Armenian diaspora

| Part of a series on |

| Armenians |

|---|

|

| Armenian culture |

| By country or region |

Armenian diaspora Russia |

| Subgroups |

| Religion |

| Languages and dialects |

|

| Persecution |

The Armenian diaspora refers to the communities of Armenians outside Armenia and other locations where Armenians are considered an indigenous population. Since antiquity, Armenians have established communities in many regions throughout the world. However, the modern Armenian diaspora was largely formed as a result of World War I, when the genocide which was committed by the Ottoman Empire forced Armenians who were living in their homeland to flee from it or risk being killed.[1][2] Another wave of emigration started during the dissolution of the Soviet Union.[3]

The High Commissioner for Diaspora Affairs established in 2019 is in charge of coordinating and developing Armenia's relations with the diaspora.

Terminology

[edit]In Armenian, the diaspora is referred to as spyurk (pronounced [spʰʏrkʰ]), spelled սփիւռք in classical orthography and սփյուռք in reformed orthography.[4][5] In the past, the word gaghut (գաղութ pronounced [ɡɑˈʁutʰ]) was used mostly to refer to the Armenian communities outside the Armenian homeland. It is borrowed from the Aramaic (Classical Syriac) cognate[6] of Hebrew galut (גלות).[7][8]

History

[edit]The Armenian diaspora has been present for over 1,700 years.[9] The modern Armenian diaspora was largely formed after World War I as a result of the Armenian genocide. According to Randall Hansen, "Both in the past and today, the Armenian communities around the world have developed in significantly different ways within the constraints and opportunities found in varied host cultures and countries."[1]

In the fourth century, Armenian communities already existed outside Greater Armenia. Diasporic Armenian communities emerged in the Achaemenid and Sassanid empires, and they also defended the eastern and northern borders of the Byzantine Empire.[10] In order to populate the less populated areas of Byzantium, Armenians were relocated to those regions. Some Armenians converted to Greek Orthodoxy while retaining Armenian as their primary language, whereas others remained in the Armenian Apostolic Church despite pressure from official authorities. A growing number of Armenians migrated to Cilicia during the course of the eleventh and twelfth centuries as a result of the Seljuk Turk invasions. After the fall of the kingdom to the Mamelukes and loss of Armenian statehood in 1375, up to 150,000 went to Cyprus, the Balkans, and Italy.[10] Although an Armenian diaspora existed during Antiquity and the Middle Ages, it grew in size due to emigration from the Ottoman Empire, Iran, Russia, and the Caucasus.

The Armenian diaspora is divided into two communities – those communities from Ottoman Armenia (or Western Armenia) and those communities which are from the former Soviet Union, independent Armenia and Iran (or Eastern Armenia).

Armenians in Turkey, such as Hrant Dink, do not consider themselves a part of the Armenian Diaspora, since they have been living in their historical homeland for more than four thousand years.[11][12] They are not considered part of the diaspora either by the Ministry of Diaspora Hranush Hakobyan: "Diaspora represents all the Armenians who live beyond the Armenian Highland. In this context, we have singled out the Armenians of Istanbul and those living on the territory of Western Armenia. Those people have inhabited the lands for thousands of years, and they are not considered Diaspora [representatives]."[13]

Before 1870, 60 Armenian immigrants settled in New England.[14] Armenian immigration rose to 1,500 by the end of the 1880s, and rose to 2,500 in the mid-1890s due to massacres caused by the Ottoman Empire. Armenians who immigrated to the United States before WWI were primarily from Asia Minor and settled on the East Coast.[14]

The Armenian diaspora grew considerably both during and after the First World War due to the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire.[15] In the year 1910, over 5,500 Armenians immigrated to the United States, and by 1913, 9,355 more Armenians entered the North American borders.[14] As World War I approached, the rate of Armenian immigration rose to about 60,000. In 1920 and until the Immigration Act of 1924, 30,771 Armenians came to the United States; the immigrants were predominantly widowed women, children, and orphans.[14] Although many Armenians perished during the Armenian genocide, some of the Armenians who managed to escape, established themselves in various parts of the world.

By 1966, around 40 years after the start of the Armenian genocide, 2 million Armenians still lived in Armenia, while 330,000 Armenians lived in Russia, and 450,000 Armenians lived in the United States and Canada.[16]

In the United States, the rate of immigration increased after the Immigration Act was passed in 1965.[14] The outbreak of the civil War in Lebanon in 1975 and the outbreak of the Islamic Revolution in Iran during 1978 were factors which pushed Armenians to immigrate. The 1980 U.S. Census reported that 90 percent of the immigration to the United States was undertaken by Iranian-Armenians during the years from 1975 and 1980.[14]

