Kiichi Okamoto

Kiichi Okamoto | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 12 June 1888 |

| Died | 29 December 1930 (aged 42) Tokyo Prefecture, Japan |

| Education | Hakubakai |

| Known for | Illustration for children |

| Movement | Yōga |

Kiichi Okamoto (Japanese: 岡本 歸一, romanized: Okamoto Kiichi; 12 June 1888 – 29 December 1930) was a Japanese painter best known for his illustrations for children.

Early life

[edit]Okamoto was born in Sumoto on Awaji Island in 1888. He and his family moved to Tokyo in 1892 for his father's promotion to the vice-president of Miyako Shimbun.[1] When in elementary school, Okamoto encountered hand fans with beautiful paintings which fascinated him and motivated him to study painting.[2]

In 1906, he was apprenticed to Seiki Kuroda to study yōga at the age of 18.[1] Among his fellow pupils was Ryūsei Kishida, with whom Okamoto formed an artists' group and named it Fusain Society (Fyūzankai) to promote post-impressionism.[3] Enthralled by Vincent van Gogh and Paul Cézanne, they held an exhibition challenging the conservative Bunten in 1912.[1][3][4] It angered Kuroda and brought an end to their mentoring relationship, leading to the split of Fusain Society.[1][5] Nevertheless, Okamoto and Kishida organized a new group together with Shōhachi Kimura and Kōtarō Takamura to give an exhibition of their own paintings in October 1913.[6]

Okamoto was also active in the sōsaku hanga movement. The influence of William Nicholson can be seen in his hanga Portrait of N.O.[7] He was also influenced by Edmund Dulac and Arthur Rackham.[1]

Career in children's media

[edit]

In 1914, upon his marriage, Okamoto moved next door to Kusuyama Masao, a popular theater critic and translator of Western literature.[8][9] Kusuyama helped Okamoto expand his activities to include stage design, and also asked Okamoto to draw illustrations for a series of juvenile novels Mohan Katei Bunko, of which he was the editor-in-chief, in 1915.[1][10]

Okamoto began drawing for Kin no Fune, a magazine of children's literature and songs, in 1919.[1] Knowing Ujō Noguchi through his jobs, Okamoto drew illustrations for Noguchi's works.[10]

In 1922, Okamoto was named chief illustrator for Kodomo no Kuni from its second issue.[1] Kodomo no Kuni was sold at a half yen per copy, relatively expensive compared to rival magazines, but was enough competitive due to its high quality of the pictures.[11] Among the ardent readers were Chihiro Iwasaki and Seiichi Horiuchi, who would become leading illustrators for children in the mid-Shōwa period. Horiuchi admired Okamoto's ability to capture facial expressions.[12]

Kodomo no Kuni was completely different from any other book I had ever read. A picture of beautiful evening primroses looked as if they were whiffling with scent in the dusk ... I fell in love with Okamoto's pictures ...

Starting to work for Shōjo Club in 1923 and for Kodomo Asahi in 1924,[1] Okamoto became the most popular illustrator for children in Japan in the 1920s.[9] In 1927, he participated in forming the Japan Association of Illustrators for Children with Takeo Takei, Tomoyoshi Murayama and other painters.[1][10]

He had been busy with his work until just a few days before he died of typhoid fever at the age of 42 in Tokyo.[10]

Family

[edit]Okamoto married Kishiko in 1914 and had two sons. His elder son, Hajime, became a professional yacht photographer.[15]

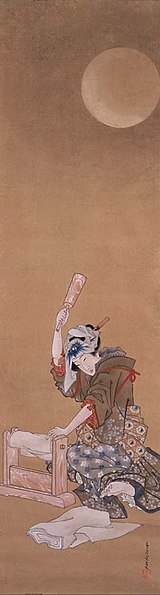

Gallery

[edit]-

Straw Millionaire (1916) in Kunio Yanagita's book of folktales.

-

Rabbits' Dance (1924) with Ujō Noguchi's lyrics.

-

Building a Radio (1928). Okamoto introduced then-newest technology in some of his pictures.[10]

-

Best Friends (1931), one of his posthumous works.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "OKAMOTO Kiichi". Kodomo no kuni. Tokyo: International Library of Children's Literature, National Diet Library. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- ^ Takesako, Yūko (2001). "モダンの空間". In Takesako, Yūko; Ishiko, Jun; et al. (eds.). 岡本帰一 思い出の名作絵本 (in Japanese). Kawade Shobō Shinsha. pp. 85–86.

- ^ a b Kondō, Yū (2011). 洋画家たちの東京 (in Japanese). Sairyūsha. p. 235.

- ^ Takesako (2001), pp. 87–88.

- ^ Takesako (2001), p. 89.

- ^ Kimura, Shōhachi (1949). "私のこと". 東京の風俗 (in Japanese). Tokyo: Mainichi Newspapers.

- ^ Ajioka, Chiaki (2000). Hanga: Japanese Creative Prints. Sydney: Art Gallery of New South Wales. p. 41.

- ^ Takesako (2001), pp. 90–91.

- ^ a b Kami, Shōichirō (1994). 日本の童画家たち (in Japanese). Kumon Publishing. pp. 51–54.

- ^ a b c d e f 岡本帰一. コドモノクニ (in Japanese). Tokyo: International Library of Children's Literature, National Diet Library. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- ^ "File109 レトロな絵本". 鑑賞マニュアル 美の壺 (in Japanese). Japan Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- ^ Kishida, Eriko; Deguchi, Yūkō; Iwaya, Kunio (2009). Corona Books (ed.). 堀内誠一 旅と絵本とデザインと (in Japanese). Tokyo: Heibonsha. p. 28.

- ^ Takesako, Yūko (2009). ちひろの昭和 (in Japanese). Kawade Shobō Shinsha. p. 133.

- ^ Yamada, Miho (17 November 2010). ちひろとちひろが愛した画家たち (PDF). 美術館だより (in Japanese). 171. Chihiro Art Museum Tokyo: 2. ISSN 1884-7722. Retrieved 21 September 2013.

- ^ Kami, Shōichirō (1974). 聞き書・日本児童出版美術史 (in Japanese). Tokyo: Taihei Shuppansha. p. 96.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Okamoto Kiichi at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Okamoto Kiichi at Wikimedia Commons

![Building a Radio (1928). Okamoto introduced then-newest technology in some of his pictures.[10]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b8/Radio_okamotokiichi.png/120px-Radio_okamotokiichi.png)

![Basketball (1928). He learned silhouette cuts from Arthur Rackham's works.[10]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/ca/Basketball_okamotokiichi.png/120px-Basketball_okamotokiichi.png)