Apartment Zero

This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2017) |

| Apartment Zero | |

|---|---|

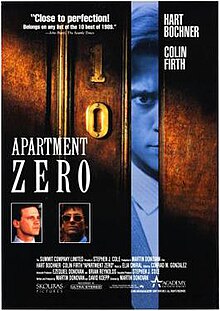

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Martin Donovan |

| Screenplay by | Martin Donovan David Koepp |

| Story by | Martin Donovan |

| Produced by | Martin Donovan David Koepp |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Miguel Rodríguez |

| Edited by | Conrad M. Gonzalez |

| Music by | Elia Cmíral |

Production companies | Producers Representative Organization The Summit Company |

| Distributed by | Union Station Media (US) |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 124 minutes (theatrical release & 2007 DVD release) 116 minutes (TV Version) |

| Countries | United Kingdom Argentina |

| Languages | English Spanish |

| Box office | $1,267,578 |

Apartment Zero, also known as Conviviendo con la muerte (Spanish: Living with Death),[1] is a 1988 British-Argentine[1] psychological-political thriller film directed by Argentine-born screenwriter Martin Donovan, co-written by Donovan and David Koepp and starring Hart Bochner and Colin Firth. It was produced in 1988 and premiered at film festivals throughout the next year. The story is set in a rundown area of Buenos Aires at the dawn of the 1980s, where Adrian LeDuc becomes friends with Jack Carney, an American expatriate who rents a room from him. Gradually, Adrian begins to suspect that the outwardly likeable Jack is responsible for a series of political assassinations that are rocking the city.

Famously suffused with homoerotic overtones and moments of black comedy,[2] it received mixed-to-positive reviews at the time of its release, and currently has a Rotten Tomatoes' score of 75% positive reactions from both critics and viewers.[3]

Plot

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2019) |

Adrian LeDuc (Firth) is the British owner of a revival house in Buenos Aires. Apart from his mother, the core of his emotional life is movies, specifically classic American movies and stars. The story begins with Adrian in his theater, watching the final scene of Touch of Evil.

As his theater loses more and more money, Adrian advertises for a roommate to share his apartment rent. After several unsatisfactory applicants, he meets American Jack Carney (Bochner), who agrees to take the room. The shy, repressed Adrian is both intimidated by and attracted to Jack, who exudes confidence and strength, and attempts to win Jack's trust and companionship. Jack seems to suspect this and doesn't mind, and he takes a liking to his new landlord.

Jack befriends some of the neighbors. Adrian complains to Jack, telling him that the neighbors aren't to be trusted. Despite Adrian's jealousy, Jack continues to socialize with several of them, becoming sexually involved with Laura, whose husband is frequently away. Claudia, the ticket seller at Adrian's cinema, is involved with a political committee investigating a series of murders that bear a striking resemblance to those committed by members of death squads that operated in Argentina during its last civil-military dictatorship (1976–1983).

Adrian learns that Jack has been lying about his employment and becomes paranoid that Jack is spying on him. He searches Jack's room and finds a number of photographs of Jack in paramilitary garb. Jack returns and calms a highly agitated Adrian, but his own suspicions are aroused when he realizes that Adrian has been in his room.

Though he's personally apolitical, Adrian allows Claudia's committee to use his theatre to view footage of death squad members. Adrian is horrified to see the same sign in the film as appeared in some of the photos of Jack he'd found earlier. Jack, realizing that Adrian is growing more suspicious, falsifies Adrian's passport and prepares to leave Argentina. Unfortunately, the passport is expired and he can't leave. Jack picks up a young gay man and murders him for his passport—but then makes a hash of trying to paste his own photos into the dead man's passport.

Meanwhile, Adrian is devastated by the death of his mother. Adrian gets drunk and creates a disturbance in his apartment, concerning his neighbors. The following morning a television report of the murder of a young man leads the neighbors to think that Adrian has done something to Jack. That evening, the neighbors confront Adrian, forcing their way into his apartment and physically attacking him. Jack returns and tends to the badly injured Adrian.

As Adrian attends his mother's funeral, Claudia comes to the apartment and recognizes Jack from the death squad photos. Adrian returns to find Claudia dead at Jack's hands. A clearly unhinged Adrian, who is as terrified of losing Jack as he is horrified by Claudia's murder, helps Jack dispose of the body. On the way out they run into Laura and her husband. Looking for an alibi, Jack says he's leaving for California in the morning.

After they dump the body in a garbage landfill outside the city, Adrian suggests they really go to California together and Jack agrees. Back at the apartment Adrian changes his mind and goes for Jack's gun in the living room. Jack realizes what's happening and begins strangling Adrian, but eventually lets him up. Adrian again goes for the gun and he and Jack struggle. With the gun pointed at him and with Adrian's finger on the trigger, Jack says "Do it" and the gun goes off.

