Easter Island

Easter Island

| |

|---|---|

Outer slope of the Rano Raraku volcano, the quarry of the Moais with many uncompleted statues. | |

|

| |

| |

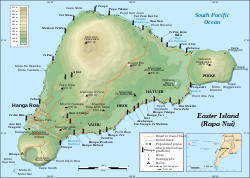

| Coordinates: 27°7′S 109°22′W / 27.117°S 109.367°W | |

| Country | Chile |

| Region | Valparaíso |

| Province | Isla de Pascua |

| Commune | Isla de Pascua |

| Seat | Hanga Roa |

| Government | |

| • Type | Municipality |

| • Body | Municipal council |

| • Provincial Governor | René De la Puente Hey (IND) |

| • Alcalde | Pedro Edmunds Paoa (PRO) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 163.6 km2 (63.2 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 507 m (1,663 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | 0 m (0 ft) |

| Population (2017 census) | |

| • Total | 7,750[1] |

| • Density | 47/km2 (120/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (EAST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (EASST) |

| Country Code | +56 |

| Currency | Peso (CLP) |

| Language | Spanish, Rapa Nui |

| Driving side | right |

| Website | dppisladepascua |

| NGA UFI=-905269 | |

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

Moai at Rano Raraku, Easter Island | |

| Criteria | Cultural: i, iii, v |

| Reference | 715 |

| Inscription | 1995 (19th Session) |

| Area | 71.3 km2 (27.5 sq mi) |

Easter Island (Spanish: Isla de Pascua [ˈisla ðe ˈpaskwa]; Rapa Nui: Rapa Nui) is an island and special territory of Chile in the southeastern Pacific Ocean, at the southeasternmost point of the Polynesian Triangle in Oceania. The island is most famous for its nearly 1,000 extant monumental statues, called moai, which were created by the early Rapa Nui people. In 1995, UNESCO named Easter Island a World Heritage Site, with much of the island protected within Rapa Nui National Park.

Experts disagree on when the island's Polynesian inhabitants first reached the island. While many in the research community cited evidence that they arrived around the year 800, a 2007 study found compelling evidence that they arrived closer to 1200.[3][4] The inhabitants created a thriving and industrious culture, as evidenced by the island's numerous enormous stone moai and other artifacts. But land clearing for cultivation and the introduction of the Polynesian rat led to gradual deforestation.[3] By the time of European arrival in 1722, the island's population was estimated to be 2,000 to 3,000. European diseases, Peruvian slave raiding expeditions in the 1860s, and emigration to other islands such as Tahiti further depleted the population, reducing it to a low of 111 native inhabitants in 1877.[5]

Chile annexed Easter Island in 1888. In 1966, the Rapa Nui were granted Chilean citizenship. In 2007 the island gained the constitutional status of "special territory" (Spanish: territorio especial). Administratively, it belongs to the Valparaíso Region, constituting a single commune (Isla de Pascua) of the Province of Isla de Pascua.[6] The 2017 Chilean census registered 7,750 people on the island, of whom 3,512 (45%) considered themselves Rapa Nui.[7]

Easter Island is one of the world's remotest inhabited islands.[8] The nearest inhabited land (around 50 residents in 2013) is Pitcairn Island, 2,075 kilometres (1,289 mi) away;[9] the nearest town with a population over 500 is Rikitea, on the island of Mangareva, 2,606 km (1,619 mi) away; the nearest continental point lies in central Chile, 3,512 km (2,182 mi) away.

Etymology

The name "Easter Island" was given by the island's first recorded European visitor, the Dutch explorer Jacob Roggeveen, who encountered it on Easter Sunday (5 April), 1722, while searching for "Davis Land".[10] Roggeveen named it Paasch-Eyland (18th-century Dutch for "Easter Island").[11][12] The island's official Spanish name, Isla de Pascua, also means "Easter Island".

The current Polynesian name of the island, Rapa Nui ("Big Rapa"), was coined after the slave raids of the early 1860s, and refers to the island's topographic resemblance to the island of Rapa in the Bass Islands of the Austral Islands group.[13] Norwegian ethnographer Thor Heyerdahl argued that Rapa was Easter Island's original name and that the Bass Islands' Rapa (Rapa Iti) was named by refugees from it.[14]

The phrase Te pito o te henua has been said to be the island's original name since French ethnologist Alphonse Pinart gave it the romantic translation "the Navel of the World" in his Voyage à l'Île de Pâques, published in 1877.[15] William Churchill (1912) inquired about the phrase and was told that there were three te pito o te henua, these being the three capes (land's ends) of the island. The phrase appears to have been used in the same sense as the designation "Land's End" at the tip of Cornwall. He was unable to elicit a Polynesian name for the island and concluded that there may not have been one.[16]

According to Barthel (1974), oral tradition has it that the island was first named Te pito o te kainga a Hau Maka, "The little piece of land of Hau Maka".[17] But there are two words pronounced pito in Rapa Nui, one meaning "end" and one "navel", and the phrase can thus also mean "The Navel of the World". Another name, Mata ki te rangi, means "Eyes looking to the sky".[18]

Islanders are referred to in Spanish as pascuense, but members of the indigenous community are commonly called Rapa Nui.

Felipe González de Ahedo named it Isla de San Carlos ("Saint Charles's Island", the patron saint of Charles III of Spain) or Isla de David (probably the phantom island of Davis Land; sometimes translated as "Davis's Island"[19]) in 1770.[20]

History

Introduction

Oral tradition states the island was first settled by a two-canoe expedition originating from Marae Renga (or Marae Toe Hau—otherwise known as Cook Islands), and led by the chief Hotu Matu'a and his captain Tu'u ko Iho. The island was first scouted after Haumaka dreamed of such a far-off country; Hotu deemed it a worthwhile place to flee from a neighboring chief, one to whom he had already lost three battles. At their time of arrival, the island had one lone settler, Nga Tavake 'a Te Rona. After a brief stay at Anakena, the colonists settled in different parts of the island. Hotu's heir, Tu'u ma Heke, was born on the island. Tu'u ko Iho is viewed as the leader who brought the statues and caused them to walk.[21]

The Easter Islanders are considered Southeast Polynesians. Similar sacred zones with statuary (marae and ahu) in East Polynesia demonstrate homology with most of Eastern Polynesia. At contact, populations were about 3,000–4,000.[21]: 17–18, 20–21, 31, 41–45

By the 15th century, two confederations, hanau, of social groupings, mata, existed, based on lineage. The western and northern portion of the island belonged to the Tu'u, which included the royal Miru, with the royal center at Anakena, though Tahai and Te Peu served as earlier capitals. The eastern part of the island belonged to the 'Otu 'Itu. Shortly after the Dutch visit, from 1724 until 1750, the 'Otu 'Itu fought the Tu'u for control of the island. This continued until the 1860s. Famine followed the burning of huts and the destruction of fields. Social control vanished as the ordered way of life gave way to lawlessness and predatory bands as the warrior class took over. Homelessness prevailed, with many living underground. After the Spanish visit, from 1770 onward, a period of statue toppling, huri mo'ai, commenced. This was an attempt by competing groups to destroy the socio-spiritual power, or mana, represented by statues, making sure to break them in the fall to ensure they were dead and without power. None were left standing by the time of the arrival of the French missionaries in the 1860s.[21]: 21–24, 27, 54–56, 64–65

Between 1862 and 1888, about 94% of the population perished or emigrated. The island was victimized by blackbirding from 1862 to 1863, resulting in the abduction or killing of about 1,500, with 1,408 working as indentured servants in Peru. Only about a dozen eventually returned to Easter Island, but they brought smallpox, which decimated the remaining population of 1,500. Those who perished included the island's tumu ivi 'atua, bearers of the island's culture, history, and genealogy besides the rongorongo experts.[21]: 86–91

Rapa Nui settlement

Estimated dates of initial settlement of Easter Island have ranged from 400 to 1300 CE.[22] though the current best estimate for colonization is in the 12th century CE.[23] Easter Island colonization likely coincided with the arrival of the first settlers in Hawaii. Rectifications in radiocarbon dating have changed almost all of the previously posited early settlement dates in Polynesia. Ongoing archaeological studies provide this late date: "Radiocarbon dates for the earliest stratigraphic layers at Anakena, Easter Island, and analysis of previous radiocarbon dates imply that the island was colonized late, about 1200 CE. Significant ecological impacts and major cultural investments in monumental architecture and statuary thus began soon after initial settlement."[24][25]

According to oral tradition, the first settlement was at Anakena. Researchers have noted that the Caleta Anakena landing point provides the island's best shelter from prevailing swells as well as a sandy beach for canoe landings and launchings, so it is a likely early place of settlement. However, radiocarbon dating concludes that other sites preceded Anakena by many years, especially the Tahai by several centuries.

