New religious movement

A new religious movement (NRM), also known as alternative spirituality or a new religion, is a religious or spiritual group that has modern origins and is peripheral to its society's dominant religious culture. NRMs can be novel in origin, or they can be part of a wider religion, in which case they are distinct from pre-existing denominations. Some NRMs deal with the challenges that the modernizing world poses to them by embracing individualism, while other NRMs deal with them by embracing tightly knit collective means.[1] Scholars have estimated that NRMs number in the tens of thousands worldwide. Most NRMs only have a few members, some of them have thousands of members, and a few of them have more than a million members.[2]

There is no single, agreed-upon criterion for defining a "new religious movement".[3] Debate continues as to how the term "new" should be interpreted in this context.[4] One perspective is that it should designate a religion that is more recent in its origins than large, well-established religions like Hinduism, Judaism, Buddhism, Christianity, and Islam.[4] Some scholars view the 1950s or the end of the Second World War in 1945 as the defining time,[5] while others look as far back as the founding of the Latter Day Saint movement in 1830[4][6] and of Tenrikyo in 1838.[7][8]

New religions have sometimes faced opposition from established religious organisations and secular institutions. In Western nations, a secular anti-cult movement and a Christian countercult movement emerged during the 1970s and 1980s to oppose emergent groups. A distinct field of new religion studies developed within the academic study of religion in the 1970s. There are several scholarly organisations and peer-reviewed journals devoted to the subject. Religious studies scholars contextualize the rise of NRMs in modernity as a product of, and answer to, modern processes of secularization, globalization, detraditionalization, fragmentation, reflexivity, and individualization.[1]

History

[edit]

In 1830, the Latter Day Saint movement was founded by Joseph Smith. It is one of the largest new religious movements in terms of membership.[9] In Japan, 1838 marks the beginning of Tenrikyo.[7] In 1844, Bábism was established in Iran, from which the Baháʼí Faith was founded by Bahá'u'lláh in 1863. In 1860, Donghak, later Cheondoism, was founded by Choi Jae-Woo in Korea. It later ignited the Donghak Peasant Revolution in 1894.[10] In 1889, Ahmadiyya, an Islamic branch, was founded by Mirza Ghulam Ahmad. In 1891, the Unity Church, the first New Thought denomination, was founded in the United States.[6][11]

In 1893, the first Parliament of the World's Religions was held in Chicago.[12] The conference included NRMs of the time such as spiritualism, Baháʼí Faith, and Christian Science. Henry Harris Jessup, who addressed the meeting, was the first to mention the Baháʼí Faith in the United States.[13] Also attending were Soyen Shaku, the "First American Ancestor" of Zen,[14] the Theravāda Buddhist preacher Anagarika Dharmapala, and the Jain preacher Virchand Gandhi.[15] This conference gave Asian religious teachers their first wide American audience.[6]

In 1911, the Nazareth Baptist Church, the first and one of the largest modern African initiated churches, was founded by Isaiah Shembe in South Africa.[6][16] The early 20th century also saw a rise in interest in Asatru. The 1930s saw the rise of the Nation of Islam and the Jehovah's Witnesses in the United States; the rise of the Rastafari movement in Jamaica; the rise of Cao Đài and Hòa Hảo in Vietnam; the rise of Soka Gakkai in Japan; and the rise Zailiism and Yiguandao in China. In the 1940s, Gerald Gardner began to outline the modern pagan religion of Wicca.

New religious movements expanded in many nations in the 1950s and 1960s at the height of the counterculture movements. Japanese new religions became very popular after the Shinto Directive (1945) forced the Japanese government to separate itself from Shinto, which had been the state religion of Japan, bringing about greater freedom of religion.

In 1954, Scientology was founded in the United States, and the Unification Church was founded in South Korea.[6] In 1955, the Aetherius Society was founded in England. It and some other NRMs have been called UFO religions because they combine the belief in extraterrestrial life with traditional religious principles.[17][18][19]

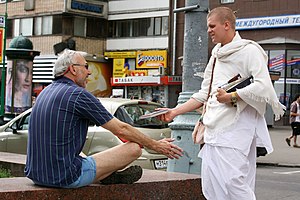

In 1965, Paul Twitchell founded Eckankar, an NRM derived partially from Sant Mat. In 1966, the International Society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON) was founded in the United States by A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada,[20] and Anton LaVey founded the atheist Church of Satan. In 1967, the Beatles visit to Maharishi Mahesh Yogi in India brought public attention to the Transcendental Meditation movement.[21][22]

In the late 1980s and 1990s, the decline of communism and the revolutions of 1989 opened up new opportunities for NRMs. Falun Gong was first taught publicly in Northeast China in 1992 by Li Hongzhi. At first, it was accepted by the Chinese government, and by 1999 there were 70 million practitioners in China.[23][24] But in July 1999, the government started to view the movement as a threat and began attempts to eradicate it.

In the 21st century, many NRMs are using the Internet to give out information, recruit members, and sometimes to hold online meetings and rituals.[6] That is sometimes referred to as cybersectarianism.[25][26] Sabina Magliocco, professor of Anthropology and Folklore at California State University, Northridge, has discussed the growing popularity of new religious movements on the Internet.[27]

In 2006 J. Gordon Melton, executive director of the Institute for the Study of American Religions at the University of California, Santa Barbara, told The New York Times that 40 to 45 new religious movements emerge each year in the United States.[28]

In 2007, religious scholar Elijah Siegler said that, though no NRM had become the dominant faith in any country, many of the concepts they first introduced (often referred to as "New Age" ideas) have become part of worldwide mainstream culture.[6]

Beliefs and practices

[edit]

Eileen Barker has argued that NRMs should not be "lumped together," as they differ from one another on many issues.[29] Virtually no generalisation can be made about NRMs that applies to every group,[30] with David V. Barrett noting that "generalizations tend not to be very helpful" when studying NRMs.[31] J. Gordon Melton expressed the view that there is "no single characteristic or set of characteristics" that all new religions share, "not even their newness."[32] Bryan Wilson wrote, "Chief among the miss-directed assertions has been the tendency to speak of new religious movements as if they differed very little, if at all, one from another. The tendency has been to lump them together and indiscriminately attribute all of the characteristics which are, in fact, valid for only one or two."[33] NRMs themselves often claim that they exist at a crucial place in time and space.[34]

