Estates General of 1576

The Estates General of 1576 was a national meeting of the three orders of France; the clergy (First Estate), nobility (Second Estate) and common people (Third Estate). It was called as one of the many concessions made by the crown to the Protestant/moderate Catholic rebels to bring the Fifth War of Religion to a close. The generous terms of the peace made with the rebels provoked a strong backlash from militant Catholics who established the first Catholic Ligue (League) in opposition to the terms. Henri at first sought to suppress the ligue before attempting to co-opt it. Both king Henri III and the ligue looked to the upcoming Estates General to secure advantage. For the first time in the history of the Estates General, a fierce election campaign would follow between Protestant, royalist and ligueur candidates, in the end very few Protestants would be represented in the Estates.

The Estates opened on 6 December, and in the first few days, Henri was confronted by a coalition of the First and Second Estate that attempted a constitutional revolution which would have seen the unanimous decision of the Estates take on a legislative power he could not overrule. He declined to endorse this proposal and the Estates did not feel able to push it. Matters then turned to the unity of religion, with all three Estates declaring their support for the re-establishment of religious unity in France. However, the Second Estate had several objectors, and the Third Estate was riven with divisions between the pro and anti-war factions with only a narrow majority for a war against heresy in December. By January as the problems of the royal finances became apparent, and the Protestants in the south of France began seizing towns in response to the Estates General, anti-war attitudes continued to grow until by mid January the Third Estate no longer supported the use of force to establish religious unity. Meanwhile, embassies were sent out to the chief Protestant princes to ensure any conflict was handled properly. Henri, keen to seize on the earlier calls of the Estates for war looked to the Estates to provide him financial assistance to do so. He was able to coax the First Estate to provide him 450,000 livres, but the Second Estate refused to provide any money as did the Third, which also shot down alternate tax proposals. Frustrated Henri attempted to alienate the royal domain to support a war effort, and while the First and Second Estate approved of this, Jean Bodin ensured the Third Estate did not allow it. By the end of February the Estates wrapped up with Henri resigning himself to the fact he could not prosecute a war without funds. Yet the conflict had already begun in the provinces and as such a brief campaign would be required to hopefully overturn the humiliation of the Fifth War of Religion.

The new war would last until September, and be brought to an end with a minor royal victory in the Edict of Poitiers which provoked far less opposition than the earlier Edict of Beaulieu, its terms being significantly more moderate. The cahiers (books of grievances compiled by the Estates) would go on to form the basis for the landmark Great Ordinance of Blois which was published in 1579. This Ordinance altered royal justice, eligibility for church careers, the rules of finance, the structure and funding of the army and royal household, the laws as concerned royal governors and more over 363 articles. It would remain an important part of French law until the end of the ancien régime.

Unsatisfactory peace

[edit]Peace of Monsieur

[edit]

By early 1576 the fifth war of religion had decidedly turned against the crown. the Protestant king of Navarre was established in Saumur from where he dominated Anjou, Guyenne, Poitou and Béarn; the duc d'Alençon (rebellious brother of the king) controlled much of Berry, the Bourbonnais and the Nivernais; the seigneur de Coligny (son of the late Protestant Admiral) held Dauphiné; the politique baron de Damville, brother of the duc de Montmorency controlled Languedoc, Provence and Auvergne; finally the prince de Condé menaced Picardie.[1] The rebel forces totalled around 30,000 men which was a far greater number than king Henri III had capacity to muster against them.[2]

Henri lacked money for troops (those he had were predominately mercenary in composition) and had only limited territory under his control (largely confined to the Île de France, Bourgogne and Champagne). Only support from España had the potential to salvage the royal war effort.[3]

Faced with an unfavourable war situation, Henri decided to seek peace with the Protestant and their allied politique (Catholics who felt persecution was counter-productive) forces. On 5 May 1576 Henri established the Edict of Beaulieu, known to history as the peace of Monsieur (Monsieur being the honorary name given to the king's brother the duc d'Alençon. The name of the peace reflect the commonly held assumption that it had been Alençon's participation alongside the rebels that forced Henri to the table.[4] The treaty would largely be the work of his mother (Catherine), who was keen to see her two eldest surviving sons reconciled.[5]

Generous terms

[edit]The peace was the most generous of the civil war peaces to the Protestants. Across the country the free practice of Protestantism was permitted. This was with the exception of the area surrounding Paris (within four leagues) and that about the court wherever it might be (two leagues).[3] The Protestants were allowed to build churches and hold synods. Cross-confessional chambers were to be established in each Parlement of France with equal numbers of Protestant and Catholic judges. These were to hear any case about violations of the terms of the peace, or cases which involved plaintiffs of both faiths.[6] Eight places de sûreté (fortified towns the Protestants could hold as security for the execution of the terms of the peace) were granted.[4] These were Aigues-Mortes, Beaucaire, Périgueux, Le Mas de Verdun, La Rochelle, Issoire, Nyons and Serres.[7]

For the noble backers of the Protestant cause there were also great benefits, the baron de Damville was formally reinstated in his charge as governor of Languedoc (which he had never been extricated from despite being deposed during the civil war). The prince de Condé was re-established as the governor of Picardie.[8][9] At first Condé demanded Boulogne as a city for himself in his restored governate. This was unacceptable, and thus Amiens was proposed a counter-offer before Condé settled at last on Péronne which Henri agreed to (despite preferring to cede Saint-Quentin to the prince).[10] Alençon was made duc d'Anjou, Berry and Touraine, substantially increasingly his appanage. He also received the cities of La Charité and Saumur as a compromise after the Protestants demanded them be added to the places de sûreté.[11][4] In total the lands he received were worth around 300,000 livres in annual incomes.[5] The king of Navarre secured the addition of Poitou and the Angoumois into his expansive governate of Guyenne and payment of his extensive debts (600,000 livres). Navarre further demanded for his part a pension of 40,000 livres and French assistance in the reconquest of his kingdom, which had largely fallen to the Spanish in 1515.[12]

The Catholic politiques who had backed the Protestant cause were promised by the king that within six months of the peace they would receive an Estates General at which the administration of the kingdom could be reconfigured to their desires.[13] It was also hoped that the Estates would bring back order to the kingdom after the chaos of the civil wars. This Estates General was to take place at Blois.[5] The convoking of an Estates General had been a topic both Alençon (in his Dreux manifesto) and the Protestants had expounded upon the importance of for several years.[14] The wording of the treaty itself was actually somewhat ambiguous on this point. Henri committed according to the terms to 'listen to the remonstrances of his subjects' so that the kingdom might enjoy tranquillity. Le Roux therefore argues, it was a royal decision for this to take the form of an Estates General.[15] Heller argues, that even had it not been a component of the Edict of Beaulieu, the ruinous state of royal finances would have necessitated it be called regardless.[16] In total the crowns debts were around 100,000,000 livres by 1576 and the royal creditors were beginning to get restless.[17][18]

Reaction

[edit]

Henri was humiliated by the peace, with the consequence for violating his authority being reward, his treasury empty, and his brother enriched at the head of an alliance of Protestants and politique Catholics. Henri disgraced the bishop of Limoges for his role in negotiating the terms.[19] For two months he refused to meet with his mother Catherine who had been the architect of the peace as a whole.[20] The peace was however undertaken cynically, Catherine who was its prime architect boasted to Nevers in early 1577 that neither she nor Henri cared to see it enforced, and that the goal of the generous terms was to win over Alençon from the rebel cause.[14][21] Once the level of opposition became apparent to Henri he no longer resigned himself to acceding to the terms.[22]

As regards Henri's attitude to the peace, he wrote to Damville on 21 December to let it be known that it was his intention to restore religious unity in the kingdom, meanwhile to the governor of Péronne on 22 December he announced that it would be necessary to tolerate the presence of multiple faiths in France. His message adapted to the target of his discussion.[23]

