(612911) 2004 XR190

Hubble Space Telescope image of 2004 XR190, taken on October 2010 | |

| Discovery[1][2] | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by | CFEPS |

| Discovery site | Mauna Kea Obs. (first observed only) |

| Discovery date | 11 December 2004 |

| Designations | |

| (612911) 2004 XR190 | |

| Buffy (nickname)[3] | |

| Orbital characteristics[4] | |

| Epoch 27 April 2019 (JD 2458600.5) | |

| Uncertainty parameter 3 | |

| Observation arc | 14.74 yr (5,383 d) |

| Earliest precovery date | 6 December 2002[4][1] |

| Aphelion | 63.401 AU |

| Perihelion | 51.110 AU |

| 57.255 AU | |

| Eccentricity | 0.1073 |

| 433.24 yr (158,242 d) | |

| 277.05° | |

| 0° 0m 8.28s / day | |

| Inclination | 46.794° |

| 252.40° | |

| ≈ 4 April 2117[8] ±1 month | |

| 285.56° | |

| Physical characteristics | |

(612911) 2004 XR190, informally nicknamed Buffy, is a trans-Neptunian object, classified as both a scattered disc object and a detached object, located in the outermost region of the Solar System. It was first observed on 11 December 2004, by astronomers with the Canada–France Ecliptic Plane Survey at the Mauna Kea Observatories, Hawaii, United States.[1][2] It is the largest known highly inclined (> 45°) object. With a perihelion of 51 AU, it belongs to a small and poorly understood group of very distant objects with moderate eccentricities.[10]

Discovery and naming

[edit]2004 XR190 was discovered on 11 December 2004.[1] It was discovered by astronomers led by (Rhiannon) Lynne Allen of the University of British Columbia as part of the Canada–France Ecliptic Plane Survey (CFEPS) using the Canada–France–Hawaii Telescope (CFHT) near the ecliptic. The team included Brett Gladman, John Kavelaars, Jean-Marc Petit, Joel Parker and Phil Nicholson.[2] In 2015, six precovery images from 2002 and 2003 were found in Sloan Digital Sky Survey data.

The object was nicknamed "Buffy" by the discovery team, after the fictional vampire slayer Buffy Summers, and the team proposed several Inuit-based official names to the International Astronomical Union.[3]

Orbit and classification

[edit]

2004 XR190 orbits the Sun at a distance of 51.1–63.4 AU once every 433 years and 3 months (158,242 days; semi-major axis of 57.26 AU). Its orbit has a moderate eccentricity of 0.11 and a high inclination of 47° with respect to the ecliptic.[4]

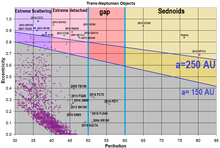

It belongs to the same group as 2014 FC72, 2014 FZ71, 2015 FJ345 and 2015 KQ174 (also see diagram), that are poorly understood for their large perihelia combined with moderate eccentricities. Considered a scattered and detached object,[5][6][7] 2004 XR190 is particularly unusual as it has an unusually circular orbit for a scattered-disc object (SDO). Although it is thought that traditional scattered-disc objects have been ejected into their current orbits by gravitational interactions with Neptune, the low eccentricity of its orbit and the distance of its perihelion (SDOs generally have highly eccentric orbits and perihelia less than 38 AU) seems hard to reconcile with such celestial mechanics. This has led to some uncertainty as to the current theoretical understanding of the outer Solar System. The theories include close stellar passages, unseen planet/rogue planets/planetary embryos in the early Kuiper belt, and resonance interaction with an outward-migrating Neptune. The Kozai mechanism is capable of transferring orbital eccentricity to a higher inclination.[10]

The object is the largest object with an inclination larger than 45°,[15] traveling further "up and down" than "left to right" around the Sun when viewed edge-on along the ecliptic.

Most distant objects

[edit]2004 XR190 came to aphelion around 1901.[16] Other than long-period comets, it is currently about the thirteenth-most-distant known large body (57.5 AU) in the Solar System with a well-known orbit, after Eris and Dysnomia (96.3 AU), Gonggong (87.4 AU), Sedna (85.9 AU), 2014 FC69 (84.0 AU), 2006 QH181 (83.3 AU), 2012 VP113 (83.3 AU), 2013 FY27 (80.3 AU), 2010 GB174 (70.5 AU), 2000 CR105 (60.3 AU), 2003 QX113 (59.8 AU), and 2008 ST291 (59.6 AU).[3][17]

Physical characteristics

[edit]With assumed albedos between 0.04 and 0.25, and absolute magnitudes from 4.3 to 4.6, 2004 XR190 has an estimated diameter of 335 to 850 kilometers; the mean arrived at by considering the two single-figure estimates plus the centre points of the three ranges is 562 km, approximately a quarter the diameter of Pluto.[7][9][10][11][12][13]

As of 2018, no well-documented spectral type and color indices, nor a rotational lightcurve have been obtained from spectroscopic and photometric observations; however, the Johnston's Archive lists a "taxonomic type" of "BR", and a "B-R magnitude" of 1.24.[7] The rotation period, pole and shape officially remain unknown.