Scriptures

[edit]Some NRMs venerate unique scriptures, while others reinterpret existing texts,[35] utilizing a range of older elements.[36] They frequently claim that these are not new but rather forgotten truths that are being revived.[37] NRM scriptures often incorporate modern scientific knowledge, sometimes with the claim that they are bringing unity to science and religion.[38] Some NRMs believe that their scriptures are received through mediums.[39] The Urantia Book, the core scripture of the Urantia Movement, was published in 1955 and is said to be the product of a continuous process of revelation from "celestial beings" which began in 1911.[40] Some NRMs, particularly those that are forms of occultism, have a prescribed system of courses and grades through which members can progress.[41]

Celibacy

[edit]Some NRMs promote celibacy, the state of voluntarily being unmarried, sexually abstinent, or both. Some, including the Shakers and more recent NRMs, inspired by Hindu traditions, see it as a lifelong commitment. Others, including the Unification Church, as a stage in spiritual development.[42] In some Buddhist NRMs, celibacy is practiced mostly by older women who become nuns.[43] Some people join NRMs and practice celibacy as a rite of passage in order to move beyond previous sexual problems or bad experiences.[44] Groups that promote celibacy require a strong recruitment drive to survive. The Shakers established orphanages, hoping that the children would become members of their community.[45]

Violence

[edit]Violent incidents involving NRMs are very rare. In events having a large number of casualties, the new religion was led by a charismatic leader.[46] Beginning in 1978, the deaths of 913 members of the Peoples Temple in Jonestown, Guyana, by both murder and suicide brought an image of "killer cults" to public attention. Several subsequent events contributed to the concept. In 1994, members of the Order of the Solar Temple committed suicide in Canada and Switzerland. In 1997, 39 members of the Heaven's Gate group committed suicide in the belief that their spirits would leave the Earth and join a passing comet.[47] There have also been cases in which members of NRMs have been killed after they engaged in dangerous actions due to mistaken belief in their own invincibility. For example, in Uganda, several hundred members of the Holy Spirit Movement were killed as they approached gunfire because its leader, Alice Lakwena, told them that they would be protected from bullets by the oil of the shea tree.[48] The history of the Latter Day Saint movement includes multiple cases of significant violence committed by or against Mormons.

Leadership and succession

[edit]

NRMs are typically founded and led by a charismatic leader.[49] The death of any religion's founder represents a significant moment in its history. Over the months and years following its leader's death, the movement can die out, fragment into multiple groups, consolidate its position, or change its nature to become something quite different from what its founder intended. In some cases, a NRM moves closer to the religious mainstream after the death of its founder.[50]

A number of founders of new religions established plans for succession to prevent confusion after their deaths. Mary Baker Eddy, the American founder of Christian Science, spent fifteen years working on her book The Manual of the Mother Church, which laid out how the group should be run by her successors.[51] The leadership of the Baháʼí Faith passed through a succession of individuals until 1963, when it was assumed by the Universal House of Justice, members of which are elected by the worldwide congregation.[52][53] A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, the founder of the International Society for Krishna Consciousness, appointed 11 "Western Gurus" to act as initiating gurus and to continue to direct the organisation.[54][55][56] However, according to British scholar of religion Gavin Flood, "many problems followed from their appointment and the movement has since veered away from investing absolute authority in a few, fallible, human teachers."[57]

Membership

[edit]Demographics

[edit]NRMs typically consist largely of first-generation believers,[58] and thus often have a younger average membership than mainstream religious congregations.[59] Some NRMs have been formed by groups who have split from a pre-existing religious group.[49] As these members grow older, many have children who are then brought up within the NRM.[60]

In the Third World, NRMs most often appeal to the poor and oppressed sectors of society.[61] Within Western countries, they are more likely to appeal to members of the middle and upper-middle classes,[61] with Barrett stating that new religions in the UK and US largely attract "white, middle-class late teens and twenties".[62] There are exceptions, such as the Rastafari movement and the Nation of Islam, which have primarily attracted Black members.[61]

A popular conception, unsupported by evidence, holds that those who convert to new religions are either mentally ill or become so through their involvement with them.[63] Dick Anthony, a forensic psychologist noted for his writings on the brainwashing controversy,[64][65] has defended NRMs, and in 1988 argued that involvement in such movements may often be beneficial: "There's a large research literature published in mainstream journals on the mental health effects of new religions. For the most part, the effects seem to be positive in any way that's measurable."[66]

Joining

[edit]Those who convert to a NRM typically believe that in doing so they are gaining some benefit in their life. This can come in many forms, from an increasing sense of freedom to a release from drug dependency, and a feeling of self-respect and direction. Many of those who have left NRMs report that they have gained from their experience. There are various reasons as to why an individual would join and then remain part of a NRM, including both push and pull factors.[67] According to Marc Galanter, professor of psychiatry at NYU,[68] typical reasons why people join NRMs include a search for community and a spiritual quest. Sociologists Stark and Bainbridge, in discussing the process by which people join new religious groups, have questioned the utility of the concept of conversion, suggesting that affiliation is a more useful concept.[69]

A popular explanation for why people join new religious movements is that they have been "brainwashed" or subject to "mind control" by the NRM itself.[70] This explanation provides a rationale for "deprogramming", a process in which members of NRMs are illegally kidnapped by individuals who then attempt to convince them to reject their beliefs.[70] Professional deprogrammers, therefore, have a financial interest in promoting the "brainwashing" explanation.[71] Academic research, however, has demonstrated that these brainwashing techniques "simply do not exist".[72]

Leaving

[edit]Many members of NRMs leave these groups of their own free will.[73] Some of those who do so retain friends within the movement.[74] Some of those who leave a religious community are unhappy with the time that they spent as part of it.[74] Leaving a NRM can pose a number of difficulties.[75] It may result in their having to abandon a daily framework that they had previously adhered to.[76] It may also generate mixed emotions as ex-members lose the feelings of absolute certainty, which they may have held while in the group.[75]

Reception

[edit]Academic scholarship

[edit]Three basic questions have been paramount in orienting theory and research on NRMs: what are the identifying markers of NRMs that distinguish them from other types of religious groups?; what are the different types of NRMs and how do these different types relate to the established institutional order of the host society?; and what are the most important ways that NRMs respond to the sociocultural dislocation that leads to their formation?

