the ants: A phylogenetic and ecological explanation". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 102 (21): 7411–7414. Bibcode:2005PNAS..102.7411W. doi:10.1073/pnas.0502264102. PMC 1140440. PMID 15899976.

- ^ Bolton, Barry (2003). Synopsis and classification of formicidae. Gainesville, FL.: American Entomological Institute. p. 132. ISBN 978-1-887988-15-5.

- ^ a b Crawley, W. Cecil (1926). "A Revision of some old Types of Formicidae" (PDF). Transactions of the Royal Entomological Society of London. 73 (3–4): 373–393. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2311.1926.tb02641.x.

- ^ Andersen, Alan N. (1991). The ants of southern Australia: a guide to the Bassian fauna. East Melbourne, Australia: CSIRO Publishing. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-19-550643-3.

- ^ a b Sutherland, Struan K. J.; Tibballs, James (2001). Australian animal toxins: the creatures, their toxins, and care of the poisoned patient (2nd ed.). South Melbourne: Oxford University Press. pp. 491–501. ISBN 978-0-19-550643-3.

- ^ Santschi, Felix (1928). "Nouvelles fourmis d'Australie". Bulletin de la Société Vaudoise des Sciences Naturelles. 56: 465–483.

- ^ Clark, John (1934). "Ants from the Otway Ranges" (PDF). Memoirs of the National Museum of Victoria. 8: 48–73. doi:10.24199/j.mmv.1934.8.03.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Jack Jumper Ant Allergy – a uniquely Australian problem". Australasian Society of Clinical and Immunology and Allergy (ASCIA). 2010. Archived from the original on 26 August 2014. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ^ a b "Jumping jacks: Myrmecia pilosula Smith". CSIRO Publishing. 18 September 2004. Archived from the original on 18 April 2019. Retrieved 14 February 2015.

- ^ a b c d e "Jack Jumper Ants Myrmecia pilosula complex of species (also known as jumper ants or hopper ants)" (PDF). Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment. Government of Tasmania. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- ^ Miller, L.J.; New, T.R. (February 1997). "Mount Piper grasslands: pitfall trapping of ants and interpretation of habitat variability". Memoirs of the Museum of Victoria. 56 (2): 377–381. doi:10.24199/j.mmv.1997.56.27. ISSN 0814-1827. LCCN 90644802. OCLC 11628078.

- ^ Whinam, J.; Hope, G. (2005). "The Peatlands of the Australasian Region" (PDF). Mires. From Siberia to Tierra del Fuego. Stapfia: 397–433.

- ^ Russell, Richard C.; Domenico, Otranto; Wall, Richard L. (2013). The Encyclopedia of Medical and Veterinary Entomology. CABI. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-78064-037-2.

- ^ a b c Gray, B. (March 1974). "Nest structure and populations of Myrmecia (Hymenoptera: Formicidae), with observations on the capture of prey". Insectes Sociaux. 21 (1): 107–120. doi:10.1007/BF02222983. S2CID 11886883.

- ^ Hölldobler & Wilson 1990, p. 373.

- ^ Pesek, Robert D.; Lockey, Richard F. (2013). "Management of Insect Sting Hypersensitivity: An Update". Allergy, Asthma & Immunology Research. 5 (3): 129–37. doi:10.4168/aair.2013.5.3.129. PMC 3636446. PMID 23638310.

- ^ AntWeb. "Species: Myrmecia pilosula". antweb.org. The California Academy of Sciences. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- ^ Hermann, Henry R. (1982). Social Insects Volume 3. Oxford: Elsevier Science. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-12-342203-3.

- ^ Loveridge, A. (1934). "Australian reptiles in the Museum of Comparative Zoology, Cambridge, Massachusetts". Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology. 77: 243–283. ISSN 0027-4100. LCCN 12032997//r87. OCLC 1641426.

- ^ Forel, Auguste H. (1913). "Fourmis de Tasmanie et d'Australie récoltées par MM. Lea, Froggatt, etc" (PDF). Bulletin de la Société Vaudoise des Sciences Naturelles. 49: 173–195. doi:10.5281/ZENODO.14158.