Upon presenting the edict of Beaulieu to the Parlement of Paris, Henri had to force through its registration. For this the personal presence of both Henri and the princes du sang (princes of the blood - those princes descended from the royal family through the male line) was required.[24][25] When he attempted to hear a Te Deum in celebration of the peace at the Notre Dame his entry was blocked by the clergy and people of Paris, much to his frustration.[26]

There was much opposition to the peace for the components which allowed those who had pillaged and ruined France in the last years to go without punishment.[27]

First Catholic ligue

[edit]This peace was also unacceptable to many Catholics. In opposition to its execution some formed defensive Catholic Ligues (Leagues). In Paris the perfumer La Bruyère played an important role in the cities ligueur (leaguer) movement, passing around membership lists in an attempt to drive recruitment. The traditional Te Deum, fireworks, and bonfire to celebrate the recently established Edict of Beaulieu was poorly received in the city, with many boycotting the event.[28][6] According to De Thou it was only the active suppression undertaken by his father in the Paris Parlement that stopped the Parisian ligue from growing.[29]

Most famously, in Péronne (Picardie), the governor Jacques d'Humières became the figurehead for a ligue of local Catholic notables (around 150 in number, led by Jacques d'Happlaincourt and Michel d'Estourmel, both clients of the Lorraine family) determined not to allow the Protestant prince de Condé to establish a Protestant garrison in his city.[29] Picardie, and Péronne were of particular importance, as they controlled the border with Spanish Nederland, providing them significant strategic value.[26] Covert meetings in support of the ligue established a council to 'protect Catholicism'. Hand in hand with 'protecting Catholicism' was a desire to see Protestantism extirpated.[9] Henri responded to Humières with tacit encouragement.[30] The movement quickly spread, both to other towns and cities in Picardie such as Amiens, Saint-Quentin, Corbie, Abbeville and Beauvais. It then spread across France more broadly, seeing particular interest from the duc de Thouars in his governate of Poitou. Thouars brought around him 60 gentleman for the establishment of his ligue.[31][29] There were also disorders in favour of the ligue to be found in Bretagne, and Rouen.[31] In September Henri ordered that the ligues disband.[32] Henri suspected that such a movement must be the doing of the great Catholic princes, the duc de Guise, Mayenne and Nemours and on 2 August had them swear to uphold the Edict of Beaulieu.[32] The historian of the ligue Constant has found no evidence of their involvement. This is not a universal opinion, other historians such as Konnert see Guise as involved in the establishment of this first Catholic ligue.[8][9] Jouanna argues that the influence of Guise was indirect, and he was the object of desire of the ligue, i.e. who they wished to assume leadership of their movement.[31]

Guise took the opportunity of the founding of this Catholic ligue to publish a manifesto to all of France in favour of it in which he emphasised the need to "establish the whole law of God, to restore and retain the holy service of this law according to the form and manner of the Holy Catholic, Apostolic and Roman Church".[9] Guise urged the people of France to preserve Henri in the proper splendour and authority which he was due as king of France but not to act in a way that might be contrary to the decisions that are established by the upcoming Estates General.[33] For historians such as Thompson, the true purpose of the Catholic ligue once it was co-opted by great nobles such as Guise was to bring back the power of a feudal nobility to France.[34]

Regardless, their involvement in the establishment, whatever its degree was significantly more discreet than during the period of the second Catholic ligue in 1584. With an Estates General coming soon, Guise looked to evaluate the support that could be expected for the movement.[35]

Conscious that this ligue represented a great threat to his authority Henri hoped to use the Estates General as a venue by which to combat its intrusions on his royal prerogatives.[36] While it had not been his idea therefore to see the bodies convocation, he recognised that there was considerable opportunity for him in their meeting.[37]

On 6 August he promulgated the convocation of the Estates. The elections would be undertaken throughout October.[15] It was intended at first that the Estates would begin on 15 November.[38]

Election of the delegates

[edit]The elections to the Estates were hotly contested between extreme Catholics and moderate Catholics/Protestants.[39] This was a first for the body, which traditionally did not take the form of an electoral campaign to see as many favourable delegates as possible.[32]

This was not the case across all of France, in Blois, the Protestants protested the failures for the recent treaty to be adhered to, while the large politique Catholic population of the baillage emphasised matters other than religion. In the Nivernais the ligueur movement was largely absent.[39]

Second Estate elections

[edit]In Poitiers, Péronne, the Pays de Caux, Vitry and Provins there were disorders associated with the elections.[39]

In Provins the Protestant nobles of the city demanded the bailli (bailliff) swear to uphold the Edict of Beaulieu, the bailli, supported by radical Catholic nobles (including the governor of the province, Guise) rejected this notion. The Protestant nobles therefore brought around 20 armed men to bear in the city.[39] This group of armed nobles were chased away by a larger number of armed Catholics. Disputes continued for the process of writing the cahiers (cahiers de doléances - books of grievances that the deputies wished to be addressed at the Estates General).[40] The Protestants present threatened the Catholics who responded by darkly suggesting they would kill the Protestants, denouncing Protestantism as a religion which instructed its followers in war, murder, sedition and assassination. Tempers were lowered, and the next day the compromise was found that the cahiers would insist on there being only one religion in France, but not to specify in the wording which religion was meant, so that the Catholics might interpret it as Catholicism and the Protestants as Protestantism. While the Catholic deputies refused to recognise the Edict of Beaulieu in the cahiers they did not stop the Protestants writing in support of it in the cahiers.[41]

The conflict over the election in Provins was complicated by a distinct conflict between the noblesse de race (ancient military nobility) and their enemies in the newer nobility (who had purchased their way into the order). The new nobles were expelled from the meeting.[42]

In Poitiers, the duc de Thouars skilfully directed the assembly towards a Catholic candidate without the Protestants present realising until it was too late.[41]

In Vitry-le-François, the favourite of the duc d'Alençon the seigneur de Bussy was pitted against the ultra-Catholic vicomte de Lignon. In the end the royalist Jacques d'Anglure was able to best Lignon by 31 votes to 18.[41]

In Péronne the ligueur Humières had moved the process of selection to Montdidier to better keep the proceedings orderly. Thirty-seven nobles were present, of whom seven were Protestant. The ligueurs of the area had already prepared cahiers for adoption, and these were accepted with little difficulty. The Protestants present had one success however, in that they got a modification of the terms that demanded their expulsion from the kingdom to instead allow them to practice in the privacy of their homes.[41]

In nearby Saint-Quentin it was argued by the cahiers that foreigners should be excluded from France except for at the specific request of the Estates General.[43]

Across upper Normandie and Picardie the ligue did well, Antoine de Bigars was elected for Rouen, he would go on to be a key ligueur captain during the 1580s, the sieur de Maineville was also elected for the baillage of Gisors.[44] He would be present for the founding of the second Catholic ligue in 1584.[45] During the coming Estates general he got into trouble with Henri for his demand that the Protestant princes du sang (princes of the blood) be stripped of their right to succeed to the French throne. This would have had personal advantage to him, he was governor for the comte de Soissons one of the Catholic Bourbon princes du sang.[46]

In the baillage of Senlis, the Protestant Du Plessis Mornay was elected (supported by both Protestant and Catholic voters) but he refused however to take his place in the Estates.[47][39] Instead of attending, Du Plessis Mornay issued an anonymous remonstrance to the upcoming Estates titled 'Remonstrance d'un bon Catholique François aux trois estats de France' (remonstrance of a good Catholic Frenchman to the three estates of France). In this work he protested against the naturalisation of foreign citizens as French and the influence of Italians over the French church and economy. He urged Henri make the economy more protectionist, intervening in favour of French manufacturing. Beyond economic matters he turned to the religious question, arguing all Protestants had Catholic friends and all Catholics Protestant ones, no matter how many times brothers fight on the battlefield they will never defeat one another.[48] Du Plessis Mornay concluded by warning that 'Machiavellians' were trying to perpetuate civil wars in the kingdom.[49]

