LGBT rights in Croatia

LGBT rights in Croatia | |

|---|---|

Location of Croatia (dark green) – in Europe (light green & dark grey) | |

| Status | Legal since 1977, age of consent equalized in 1998 |

| Gender identity | Changing legal gender is permitted by the law |

| Military | Allowed to openly serve[1] |

| Discrimination protections | Sexual orientation, gender identity and gender expression protections (see below) |

| Family rights | |

| Recognition of relationships | Unregistered cohabitation since 2003, Life partnership since 2014 |

| Restrictions | Constitution bans same-sex marriage since the 2013 referendum. |

| Adoption | Full adoption rights since 2022[2] |

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights in Croatia have expanded since the turn of the 21st century, especially in the 2010s and 2020s. However, LGBT people still face some legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. The status of same-sex relationships was first formally recognized in 2003 under a law dealing with unregistered cohabitations. As a result of a 2013 referendum, the Constitution of Croatia defines marriage solely as a union between a woman and man, effectively prohibiting same-sex marriage.[3] Since the introduction of the Life Partnership Act in 2014, same-sex couples have effectively enjoyed rights equal to heterosexual married couples in almost all of its aspects, except adoption. In 2022, a final court judgement allowed same-sex adoption (both stepchild and joint adoptions) under the same conditions as for mixed-sex couples. Same-sex couples in Croatia can also apply for foster care since 2020. Croatian law forbids all discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation, gender identity, and gender expression in all civil and state matters; any such identity is considered a private matter, and such information gathering for any purpose is forbidden as well.

Centre-left, centre, liberal and green political parties have generally been the main proponents of LGBT rights promulgation, while right-wing, centre-right and Christian democratic political parties and movements with ties to the Roman Catholic Church have been in opposition to or moderation of the extension of rights. In 2015, the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association (ILGA) ranked Croatia fifth in terms of LGBT rights out of 49 observed European countries, which represented an improvement compared to the previous year's position of twelfth place.[4][5] Croatia is among 11 member countries that make up an LGBT Core Group at the United Nations on Ending Violence and Discrimination.[6] Several LGBT+ related bills that codify and expand on existing rights were introduced in 2023 by the opposition, notably the We can! party (Croatian: Možemo!) and their allies. These included the legal recognition of same-sex marriage in all but name, the right to apply for foster care, the right to apply to adopt children, more inclusive IVF access, easier legal gender change, help for hate crime victims, better legal protection for LGBT+ people and legal recognition of parenthood for children adopted by same-sex couples. None of the proposed bills has passed legislation as of January 2024.[7]

LGBT history in Croatia

[edit]The Adriatic Republic of Ragusa introduced the death penalty for sodomy in 1474 as a response to stereotypical fears that Ottoman conquests in the region will lead to the spread of homosexuality.[8]

19th and 20th century

[edit]The Penal Code established on 27 May 1852 in the Habsburg Kingdom of Croatia (the first modern one in Croatian) did not specify homosexuality as a crime.[9] A subsequent draft of the new Penal Code for 1879 for the Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia suggested male homosexual acts be punished with up to five years of prison, but the draft was never formally adopted.[10]

During World War II, homosexual persons were prosecuted under various fascist regimes, but there is no record of organized persecution of homosexuals in the fascist Independent State of Croatia, whose laws did not explicitly contain a regulation directed against them.[11] The communist Yugoslav Partisans, however, issued at least one death sentence against a homosexual, Josip Mardešić, the commander of the Croatian Partisans' communication network until early 1944, when he was discovered to have had affairs with his male subordinates. Mardešić's sexual partners were not executed, only expelled from the Communist Party and reprimanded.[12][13]

Socialist Republic of Croatia

[edit]During the period when Croatia was part of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, male homosexual acts were made illegal and punishable with up to two years of prison under the Penal Code of 9 March 1951.[14] However, the repression of homosexuals in Yugoslavia effectively began immediately after the end of the war. Homosexuals, labeled by communists as "enemies of the system", were also prohibited from joining the Communist Party of Yugoslavia.[15]