Gallery

[edit]-

Orbital diagram of 2004 XR190 (Earth's orbit in the center is for scale)

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i "2004 XR190". Minor Planet Center. Retrieved 13 December 2018.

- ^ a b c "MPEC 2005-X72 : 2004 XR190". IAU Minor Planet Center. 12 December 2005. Retrieved 13 December 2018. (K04XJ0R)

- ^ a b c Maggie McKee. "Strange new object found at edge of Solar System". New Scientist. Retrieved 13 December 2018.

- ^ a b c d e "JPL Small-Body Database Browser: (2004 XR190)" (2017-09-01 last obs.). Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Retrieved 13 December 2018.

- ^ a b Jewitt, David, Morbidelli, Alessandro, & Rauer, Heike. (2007). Trans-Neptunian Objects and Comets: Saas-Fee Advanced Course 35. Swiss Society for Astrophysics and Astronomy. Berlin: Springer. ISBN 3-540-71957-1.

- ^ a b Lykawka, Patryk Sofia; Mukai, Tadashi (July 2007). "Dynamical classification of trans-neptunian objects: Probing their origin, evolution, and interrelation". Icarus. 189 (1): 213–232. Bibcode:2007Icar..189..213L. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2007.01.001.

- ^ a b c d e f Johnston, Wm. Robert (7 October 2018). "List of Known Trans-Neptunian Objects". Johnston's Archive. Retrieved 13 December 2018.

- ^ JPL Horizons Observer Location: @sun (Perihelion occurs when deldot changes from negative to positive. Uncertainty in time of perihelion is 3-sigma.)

- ^ a b c d Schaller, E. L.; Brown, M. E. (April 2007). "Volatile Loss and Retention on Kuiper Belt Objects" (PDF). The Astrophysical Journal. 659 (1): I.61–I.64. Bibcode:2007ApJ...659L..61S. doi:10.1086/516709. S2CID 10782167. Retrieved 13 December 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g Allen, R. L.; Gladman, B.; Kavelaars, J. J.; Petit, J.-M.; Parker, J. W.; Nicholson, P. (March 2006). "Discovery of a Low-Eccentricity, High-Inclination Kuiper Belt Object at 58 AU". The Astrophysical Journal. 640 (1): L83–L86. arXiv:astro-ph/0512430. Bibcode:2006ApJ...640L..83A. doi:10.1086/503098. S2CID 15588453. (Discovery paper)

- ^ a b c d Brown, Michael E. "How many dwarf planets are there in the outer solar system?". California Institute of Technology. Retrieved 13 December 2018.

- ^ a b c "2004 XR190". AstDyS-2, Asteroids Dynamic Site. Retrieved 18 August 2019.

- ^ a b c d Dan Bruton. "Conversion of Absolute Magnitude to Diameter for Minor Planets". Stephen F. Austin State University, College of Sciences and Mathematics, Department of Physics, Engineering and Astronomy. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 15 August 2019.

- ^ 2021 occultation

- ^ "JPL Small-Body Database Search Engine: H < 6.5 (mag)". JPL Solar System Dynamics. Retrieved 27 March 2014.

- ^ "Horizon Online Ephemeris System". California Institute of Technology, Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Retrieved 23 March 2009.

- ^ "List of minor planets more than 57.0 AU from the Sun". AstDyS-2, Asteroids – Dynamic Site, Department of Mathematics, University of Pisa, Italy. Retrieved 13 December 2018.

External links

[edit]- MPEC 2005-X72 : 2004 XR190, Minor Planet Electronic Circular, detailing discovery

- Discovery webpage by research team

- Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope Legacy Survey

- List Of Centaurs and Scattered-Disk Objects, Minor Planet Center

- (612911) 2004 XR190 at AstDyS-2, Asteroids—Dynamic Site

- (612911) 2004 XR190 at the JPL Small-Body Database