In the baillage of Chaumont, the local nobility complained in their cahiers that they had suffered as a result of the marauding both of domestic military forces and mercenaries introduced into the country.[50]

The nobility of the baillage of Nevers selected as their representative Pierre de Blanchefort who would take an active role in the affairs of the Estates General. In the cahiers for his baillage there was an impassioned plea for provincial autonomy from the whims of the king. It was proposed that bailli and sénéchaux (bailliffs and seneschals) be elected every three years by the Estates of the local baillage. By this means the provincial nobility were to exist outside the whims of the king and great nobles as to the allocation of offices. It was further argued that the king should not interfere with the laws and customs of a province without going through the local Estates. This would not only have furthered provincial autonomy, but would also make the Estates General largely redundant.[51]

Third estate elections

[edit]Chalon

[edit]In Chalon-sur-Saône there was an active Protestant community. Their politique allies were able to dominate the choosing of representatives, selecting the mayor and an officer of the baillage. When it came time to draw up the Estates cahiers a more Catholic party appeared and challenged the pervading push for a religious tolerant cahiers.[41]

Lyon

[edit]In Lyon the ligueur party was ascendant, and wrote up cahiers in which they demanded that Protestantism be outlawed - including the suppression of freedom of conscience - further they insisted the Tridentine Decrees be adopted in France.[41] Alongside these religious objections there was also frustration at the presence of Italians in the kingdom, who, according to the cahiers did not come to the kingdom to further the interests of the state, but rather for their own profit, using 'subtle devices' (meaning financial devices) in which their people excel'.[52]

The cahiers were the work of Claude de Rubys and were divided into three sections, firstly religion, then politics and finally the policy of the kingdom. Rubys' influence was more strongly felt in shaping the first two thirds while the final third was more a reflection of the grievances of the Lyon merchant class. In this third section the restoration of free trade was demanded, arguing that its absence was making the city less competitive against other finance centres.[53][54] It was largely a protectionist set of grievances.[55]

Champagne

[edit]In the baillages of both Chartres and Troyes a minority of the cahiers assembled were in favour of the ligueur program.[41] Within the city of Troyes itself, the mayor Pierre Belin ensured that no Protestants were elected to represent the city. Two of the representatives, Belin himself and the lieutenant-general Philippe Belin were therefore ardent ligueurs.[56] They promoted the ligue strongly in Troyes.[57] Their cahiers also contained anti-Italian views, expressing concern at the growing number of offices held by Italians.[43]

Rouen

[edit]In the cahiers for the city of Rouen, the grievances of the populace appeared generally fairly moderate. There were calls to see the Catholic clergy improved in their standards, create new schools, restore the much declined university of Caen, and have a firmer hand in dealing with piracy. There was much aggrievement however as concerns venal offices in the city, which were proliferating much to the displeasure of many. Rouen called for the end of venal office and the reduction of the quantity of legal offices overall.[58]

Paris

[edit]The cahiers of Paris were drawn up by a lawyer named Pierre le Tourneur, better known as Versoris. The cahiers he drew up contained objections towards the behaviour of both the First and Second Estates, concerns about how justice was administered and financial abuses by the Italians. The reason for the heavy taxes under which they suffered was alleged to by those Italian financiers. Frenchman had been excluded from the privilege of conducting the tax farms according to the cahiers.[59] It was also demanded that the king restore unity of religion in the kingdom.[60]

Summary

[edit]The cahiers of the Estates were in agreement only in their deploring of the depredations of the soldiery, opposition to the crown's fiscal measures and the wasteful manner in which public funds were disposed of.[41] The role of the 'Italian financier' came in for particular scrutiny by all three Estates.[61]

Those of the Third Estate tended to focus on the issues of the oppression of feudal levies, violence inflicted upon them by the Second Estate, the crimes of the soldiery, overwhelming royal taxation, venal office and slow justice. Criticism was also levelled at 'greedy foreigners' who were running the kingdom. By this was meant Catherine and her Italian entourage.[15] A minority of cahiers demanded the establishment of religious uniformity, but there was general concern for a Catholic reformation. Absentee priests, drunken clerics, simony, poor training were all deplored in various cahiers. It was proposed that by the election of priests and justices by the communities, these problems could be overcome.[62]

The ligue enjoyed strong support among each of the three Estates.[8] From Geneva, the Protestant theologian Théodore de Bèze despaired that the Catholics had won in the election what they failed to win on the battlefield.[42] It was not an entirely ligueur assembly however, and many politique Catholics were represented across the body.[63]

Overall the elections were conducted without significant misconduct, though there were some complaints from Protestants about irregularities.[41] Constant argues that the elections were mostly fair and that the deputies were elected without significant pressures.[64] In some areas, the announcement of the location of elections was allegedly undertaken during mass, which precluded local Protestants from participating. In some others as demonstrated above, Protestants were barred from participation.[65] The Protestants hampered their own successes in some regards by refusing to participate on the grounds that if they did, it would be rigged against them.[66]

It is undeniable that if the Protestants had participated, they could have sent many deputies to the Estates particularly for the south and south-west of France where they held sway. However, there were concerns among some Protestants that their participation would illustrate their numerical inferiority in comparison to their Catholic counterparts. This was particularly true now their political allies the politiques were beginning to defect to the royal party, most notably illustrated with Alençon/Anjou.[67] Therefore, no delegations came to the Estates from either La Rochelle or many of the bailliages and sénéchaussée of the Midi.[68]

In protest of this, both Condé and Navarre rejected the call of the Estates.[69] Navarre added to this a pre-emptive protest of whatever decisions they might reach, thereby undermining its legitimacy.[70]

In one case the ligue successfully replaced the royalist Second Estate delegate for the pays de Caux on a technicality.[32] Henri was not above intervening to ensure certain elections went his way either. On 15 November he ordered the replacement of the deputy that had been selected by the Third Estate of Rouen, Emery Bigot.[71] This was just one of several elections in which he personally intervened.[32]

Court politics

[edit]Anjou

[edit]Catherine worked on her son the duc d'Anjou (formerly Alençon), and was able to convince him to break with his former allies and arrange a reconciliation between him and his brother Henri. Alongside the skill of Catherine as a coalition breaker, Anjou tired of Protestant allies and his favourites feared being absorbed into the Protestant armies (his chief favourite the seigneur de Bussy despised the Protestants).[67] Anjou was further developing ambitions to establish himself in Nederland, and the support of his brother in this enterprise would be important.[21] He had just received an appeal from the Catholic provinces of Nederland to this effect. Regardless of his brothers support this would necessitate a break with his Protestant backers.[72] Alongside these more material reasons to reconcile with the king, he had also been seduced by Charlotte de Sauve, a favourite of Catherine's.[67] On 7 November Anjou met his brother at Ollainville and embraced, the two even sharing a bed as a sign of their closeness.[73] Henri also received with a smile Anjou's favourite, the seigneur de Bussy and his chancellor Renaud de Beaune as a demonstration of his sincerity.[72]

The closeness was however an illusion, Anjou was fully aware of the strength of his position, particularly at Blois which was so close to his greatly expanded appanage. Within days tensions re-emerged between the brothers, many men drawing up their wills before coming to court due to the atmosphere of hostility.[74] It was nevertheless important that the royal family appeared united before the Estates began.[75]

However false their reconciliation may have been, it dispirited the princes former politique allies.[76]

New leader of the ligue

[edit]During November, Henri's government was leant a considerable sum of money (100,000 livres) by the duc de Nevers on the understanding that he would shortly be leading a new war against Protestantism. In the contract that provided the money, Nevers specified that it would be used to 'chase the enemies out of the kingdom'.[77]

