Logan Square, Chicago

Logan Square | |

|---|---|

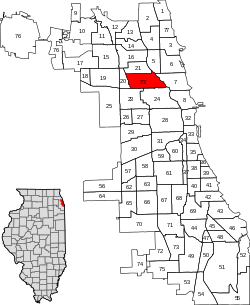

| Community Area 22 – Logan Square | |

Illinois Centennial Memorial in neighborhood namesake Logan Square | |

Location within the city of Chicago | |

| Coordinates: 41°55.7′N 87°42.4′W / 41.9283°N 87.7067°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Illinois |

| County | Cook |

| City | Chicago |

| Neighborhoods | |

| Area | |

| • Total | 3.23 sq mi (8.37 km2) |

| Population (2020)[1] | |

| • Total | 71,665 |

| • Density | 22,000/sq mi (8,600/km2) |

| Demographics (2020)[1] | |

| • White | 51.6% |

| • Black | 4.5% |

| • Hispanic | 36.3% |

| • Asian | 4.2% |

| • Other | 3.3% |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| ZIP Codes | parts of 60614, 60618, 60622, 60639, 60647 |

| Median household income (2020) | $84,653[1] |

| Source: Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning (CMAP) July 2022 Release | |

Logan Square is an official community area, historical neighborhood, and public square on the northwest side of the City of Chicago. The Logan Square community area is one of the 77 city-designated community areas established for planning purposes. The Logan Square neighborhood, located within the Logan Square community area, is centered on the public square that serves as its namesake, located at the three-way intersection of Milwaukee Avenue, Logan Boulevard and Kedzie Boulevard.

The community area of Logan Square is, in general, bounded by the Metra/Milwaukee District North Line railroad on the west, the North Branch of the Chicago River on the east, Diversey Parkway on the north, and the 606 (also known as the Bloomingdale Trail) on the south.[2] The area is characterized by the prominent historical boulevards, stately greystones and large bungalow-style homes.

History

[edit]

Name and Centennial Monument

[edit]Logan Square is named for General John A. Logan, an American soldier and political leader. The square itself is a large public green space (designed by architect William Le Baron Jenney, landscape architect Jens Jensen and others) formed as the grand northwest terminus of the Chicago Boulevard System and the junction of Kedzie and Logan Boulevards and Milwaukee Avenue. At the center of the square is the Illinois Centennial Monument, built in 1918 to commemorate the 100th anniversary of Illinois' statehood (geographic coordinates as shown above for this article). The monument, designed by Henry Bacon, famed architect of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C. and sculpted by Evelyn Beatrice Longman, is a single 70-foot (25-meter) tall "Tennessee-pink" marble Doric column, based upon the same proportions as the columns of the Parthenon in Ancient Greece, and topped by an eagle, in reference to the state flag and symbol of the state and the nation.[3] The monument was funded by the Benjamin Ferguson Fund.[4] Reliefs surrounding the base depict allegorical figures of Native Americans, explorers, Jesuit missionaries, farmers, and laborers intended to represent Illinois contributions to the nation through transportation as a railroad crossroads for passengers and freight (represented by a train extending across the arm of one of the figures), education, commerce, grain and commodities, religion and exploration, along with the "pioneering spirit" during the state's first century.

Development

[edit]Originally developed by early settlers like Martin Kimbell (of Kimball Avenue fame) in the 1830s, forming around the towns of "Jefferson," "Maplewood," and "Avondale', the vicinity was annexed into the city of Chicago in 1889 and renamed Logan Square. Many of its early residents were English or Scandinavian origin, mostly Norwegians and Danes, along with both a significant Polish and Jewish population that followed. Milwaukee Avenue, which spans the community, is one of the oldest roads in the area and remains both a cultural and commercial artery. The road traces its origins prior to 1830 as a Native American trail and became known as "Northwest Plank Road" when it was constructed with wooden boards in 1849. In 1892, a streetcar line was extended along Milwaukee Avenue and, in 1895, the electrified elevated rail line (today's Blue Line) was built alongside the road up to Logan Square itself, stimulating a new building boom. Milwaukee Avenue was finally paved in 1911 to accommodate motor cars. A baseball stadium at the corner of Milwaukee and Diversey hosted the Logan Square Baseball Club, which defeated both the Chicago Cubs and White Sox, who had just played each other in the crosstown 1906 World Series.[5]

