Square of opposition

This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2015) |

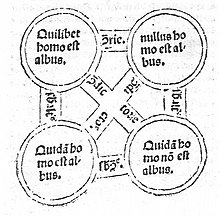

In term logic (a branch of philosophical logic), the square of opposition is a diagram representing the relations between the four basic categorical propositions. The origin of the square can be traced back to Aristotle's tractate On Interpretation and its distinction between two oppositions: contradiction and contrariety. However, Aristotle did not draw any diagram; this was done several centuries later by Apuleius and Boethius.

Summary

[edit]In traditional logic, a proposition (Latin: propositio) is a spoken assertion (oratio enunciativa), not the meaning of an assertion, as in modern philosophy of language and logic. A categorical proposition is a simple proposition containing two terms, subject (S) and predicate (P), in which the predicate is either asserted or denied of the subject.

Every categorical proposition can be reduced to one of four logical forms, named A, E, I, and O based on the Latin affirmo (I affirm), for the affirmative propositions A and I, and nego (I deny), for the negative propositions E and O. These are:

- The A proposition, the universal affirmative (universalis affirmativa), whose form in Latin is 'omne S est P', usually translated as 'every S is a P'.

- The E proposition, the universal negative (universalis negativa), Latin form 'nullum S est P', usually translated as 'no S are P'.

- The I proposition, the particular affirmative (particularis affirmativa), Latin 'quoddam S est P', usually translated as 'some S are P'.

- The O proposition, the particular negative (particularis negativa), Latin 'quoddam S nōn est P', usually translated as 'some S are not P'.

In tabular form:

| Name | Symbol | Latin | English* | Mnemonic | Modern form[1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Universal affirmative | A | Omne S est P. | Every S is P. (S is always P.) |

affirmo (I affirm) |

|

| Universal negative | E | Nullum S est P. | No S is P. (S is never P.) |

nego (I deny) |

|

| Particular affirmative | I | Quoddam S est P. | Some S is P. (S is sometimes P.) |

affirmo (I affirm) |

|

| Particular negative | O | Quoddam S nōn est P. | Some S is not P. (S is not always P.) |

nego (I deny) |

*Proposition A may be stated as "All S is P." However, Proposition E when stated correspondingly as "All S is not P." is ambiguous[2] because it can be either an E or O proposition, thus requiring a context to determine the form; the standard form "No S is P" is unambiguous, so it is preferred. Proposition O also takes the forms "Sometimes S is not P." and "A certain S is not P." (literally the Latin 'Quoddam S nōn est P.')

** in the modern forms means that a statement applies on an object . It may be simply interpreted as " is " in many cases. can be also written as .

Aristotle states (in chapters six and seven of the Peri hermēneias (Περὶ Ἑρμηνείας, Latin De Interpretatione, English 'On Interpretation')), that there are certain logical relationships between these four kinds of proposition. He says that to every affirmation there corresponds exactly one negation, and that every affirmation and its negation are 'opposed' such that always one of them must be true, and the other false. A pair of an affirmative statement and its negation is, he calls, a 'contradiction' (in medieval Latin, contradictio). Examples of contradictories are 'every man is white' and 'not every man is white' (also read as 'some men are not white'), 'no man is white' and 'some man is white'.

The below relations, contrary, subcontrary, subalternation, and superalternation, do hold based on the traditional logic assumption that things stated as S (or things satisfying a statement S in modern logic) exist. If this assumption is taken out, then these relations do not hold.

'Contrary' (medieval: contrariae) statements, are such that both statements cannot be true at the same time. Examples of these are the universal affirmative 'every man is white', and the universal negative 'no man is white'. These cannot be true at the same time. However, these are not contradictories because both of them may be false. For example, it is false that every man is white, since some men are not white. Yet it is also false that no man is white, since there are some white men.

Since every statement has the contradictory opposite (its negation), and since a contradicting statement is true when its opposite is false, it follows that the opposites of contraries (which the medievals called subcontraries, subcontrariae) can both be true, but they cannot both be false. Since subcontraries are negations of universal statements, they were called 'particular' statements by the medieval logicians.