Henri resolved that the only way to combat the ever growing ligueur movement was to co-opt it, he therefore assumed leadership of the Catholic ligue on 2 December.[8][78][79] All the provincial and local ligues were thus formally abolished, subordinate to this new national ligue.[30] To this end he wrote to the provincial governors, both to get them to encourage their support for the new royal ligue but also to have them modify the ligueur oaths which had been established previously in favour of one that acknowledged royal authority. The new oath stressed obedience to the crown, the suppression of heresy, and the need to bring to pass any order made by the king.[15][36] The oath stated that the members would use their 'property and lives' in service of the commands and orders of Henri after the direction of the state was established by the upcoming Estates General.[80]

Governors, such as the duc de Thouars swore oaths to this ligue.[47] Péronne signed up to the new royal ligue on 13 February, Montdidier two days later, Amiens refused the new royal ligue. When Humières attempted to enter the city, he was rebuffed[15][81] The premier président of the Paris Parlement signed the king's ligue formula on 1 February but modified the oath, with the remainders of the judges signing up to this modified version. In Chalon the new royal ligue was rejected on the grounds that subjects should never be allowed to form a ligue which might interfere with royal authority over them.[82] Across Champagne the lieutenant-general the seigneur de Barbezieux found very little interest in the ligue as he tried to see to its adoption by the various towns and cities. Konnert concludes that across Champagne and more broadly across France the attempted national ligue was dead on arrival.[83] He states however, that given membership of the royal ligue was vigorously pursued by the duc de Guise, that we cannot see in this reluctance a challenge to Henri's having assumed the ligues leadership.[84] Konnert sees the failure of the ligue as reflecting rather the caution of urban communities when confronted with this novelty, the emphasis in the oath on the nobility alienating the urban bourgeois and the lack of a need to have a ligue given there was already a Catholic king and a Catholic heir.[85]

By the means of putting himself at the head of the ligue, Henri hoped to seize the initiative that had been lost to him with the Edict of Beaulieu.[86]

The royal ligue held a different attitude towards Protestantism to the one originally designed. As long as Protestants abided by the decisions undertaken in the coming Estates General, the ligue was to ensure that they enjoyed freedom of conscience and their lives and property were not interfered with.[66] Indeed, there was nothing about the extirpation of Protestantism to be found in the royal ligue. Many Picard and Norman ligueurs therefore covertly altered the wording of the new royal ligue to remove elements that protected Protestantism. An example of this can be seen in the oath overseen by one of the lieutenant-generals of Normandie the seigneur de La Meilleraye with the inhabitants of his government.[87]

Henri even envisaged that he could transform this new ligue under his authority into a method by which to raise militias which could replace the need to have a regular military. He estimated that if each province provided 3000 foot and 800 horse he could build an army of 36,000 men and 6,000 horse. This ambition received a cool reception from the duc de Nevers who argued nobles would not be keen to accept this new duty which lacked a concrete end date, preferring their traditional obligations of service.[82]

Estates convene

[edit]Discussions before the opening

[edit]The first deputies arrived at the château de Blois for the coming Estates during November.[37][67] While the meeting would not formally open until 6 December, some began sitting for discussions from 24 November.[69] These discussions were individual to each Estate and it would only be on 6 December that all the Estates were gathered in one place for the first time.[88] On 29 November Henri dispatched two of his councillors, Morvillier and Lansac to treat with the nobility, encouraging them to support his vision in the coming weeks.[89] That same day Blanchefort and other noble deputies were invited to the house of an anonymous prelate, and presented with articles of a ligue to subscribe to, however Blanchefort, of royalist inclinations. refused.[90] The terms shown to the invited deputies proposed an elective monarchy.[91]

Numbers

[edit]In December the Estates began at Blois, in total there were 383 delegates who arrived for the meeting.[75] This has been broken down by the historian Major as 110 delegates for the First Estate (clergy), 86 for the Second Estate (nobility) and 187 delegates for the Third Estate (commons). Of the 187 delegates for the Third, only 171 would have their credentials approved allowing them to participate.[69] Indeed, the Estates themselves attempted to claim the right to inspect the credentials of deputies. While this would remain a matter of dispute, the deputies succeeded in securing salaries for their members.[92]

There was only one Protestant among the entirety of the Second Estate delegates (the Protestants had by and large boycotted the elections), the sieur de Mirambeau and he left shortly into the assembly.[36] Among the Third Estate there were another handful of Protestant deputies.[14]

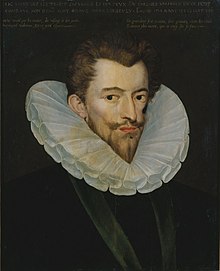

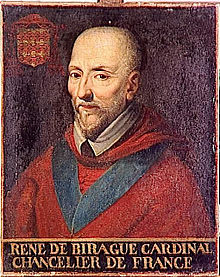

Formal opening

[edit]On 6 December Henri attended mass at the church of Saint-Sauveur. The bishop of Angers, Guillaume Ruzé delivered a sermon on the theme of fearing god, honouring the king and remaining united. This sermon was delivered not only to Henri but to the delegates of the Estates who were with him.[93] Henri then proceeded to the great hall of state in the château de Blois. He was proceeded by two ushers who carried maces. Behind him followed Catherine, his queen Louise, Anjou, Cardinal de Bourbon, the prince du sang duc de Montpensier, Montpensier's son the prince dauphin, the duc de Nevers, duc d'Uzès, the bishop of Laon and Beauvais, other ecclesiastical peers, the chancellor Birague, grand maître de l'artillerie (grand-master of the artillery) Marshal Biron, the members of the conseil privé (privy council) and finally the secretaries of state.[94]

The deputies all rose to greet him, members of the Third keeping their knees partially bent in deference. He made his way to his throne, and then gestured for the deputies to be seated.[94]

With this grand company having arrived. Henri opened the Estates with a speech, deploying his gift for rhetoric to his advantage. The speech was the brainchild of the former garde des sceaux (keeper of the seals). Henri urged the assembled deputies to demonstrate their zeal for both the authority of the king and the restoration of the kingdom. He informed them that they had been brought here to sooth the ills that had entered the kingdom in prior years. He understood the deputies had little insight into the running of state affairs, and blamed him for all that befell them. He countered this by arguing that these troubles had first begun to afflict the kingdom during the minority of Charles IX.[62] They were a consequence, not of his administration, but rather the 'perils of the times'. The nobility came in for a chiding for their decline in virtue, an attempt by Henri to offer an olive branch to the Third Estate.[95] Catherine, the king argued had through her 'love and maternal charity' done much for the kingdom. Henri then reminded the delegates that he had fought in the early civil wars himself, and upon returning to take up the throne in 1574, he had found a kingdom consumed by disorders. This was why he had worked to bring the civil war to an end, so that his subjects could be reconciled. It had been necessary to use the tool of war at the start of his reign, but this was no longer an appropriate remedy to the affliction which beguiled France.[23] If he could not deliver relief to his beleaguered subjects, he urged god to end his reign. For god had made him king so that he might provide grace and blessings to his people, not wrath.[96] If he were thus to relieve his subjects from their burdens he would feel the 'greatest glory and happiness'.[97] He concluded his speech by saying that as king he enjoyed a special relationship with god, but that this also gave him particular responsibilities to give an account of his office to god.[98]

The speech was delivered with a firm and deep tone, and played to his skills as an orator.[94] Many of the assembled delegates had a favourable impression of his speech.[96] Bodin spoke highly of it, while Guillaume de Taix, the dean of Troyes was 'moved to tears'.[99] However this favourability did not translate into political support for Henri's program during the Estates.[98]

It contrasted with the laborious speech that followed from the chancellor Birague.[75] Birague critiqued each of the Three Estates in turn for not preserving the kingdom from the crisis it found itself in. It was, he said, important the Estates were united in the coming days as otherwise the kingdoms ills could not be remedied. Birague highlighted that peace was necessary for the execution of reforms to the kingdom. He argued that it was necessary for the Estates to provide the crown money so that Henri could support his household and army. The crowns poverty being caused by the irresponsibility of the king's predecessors.[100][88]