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1930 | 114,174 | — | |

| 1940 | 110,010 | −3.6% | |

| 1950 | 106,763 | −3.0% | |

| 1960 | 94,799 | −11.2% | |

| 1970 | 88,462 | −6.7% | |

| 1980 | 84,768 | −4.2% | |

| 1990 | 82,605 | −2.6% | |

| 2000 | 82,685 | 0.1% | |

| 2010 | 73,595 | −11.0% | |

| 2020 | 71,665 | −2.6% | |

| [6] | |||

Present

[edit]Today, the neighborhood is home to a diverse population including an established Latino community (primarily Mexican and Puerto Rican, with some Cuban), a number of ethnicities from Eastern Europe (mostly Poles), and a growing number of Millennials, due to gentrification.[7][8] Additionally, the increase in housing costs in nearby Wicker Park, Lincoln Park, and the other Lakefront communities has led to many of Chicago's aspiring artists and restaurateurs to call Logan Square home. By 2000, gentrification had taken hold in Logan Square itself.[9] Residents are attracted to the community for its beautiful park-like boulevards, part of Chicago's 26-mile Chicago park and boulevard system. Known as the "Logan Square Boulevards District", the area was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1985 and became a protected Chicago Landmark in 2005. Additional development includes the partnerships between residents and the city to support the Comfort Station at Logan Square, new and renewed parks (See Palmer Square Park, below), the Bloomingdale Trail (an elevated "rails to trails" project), Logan Plaza, and sensitive developments (e.g. The Green Exchange and Chicago Printed String Building), along with the preservation of numerous historic buildings (historic commercial, industrial and residential structures) and several other important sustainable and green projects.

Churches

[edit]

Logan Square has many churches along its boulevards including Minnekirken, the historic Norwegian Lutheran Memorial Church located on the public square, and a meeting house of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints one block west. Just south of the square on Kedzie Avenue, Armitage Baptist Church is located in the former Masonic Temple, and to the east of the square on Logan Boulevard are the Episcopal Church of the Advent, a new Seventh-day Adventist Church and St. John Berchmans Catholic Church.

St. Luke's Lutheran Church of Logan Square, previously located just north of Logan Boulevard on Francisco Ave., sold their historic building in 2015 to New Community Covenant Church. St. Luke's now meets in the same building as Grace Methodist Church. Bucktown has three of the city's most noted Polish Cathedrals – the former All Saints Cathedral, St. Hedwig's in Chicago, and St. Mary of the Angels. On Fullerton just east of Milwaukee is a Christian Science church offering services in Spanish. On Ridgeway, just north of Fullerton, is Our Lady of Grace Catholic Church and School.

Palmer Square, a large rectangular-shaped historic public space and park which is also part of the Logan Square community, is home to St. Sylvester Catholic Church and School and the Serbian Orthodox Church of the Holy Resurrection. Also, Grace Methodist Church stands at the corner of Kimball and Wrightwood Avenues, as does a Spanish Pentecostal church, across the street.

Kimball Avenue Church,[10] whose 103-year-old building once stood at the corner of Kimball and Medill Avenues, continues to meet in Logan Square and has rehabilitated the land on which the church once stood into a corner garden. In 2015 the church began raising funds to use a portion of the land as the future site of a prayer labyrinth.

Neighborhoods

[edit]Belmont Gardens

[edit]Belmont Gardens spans the Chicago Community Areas of Logan Square and Avondale like neighboring Kosciuszko Park, located within its northwest portion, where the Pulaski Industrial Corridor abuts these residential areas. The boundaries of Belmont Gardens are generally held to be Pulaski Road to the East, the Union Pacific/Northwest rail line to the West, Belmont Avenue to the North, and Fullerton Avenue to the South.

Most of the land between Fullerton Avenue and Diversey Avenue as well as Kimball to the Union Pacific/Northwest rail line was empty as late as the 1880s, mostly consisting of the rural "truck farms" that peppered much of Jefferson Township. This began to change with the annexation of this rustic hinterland to the city in 1889 in anticipation of the World's Columbian Exposition that would focus the country's eyes on Chicago just a few years later in 1893.