Some days after, Adrian is having dinner when Laura comes to the door, seeking Jack's address in California. Adrian says he hasn't heard from him and shuts the door. He returns to the table and pours two glasses of wine, one for himself and one for Jack's corpse, which he has kept and sat at the table. The final scene shows a large crowd outside Adrian's cinema, which is now a porn theater. Adrian, who has never gone out in public without a suit and tie, stands in the building's doorway wearing a T-shirt and Jack's black leather jacket, while smoking a cigarette—all just as Jack used to do.

Cast

[edit]- Hart Bochner – Jack Carney

- Colin Firth – Adrian LeDuc

- Dora Bryan – Margaret McKinney

- Liz Smith – Mary Louise McKinney

- Fabrizio Bentivoglio – Carlos Sanchez-Verne

- James Telfer – Vanessa

- Mirella D'Angelo – Laura Werpachowsky

- Juan Vitali – Alberto Werpachowsky

- Cipe Lincovsky – Mrs. Treniev

- Francesca d'Aloja – Claudia

- Miguel Ligero – Mr. Palma

- Elvia Andreoli – Adrian's Mother

- Marikena Monti – Tango Singer

- Luis Romero – Projectionist

- Max Berliner – Prospective Tenant

- Debora Bianco – Girl in Cafe

- Federico D'Elía – Boy in Cafe

- Raúl Florido – Jack's Argentine Contact

- Claudio Ciacci – Young Man in Cinema

- Gabriel Posniak – Dead Man

- Darwin Sanchez – Police Inspector

- Daniel Queirolo – Young Cop

- Miguel Ángel Porro – Taxi Driver

- Ezequiel Donovan – Foreign Element

- Eduardo Peralta Ramos – Foreign Element

- John Kamps – Foreign Element

- Göran Johansson – Foreign Element

- Lisanne Cole – Political Group in Cinema

- Germán Palacios – Member of Political Group in Cinema

- Horacio Erman – Political Group in Cinema

- Inés Estévez – Political Group in Cinema

- Gabriel Corrado – Victim in Apartment

Themes

[edit]The doppelgänger or double is a recurring motif of Apartment Zero.[4][5] Adrian and Jack bear some physical resemblance (which Jack planned to exploit to escape the country). A character comments that Jack is a double of someone from his past. Jack and "Michael Weller" are a doubled pair, as are Jack and the murdered gay man. By film's end, instead of Jack becoming Adrian, Adrian instead has become Jack.

Another motif is classic films, especially films which have some connection to gay culture.[6][7] Adrian runs a revival house. He and Jack play a movie trivia game together frequently.[8] Adrian's apartment is decorated with framed portraits of movie stars, including a number who were, or are perceived as being, gay or bisexual (including James Dean and Montgomery Clift). Adrian's choice of films also reflects a gay interest, including a Dean film festival and Compulsion, based on the Leopold and Loeb murder case.[9]

Historical and political context

[edit]The setting of the film ties its characters to the political situation in Argentina in the early 1980s. The main events transpire shortly after the end of Argentina's last civil-military dictatorship (1976-1983); the regime (self-titled as National Reorganization Process) imposed a political climate of state-sponsored terrorism, and the period was marred by widespread human rights violations.[10][11] The state-sponsored terrorism of the military Junta created a climate of violence whose victims were in the thousands and included left-wing activists and militants, intellectuals and artists, trade unionists, High School and College/University students and journalists, as well as Marxists, Peronist guerrillas or alleged sympathizers of both.[2]

Although in the period there was leftist violence involved,[12][13] mostly by the Montoneros guerrilla,[14] most of the victims were unarmed non-combatants, and the guerrillas were exterminated by 1979, while the dictatorship carried out its crimes until the exit from power.[15][16] After the defeat in the Falklands War, the Junta called for elections in 1983. The National Commission on the Disappearance of Persons originally estimated that around 13,000 individuals were disappeared.[17] Present estimates for the number of people who were killed or disappeared range from 9,089 to over 30,000;[18][19] The military themselves reported killing 22,000 people in a 1978 communication to Chilean Intelligence,[20] and the Mothers and Grandmothers of the Plaza de Mayo, which are the most important Human-Rights Organisations in Argentina, have always jointly maintained that the number of disappeared is unequivocally 30,000.[21] Since 1983 Argentina has maintained democracy as its ruling system.

