Sultanate of Aussa

Sultanate of Aussa | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1734–1936[1] | |||||||||||

|

Flag | |||||||||||

Aussa on modern map of Africa | |||||||||||

| Capital | Aussa | ||||||||||

| Common languages | |||||||||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam | ||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||

| Sultan | |||||||||||

• 1734–1749 | Kedafu | ||||||||||

• 1927-1936[2] | Mohammed Yayyo | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Early modern period to Interwar period | ||||||||||

• Established | 1734 | ||||||||||

• Disestablished | 1936[1] | ||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||

• Total | 76,868 km2 (29,679 sq mi) | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | Ethiopia | ||||||||||

The Sultanate of Aussa was a kingdom that existed in the Afar Region in eastern Ethiopia from the 18th to the 20th century. It was considered to be the leading monarchy of the Afar people, to whom the other Afar rulers nominally acknowledged primacy.

The Ethiopian Empire nominally laid claim to the region but were met with harsh resistance. Due to their skills in desert warfare, the Afars managed to remain independent, unlike other similar groups in the region.[3]

The Sultan Yayyo visited Rome along with countless other nobility from across East Africa to support the creation of Italian East Africa.[4] This marked the end of the region's independence and it was disestablished and incorporated into Italian East Africa as a part of the Eritrean Governorate and the Harar Governorate.

History

[edit]Imamate of Aussa

[edit]Afar society has traditionally been divided into petty kingdoms, each ruled by its own Sultan.[5]

The Imamate of Aussa was carved out of the Adal Sultanate in 1577, when Muhammed Jasa moved his capital from Harar to Aussa (Asaita) with the split of the Adal Sultanate into Aussa.[6]

In 1647, the rulers of the Emirate of Harar broke away to form their own polity. The Imamate of Awsa was later destroyed by the local Mudaito Afar in 1672. Following the Awsa Imamate's demise, the Mudaito Afars founded their own kingdom, the Sultanate of Aussa. At some point after 1672, Aussa declined in conjunction with Imam Umar Din bin Adam's recorded ascension to the throne.[6]

Sultanate

[edit]In 1734, the Afar leader Data Kadafo, head of the Mudaito clan, seized power and established the Mudaito dynasty after overthrowing the Harla led Adal Sultanate which had occupied the region since the thirteenth century.[7][8][9] This marked the start of a new and more sophisticated polity that would last into the colonial period.[9] The primary symbol of the Sultan was a silver baton, which was considered to have magical properties.[10] The influence of the sultanate extended into the Danakil lowlands of what is now Eritrea.[11]

After 15 years of rule, Kadafo's son, Muhammäd Kadafo, succeeded him as Sultan. Muhammäd Kadafo three decades later bequeathed the throne to his own son, Aydahis, who in turn would reign for another twenty-two years. According to Richard Pankhurst, these relatively long periods of rule by modern standards pointed to a certain degree of political stability within the state.[9]

Aussa's prosperity was coveted by Afars from neighbouring lands and in particular the Debne-Wemas, the strongest of the southern Adoimara.[12] In the last decade of the 18th century they wished to capture the capital therefore they enlisted in the support of a number of Yemen matchlockmen from Aden. According to Krapf and Isenberg, were no less than a few hundred strong and enjoyed a complete monopoly of firepower.[13]

William Cornwallis Harris had stated that the town's defence was organised by the ruler Yusuf ibn Idjahis, a brave and martial sultan, whose armoury boasted several cannons and matchlocks. He claimed that the defenders caught the would-be attackers off guard, while they were sleeping and cut all the throats of "all save one".[14] The Debne-Wemas, according to this account were not intimidated by this reverse returned with fresh allies from the coast that they rallied and had achieved a murderous defeat of the Mudaitos. Yusuf was slain after which the town was sacked and the garrison was put to the sword.[12]

The instability from this invasion had caused the Aussa state to suffer greatly. Aussa, once an important place had lost much of its political significance but had remained an extensive encampment frequented by innumerable Afars and Somalis as a place for perpetual fairs.[12][15]

Sultan Mahammad ibn Hanfadhe defeated and killed Werner Munzinger in 1875, who was leading an Egyptian army into Ethiopia.[16]

Colonial period

[edit]In 1869, the newly unified Italy bought Assab from a local Sultan (which became the colony of Eritrea in 1890), and led Sultan Mahammad to sign several treaties with that country. As a result, the Ethiopian Emperor Menelik II stationed an army near Aussa to "make sure the Sultan of Awsa would not honor his promise of full cooperation with Italy" during the First Italo–Ethiopian War.[17]

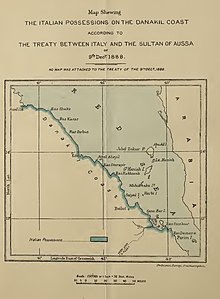

Count Tornielli declared to the Marquis of Salisbury that Article 5 of the treaty concluded between the Italians and the Sultan Mahammad Hanfare. That in a case of any other power trying to occupy Aussa or any parts of his territory, the Sultan must oppose it and declare that his nation is an Italian protectorate and must raise the Italian flag.[18] According to Article 3, the Sultan had recognised the whole Danakil coast from Amphila Bay to Ras Doumeira as an Italian possession and had conceded the territories of Gambo Kona and Ablis as a part of Italian Eritrea.[19][20]