Belmont Gardens' first urban development began thanks to Homer Pennock, who founded the industrial village of Pennock, Illinois. Centered on Wrightwood Avenue, which was originally laid out as "Pennock Boulevard", the area was planned to be a hefty industrial and residential district. The development was so renowned that the village was highlighted in a "History of Cook County, Illinois" authored by Weston Arthur Goodspee and Daniel David Healy.[11] Thwarted by circumstances as well as the decline of Homer Pennock's fortune, this district declined to the point that the Chicago Tribune wrote about the neighborhood in an article titled "A Deserted Village in Chicago"[12] in 1903. The original name of the Healy Metra Station was originally named after this now lost settlement.

While Homer Pennock's industrial suburb failed, Chicago's rapid expansion transformed the area's farms into clusters of factories and homes. At the turn of the 20th century as settlement was booming, Belmont Gardens and Avondale were at the northwestern edge of the Milwaukee Avenue Polish Corridor - a contiguous stretch of Polish settlement which spanned this thoroughfare all the way from the southern tip of Wicker Park's Polonia Triangle at the intersection of Milwaukee, Division Street and Ashland Avenue, north to Irving Park Road.

Belmont gardens offered more than just a less congested setting for its new residents. Due to its proximity to rail along the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul and Pacific Railroad, the area developed a plethora of industry that still survives in the city's Pulaski Industrial Corridor. It was adjacent to his own factory that Mr. Walter E. Olson built what the Chicago Tribune put at the top of its list of the "Seven Lost Wonders of Chicago",[13]

The Olson Park and Waterfall Complex, a 22-acre garden and waterfall remembered by Chicagoans citywide as the place they fondly reminisce heading out to for family trips on the weekend. The ambitious project took 200 workers more than six months to fashion it out of 800 tons of stone and 800 yards of soil.

Latino settlement in the neighborhood began in the 1980s. Today the area still retains its blue collar feel as much of surrounding Logan Square and Avondale undergo increased gentrification.

Bucktown

[edit]

Bucktown is a neighborhood located in the east of the Logan Square community area in Chicago, directly north of Wicker Park, and northwest of the Loop. Bucktown gets its name from the large number of goats raised in the neighborhood during the 19th century when it was an integral part of the city's famed Polish Downtown. The original Polish term for the neighborhood was Kozie Prery (Goat Prairie). Its boundaries are Fullerton Avenue to the north, Western Avenue to the west, Bloomingdale or North Avenue[14][15] to the south, and the Kennedy Expressway to the east. Bucktown's original boundaries were Fullerton Avenue, Damen Avenue (formerly Robey Street), Armitage Avenue and Western Avenue.

Bucktown is primarily residential, with a mix of older single family homes, new builds with edgy architecture, and converted industrial loft spaces. Horween Leather Company has been on North Elston Avenue in Bucktown since 1920.[16] The neighborhood's origins are rooted in the Polish working class, which first began to settle in the area in the 1830s.[17] A large influx of Germans began in 1848 and in 1854 led to the establishment of the town of Holstein, which was eventually annexed into Chicago in 1863. In the 1890s and 1900s, immigration from Poland, the annexation of Jefferson Township into Chicago and the completion of the Logan Square Branch of the Metropolitan Elevated Lines contributed to the rapid increase in Bucktown's population density. Three of the city's most opulent churches designed in the so-called "Polish Cathedral style" - St. Hedwig's, the former Cathedral of All Saints and St. Mary of the Angels - date from this era.

The early Polish settlers had originally designated many of Bucktown's streets with names significant to their people – Kosciusko, Sobieski, Pulaski and Leipzig (after the Battle of Leipzig). Chicago's City Council, prompted by a Bucktown-based German contingent with political clout, changed these Polish-sounding names in 1895 and 1913. In its place the new names for these thoroughfares bore a distinct Teutonic hue – Hamburg, Frankfort, Berlin and Holstein. Anti-German sentiment during World War I brought about another name-change that left today's very Anglo-Saxon sounding names: McLean, Shakespeare, Charleston, and Palmer.[17]

Polish immigration into the area accelerated during and after World War II when as many as 150,000 Poles are estimated to have arrived in Polish Downtown between 1939 and 1959 as Displaced Persons.[18] Like the Ukrainians in nearby Ukrainian Village, they clustered in established ethnic enclaves like this one that offered shops, restaurants, and banks where people spoke their language. Milwaukee Avenue was the anchor of the city's "Polish Corridor", a contiguous area of Polish settlement that extended from Polonia Triangle to Avondale's Polish Village. Additional population influxes into the area at this time included European Jews and Belarusians.

