Magnum Force

| Magnum Force | |

|---|---|

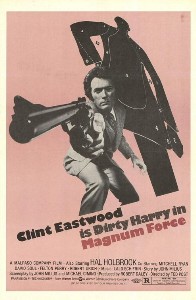

Theatrical release poster by Bill Gold | |

| Directed by | Ted Post |

| Screenplay by | John Milius Michael Cimino |

| Story by | John Milius |

| Based on | Characters by Harry Julian Fink R.M. Fink |

| Produced by | Robert Daley |

| Starring | Clint Eastwood Hal Holbrook Mitchell Ryan David Soul Felton Perry Robert Urich |

| Cinematography | Frank Stanley |

| Edited by | Ferris Webster |

| Music by | Lalo Schifrin |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. |

Release date |

|

Running time | 123 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Box office | $44.6 million (U.S.A.)[1] |

Magnum Force is a 1973 American neo-noir action thriller film and the second to feature Clint Eastwood as maverick cop Harry Callahan after the 1971 film Dirty Harry. Ted Post, who had previously worked with Eastwood on Rawhide and Hang 'Em High, directed the film. The screenplay was written by John Milius and Michael Cimino (who later worked with Eastwood on Thunderbolt and Lightfoot). The film score was composed by Lalo Schifrin. This film features early appearances by David Soul, Tim Matheson and Robert Urich. At 123 minutes, it is the longest of the five Dirty Harry films.

Plot

[edit]In 1973, after being acquitted of a mass murder on a legal technicality, mobster Carmine Ricca drives away from court in his limousine. While traveling on a city road, the driver is pulled over by a San Francisco Police Department (SFPD) motorcycle cop who calmly guns down all of the occupants in the car. Inspector Harry Callahan visits the crime scene with his new partner, Earlington "Early" Smith, despite the fact that the two are supposed to be on stakeout duty. Their superior, Lieutenant Neil Briggs, seems eager to keep Callahan out of the murder investigation.

While visiting the airport, Callahan helps deal with two men trying to hijack an airplane. He later meets rookie officers Phil Sweet, John Davis, Alan "Red" Astrachan and Mike Grimes while visiting the police firing range. Sweet is an ex-Army Ranger and Vietnam veteran with great marksmanship skills, and his friends are not that different. Elsewhere, a motorcycle cop shoots up a pool party, leaving no usable evidence of his crime.

As Callahan and Early take down criminals at a drugstore, a pimp murders a prostitute for withholding money from him. The next day, the pimp is killed by a patrolman. While investigating the scene, Callahan realizes that the culprit is a cop. He assumes the culprit to be his old friend Charlie McCoy, who has become despondent and suicidal after leaving his wife. Later, a motorcycle cop murders drug kingpin Lou Guzman. The killer, revealed to be Davis, encounters McCoy in the parking garage and guns him down.

At an annual shooting competition, Callahan learns that Davis was the first officer to arrive after the murders of Guzman and McCoy. He retrieves a slug from Davis' weapon and has ballistics match it to the bullets from the Guzman murder. Callahan begins to suspect that a secret death squad within the SFPD is responsible for the killings. Briggs insists that Ricca's former associate, Frank Palancio, is the real culprit. Callahan persuades Briggs to assign Davis and Sweet as backup for a raid on Palancio's offices. However, Palancio and his gang are tipped off via a phone call, Sweet is killed by a shotgun blast and all of Palancio's men die in the ensuing shootout. Palancio attempts to escape, but Callahan jumps on the hood of his car, causing him to lose control and crash into a crane, killing him.

Briggs angrily suspends Callahan for the death of Sweet. After returning home, Callahan finds Davis, Astrachan and Grimes waiting for him, presenting him with an ultimatum to side with them; Callahan refuses. While checking his mailbox, Callahan discovers a bomb left by the vigilantes and manages to defuse it. A second bomb, however, kills Early before Callahan can warn him.