The island was populated by Polynesians who most likely navigated in canoes or catamarans from the Gambier Islands (Mangareva, 2,600 km (1,600 mi) away) or the Marquesas Islands, 3,200 km (2,000 mi) away. According to some theories, such as the Polynesian Diaspora Theory, there is a possibility that early Polynesian settlers arrived from South America due to their remarkable sea-navigation abilities. Theorists have supported this through the agricultural evidence of the sweet potato. The sweet potato was a favoured crop in Polynesian society for generations but it originated in South America, suggesting interaction between these two geographic areas.[26] However, recent research suggests that sweet potatoes may have spread to Polynesia by long-distance dispersal long before the Polynesians arrived.[27] When James Cook visited the island, one of his crew members, a Polynesian from Bora Bora, Hitihiti, was able to communicate with the Rapa Nui.[28]: 296–297 It has been noted that the early jumping-off points for the early Polynesian colonization of Easter Island are more likely to have been from Mangareva, Pitcairn and Henderson, which lie about halfway between the Marquesas and Easter.[29] It has been observed that there is great similarity with the Rapa Nui language and Early Mangarevan,[29] similarities between a statue found in Pitcairn and some statues found in Easter Island,[29] the resemblance of tool styles in Easter Island to those in Mangareva and Pitcairn,[29] and correspondences of skulls found in Easter Island to two skulls found in Henderson,[29] all suggesting Henderson and Pitcairn Islands to have been early stepping stones from Mangareva to Easter Island,[29] which in 1999, a voyage with reconstructed Polynesian boats was able to reach Easter Island from Mangareva after a seventeen-and-a-half-day voyage.[29][30]

According to oral traditions recorded by missionaries in the 1860s, the island originally had a strong class system: an ariki, or high chief, wielded great power over nine other clans and their respective chiefs. The high chief was the eldest descendant through first-born lines of the island's legendary founder, Hotu Matu'a. The most visible element in the culture was the production of massive moai statues that some believe represented deified ancestors. According to National Geographic, "Most scholars suspect that the moai were created to honor ancestors, chiefs, or other important personages, However, no written and little oral history exists on the island, so it's impossible to be certain."[32]

It was believed that the living had a symbiotic relationship with the dead in which the dead provided everything that the living needed (health, fertility of land and animals, fortune etc.) and the living, through offerings, provided the dead with a better place in the spirit world. Most settlements were located on the coast, and most moai were erected along the coastline, watching over their descendants in the settlements before them, with their backs toward the spirit world in the sea.

Ecocide hypothesis

In his book Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed, Jared Diamond suggested that cannibalism took place on Easter Island after the construction of the moai contributed to environmental degradation when extreme deforestation (ecocide) destabilized an already precarious ecosystem.[33] Archeological record shows that at the time of the initial settlement the island was home to many species of trees, including at least three species which grew up to 15 metres (49 ft) or more: Paschalococos (possibly the largest palm trees in the world at the time), Alphitonia zizyphoides, and Elaeocarpus rarotongensis. At least six species of land birds were known to live on the island. A major factor that contributed to the extinction of multiple plant species was the introduction of the Polynesian rat. Studies by paleobotanists have shown rats can dramatically affect the reproduction of vegetation in an ecosystem. In the case of Rapa Nui, recovered plant seed shells showed markings of being gnawed on by rats.[3] This version of the history speculates a high former population to the island that had already declined before Europeans arrived. Barbara A. West wrote, "Sometime before the arrival of Europeans on Easter Island, the Rapanui experienced a tremendous upheaval in their social system brought about by a change in their island's ecology... By the time of European arrival in 1722, the island's population had dropped to 2,000–3,000 from a high of approximately 15,000 just a century earlier."[34]

By that time, 21 species of trees and all species of land birds became extinct through some combination of over-harvesting, over-hunting, rat predation, and climate change. The island was largely deforested, and it did not have any trees taller than 3 m (9.8 ft). Loss of large trees meant that residents were no longer able to build seaworthy vessels, significantly diminishing their fishing abilities. According to this version of the history, the trees were used as rollers to move the statues to their place of erection from the quarry at Rano Raraku.[35] Deforestation also caused erosion which caused a sharp decline in agricultural production.[3] This was exacerbated by the loss of land birds and the collapse in seabird populations as a source of food. By the 18th century, islanders were largely sustained by farming, with domestic chickens as the primary source of protein.[36]

As the island became overpopulated and resources diminished, warriors known as matatoa gained more power and the Ancestor Cult ended, making way for the Bird Man Cult. Beverly Haun wrote, "The concept of mana (power) invested in hereditary leaders was recast into the person of the birdman, apparently beginning circa 1540, and coinciding with the final vestiges of the moai period."[37] This cult maintained that, although the ancestors still provided for their descendants, the medium through which the living could contact the dead was no longer statues but human beings chosen through a competition. The god responsible for creating humans, Makemake, played an important role in this process. Katherine Routledge, who systematically collected the island's traditions in her 1919 expedition,[38] showed that the competitions for Bird Man (Rapa Nui: tangata manu) started around 1760, after the arrival of the first Europeans, and ended in 1878, with the construction of the first church by Roman Catholic missionaries who formally arrived in 1864. Petroglyphs representing Bird Men on Easter Island are the same as some in Hawaii, indicating that this concept was probably brought by the original settlers; only the competition itself was unique to Easter Island. According to Diamond and Heyerdahl's version of the island's history, the huri mo'ai – "statue-toppling" – continued into the 1830s as a part of fierce internal wars. By 1838, the only standing moai were on the slopes of Rano Raraku, in Hoa Hakananai'a in Orongo, and Ariki Paro in Ahu Te Pito Kura.

Criticism of the ecocide hypothesis

Diamond and West's version of the history is highly controversial. A study headed by Douglas Owsley published in 1994 asserted that there is little archaeological evidence of pre-European societal collapse. Bone pathology and osteometric data from islanders of that period clearly suggest few fatalities can be attributed directly to violence.[39] Research by Binghamton University anthropologists Robert DiNapoli and Carl Lipo in 2021 suggests that the island experienced steady population growth from its initial settlement until European contact in 1722. The island never had more than a few thousand people prior to European contact, and their numbers were increasing rather than dwindling.[40][41]

Several works that address or counter Diamond's claims in Collapse have been published. In Ecological Catastrophe and Collapse -The Myth of "Ecocide" on Rapa Nui (Easter Island), Hunt and Lipo set out a claim-by-claim rebuttal to Diamond's claims. This includes, among other things, that deforestation began immediately, but the population grew while the forest declined as the land was converted to more productive farmland; that the island's population grew continuously up to the arrival of Europeans, with the only clear decline starting in the period of 1750–1800; that studies from other islands show clearly that Polynesian settlement without Polynesian rats is only associated with minimal forest loss while the arrival of rats without human settlement is devastating to forest populations; only species favoured by the rats for consumption were lost, not for example the native Sophora toromiro; that the island's drier, less predictable climate made it inherently more vulnerable to deforestation than other Polynesian islands; and that the population declines on Rapa Nui can be well attributed to the very mechanism described by Diamond in another of his books, Guns, Germs and Steel - the devastating impact of introduced diseases, raids, slavery, and exploitation on indigenous populations.[42]

In another work, Hunt and Lipo discuss more evidence against the ecocide hypothesis. In addition to focusing on the settlement chronology, they note that the island has an abnormally low amount of evidence of warfare compared to other Polynesian islands, only relatively small-scale intergroup conflict. There are no fortifications, and the attributed obsidian mata'a "weapons" show rather evidence of having been used in agriculture, and indeed, match up with agricultural tools long recognized among artifacts of other Polynesian peoples.[43] Evidence of violence among skeletal remains of pre-European native skeletons is minimal, with only 2.5% of crania showing evidence of antemortem fractures,[43] consistent with Oswley's conclusions: "most skeletal injuries appear to have been nonlethal. Few fatalities were directly attributable to violence. The physical evidence suggests that the frequency of warfare and lethal events was exaggerated in folklore."[44] Despite known folklore, Hunt and Lipo also conclude that clear evidence of cannibalism among skeletal remains is entirely lacking.[43] They note that in the search for evidence supporting ecocide, the far more obvious answer has long been known, and cite Metraux as evidence that "The historic slave-trading, epidemic disease, intensive sheep ranching, and tragic population collapse - indeed the genocide of the Rapanui People - is well documented, and has been recognized for a long time."[45] They conclude that when it comes to the science, "It does not matter whether Rapa Nui offers a parable for today's urgent environmental problems."[43]

