Black and tan clubs

This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2022) |

Black and Tan clubs were nightclubs in the United States in the early 20th century catering to the black and mixed-race ("tan") population.[1][2] They flourished in the speakeasy era and were often popular places of entertainment linked to the early jazz years. With time the definition simply came to mean black and white clientele.

Although aimed as a venue for people of color (who had few places to go) the liberal attitudes of the establishments usually attracted all types and were the first "gay friendly" establishments. They were certainly welcomed by a large section of society. Within wider society they were generally viewed as socially and sexually immoral (or amoral).[3] White customers may have been seen as intruders by other customers, but as paying clientele would usually be welcomed by the owners. The net result was a melting point for cultures. However, some clubs physically divided black and white inside and some did not allow the two to attend at the same hours.[4]

Purcell's So Different Cafe

[edit]Purcell's So Different Cafe at 520 Pacific Street in San Francisco was part of the Terrific Street-entertainment district, famed for its music and dance, and was home to ragtime and jazz bands.[5] It was opened by Sid LeProtti around 1910.

Cafe de Champion

[edit]On 10 July 1912 the prize fighter and heavyweight champion of the world, Jack Johnson opened the Cafe de Champion at 41 West 31st Street in the Bronzeville district of Chicago. It was one of the first truly opulent buildings to cater for African Americans and boasted features such as electric fans to cool the interior (some of the first in the city). The Chicago Tribune on the following day announced only 17 of Chicago's 120,000 coloured population did not attend the opening night party.[6] Whilst this is clearly an exaggeration, there may well have been the majority of all young black couples at the party, possibly more than 5000 persons.

The building occupied three floors. Johnson's wife Etta ran the restaurant, where the waiters all wore white gloves. There was a further private dining area on the second floor. The elaborate bar was made of mahogany. Music and dancing took place in the Pompeiian Room which was decorated in the Roman style. Johnson himself played the "bull fiddle" (Double bass) in the band.[7]

This pre-Prohibition club could sell alcohol when it first opened. It was restricted to a 1am closure but frequently breached this, calling for revocation of its license.[8]

The top floor served as accommodation to the Johnsons. Etta committed suicide in the apartment on 11 September 1912, shooting herself in the head during a night of revelry below.[9] Johnson was forced to quit the premises in November 1912 due to multiple scandals.

The Jupiter

[edit]The Jupiter club in San Francisco was opened by Jelly Roll Morton in 1917.[5] It was located in a basement on Columbus Avenue. Due to police pressure Morton left the venture in 1922.[10]

Spider Kelly's Saloon

[edit]Spider Kelly, born James Curtin, was a lightweight boxer and trainer who immigrated to San Francisco from Ireland while an adolescent.[11] Formerly the Seattle Saloon at 574 Pacific Street in San Francisco the property was bought by "Spider" Kelly in 1919 and reopened specifically as a black and tan club.[5][12] This dance hall was known as one of rowdiest clubs of Terrific Street.[13]

Black and Tan Club, Seattle

[edit]The Black and Tan Club in Seattle was founded in 1922 in the wake of Prohibition, catering for the relatively small black and mixed-race population in that city. It was held in a basement under a drug store at the junction of 12th Street and Jackson. By the onset of the Second World War the club was one of the most popular in the city and welcomed whites and Asians as well as its target clientele. Early performers in the club included Duke Ellington, Eubie Blake, Louis Jordan and Lena Horne. In the 1950s performers included Ray Charles, Charlie Parker, Count Basie and Ernestine Anderson. In 1964 the club gained notoriety as the site of a murder: being where Little Willie John stabbed Kendall Roundtree. With the demise of racial segregation in America the need for such clubs eased and the club closed in 1966.

Cotton Club

[edit]Jack Johnson's second club opened in Harlem, New York in 1920 under the name of Club Deluxe. He sold it to a local racketeer in 1923, who changed the name to Cotton Club. Ironically, despite being opened as a black and tan club, it changed to white only upon sale. It desegregated again in June 1935, however.

The Cotton Club opened during Prohibition and epitomized high-profile "speakeasies".

Plantation Club

[edit]The Plantation Club opened as a rival to the Cotton Club in December 1929 and was housed in a former Harlem dance academy.[14] It spawned much black talent, including Josephine Baker and Cab Calloway. Not a true black and tan, it focussed on black entertainers entertaining white clients. A destructive attack on the club by the Cotton Club raised little sympathy amongst the black locals. The club closed in 1940.