- ^ Williams, Margaret A. (February 1991). "Insecticidal Control of Myrmecia Pilosula F. Smith (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)". Australian Journal of Entomology. 30 (1): 93–94. doi:10.1111/j.1440-6055.1991.tb02202.x.

- ^ "Household Insect Pests". Brighton Southern Cross. Brighton: National Library of Australia. 15 October 1910. p. 2. Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- ^ a b "Jack Jumper Ants Strategy". Australian National Botanic Gardens. Government of Australia. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- ^ a b c d Williamson, Brett (10 July 2013). "Jumping ants ready to deliver a nasty sting for South Australian residents". 891 ABC Adelaide. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 13 September 2014.

- ^ a b c Australian Museum (30 January 2014). "Animal Species: Bull ants". Retrieved 26 August 2014.

- ^ a b "Allergic reactions to insect bites and stings" (PDF). MedicineToday. 2004. p. 20. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- ^ Frehland, E; Kleutsch, B; Markl, H (1985). "Modelling a two-dimensional random alarm process". Bio Systems. 18 (2): 197–208. Bibcode:1985BiSys..18..197F. doi:10.1016/0303-2647(85)90071-1. PMID 4074854.

- ^ a b Abrol, D.P. (2011). Pollination Biology: Biodiversity Conservation and Agricultural Production (2012 ed.). Springer. p. 288. ISBN 978-94-007-1941-5.

- ^ Greiner, Birgit; Narendra, Ajay; Reid, Samuel; Dacke, Marie; Ribi, Wili A.; Zeil, Jochen (23 October 2017). "Eye structure correlates with distinct foraging-bout timing in primitive ants". Current Biology. 17 (20): R879–R880. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2007.08.015. hdl:1885/56345. PMID 17956745.

- ^ "Newsletter – North Sydney Council – NSW Government" (PDF). North Sydney Council. Government of New South Wales. Retrieved 21 August 2014.

- ^ "Ants are everywhere". CSIRO Publishing. 22 February 2006. Archived from the original on 1 November 2014. Retrieved 2 September 2014.

- ^ a b Moffett, Mark W. (May 2007). "Bulldog Ants". National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 23 June 2008. Retrieved 21 August 2014.

- ^ a b c d Crosland, Michael W. J.; Crozier, Ross H.; Jefferson, E. (November 1988). "Aspects of the Biology of the Primitive Ant Genus Myrmecia F. (Hymenoptera: Formicdae)" (PDF). Australian Journal of Entomology. 27 (4): 305–309. doi:10.1111/j.1440-6055.1988.tb01179.x. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 August 2014. Retrieved 19 August 2014.

- ^ Beattie, Andrew James (1985). The Evolutionary Ecology of Ant-Plant Mutualisms (Cambridge Studies in Ecology Series ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-521-25281-2.

- ^ Hnederson, Alan; Henderson, Deanna; Sinclair, Jesse (2008). Bugs alive: a guide to keeping Australian invertebrates. Melbourne: Museum Victoria. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-9758370-8-5.

- ^ "Formicidae Family". CSIRO Publishing. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- ^ Freeland, J. (1958). "Biological and social patterns in the Australian bulldog ants of the genus Myrmecia". Australian Journal of Zoology. 6 (1): 1–18. doi:10.1071/ZO9580001.

- ^ Archer, M. S.; Elgar, M. A. (September 2003). "Effects of decomposition on carcass attendance in a guild of carrion-breeding flies". Medical and Veterinary Entomology. 17 (3): 263–271. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2915.2003.00430.x. PMID 12941010. S2CID 2459425.

- ^ Webb, Jonathan K.; Shine, Richard (June 1993). "Prey-size selection, gape limitation and predator vulnerability in Australian blindsnakes (Typhlopidae)". Animal Behaviour. 45 (6): 1117–1126. doi:10.1006/anbe.1993.1136. S2CID 53162363.

- ^ Spencer, Chris P.; Richards, Karen (2009). "Observations on the diet and feeding habits of the short-beaked echidna (Tachyglossus aculeatus) in Tasmania" (PDF). The Tasmanian Naturalist. 131: 36–41. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 March 2015.