In a 2010 metastudy on the state of the evidence, the Mulrooney et al. concludes that "To date, there is no conclusive evidence for the proposed precontact collapse of Rapa Nui society". In particular, the authors note that the obsidian usage trends lead to entirely different, self-inconsistent interpretations, while use of the oral histories of widespread intertribal warfare is undercut not just by early foreign visitors referring to the people as peaceful and docile, but the fact that the very wars in question were referred to as the wars of the throwing down of the statues, an event well-dated to not have begun until after western contact.[46]

European contact

The first recorded European contact with the island was on 5 April 1722, Easter Sunday, by Dutch navigator Jacob Roggeveen.[28] His visit resulted in the death of about a dozen islanders, including the tumu ivi 'atua, and the wounding of many others.[21]: 46–53

The next foreign visitors (on 15 November 1770) were two Spanish ships, San Lorenzo and Santa Rosalia, under the command of Captain Don Felipe Gonzalez de Ahedo.[28]: 238, 504 The Spanish were amazed by the "standing idols", all of which were erect at the time.[21]: 60–64

In 1776 the Chilean priest Juan Ignacio Molina highlights the island for its "monumental statues" in the fifth chapter on "Chilean Islands" of his book "Natural and Civil History of the Kingdom of Chile".[47]

Four years later, in 1774, British explorer James Cook visited Easter Island; he reported that some statues had been toppled. Through the interpretation of Hitihiti, Cook learned the statues commemorated their former high chiefs, including their names and ranks.[28]: 296–297

On 10 April 1786, French Admiral Jean-François de Galaup, comte de Lapérouse anchored at Hanga Roa at the start of a circumnavigation of the Pacific. He made a detailed map of the bay, including his anchorage points, as well as a more generalised map of the island, plus some illustrations.[48]

19th century

A series of devastating events killed or removed most of the population in the 1860s. In December 1862, Peruvian slave raiders struck. Violent abductions continued for several months, eventually capturing around 1,500 men and women, half of the island's population.[49] Among those captured were the island's paramount chief, his heir, and those who knew how to read and write the rongorongo script, the only Polynesian script to have been found to date, although debate exists about whether this is proto-writing or true writing.

When the slave raiders were forced to repatriate the people they had kidnapped, carriers of smallpox disembarked together with a few survivors on each of the islands.[50] This created devastating epidemics from Easter Island to the Marquesas islands. Easter Island's population was reduced to the point where some of the dead were not even buried.[21]: 91

The first Christian missionary, Eugène Eyraud, arrived in January 1864 and spent most of that year on the island and reported for the first time the existence of the so-called rongo-rongo tablets; but mass conversion of the Rapa Nui only came after his return in 1866 with Father Hippolyte Roussel. Two other missionaries arrived with Captain Jean-Baptiste Dutrou-Bornier. Eyraud contracted tuberculosis during the 1867 island epidemic, which took a quarter of the island's remaining population of 1,200, with only 930 Rapanui remaining. The dead included the last ariki mau, the last East Polynesia royal first-born son, the 13-year-old Manu Rangi. Eyraud died of tuberculosis in August 1868, by which time almost the entire Rapa Nui population had become Roman Catholic.[21]: 92–103

Tuberculosis, introduced by whalers in the mid-19th century, had already killed several islanders when Eugène Eyraud, died from this disease in 1867. It ultimately killed approximately a quarter of the island's population. In the following years, the managers of the sheep ranch and the missionaries started buying the newly available lands of the deceased, and this led to great confrontations between natives and settlers.

Jean-Baptiste Dutrou-Bornier bought up all of the island apart from the missionaries' area around Hanga Roa and moved a few hundred Rapa Nui to Tahiti to work for his backers. In 1871 the missionaries, having fallen out with Dutrou-Bornier, evacuated all but 171 Rapa Nui to the Gambier islands.[51] Those who remained were mostly older men. Six years later, only 111 people lived on Easter Island, and only 36 of them had any offspring.[52] From that point on, the island's population slowly recovered. But with over 97% of the population dead or gone in less than a decade, much of the island's cultural knowledge had been lost.

Alexander Salmon, Jr., the son of an English Jewish merchant and a Pōmare Dynasty princess, eventually worked to repatriate workers from his inherited copra plantation. He eventually bought up all lands on the island with the exception of the mission, and was its sole employer. He worked to develop tourism on the island and was the principal informant for the British and German archaeological expeditions for the island. He sent several pieces of genuine Rongorongo to his niece's husband, the German consul in Valparaíso, Chile. Salmon sold the Brander Easter Island holdings to the Chilean government on 2 January 1888, and signed as a witness to the cession of the island. He returned to Tahiti in December 1888. He effectively ruled the island from 1878 until his cession to Chile in 1888.

In 1887 Chile took concrete actions to incorporate the island into the national territory, at the request of the Chilean Navy Captain Policarpo Toro, who was concerned about the unprotected situation of the Rapa Nui for decades and began to influence the situation on his own initiative. Policarpo, through negotiations, bought land on the island at the request of the Bishop of Valparaiso, Salvador Donoso Rodriguez, owner of 600 hectares, together with the Salmon brothers, Dutrou-Bornier and John Brander, from Tahiti. The Chilean captain put money from his own pocket for this purpose, together with 6000 pounds sterling sent by the Chilean government.[47] According to Rapa Nui tradition, the lands could not be sold, however, third parties believed they owned them and they were bought from them so that they would not interfere in the affairs of the island from that moment on.

At that time, the Rapa Nui population reached alarming numbers. In a census carried out by the Chilean corvette Abtao in 1892, there were only 101 Rapa Nui alive, of which only 12 were adult men. The Rapa Nui ethnic group, along with their culture, was at its closest point to extinction.[47]

Then, on September 9, 1888, thanks to the efforts of the Bishop of Tahiti, Monsignor José María Verdier, the Agreement of Wills (Acuerdo de Voluntades) was signed, in which the local representative Atamu Tekena, head of the Council of Rapanui Chiefs ceded the sovereignty of the island to the State of Chile, represented by Policarpo Toro. The Rapa Nui elders ceded sovereignty, without renouncing their titles as chiefs, the ownership of their lands, the validity of their culture and traditions and on equal terms. The Rapa Nui sold nothing, they were integrated in equal conditions to Chile.

The annexation to Chile, together with the abolition of slavery in Peru, brought the advantage that foreign slavers did not take any more inhabitants from the island. However, in 1895, the Compañía Explotadora de Isla de Pascua from Enrique Merlet obtained the concession of the entire island after the failure of the State's colonization plan following the Civil War of 1891 and the change of government in the country.

The company imposed prohibitions to live and work outside Hanga Roa and even forced labor of the islanders in the company, something that was avoided thanks to the "safe-conducts" given by the Navy that allowed the islanders to cross the entire island once the Navy took control of the island during the 20th Century.[53]

In 1903 the island was bought by the English sheep-farming company Williamson Balfor from the Merlet company, and – no longer being able to farm for food – the natives were forced to work on the ranches in order to buy food.[54]

20th century

In 1914 there was an uprising of the natives inspired by the elderly catechist María Angata Veri Veri and led by Daniel Maria Teave with the aim of getting the State to take charge of the situation generated by the company. The Navy held the company responsible for the "brutal and savage acts" committed by Merlet and the company's administrators and an investigation was requested.

In 1916, the island was declared a subdelegation of the Department of Valparaíso. In the same year, Archbishop Rafael Edwards Salas visited the island and became the main spokesman for the natives' complaints and demands. However, the Chilean State decided to renew the lease to the company, under the figure of the so-called "Provisional Temperament", distributing additional lands to the natives (5 ha per marriage as of 1926), allocating lands for the Chilean administration and establishing the permanent presence of the Navy, which in 1936 established a regulation according to which, with prior permission, the natives could leave Hanga Roa to fish or provide themselves with fuel.[53][55]

Monsignor Rafael Edwards sought to have the island declared a "naval jurisdiction" in order to intervene in it as military vicar and in this way support the Rapa Nui community, creating better living conditions.[53]

In 1933, the Chilean State Defense Council required the registration of the island in the name of the State in order to protect it from private individuals who wanted to register it in their own name.[53]

Until the 1960s the Rapanui were confined to Hanga Roa. The rest of the island was rented to the Williamson-Balfour Company as a sheep farm until 1953 when President Carlos Ibáñez del Campo cancelled the company's contract for non-compliance and then assigned the entire administration of the island to the Chilean Navy.[56] The island was then managed by the Chilean Navy until 1966, at which point the island was reopened in its entirety. The Rapanui were given Chilean citizenship that year with the Pascua Law enacted during the government of Eduardo Frei Montalva.[57]: 112 Only Spanish was taught in the schools until that year. The Law also created the Isla de Pascua commune depending from the Valparaíso Province and implemented the Civil Registry, created the positions of governor, mayor and councilman, as well as the 6th Police Station of Carabineros de Chile, the first fire company of Easter Island, schools and a hospital. The first mayor was sworn in 1966 and was Alfonso Rapu who sent a letter to President Frei two years prior influencing him to create the Pascua Law.