— Sociologist of religion David G. Bromley[77]

The academic study of new religious movements is known as 'new religions studies' (NRS).[78] The study draws from the disciplines of anthropology, psychiatry, history, psychology, sociology, religious studies, and theology.[79] Barker noted that there are five sources of information on NRMs: the information provided by such groups themselves, that provided by ex-members as well as the friends and relatives of members, organisations that collect information on NRMs, the mainstream media, and academics studying such phenomena.[80]

The study of new religions is unified by its topic of interest rather than by its methodology, and is therefore interdisciplinary in nature.[81] A sizeable body of scholarly literature on new religions has been published, most of it produced by social scientists.[82] Among the disciplines that NRS utilises are anthropology, history, psychology, religious studies, and sociology.[83] Of these approaches, sociology played a particularly prominent role in the development of the field,[83] resulting in it being initially confined largely to a narrow array of sociological questions.[84] This came to change in later scholarship, which began to apply theories and methods initially developed for examining more mainstream religions to the study of new ones.[84]

Most research has been directed toward those new religions that attract public controversy. Less controversial NRMs tend to be the subject of less scholarly research.[85] It has also been noted that scholars of new religions often avoid researching certain movements that scholars from other backgrounds study. The feminist spirituality movement is usually examined by scholars of women's studies, African-American new religions by scholars of Africana studies, and Native American new religions by scholars of Native American studies.[86]

Definitions and terminology

[edit]

J. Gordon Melton argued that "new religious movements" should be defined by the way dominant religious and secular forces within a given society treat them. According to him, NRMs constituted "those religious groups that have been found, from the perspective of the dominant religious community (and in the West that is almost always a form of Christianity), to be not just different, but unacceptably different."[87] Barker cautioned against Melton's approach, arguing that negating the "newness" of "new religious movements" raises problems, for it is "the very fact that NRMs are new that explains many of the key characteristics they display".[88]

George Chryssides favors "simple" definition; for him, NRM is an organization founded within the past 150 or so years, which cannot be easily classified within one of the world's main religious traditions.[89]

Scholars of religion Olav Hammer and Mikael Rothstein argued that "new religions are just young religions" and as a result, they are "not inherently different" from mainstream and established religious movements, with the differences between the two having been greatly exaggerated by the media and popular perceptions.[72] Melton has stated that those NRMs that "were offshoots of older religious groups... tended to resemble their parent groups far more than they resembled each other."[32]

One question that faces scholars of religion is when a new religious movement ceases to be "new".[90] As noted by Barker, "In the first century, Christianity was new, in the seventh century Islam was new, in the eighteenth century Methodism was new, in the nineteenth century the Seventh-day Adventists, Christadelphians, and Jehovah's Witnesses were new; in the twenty-first century the Unification Church, the ISKCON, and Scientology are beginning to look old."[90]

The Roman Catholic Church has observed that the growth of sects and new religious movements is one of the "most noticeable" and "highly complex" developments in recent years, and in relation to the ecumenical movement, their "desire for peaceful relations with the Catholic Church may be weak or non-existent".[91]

Some NRMs are strongly counter-cultural and 'alternative' in the society where they appear, while others are far more similar to a society's established traditional religions.[92] Generally, Christian denominations are not seen as new religious movements; nevertheless, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, the Jehovah's Witnesses, Christian Science, and the Shakers have been studied as NRMs.[93][94] The same situation with Jewish religious movements, when Reform Judaism and newer divisions have been named among NRM.[95]

There are also problems in the use of "religion" within the term "new religious movements".[96] This is because various groups, particularly active within the New Age milieu, have many traits in common with different NRMs but emphasise personal development and humanistic psychology, and are not clearly "religious" in nature.[97]

Since at least the early 2000s, most sociologists of religion have used the term "new religious movement" in order to avoid the pejorative undertones of terms like "cult" and "sect".[98] These are words that have been used in different ways by different groups.[99] For instance, from the nineteenth century onward a number of sociologists used the terms "cult" and "sect" in very specific ways.[100] The sociologist Ernst Troeltsch for instance differentiated "churches" from "sect" by claiming that the former term should apply to groups that stretch across social strata while "sects" typically contain converts from socially disadvantaged sectors of society.[100]

The term "cult" is used in reference to devotion or dedication to a particular person or place.[101] For instance, within the Roman Catholic Church, devotion to Mary, mother of Jesus may be termed the "Cult of Mary".[102] It is also used in non-religious contexts to refer to fandoms devoted to television shows like The Prisoner, The X-Files, and Buffy the Vampire Slayer.[103] In the United States, people began to use "cult" in a pejorative manner, to refer to Spiritualism and Christian Science during the 1890s.[104] As commonly used, for instance in sensationalist tabloid articles, the term "cult" continues to have pejorative associations.[105]

The term "new religions" is a calque of shinshūkyō (新宗教), a Japanese term developed to describe the proliferation of Japanese new religions in the years following the Second World War.[106] From Japan this term was translated and used by several American authors, including Jacob Needleman, to describe the range of groups that appeared in the San Francisco Bay Area during the 1960s.[107] This term, amongst others, was adopted by Western scholars as an alternative to "cult".[108] However, "new religious movements" has failed to gain widespread public usage in the manner that "cult" has.[109] Other terms that have been employed for many NRMs are "alternative religion" and "alternative spirituality", something used to convey the difference between these groups and established or mainstream religious movements while at the same time evading the problem posed by groups that are not particularly new.[110]

The 1970s was the era of the so-called "cult wars", led by "cult-watching groups".[111] The efforts of the anti-cult movement condensed a moral panic around the concept of cults. Public fears around Satanism, in particular, came to be known as a distinct phenomenon, the "Satanic Panic".[112] Consequently, scholars such as Eileen Barker, James T. Richardson, Timothy Miller and Catherine Wessinger argued that the term "cult" had become too laden with negative connotations, and "advocated dropping its use in academia". A number of alternatives to the term "new religious movement" are used by some scholars. These include "alternative religious movements" (Miller), "emergent religions" (Ellwood) and "marginal religious movements" (Harper and Le Beau).[94]

Opposition

[edit]The 1960s and 1970s saw the emergence of a number of highly visible new religious movements... [These] seemed so outlandish that many people saw them as evil cults, fraudulent organizations or scams that recruited unaware people by means of mind-control techniques. Real or serious religions, it was felt, should appear in recognizable institutionalized forms, be suitably ancient, and – above all – advocate relatively familiar theological notions and modes of conduct. Most new religions failed to comply with such standards.