Henri attempted to direct the deputies towards domestic reform proposals, having in mind administrative and fiscal packages.[36][8] He was also keen that any push to the resumption of war would come not from himself, but rather the Estates, as through this means he could better justify demanding money from them to support its prosecution.[100]

Speakers of the three orders

[edit]

With the Estates opened, each Estate separated to go to their individual deliberations, where they might prepare their 'harangues'. The First Estate took up residence in the church of Saint-Sauveur, the Second Estate established themselves in the château while the Third took a townhouse.[75] The First Estate elected as their speaker the archbishop of Lyon. For the Second Estate the baron de Sennecey was chosen. The Third Estate selected the Parisian lawyer Pierre le Tourneur who Latinised his name as Versoris. Versoris and the archbishop of Lyon would go on to be ardent ligueurs. Versoris enjoyed strong connections with the duc de Guise.[101]

On 11 December, the lone Protestant delegate among the nobility, Mirambeau went to the king and asked whether the rumours that a new St. Bartholomew's Day massacre was being planned were true. Henri assured him that this was nonsense. Henri would however write to the major provincial governors to let them know that a massacre was not his desire a few days later.[101]

Constitutional reform

[edit]Some of the delegates (mainly in the First and Second Estates) harboured radical ambitions for the sharing of royal authority between the king and the Estates General with the Estates holding the legislative authority. The initial vision of the First Estate was for a third of the royal council to be ecclesiastical men, a third men of the short robe, and a third men of the long robe. The Third and Second are not interested in this specific arrangement, and countered that the royal council be cleared of unworthy men. Though it did not feature in their cahiers the nobility did at some point propose that the royal council be composed of 24 nobles, 2 from each province of the kingdom according to Blanchefort.[102] At the instigation of the nobility on 9 December a more balanced proposal was devised.[103] The First and Second Estates proposed that the royal council should be composed of deputies from the three orders, twelve of each order in total.[104][105] This request had first been made by the nobility back in the Estates General of 1560.[106]

This was a bold ambition, and one which required a demand of the king which was not normally the prerogative of the Estates to conduct. Therefore, at the recommendation of the archbishop of Paris it was decided to be make this request verbally and not in writing.[107][108] There were some however who feared to challenge the crown too openly during a time of civil war. The Third Estate, which was approach by the First and Second to support this policy was also hesitant about these demands, fearing that they could cement the authority of the First and Second Estates. This view was expounded by Bodin who argued in favour of two Estates not being able to decree by majority something to the disadvantage of the Third.[109][110] There were also concerns among the moderate deputies that by granting primacy to the Estates in this manner, there would be a risk that if the Estates were seized by a radical faction that this radical faction could thereby control the politics of the state.[111]

Regardless of their eventual consent, the Third Estate hoped that they would wait until the drafting of their cahiers before making such a proposal to the king. However, the archbishop of Lyon acting as speaker for the 36 delegates brought the proposal (which was written up by the noble deputy Pierre de Blanchefort) to Henri on 12 December.[112] Henri responded generously to the broad proposals. He was, he said, despite the fact this was an unusual and non customary request, willing to provide a list of those members of his conseil privé to the Estates for their opinions as to worthiness.[108] He would also receive 36 deputies to his council. He avoided however fully committing to the proposals presented to him, as concerned the notion that if the Estates were unanimous he would have to accede to whatever it was they were unanimous on, as this would have effectively reduced him to the position of a constitutional monarch. He reserve the right to ignore the Estates even in unanimity.[107][66] By his generous response, Henri hoped that he would soften up the Estates to the prospect of a financial subsidy.[63]

That same day, the speaker of the Second Estate, the baron de Sennecey approached the king and informed him that he thought a war to establish religious unity was a bad idea. Though it was not yet time for the Estates to vote on the matter it was unnerving for the king to have this opposition from the speaker.[113]

On 17 December, Henri sent the procurer général Jacques de La Guesle before the Estates. La Guesle informed the assembled delegates that Henri wished in theory to have absolute power to do good by his kingdom, but he is very happy that his authority and power has its limits. This aroused an indignant response from the dean of Troyes that this statement was merely an attempted response to the rumour that was circulating that Henri wished to rule as he saw fit without any checks on his authority.[111]

General interests of the Estates

[edit]The First Estate was largely united behind their concerns about the Protestants. They were keen to see the implementation of the Tridentine decrees, but also spent much of their time opposing the royal governments attempts to implement thoes reforms, as it related to infringements on their prerogatives. There was frustration in the First Estate that the kings had not abided by the Ordinance of Orléans which established an election process for ecclesiastical office. Not all the First Estate were disappointed by this, some bishops preferring royal appointment to the will of the masses.[114] There was also a desire to see the Ordinance of Villers-Cotterêts which limited the purview of ecclesiastical courts abolished, with many of their cahiers demanding this. However the two other Estates wished for further limitations of church courts.[115]

The Second Estate was more united than it had been in the Estates General of 1560-1 but had little solutions to offer the kingdom beyond remedies for their own immediate problems. They were primarily concerned that too many were buying their way into nobility. As for broader matters, they naïvely urged that the entire financial bureaucracy be abolished. They further demanded that foreigners be prohibited from the business of tax farming and that the crown cease to manipulate the currency.[116]

The Third Estate came to the Estates General with a somewhat expanded level of understanding of the interlocked fiscal, social and religious problems that impacted the kingdom, and some of the methods that could be used to combat this, built upon lessons learned from the Estates General of 1560.[117]

Suppression of Protestantism

[edit]Henri was keen to overturn the peace he had been forced into, but he looked to the Estates to provide him the funds to do so. The First Estate was the most vociferously committed to the destruction of the edict of Beaulieu. They were unanimous that Henri maintain unity of religion in the kingdom. They were also willing to provide financial support to see this brought about in the form of alms. The Second Estate was nearly as unanimous, however a small handful of deputies around six in total (Mirambeau, the sieur de Racan, seigneur de Blanchefort, sieur de Landigny, seigneur de Poussay and sieur de La Mothe-Massilly)[113] argued in favour of maintaining the kingdom in peace. There was also support for banning Protestantism but maintaining an allowance for freedom of conscience.[118] The Second Estate had much to gain in a resumption of war, with the opportunities of military glory and new commissions.[87] Therefore, the First Estate voted in favour of the outlaw of Protestantism on 22 December, the Second Estate several days earlier on 19 December.[66][41]

In the Third Estate, there would be considerably more dissension on what course to follow.[65] One faction desired a declaration of war on the Protestants. This group was represented by the Parisian lawyer Versoris. They were not unanimous however, and the anti-ligueur Jean Bodin, of the baillage of Vermandois, argued that unity of religion should be brought about by more pacific means. Bodin relied on the cahiers his constituency had sent him to the Estates with, which argued in favour of a religious council in two years to reunify the church.[119] The two debated the matter on 15 December, eventually agreeing that religious unity was desirable. Bodin was however able to convince the Estate to oppose the raising of taxes to fight a war on heresy. There was much agreement that an increase in taxation would be undesirable.[65] Therefore, the Third Estate agreed by a small majority in the end that uniformity of religion should be brought about and that it should be attained by 'gentle and holy ways which his majesty will devise'.[99][60] The attempt to specifically specify that those 'gentle ways' precluded war failed however, and on 26 December the Third Estate concluded that Protestantism should be suppressed in both public and private worship.[120] Bodin would propose that the king supplement his incomes through a direct tax on the First and Second Estate however this was too radical to be adopted.[121] There was precious little support in the Estate for any taxes to fight such a war.[65][122][8][123]

On geographic grounds, the Third Estate of Bretagne, Bourgogne, Guyenne, the Lyonnais, and Dauphiné supported the restoration of religious unity, but without supporting a war to bring this to pass. Meanwhile, the Third Estate of Normandie, Picardie, Languedoc, Provence, Champagne, the Île de France, and the Orléannais supported the kings position and allowed for the possibility of war to be on the table.[122] On 26 December the majority voted for the suppression of Protestantism be it public or private and that ministers be banished from the kingdom.[60]