- ^ Ceurstemont, Sandrine (17 March 2014). "Zoologger: Baby assassin bugs lure in deadly ants". New Scientist. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ^ Bulbert, Matthew W.; Herberstein, Marie Elisabeth; Cassis, Gerasimos (March 2014). "Assassin bug requires dangerous ant prey to bite first". Current Biology. 24 (6): R220–R221. Bibcode:2014CBio...24.R220B. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2014.02.006. PMID 24650903.

- ^ a b c Crosland, Michael W. J. (1 May 1988). "Effect of a Gregarine Parasite on the Color of Myrmecia pilosula (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)". Annals of the Entomological Society of America. 81 (3): 481–484. doi:10.1093/aesa/81.3.481.

- ^ Moore, Janice (2002). Parasites and the Behavior of Animals (Oxford Series in Ecology and Evolution) (1st ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 172. ISBN 978-0-19-514653-0.

- ^ Hölldobler & Wilson 1990, p. 183.

- ^ Hadlington, Phillip W.; Beck, Louise (1996). Australian Termites and Other Common Timber Pests. UNSW Press. p. 102. ISBN 978-0-86840-399-1.

- ^ Burghardt, Gordon M.; Bekoff, Marc (1978). The Development of behavior: comparative and evolutionary aspects. University of Michigan: Garland STPM Press. p. 83. ISBN 978-0-8240-7015-1.

- ^ Veeresh, G.K.; Mallik, B.; Viraktamath, C.A. (1990). Social insects and the environment. Leiden: E.J. Brill. p. 311. ISBN 978-90-04-09316-4.

- ^ Hölldobler & Wilson 1990, p. 169.

- ^ Schmid-Hempel, Paul (1998). Parasites in Social Insects. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-691-05923-5.

- ^ Wilson, Edward O. (1971). The Insect Societies (illustrated, reprint ed.). Harvard, Massachusetts: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-674-45495-8.

- ^ Wheeler, George C.; Wheeler, Jeanette (1971). "Ant larvae of the subfamily Myrmeciinae (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)". Pan-Pacific Entomologist. 47 (4): 245–56.

- ^ a b c Qian, Zeng-Qiang; Schlick-Steiner, Birgit C.; Steiner, Florian M.; Robson, Simon K.A.; Schlüns, Helge; Schlüns, Ellen A.; Crozier, Ross H. (17 September 2011). "Colony genetic structure in the Australian jumper ant Myrmecia pilosula". Insectes Sociaux. 59 (1): 109–117. doi:10.1007/s00040-011-0196-4. ISSN 1420-9098. S2CID 17183074.

- ^ Hölldobler & Wilson 1990, p. 187.

- ^ a b c d e f g Qian, Zengqiang (2012). Evolution of social structure in the ant genus Myrmecia fabricius (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) (PDF). Townsville: PhD thesis, James Cook University. pp. 1–96.

- ^ Hölldobler & Wilson 1990, p. 186.

- ^ Haskins, Caryl P.; Haskins, Edna F. (December 1950). "Notes on the biology and social behavior of the archaic Ponerine ants of the genera Myrmecia and Promyrmecia". Annals of the Entomological Society of America. 43 (4): 461–491. doi:10.1093/aesa/43.4.461.

- ^ Hölldobler & Wilson 1990, p. 161.

- ^ Brian, Michael Vaughan (1978). Production Ecology of Ants and Termites. Vol. 13. Cambridge University Press. p. 335. ISBN 978-0-521-21519-0. ISSN 0962-5968.

- ^ Hölldobler & Wilson 1990, p. 190.

- ^ Trager, James C (1 December 1989). Advances in Myrmecology. Brill Academic Pub. p. 183. ISBN 978-90-04-08475-9.

- ^ Kellner, K; Trindl, A; Heinze, J; D'Ettorre, P (June 2007). "Polygyny and polyandry in small ant societies". Molecular Ecology. 16 (11): 2363–9. Bibcode:2007MolEc..16.2363K. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294x.2007.03297.x. PMID 17561897. S2CID 38969626.