Callahan learns that Briggs is the secret leader of the death squad. Briggs defends his actions, claiming that he is only doing what the broken legal system cannot; Harry responds that their methods will escalate until people are executed for minor crimes. He states he knows the system is flawed, but he's chosen to stand by it until someone comes up with something better. At gunpoint, Briggs orders Callahan to drive to an undisclosed location while being followed by Grimes. Callahan manages to disarm Briggs and force him out of the car before running Grimes over.

Davis and Astrachan appear, causing Callahan to flee onto a derelict aircraft carrier in a shipbreaker's yard. Callahan kills Astrachan and takes his motorcycle, leading Davis in a series of jumps between ships. The chase ends with Davis driving off the ship into San Francisco Bay and dying on impact. Callahan is then confronted at gunpoint by Briggs. The lieutenant mocks Callahan and threatens to have him prosecuted. As Callahan backs away from the car, he surreptitiously activates the timer on his mailbox bomb and tosses it in the back seat, which explodes and kills Briggs moments later. Callahan then repeats a comment similar to something he said to Briggs earlier: "A man's got to know his limitations."

Cast

[edit]- Clint Eastwood as Inspector "Dirty" Harry Callahan[note 1]

- Hal Holbrook as Lieutenant Neil Briggs

- David Soul as Officer John Davis

- Tim Matheson as Officer Phil Sweet

- Kip Niven as Officer Alan "Red" Astrachan

- Robert Urich as Officer Mike Grimes

- Felton Perry as Inspector Earlington "Early" Smith

- Mitchell Ryan as Officer Charlie McCoy

- Margaret Avery as Prostitute

- Bob McClurg as cab driver

- John Mitchum as Inspector Frank DiGiorgio[note 2]

- Albert Popwell as Pimp

- Clifford A. Pellow as Lou Guzman

- Richard Devon as Carmine Ricca

- Christine White as Carol McCoy

- Tony Giorgio as Frank Palancio

- Maurice Argent as Nat Weinstein

- Jack Kosslyn as Walter

- Bob March as Estabrook

- Adele Yoshioka as Sunny

- Will Hutchins as Stakeout Cop (uncredited)

- Suzanne Somers as newly engaged woman in pool (uncredited)

Production

[edit]Development

[edit]Writer John Milius came up with a storyline in which a group of young rogue officers in the SFPD systematically exterminate the city's worst criminals, conveying the idea that even worse rogue cops than Dirty Harry exist.[2] Terrence Malick had introduced the concept in an unused draft for the first film; director Don Siegel disliked the idea and had Malick's draft thrown out, but Clint Eastwood remembered it for this film. Eastwood specifically wanted to convey that, despite the 1971 film's perceived politics, Harry was not a complete vigilante. David Soul, Tim Matheson, Robert Urich, and Kip Niven were cast as the young vigilante cops.[3] Milius was a gun aficionado and political conservative, and the film would extensively feature gun shooting in practice, competition, and on the job.[3] Given this strong theme in the film, the title was soon changed from Vigilance to Magnum Force in deference to the .44 Magnum that Harry liked to use. Milius thought it was important to remind the audiences of the original film by incorporating the line "Do ya feel lucky?" repeated in the opening credits.[3]

With Milius committed to filming Dillinger, Michael Cimino was later hired to revise the script, overseen by Ted Post, who was to direct. According to Milius, his script did not contain any of the final action sequences (the car chase and climax on the aircraft carriers). His was a "simple script".[4] The addition of the character Sunny was done at the suggestion of Eastwood, who reportedly received letters from women asking for "a female to hit on Harry" (not the other way around).[4]

Milius later said he did not like the film and wished Don Siegel had directed it, as originally intended:

Of all the films I had anything to do with, I like it least. They changed a lot of things in a cheap and distasteful manner. The whole ending is wrong, it wasn't mine at all. All movies had a motorcycle or car chase at the time — except Westerns. They have a scene where this black girl's pimp forces Drano down her throat. In the script, they merely went into the morgue and Harry said, "I don't feel bad for that son of a b****, 'cause two weeks ago one of his girls was in here and he'd poured Drano down her throat." I think it's better to hear about it than to see it later; also, it goes right back to the character again; you understand Harry's feelings about it. All the stuff they put in about the Japanese girl - they put in a scene where the star gets to f*** some girl, and it's pretty hard to get it out. My Dirty Harry scripts never had Harry knowing any girls too well other than hookers, because he was a lonely guy who lived alone and didn't like to associate with people. He could never be close enough to a woman to have any sort of affair. A bitter, lonely man who liked his work.[5]

Directing

[edit]Eastwood himself was initially offered the role of director, but declined. Ted Post, who had previously directed Eastwood in Rawhide and Hang 'Em High, was hired. Buddy Van Horn was the second unit director. Both Eastwood and Van Horn went on to direct the final two entries in the series, Sudden Impact and The Dead Pool, respectively.

Filming

[edit]Frank Stanley was hired as cinematographer. Filming commenced in late April 1973.[3] During filming, Eastwood encountered numerous disputes with Post over who was calling the shots in directing the film, and Eastwood refused to authorize two important scenes directed by Post in the film because of time and expenses; one of them was at the climax to the film with a long shot of Eastwood on his motorcycle as he confronts the rogue cops.[6] As with many of his films, Eastwood was intent on shooting it as smoothly as possible, often refusing to do retakes over certain scenes. Post later remarked: "A lot of the things he said were based on pure, selfish ignorance, and showed that he was the man who controlled the power. By Magnum Force, Clint's ego began applying for statehood".[6] Post remained bitter with Eastwood for many years and claims disagreements over the filming affected his career afterwards.[7] According to second unit director of photography Rexford Metz, "Eastwood would not take the time to perfect a situation. If you've got 70% of a shot worked out, that's sufficient for him, because he knows his audience will accept it."[6]

Music

[edit]The orchestra, arranged and conducted by Lalo Schifrin, including[8]

Controversy

[edit]The film received negative publicity in 1974 when it was discovered that the scene where the prostitute is killed with drain cleaner had allegedly inspired the Hi-Fi murders, with the two killers believing the method would be as efficient as it was portrayed in the film. The killers said that they were looking for a unique murder method when they stumbled upon the film, and had they not seen the movie, would have chosen a method from another film. The drain cleaner reference was repeated in at least two other films, including Heathers (1988) and Urban Legend (1998). According to John Milius, this drain cleaner scene was never meant to be filmed, but was only mentioned in his original script.[4]

Release

[edit]Box office

[edit]In the film's opening week, it grossed $6,871,011 from 401 theatres.[9][10] In the United States, the film made a total of $44,680,473,[11] making it more successful than the first film[12] and the sixth highest-grossing film of 1973.

Theatrical rentals were $19.4 million in the United States and Canada and $9.5 million overseas for a worldwide total of $28.9 million.[13][14]

Reception

[edit]The New York Times critics such as Nora Sayre criticized the conflicting moral themes of the film, and Frank Rich believed it "was the same old stuff".[7] Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune gave the film two-and-a-half stars out of four and wrote: "The problem with Magnum Force is that this new side of Harry—his antivigilantism—is never made believable in the context of his continuing tendency to brandish his .44 magnum revolver as if it were his phallus. The new, 'Clean Harry' doesn't cut it. Some of the film's action sequences do."[15] Kevin Thomas of the Los Angeles Times found the film "too preoccupied in celebrating violence to keep it in focus."[16] Pauline Kael, a harsh critic of Eastwood's for many years, mocked his performance as Dirty Harry, commenting, "He isn't an actor, so one could hardly call him a bad actor. He'd have to do something before we could consider him bad at it. And acting isn't required of him in Magnum Force."[7] Gary Arnold of The Washington Post was positive, praising the film as "an ingenious and exciting crime thriller" with "a less self-righteous message" than the original Dirty Harry.[17] Gary Crowdus wrote in Cinéaste, "We are left with the comforting assurance that when we need him, Harry (and all the cops like him who do the 'dirty' jobs no one else wants) will be there protecting us from the lunatic fringes of both Left and Right. Sure, Harry may be a little trigger-happy, but at least he shoots the right people. The problem, however, one which the film raises but never resolves, is who determines the definition of 'right' people?"[18]