Court intrigue

[edit]The rivalry between the entourages of Henri and Anjou was not quieted for the duration of the Estates. On 20 December a client of Anjou's assassinated Saint-Sulpice, a favourite of the kings. Though there was considerable grief in the court for the dead Saint-Sulpice, the prosecution of the murderer struggled considering the untouchable nature of Anjou.[124]

During December, Henri decreed that Princes du sang held precedence over all other princes in the kingdom. This royal attempt to regulate the nobility would see opposition from the Second Estate during January. It also had the effect of subordinating the duc de Guise to other princes for the proceedings of the Estates, and he therefore refused to attend.[125][126]

Beaulieu overturned

[edit]

On 29 December, Henri gave a speech to his council in which he declared that he had at his coronation sworn to protect the sole practice of the Catholic religion in France. He had made this declaration in front of Anjou, Navarre and all the peers of France. Henri stated that the only reason he had established the edict of Beaulieu was to re-secure Anjou for the royal cause and see France relieved from the marauding mercenary soldiers that plagued the kingdom.[120] It was however his intention as soon as it was practical to establish a single Catholic faith in France.[127] Going forward Henri vowed to never allow himself to be constricted to such an oath contrary to his coronation.[118] Anjou was present at this council meeting and according to the duc de Nevers indicated himself as being in favour of the re-establishment of religious uniformity.[128]

Bellièvre argued against this idea in the council, arguing that such a promise would engage him in an eternal war against his Protestant subjects (unable to make any treaty with them), and further make him unable to deal with foreign princes of the Protestant faith diplomatically.[118]

Review of the finances

[edit]On 31 December, Antoine de Nicolai, the premier président (first president) of the chambre des comptes (chamber of accounts) provided a summary on the crowns financial situation to the deputies. He blamed the penury of the crown on the preceding reigns of Henri II, François II and Charles IX.[129] There was some suspicion among the Estates that Nicolai's summary was not entirely accurate, an assessment which may have been correct if Nevers is to be believed, he characterises Henri as informing Nicolai to ensure that the Estates could not gain a full understanding of the situation.[129]

In addition to this summary, at Henri's invitation twelve deputies from each Estate were invited to look at the debts of the crown and propose possible ways in which the realms finances could be reorganised. The delegates refused to do this, and collectively challenged Nicolai as to the figures he had provided them with.[40] They decided to instead conduct an inquest into royal expenditure.[92] The Second Estate deputies were of the opinion from their examination that the king could support an army if he raised the taillon, however this ran into the opposition of the Third Estate deputies who argued that the taillon should be abolished and the taille reduced.[130] On 9 January the commission provided its report to the Estates in which they blamed the financial crisis on the extravagance of the court and the alienation of the royal domain.[131][132]

Embassies to the princes

[edit]

Henri decided to send out embassies to the errant princes on 1 January in response to the growing disorder in the south. Henri asked the Estates to elect deputies to treat with Condé, Navarre and Damville.[133] The language of address that was to be used upon greeting Navarre and Condé devolved into a matter of significant debate among the deputies, who eventually agreed that as they were greeting the princes as the embodiment of France itself they could drop some of the more obsequious language, this was at least the theory of the First Estate deputy Guillaume de Taix.[134] The decision was therefore taken not to describe themselves as 'very obedient' as such language was only appropriate to be directed by themselves towards their king. Condé was addressed by 'his most humble servants'. Though still technically deferential these were provocative addresses towards such princes.[135]

The delegation to Navarre was to inform him that the kingdom being solely Catholic was not merely an ancient custom of the kingdom but in fact the most fundamental law of France. This law was so fundamental that even Henri had no power to change it without the consent of the Estates.[110] The deputies were to further inform the princes that Henri did not have the power to conclude the Edict of Beaulieu without the consent of the Estates, and with their decision to reject the peace, it was a dead letter. Navarre and Condé were to be reassured that assuming they responded peacefully to the decisions of the Estates, they would in no way be prejudiced, and that they conscience and property would be protected.[136] The deputies departed on their diplomatic mission several days later, on 6 and 7 January.[137]

In a clarification sent to his foreign ambassadors in England and the Empire on 2 January, Henri let it be known, that his desire to see unity of religion in France did not preclude his dealings with them. He respected that they had established a unity of religion in their own countries where they reign 'happily and peacefully'.[138]

That same day, Nevers made his case to Henri that he must commit to the destruction of Protestantism and the reunification of a single Catholic faith in France. He argued it on the grounds of the king's coronation oath. He argued though that the initiative for such a war came from Henri alone, and not the authority of the Estates General.[139] In Nevers' estimation the Protestants could not object to him voiding the Edict of Beaulieu as that edict directly contravened the oath the king had made to god. When he did acknowledge the decisions of the Estates in his argument, he falsely implied they were unanimous in their desire for a war against Protestantism.[140] Nevers' vision of this war was fundamentally different from those wars which had gone before, it was to be a crusade of the entire kingdom.[141] The Protestantism of France were akin to the 'Turk' or 'infidel' in Nevers' reckoning.[142]

Campaign against the Protestants

[edit]This decision of the royal council was made public on 3 January, with Henri promising to lead a new campaign against heresy in the kingdom. Catherine wrote to her son in praise of the decision, but urged him to despatch a diplomatic effort to Navarre, Condé and Damville to see if they could be won over without the need for a new military campaign. If Navarre was difficult, she recommended Montpensier work on him. To sweeten the pot she proposed Montpensier offer Navarre a marriage between his sister and the duc d'Anjou. Condé once isolated would fold, but Damville would be trickier, Catherine opined she had the greatest fear of him due to his deeper experience.[143] On 15 January Henri wrote to the Pope and expounded upon his desire to see religious unity restored in France behind the Roman Catholic church. He therefore requested of Gregory a subsidy of 50,000 écus (crowns) per month to last for six months so that he might support an army.[96] The publication of this decision prompted the prince de Condé and king of Navarre to return to a state of rebellion.[144] Condé, denied the receipt of Péronne had already taken Saint-Jean-d'Angély on 13 August 1576 at the recommendation of Catherine.[145] Navarre meanwhile established himself at Agen. The Protestants began to terrorise Dauphiné and Provence at this time.[60]

Henri announced to the Estates on 11 January that Viviers, Gap, Die and Bazas had already fallen to the Protestants.[60] La Réole was also captured by the Protestants during December as the direction of the Estates became clear.[146] The archbishop of Embrun added to this that in Dauphiné only six of the twenty five towns stood for the Catholic faith and the king.[147] The war had also resumed in Poitou and Guyenne during December in response to the king's declarations.[148]

Catherine was by this point firmly in the party of peace, and declared as such in her meeting with Cardinal de Bourbon during January.[138]

While the Third Estate had initially committed itself to the destruction of Protestantism, the sudden successes of the resurgent Protestant military movement forced a re-evaluation. It was clear that this program could not be brought forth without an increase in taxation to see to its execution. Therefore, the Third Estate declared itself desirous of a peaceful policy.[147] Only the delegations of Picardie, Champagne and the Orléannais remained committed to a war to destroy Protestantism.[149]

'Final' plenary session

[edit]On 17 January the Estates were nominally meant to have concluded their discussions in a final plenary session. The king spoke again, and then a representative for each order spoke. The clergy had become more sympathetic to the royal cries for money, as many of their bishoprics in the south-east of France were increasing surrounded by Protestant controlled areas.[17] Therefore, the Archbishop of Lyon spoke in favour of providing money. He approved of the idea of religious reunification, however he spoke disapprovingly of the wasteful spending of the crown towards unworthy men who lacked merit. He further protested against the influence of Italian financiers (despite himself being close to many), he argued that the poverty of the crown was the boon of the financier.[116] Despite this he agreed that the clergy would provide 450,000 livres.[150] With this sum 1,000 gendarmes and 4000 foot soldiers would be supported for six months.[18]