Islanders were only able to travel off the island easily after the construction of the Mataveri International Airport in 1965, which was built by the Longhi construction company, carrying hundreds of workers, heavy machinery, tents and a field hospital on ships. However, its use did not go beyond airline operations with small groups of tourists. At the same time, a NASA tracking station operated on the island, which ceased operations in 1975.

Between 1965 and 1970, the United States Air Force (USAF) settled on Easter Island, radically changing the way of life of the Rapa Nui, as they became acquainted with the customs of the consumer societies of the developed world.[58][59]

In April 1967 LAN Chile flights began to land and the island began to be oriented towards cultural tourism. Since then, the main concerns for the natives were to strengthen production and marketing cooperatives, which received state support, and to recover their communal lands.

Following the 1973 Chilean coup d'état that brought Augusto Pinochet to power, Easter Island was placed under martial law. Tourism slowed down and private property was restored. During his time in power, Pinochet visited Easter Island on three occasions. The military built a number of new military facilities and a new city hall.[60]

On January 24, 1975, television arrived on the island, with the inauguration of a station of Televisión Nacional de Chile, which broadcast programming on a delayed basis until 1996, when live satellite transmissions to the island began.

In 1976 the Isla de Pascua Province was created with Arnt Arentsen Pettersen appointed as the first governor between 1976 and 1979. Between 1984 and 1990 the administration of Governor Sergio Rapu Haoa stands out and since then all the governors have been Rapanui.

In 1979, Decree Law No. 2885 was enacted to grant individual land titles to regular holders.

On April 1, 1986, Law No. 18,502 is enacted, which establishes the special fuel subsidy in Easter Island, stating that it "may not exceed in each product 3.5 monthly tax units per cubic meter, whose value may be paid directly or through the imputation of the respective amount to the payment of certain taxes".

As a result of an agreement in 1985 between Chile and the United States, the runway at Mataveri International Airport was extended by 423 metres (1,388 ft), reaching 3,353 metres (11,001 ft), and was re-opened in 1987. Pinochet is reported to have refused to attend the opening ceremony in protest against pressures from the United States to address human rights cases.[61]

21st century

Fishers of Rapa Nui have shown their concern of illegal fishing on the island. "Since the year 2000 we started to lose tuna, which is the basis of the fishing on the island, so then we began to take the fish from the shore to feed our families, but in less than two years we depleted all of it", Pakarati said.[62] On 30 July 2007, a constitutional reform gave Easter Island and the Juan Fernández Islands (also known as Robinson Crusoe Island) the status of "special territories" of Chile. Pending the enactment of a special charter, the island continues to be governed as a province of the V Region of Valparaíso.[63]

Species of fish were collected in Easter Island for one month in different habitats including shallow lava pools and deep waters. Within these habitats, two holotypes and paratypes, Antennarius randalli and Antennarius moai, were discovered. These are considered frog-fish because of their characteristics: "12 dorsal rays, last two or three branched; bony part of first dorsal spine slightly shorter than second dorsal spine; body without bold zebra-like markings; caudal peduncle short, but distinct; last pelvic ray divided; pectoral rays 11 or 12".[64]

In 2018, the government decided to limit the stay period for tourists from 90 to 30 days because of social and environmental issues faced by the Island to preserve its historical importance.[65]

A tsunami warning was declared for Easter Island after the 2022 Hunga Tonga–Hunga Ha'apai eruption and tsunami.[66]

Easter Island was closed to tourists from March 17, 2020, until August 4, 2022, due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[67] Then in early October 2022, just two months after the island was reopened to tourists, a forest fire burned nearly 148 acres (60 hectares) of the island, causing irreparable damage to some of the moai.[68] Arson is suspected.[69]

Indigenous rights movement

Starting in August 2010, members of the indigenous Hitorangi clan occupied the Hangaroa Eco Village and Spa.[70][71] The occupiers allege that the hotel was bought from the Pinochet government, in violation of a Chilean agreement with the indigenous Rapa Nui, in the 1990s.[72] The occupiers say their ancestors had been cheated into giving up the land.[73] According to a BBC report, on 3 December 2010, at least 25 people were injured when Chilean police using pellet guns attempted to evict from these buildings a group of Rapa Nui who had claimed that the land the buildings stood on had been illegally taken from their ancestors.[74] In 2020 the conflict was settled. The property rights were transferred to the Hitorangi clan while the owners retained the exploitation of the hotel for 15 years.[75]

In January 2011, the UN Special Rapporteur on Indigenous People, James Anaya, expressed concern about the treatment of the indigenous Rapa Nui by the Chilean government, urging Chile to "make every effort to conduct a dialogue in good faith with representatives of the Rapa Nui people to solve, as soon as possible the real underlying problems that explain the current situation".[70] The incident ended in February 2011, when up to 50 armed police broke into the hotel to remove the final five occupiers. They were arrested by the government, and no injuries were reported.[70]

Geography

Easter Island is one of the world's most isolated inhabited islands.[76] Its closest inhabited neighbour is Pitcairn Island, 1,931 km (1,200 mi) to the west, with approximately 50 inhabitants.[77] The nearest continental point lies in central Chile near Concepción, at 3,512 kilometres (2,182 mi). Easter Island's latitude is similar to that of Caldera, Chile, and it lies 3,510 km (2,180 mi) west of continental Chile at its nearest point (between Lota and Lebu in the Biobío Region). Isla Salas y Gómez, 415 km (258 mi) to the east, is closer but is uninhabited. The Tristan da Cunha archipelago in the southern Atlantic competes for the title of the most remote island, lying 2,430 km (1,510 mi) from Saint Helena island and 2,816 km (1,750 mi) from the South African coast.

The island is about 24.6 km (15.3 mi) long by 12.3 km (7.6 mi) at its widest point; its overall shape is triangular. It has an area of 163.6 km2 (63.2 sq mi), and a maximum elevation of 507 m (1,663 ft) above mean sea level. There are three Rano (freshwater crater lakes), at Rano Kau, Rano Raraku and Rano Aroi, near the summit of Terevaka, but no permanent streams or rivers.

Geology

Easter Island is a volcanic island, consisting mainly of three extinct coalesced volcanoes: Terevaka (altitude 507 metres) forms the bulk of the island, while two other volcanoes, Poike and Rano Kau, form the eastern and southern headlands and give the island its roughly triangular shape. Lesser cones and other volcanic features include the crater Rano Raraku, the cinder cone Puna Pau and many volcanic caves including lava tubes.[78] Poike used to be a separate island until volcanic material from Terevaka united it to the larger whole. The island is dominated by hawaiite and basalt flows which are rich in iron and show affinity with igneous rocks found in the Galápagos Islands.[79]

Easter Island and surrounding islets, such as Motu Nui and Motu Iti, form the summit of a large volcanic mountain rising over 2,000 m (6,600 ft) from the sea bed. The mountain is part of the Salas y Gómez Ridge, a (mostly submarine) mountain range with dozens of seamounts, formed by the Easter hotspot. The range begins with Pukao and next Moai, two seamounts to the west of Easter Island, and extends 2,700 km (1,700 mi) east to the Nazca Ridge. The ridge was formed by the Nazca Plate moving over the Easter hotspot.[81]

Located about 350 km (220 mi) east of the East Pacific Rise, Easter Island lies within the Nazca Plate, bordering the Easter Microplate. The Nazca-Pacific relative plate movement due to the seafloor spreading, amounts to about 150 mm (5.9 in) per year. This movement over the Easter hotspot has resulted in the Easter Seamount Chain, which merges into the Nazca Ridge further to the east. Easter Island and Isla Salas y Gómez are surface representations of that chain. The chain has progressively younger ages to the west. The current hotspot location is speculated to be west of Easter Island, amidst the Ahu, Umu and Tupa submarine volcanic fields and the Pukao and Moai seamounts.[82]