Latino migration to the area began in the 1960s with the arrival of Cuban, Puerto Rican, and later Mexican immigrants. Puerto Ricans in particular concentrated in the areas along Damen and Milwaukee Avenues through the 1980s after being displaced by the gentrification of Lincoln Park that started in the 1960s. The local Puerto Rican community lent heavy support for the Young Lords and other groups that participated in Harold Washington's victorious mayoral campaign. In the last quarter of the 20th century, a growing artists' community led directly to widespread gentrification, which brought in a large population of young professionals. In recent years, many trendy taverns and restaurants have opened in the neighborhood. There also have been a considerable number of "teardowns" of older housing stock, often followed by the construction of larger, upscale residential buildings.

Bucktown has a significant shopping district on Damen Avenue, extending north from North Avenue (in Wicker Park) to Webster Avenue. The neighborhood is readily accessible via the Blue Line and has multiple access points to the elevated Bloomingdale Trail, also known as the 606.

Kosciuszko Park

[edit]

Kosciuszko Park (correctly pronounced "Ko-shchoosh-coe" in Polish) spans the Chicago Community Areas of Logan Square and Avondale like neighboring Belmont Gardens, located within its northwest portion, where the Pulaski Industrial Corridor abuts these residential areas. Colloquially known by locals as "Koz Park", or even the "Land of Koz",[19] the area is a prime example of a local identity born thanks to the green spaces created by Chicago's civic leaders of the Progressive Era.

The boundaries of Kosciuszko Park are generally held to be Central Park Avenue to the East, Pulaski Road to the West, George Street to the North, and Altgeld to the South.

Kosciuszko Park and Avondale were at the Northwestern edge of the Milwaukee Avenue "Polish Corridor"—a contiguous stretch of Polish settlement which spanned this thoroughfare all the way from Polonia Triangle at Milwaukee, Division and Ashland to Irving Park Road.

Adjacent to Kosciuszko Park's border with Avondale proper near the intersection of George Street and Lawndale Avenue is St. Hyacinth Basilica, which began in 1894 as a refuge for locals to tend to their spiritual needs. A shrine, St. Hyacinth's features relics associated with Pope John Paul II, as well as an icon with an ornate jeweled crown that was blessed by the late pontiff. Other institutions further enriched the institutional fabric of the Polish community in the area. In 1897, the Polish Franciscan Sisters began building an expansive complex on Schubert and Hamlin Avenues with the construction of St. Joseph Home for the Aged and Crippled, a structure that would also serve as the motherhouse for the order. When it opened in 1898, it became the city's first and oldest Catholic nursing home. One of the industries the nuns took upon themselves to support these charitable activities was a church vestment workshop which opened in 1909 on the second floor. Many of these Polish nuns were expert seamstresses, having learned these skills in the Old World. In 1928 the Franciscan Sisters further expanded the complex by building a new St. Joseph Home of Chicago, a structure that stood until recently at 2650 North Ridgeway. Designed by the distinguished firm of Slupkowski and Piontek who built many of the most prestigious commissions in Chicago's Polish community such as the Art Deco headquarters of the Polish National Alliance, the brick structure was an imposing edifice. One of the building's highlights was a lovely chapel with a masterfully crafted altar that was dedicated to the Black Madonna. The entire complex was sold to a developer who subsequently razed the entire complex, while the new "St. Joseph Village" opened in 2005 on the site of the former Madonna High School and now operates at 4021 W. Belmont Avenue. The park later became home to one of the two first Polish language Saturday schools in Chicago. While the school has since moved out of their small quarters at the park fieldhouse, the Tadeusz Kościuszko School of Polish Language continues to educate over 1,000 students to the present day, reminding all of its origins in Kosciuszko Park with its name.