The baron de Sennecey spoke for the Second Estate. He affirmed that it was the duty of the nobility to serve the crown, but that this needed to be built on a close relationship between the crown and nobility. The crown should therefore commit itself to the equitable distribution of honours among the nobility, and that such honours were not to be granted to foreigners. He ended his speech with a warning, reminding Henri that it was the nobility that first placed the crown on the heads of the kings of France. Despite being a fervent Catholic this speech channelled the arguments made by the Protestant Monarchomachs and was a forerunner to later arguments made by the Catholic ligue about royal authority.[125]

For the Third Estate Versoris spoke, he had been committed by the Estate to argue against his own position, in favour of the Estates new peaceful policy, however he could not bring himself in his speech to say that religious unity be accomplished without war. The deputies behind him began to protest against him and there was considerable disorder in the chamber which served to discredit Versoris and the war party, as the volume of the protest made clear they were now in the minority on their position.[147][136] Versoris' faltering performance during his speech made him a laughing stock.[151]

The war party in the Estates was further damaged by the growing awareness across the Estates of the vast financial problems that plagued the crown.[152]

Push for subsidies

[edit]However Henri was unwilling to see the Estates break up without being provided the subsidies necessary to conduct the war on heresy. He attempted to work on the deputies to push them towards supporting the idea, holding the prospect of offices and pensions in front of many.[123] The First Estate protested they had already provided a great sum. The Second Estate protested that their service took the form of arms, not money.[152] The Third Estate continued to protest, not without justification that the people were immiserated. Among the great lords, only a few zealous ones, such as the duc de Nevers were keen to offer their wealth. One of the queen's officers, named Châtillon proposed that all existing taxes be abolished and replaced with a single hearth tax that would vary based on the wealth of the household from 12 deniers to 30 livres, however this was rejected by the Third Estate without any discussion as it was felt it would simply be supplemented onto existing taxes.[18] The tax was theorised by its proposers to have raised 15,000,000 livres for the crown.[98] This would have surpassed the projected possible value of all other existing taxes France had presently, which was estimated to be around 14,000,000 livres.[153]

On 30 January, Henri dispatched his brother Anjou and the duc de Guise to work on the Estates. From the First Estate Anjou requested 400 foot soldiers and 100 horse which the Estate indicated it was willing to consider. From the Second Anjou and Guise were to secure from them a commitment to provide their military service for six months at their own expense. To inspire them, Anjou indicated he would be offering his military services. He finished his appeal by telling the deputies that he had now freed himself of Protestantism and was committed to strive towards the uniformity of religion in the kingdom under the Catholic faith.[154] However the Second Estate continued to move away from its interest in a new war.[132]

Eeach of the Estates presented to the king their cahiers de doléances on 7 February. The Third Estate cahiers included the matter brought to a head in December by which laws the king made in response to the requests of the Estates would be binding upon the king, thereby eroding his absolute power to ignore them in the future. The First Estate proposed that Estates meetings become regular, with the next occurring in two years due to the troubled situation of the kingdom (though in normal circumstances every five), the Second Estate proposed every two years, and the Third that the next occur in five years, but that it be a once in a decade occasion normally.[134] The idea of Estates called not at the direction of the king (in circumstances where the king was either a minor or incapable) had been put forward by some at the prior Estates of Pontoise and these proposals furthered that.[155]

All three Estates proposed that parlementaires be excluded from his council as it was their business to register laws, not make them.[92] The Third Estate argued that the tailles was an extraordinary tax, and should be treated as such as it was in the time of Louis X, not as the regular tax it was treated as by later kings.[121] The king was left in a dilemma, a majority of the Estates had supported overturning the establishment of religious uniformity, but only the clergy were willing to provide any money for this.[65] He urged the deputies to remain at Blois until such time as he could prepare the royal reply, but many deputies began to leave at this time.[132]

Return of the ambassadors

[edit]In February, the ambassadors that the Estates had sent to treat with the Protestant leaders returned. Those sent to treat with Condé returned first on 8 February. Condé had refused to receive them, and disregarded the legitimacy of the Estates at large in his rejection. Condé claimed that the crown had bought the votes to secure appropriately Catholic deputies and that the cahiers that had been prepared were forgeries.[146] The body was a 'corrupt puppet' in his estimation.[130]

The deputies who had travelled to meet with Navarre returned on 15 February.[156] Navarre had in contrast to Condé welcomed them, he was far less committed to the Protestant cause, and protested his loyalty to Henri, though on the matter of religious unity he demurred.[157][158] Navarre pointed out that Henri had sworn as king of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth to protect the Protestants that were subject to him, and denied (somewhat disingenuously) that Catholics were subject to persecution in his domains.[70] He emphasised his support for the recently negotiated peace. He added however verbally, despite the protests of the Protestant pastors in his company (who had it erased from his written declaration) that he was open to the restoration of a single religion in France.[159] Navarre stated 'if [my] religion is false, then let [my] opponents show it and I will adopt their faith'. By this means he left the door open to his eventual abjuration and adoption of Catholicism.[156] Despite his friendly Protestants, he was conducting a siege of the Catholic town of Marmande in January and it was only by departing this to travel to Agen that he met with the deputies that had been sent by the Estates to him (Pierre de Villars, the archbishop of Vienne, André de Bourbon, seigneur de Rubempré and the treasurer Mesnager).[48]

The delegation that travelled to Damville were the last to return on 26 February. Damville had protested his unshakeable Catholicism to them. He argued however the Estates were wrong to suggest Catholicism and Protestantism were incompatible as he was observing the Edict of Beaulieu in his governate. He argued to the deputies that great suffering would be brought about by overturning this arrangement at the advice of the Estates.[160]

The Estates were getting increasing eager to depart, and decided not to debate Navarre's response, claiming they were unable to have any opinion on it now that they had presented their cahiers.[160]

Henri proposed on 17 February that 18 deputies be invited to participate in his council for the discussion of how to proceed with the cahiers he had received. However this would be done without the council first being 'purified' of undesirable councillors by the Estates. The Estates refused this proposal.[110]

Alienation of the royal domain

[edit]On 20 February Henri recalled the Estates together and plead with them to permit him to alienate the royal domain to raise funds, proposing that he do so in such a way as to receive a perpetual annuity of 300,000 livres.[98] The First Estate and Second Estate both believed given the urgency of the circumstances such a course could be tolerated.[161] However, for Bodin and his faction of the Third Estate, the domain was inalienable, so this too went nowhere. Even if the other Estates might have agreed.[158][81] In frustration at Bodin for leading the opposition to the alienation of the royal domain, Henri dispossessed him of his role as maîtres des requêtes.[152]

Shortly before coming to the Estates General, Bodin had published his six livres de la république (six books of the republic) in which he argued that the king possessed a singular absolute power over the state. This power did not derive from divine right however, but had originally been held by the body politic as a whole, before it was delegated into the person of the king.[162][163] He emphasised in that work however that there were certain natural laws and the fundamental laws of the kingdom that the king did not have power over. Among these was the inalienability of the royal domain and the prohibition on inheritance through the female line.[162] It was on the grounds of the former that he opposed the king at the Estates General.[164]

With the failure of the alienation policy, Henri despaired, remarking 'they won't help me with their money, and they won't let me help myself with my money, its too cruel'.[132]

A grand ball was undertaken by the court on 24 February. The Gelosi theatre company were brought over from Italia (though kidnapped by Protestants on their way into France, Henri had paid their ransoms). Henri appeared at the grand ball dressed lavishly as a woman and wearing three rows of pearls with a diamond in his hat. The deputies of the Estates who had been pushing the king to reduce the expenses of his court required appeasement after this affair.[165]