Another logical relation implied by this, though not mentioned explicitly by Aristotle, is 'alternation' (alternatio), consisting of 'subalternation' and 'superalternation'. Subalternation is a relation between the particular statement and the universal statement of the same quality (affirmative or negative) such that the particular is implied by the universal, while superalternation is a relation between them such that the falsity of the universal (equivalently the negation of the universal) is implied by the falsity of the particular (equivalently the negation of the particular).[3] (The superalternation is the contrapositive of the subalternation.) In these relations, the particular is the subaltern of the universal, which is the particular's superaltern. For example, if 'every man is white' is true, its contrary 'no man is white' is false. Therefore, the contradictory 'some man is white' is true. Similarly the universal 'no man is white' implies the particular 'not every man is white'.[4][5]

In summary:

- Universal statements are contraries: 'every man is just' and 'no man is just' cannot be true together, although one may be true and the other false, and also both may be false (if at least one man is just, and at least one man is not just).

- Particular statements are subcontraries. 'Some man is just' and 'some man is not just' cannot be false together.

- The particular statement of one quality is the subaltern of the universal statement of that same quality, which is the superaltern of the particular statement because in Aristotelian semantics 'every A is B' implies 'some A is B' and 'no A is B' implies 'some A is not B'. Note that modern formal interpretations of English sentences interpret 'every A is B' as 'for any x, a statement that x is A implies a statement that x is B', which does not imply 'some x is A'. This is a matter of semantic interpretation, however, and does not mean, as is sometimes claimed, that Aristotelian logic is 'wrong'.

- The universal affirmative (A) and the particular negative (O) are contradictories. If some A is not B, then not every A is B. Conversely, though this is not the case in modern semantics, it was thought that if every A is not B, some A is not B. This interpretation has caused difficulties (see below). While Aristotle's Greek does not represent the particular negative as 'some A is not B, but as 'not every A is B', someone in his commentary on the Peri hermaneias, renders the particular negative as 'quoddam A nōn est B', literally 'a certain A is not a B', and in all medieval writing on logic it is customary to represent the particular proposition in this way.

These relationships became the basis of a diagram originating with Boethius and used by medieval logicians to classify the logical relationships. The propositions are placed in the four corners of a square, and the relations represented as lines drawn between them, whence the name 'The Square of Opposition'. Therefore, the following cases can be made:[6]

- If A is true, then E is false, I is true, O is false;

- If E is true, then A is false, I is false, O is true;

- If I is true, then E is false, A and O are indeterminate;

- If O is true, then A is false, E and I are indeterminate;

- If A is false, then O is true, E and I are indeterminate;

- If E is false, then I is true, A and O are indeterminate;

- If I is false, then A is false, E is true, O is true;

- If O is false, then A is true, E is false, I is true.

To memorize them, the medievals invented the following Latin rhyme:[7]

- A adfirmat, negat E, sed universaliter ambae;

I firmat, negat O, sed particulariter ambae.

It affirms that A and E are not neither both true nor both false in each of the above cases. The same applies to I and O. While the first two are universal statements, the couple I / O refers to particular ones.

The Square of Oppositions was used for the categorical inferences described by the Greek philosopher Aristotle: conversion, obversion and contraposition. Each of those three types of categorical inference was applied to the four Boethian logical forms: A, E, I, and O.

The problem of existential import

[edit]Subcontraries (I and O), which medieval logicians represented in the form 'quoddam A est B' (some particular A is B) and 'quoddam A non est B' (some particular A is not B) cannot both be false, since their universal contradictory statements (no A is B / every A is B) cannot both be true. This leads to a difficulty firstly identified by Peter Abelard (1079 – 21 April 1142). 'Some A is B' seems to imply 'something is A', in other words, there exists something that is A. For example, 'Some man is white' seems to imply that at least one thing that exists is a man, namely the man who has to be white, if 'some man is white' is true. But, 'some man is not white' also implies that something as a man exists, namely the man who is not white, if the statement 'some man is not white' is true. But Aristotelian logic requires that, necessarily, one of these statements (more generally 'some particular A is B' and 'some particular A is not B') is true, i.e., they cannot both be false. Therefore, since both statements imply the presence of at least one thing that is a man, the presence of a man or men is followed. But, as Abelard points out in the Dialectica, surely men might not exist?[8]

- For with absolutely no man existing, neither the proposition 'every man is a man' is true nor 'some man is not a man'.[9]

Abelard also points out that subcontraries containing subject terms denoting nothing, such as 'a man who is a stone', are both false.

