Robert E. Lee Monument (New Orleans)

Robert E. Lee Monument | |

The monument in 2015 | |

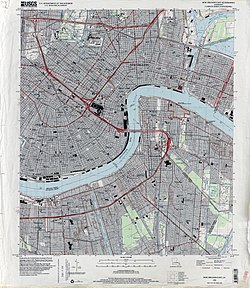

| Location | Lee Circle (900–1000 blocks St. Charles Avenue), New Orleans, Louisiana |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 29°56′35″N 90°4′20″W / 29.94306°N 90.07222°W |

| Built | 1884 |

| Built by | Roy, John |

| Sculptor | Alexander Doyle |

| NRHP reference No. | 91000254[1] |

| Added to NRHP | March 19, 1991 |

The Robert E. Lee Monument, formerly in New Orleans, Louisiana, is a historic statue dedicated to Confederate General Robert E. Lee by American sculptor Alexander Doyle. It was removed (intact) by official order and moved to an unknown location on May 19, 2017. Any future display is uncertain.[2]

History

[edit]

Efforts to raise funds to build the statue began after Lee's death in 1870 by the Robert E. Lee Monument Association, which by 1876 had raised the $36,400 needed. The association's president was Louisiana Supreme Court Justice Charles E. Fenner, a segregationist who wrote a lower court opinion in the Plessy v. Ferguson decision.[3] Sculptor Alexander Doyle was hired to sculpt the brass statue, which was installed in 1884. The granite base and pedestal was designed and built by John Ray [Roy], architect; contract dated 1877, at a cost of $26,474. John Hagan, a builder, was contracted to "furnish and set" the column at a cost of $9,350.[4] The monument was dedicated in 1884, at Tivoli Circle (since commonly called Lee Circle) on St. Charles Avenue. Dignitaries present at the dedication on February 22—George Washington's birthday—included former Confederate President Jefferson Davis, two daughters of General Lee—Mary Custis Lee and Mildred Childe Lee—and Confederate General P.G.T. Beauregard.[5]

The statue itself rises 16'6" tall, with an 8'4" base, standing on a 60' column with an interior staircase, according to a schematic released by the City of New Orleans on the day of the removal of the statue and its base, May 19, 2017.[6] The Lee statue faced "north where, as local lore has it, he can always look in the direction of his military adversaries."[7]

In January 1953, the statue of Lee was lifted from atop the column for repairs to the monument's foundation. The statue was returned to its perch in January the following year.[8]

The monument was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1991.[1][9] It was included by New Orleans magazine in June 2011 as one of the city's "11 important statues".[10]

Removal of the monument

[edit]On June 24, 2015, New Orleans Mayor Mitch Landrieu acknowledged the impact of the June 2015 Charleston church shooting, but credited a 2014 conversation with New Orleans jazz ambassador Wynton Marsalis for his decision to call for the removal of the Lee statue and renaming of Lee Circle and other city memorials dedicated to Confederate slaveholders.[11]

As part of a sixty-day period for public input, two city commissions called for the removal of four monuments associated with the Confederacy: the Lee statue, statues of Jefferson Davis and P.G.T. Beauregard, and an obelisk commemorating the Battle of Liberty Place. Governor Bobby Jindal opposed the removals.[12]

On December 15, 2015, Wynton Marsalis explained his reasons for advocating removal in The Times-Picayune: "When one surveys the accomplishments of our local heroes across time from Iberville and Bienville, to Andrew Jackson, from Mahalia Jackson, to Anne Rice and Fats Domino, from Wendell Pierce, to John Besh and Jonathan Batiste, what did Robert E. Lee do to merit his distinguished position? He fought for the enslavement of a people against our national army fighting for their freedom; killed more Americans than any opposing general in history; made no attempt to defend or protect this city; and even more absurdly, he never even set foot in Louisiana. In the heart of the most progressive and creative cultural city in America, why should we continue to commemorate this legacy?"[13][14]

Contrary to assertions that Robert E. Lee never set foot in New Orleans, he visited or passed through the city in 1846, 1848, 1860 and 1861, while serving in the United States Army.[15][16] While in New Orleans, Lee was quartered at the military post of Jackson Barracks.[17]

On December 17, 2015, the New Orleans City Council voted to relocate four statues from public display, among them the statue of Robert E. Lee located in Lee Circle.[18][19] Four organizations immediately filed a lawsuit[20] in federal court the day of the decision and the city administration agreed that no monument removals would take place before a court hearing scheduled for January 14, 2016.[21]