— Religious studies scholars Olav Hammer and Mikael Rothstein[113]

There has been opposition to NRMs throughout their history.[114] Some historical events have been: Anti-Mormonism,[115] the persecution of Jehovah's Witnesses,[116] the persecution of Baháʼís,[117] and the persecution of Falun Gong.[118] There are also instances in which violence has been directed at new religions.[119] In the United States the founder of the Latter Day Saint movement, Joseph Smith, was killed by a lynch mob in 1844.[120] In India there have been mob killings of members of the Ananda Marga group.[119] Such violence can also be administered by the state.[119] In Iran, followers of the Baháʼí Faith have faced persecution, while the Ahmadiyya have faced similar violence in Pakistan.[121] Since 1999, the persecution of Falun Gong in China has been severe.[118][122] Ethan Gutmann interviewed over 100 witnesses and estimated that 65,000 Falun Gong practitioners were killed for their organs from 2000 to 2008.[123][124][125][126]

Christian countercult movement

[edit]In the 1930s, Christian critics of NRMs began referring to them as "cults". The 1938 book The Chaos of Cults by Jan Karel van Baalen (1890–1968), an ordained minister in the Christian Reformed Church in North America, was especially influential.[6][127] In the US, the Christian Research Institute was founded in 1960 by Walter Ralston Martin to counter opposition to evangelical Christianity and has come to focus on criticisms of NRMs.[128] Presently the Christian countercult movement opposes most NRMs because of theological differences. It is closely associated with evangelical Christianity.[129]

In his book The Kingdom of the Cults (1965), Christian scholar Walter Ralston Martin[130]: 18 [131] examines a large number of new religious movements; included are major groups such as Christian Science, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Jehovah's Witnesses, Armstrongism, Theosophy, the Baháʼí Faith, Unitarian Universalism, Scientology, the Unity Church, as well as minor groups including various New Age groups and those based on Eastern religions. The beliefs of other world religions such as Islam and Buddhism are also discussed. He covers each group's history and teachings, and contrasts them with those of mainstream Christianity.[131][132]

Anti-cult movement

[edit]In the 1970s and 1980s, some NRMs as well as some non-religious groups came under opposition by the newly organized anti-cult movement, which mainly charged them with psychological abuse of their own members.[6] It actively seeks to discourage people from joining new religions (which it refers to as "cults"). It also encourages members of these groups to leave them, and at times seeking to restrict their freedom of movement.[129]

Family members are often distressed when a relative of theirs joins a new religion.[133] Although children break away from their parents for all manner of reasons, in cases where NRMs are involved, it is often the latter that are blamed for the break.[134] Some anti-cultist groups emphasise the idea that "cults" use deceit and trickery to recruit members.[135] The anti-cult movement adopted the term brainwashing, which had been developed by the journalist Edward Hunter and then used by Robert J. Lifton to apply to the methods employed by Chinese to convert captured US soldiers to their cause in the Korean War. Lifton himself had doubts about the applicability of his brainwashing hypothesis to the techniques used by NRMs to convert recruits.[136]

A number of ex-members of various new religions have made false allegations about their experiences in such groups. For instance, in the late 1980s a man in Dublin, Ireland, was given a three-year suspended sentence for falsely claiming that he had been drugged, kidnapped, and held captive by members of ISKCON.[137]

Scholars of religion have often critiqued anti-cult groups of un-critically believing anecdotal stories provided by the ex-members of new religions, of encouraging ex-members to think that they are the victims of manipulation and abuse, and of irresponsibly scare-mongering about NRMs.[138] Of the "well over a thousand groups that have been or might be called cults" listed in the files of INFORM, writes Eileen Barker, the "vast majority" have not engaged in criminal activities.[139]

Popular culture and news media

[edit]New religious movements and cults have appeared as themes or subjects in literature and popular culture, while notable representatives of such groups have produced a large body of literary works. Beginning in the 1700s authors in the English-speaking world began introducing members of "cults" as antagonists. In the twentieth century, concern for the rights and feelings of religious minorities led authors to most often invent fictional cults for their villains to be members of.[140] Fictional cults continue to be popular in film, television, and gaming in the same way, while some popular works treat new religious movements in a serious manner.

An article on the categorization of new religious movements in US print media published by The Association for the Sociology of Religion (formerly the American Catholic Sociological Society), criticizes the print media for failing to recognize social-scientific efforts in the area of new religious movements, and its tendency to use popular or anti-cultist definitions rather than social-scientific insight, and asserts that "The failure of the print media to recognize social-scientific efforts in the area of religious movement organizations impels us to add yet another failing mark to the media report card Weiss (1985) has constructed to assess the media's reporting of the social sciences."[141]

See also

[edit]- List of new religious movements

- New religious movements and cults in popular culture

- Cult

- History of religion

- Religious pluralism

- Religious trauma syndrome

- Sociological classifications of religious movements

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b Clarke 2006a.

- ^ Eileen Barker, 1999, "New Religious Movements: their incidence and significance", New Religious Movements: challenge and response, Bryan Wilson and Jamie Cresswell editors, Routledge ISBN 0-415-20050-4

- ^ Oliver 2012, pp. 5–6.

- ^ a b c Oliver 2012, p. 14.

- ^ Barker 1989, pp. 6, 143.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Elijah Siegler, 2007, New Religious Movements, Prentice Hall, ISBN 0-13-183478-9

- ^ a b Clarke 2006b, pp. 621–623, Tenrikyo.

- ^ A notable proponent of the earlier dating is George Chryssides (Driedger & Wolfart 2018, pp. 5–12).

- ^ Harvey, Sarah (2020-09-24). "Factsheet: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints". Religion Media Centre. Retrieved 2024-02-22.

- ^ Yao, Xinzhong (2000). An Introduction to Confucianism. Cambridge University Press. pp. 121–122. ISBN 978-0-521-64430-3.