Cafe Society

[edit]

Cafe Society was opened by Barney Josephson (1902-1988) in a basement at 2 Sheridan Square in New York City in 1938. His singers included Billie Holiday, Lena Horne and Sarah Vaughan. Albert Ammons played piano and Big Joe Turner sang blues. Comedy was provided by Jack Gilford.[15]

In 1940, Josephson opened Cafe Society Uptown at East 58th Street.

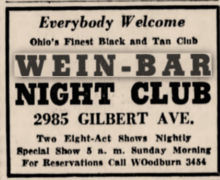

Wein Bar

[edit]The Wein Bar,[16] located in Cincinnati, Ohio was started in 1934 by Joseph Goldhagen, who during the 1920's, was active in the commercial production of illegal alcohol until the Prohibition period ended and the bar was opened. During the 1930's, the bar had multiple live performances daily, and over time, the bar evolved into an R&B live performance venue with regional and national music entertainment. Popular musicians include; Fats Waller, Lionel Hampton, Lou Rawls, James Brown and notably the formation of the James Brown funk era band (The J.B.'s) occurred during a live fundraising performance at the bar. From the early years, it was a meeting place for planning civil rights activism, organizing travel outside the region for protests events, and was an ongoing fund raising location for the NAACP. The bar was closed in 1980 after more than 40 years of operation, and was possibly the longest operating establishment that catered to the black community, its musicians, and in active support of their civil rights.

Others

[edit]Other Harlem black and tans included Connie's Inn, Small's Paradise, Connor's Club, Edmund's Cellar, and Barron Wilkin's Club (also known as Barron's Exclusive Club).[17][18] Other Chicago black and tans included the Dreamland Club, Sunset Cafe (remodeled and renamed Grand Terrance Ballroom), and Royal Gardens (later known as Lincoln Gardens).[17]

The clubs were mainly located in the "slums", that is to say, the black neighborhoods. White people attending the clubs were therefore said to be "slumming it".[19]

References

[edit]- ^ "The Devil's Music: 1920's Jazz (final film in the 4-part Culture Shock series)". WGBH PBS. Retrieved 2023-01-16.

- ^ Hill, Megan (2017-09-19). "Much-Anticipated Black and Tan Hall Should Open Any Minute Now". Eater Seattle. Retrieved 2023-01-16.

- ^ "Civil Rights in Black and Tan". 27 January 2005.

- ^ "B is for Black-and-Tan (AtoZ Challenge - Roaring Twenties)". 2 April 2015.

- ^ a b c Kamiya, Gary (2013-10-26). "Barbary Coast joint hosted jazz pioneer". SFGATE. Retrieved 2023-01-16.

- ^ Chicago Tribune 11 July 1912

- ^ Chicago Tribune 25 May 2018

- ^ Chicago Tribune,23 October 1912

- ^ Chicago Tribune 12 September 1912

- ^ Miller, Leta E. (2012). Music and Politics in San Francisco: From the 1906 Quake to the Second World War. University of California Press. p. 101. ISBN 978-0-520-26891-3.

- ^ Lang, Arne K. (2014-01-10). The Nelson-Wolgast Fight and the San Francisco Boxing Scene, 1900-1914. McFarland. pp. 34–35. ISBN 978-0-7864-9039-4.

- ^ Fleming, E. J. (2015-09-11). Carole Landis: A Tragic Life in Hollywood. McFarland. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-7864-8265-8.

- ^ Smith, James R. (2005). San Francisco's Lost Landmarks. Quill Driver Books. p. 81. ISBN 978-1-884995-44-6.

- ^ Wintz, Cary D.; Finkelman, Paul (2012-12-06). Encyclopedia of the Harlem Renaissance. Routledge. p. 1568. ISBN 978-1-135-45536-1.

- ^ New York Times 30 September 1988

- ^ "45 years a Pioneer, Wein Bar Ends and Era". Cincinnati Enquirer. February 5, 1980. p. 33. Retrieved March 19, 2022.

- ^ a b Wintz, Cary D.; Finkelman, Paul (2004). Encyclopedia of the Harlem Renaissance: A-J. Taylor & Francis. pp. 121–122. ISBN 978-1-57958-457-3.

- ^ Gottschild, Brenda Dixon (2016-04-29). Waltzing in the Dark: African American Vaudeville and Race Politics in the Swing Era. Springer. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-312-29968-2.

- ^ "The South Side - Black and Tans". Archived from the original on 2009-03-16. Retrieved 2020-12-31.