- ^ Sanetra, M. (2011). "Nestmate relatedness in the Australian ant Myrmecia pyriformis Smith, 1858 (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)". Myrmecological News. 15: 77–84.

- ^ Craig, R.; Crozier, H. (March 1979). "Relatedness in the polygynous ant Myrmecia pilosula". Society for the Study of Evolution. 33 (1): 335–341. doi:10.2307/2407623. ISSN 0014-3820. JSTOR 2407623. PMID 28568175.

- ^ Herbers, Joan M. (July 1986). "Nest site limitation and facultative polygyny in the ant Leptothorax longispinosus". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 19 (2): 115–122. doi:10.1007/BF00299946. S2CID 39599080.

- ^ Crosland, M.W.J.; Crozier, R.H. (1986). "Myrmecia pilosula, an ant with only one pair of chromosomes". Science. 231 (4743): 1278. Bibcode:1986Sci...231.1278C. doi:10.1126/science.231.4743.1278. JSTOR 1696149. PMID 17839565. S2CID 25465053.

- ^ Imai, Hirotami T.; Taylor, Robert W. (December 1989). "Chromosomal polymorphisms involving telomere fusion, centromeric inactivation and centromere shift in the ant Myrmecia (pilosula) n=1". Chromosoma. 98 (6): 456–460. doi:10.1007/BF00292792. ISSN 1432-0886. S2CID 40039115.

- ^ Qian, Zeng-Qiang; Sara Ceccarelli, F.; Carew, Melissa E.; Schlüns, Helge; Schlick-Steiner, Birgit C.; Steiner, Florian M. (May 2011). "Characterization of Polymorphic Microsatellites in the Giant Bulldog Ant, Myrmecia brevinoda and the jumper ant, M. pilosula". Journal of Insect Science. 11 (71): 71. doi:10.1673/031.011.7101. ISSN 1536-2442. PMC 3281428. PMID 21867438.

- ^ Cleland, J.B. (1931). "Insects in Their Relationship to Injury and Disease in Man in Australia. Series III". The Medical Journal of Australia. 2: 711. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.1931.tb102384.x. S2CID 204032015.

- ^ Trica, J.C. (24 October 1964). "Insect Allergy in Australia: Results of a Five-Year Survey". The Medical Journal of Australia. 2 (17): 659–63. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.1964.tb109508.x. PMID 14213613. S2CID 8537870.

- ^ a b c d e f McGain, Forbes; Winkel, Kenneth D. (August 2002). "Ant sting mortality in Australia". Toxicon. 40 (8): 1095–1100. Bibcode:2002Txcn...40.1095M. doi:10.1016/S0041-0101(02)00097-1. PMID 12165310.

- ^ "Jumper Ants (Myrmecia pilosula species group)". Australian Venom Research Unit. University of Melbourne. Archived from the original on 11 January 2015. Retrieved 24 August 2014.

- ^ "Bull and Jumper Ants". Queensland Museum. Retrieved 24 August 2014.

- ^ a b c Brown, Simon G. A.; Wu, Qi-Xuan; Kelsall, G. Robert H.; Heddle, Robert J. & Baldo, Brian A. (2001). "Fatal anaphylaxis following jack jumper ant sting in southern Tasmania". Medical Journal of Australia. 175 (11): 644–647. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2001.tb143761.x. PMID 11837875. S2CID 2495334.

- ^ Guest, Annie (17 February 2005). "Vaccine underway in Tas' for 'Jack jumper' ant bite". The World Today. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 5 December 2014.

- ^ a b Piek, Tom (October 2013). Venoms of the Hymenoptera: Biochemical, Pharmacological and Behavioural Aspects. Elsevier. pp. 519–520. ISBN 978-1-4832-6370-0.

- ^ a b N.S (April 2003). "Biomedicine: Shots stop allergic reactions to venom". Science News. 163 (16): 252. doi:10.1002/scin.5591631613. JSTOR 4014421.

- ^ Torsney, P.J. (November 1973). "Treatment failure: insect desensitization. Case reports of fatalities". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 52 (5): 303–6. doi:10.1016/0091-6749(73)90049-3. PMID 4746792.