- If 'every stone-man is a stone' is true, also its conversion per accidens is true ('some stones are stone-men'). But no stone is a stone-man, because neither this man nor that man etc. is a stone. But also this 'a certain stone-man is not a stone' is false by necessity, since it is impossible to suppose it is true.[10]

Terence Parsons (born 1939) argues that ancient philosophers did not experience the problem of existential import as only the A (universal affirmative) and I (particular affirmative) forms had existential import. (If a statement includes a term such that the statement is false if the term has no instances, i.e., no thing associated with the term exists, then the statement is said to have existential import with respect to that term.)

- Affirmatives have existential import, and negatives do not. The ancients thus did not see the incoherence of the square as formulated by Aristotle because there was no incoherence to see.[11]

He goes on to cite a medieval philosopher William of Moerbeke (1215–35 – c. 1286),

- In affirmative propositions a term is always asserted to supposit for something. Thus, if it supposits for nothing the proposition is false. However, in negative propositions the assertion is either that the term does not supposit for something or that it supposits for something of which the predicate is truly denied. Thus a negative proposition has two causes of truth.[12]

And points to Boethius' translation of Aristotle's work as giving rise to the mistaken notion that the O form has existential import.

- But when Boethius (477 – 524 AD) comments on this text he illustrates Aristotle's doctrine with the now-famous diagram, and he uses the wording 'Some man is not just'. So this must have seemed to him to be a natural equivalent in Latin. It looks odd to us in English, but he wasn't bothered by it.[13]

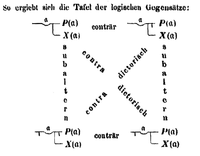

Modern squares of opposition

[edit]

The conträr below is an erratum:

It should read subconträr.

In the 19th century, George Boole (November 1815 – 8 December 1864) argued for requiring existential import on both terms in particular claims (I and O), but allowing all terms of universal claims (A and E) to lack existential import. This decision made Venn diagrams particularly easy to use for term logic. The square of opposition, under this Boolean set of assumptions, is often called the modern Square of opposition. In the modern square of opposition, A and O claims are contradictories, as are E and I, but all other forms of opposition cease to hold; there are no contraries, subcontraries, subalternations, and superalternations. Thus, from a modern point of view, it often makes sense to talk about 'the' opposition of a claim, rather than insisting, as older logicians did, that a claim has several different opposites, which are in different kinds of opposition with the claim.

Gottlob Frege (8 November 1848 – 26 July 1925)'s Begriffsschrift also presents a square of oppositions, organised in an almost identical manner to the classical square, showing the contradictories, subalternates and contraries between four formulae constructed from universal quantification, negation and implication.

Algirdas Julien Greimas (9 March 1917 – 27 February 1992)' semiotic square was derived from Aristotle's work.

The traditional square of opposition is now often compared with squares based on inner- and outer-negation.[14]

Logical hexagons and other bi-simplexes

[edit]The square of opposition has been extended to a logical hexagon which includes the relationships of six statements. It was discovered independently by both Augustin Sesmat (April 7, 1885 – December 12, 1957) and Robert Blanché (1898–1975).[15] It has been proven that both the square and the hexagon, followed by a "logical cube", belong to a regular series of n-dimensional objects called "logical bi-simplexes of dimension n." The pattern also goes even beyond this.[16]

Square of opposition (or logical square) and modal logic

[edit]The logical square, also called square of opposition or square of Apuleius, has its origin in the four marked sentences to be employed in syllogistic reasoning: "Every man is bad," the universal affirmative - The negation of the universal affirmative "Not every man is bad" (or "Some men are not bad") - "Some men are bad," the particular affirmative - and finally, the negation of the particular affirmative "No man is bad". Robert Blanché published with Vrin his Structures intellectuelles in 1966 and since then many scholars think that the logical square or square of opposition representing four values should be replaced by the logical hexagon which by representing six values is a more potent figure because it has the power to explain more things about logic and natural language.

