Hua Sui

Hua Sui (simplified Chinese: 华燧; traditional Chinese: 華燧; pinyin: Huá Suì; 1439–1513 AD) was a Chinese scholar, engineer, inventor, and printer of Wuxi, Jiangsu province during the Ming dynasty (1368–1644 AD). He belonged to the wealthy Hua family that was renowned throughout the region. Hua Sui is best known for creating China's first metal movable type printing in 1490 AD.[1]

Metal movable type printing

[edit]Metal movable type printing had been invented in Korea during the earlier 13th century,[note 1] but there is no concrete evidence that suggests Hua Sui's metal type print was influenced by Korean printing.[1]

Earlier wooden and ceramic types

[edit]

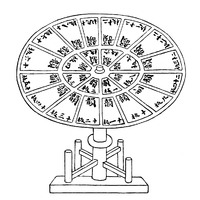

Movable type was invented and improved in China centuries before Hua Sui. As written by the polymath Chinese scientist Shen Kuo (1031–1095) of the Song dynasty (960–1279 AD), the commoner and artisan Bi Sheng (990–1051) was the first to invent movable type, with his ceramic type invented in the Qingli period (1041–1048).[2] During the Yuan dynasty (1279–1368 AD), the governmental magistrate and scholar Wang Zhen (fl. 1290–1333) was an early innovator of wooden movable type, as his process improved the speed of typesetting as well.[3] Much like Bi Sheng experimenting with wooden movable type in the 11th century but finding it unsatisfactory, Wang Zhen also experimented with metal type printing using tin.[4] Wang Zhen wrote in the book of the Nong Shu (1313 AD):

In more recent times [late 13th century], type has also been made of tin by casting. It is strung on an iron wire, and thus made fast in the columns of the form, in order to print books with it. But none of this type took ink readily, and it made untidy printing in most cases. For that reason they were not used long.[4]

Thus, Chinese metal type of the 13th century using tin was unsuccessful because it was incompatible with the inking process. Although unsuccessful in Wang Zhen's time, the bronze metal type of Hua Sui in the late 15th century would be used for centuries in China, up until the late 19th century.[5] Furthermore, a font of tin movable type was successfully employed by a Mr. Tong of Guangdong in the 19th century, who figured out how to make it more compatible with the inking process.[4]

Metal type of the Ming period

[edit]

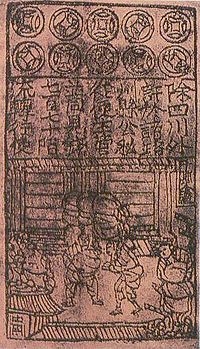

Hua Sui, who did not become a scholar until about the age of fifty, became interested in printing books.[6] He had accumulated a sizable fortune, and desired to use that fortune in order to establish the reputation as a printer in the region.[6] Hua Sui became the first of his familial clan to use his resources in establishing bronze-type printing in 1490. The first book printed in bronze-type in China was the Zhu Chen Zou Yi of that year (housed now in the National Central Library of Taipei, Taiwan), a simple collection of memorials printed in two editions.[6] The books printed by Hua Sui contain the signature Hui Tong Guan (Studio of Mastery and Comprehension), meaning he had mastered the process of metal movable type printing.[6] Including the Zhu Chen Zou Yi, published 15 titles using metal type, in a span of about 20 years.[6]

Family relatives of Hua Sui caught on and engaged in metal type printing as well. Hua Cheng (1438–1514 AD), a distant relative of Sui, an antiquarian, and book-collector, began his own printing studio known as Shang Gu Zhai (Studio for Esteeming Antiquities).[7] He printed the Bai Chuan Xue Hai of 1501 using metal type, and printed many rare books he obtained in a rapid process thanks to the speed of metal typesetting.[8] Hua Qian (fl. 1513–1516), a nephew of Hua Sui, was yet another bronze-type printer of the Hua family. His studio signature was Lan Xue Tang (Hall of Orchid and Snow), and his largest printing project was reprinting the old Tang dynasty encyclopedia of the Yi Wen Lei Ju (1515).[8] In addition, various members of the Hua family contributed to metal movable type printing, as about 24 book titles using metal type were published between 1490 and 1516.[8]

There was another prestigious family of Wuxi, Jiangsu province, who engaged in metal type printing. This was the An family, most notably that of An Guo (1481–1534).[8] However, the An family's printed works came shortly after the Hua family, the latter of whom were supposedly inspired by Shen Kuo's description of Bi Sheng's movable type in the Meng Xi Bi Tan (Dream Pool Essays) of 1088 AD. Yet the process of earthenware movable type and metal movable type are different, as metal movable type required many more complex technical processes of engraving, casting, type-setting, inking, and printing.[8]