In January 2016, David Mahler, a contractor who had been hired by the City of New Orleans to remove the four statues, including the statue of Robert E. Lee located in Lee Circle, backed out of his contract with the city after he, his family, and employees began receiving death threats.[22][23] According to authorities in Baton Rouge, early on the morning of January 19, 2016, the Fire Department found a 2014 Lamborghini Huracán ablaze in a parking lot behind David Mahler's company, H&O Investments, LLC. The car, belonging to Mahler and valued at $200,000, was completely destroyed.[24][25]

On March 4, 2016, State Senator Beth Mizell, of Franklinton in Washington Parish, filed a bill in the Legislature seeking to block local governments in Louisiana from removing Confederate monuments and other commemorative statues without State permission.[26] The Mizell bill was unexpectedly assigned by Senate President John Alario, a Republican from Westwego in Jefferson Parish, to the Senate Governmental Affairs Committee, rather than to the Senate Education Committee. This doomed the bill; five of the nine members of the Governmental Affairs Committee were African-American Democrats, and it was chaired by Karen Carter Peterson of New Orleans. The Education Committee was composed of six Republicans and two Democrats.[27]

2016–17 legal developments

[edit]On March 25, 2016, a three-judge panel of the United States 5th Circuit Court of Appeals unanimously issued an injunction for the suit brought by the Monumental Task Committee and other groups in federal district court, prohibiting the City of New Orleans from proceeding forward with removal of the three Confederate monuments. The Court of Appeals set a hearing date of September 28, 2016, for oral argument for whether its injunction should be maintained pending a final judgment on the merits of the district court suit.[28] The decision of the Court of Appeals superseded that ruling of United States District Court Judge Carl Barbier rendered January 26, 2016, denying the motion of the plaintiffs for a preliminary injunction against the City of New Orleans for prohibiting removal of the monuments.[29][30]

On April 6, 2016, Senate Bill 276 by State Sen. Beth Mizell, R-Franklinton, to block local governments in Louisiana from removing Confederate monuments and other commemorative statues without State permission[31] was rejected by the Governmental Affairs Committee on a 5–4 racial and party line vote.[32] On August 14, 2016, pro-monuments House Bill 944 by Rep. Thomas Carmody, R-Shreveport, to create a state board with the power to grant or deny proposals to remove or relocate a statue, monument, memorial or plaque that has been on public property for more than 30 years died in the Municipal Affairs Committee after a 7–7 tie vote.[33][34][35]

On March 6, 2017, following oral argument on September 28, 2016 of the motion for preliminary injunction of the Monumental Task Committee and other groups opposed to removal of the Confederate monuments, the three-judge panel of the United States Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals issued its opinion unanimously deciding the City of New Orleans should be enjoined no further and could proceed forward with removal of the three monuments. In support of its ruling the Court of Appeals panel held, "we have exhaustively reviewed the record and can find no evidence in the record suggesting that any party other than the City has ownership" and the plaintiffs failed to show any irreparable harm would occur to the monuments if the City of New Orleans were to remove them, even assuming such evidence would constitute a harm to the groups bringing the suit.[36]

Dismantling

[edit]

On May 18, 2017, the City of New Orleans announced the statue of General Robert E. Lee would be removed the next day.[37][38] On May 19, 2017, following a day long effort by work crews, just after 6 o'clock p.m. the statue of Lee was finally detached and then removed and lowered by crane from its column pedestal to a semi-trailer truck and transported to storage.[39][40][41]

While crews were working on removing the statue, New Orleans mayor Mitch Landrieu gave a speech at Gallier Hall discussing the historical context of the Lee and other monuments, and the reasons for and meaning of their removal.[42]

The removal prompted Mississippi lawmaker Karl Oliver to post on Facebook that those supporting the take-down of the Confederate monuments "should be LYNCHED". He later apologized for this statement.[43][44]

See also

[edit]- Lee Circle

- List of memorials to Robert E. Lee

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Orleans Parish, Louisiana

- Jefferson Davis Monument (New Orleans, Louisiana)

- General Beauregard Equestrian Statue

- Removal of Confederate monuments and memorials

References

[edit]- ^ a b "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. April 15, 2008.