- ^ Golden, David B. K. (27 November 1981). "Treatment Failures With Whole-Body Extract Therapy of Insect Sting Allergy". JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 246 (21): 2460–3. doi:10.1001/jama.1981.03320210026018. PMID 7299969.

- ^ Clarke, Paul S. (December 1986). "The natural history of sensitivity to jack jumper ants (Hymenoptera formicidae Myrmecia pilosula) in Tasmania". The Medical Journal of Australia. 145 (11–12): 564–6. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.1986.tb139498.x. PMID 3796365.

- ^ Ford, SA; Baldo, BA; Weiner, J; Sutherland, S (March 1991). "Identification of jack-jumper ant (Myrmecia pilosula) venom allergens". Clinical and Experimental Allergy. 21 (2): 167–71. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2222.1991.tb00826.x. PMID 2043985. S2CID 35820286.

- ^ a b c Mullins, Raymond J; Brown, Simon G A (13 November 2014). "Ant venom immunotherapy in Australia: the unmet need" (PDF). The Medical Journal of Australia. 201 (1): 33–34. doi:10.5694/mja13.00035. PMID 24999895. S2CID 23889683.

- ^ a b c Crawley, Jennifer; Mather, Anne (15 October 2014). "Axe looms over jack jumper ant allergy program". The Mercury. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f Kennedy, Shannon (16 March 2011). "Dealing with allergic reaction from jack jumper ant sting". abc.net. ABC News. ABC South West WA. Retrieved 19 August 2014.

- ^ "Stinging ants". Australian Venom Research Unit. University of Melbourne. 5 June 2018. Archived from the original on 11 January 2015.

- ^ Settipane, Guy A.; Boyd, George K. (1 March 1989). "Natural History of Insect Sting Allergy: The Rhode Island Experience". Allergy and Asthma Proceedings. 10 (2): 109–113. doi:10.2500/108854189778961053. PMID 2737467.

- ^ White, Julian (2013). A Clinician's Guide to Australian Venomous Bites and Stings: Incorporating the Updated Antivenom Handbook. Melbourne, Victoria: CSL Ltd. p. 233. ISBN 978-0-646-57998-6.

- ^ Brown, Simon G.A. (August 2004). "Clinical features and severity grading of anaphylaxis". Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 114 (2): 371–376. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2004.04.029. PMID 15316518.

- ^ Moneret-Vautrin, DA; Morisset, M; Flabbee, J; Beaudouin, E; Kanny, G (April 2005). "Epidemiology of life-threatening and lethal anaphylaxis: a review" (PDF). Allergy. 60 (4): 443–51. doi:10.1111/j.1398-9995.2005.00785.x. PMID 15727574. S2CID 1258492. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 February 2015. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- ^ a b "Invasive Ant Threat – Myrmecia pilosula (Smith)" (PDF). Land Care Research New Zealand. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 February 2013. Retrieved 24 August 2014.

- ^ Bradley, Clare (2008). "Venomous bites and stings in Australia to 2005". Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Government of Australia. p. 57. Retrieved 27 November 2014.

- ^ "2006 Census QuickStats (Tasmania)". 2006 Census QuickStats. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 27 November 2014.

- ^ a b Davies, Noel W; Wiese, Michael D; Brown, Simon GA (February 2004). "Characterisation of major peptides in 'jack jumper' ant venom by mass spectrometry" (PDF). Toxicon. 43 (2): 173–183. Bibcode:2004Txcn...43..173D. doi:10.1016/j.toxicon.2003.11.021. PMID 15019477.

- ^ a b Brown, Simon G. A.; van Eeden, Pauline; Wiese, Michael D.; Mullins, Raymond J.; Solley, Graham O.; Puy, Robert; Taylor, Robert W.; Heddle, Robert J. (April 2011). "Causes of ant sting anaphylaxis in Australia: the Australian Ant Venom Allergy Study". The Medical Journal of Australia. 195 (2): 69–73. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2011.tb03209.x. hdl:1885/31841. PMID 21770873. S2CID 20021826.