- ^ "Unity School of Christianity". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 2009-12-20. Retrieved 2009-06-26.

- ^ McRae, John R. (1991). "Oriental Verities on the American Frontier: The 1893 World's Parliament of Religions and the Thought of Masao Abe". Buddhist-Christian Studies. 11: 7–36. doi:10.2307/1390252. JSTOR 1390252.

- ^ "First Public Mentions of the Baháʼí Faith in the West". bahai-library.com. Archived from the original on 2012-07-16. Retrieved 2013-02-24.

- ^ Ford, James Ishmael (2006). Zen Master Who?. Wisdom Publications. pp. 59–62. ISBN 978-0-86171-509-1.

- ^ Jain, Pankaz; Pankaz Hingarh; Bipin Doshi and Smt. Priti Shah. "Virchand Gandhi, A Gandhi Before Gandhi". herenow4u. Archived from the original on 2015-09-29. Retrieved 2013-02-24.

- ^ Fisher, Jonah (16 January 2010). "Unholy row over World Cup trumpet". BBC Sport. Archived from the original on 2012-07-11. Retrieved 2010-01-16.

- ^ Partridge, Christopher Hugh (ed.) (2003) UFO Religions. Routledge. Chapter 4 Opening A Channel To The Stars: The Origins and Development of the Aetherius Society by Simon G. Smith pp. 84–102

- ^ James R. Lewis (ed.) (1995), The Gods have landed: new religions from other worlds (Albany: State University of New York Press),ISBN 0-7914-2330-1. p. 28

- ^ Sablia, John A. (2006). The Study of UFO Religions, Nova Religio: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions, November 2006, Vol. 10, No. 2, pp. 103–123.

- ^ Gibson 2002, pp. 4, 6

- ^ van den Berg, Stephanie (5 February 2008). "Beatles Guru Maharishi Mahesh Yogi Dies". The Sydney Morning Herald. AFP. Archived from the original on 29 August 2010.

- ^ Corder, Mike (10 February 2008). "Maharishi Mahesh Yogi; The Beatles' mentor had global empire". San Diego Union-Tribune. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 17 July 2011.

- ^ Seth Faison (27 April 1999) In Beijing: A Roar of Silent Protestors Archived 2018-03-20 at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times

- ^ "In July 1999, the CCP Created Exactly What It Had Feared". thediplomat.com. Archived from the original on 2020-08-04. Retrieved 2020-06-06.

- ^ Paul Virilio,The Information Bomb (Verso, 2005), p. 41.

- ^ Rita M. Hauck, "Stratospheric Transparency: Perspectives on Internet Privacy, Forum on Public Policy (Summer 2009) "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-04-20. Retrieved 2013-02-25.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Magliocco, Sabina. 2012. “Neopaganism.” In O. Hammer and M. Rothstein, Eds., The Cambridge Companion to New Religious Movements, pp. 150–166. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Seeking Entry-Level Prophet: Burning Bush and Tablets Not Required Archived 2016-12-04 at the Wayback Machine, New York Times, August 28, 2006

- ^ Barker 1989, p. 1.

- ^ Barker 1989, p. 10.

- ^ Barrett 2001, p. 9.

- ^ a b Melton 2004, p. 76.

- ^ Bryan Wilson. "Why the Bruderhof is not a cult". Cult And Sect | Religion And Belief. Scribd. Archived from the original on 2021-03-08. Retrieved 2017-07-07.

- ^ Hammer & Rothstein 2012, p. 6.

- ^ John Bowker, 2011, The Message and the Book, UK, Atlantic Books, pp. 13–14

- ^ Hammer & Rothstein 2012, p. 7.

- ^ Hammer & Rothstein 2012, p. 8.

- ^ Zeller, Benjamin (2010). Prophets and Protons: New Religious Movements and Science in Late Twentieth-Century America. New York University Press. pp. 10–15. ISBN 978-0-8147-9721-1.

- ^ The Bloomsbury Companion to New Religious Movements, George D. Chryssides, Benjamin E. Zeller, A&C Black, 2014, p. 214

- ^ Gardner 1995, p. 11.

- ^ Barrett 2001, p. 57.

- ^ Teaching New Religious Movements, David G. Bromley, Oxford University Press, May 25, 2007

- ^ New Religious Movements: Challenge and Response, Jamie Cresswell, Bryan Wilson, Routledge, 2012, p. 153

- ^ The Oxford Handbook of New Religious Movements, Volume 1, James R Lewis, OUP US, 2008, p. 385

- ^ Barrett 2001, p. 67.

- ^ Barrett 2001, p. 83.

- ^ Barrett 2001, p. 82.

- ^ Barker 1989, p. 55.

- ^ a b Barker 1989, p. 13.

- ^ Barrett 2001, pp. 58–60.

- ^ Barrett 2001, p. 66.

- ^ Baha'i World Statistics 2001 Archived 2007-10-17 at the Wayback Machine by Baha'i World Center Department of Statistics, 2001–08

- ^ The Life of Shoghi Effendi Archived 2010-09-19 at the Wayback Machine by Helen Danesh, John Danesh and Amelia Danesh, Studying the Writings of Shoghi Effendi, edited by M. Bergsmo (Oxford: George Ronald, 1991)

- ^ Ron Rhodes (2001). Challenge of the Cults and New Religions. Zondervan. p. 179. ISBN 978-0-310-23217-9.

Before Prabhupada died in 1977, he selected senior devotees who would continue to direct the organization.

- ^ Smith, Huston; Harry Oldmeadow (2004). Journeys East: 20th century Western encounters with Eastern religious traditions. Bloomington, IN: World Wisdom. p. 272. ISBN 978-0-941532-57-0.

Before his death Prabhupada appointed eleven American devotees as gurus.

- ^ Rochford, E. Burke (1985). Hare Krishna in America. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. p. 222. ISBN 978-0-8135-1114-6.

In the months preceding his death Srila Prabhupada appointed eleven of his closest disciples to act as initiating gurus for ISKCON

- ^ Flood, G.D. (1996). An Introduction to Hinduism. Cambridge University Press. p. 272. ISBN 978-0-521-43878-0.

Upon demise of Prabhupada eleven Western Gurus were selected as spiritual heads of the Hare Krsna movement, but many problems followed from their appointment and the movement had since veered away from investing absolute authority in a few, fallible, human teachers.