- ^ McConnaughey, Janet; Santana, Rebecca (May 19, 2017). "Robert E. Lee statue is last Confederate monument moved in New Orleans". Chicago Tribune. Associated Press. Retrieved May 20, 2017.

- ^ Charles Erasmus Fenner (1834-1911) Archived September 23, 2010, at the Wayback Machine in the Louisiana Historical Association's Dictionary of Louisiana Biography, retrieved April 20, 2018.

- ^ Wilson, Jr., Samuel; Lemann, Bernard (1971). "Architectural Inventory". New Orleans Architecture, Volume I: The Lower Garden District. Gretna, LA: Friends of the Cabildo and Pelican Publishing Company. p. 145. ISBN 9781455609321.

Lee Monument, Lee Circle.

- ^ Chatelain, Neil. "Lee's Circle". New Orleans Historical. University of New Orleans History Department; Tulane University Communication Department. Archived from the original on March 28, 2015. Retrieved July 11, 2015.

- ^ Rainey, Richard (May 19, 2017). "There's a staircase under the Robert E. Lee statue?". The Times-Picayune. New Orleans, LA. Retrieved May 19, 2017. Schematic of site

- ^ "Louisiana's Civil War Museum". New Orleans Official Guide. Retrieved July 7, 2015.

- ^ Karst, James (May 14, 2017). "The leaning tower of Lee: statue of Confederate general was encircled in controversy in 1953". The Times-Picayune. New Orleans, LA. Retrieved May 23, 2017.

- ^ "Robert E. Lee Monument". National Register of Historic Places Database (Louisiana). State of Louisiana, Office of Cultural Development, Division of Historic Preservation. Archived from the original on July 15, 2015. Retrieved July 12, 2015.. Listing includes 3 photographs, map, and details of site's historic significance as exemplar of the Lost Cause of the Confederacy, as conveyed in NRHP nomination

- ^ "The New Orleans Art Trail: 11 Important Statues". New Orleans. May 27, 2011. Retrieved September 22, 2015.

- ^ McClendon, Robert (June 24, 2015). "Mitch Landrieu on Confederate landmarks: 'That's what museums are for'". The Times-Picayune. Retrieved July 9, 2015.

Landrieu recalled Marsalis saying. When the mayor asked why, Marsalis responded, "Let me help you see it through my eyes. Who is he? What does he represent? And in that most prominent space in the city of New Orleans, does that space reflect who we were, who we want to be or who we are?"

- ^ Schachar, Natalie (August 15, 2015). "Jindal seeks to block removal of Confederate monuments in New Orleans". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 17, 2015.

- ^ "Why New Orleans should take down Robert E. Lee's statue: Wynton Marsalis". The Times-Picayune. December 15, 2015. Retrieved December 21, 2015.

- ^ Weiss, Debra Cassans. "Removal of Confederate monuments violates free-speech right to preserve history, suit says". abajournal. American Bar Association. Retrieved December 21, 2015.

- ^ Encyclopediavirginia.org

- ^ Thomas, Emory M. (1997) Robert E. Lee: A Biography. New York: W. W. Norton & Co. p. 426.

- ^ Geauxguardmuseums.com

- ^ Rainey, Richard (December 17, 2015). "Lee Circle no more: New Orleans to remove 4 Confederate statues". The Times-Picayune. Retrieved December 17, 2015.

- ^ Adelson, Jeff (December 17, 2015). "New Orleans City Council votes 6-1 to remove Confederate monuments". The New Orleans Advocate. Retrieved December 17, 2015.

- ^ "No. 2:15-cv-06905-CJB-DEK" (PDF). E.D. La. December 17, 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 18, 2015. Plaintiffs: Monumental Task Committee, Inc., Louisiana Landmarks Society, Foundation for Historical Louisiana, Inc., and Beauregard Camp, No. 130, Inc.

- ^ Katherine, Sayre (December 18, 2015). "New Orleans won't remove Confederate statues before court hearing". The Times-Picayune. Retrieved December 19, 2015.

- ^ "Baton Rouge contractor receives death threats, backs out of NOLA monument removal". WAFB. January 14, 2017. Retrieved May 22, 2017.

- ^ Williams, Jessica (January 15, 2017). "'Death threats,' 'threatening calls' prompt firm tasked with removing Confederate monuments to quit". The Advocate. Retrieved May 22, 2017.

- ^ "Man Hired To Remove Confederate Monuments In New Orleans Has $200,000 Lamborghini Torched". The Huffington Post. January 20, 2016. Retrieved April 5, 2017.