On Rotten Tomatoes, the film has a score of 67% based on 30 reviews, with the critic consensus being: "Magnum Force ups the ante for the Dirty Harry franchise with faster action and thrilling stuntwork."[19]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Magnum Force (1973)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on May 28, 2014. Retrieved May 26, 2014.

- ^ McGilligan (1999), p.233

- ^ a b c d McGilligan (1999), p.234

- ^ a b c John Milius commentary on Magnum Force Deluxe Edition DVD

- ^ Thompson, Richard (July 1976). "STOKED". Film Comment 12.4. pp. 10–21.

- ^ a b c McGilligan (1999), p.235

- ^ a b c McGilligan (1999), p.236

- ^ "Magnum Force". Library of Congress.

- ^ Munn, p. 142

- ^ "Magnum Force – Warner Bros. Advert". Variety. January 9, 1974. pp. 14–15.

- ^ "Magnum Force, Box Office Information". The Numbers. Archived from the original on May 31, 2012. Retrieved February 11, 2012.

- ^ "Dirty Harry Franchise Box Office Information". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on May 5, 2012. Retrieved February 11, 2012.

- ^ "All-time Film Rental Champs". Variety. January 7, 1976. p. 20.

- ^ Murphy, A.D. (December 29, 1976). "$205-$210-Mil Warner Rental Range". Variety. p. 3.

- ^ Siskel, Gene (December 27, 1973). "The best of these police thrillers comes away 'Laughing'". Chicago Tribune. Section 2, p. 2.

- ^ Thomas, Kevin (December 25, 1973). "A Violent 'Magnum' Arrives". Los Angeles Times. Part IV, p. 29.

- ^ Arnold, Gary (January 1, 1974). "Magnum Force". The Washington Post. C1.

- ^ Crowdus, Gary (1974). "Magnum Force". Cinéaste. Vol. VI, No. 2. p. 54.

- ^ "Magnum Force (2011)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Archived from the original on April 16, 2019. Retrieved January 16, 2024.

Bibliography

[edit]- McGilligan, Patrick (1999). Clint: The Life and Legend. London: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-00-638354-8.

- Munn, Michael (1992). Clint Eastwood: Hollywood's Loner. London: Robson Books. ISBN 0-86051-790-X.

- Street, Joe (2016). Dirty Harry's America: Clint Eastwood, Harry Callahan, and the Conservative Backlash. University Press of Florida. ISBN 978-0-8130-6167-2.

External links

[edit]- Magnum Force at IMDb

- Magnum Force at AllMovie

- Magnum Force at the TCM Movie Database

- Magnum Force at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- 1973 films

- 1970s action thriller films

- 1970s vigilante films

- American action thriller films

- American sequel films

- Dirty Harry

- Fictional portrayals of the San Francisco Police Department

- Films about police brutality

- Films about terrorism in the United States

- Films directed by Ted Post

- Films set in San Francisco

- Films set in the San Francisco Bay Area

- Films shot in San Francisco

- Films set in 1972

- American serial killer films

- Films about police corruption

- American vigilante films

- Films about police misconduct

- American police detective films

- Warner Bros. films

- Films with screenplays by John Milius

- Films scored by Lalo Schifrin

- American neo-noir films

- 1970s English-language films

- 1970s American films

- Films with screenplays by Michael Cimino