- ^ Barker 1989, p. 11.

- ^ Barker 1989, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Barker 1989, p. 12.

- ^ a b c Barker 1989, p. 14.

- ^ Barrett 2001, p. 98.

- ^ Barker 1989, pp. 55–56.

- ^ Dawson, Lorne L. Cults in context: readings in the study of new religious movements, Transaction Publishers 1998, p. 340, ISBN 978-0-7658-0478-5

- ^ Robbins, Thomas. In Gods we trust: new patterns of religious pluralism in America, Transaction Publishers 1996, p. 537, ISBN 978-0-88738-800-2

- ^ Sipchen, Bob (1988-11-17). "Ten Years After Jonestown, the Battle Intensifies Over the Influence of 'Alternative' Religions" , Los Angeles Times

- ^ Barker 1989, pp. 25–26.

- ^ Galanter, Marc (Editor), (1989), Cults and new religious movements: a report of the committee on psychiatry and religion of the American Psychiatric Association, ISBN 0-89042-212-5

- ^ Bader, Chris & A. Demarish (1996). "A test of the Stark-Bainbridge theory of affiliation with religious cults and sects." Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 35, 285–303.

- ^ a b Barker 1989, p. 17.

- ^ Barker 1989, p. 19.

- ^ a b Hammer & Rothstein 2012, p. 3.

- ^ Barker 1989, pp. 18–19.

- ^ a b Barrett 2001, p. 47.

- ^ a b Barrett 2001, p. 54.

- ^ Barrett 2001, p. 55.

- ^ Bromley 2012, p. 14.

- ^ Bromley 2004, p. 83; Bromley 2012, p. 13.

- ^ Sablia, John A. (2007). "Disciplinary Perspectives on New Religious Movements: Views of from the Humanities and Social Sciences". In David G. Brohmley (ed.). Teaching New Religious Movements. Oxford University Press. pp. 41–63. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195177299.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-978553-7. Archived from the original on 2021-11-07. Retrieved 2014-03-17.

- ^ Barker 1989, pp. vii–ix.

- ^ Lewis 2004, p. 8; Melton 2004b, p. 16.

- ^ Bromley 2012, p. 13; Hammer & Rothstein 2012, p. 2.

- ^ a b Bromley 2012, p. 13.

- ^ a b Hammer & Rothstein 2012, p. 5.

- ^ Melton 2004b, p. 20.

- ^ Lewis 2004, p. 8.

- ^ Melton 2004, p. 79.

- ^ Barker 2004, p. 89.

- ^ Driedger & Wolfart 2018, pp. 5–12.

- ^ a b Barker 2004, p. 99.

- ^ Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity (1993-03-25). Directory for the Application of Principles and Norms on Ecumenism (PDF). p. 12. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-12-18. Retrieved 16 November 2022 – via Office of Divine Worship, Diocese of Philadelphia.

- ^ Oliver 2012, p. 5.

- ^ Rubinstein 2023.

- ^ a b Olson, Paul J. (2006). "The Public Perception of 'Cults' and 'New Religious Movements'". Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 45 (1): 97–106. doi:10.1111/j.1468-5906.2006.00008.x.

- ^ Clarke 2006b, pp. 525–526, Reform Judaism.

- ^ Oliver 2012, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Oliver 2012, p. 15.

- ^ Barrett 2001, p. 24.

- ^ Barrett 2001, p. 19.

- ^ a b Barrett 2001, p. 23.

- ^ Barrett 2001, p. 21.

- ^ Barrett 2001, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Barrett 2001, p. 22.

- ^ Melton 2004b, p. 17.

- ^ Barrett 2001, p. 20.

- ^ Lewis 2004, p. 3; Melton 2004b, p. 19.

- ^ Melton 2004b, p. 19.

- ^ Gallagher, Eugene V. (2007). "Compared to What? 'Cults' and 'New Religious Movements'". History of Religions. 47 (2–3): 205–220. doi:10.1086/524210. S2CID 161448414.

- ^ Oliver 2012, p. 6.

- ^ Barrett 2001, p. 24; Oliver 2012, p. 13.

- ^ Barker, Eileen (2011). "Stepping out of the Ivory Tower: A Sociological Engagement in 'The Cult Wars'". Methodological Innovations Online. 6 (1): 18–39. doi:10.4256/mio.2010.0026. S2CID 145184989.

- ^ Petersen, Jesper Aagaard (2004). "Modern Satanism: Dark Doctrines and Black Flames". In Lewis, James R.; Petersen, Jesper Aagaard (eds.). Controversial New Religions. New York: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/019515682X.003.0019. ISBN 9780195156829.

- ^ Hammer & Rothstein 2012, p. 2.

- ^ Eugene V. Gallagher, 2004, The New Religious Movement Experience in America, Greenwood Press, ISBN 0-313-32807-2

- ^ Gallagher, Eugene V., The New Religious Movements Experience in America, The American Religious Experience, 2004, ISBN 978-0-313-32807-7, p. 18.

- ^ Gallagher, Eugene V., The New Religious Movements Experience in America, The American Religious Experience, 2004, ISBN 978-0-313-32807-7, p. 17.

- ^ Affolter, Friedrich W. (2005). "The Specter of Ideological Genocide: The Bahá'ís of Iran" (PDF). War Crimes, Genocide and Crimes Against Humanity. 1 (1): 75–114. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-01-05. Retrieved 2015-01-06.

- ^ a b David Kilgour, David Matas (6 July 2006, revised 31 January 2007) An Independent Investigation into Allegations of Organ Harvesting of Falun Gong Practitioners in China Archived 2017-12-08 at the Wayback Machine (in 22 languages) organharvestinvestigation.net

- ^ a b c Barker 1989, p. 43.

- ^ Quinn, D. Michael (1992). "On Being a Mormon Historian (And Its Aftermath)". In Smith, George D. (ed.). Faithful History: Essays on Writing Mormon History. Salt Lake City: Signature Books. p. 141. Archived from the original on 2010-05-27.

- ^ Barker 1989, pp. 43–44.

- ^ "China: The crackdown on Falun Gong and other so-called "heretical organizations"". Amnesty International. 23 March 2000. Archived from the original on November 10, 2009. Retrieved 17 March 2010.