Second Italo-Abyssinian War

[edit]During the Second Italian-Ethiopian War, the Sultan Mahammad Yayyo agreed to cooperate with the Italian invaders.[21]

By 1 April 1936, Italian troops completed the occupation of the rich Sultanate of Aussa, bordering on French Somaliland.[1] As a result, in 1943 the reinstalled Ethiopian government sent a military expedition that captured Sultan Muhammad Yayyo and made one of his relatives Sultan.[22] Upon a visit to Rome, Sultan Mohamed Yayyo met Benito Mussolini and declared a speech of his loyalty towards the Italian Empire in Palazzo Venezia.[23]

Duce, dal tempo più lontano, la mia famiglia e state nemica degli abissini, nemici della potenti Italia. Mio nonno e mio padre sono sempre stati amici dell'Italia ed io, con il cuore e con la spada, sono un soldato dell'Impero italiano. Per la mia fedelta ho chiesto il premio di vedervi Oggi Vi vedo ed ho la gioia di ripetere a Voi il giuramento di fedelta mio della gente della mia razza. Ripotero al mio Paese la Vostra immagine e la Vostra parola. Dio benedica la Vostra opera e ci mantenga sulla giusta via della Vostra Volontà. Io Vi offro questo tappeto che fu gia del Negus Micael e che poi, Ligg Jasu dono mio padre: sono lieto che questo tappeto, fatto per i sovrani abissini, sia oggi proprieta del Fondatore dell'Impero |

Duce, from the earliest times, my family has been an enemy of the Abyssinians, enemies of mighty Italy. My grandfather and my father have always been friends of Italy, and I with heart and sword, am a soldier of the Italian Empire. For my fidelity I have asked for the reward of seeing you Today I see you and I have the joy of repeating the oath to you of my allegiance of the people of my race. I will repeat your image and your word to my country. God bless your work and keep us on track way of your will. I offer you this carpet which was already by the Negus Mikael and which later, Lij Iyasu gifted to my father: I am delighted that this rug, made for the Abyssinian sovereigns, is today property of the Founder of the Empire. |

| —Sultan Yayyo's speech to Benito Mussolini |

Revival within modern Ethiopia

[edit]Sultan Alimirah often came into conflict with the central government over its encroachment on the authority of the Sultanate. Aussa, which had been more-or-less self-governing until the Sultan's ascension in 1944, had been greatly weakened in power by the centralising forces of Haile Selassie's government. In 1950 he withdrew from Asaita for two years in opposition, returning only two after following mediation by Fitawrari Yayyo.[24] The Sultan sought to unite the Afar people under an autonomous Sultanate, while remaining part of Ethiopia; they had been divided amongst the provinces of Hararghe, Shewa, Tigray, and Wollo.[25]

In 1961, when it was clear the Eritrean federal arrangement was headed towards its demise, 55 Afar chieftains in Eritrea met and endorsed the idea of an Ethiopian Afar autonomy. Following the dissolution of Eritrea's federal government and its transformation into a centrally-administered province, Afar leaders met again in Assab in 1963 and supported the creation of an autonomous region. In 1964, Afar leaders went to Addis Ababa to present Haile Selassie with their proposal, but the effort came up empty-handed.[25] Despite these encroachments and conflicts, the Sultan remained fundamentally loyal to the Emperor and Ethiopia; in turn, while he did not achieve the autonomous sultanate he desired, he enjoyed an appreciable level of autonomy in the areas of the Sultanate, almost unique amongst the many petty kingdoms incorporated into the Ethiopian state in the late 19th century. For example, while the government appointed a governor to the awrajja (district) of Aussa proper, the governor, rather than taking up residence in the capital of Asaita, instead sat in Bati, which was outside the district entirely.[26]

In 1975, Sultan Alimirah Hanfare was exiled to Saudi Arabia, but returned after the fall of the Derg regime in 1991. Upon Alimirah Hanfere's death in 2011, his son Hanfere Alimirah was named his successor as sultan.[27]

Religion

[edit]The religious elites of Aussa commonly carried the honorific title Kabir.[28]

List of Sultans

[edit]- Kandhafo 1734–1749

- Kadhafo Mahammad ibn Kadhafo 1749–1779

- Aydahis ibn Kadhafo Mahammad 1779–1801

- Aydahis ibn Mahammad ibn Aydahis 1801–1832

- Hanfadhe ibn Aydahis 1832–1862

- Mahammad "Illalta“ ibn Hanfadhe 1862–1902

- Mahammad ibn Aydahis ibn Hanfadhe 1902–1910

- Yayyo ibn Mahammad ibn Hanfadhe 1902–1927

- Mahammad Yayyo 1927–1944

- Alimirah Hanfare 1944–1975, 1991–2011

- Hanfare Alimirah 2011–2020

- Ahmed Alimirah 2020–present

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b "ITALIANS CONQUER AUSSA SULTANATE; Occupy Sardo, in Center of Rich Area, and Dominate Red Sea Caravan Trails. LINE BISECTS ETHIOPIA Rome Sees Early Submission of Haile Selassie -- Britain's Attitude Chief Worry". The New York Times. April 1936.