Defeat of the war proposal

[edit]On 28 February Henri declared that he had no means to bring about the religious unity the Estates had initially desired of him. However, in the provinces the conflict with the Protestants had already started.[123] The duc de Nevers was bitterly disappointed by this admission from the king that it would not be possible to restore religious unity, and showed it openly. This prompted Catherine to remark ironically to him whether he wished for them to travel to Constantinople to prosecute his crusade.[166] Nevers, stung, replied that he had believed it was the king's intention to see Protestantism destroyed in France and that he was unaware Henri had changed his opinion. Catherine retorted that there had been no change of opinion, Henri simply lacked the means.[167] One of Nevers' (probable) clients, the Nivernais noble Pierre de Blanchefort had played a not insignificant role in sabotaging the Second Estates push to war.[168]

That same day the duc de Montpensier a delegate for the Second Estate and one of the most ardent persecutors of Protestants in the prior decade, delivered a surprising speech in the Estates. He had until recently been in the south, where he had been sent to diplomatically treat with Damville, and he had seen much of the consequences of the war.[157][169] He outlined the ruin France faced from continued attempts to enforce religious unity via war, and while assuring everyone that he would live and die a Catholic, proposed that toleration of Protestantism was the lesser evil, until such time a church council could reunify the Christians of France behind Catholicism once more.[170][69]

In his address he stated "When I consider the evils which the recent wars have brought us, and how much this division is leading to the ruin and desolation of this poor kingdom and the calamities such as those which I saw on my journey here... I am constrained to advise their Majesties to make peace... being the only remedy and best cure that I know of for the evil that has spread all over France."[171] Montpensier was not alone, with several deputies approaching the king that day to remonstrate against the overall decision in favour of war made by the Second Estate.[78] This remonstrance echoed that of Montpensier, arguing that while it was of course desirable for the kingdom to be reunified behind Catholicism, those who favoured civil war were ungodly. This remonstrance was signed by 20 nobles, around a quarter of those at the Estates General (only 75 nobles would sign their cahiers in early February meaning that it constituted more than a quarter by this metric), and was presented to the king by Montpensier.[172][69]

Nevers made one final appeal to the delegates from his duché of Nevers on 1 March, but was unable to convince them to provide funds to support a war effort.[173]

By the time the deputies departed at the start of March, the money the king had requested had not been provided.[150] He finally granted them permission to leave from 2 March to 5 March.[152]

Royal council of 2 March

[edit]Henri had got little of what he desired from the Estates General, yet on the royal council (on 2 March), the duc de Guise and duc de Nevers continued to urge him to reopen the war. Alongside them on the war party (according to Bodin) were the duc de Guise's brother, the cardinal de Guise and the duc de Mayenne. Opposing them on the council in favour of peace were Marshal Biron, Marshal Cossé, Montpensier, Morvillier and Bellièvre.[174] Henri protested to the war party that he had made every effort towards religious unity, but had not received the funds he needed from the Estates. Catherine argued in favour of peace in the council also, highlighting that the Protestants were taking city after city and he lacked the resources to prosecute a war against them. If the kingdom was destroyed in civil war, would not this also be a defeat for the unity of faith in the kingdom.[157][169] By now it was too late for such a change of heart however, as the resumption of the civil war was already a de facto reality on the ground. If he was to maintain any royal authority, it was necessary therefore to go to war.[175] With Damville and Anjou now somewhat loyal, the latter was to be the nominal commander of a royal army.[176][36] Instead of the grandiose ambitions he had harboured in December to see a unity of religion restored in the kingdom, it would be necessary to secure a renegotiation of the terms of the previous treaty he had concluded with the Protestants.[177][149] The war would be brief, and he would be able to secure more favourable terms.[178]

In March the king's mother Catherine succeeded in a political coup as Damville was brought over to the royal camp with the prize of the marquisate of Saluzzo dangled before him. To bring him around, Catherine also relied on the intermediary efforts of his elder brother, the duc de Montmorency and La Marck who interceded with her husband for Catherine.[179][178] As a royal governor and Catholic nobleman he had many differences of opinion with his nominal Protestant allies, thereby making his detachment possible.[176][73]

Sixth war of religion

[edit]By March the Protestants were already re-arming, and had conducted limited campaigns as early as December 1576.[176] With the Estates largely a failure to provide him the money for troops to fight the Protestants, Henri looked to the royal ligue for troops and funds, however enthusiasm was decidedly lacking. Each of the twelve provinces was to provide the funds for 3000 foot soldiers and 800 horse. In Bourgogne the meeting to arrange this was initially planned for March but there was so little interest it was not held until June. Dijon and Chalon made their disapproval clear, they understood the ligue to be a method by which Henri cut through their traditional privileges. Ultimately they would refuse to provide money.[180]

The duc d'Anjou agreed to lead a royal army against his former allies.[8][122] He was to lead it under the direction of the ducs de Nevers, Guise and Mayenne.[124] By his leadership, the crown hoped to demonstrate that he had ceased to be a friend of Protestantism. However the failure of the Estates to provide much in the way of funds left his army small and ill-equipped.[176]

The civil war that followed would be brief (only six months in duration), and brought to a close by the Edict of Poitiers on 17 September, which largely followed from the Edict of Beaulieu, but with greater restrictions on the areas in which Protestant worship could occur (one town per baillage + presently Protestant occupied cities). All ligues and associations were banned in the kingdom.[8][36][56] This peace was a significant success, in contrast with the earlier Edict of Beaulieu, and did not meet with significant opposition, the ligue movement would however survive in a reduced form, despite Henri's desires.[126] Going forward the ligue would be necessity be an underground organisation however.[181] Henri was greatly satisfied in a peace that he felt struck the right balance and allowed for the eventual reunification of the French church into a single religion.[182]

Legislative legacy

[edit]A proliferation of sub-governates had arisen since 1562, with the diocese of Castres alone being home to 24 governates. This had been the subject of complaints by the Third Estate at the Estates General, and Henri ordered all new governorships created since 1562 in Poitou (and possibly other areas) be abolished, though this would not come to pass.[183] The comte de Lude, overall governor of Poitou complained to the king of his failure to bring this to pass in 1577.[184]

The overbearing authority of the governor had also been critiqued by both the First and Third Estate, alongside complaints that they did not actually reside in their governates. Resultingly in 1579 Henri ordered lieutenant-generals (second in command to the governor, and acting governors during the absence of the governor) to permanently occupy their governates and provincial governors themselves to spend at least half of every years in their charges.[185] The Second Estate meanwhile complained about the practice of governors resigning their charges to a chosen successor. The crown did not immediately address this, and allowed the baron de Retz to resign the governorship of Provence to the comte de Suze in 1578, however in 1579 the edict of Blois prohibited the practice.[186]

Ordinance of September

[edit]While monetary stability had not been a particular concern of the Estates, it had nevertheless been a topic of discussion. The matter was something Henri was keen to address. Therefore, a debate was conducted in the town council of Lyon between the Italian financiers and the French merchants. The representative of the former, Antoine di Negro complained that the ability to conduct business in France was impeded by the instability, and that the écu d'or (gold crown) should be adopted, superseding the livre, which they proposed doing away with. The French merchants of Lyon were likewise concerned with stability, but violently disagreed with the suppression of the livre in favour of the écu d'or, they argued such a policy was designed to make it easier for the Italians to ship their bullion out of the kingdom. Henri sided with the argument of the former, and adopted the écu d'or for royal accounting, the result was a heavy wave of deflation much to the aggrievance of the debtors.[187] The continued civil wars further stopped the commercial rate of trading from matching the legal rate.[188]

In 1578, the number of royal councillors would be paired down. This was a response to criticisms levelled against the king in December by the Estates.[92]

Reaction to attacks on the Italians

[edit]In response to the complaints of the Estates about financiers, an attempt was made to suppress usury, however it was not pursued wholeheartedly.[189]