- ^ Nordlinger, Jay (25 August 2014). "Face The Slaughter". National Review. Archived from the original on 2017-06-07.

- ^ Viv Young "The Slaughter: Mass Killings, Organ Harvesting, and China's Secret Solution to Its Dissident Problem", New York Journal of Books. Archived 2015-10-19 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Ethan Gutmann (August 2014) The Slaughter: Mass Killings, Organ Harvesting and China's Secret Solution to Its Dissident Problem Archived 2016-03-02 at the Wayback Machine "Average number of Falun Gong in Laogai System at any given time" Low estimate 450,000, High estimate 1,000,000 p 320. "Best estimate of Falun Gong harvested 2000 to 2008" 65,000 p. 322.

- ^ Barbara Turnbull (21 October 2014) "Q&A: Author and analyst Ethan Gutmann discusses China's illegal organ trade" Archived 2017-07-07 at the Wayback Machine,The Toronto Star

- ^ J.K. van Baalen, The Chaos of Cults, 4th rev.ed. Grand Rapids: William Eerdmans Publishing, 1962.

- ^ Barrett 2001, pp. 104–105.

- ^ a b Barrett 2001, p. 97.

- ^ Martin, Walter Ralston. [1965] 2003. The Kingdom of the Cults (revised ed.), edited by R. Zacharias. US: Bethany House. ISBN 0764228218.

- ^ a b Michael J. McManus, "Eulogy for the godfather of the anti-cult movement", obituary in The Free Lance-Star, Fredericksburg, VA, 26 August 1989, p. 8.

- ^ "unapologetically hostile to young and developing spiritual trends" Wendy Dackson (Summer 2004). "New Religious Movements in the 21st Century: Legal, Political, and Social Challenges in Global Perspective". Journal of Church and State. 46 (3): 663. doi:10.1093/jcs/46.3.663.

- ^ Barrett 2001, p. 41.

- ^ Barrett 2001, pp. 45–46.

- ^ Barrett 2001, p. 29.

- ^ Barrett 2001, p. 30.

- ^ Barker 1989, p. 39.

- ^ Barrett 2001, p. 108.

- ^ Barker, Eileen (2009). "What Makes a Cult?". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2017-07-10.

- ^ Ed Brubaker, Fatale #21, 2014, Image, pp. 20–21

- ^ van Driel, Barend, and James T. Richardson. "Research Note Categorization of New Religious Movements in American Print Media". Sociological Analysis 1988, 49, 2:171–183

Sources

[edit]- Ashcraft, W. Michael (2005). "A History of the Study of New Religious Movements". Nova Religio: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions. 9 (1): 93–105. doi:10.1525/nr.2005.9.1.093. JSTOR 10.1525/nr.2005.9.1.093.

- Barker, Eileen (1989). New Religious Movements: A Practical Introduction. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office. ISBN 978-0-11-340927-3.

- ——— (2004). "What Are We Studying? A Sociological Case for Keeping the "Nova"" (PDF). Nova Religio: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions. 8 (1): 88–102. doi:10.1525/nr.2004.8.1.88. JSTOR 10.1525/nr.2004.8.1.88. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-03-01. Retrieved 2023-03-31.

- Barrett, David V. (2001). The New Believers: A Survey of Sects, Cults and Alternative Religions. London: Cassell & Co. ISBN 978-0-304-35592-1.

- Bromley, David G. (2004). "Whither New Religions Studies?: Defining and Shaping a New Area of Study". Nova Religio: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions. 8 (2): 83–97. doi:10.1525/nr.2004.8.2.83. JSTOR 10.1525/nr.2004.8.2.83.

- ——— (2012). "The Sociology of New Religious Movements". In Olav Hammer; Mikael Rothstein (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to New Religious Movements. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 13–28. ISBN 978-0-521-14565-7.

- Clarke, Peter B. (2006a). New Religions in Global Perspective: A Study of Religious Change in the Modern World. London; New York: Routledge.

- Clarke, Peter B., ed. (2006b). Encyclopedia of new religious movements. London; New York: Routledge. ISBN 9-78-0-415-26707-6.

- Driedger, Michael; Wolfart, Johannes C. (2018). "Reframing the History of New Religious Movements". Nova Religio: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions. 21 (4): 5–12. doi:10.1525/nr.2018.21.4.5. Archived from the original on 2021-11-01. Retrieved 2021-06-16.

- Gardner, Martin (1995), Urantia: The Great Cult Mystery, Prometheus Books, ISBN 978-1-59102-622-8

- Gibson, Lynne (2002). Modern World Religions: Hinduism – Pupil Book Core (Modern World Religions). Oxford, UK: Heinemann Educational Publishers. ISBN 978-0-435-33619-6.

- Hammer, Olav; Rothstein, Mikael (2012). "Introduction to New Religious Movements". The Cambridge Companion to New Religious Movements. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–9. ISBN 978-0-521-14565-7.

- Lewis, James R. (2004). "Overview". In James R. Lewis (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of New Religious Movements. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 1–15. ISBN 0-19-514986-6. Archived from the original on 2021-06-24. Retrieved 2021-06-16.

- Melton, J. Gordon (2004). "Toward a Definition of "New Religion"". Nova Religio: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions. 8 (1): 73–87. doi:10.1525/nr.2004.8.1.73. JSTOR 10.1525/nr.2004.8.1.73.

- ——— (2004b). "An Introduction to New Religions". In James R. Lewis (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of New Religious Movements. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 16–35. ISBN 0-19-514986-6. Archived from the original on 2021-06-24. Retrieved 2021-06-16.

- ——— (2007). "New New Religions: Revisiting a Concept". Nova Religio: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions. 10 (4): 103–112. doi:10.1525/nr.2007.10.4.103. JSTOR 10.1525/nr.2007.10.4.103.

- Oliver, Paul (2012). New Religious Movements: A Guide for the Perplexed. London; New York: Continuum. ISBN 978-1-4411-0197-6.

- Olson, Paul J. (2006). "The Public Perception of "Cults" and "New Religious Movements"". Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 45 (1): 97–106. doi:10.1111/j.1468-5906.2006.00008.x.