Bronze type publications were soon after made in the cities of Changzhou, Suzhou, and Nanjing during the 16th century.[8] Yet the sponsors of printing weren't all described as the works of simply the area's wealthiest local family, as the bronze-type books in Fujian province were developed by truly commercial enterprises.[8] Chinese writing fonts of different sizes and scope could be jointly owned and invested in by more than one printer in the region.[8]

In addition to bronze, there were also other metal types used for movable type printing. Lu Shen (1477–1544 AD) once reported in the early 16th century that printers of Changzhou used bronze and lead movable type printing, which could have been separate materials or an alloy mixture of the two.[4]

The Qing period

[edit]During the Qing dynasty (1644–1911), the imperial court had made wooden movable type the official printing method, overseen by the official Jin Jian (d. 1794) who had 253,000 wooden movable type font characters made in 1733.[9] However, the Qing government also sponsored bronze-type printing, as they crafted 250,000 bronze characters earlier in 1725 to print the Gujin Tushu Jicheng (古今圖書集成, Complete Collection of Illustrations and Writings from the Earliest to Current Times).[1] The encyclopedia encompassed 5020 volumes in length, as sixty six copies of the encyclopedia were made.[10] Although the bronze characters were kept safe and deposited in the Wuying Palace, they were all melted down in 1744 in order to forge coin currency.[10]

Beyond the imperial court, there were many small private industries and individual sponsors of printing during the Qing period.[5] Chui-Li-Ge of Changshu was known to have printed a large literary collection of his in 1686 AD.[10] The Manchu military officer Wu-Long-A printed a collection of imperial edicts while stationed in Taiwan in the year 1807.[10] The Chinese character font of some 400,000 bronze characters made by Lin Chun Qi took twenty one years to make, from 1825 until 1846.[4] The total cost for the endeavor was 200,000 silver teals.[4] These characters were used to print a variety of different books, including treatises on phonology, medicine, and military strategy, and it is possible his same character font was used by the later Wu Chongjun of Hangzhou when he printed two other works in 1852.[4]

Process and methods

[edit]

For creating movable type font characters, the Chinese employed both methods of either casting moulds or individually engraving characters.[11] Casting was favored over the long and laborious process of cutting individual characters of bronze, which may have been a simple task with the material of wood, but not as economically feasible with metal that could be simply cast instead.[12] However, for traditional Chinese metal movable type printing, some records of the 18th century indicate that individual engraving and cutting was used as well.[13] While creating new books using movable type, ink was applied to a plate and rubbed with paper as seen in woodblock printing.[13] Then there was the process of assembling and setting the type, and ultimately distributing it, which necessitated at least a small level of division of labor.[13] In fact, there are books printed in the Ming and Qing periods that designated the lists of workers who contributed to the printing, publication, and distribution of the books themselves.[13] The bronze-type edition of the Song dynasty encyclopedia Tai Ping Yu Lan printed in 1547 AD, in the city of Jianyang, described how two persons were responsible for typesetting while two others were in charge of the actual printing.[13] For books that do not indicate in the initial pages whether they were printed using movable type instead of woodblock printing, there are definite signs that can be examined to deduce which method was used. Misprints, misalignment of characters, and uneven spacing are the distinct mark of many movable type editions from the time of Hua Sui.[14] However, as time progressed and the works of printers such as Hua Jian, An Guo, and others were made, steps were made to perfect the process and thus making it harder to differentiate between woodblock printing editions and movable type editions (unless noted in the text).[14]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ See the article History of typography in East Asia.

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c Needham, Volume 5, Part 1, 215.

- ^ Needham, Volume 5, Part 1, 201.

- ^ Needham, Volume 5, Part 1, 206–208.

- ^ a b c d e f g Needham, Volume 5, Part 1, 217.

- ^ a b Needham, Volume 5, Part 1, 216–217.

- ^ a b c d e Needham, Volume 5, Part 1, 212.

- ^ Needham, Volume 5, Part 1, 212–213.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Needham, Volume 5, Part 1, 213.

- ^ Needham, Volume 5, Part 1, 209.

- ^ a b c d Needham, Volume 5, Part 1, 216.

- ^ Needham, Volume 5, Part 1, 217–219.

- ^ Needham, Volume 5, Part 1, 218–219

- ^ a b c d e Needham, Volume 5, Part 1, 219.

- ^ a b Needham, Volume 5, Part 1, 220

Sources

[edit]- Works cited

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 5, Part 1. Taipei: Caves Books Ltd.