It was the park of Kosciuszko Park however that wove together the disparate subdivisions and people into one community. Dedicated in 1916, Kosciuszko Park owes its name to the Polish patriot Tadeusz Kosciuszko. Best known as the designer and builder of West Point, Kosciuszko fought in the American Revolution and was awarded with U.S. citizenship and the rank of brigadier general as a reward. Kosciuszko was one of the original parks of the Northwest Park District which was established in 1911. One of the ambitious goals of the Northwest Park District that was in keeping with the spirit of the Progressive Movement popular at the time was to provide one park for each of the ten square miles under its jurisdiction. Beginning in 1914, the district began to purchase land for what would eventually become Mozart, Kelyvn, and Kosciuszko Parks, and improvement on these three sites began almost immediately. For Kosciuszko, noted architect Albert A. Schwartz designed a Tudor revival-style fieldhouse, expanded in 1936 to include an assembly hall, just two years after the 22 separate park districts were consolidated into the Chicago Park District. The park complex expanded during the 1980s with the addition of a new natatorium at the corner of Diversey and Avers.

The green space afforded by the park quickly became the backdrop for community gatherings. Residents utilized the grounds at Kosciuszko Park for bonfires, festivals and neighborhood celebrations, and for a time, even an ice skating rink that would be set up every winter. Summertime brought the opportunity for outdoor festivities, peppered with sports and amateur shows featuring softball games, social dancing, a music appreciation hour, and the occasional visit by the city's "mobile zoo".

Today "The Land of Koz" is a diverse neighborhood, and becoming even more so as gentrification advances further northwest. New people are entering Kosciuszko Park and joining earlier residents whose roots trace back to Latin America and Poland. Yet the park that lent the neighborhood its name still serves its residents, where through play, performance, and even the occasional outdoor film screening it functions as the venue where the community can come together.

Logan Square

[edit]Logan Square is a neighborhood located in the north-central portion of the Logan Square community area in Chicago. The neighborhood boundaries of Logan Square were originally held to be Kimball Avenue on the west, California Avenue to the east, Diversey Parkway on the north, and Fullerton Avenue to the south. However, as memory of the village and later neighborhood of Maplewood has receded, the boundaries have grown beyond these streets, with eastern boundary has now shifted to the North Branch of the Chicago River and the northern border past Diversey Avenue.

The area is characterized by the prominent historical boulevards and large bungalow-style homes. At one time, Logan Square boasted a large Norwegian-American population, centered along the historic boulevards. With relatively inexpensive housing and rent available, this neighborhood was a favorite for immigrants and working-class citizens. Logan Square was the site of the Norwegian-American cultural center, Chicago Norske Klub. Many elaborate, stylish, and expensive houses and mansions line historic Logan and Kedzie Boulevards where the club was once situated. Norwegian Lutheran Memorial Church (Norwegian: Den Norske Lutherske Minnekirke), also known as Minnekirken, is also located on Kedzie Boulevard in Logan Square.[20]

Palmer Square

[edit]

The Palmer Square neighborhood of Chicago is a pocket neighborhood located within the Logan Square community, directly west of Bucktown, north of Humboldt Park, and northwest of Wicker Park. Although there is no clear consensus on this neighborhood's exact boundaries, the City of Chicago Neighborhoods Map shows that it is generally bound by Fullerton Avenue (2400 N) to the north, Armitage Avenue (2000 N) to the south, Kedzie Boulevard (3200 W) to the west, and Milwaukee Avenue to the east.[21]

The neighborhood takes it name from the 7.68-acre (31,100 m2) Palmer Square Park (pictured to the left) that sits near the western edge of the neighborhood and is the namesake of John McAuley Palmer (1817–1900), a lawyer and Civil War General who served as the 15th Governor of Illinois, a United States Senator, and at age 79, was a candidate for president in 1896. Palmer was an avowed abolitionist, friend and supporter of Abraham Lincoln, and, as the Military Governor of Kentucky in 1865–1866, aggressively commanded Federal forces to root out the remnants of slavery in that state.[22]

As the bicycle craze swept Chicago beginning in the mid-1880s, the then-called Palmer Place oval became a popular track for bicycle-riding "wheelmen", also known as "scorchers", who competed with pedestrians and horse-drawn carriages. Ignaz Schwinn (1860–1948), founder of the Schwinn Bicycle Company, lived at the corner of W. Palmer St. and N. Humboldt Blvd.[23] The City of Chicago in 2005 received a matching grant from the Illinois Department of Natural Resources to develop a children's play space, walking trails, soft surface jogging trail, open lawn areas, lighting, seating, and landscaping in Palmer Square. After extensive community input and prolonged design and construction periods, the Chicago Park District (CPD) finished construction of the park and opened it to the public in July 2009.

