Julius Pomponius Laetus

Julius Pomponius Laetus (1428 – 9 June 1498), also known as Giulio Pomponio Leto, was an Italian humanist.

Background

[edit]Laetus was born at Teggiano, near Salerno, the illegitimate scion of the princely house of Sanseverino, the German historian Ludwig von Pastor reported.[1] He studied at Rome under Lorenzo Valla, whom he succeeded in 1457 as professor of eloquence in the Gymnasium Romanum. About this time he founded an academy (Accademia Romana), the members of which adopted Greek and Latin names,[2] and met at the house of Laetus on the Quirinal, which was filled with fragments and inscriptions and Roman coins collected by this early antiquarian, to discuss classical questions;[3] they celebrated the birthday of Romulus.[4] Its constitution resembled that of an ancient priestly college, and Laetus was styled pontifex maximus. Bartolomeo Platina and Filippo Buonaccorsi were among the most distinguished members of the circle, which also included Giovanni Sulpizio da Veroli, the editor of the first printed De architectura of Vitruvius and organizer of the first production of a Senecan tragedy mounted since Antiquity.

Controversy surrounding his academy

[edit]In 1466, on his way to take up an appointment at the University of Rome, Laetus stopped for a sojourn in Venice. Here he was brought under investigation by the Council of Ten on suspicion of having seduced his students, whom he was said to have praised with excessive ardour in some Latin poems. Charged with sodomy, he was imprisoned.[5]

At the same time in Rome, Pope Paul II began viewing Laetus's academy with suspicion, as savouring of paganism,[6] heresy, and republicanism. In 1468 twenty of the academicians were arrested during Carnival on charges of conspiracy against the Pope. Laetus, who was still in Venice at the time the supposed conspiracy was discovered, was sent back to Rome, imprisoned and put to the torture, but refused to plead guilty to the charges of infidelity and immorality. For want of evidence, he was acquitted and allowed to resume his professorial duties; but it was forbidden to utter the name of the academy even in jest. He also decided not to set foot in Venice again, and for greater security, soon married.

In the meantime, Laetus received from Frederick III a dispensation to grant the laurel wreath: the young poet Publio Fausto Andrelini from Forlì (Italy) was the first to receive it.

Laetus continued to teach at the University of Rome until his death in 1498. Pope Sixtus IV permitted the resumption of the Academy meetings, which continued to be held until the sack of Rome in 1527. Laetus's importance in cultural history lies mostly in his role as a teacher. On his death he was buried in the church of San Salvatore in Lauro in Rome.

Significance

[edit]Laetus, who has been called the first head of a philological school, was extraordinarily successful as a teacher; he said that he expected, like Socrates and Christ, to live on through his pupils, some of whom were many of the most famous scholars of the period. Among those put under his charge to be educated were Alexander Farnese, later pope Paul III. His works, written in sophisticated classicizing Latin,[7] were published in a collected form (Opera Pomponii Laeti varia, 1521). They contain treatises on the Roman magistrates, priests and lawyers, and a compendium of Roman history from the death of the younger Gordian to the time of Justin III. Laetus also wrote commentaries on classical authors, and promoted the publication of the editio princeps of Virgil at Rome in 1469.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Pastor IV 1894:41f.

- ^ The original Italian name of Pomponius Laetus is not even known.

- ^ Ludwig Pastor's remark, following his discussion of the torture and imprisonment of Platina, is revealing: "the meeting of these malcontents, and of the Heathen-minded Humanists, took place in the house of a scholar well known throughout Rome for his intellectual gifts and for his eccentricity" (Pastor IV 1894:41)

- ^ Raphael Volaterranus, in his Commentaries presented to Julius II, declared that the enthusiasms of these initiates were "the first step towards doing away with the Faith" (Pastor IV 1894:44).

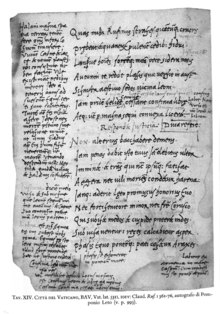

- ^ The existence in the Biblioteca Marciana in Venice of two Latin epigrams with sodomitical themes written by Laetus suggests that other writings of this sort may be rediscovered. See: Giovanni Dall'Orto, Giulio Pomponio.Leto, "La Gaya Scienza".

- ^ "These persons" Paul II's court biographer Canensius asserted, "despise our religion so much that they consider it disgraceful to be called by the name of a Saint, and take pains to substitute heathen names for those conferred on them in baptism." Quoted by Pastor IV 1894:48.

- ^ Palmer, Ada. "The Use and Defense of the Classical Canon in Pomponio Leto's Biography of Lucretius." Renaessanceforum, 2015. http://www.renaessanceforum.dk/rf_9_2015.htm

References

[edit]- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Laetus, Julius Pomponius". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 16 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 63–64.

- Catholic Encyclopedia article

- Pastor, Ludwig, The History of the Popes, from the Close of the Middle Ages vol. IV (1894) p 41ff.

- For articles on Pomponius Laetus and his humanist circle, see "The Repertorium Pomponianum," with bibliographies including: Accame, Maria. Pomponio Leto: vita e insegnamento (Tivoli [Roma]: Tored, 2008) and other recent publications.