- ^ https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Recalling-the-history-of-Sultan-Mohammed-Hanfare-he-Berihun-Jemal/7d2bede3af67791fe78a9f7445e5242f518392d0/figure/0

- ^ Thesiger, Wilfred (1935). "The Awash River and the Aussa Sultanate". The Geographical Journal. 85 (1): 1–19. doi:10.2307/1787031. JSTOR 1787031.

- ^ Sbacchi, Alberto (1977). "Italy and the Treatment of the Ethiopian Aristocracy, 1937-1940". The International Journal of African Historical Studies. 10 (2): 209–241. doi:10.2307/217347. JSTOR 217347.

- ^ Matt Phillips, Jean-Bernard Carillet, Lonely Planet Ethiopia and Eritrea, (Lonely Planet: 2006), p.301.

- ^ a b Abir, p. 23 n.1.

- ^ Bausi, Alessandro. Ethiopia History, Culture and Challenges. Michigan State University Press. p. 83.

- ^ Abir, pp. 23-26.

- ^ a b c Pankhurst, Richard (1997). The Ethiopian Borderlands: Essays in Regional History from Ancient Times to the End of the 18th Century. Red Sea Press. ISBN 0932415199.

- ^ Trimingham, p. 262.

- ^ AESNA (1978). In defence of the Eritrean revolution against Ethiopian social chauvinists. AESNA. p. 38. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

Later in their history, the Denkel lowlands of Eritrea were part of the Sultanate of Aussa which came into being towards the end of the sixteenth century.

- ^ a b c Pankhurst, Richard (1997). The Ethiopian Borderlands: Essays in Regional History from Ancient Times to the End of the 18th Century. The Red Sea Press. p. 394. ISBN 978-0-932415-19-6.

- ^ Abir, Mordechai (1968). Ethiopia: the Era of the Princes: The Challenge of Islam and Re-unification of the Christian Empire, 1769-1855. Praeger. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-582-64517-2.

- ^ Harris, Sir William Cornwallis (1844). The Highlands of Æthiopia. Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans. pp. 179–180.

- ^ Harris, Sir William Cornwallis (1844). The Highlands of Æthiopia. Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans. p. 180.

- ^ Edward Ullendorff, The Ethiopians: An Introduction to Country and People, second edition (London: Oxford University Press, 1965), p. 90. ISBN 0-19-285061-X.

- ^ Chris Proutky, Empress Taytu and Menilek II (Trenton: The Red Sea Press, 1986), p. 143. ISBN 0-932415-11-3.

- ^ Hertslet, Sir Edward (1967). The Map of Africa by Treaty: Nos. 95-259: Abyssinia to Great Britain and France (3 ed.). Great Britain: Cass. p. 453.

- ^ Hertslet, Sir Edward (1967). The Map of Africa by Treaty: Nos. 95-259: Abyssinia to Great Britain and France (3 ed.). Great Britain: Cass. p. 458.

- ^ Hertslet, Sir Edward (1967). The Map of Africa by Treaty: Nos. 95-259: Abyssinia to Great Britain and France (3 ed.). Great Britain: Cass. p. 448.

- ^ Anthony Mockler, Haile Selassie's War (Brooklyn: Olive Branch Press, 2003), p. 111.

- ^ Trimingham, p. 172.

- ^ Mussolini, Benito (1939). Scritti E Discorsi Di Benito Mussolini Volume 12. pp. 214–215.

- ^ "Sultan Ali Mirah Hanfare Passed Away". Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- ^ a b Yasin, Yasin Mohammed (2008). "Political history of the Afar in Ethiopia and Eritrea1" (PDF). GIGA Institute of African Affairs. 42 (1): 39–65. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- ^ Zewde, Bahru (March 2012). "Ethiopia: The Last Two Frontiers (Review)". Africa Review of Books. 8 (1): 7–9.

- ^ AFAR News Toronto v.01 (July 2011) Archived 2016-04-14 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Houmed Soulé, Aramis (12 January 2018). "II. La légende d'Awdaḥis et la dynastie des Aydâḥisso". Deux vies dans l’histoire de la Corne de l'Afrique : Les sultans ‘afar Maḥammad Ḥanfaré (r. 1861-1902) & ‘Ali-Miraḥ Ḥanfaré (r. 1944-2011) (in French). Centre français des études éthiopiennes. pp. 11–18. ISBN 978-2-8218-7233-2.

References

[edit]- Mordechai Abir, The era of the princes: the challenge of Islam and the re-unification of the Christian empire, 1769-1855 (London: Longmans, 1968).

- J. Spencer Trimingham, Islam in Ethiopia (Oxford: Geoffrey Cumberlege for the University Press, 1952).