A series of live music performances in Palmer Square Park takes place each Sunday during the summer of 2021.[24]

Palmer Square's location places its residents within walking distance to a growing number of shops, coffee houses, bars, and restaurants, in particular, on the major streets which form the borders of the neighborhood. The heart of Palmer Square is mainly leafy residential streets. Easy access to the highways and the public transportation system also makes it a popular neighborhood for commuters to the Chicago Loop and for students who attend colleges nearby, such as DePaul University. The neighborhood has easy access to four entrances to the Kennedy Expressway (routes I-90/94) and is served by the California and Western stations of the CTA's Blue Line for a quick ride to Chicago's downtown and O'Hare ![]() . The CTA's bus routes

. The CTA's bus routes 94 California, 56 Milwaukee, 73 Armitage, and 74 Fullerton also run through this neighborhood.

Public libraries

[edit]The Chicago Public Library operates one branch located in the Logan Square community area, the Logan Square Branch at 3030 W. Fullerton. Although the branch in Kosciuszko Park was one of the systems most utilized branches, it was closed by the 1950s.

Cultural organizations

[edit]

Logan Square has a number of diverse cultural centers, such as The Comfort Station, an art gallery and event space, and AnySquared Projects, a nonprofit art collective;[25] St. Hedwig's in Chicago, a strong cultural and civic institution for Chicago's Multiethnic Catholic Community; the Hairpin Arts Center is managed by the Logan Square Chamber of Arts, located in nearby Avondale; as well as Chicago's Polish Village. The Lincoln Lodge on Milwaukee Avenue presents live comedy most nights of the week.[26] Next door is the office of In These Times, an independent magazine founded in 1976 which focuses on social justice.[27]

Media organizations making their home in Logan Square include the Community TV Network—a youth media organization—and the Chicago Independent Media Center. The neighborhood is covered by a number of neighborhood news blogs, including LoganSquarist.[28]

A comprehensive redevelopment of the historic Congress Theater, including its 4,900 seat hall, a 30-room hotel, restaurants, and 14 affordable apartments, was approved by the Chicago City Council in March, 2019.[29] On June 28, 2021, David Baum announced that Baum Revision has taken over the project and is planning to redevelop the landmark theater as well as the surrounding apartments and retail space, using the already approved plan (although excluding the associated 72-unit apartment building).[30] On June 9, 2022, the project was approved by the city's Permit Review Committee; further approval by the full City Council is required before construction may begin. The budget is reported to be $70.4 million, including $9 million in historic tax credits and $20 million in Tax Increment Funding.[31]

Government and infrastructure

[edit]The Roberto Clemente Post Office is located in Logan Square.[32]

Logan Square is served by three stops on the CTA's Blue Line: Western, California, and Logan Square. All three stations provide 24/7 service to O'Hare International Airport, downtown, and Forest Park.

Education

[edit]Residents are zoned to Chicago Public Schools.

The Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Chicago runs Our Lady of Grace School in Logan Square,[33] St. John Berchmans School on Logan Boulevard and St. Sylvester School on Palmer Square.

Politics

[edit]The Logan Square community area has supported the Democratic Party in the past two presidential elections. In the 2016 presidential election, Logan Square cast 27,987 votes for Hillary Clinton and cast 2,435 votes for Donald Trump (86.99% to 7.57%).[34] In the 2012 presidential election, Logan Square cast 22,608 votes for Barack Obama and cast 3,362 votes for Mitt Romney (83.88% to 12.47%).[35]

Notable people

[edit]- Jessica Camacho (born 1982), actress (The Flash, Taken, and Watchmen), was a childhood resident of Logan Square[36]

- Morris Childs (1902–1991), double agent for the F.B.I. against the Soviet Union, was a childhood resident of 3264 West Fullerton Avenue[37][38]