Easter Island lies atop the Rano Kau Ridge, and consists of three shield volcanoes with parallel geologic histories. Poike and Rano Kau exist on the east and south slopes of Terevaka, respectively. Rano Kau developed between 0.78 and 0.46 Ma from tholeiitic to alkalic basalts. This volcano possesses a clearly defined summit caldera. Benmoreitic lavas extruded about the rim from 0.35 to 0.34 Ma. Finally, between 0.24 and 0.11 Ma, a 6.5 km (4.0 mi) fissure developed along a NE–SW trend, forming monogenetic vents and rhyolitic intrusions. These include the cryptodome islets of Motu Nui and Motu Iti, the islet of Motu Kao Kao, the sheet intrusion of Te Kari Kari, the perlitic obsidian Te Manavai dome and the Maunga Orito dome.[82]

Poike formed from tholeiitic to alkali basalts from 0.78 to 0.41 Ma. Its summit collapsed into a caldera which was subsequently filled by the Puakatiki lava cone pahoehoe flows at 0.36 Ma. Finally, the trachytic lava domes of Maunga Vai a Heva, Maunga Tea Tea, and Maunga Parehe formed along a NE-SW trending fissure.[82]

Terevaka formed around 0.77 Ma of tholeiitic to alkali basalts, followed by the collapse of its summit into a caldera. Then at about 0.3Ma, cinder cones formed along a NNE-SSW trend on the western rim, while porphyritic benmoreitic lava filled the caldera, and pahoehoe flowed towards the northern coast, forming lava tubes, and to the southeast. Lava domes and a vent complex formed in the Maunga Puka area, while breccias formed along the vents on the western portion of Rano Aroi crater. This volcano's southern and southeastern flanks are composed of younger flows consisting of basalt, alkali basalt, hawaiite, mugearite, and benmoreite from eruptive fissures starting at 0.24 Ma. The youngest lava flow, Roiho, is dated at 0.11 Ma. The Hanga O Teo embayment is interpreted to be a 200 m high landslide scarp.[82]

Rano Raraku and Maunga Toa Toa are isolated tuff cones of about 0.21 Ma. The crater of Rano Raraku contains a freshwater lake. The stratified tuff is composed of sideromelane, slightly altered to palagonite, and somewhat lithified. The tuff contains lithic fragments of older lava flows. The northwest sector of Rano Raraku contains reddish volcanic ash.[82] According to Bandy, "...all of the great images of Easter Island are carved from" the light and porous tuff from Rano Raraku. A carving was abandoned when a large, dense and hard lithic fragment was encountered. However, these lithics became the basis for stone hammers and chisels. The Puna Pau crater contains an extremely porous pumice, from which was carved the Pukao "hats". The Maunga Orito obsidian was used to make the "mataa" spearheads.[83]

In the first half of the 20th century, steam reportedly came out of the Rano Kau crater wall. This was photographed by the island's manager, Mr. Edmunds.[84]

The ancient Easter Island residents captured fresh groundwater where it seeped into the sea.[85][86][87][88][89]

Climate

Under the Köppen climate classification, the climate of Easter Island is classified as a tropical rainforest climate (Af) that borders on a humid subtropical climate (Cfa).[90] The lowest temperatures are recorded in July and August (minimum 15 °C or 59 °F) and the highest in February (maximum temperature 28 °C or 82.4 °F[91]), the summer season in the southern hemisphere. Winters are relatively mild. The rainiest month is May, though the island experiences year-round rainfall.[92] Easter Island's isolated location exposes it to winds which help to keep the temperature fairly cool. Precipitation averages 1,118 millimetres or 44 inches per year. Occasionally, heavy rainfall and rainstorms strike the island. These occur mostly in the winter months (June–August). Since it is close to the South Pacific High and outside the range of the intertropical convergence zone, cyclones and hurricanes do not occur around Easter Island.[93] There is significant temperature moderation due to its isolated position in the middle of the ocean.

| Climate data for Easter Island (Mataveri International Airport) 1991–2020, extremes 1912–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 32.0 (89.6) |

31.0 (87.8) |

32.0 (89.6) |

31.0 (87.8) |

30.0 (86.0) |

29.0 (84.2) |

31.0 (87.8) |

28.3 (82.9) |

30.0 (86.0) |

29.0 (84.2) |

33.0 (91.4) |

34.0 (93.2) |

34.0 (93.2) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 26.9 (80.4) |

27.5 (81.5) |

26.9 (80.4) |

25.5 (77.9) |

23.4 (74.1) |

21.9 (71.4) |

21.3 (70.3) |

21.2 (70.2) |

21.5 (70.7) |

22.5 (72.5) |

23.8 (74.8) |

25.5 (77.9) |

24.0 (75.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 23.5 (74.3) |

24.0 (75.2) |

23.6 (74.5) |

22.4 (72.3) |

20.5 (68.9) |

19.3 (66.7) |

18.6 (65.5) |

18.5 (65.3) |

18.7 (65.7) |

19.3 (66.7) |

20.6 (69.1) |

22.1 (71.8) |

20.9 (69.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 20.0 (68.0) |

20.6 (69.1) |

20.2 (68.4) |

19.4 (66.9) |

17.7 (63.9) |

16.7 (62.1) |

15.9 (60.6) |

15.7 (60.3) |

15.8 (60.4) |

16.2 (61.2) |

17.5 (63.5) |

18.7 (65.7) |

17.9 (64.2) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 12.0 (53.6) |

14.0 (57.2) |

8.2 (46.8) |

12.2 (54.0) |

10.0 (50.0) |

6.1 (43.0) |

7.2 (45.0) |

7.0 (44.6) |

8.0 (46.4) |

8.0 (46.4) |

8.0 (46.4) |

9.7 (49.5) |

6.1 (43.0) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 81.3 (3.20) |

69.3 (2.73) |

86.9 (3.42) |

123.0 (4.84) |

116.9 (4.60) |

109.2 (4.30) |

113.1 (4.45) |

97.1 (3.82) |

97.3 (3.83) |

90.9 (3.58) |

75.2 (2.96) |

69.6 (2.74) |

1,129.8 (44.48) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 10.1 | 9.6 | 10.7 | 11.6 | 12.0 | 12.3 | 11.6 | 10.6 | 10.2 | 9.3 | 9.4 | 9.0 | 126.4 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 77 | 79 | 79 | 81 | 81 | 81 | 80 | 80 | 79 | 77 | 77 | 78 | 79 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 271.7 | 255.6 | 238.7 | 199.9 | 175.9 | 148.3 | 162.4 | 177.2 | 180.3 | 213.6 | 219.9 | 251.0 | 2,494.5 |

| Source 1: Dirección Meteorológica de Chile (extremes 1954–present)[94][95] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: NOAA (precipitation days 1991–2020),[96] Deutscher Wetterdienst (extremes 1912–1990 and humidity)[97] | |||||||||||||

Ecology

Easter Island, together with its closest neighbour, the tiny island of Isla Salas y Gómez 415 km (258 mi) farther east, is recognized by ecologists as a distinct ecoregion, the Rapa Nui tropical broadleaf forests.[90] The original tropical moist broadleaf forests are now gone, but paleobotanical studies of fossil pollen, tree moulds left by lava flows, and root casts found in local soils indicate that the island was formerly forested, with a range of trees, shrubs, ferns, and grasses. A large extinct palm, Paschalococos disperta, related to the Chilean wine palm (Jubaea chilensis), was one of the dominant trees as attested by fossil evidence. Like its Chilean counterpart it probably took close to 100 years to reach adult height. The Polynesian rat, which the original settlers brought with them, played a very important role in the disappearance of the Rapa Nui palm. Although some may believe that rats played a major role in the degradation of the forest, less than 10% of palm nuts show teeth marks from rats. The remains of palm stumps in different places indicate that humans caused the trees to fall because in large areas, the stumps were cut efficiently.[98]

The loss the palms to make the settlements led to their extinction almost 350 years ago.[99] The toromiro tree (Sophora toromiro) was prehistorically present on Easter Island, but is now extinct in the wild. However, the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew and the Göteborg Botanical Garden are jointly leading a scientific program to reintroduce the toromiro to Easter Island. With the palm and the toromiro virtually gone, there was considerably less rainfall as a result of less condensation. After the island was used to feed thousands of sheep for almost a century, by the mid-1900s the island was mostly covered in grassland with nga'atu or bulrush (Schoenoplectus californicus tatora) in the crater lakes of Rano Raraku and Rano Kau. The presence of these reeds, which are called totora in the Andes, was used to support the argument of a South American origin of the statue builders, but pollen analysis of lake sediments shows these reeds have grown on the island for over 30,000 years.[citation needed] Before the arrival of humans, Easter Island had vast seabird colonies containing probably over 30 resident species, perhaps the world's richest.[100] Such colonies are no longer found on the main island. Fossil evidence indicates six species of land birds (two rails, two parrots, one owl, and one heron), all of which have become extinct.[101] Five introduced species of land bird are known to have breeding populations (see List of birds of Easter Island).