- ^ "Most Dangerous Ant". Guinness World Records. Retrieved 27 August 2014.

- ^ Harris, R. "Invasive ant pest risk assessment project: Preliminary risk assessment" (PDF). Invasive Species Specialist Group. p. 13. Retrieved 13 September 2014.

- ^ "Snakebite & Spiderbite Clinical Management Guidelines 2007 – NSW" (PDF). Department of Health, NSW. 17 May 2007. p. 58. Retrieved 10 November 2013.

- ^ Donovan, Gregory R.; Street, Michael D.; Baldo, Brian A. (1995). "Separation of jumper ant (Myrmecia pilosula) venom allergens: A novel group of highly basic proteins". Electrophoresis. 16 (1): 804–810. doi:10.1002/elps.11501601132. PMID 7588566. S2CID 45928337.

- ^ Billen, Johan (January 1990). "The sting bulb gland in Myrmecia and Nothomyrmecia (Hymenoptera : Formicidae): A new exocrine gland in ants" (PDF). International Journal of Insect Morphology and Embryology. 19 (2): 133–139. doi:10.1016/0020-7322(90)90023-I.

- ^ Matuszek, M. A.; Hodgson, W.C.; Sutherland, S.K.; King, R.G. (1992). "Pharmacological studies of jumper ant (Myrmecia pilosula) venom: evidence for the presence of histamine, and haemolytic and eicosanoid-releasing factors". Toxicon. 30 (9): 1081–1091. Bibcode:1992Txcn...30.1081M. doi:10.1016/0041-0101(92)90053-8. PMID 1440645.

- ^ a b Wiese, M. D.; Brown, S. G. A.; Chataway, T. K.; Davies, N. W.; Milne, R. W.; Aulfrey, S. J.; Heddle, R. J. (12 March 2007). "Myrmecia pilosula (Jack Jumper) ant venom: identification of allergens and revised nomenclature". Allergy. 62 (4): 437–443. doi:10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01320.x. PMID 17362256. S2CID 21885460.

- ^ Wanandy, Troy; Gueven, Nuri; Davies, Noel W.; Brown, Simon G.A.; Wiese, Michael D. (February 2015). "Pilosulins: A review of the structure and mode of action of venom peptides from an Australian ant Myrmecia pilosula". Toxicon. 98: 54–61. Bibcode:2015Txcn...98...54W. doi:10.1016/j.toxicon.2015.02.013. PMID 25725257.

- ^ Inagaki, Hidetoshi; Akagi, Masaaki; Imai, Hirotami T.; Taylor, Robert W.; Wiese, Michael D.; Davies, Noel W.; Kubo, Tai (September 2008). "Pilosulin 5, a novel histamine-releasing peptide of the Australian ant, Myrmecia pilosula (Jack Jumper Ant)". Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 477 (2): 411–416. doi:10.1016/j.abb.2008.05.014. PMID 18544336.

- ^ Hayes, A. Wallace (2007). Principles and Methods of Toxicology (Fifth ed.). CRC Press. p. 1026. ISBN 978-0-8493-3778-9.

- ^ Wiese, Michael D.; Chataway, Tim K.; Davies, Noel W.; Milne, Robert W.; Brown, Simon G.A.; Gai, Wei-Ping; Heddle, Robert J. (February 2006). "Proteomic analysis of Myrmecia pilosula (jack jumper) ant venom". Toxicon. 47 (2): 208–217. Bibcode:2006Txcn...47..208W. doi:10.1016/j.toxicon.2005.10.018. PMID 16376960.

- ^ a b Wu, Qi-xuan; King, M.A.; Donovan, G.R.; Alewood, D; Alewood, P; Sawyer, W.H.; Baldo, B.A. (September 1998). "Cytotoxicity of pilosulin 1, a peptide from the venom of the jumper ant Myrmecia pilosula". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - General Subjects. 1425 (1): 74–80. doi:10.1016/S0304-4165(98)00052-X. PMID 9813247.