Reception

[edit]Reviews

[edit]Apartment Zero received a 75% rating on Rotten Tomatoes from a sample of 32 reviews.[22]

Critics were sharply divided on the film. Most of the reviews were negative, although the performances of Bochner and particularly Firth were widely praised.[citation needed]

Vincent Canby of The New York Times called the film "hilariously awful", and stated, "A good deal of money has been spent on this nonsense, which was shot in Buenos Aires in English. It pretends to be a psychological-political melodrama but plays like the work of a dilettante; that is, the work of someone who wants to make movies, has the means to make them, but doesn't, as yet, know what he wants to make them about."[23] Writing for the Chicago Tribune, Dave Kehr called the film "A definite oddity, though not an entirely compelling one ... turns what might have been a modestly successful psychological thriller into a messily failed art film."[24] Kevin Thomas's review in the Los Angeles Times lead with "Zero Doesn't Add Up as a Thriller", adding "Nothing, however, makes much sense right from the start. Unfortunately, the long-winded Apartment Zero is awkward to the point of ludicrousness."[25] Roger Ebert called the film "lurid and overwrought, almost a self-parody".[26]

Awards and nominations

[edit]- Cognac Festival du Film Policier Critics Award winner and Special Jury Prize – Martin Donovan (1990)

- Seattle International Film Festival Golden Space Needle Award for Best Film (1989)

- Sundance Film Festival Grand Jury Prize (Dramatic) nomination (1989)

References

[edit]- ^ a b Conviviendo con la muerte (Apartment Zero) Cinenacional.com

- ^ a b 'Apartment Zero' (R), by Rita Kempley 11 April 1989, The Washington Post

- ^ "Apartment Zero". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

- ^ "Apartment Zero (1988)". www.popmatters.com. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- ^ "Apartment Zero". www.culturecourt.com. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- ^ Kaminsky, Amy K. (2008). Argentina: Stories for a Nation. U of Minnesota Press. p. 192. ISBN 9780816649488.

adrian "apartment zero" lgbt gay.

- ^ "Apartment Zero (1988)". Moria. 1 May 1999. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- ^ "The Studly American [Apartment Zero] | Jonathan Rosenbaum". www.jonathanrosenbaum.net. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- ^ "Apartment Zero (1988)". www.popmatters.com. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- ^ CONADEP, Nunca Más Report, Chapter II, Section One:Advertencia, [1] (in Spanish)

- ^ Atrocities in Argentina (1976–1983) Holocaust Museum Houston

- ^ "Bombing of Police Station In Argentina Kills 3". The New York Times. 29 January 1977.

- ^ "Crowded city bus bombed". The Gadsden Times. 19 February 1977 – via Google News.

- ^ Cecilia Menjívar & Néstor Rodriguez (21 July 2009). When States Kill: Latin America, the U.S., and Technologies of Terror. University of Texas Press, 2005. p. 317. ISBN 9780292778504.

- ^ "Argentina: In Search of the Disappeared" Time. 24 September 1979. - Amnesty International reported in 1979 that 15,000 disappeared had been abducted, tortured and possibly killed.

- ^ "Banker murdered by gang". The Spokesman-Review. 9 November 1979 – via news.google.com.

- ^ Una duda histórica: no se sabe cuántos son los desaparecidos. Clarin.com. 06/10/2003.

- ^ Obituary The Guardian, Thursday 2 April 2009

- ^ Daniels, Alfonso. (17 May 2008) "Argentina's dirty war: the museum of horrors". Telegraph. Retrieved on 6 August 2010.

- ^ The Army admitted 22,000 crimes, by Hugo Alconada Mon 24 March 2006, La Nación (in Spanish)

- ^ 40 years later, the mothers of Argentina's 'disappeared' refuse to be silent, by Uki Goñi 28 April 2017, The Guardian

- ^ "Apartment Zero". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 10 May 2023.

- ^ Canby, Vincent (18 October 1989). "'Apartment Zero' and Its Strange Tenant". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 13 September 2018. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- ^ Kehr, Dave (22 January 1990). "Thriller Gone Bad". Archived from the original on 13 September 2018. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- ^ Thomas, Kevin (20 October 1989). "Movie Review: 'Zero' Doesn't Add Up as a Thriller". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 2 December 2017. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- ^ "Bad Influence movie review & film summary (1990) | Roger Ebert".

External links

[edit]- 1988 films

- 1988 LGBT-related films

- 1980s psychological thriller films

- Dirty War films

- Films produced by David Koepp

- Films scored by Elia Cmíral

- Films set in apartment buildings

- Films set in Argentina

- Films set in a movie theatre

- Films shot in Buenos Aires

- British political thriller films

- Films with screenplays by David Koepp

- 1980s Spanish-language films

- British neo-noir films

- Bisexuality-related films

- Films directed by Martin Donovan (screenwriter)

- 1980s English-language films

- English-language Argentine films

- 1988 multilingual films

- British multilingual films

- 1980s British films

- British LGBT-related films

- Argentine LGBT-related films

- Argentine thriller films