Lack of studies results in poor understanding of the oceanic fauna of Easter Island and waters in its vicinity; however, possibilities of undiscovered breeding grounds for humpback, southern blue and pygmy blue whales including Easter Island and Isla Salas y Gómez have been considered.[102] Potential breeding areas for fin whales have been detected off northeast of the island as well.[103]

- Vegetation on the island

-

Satellite view of Easter Island 2019. The Poike peninsula is on the right.

-

Digital recreation of its ancient landscape, with tropical forest and palm trees

-

Hanga Roa seen from Terevaka, the highest point of the island

-

View of Rano Kau and Pacific Ocean

The immunosuppressant drug sirolimus was first discovered in the bacterium Streptomyces hygroscopicus in a soil sample from Easter Island. The drug is also known as rapamycin, after Rapa Nui.[104] It is now being studied for extending longevity in mice.[105]

Trees are sparse, rarely forming natural groves, and it has been argued whether native Easter Islanders deforested the island in the process of erecting their statues,[106] and in providing sustenance for an overconsumption of natural resources from a overcrowded island.[citation needed] Experimental archaeology demonstrated that some statues certainly could have been placed on Y-shaped wooden frames called miro manga erua and then pulled to their final destinations on ceremonial sites.[106] Other theories involve the use of "ladders" (parallel wooden rails) over which the statues could have been dragged.[107] Rapa Nui traditions metaphorically refer to spiritual power (mana) as the means by which the moai were "walked" from the quarry. Recent experimental recreations have proven that it is fully possible that the moai were literally walked from their quarries to their final positions by use of ropes, casting doubt on the role that their existence plays in the environmental collapse of the island.[108]

Given the island's southern latitude, the climatic effects of the Little Ice Age (about 1650 to 1850) may have exacerbated deforestation, although this remains speculative.[106] Many researchers[109] point to the climatic downtrend caused by the Little Ice Age as a contributing factor to resource stress and to the palm tree's disappearance. Experts, however, do not agree on when the island's palms became extinct.

Jared Diamond dismisses past climate change as a dominant cause of the island's deforestation in his book Collapse which assesses the collapse of the ancient Easter Islanders.[110] Influenced by Heyerdahl's romantic interpretation of Easter's history, Diamond insists that the disappearance of the island's trees seems to coincide with a decline of its civilization around the 17th and 18th centuries, alongside declines of fish bones in middens (suggesting a decline in fishing) and then declines in bird bones, which he attributes to habitat loss. He notes that they stopped making statues at that time and started destroying the ahu. But the link is weakened because the Bird Man cult continued to thrive and survived the great impact caused by the arrival of explorers, whalers, sandalwood traders, and slave raiders.

Benny Peiser[5] noted evidence of self-sufficiency when Europeans first arrived. The island still had smaller trees, mainly toromiro, which became extinct in the wild in the 20th century probably because of slow growth and changes in the island's ecosystem. Cornelis Bouman, Jakob Roggeveen's captain, stated in his logbook, "... of yams, bananas and small coconut palms we saw little and no other trees or crops." According to Carl Friedrich Behrens, Roggeveen's officer, "The natives presented palm branches as peace offerings." According to ethnographer Alfred Mètraux, the most common type of house was called "hare paenga" (and is known today as "boathouse") because the roof resembled an overturned boat. The foundations of the houses were made of buried basalt slabs with holes for wooden beams to connect with each other throughout the width of the house. These were then covered with a layer of totora reed, followed by a layer of woven sugarcane leaves, and lastly a layer of woven grass.

Peiser claims that these reports indicate that large trees existed at that time, which is perhaps contradicted by the Bouman quote above. Plantations were often located farther inland, next to foothills, inside open-ceiling lava tubes, and in other places protected from the strong salt winds and salt spray affecting areas closer to the coast. It is possible many of the Europeans did not venture inland. The statue quarry, only one kilometre (5⁄8 mile) from the coast with an impressive cliff 100 m (330 ft) high, was not explored by Europeans until well into the 19th century.

Easter Island has suffered from heavy soil erosion in recent centuries, aggravated by massive historic deforestation alongside modern sheep farming throughout most of the 20th century. Jakob Roggeveen reported that Easter Island was exceptionally fertile. "Fowls are the only animals they keep. They cultivate bananas, sugar cane, and above all sweet potatoes." In 1786 Jean-François de La Pérouse visited Easter Island and his gardener declared that "three days' work a year" would be enough to support the population. Rollin, a major in the Pérouse expedition, wrote, "Instead of meeting with men exhausted by famine... I found, on the contrary, a considerable population, with more beauty and grace than I afterwards met in any other island; and a soil, which, with very little labor, furnished excellent provisions, and in an abundance more than sufficient for the consumption of the inhabitants."[112] The islanders' innovation of lithic mulching - the practice of covering fields with gravel or rocks to trap moisture and improve soil fertility - is a well-known and effective practice in dry areas of the premodern world.[113]

According to Diamond, the oral traditions (the veracity of which has been questioned by Routledge, Lavachery, Mètraux, Peiser, and others) of the current islanders seem obsessed with cannibalism, which he offers as evidence supporting a rapid collapse. For example, he states, to severely insult an enemy one would say, "The flesh of your mother sticks between my teeth." This, Diamond asserts, means the food supply of the people ultimately ran out.[114] Cannibalism, however, was widespread across Polynesian cultures.[115] Human bones have not been found in earth ovens other than those behind the religious platforms, indicating that cannibalism in Easter Island was a ritualistic practice. Contemporary ethnographic research has proven there is scarcely any tangible evidence for widespread cannibalism anywhere and at any time on the island.[116] The first scientific exploration of Easter Island (1914) recorded that the indigenous population strongly rejected allegations that they or their ancestors had been cannibals.[38]

Culture

Mythology

The most important myths are:[citation needed]

- Tangata manu, the Birdman cult which was practised until the 1860s.

- Makemake, an important god.

- Aku-aku, the guardians of the sacred family caves.

- Moai-kava-kava a ghost man of the Hanau epe (long-ears.)

- Hekai ite umu pare haonga takapu Hanau epe kai noruego, the sacred chant to appease the aku-aku before entering a family cave.

Stone work

The Rapa Nui people had a Stone Age culture and made extensive use of local stone:

- Basalt, a hard, dense stone used for toki and at least one of the moai.

- Obsidian, a volcanic glass with sharp edges used for sharp-edged implements such as Mataa and for the black pupils of the eyes of the moai.

- Red scoria from Puna Pau, a very light red stone used for the pukao and a few moai.

- Tuff from Rano Raraku, a much more easily worked rock than basalt that was used for most of the moai.

Moai (statues)

The large stone statues, or moai, for which Easter Island is famous, were carved in the period 1100–1680 CE (rectified radio-carbon dates).[18] A total of 887 monolithic stone statues have been inventoried on the island and in museum collections.[117] Although often identified as "Easter Island heads", the statues have torsos, most of them ending at the top of the thighs; a small number are complete figures that kneel on bent knees with their hands over their stomachs.[118][119] Some upright moai have become buried up to their necks by shifting soils.

Almost all (95%)[citation needed] moai were carved from compressed, easily worked solidified volcanic ash or tuff, found at a single site on the side of the extinct volcano Rano Raraku. The native islanders who carved them used only stone hand chisels, mainly basalt toki, which lie in place all over the quarry. The stone chisels were sharpened by chipping off a new edge when dulled. While sculpting was going on, the volcanic stone was splashed with water to soften it. While many teams worked on different statues at the same time, a single moai took a team of five or six men approximately a year to complete. Each statue represented the deceased head of a lineage.[citation needed]

Only a quarter of the statues were installed. Nearly half remained in the quarry at Rano Raraku, and the rest sat elsewhere, presumably on their way to intended locations. The largest moai raised on a platform is known as "Paro". It weighs 82 tonnes (90 short tons) and is 9.89 m (32 ft 5 in) long.[120][121] Several other statues of similar weight were transported to ahu on the north and south coasts.