- ^ King, MA; Wu, QX; Donovan, GR; Baldo, BA (1 August 1998). "Flow cytometric analysis of cell killing by the jumper ant venom peptide pilosulin 1". Cytometry. 32 (4): 268–73. doi:10.1002/(sici)1097-0320(19980801)32:4<268::aid-cyto2>3.0.co;2-e. PMID 9701394.

- ^ Upadhyay, Ravi Kant; Ahmad, Shoeb (2010). "Allergic and toxic responses of insect venom and its immunotherapy". Journal of Pharmacy Research. 3 (12): 3123–3128. ISSN 0974-6943.

- ^ Beckage, Nancy; Drezen, Jean-Michel (2011). Parasitoid Viruses: Symbionts and Pathogens (1st ed.). Academic Press. p. 238. ISBN 978-0-12-384858-1.

- ^ a b Hoffman, Donald (2010). "Ant venoms" (PDF). Current Opinion in Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 10 (4): 342–346. doi:10.1097/aci.0b013e328339f325. PMID 20445444. S2CID 4999650.

- ^ Street, M. D.; Donovan, G. R.; Baldo, B. A.; Sutherland, S. (June 1994). "Immediate allergic reactions to Myrmecia ant stings: immunochemical analysis of Myrmecia venoms". Clinical & Experimental Allergy. 24 (6): 590–597. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2222.1994.tb00957.x. PMID 7922779. S2CID 21012644.

- ^ a b c Costigan, Justine. "Jumping jack flash". Royal College of Pathologists of Australasia. Retrieved 22 August 2014.

- ^ "Insect bites and stings". Healthdirect Australia. Department of Health. Retrieved 24 August 2014.

- ^ Severe Allergic Reaction (Anaphylaxis) for Complementary Health Care Practitioners (PDF). Government of New South Wales. 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 June 2014. Retrieved 24 August 2014.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Ring, Johannes (2010). Anaphylaxis (Chemical Immunology and Allergy). S. Karger Publishing. p. 144. ISBN 978-3-8055-9441-7.

- ^ Lockey, Richard; Ledford, Dennis (2014). Allergens and Allergen Immunotherapy: Subcutaneous, Sublingual, and Oral (Fifth ed.). CRC Press. p. 410. ISBN 978-1-84214-573-9.

- ^ a b "Clinical Toxicology Resources". University of Adelaide. Retrieved 24 February 2015.

- ^ "Allergy and Anaphylaxis Question and Answer" (PDF). South Eastern Area Laboratory Services. Government of New South Wales. Retrieved 22 August 2014.

- ^ Hodgson, Wayne C. (January 1997). "Pharmacological action of Australian animal venoms". Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology and Physiology. 24 (1): 10–17. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1681.1997.tb01776.x. PMID 9043799. S2CID 19703351.

- ^ Del Toro, Israel; Ribbons, Relena R.; Pelini, Shannon L. (August 2012). "The little things that run the world revisited: a review of anti-mediated ecosystem services and disservices (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)" (PDF). Myrmecological News. 17: 143–146. ISSN 1997-3500. Retrieved 2 September 2014.

- ^ Magill, Alan; Ryan, Edward T.; Maguire, James H.; Hill, David R.; Soloman, Tom; Strickland, Thomas (2012). Hunter's Tropical Medicine and Emerging Infectious Disease: Expert Consult – Online and Print (9th ed.). Saunders. p. 970. ISBN 978-1-4160-4390-4.

- ^ Diaz, James H. (September 2009). "Recognition, Management, and Prevention of Hymenopteran Stings and Allergic Reactions in Travelers". Journal of Travel Medicine. 16 (5): 357–364. doi:10.1111/j.1708-8305.2009.00316.x. PMID 19796109.

- ^ a b Donovan, GR; Street, MD; Tetaz, T; Smith, AI; Alewood, D; Alewood, P; Sutherland, SK; Baldo, BA (August 1996). "Expression of jumper ant (Myrmecia pilosula) venom allergens: post-translational processing of allergen gene products". Biochemistry and Molecular Biology International. 39 (5): 877–85. doi:10.1080/15216549600201022. PMID 8866004. S2CID 24099626.