- ^ Ng, Alfred (January 20, 2017). "Louisiana contractor's $200,000 Lamborghini burned down after backing out of bid to remove Confederate monuments from New Orleans". New York Daily News. Retrieved May 22, 2017.

- ^ "Bill filed in Legislature to prevent takedowns of Confederate monuments | State Politics". Theadvocate.com. March 8, 2016. Retrieved April 5, 2017.

- ^ "Looks Like Beth Mizell's Monument-Protection Bill Is Dead, For Now". thehayride.com. March 30, 2016. Retrieved April 2, 2016.

- ^ "City must leave Confederate monuments in place while case is appealed, 5th U.S. Circuit Court rules | State Politics". Theadvocate.com. March 28, 2016. Retrieved April 5, 2017.

- ^ "Federal judge allows New Orleans to proceed with Confederate monument removal". Nola.com. Retrieved April 5, 2017.

- ^ Monumental Task Committiee, Inc. v. Foxx, 157 F.Supp.3d 573 (E.D.La., 2016)

- ^ Julia O'Donoghue (March 30, 2016). "Confederate monuments debate delayed in Louisiana Legislature". NOLA.com. Retrieved April 5, 2017.

- ^ Trimble, Megan (April 6, 2016). "Bill to block removal of Confederate monuments rejected". Associated Press. Retrieved December 24, 2018.

- ^ "Bill to stop removal Confederate monuments dies in state House". Wwltv.com. April 14, 2016. Retrieved April 5, 2017.

- ^ "Bill to block removal of New Orleans Confederate monuments fails in House panel; now what? | Legislature". Theadvocate.com. April 19, 2016. Retrieved April 5, 2017.

- ^ "Tie vote stalls bill to protect Confederate monuments". SunHerald. April 14, 2016. Retrieved April 5, 2017.

- ^ Monumental Task Committee, Inc. v. Chao, No. 16-30107. (5th Cir., 2017)

- ^ "All signs point to removal of New Orleans' Robert e. Lee statue imminent". May 18, 2017.

- ^ MacCash, Doug (May 18, 2017). "Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee statue coming down Friday morning, city announces". The Times-Picayune. New Orleans, LA. Retrieved May 19, 2017.

- ^ Nola.com

- ^ The Advocate

- ^ Robertson, Campbell (May 19, 2017). "From Lofty Perch, New Orleans Monument to Confederacy Comes Down". The New York Times. Retrieved May 20, 2017.

- ^ Sayre, Katherine (May 22, 2017). "Read Mayor Mitch Landrieu's speech on removing New Orleans' Confederate monuments". The Times-Picayune. Retrieved May 23, 2017.

- ^ Pilkington, Ed (May 22, 2017). "Mississippi lawmaker calls for lynchings after removal of Confederate symbols". The Guardian. Retrieved May 22, 2017.

- ^ Pettus, Emily Wagster (May 22, 2017). "Mississippi lawmaker apologizes for calling for lynching". The Washington Post. Associated Press. Archived from the original on May 22, 2017. Retrieved May 22, 2017.

Further reading

[edit]- "The Lee Monument. An Account of the Labors, etc". New Orleans, Louisiana: The Daily Picayune. February 22, 1884. Retrieved July 12, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- "The Lee Monument. The Inauguration, etc". New Orleans, Louisiana: The Daily Picayune. February 23, 1884. Retrieved July 13, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- Brock, R. A., ed. (1886). "Ceremonies Connected with the Unveiling of the Statue of General Robert E. Lee at Lee Circle, New Orleans, February 22, 1884". Southern Historical Society Papers. Vol. 14. Southern Historical Society. pp. 62–96.

- Brock, R. A., ed. (1886). "Historical Sketch of the R.E. Lee Monumental Association of New Orleans". Southern Historical Society Papers. Vol. 14. Southern Historical Society. pp. 96–99.

- 1884 establishments in Louisiana

- 1884 sculptures

- Bronze sculptures in Louisiana

- Buildings and structures in New Orleans

- Confederate States of America monuments and memorials in Louisiana

- Monuments and memorials on the National Register of Historic Places in Louisiana

- National Register of Historic Places in New Orleans

- Outdoor sculptures in Louisiana

- Statues of Robert E. Lee

- Relocated buildings and structures in Louisiana

- Removed Confederate States of America monuments and memorials