Possible means by which the statues were moved include employment of a miro manga erua, a Y-shaped sledge with cross pieces, pulled with ropes made from the tough bark of the hau tree[122] and tied around the statue's neck. Anywhere from 180 to 250 men were required for pulling, depending on the size of the moai. Among other researchers on moving and erecting the moai was Vince Lee, who reenacted a moai moving scenario. Some 50 of the statues were re-erected in modern times. One of the first was on Ahu Ature Huke in Anakena beach in 1956.[123] It was raised using traditional methods during a Heyerdahl expedition.

Another method that might have been used to transport the moai would be to attach ropes to the statue and rock it, tugging it forward as it rocked. This would fit the legend of the Mo'ai 'walking' to their final locations.[124][125][126] This might have been managed by as few as 15 people, supported by the following evidence:

- The heads of the moai in the quarry are sloped forward, whereas the ones moved to final locations are not. This would serve to provide a better centre of gravity for transport.

- The statues found along the transport roads have wider bases than statues installed on ahu; this would facilitate more stable transport. Studies have shown fractures along the bases of the statues in transport; these could have arisen from rocking the statue back and forth and placing great pressures on the edges. The statues found mounted on ahu do not have wide bases, and stone chips found at the sites suggest they were further modified on placement.

- The abandoned and fallen statues near the old roads are found (more often than would be expected from chance) face down on ascending grades and on their backs when headed uphill. Some were documented standing upright along the old roads, e.g., by a party from Captain Cook's voyage that rested in the shade of a standing statue. This would be consistent with upright transport.

There is debate regarding the effects of the monument creation process on the environment. Some believe that the process of creating the moai caused widespread deforestation and ultimately a civil war over scarce resources.[127]

In 2011, a large moai statue was excavated from the ground.[128] During the same excavation program, some larger moai were found to have complex dorsal petroglyphs, revealed by deep excavation of the torso.[129]

In 2020, a pickup truck crashed into and destroyed a moai statue due to brake failure. No one was injured in the incident.[130][131]

- Moais

-

Tukuturi, an unusual bearded kneeling moai

-

All fifteen standing moai at Ahu Tongariki, excavated and restored in the 1990s

-

Ahu Akivi, one of the few inland ahu, with the only moai facing the ocean

Ahu (stone platforms)

Ahu are stone platforms. Varying greatly in layout, many were reworked during or after the huri mo'ai or statue-toppling era; many became ossuaries, one was dynamited open, and Ahu Tongariki was swept inland by a tsunami. Of the 313 known ahu, 125 carried moai – usually just one, probably because of the shortness of the moai period and transportation difficulties. Ahu Tongariki, one km (0.62 mi) from Rano Raraku, had the most and tallest moai, 15 in total.[132] Other notable ahu with moai are Ahu Akivi, restored in 1960 by William Mulloy, Nau Nau at Anakena and Tahai. Some moai may have been made from wood and were lost.

The classic elements of ahu design are:

- A retaining rear wall several feet high, usually facing the sea

- A front wall made of rectangular basalt slabs called paenga

- A fascia made of red scoria that went over the front wall (platforms built after 1300)

- A sloping ramp in the inland part of the platform, extending outward like wings

- A pavement of even-sized, round water-worn stones called poro

- An alignment of stones before the ramp

- A paved plaza before the ahu. This was called marae

- Inside the ahu was a fill of rubble.

On top of many ahu would have been:

- Moai on squarish "pedestals" looking inland, the ramp with the poro before them.

- Pukao or Hau Hiti Rau on the moai heads (platforms built after 1300).

- When a ceremony took place, "eyes" were placed on the statues. The whites of the eyes were made of coral, the iris was made of obsidian or red scoria.

Ahu evolved from the traditional Polynesian marae. In this context, ahu referred to a small structure sometimes covered with a thatched roof where sacred objects, including statues, were stored. The ahu were usually adjacent to the marae or main central court where ceremonies took place, though on Easter Island, ahu and moai evolved to much greater size. There the marae is the unpaved plaza before the ahu. The biggest ahu is 220 m (720 ft) and holds 15 statues, some of which are 9 m (30 ft) high. The filling of an ahu was sourced locally (apart from broken, old moai, fragments of which have been used in the fill).[111] Individual stones are mostly far smaller than the moai, so less work was needed to transport the raw material, but artificially leveling the terrain for the plaza and filling the ahu was laborious.

Ahu are found mostly on the coast, where they are distributed densely and fairly evenly. The exceptions are the western slopes of Mount Terevaka and the Rano Kau and Poike headlands, where they are much sparser. These are the three areas with the least low-lying coastal land and, apart from Poike, the furthest areas from Rano Raraku. One ahu with several moai was recorded on the cliffs at Rano Kau in the 1880s but had fallen to the beach before the Routledge expedition.[38] At least three recorded on Poike in the 1930s have also since disappeared.[133][134]

Stone walls

One of the highest-quality examples of Easter Island stone masonry is the rear wall of the ahu at Vinapu. Made without mortar by shaping hard basalt rocks of up to 7,000 kg (6.9 long tons; 7.7 short tons) to match each other exactly, it has a superficial similarity to some Inca stone walls in South America.[135]

Stone houses

Two types of houses are known from the past: hare paenga, a house with an elliptical foundation, made with basalt slabs and covered with a thatched roof that resembled an overturned boat, and hare oka, a round stone structure. Related stone structures called Tupa look very similar to the hare oka, except that the Tupa were inhabited by astronomer-priests and located near the coast, where the movements of the stars could be easily observed. Settlements also contain hare moa ("chicken house"), oblong stone structures that housed chickens. The houses at the ceremonial village of Orongo are unique in that they are shaped like hare paenga but are made entirely of flat basalt slabs found inside Rano Kao crater. The entrances to all the houses are very low, and entry requires crawling.

In early times the people of Rapa Nui reportedly sent the dead out to sea in small funerary canoes, as did their Polynesian counterparts on other islands. They later started burying people in secret caves to save the bones from desecration by enemies. During the turmoil of the late 18th century, the islanders seem to have started to bury their dead in the space between the belly of a fallen moai and the front wall of the structure. During the time of the epidemics they made mass graves that were semi-pyramidal stone structures.

Petroglyphs

Easter Island has one of the richest collections of petroglyphs in all Polynesia. Around 1,000 sites with more than 4,000 petroglyphs are catalogued. Designs and images were carved out of rock for a variety of reasons: to create totems, to mark territory, or to memorialize a person or event. There are distinct variations around the island in the frequency of themes among petroglyphs, with a concentration of Birdmen at Orongo. Other subjects include sea turtles, Komari (vulvas) and Makemake, the chief god of the Tangata manu or Birdman cult.[136]

- Petroglyphs

-

Fish petroglyph found near Ahu Tongariki

Caves

The island[137] and neighbouring Motu Nui are riddled with caves, many of which show signs of past human use for planting and as fortifications, including narrowed entrances and crawl spaces with ambush points. Many caves feature in the myths and legends of the Rapa Nui.[138]

Stone aerophone

The Pu o Hiro (Trumpet of Hiro) is a 1.25 metres (4 ft 1 in) high ancient stone aerophone on the north coast of Easter Island.[139] It was once used by the Rapa Nui as a musical instrument in fertility rituals.[140][141][142][139] The stone is covered in petroglyphs called komari which represent fertility.[139] By skillfully blowing wind in the top hole it makes a deep, trumpeting sound to invoke the god of rain Hiro in Polynesian mythology.[139]

Rongorongo

Easter Island once had an apparent script called rongorongo. Glyphs include pictographic and geometric shapes; the texts were incised in wood in reverse boustrophedon direction. It was first reported by French missionary Eugène Eyraud in 1864. At that time, several islanders said they could understand the writing, but according to tradition, only ruling families and priests were ever literate, and none survived the slave raids and subsequent epidemics. Despite numerous attempts, the surviving texts have not been deciphered, and without decipherment it is not certain that they are actually writing. Part of the problem is the small amount that has survived: only two dozen texts, none of which remain on the island. There are also only a couple of similarities with the petroglyphs on the island.[143]

Wood carving

|

|

| Skeletal statuette | Atypical portly statuette |

Wood was scarce on Easter Island during the 18th and 19th centuries, but a number of highly detailed and distinctive carvings have found their way to the world's museums. Particular forms include:[144]

- Reimiro, a gorget or breast ornament of crescent shape with a head at one or both tips.[145] The same design appears on the flag of Rapa Nui. Two Rei Miru at the British Museum are inscribed with Rongorongo.