- Eve Ewing (born 1986), sociologist, author, poet, and visual artist, was a childhood resident of Logan Square[39]

- John Guzlowski (born 1948), Polish-American author and poet was a childhood resident of Logan Square[40]

- Lori Lightfoot (born 1962), 56th Mayor of Chicago (2019–2023), resides in Logan Square with her wife and daughter[41]

- Adam Lizakowski (born 1956), a Polish poet, translator, and photographer, former resident, he founded the Unpaid Rent group, a collective of Polish language poets who were based out of his former home in Logan Square[42]

- Richard Nickel (1928–1972), photographer and preservationist, was a childhood resident of Logan Square[43]

- Knute Rockne (1888–1931), football coach, was a childhood resident of Logan Square[44] He grew up in the Logan Square area of Chicago, on the northwest side of the city.[45]

- William A. Redmond (1908–1992), 64th Speaker of the Illinois House of Representatives (1975–1981), was a childhood resident of Logan Square[46]

- Mike Royko (1932–1997), author and Pulitzer Prize winning newspaper columnist, was a childhood resident of Logan Square living at 2122 North Milwaukee Avenue[47]

- Ignaz Schwinn (1860–1948), a designer, a founder, and the eventual sole owner of the Schwinn Bicycle Company[23]

- Shel Silverstein (1930–1999), author and poet, was a childhood resident of Logan Square[48]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Community Data Snapshot - Logan Square" (PDF). cmap.illinois.gov. MetroPulse. Retrieved September 1, 2022.

- ^ Logan Square chicago.gov

- ^ Becker, Lynn (August 10, 2007). "Between the Boulevards: An architectural tour". Chicago Reader. Retrieved March 18, 2009.

- ^ Hermann, Andrew (August 9, 1991). "Public statues are lumberman's legacy to city". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on July 25, 2011. Retrieved March 18, 2009.

- ^ "History of Logan Square". Pillars & Porticos. Retrieved June 28, 2023.

- ^ Paral, Rob. "Chicago Community Areas Historical Data". Archived from the original on March 18, 2013. Retrieved August 30, 2012.

- ^ "The Demographic Statistical Atlas of the United States - Statistical Atlas". statisticalatlas.com. Retrieved June 28, 2023.

- ^ "Longtime Latino Stronghold Logan Square is Now Majority White, New Data Show". December 10, 2020.

- ^ bunten, devin michelle; Preis, Benjamin; Aron-Dine, Shifrah (May 26, 2023). "Re-Measuring Gentrification - Urban Studies". Urban Studies. doi:10.1177/00420980231173846. S2CID 258955054..

- ^ "Home | Kimball Avenue Church". kimballavenuechurch.org. Retrieved August 25, 2015.

- ^ "History of Cook County, Illinois" https://www.google.com/search?kgmid=/g/12bmg909s&hl=en-US&kgs=0e887f29543fe17c&q=history+of+cook+county,+illinois:+being+a+general+survey+of+cook+county+history,+including+a+condensed+history+of+chicago+and+special+account+of+districts+outside+the+city+limits+;+from+the+earliest+settlement+to+the+present+time&shndl=0&source=sh/x/kp/osrp&entrypoint=sh/x/kp/osrp

- ^ Jacob Kaplan, D.P.R.R.E.A.; Pacyga, D. (2014). Avondale and Chicago's Polish Village. Arcadia Publishing. p. 13. ISBN 978-1-4671-1118-8.

- ^ "Seven Lost Wonders of Chicago" https://www.chicagotribune.com/chi-0508290065aug29-story.html chicagotribune.com

- ^ "Chicago Cityscape - Map of building projects, properties, and businesses in Bucktown - Chicago neighborhood". www.chicagocityscape.com. Retrieved June 28, 2023.

- ^ "History – Bucktown Community Org".

- ^ "Cogs In The Machine: Inside Horween Leather in Bucktown". The Huffington Post. June 23, 2011. Retrieved August 15, 2013.

- ^ a b "Northwest Chicago Historical Society - Bucktown". Nwchicagohistory.org. Retrieved August 15, 2013.

- ^ Ukrainian Village & East Village Neighborhood Guide: A Tale of Two Villages. Archived October 6, 2014, at the Wayback Machine Martha Bayne, Chicago Reader, May 8, 2008.