Distribution

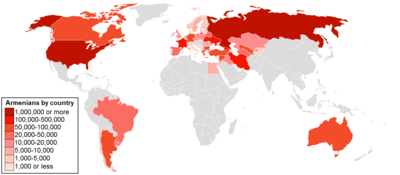

[edit]Less than one third of the world's Armenian population lives in Armenia. Their pre-World War I population area was six times larger than that of present-day Armenia, including the eastern regions of Turkey, northern part of Iran, and the southern part of Georgia.[17]

By 2000, there were 7,580,000 Armenians living abroad in total.[16]

See also

[edit]- Armenia–Azerbaijan relations

- Armenia–European Union relations

- Armenia–Russia relations

- Armenia–Turkey relations

- Armenia–United States relations

- Foreign relations of Armenia

- Largest Armenian diaspora communities

- List of diasporas

- Office of the High Commissioner for Diaspora Affairs

- Visa requirements for Armenian citizens

- White genocide (Armenians)

Sources

[edit]- Ayvazyan, Hovhannes (2003). Հայ Սփյուռք հանրագիտարան [Encyclopedia of Armenian Diaspora] (in Armenian). Vol. 1. Yerevan: Armenian Encyclopedia publishing. ISBN 5-89700-020-4.

- de Waal, Thomas (2003). Black Garden: Armenia and Azerbaijan Through Peace and War. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-1945-9.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Hansen, Randall. Immigration and asylum: from 1900 to the present. p. 13.

- ^ Lewis, Martin W. (2015-05-27). "The Armenian Diaspora Is An Ongoing Phenomenon". In Berlatsky, Noah (ed.). The Armenian Genocide. Greenhaven Publishing LLC. pp. 66–72. ISBN 978-0-7377-7319-4.

- ^ "Diaspora - Armenian Diaspora Communities". diaspora.gov.am. Retrieved 2021-11-04.

- ^ Dufoix, Stéphane (2008). Diasporas. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. p. 84. ISBN 978-0-520-25359-9.

- ^ Harutyunyan, Arus (2009). Contesting National Identities in an Ethnically Homogeneous State: The Case of Armenian Democratization. Western Michigan University. p. 56. ISBN 978-1-109-12012-7.

- ^ Ačaṙean, Hračʿeay (1971–1979). Hayerēn Armatakan Baṙaran [Dictionary of Armenian Root Words]. Vol. 1. Yerevan: Yerevan University Press. p. 505.

- ^ Melvin Ember; Carol R. Ember; Ian A. Skoggard (2004). Encyclopedia of diasporas: immigrant and refugee cultures around the world. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-306-48321-9.

- ^ Diaspora: Volume 1, Issue 1. Oxford University Press. 1991. ISBN 978-0-19-507081-1.

- ^ Herzig, Edmund (2004-12-10). The Armenians: Past and Present in the Making of National Identity. Taylor & Francis. p. 126. ISBN 9780203004937.

- ^ a b Ember, Melvin; Ember, Carol R.; Skoggard, Ian (2004). Encyclopedia of Diasporas: Immigrant and Refugee Cultures around the World. Springer. pp. 36–43. ISBN 0-306-48321-1.

- ^ Baronian, Marie-Aude; Besser, Stephan; Jansen, Yolande (2006-01-01). Diaspora and Memory: Figures of Displacement in Contemporary Literature, Arts and Politics. BRILL. doi:10.1163/9789401203807_006. ISBN 978-94-012-0380-7.

- ^ Baser, Bahar; Swain, Ashok (2009). "Diaspora Design Versus Homeland Realities: Case Study of Armenian Diaspora". Caucasian Review of International Affairs: 57.

- ^ "Minister denies calling Armenians 'Diaspora representatives' in Istanbul". www.tert.am. Retrieved 2023-10-08.

- ^ a b c d e f Bakalian, Anny P. (1993). Armenian-Americans : from being to feeling Armenian. New Brunswick (U.S.A.): Transaction Publishers. ISBN 1-56000-025-2. OCLC 24538802.

- ^ Harutyunyan, Arus (April 2009). Contesting National Identities in an Ethnically Homogeneous State: The Case of Armenian Democratization (PhD thesis). Western Michigan University.

- ^ a b Cohen, Robin (2010). Global Diasporas: An Introduction. Routledge. pp. 48–63.

- ^ Melvin Ember; Carol R. Ember; Ian A. Skoggard (2004). Encyclopedia of diasporas: immigrant and refugee cultures around the world. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-306-48321-9.

Currently, only one-sixth of that land [ancestral territory] is inhabited by Armenians, due first to variously coerced emigrations and finally to the genocide of the Armenian inhabitants of the Ottoman Turkish Empire in 1915.

External links

[edit]- Office of the High Commissioner for Diaspora Affairs

- Ovenk.com, Armenian Diaspora Memory and Innovation

- The Armenian Diaspora Today: Anthropological Perspectives. Articles in the Caucasus Anallytical Digest No. 29

- Neruzh Diaspora Tech Startup Program