- Moko Miro, a man with a lizard head. The Moko Miro was used as a club because of the legs, which formed a handle shape. If it was not held by hand, dancers wore it around their necks during feasts. The Moko Miro would also be placed at the doorway to protect the household from harm. It would be hanging from the roof or set in the ground. The original form had eyes made from white shells, and the pupils were made of obsidian.[146]

- Moai kavakava are male carvings and the Moai Paepae are female carvings.[147] These grotesque and highly detailed human figures, carved from Toromiro pine, represent ancestors. Sometimes these statues were used for fertility rites. Usually, they are used for harvest celebrations; "the first picking of fruits was heaped around them as offerings". When the statues were not used, they would be wrapped in bark cloth and kept at home. There were a few times that are reported when the islanders would pick up the figures like dolls and dance with them.[147] The earlier figures are rare and generally depict a male figure with an emaciated body and a goatee. The figures' ribs and vertebrae are exposed and many examples show carved glyphs on various parts of the body but more specifically, on the top of the head. The female figures, rarer than the males, depict the body as flat and often with the female's hand lying across the body. The figures, although some were quite large, were worn as ornamental pieces around a tribesman's neck. The more figures worn, the more important the man. The figures have a shiny patina developed from constant handling and contact with human skin.[citation needed]

- Ao, a large dancing paddle

21st-century culture

The Rapanui sponsor an annual festival, the Tapati, held since 1975 around the beginning of February to celebrate Rapa Nui culture. The islanders also maintain a national football team and three discos in the town of Hanga Roa. Other cultural activities include a musical tradition that combines South American and Polynesian influences and woodcarving.

Sports

The Chilean leg of the Red Bull Cliff Diving World Series takes place on the Island of Rapa Nui.

Tapati Festival

Tapati Rapa Nui festival ("week festival" in the local language) is an annual two-week long festival celebrating Easter Island culture.[148] The Tapati is centered around a competition between two families/ clans competing in various competitions to earn points. The winning team has their candidate crowned 'queen' of the island for the next year. The competitions are a way to maintain and celebrate traditional cultural activities such as cooking, jewelry-making, woodcarving, and canoeing.[149]

Demographics

2012 census

Population at the 2012 census was 5,761 (increased from 3,791 in 2002).[150] In 2002, 60% were persons of indigenous Rapa Nui origin, 39% were mainland Chileans (or their Easter Island-born descendants) of European (mostly Spanish) or mestizo (mixed European and indigenous Chilean Amerindian) origin and Easter Island-born mestizos of European and Rapa Nui and/or native Chilean descent, and the remaining 1% were indigenous mainland Chilean Amerindians (or their Easter Island-born descendants).[151] As of 2012[update], the population density on Easter Island was 35/km2 (91/sq mi).

Demographic history

The 1982 population was 1,936. The increase in population in the last census was partly caused by the arrival of people of European or mixed European and Native American descent from the Chilean mainland. However, most married a Rapa Nui spouse. Around 70% of the population were natives. Estimates of the pre-European population range from 7–17,000. Easter Island's all-time low of 111 inhabitants was reported in 1877. Out of these 111 Rapa Nui, only 36 had descendants, and all of today's Rapa Nui claim descent from those 36.

Languages

Easter Island's traditional language is Rapa Nui, an Eastern Polynesian language, sharing some similarities with Hawaiian and Tahitian. However, as in the rest of mainland Chile, the official language used is Spanish. Easter Island is the only territory in Polynesia where Spanish is an official language.

It is supposed[152] that the 2,700 indigenous Rapa Nui living in the island have a certain degree of knowledge of their traditional language; however, census data does not exist on the primary known and spoken languages among Easter Island's inhabitants and there are recent claims that the number of fluent speakers is as low as 800.[153] Indeed, Rapa Nui has been declining in its number of speakers as the island undergoes Hispanicization, because the island is under the jurisdiction of Chile and is now home to a number of Chilean continentals, most of whom speak only Spanish. For this reason, most Rapa Nui children now grow up speaking Spanish, and those who do learn Rapa Nui begin learning it later in life.[154] Even with efforts to revitalize the language,[155] Ethnologue has established that Rapa Nui is currently a threatened language.[152]

Easter Island's indigenous Rapa Nui toponymy has survived with few Spanish additions or replacements, a fact that has been attributed in part to the survival of the Rapa Nui language.[156]

Administration and legal status

Easter Island shares with Juan Fernández Islands the constitutional status of "special territory" of Chile, granted in 2007. As of 2011[update] a special charter for the island was under discussion in the Chilean Congress.

Administratively, the island is a province (Isla de Pascua Province) of the Valparaíso Region and contains a single commune (comuna) (Isla de Pascua). Both the province and the commune are called Isla de Pascua and encompass the whole island and its surrounding islets and rocks, plus Isla Salas y Gómez, some 380 km (240 mi) to the east. The provincial governor is appointed by the President of the Republic.[157] The municipal administration is located in Hanga Roa, led by a mayor and a six-member municipal council, all directly elected for a four-year mandate.

In August 2018, a law took effect prohibiting non-residents from staying on the island for more than 30 days.[158]

Since 1966 rape, sexual abuse and crimes against property in Easter Island had lower sentences than corresponding offences in mainland Chile.[159] This law was repealled in 2021 by a Constitutional Court decree.[160]

Notable people

- Policarpo Toro (1856–1921), a Chilean naval officer, took possession of the island on behalf of Chile.

- Monsignor Rafael Edwards Salas, (1878–1938), a Chilean priest, professor, and bishop who served as the military vicar of Chile and specially in the island.

- Felipe González de Ahedo (1714–1802), a Spanish navigator and cartographer; annexed Easter Island in 1770.

- Angata (c. 1853–1914), native catechist and prophetess who led a 1914 rebellion

- Thomas Barthel (1923–1997) a German ethnologist and epigrapher

- Carmen Cardinali (born 1944) a Rapa Nui Chilean professor, governor of Easter Island, 2010–2014.

- Jean-Baptiste Dutrou-Bornier (1834–1876) a French mariner, removed many of the Rapa Nui people and turned the island into a sheep ranch.

- Sebastian Englert (1888–1969), missionary and ethnologist

- Eugène Eyraud (1820–1868), missionary

- Thor Heyerdahl (1914–2002), a Norwegian adventurer and ethnographer

- Melania Hotu (born 1959), governor (2006–2010, 2015–2018)

- Marta Hotus Tuki (born 1969), governor (2014–2015)

- Riro Kāinga (died 1898 or 1899), last person to hold title of king and rule before Chilean consolidation

- Kings of Easter Island

- Hotu Matuꞌa, island founder

- William Mulloy (1917–1978), an American anthropologist and archaeologist

- Nga'ara (died 1859), one of the last 'ariki

- Jacobo Hey Paoa, first Rapa Nui male to earn a law degree and become an attorney

- Juan Edmunds Rapahango (1923–2012), former mayor

- Pedro Edmunds Paoa (born 1961), mayor and former governor

- Laura Alarcón Rapu, governor from 2018 to 2022

- Tiare Aguilera Hey, member of the Chilean Constitutional Convention

- Hippolyte Roussel (1824–1898), a French priest and missionary

- Katherine Routledge (1866–1935), an English archaeologist and anthropologist

- Alexander Ariʻipaea Salmon (1855–1914) English-Jewish-Tahitian de facto ruler of Easter Island, 1878–1888.

- Mahani Teave (born 1983), a Chilean American classical pianist

- Atamu Tekena (c. 1850–1892), missionary installed King who ceded island to Chile

- José Fati Tepano, first Rapa Nui male to serve as a titular judge upon completing training in Chile

- Juan Tepano (1867–1947), indigenous leader and cultural informant

- Valentino Riroroko Tuki (1932–2017) last claimant to the Rapa Nui throne

- Lynn Rapu Tuki (born 1969), head-teacher, promotes the arts and traditions of the Rapa Nui People.

- Luz Zasso Paoa a Rapa Nui politician, mayor of Easter Island, 2008–2012.

Transportation

Easter Island is served by Mataveri International Airport, with jet service (currently Boeing 787s) from LATAM Chile and, seasonally, subsidiaries such as LATAM Perú.

Gallery

-

Hanga Roa town hall

-

Polynesian dancing with feather costumes is on the tourist itinerary.

-

Fishing boats

-

Front view of the Catholic Church, Hanga Roa

-

Interior view of the Catholic Church in Hanga Roa

See also

References

- ^ "Censo 2017". National Statistics Institute (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 11 May 2018. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- ^ a b "Censo de Población y Vivienda 2002". National Statistics Institute. Archived from the original on 15 July 2010. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- ^ a b c d Hunt, T. (2006). "Rethinking the Fall of Easter Island". American Scientist. 94 (5): 412. doi:10.1511/2006.61.1002.