Set-theoretical interpretation of categorical statements

[edit]In modern mathematical logic, statements containing words "all", "some" and "no", can be stated in terms of set theory if we assume a set-like domain of discourse. If the set of all A's is labeled as and the set of all B's as , then:

- "All A is B" (AaB) is equivalent to " is a subset of ", or .

- "No A is B" (AeB) is equivalent to "The intersection of and is empty", or .

- "Some A is B" (AiB) is equivalent to "The intersection of and is not empty", or .

- "Some A is not B" (AoB) is equivalent to " is not a subset of ", or .

By definition, the empty set is a subset of all sets. From this fact it follows that, according to this mathematical convention, if there are no A's, then the statements "All A is B" and "No A is B" are always true whereas the statements "Some A is B" and "Some A is not B" are always false. This also implies that AaB does not entail AiB, and some of the syllogisms mentioned above are not valid when there are no A's ().

See also

[edit]- Boole's syllogistic

- Free logic

- Logical cube

- Logical hexagon

- Octagon of Prophecies

- Triangle of opposition

References

[edit]- ^ Per The Traditional Square of Opposition: 1.1 The Modern Revision of the Square in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- ^ Kelley, David (2014). The Art of Reasoning: An Introduction to Logic and Critical Thinking (4 ed.). New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. p. 150. ISBN 978-0-393-93078-8.

- ^ "Introduction to Logic - 7.2.1 Finishing the Square and Immediate Inferences". 2021-08-10.

- ^ Parry & Hacker, Aristotelian Logic (SUNY Press, 1990), p. 158.

- ^ Cohen & Nagel, Introduction to Logic Second Edition (Hackett Publishing, 1993), p. 55.

- ^ Reale, Giovanni; Antiseri, Dario (1983). Il pensiero occidentale dalle origini a oggi. Vol. 1. Brescia: Editrice La Scuola. p. 356. ISBN 88-350-7271-9. OCLC 971192154.

- ^ Massaro, Domenico (2005). Questioni di verità: logica di base per capire e farsi capire. Script (in Italian). Vol. 2. Maples: Liguori Editore Srl. p. 58. ISBN 9788820738921. LCCN 2006350806. OCLC 263451944.

- ^ In his Dialectica, and in his commentary on the Perihermaneias

- ^ Re enim hominis prorsus non existente neque ea vera est quae ait: omnis homo est homo, nec ea quae proponit: quidam homo non est homo

- ^ Si enim vera est: Omnis homo qui lapis est, est lapis, et eius conversa per accidens vera est: Quidam lapis est homo qui est lapis. Sed nullus lapis est homo qui est lapis, quia neque hic neque ille etc. Sed et illam: Quidam homo qui est lapis, non est lapis, falsam esse necesse est, cum impossibile ponat

- ^ in The Traditional Square of Opposition in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- ^ (SL I.72) Loux 1974, 206

- ^ The Traditional Square of Opposition

- ^ Westerståhl, 'Classical vs. modern squares of opposition, and beyond', in Beziau and Payette (eds.), The Square of Opposition: A General Framework for Cognition, Peter Lang, Bern, 195-229.

- ^ N-Opposition Theory Logical hexagon

- ^ Moretti, Pellissier

External links

[edit]- Parsons, Terence. "The Traditional Square of Opposition". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- International Congress on the Square of Opposition

- Special Issue of Logica Universalis Vol. 2 N. 1 (2008) on the Square of Opposition

- Catlogic: An open source computer script written in Ruby to construct, investigate, and compute categorical propositions and syllogisms

- Periermenias Aristotelis with links to video and digitized manuscript LJS 101 of Boethius' Latin translation of Aristotle's De interpretatione, which contains 9th/11th century copies (some with color) of Aristotle's square of opposition on leaves 36r and 36v.