- ^ Greene, Nick (March 7, 2014). "How Chicago's Neighborhoods Got Their Names". Mental Floss.

- ^ Chicago Norske Klub (Norwegian-American Immigration Commission 1825–1925)

- ^ City neighborhoods. Old map

- ^ "John M. Palmer was Civil War leader, political legend". May 12, 2012.

- ^ a b "Palmer (John McAuley) Square Park | Chicago Park District". www.chicagoparkdistrict.com. Retrieved June 28, 2023.

- ^ "Front Porch Jazz Shows Helped Logan Square Neighbors Through 2020 Lockdown. Now, They're Weekly Concerts in Palmer Square Park". June 8, 2021.

- ^ "AnySquared Projects". anysquared.com. Retrieved June 28, 2023.

- ^ "Calendar".

- ^ "In These Times". In These Times. Retrieved June 28, 2023.

- ^ "Home". LoganSquarist. Retrieved June 28, 2023.

- ^ "Office of the City Clerk - Record #: SO2019-1050".

- ^ "Long-Vacant Congress Theater Could Reopen in 2023 with New Developer on Board". June 29, 2021.

- ^ "Landmarks approves Congress Theater redevelopment". June 14, 2022.

- ^ "Post Office™ Location – ROBERTO CLEMENTE Archived July 10, 2010, at the Wayback Machine". United States Postal Service. Retrieved on January 23, 2011.

- ^ "About OLG Archived January 25, 2011, at the Wayback Machine". Our Lady of Grace School. Retrieved on April 14, 2011.

- ^ Ali, Tanveer (November 9, 2016). "How Every Chicago Neighborhood Voted In The 2016 Presidential Election". DNAInfo. Archived from the original on September 24, 2019. Retrieved October 4, 2019.

- ^ Ali, Tanveer (November 9, 2012). "How Every Chicago Neighborhood Voted In The 2012 Presidential Election". DNAInfo. Archived from the original on February 3, 2019. Retrieved October 4, 2019.

- ^ Delany, Beth (December 19, 2019). "Living the Dream". Splash. Retrieved October 15, 2019.

- ^ United States Census Records Found via Heritage Quest Online. Use last name Chilovsky to find.

- ^ West, Nigel (May 21, 2015). Historical Dictionary of International Intelligence. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 64. ISBN 9781442249578. Retrieved November 29, 2021.

- ^ Morgan, Adam (August 17, 2017). "The Next Generation of Chicago Afrofuturism". Chicago Magazine. Retrieved September 5, 2017.

- ^ Dixon, Lauren (June 20, 2017). "Refugees of Logan Square". LoganSquarist. Retrieved July 12, 2020.

- ^ "Lori Lightfoot On Why She Chose To Live In Logan Square And How Living There Shaped Her Worldview". Block Club Chicago. Retrieved June 1, 2019.

- ^ Bauer, Mark (May 15, 2003). "Magnetic Pole". Chicago Reader. Retrieved July 12, 2020.

- ^ Cahan, Richard (1994). They All Fall Down: Richard Nickel's Struggle to Save America's Architecture. Wiley. p. 32. ISBN 978-0471144267.

- ^ "Death of Rockne". Time Magazine. April 6, 1931. Archived from the original on December 15, 2008. Retrieved January 23, 2009.

- ^ Cutler, Irving (2006). Chicago, Metropolis of the Mid-continent. SIU Press. p. 75. ISBN 9780809387953.

- ^ "William A. Redmond Memoir". Illinois Legislative Research Unit. 1982. Retrieved July 11, 2016.

- ^ "Mike Royko Street Honor the Right Idea, Group Says". DNAinfo Chicago. Archived from the original on August 29, 2019. Retrieved August 29, 2019.

- ^ Alessio, Carolyn (May 11, 1999). "A Poet with Heart and Edge". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved December 21, 2018.

External links

[edit]- Official City of Chicago Logan Square Community Map

- Bucktown Community Organization

- The Northwest Chicago Historical Society's history of Bucktown

- Logan Square Preservation

- Logan Square Chamber of Commerce

- Logan Square Neighborhood Association

- Wicker Park & Bucktown Chamber of Commerce

- Palmer Square

- Chicago Norske Klub