- ^ Douglas, RG; Weiner, JM; Abramson, MJ; O'Hehir, RE (1998). "Prevalence of severe ant-venom allergy in southeastern Australia". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 101 (1 Pt 1): 129–131. doi:10.1016/S0091-6749(98)70206-4. PMID 9449514.

- ^ Hammond, Jane (18 July 2011). "Native ants are deadly threat". The West Australian. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ^ a b c d "Position Statement: Jack Jumper Ant Venom Immunotherapy" (PDF). Australasian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy (ASCIA). Retrieved 21 August 2014.

- ^ Mayse, Mark A. (1981). "Bites and stings". Science. 214 (4520): 494. Bibcode:1981Sci...214..494M. doi:10.1126/science.214.4520.494-a. PMID 17838383. S2CID 31993424.

- ^ "Jack Jumper Ant Allergy". Australasian Society of Clinical and Immunology and Allergy (ASCIA). January 2010. Retrieved 14 February 2015.

- ^ "Newsletter of Manly Council's Bushland Reserves Summer 2003 — Manly's Bushland News 3" (PDF). Manly Council. Government of New South Wales. 2003. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- ^ Wiese, Michael (2008). Characterisation of Jack Jumper Ant Venom: Definition of the Allergic Components and Pharmaceutical Development of Myrmecia pilosula (Jack Jumper) Ant Venom for Immunotherapy. VDM Verlag. ISBN 978-3-639-05169-8.

- ^ Wiese, Michael D.; Milne, Robert W.; Davies, Noel W.; Chataway, Tim K.; Brown, Simon G.A.; Heddle, Robert J. (January 2008). "Myrmecia pilosula (Jack Jumper) ant venom: Validation of a procedure to standardise an allergy vaccine". Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis. 46 (1): 58–65. doi:10.1016/j.jpba.2007.08.028. PMID 17933477.

- ^ Thistleton, John (6 July 2014). "Government urged to fund anti-venom treatment for jack jumper ant stings". The Canberra Times. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- ^ Mather, Anne (26 July 2014). "More bite for research into jack jumpers". The Mercury. Retrieved 5 December 2014.

- ^ Crawley, Jennifer (25 October 2014). "If jack jumper program is axed someone will die, Dad warns". news.com.au. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ^ Gardiner, Melanie (4 November 2013). "Ferntree Gully mum Michelle Madden continues online petition for jack jumper ant therapy for son Ryan". The Herald Sun. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ^ a b Brown, Simon G.; Heddle, Robert J. (December 2003). "Prevention of anaphylaxis with ant venom immunotherapy". Current Opinion in Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 3 (6): 511–6. doi:10.1097/00130832-200312000-00014. PMID 14612677. S2CID 21116258.

- ^ "Are rapid dose increases during venom immunotherapy safe?". American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology. 29 March 2012. Archived from the original on 13 September 2014. Retrieved 13 September 2014.

- ^ Brown, Simon G.A.; Wiese, Michael D.; van Eeden, Pauline; Stone, Shelley F.; Chuter, Christine L.; Gunner, Jareth; Wanandy, Troy; Phillips, Michael; Heddle, Robert J. (July 2012). "Ultrarush versus semirush initiation of insect venom immunotherapy: A randomized controlled trial". Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 130 (1): 162–168. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2012.02.022. PMID 22460067.

- ^ Coulter, Ellen (4 December 2014). "Jack jumper ant allergy research looks at why desensitisation programs only work for some". ABC News. Retrieved 5 December 2014.

Cited texts

[edit]- Hölldobler, Bert; Wilson, Edward O. (1990). The Ants. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-04075-5.

- Smith, Frederick (1858). Catalogue of hymenopterous insects in the collection of the British Museum part VI (PDF). London: British Museum.

External links

[edit] Media related to Myrmecia pilosula at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Myrmecia pilosula at Wikimedia Commons- Jack jumper ant in the Catalogue of Life

- Jack jumper ant in the Universal Protein Resource

- Video about the Jack jumper ant — YouTube

- JJA Desensitisation Program website

- Alex Wild (15 January 2009). "Which ants should we target for genome sequencing?". Myrmecos.