- Rubinstein, Murray (7 June 2023). "New Religious Movement (NRM)". Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- Robbins, Thomas (2000). "Quo Vadis the Scientific Study of New Religious Movements". Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 39 (4): 515–524. doi:10.1111/j.1468-5906.2000.tb00013.x.

Further reading

[edit]- Encyclopedias

- Barrett, David B.; Kurian, George T.; Johnson, Todd M. (2001-02-15). World Christian Encyclopedia: A Comparative Survey of Churches and Religions in the Modern World. Vol. 1–2 (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195079630.

- Chryssides, George D. (2001). Historical dictionary of new religious movements. Lanham, Md. [u.a.]: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-4095-9.

- Chryssides, George D. (2006). The A to Z of new religious movements (Rev. pbk. ed.). Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-5588-5.

- Lewis, James R.; Tøllefsen, Inga Bårdsen, eds. (2016) [2008]. The Oxford Handbook of New Religious Movements. Oxford Handbooks. Vol. 2 (2nd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-046617-6. Archived from the original on 2023-03-31.

- Mead, Frank S.; Hill, Samuel S. (1995). Handbook of Denominations in the United States. Nashville, Tenn: Abingdon Press.

- Melton, J. Gordon (1992) [1986]. Encyclopedic Handbook of Cults in America. Religious Information Series, 7 (Rev. and updated ed.). New York; London: Garland Publ. ISBN 0-8153-0502-8.

- Melton, J. Gordon (1999). Religious Leaders of America: A Biographical Guide to Founders and Leaders of Religious Bodies, Churches, and Spiritual Groups in North America (2nd ed.). Detroit, Mi: Gale Group. ISBN 0-8103-8878-2.

- Melton, J. Gordon; et al., eds. (2009) [1978]. Melton's Encyclopedia of American Religions (8th ed.). Detroit, Mi: Gale Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-0-787-69696-2. (archived)

- Partridge, Christopher, ed. (2004). Encyclopedia of New Religions: New Religious Movements, Sects and Alternative Spiritualities. Oxford: Lion.

- Monographs

- Arweck, Elisabeth and Peter B. Clarke, New Religious Movements in Western Europe: An Annotated Bibliography, Westport; London: Greenwood Press, 1997.

- Barker, Eileen and Margit Warburg, eds. (1998). New Religions and New Religiosity, Aarhus, Denmark: Aargus University Press.

- Beck, Hubert F. How to Respond to the Cults, in The Response Series. St. Louis, Mo.: Concordia Publishing House, 1977. 40 p. N.B.: Written from a Confessional Lutheran perspective. ISBN 0-570-07682-X

- Beckford, James A. (ed) New Religious Movements and Rapid Social Change, Paris: UNESCO/London, Beverly Hills & New Delhi: SAGE Publications, 1986.

- Clarke, Peter B. (2000). Japanese New Religions: In Global Perspective. Richmond : Curzon. ISBN 978-0-7007-1185-7

- Ferm, Vergilius Ture Anselm (1948). Religion in the twentieth century. New York, Philosophical Library.

- Hexham, Irving and Karla Poewe, New Religions as Global Cultures, Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press, 1997.

- Hexham, Irving, Stephen Rost & John W. Morehead (eds) Encountering New Religious Movements: A Holistic Evangelical Approach, Grand Rapids: Kregel Publications, 2004.

- Kranenborg, Reender (Dutch language) Een nieuw licht op de kerk?: Bijdragen van nieuwe religieuze bewegingen voor de kerk van vandaag/A new perspective on the church: Contributions by NRMs for today's church Published by het Boekencentrum, (a Christian publishing house), the Hague, 1984. ISBN 90-239-0809-0.

- Stark, Rodney (ed) Religious Movements: Genesis, Exodus, Numbers, New York: Paragon House, 1985.

- Chryssides, George D., Exploring New Religions, London & New York: Cassell, 1999.

- Davis, Derek H., and Barry Hankins (eds) New Religious Movements and Religious Liberty in America, Waco: J. M. Dawson Institute of Church-State Studies and Baylor University Press, 2002.

- Enroth, Ronald M., and J. Gordon Melton. Why Cults Succeed Where the Church Fails. Elgin, Ill.: Brethren Press, 1985. v, 133 p. ISBN 0-87178-932-9

- Jenkins, Philip, Mystics and Messiahs: Cults and New Religions in American History, New York: Oxford University Press, 2000.

- Kephart, William M; Zellner, W. W. (1994). Extraordinary groups: an examination of unconventional life-styles. New York: St. Martin's Press.

- Kohn, Rachael, The New Believers: Re-Imagining God, Sydney: HarperCollins, 2003.

- Loeliger, Carl and Garry Trompf (eds) New Religious Movements in Melanesia, Suva, Fiji: University of the South Pacific & University of Papua New Guinea, 1985.

- Meldgaard, Helle and Johannes Aagaard (eds) New Religious Movements in Europe, Aarhus, Denmark: Aarhus University Press, 1997.

- Needleman, Jacob and George Baker (eds) Understanding the New Religions, New York: Seabury Press, 1981.

- Possamai, Adam, Religion and Popular Culture: A Hyper-Real Testament, Brussels: P.I.E. – Peter Lang, 2005.

- Saliba, John A., Understanding New Religious Movements, 2nd edition, Walnut Creek, Lanham: Alta Mira Press, 2003.

- Staemmler, Birgit, Dehn, Ulrich (ed.): Establishing the Revolutionary: An Introduction to New Religions in Japan. LIT, Münster, 2011. ISBN 978-3-643-90152-1

- Stein, Stephen J. (2003). Communities of Dissent: A History of Alternative Religions in America. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195158253

- Thursby, Gene. "Siddha Yoga: Swami Muktanada and the Seat of Power." When Prophets Die: The Postcharismatic Fate Of New Religious Movements. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1991 pp. 165–182.

- Toch, Hans. The Social Psychology of Social Movements, Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill Company, 1965.

- Towler, Robert (ed) New Religions and the New Europe, Aarhus, Denmark: Aarhus University Press, 1995.

- Trompf, G.W. (ed) Cargo Cults and Millenarian Movements: Transoceanic Comparisons of New Religious Movements, Berlin & New York: Mouton de Gruyter, 1990.

- Wilson, Bryan and Jamie Cresswell (eds) New Religious Movements: Challenge and Response, London & New York: Routledge, 1999.