This situation changed when Croatia and other republics gained more control over their own legislature. Constitutional reforms in Yugoslavia in 1974 resulted in the abolishment of the federal Penal Code, allowing every republic to create its own. The Socialist Republic of Croatia created its own Code in 1977, and decriminalized homosexual activity. The Croatian Medical Chamber removed homosexuality from its list of mental disorders in 1973 – four years before the introduction of the new Penal Code, and seventeen years before the World Health Organization did the same.[11] Even though being a member of Yugoslavia meant Croatia was a communist country, it was never under the Iron Curtain, thus making it a relatively open country that was influenced by social changes in the wider developed world.[16]

The 1980s brought more visibility to LGBT people. In 1985, Toni Marošević became the first openly gay media person, and briefly hosted a radio show on the Omladinski radio radio station that dealt with marginal socio-political issues.[17] He later revealed that he had been asked on several occasions by the League of Communists of Croatia to form an LGBT faction of the party. The first lesbian association in Croatia, the "Lila initiative", was formed in 1989, but ceased to exist a year later.[11]

Post-communist era

[edit]The 1990s brought a slowdown in terms of the progression of LGBT rights mainly as a result of the breakup of Yugoslavia followed by the Croatian War of Independence when many Croatian LGBT people, then involved in various feminist, peace and green organizations, joined the anti-war campaign within Croatia. Following Croatian independence, in 1992 the first LGBT association was officially formed, under the name of LIGMA (lezbijska i gej akcija, 'lesbian and gay action',[18] sometimes referred to in English as the Lesbian and Gay Men's Association[19]). This only lasted until 1997 as the socio-political climate of the time proved hostile to the advancement of gay rights. The most significant event that occurred in the 1990s was the equalization of the age of consent for all sexual activity in 1998 (both heterosexual and homosexual). The situation stagnated until 2000 when a new government coalition, consisting mainly of parties of the centre-left and led by Ivica Račan, took power from the HDZ after their ten-year rule.[11] The new government coalition brought attention to rights of LGBT citizens of Croatia with the introduction of the Same-sex community law in 2003.[20]

The 2000s proved a turning point for LGBT history in Croatia with the formation of several LGBT associations (with the Rijeka-based lesbian organisation LORI in 2000 and ISKORAK in 2002 being among the first); the introduction of unregistered cohabitations; the outlawing of all anti-LGBT discrimination (including recognition of hate-crime based on sexual orientation and gender identity); and the first gay pride event in Zagreb in 2002 during which a group of extremists attacked a number of marchers. Despite that, later marches drew thousands of participants without incidents.[21] Several political parties as well as both national presidents elected in 2000s have shown public support for LGBT rights, with some politicians even actively participating in Gay Pride events on a regular basis.[11]

In early 2005 the Sabor rejected a registered partnerships proposal put forward by Šime Lučin (SDP) and the independent Ivo Banac.[22] Lucija Čikeš MP, a member of the then-ruling HDZ, called for the proposal to be dropped because "the whole universe is heterosexual, from the atom and the smallest particle; from a fly to an elephant". Another HDZ MP objected on the grounds that, "85% of the population considers itself Catholic and the Church is against heterosexual and homosexual equality". However, the medical and physical professions, and the media more generally rejected these statements in opposition, warning that all the members of the Sabor had a duty to vote according to the Constitution which bans discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation.

In 2009, the governing Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ) party passed a controversial law restricting access to in vitro fertilisation (IVF) solely to married couples and heterosexual couples who could prove that they had been cohabitating for at least three years. HDZ initially attempted to pass the law restricting access to IVF solely to married couples, but due to strong public pressure HDZ amended the proposed law to allow access to IVF for non-married heterosexual couples as well. The Catholic Church actively supported the first legislative proposal, arguing that access to IVF should only be granted to married couples.[23] As HDZ is a self-declared Christian democratic party, the then Minister of Health and Social Welfare, Darko Milinović, indicated that the government took the Church's position on the matter seriously.[24][25][26][27][28]

In 2009, the European Committee on Social Rights found several discriminatory statements in a biology course textbook mandatory in Croatian schools. It ruled that the statements violated Croatia's obligations under the European Social Charter.[29]

The 2010s have been marked with a second annual gay pride event in Croatia in the city of Split, a third in Osijek, and the return in 2011 of the centre-left coalition sympathetic to gay rights after the eight-year rule by the conservative-led coalition.[11][30] The Croatian Government also introduced a Life Partnership Act which makes same-sex couples effectively equal to married couples in everything except full adoption rights.[21] In November 2010, the European Commission's annual progress report on Croatia's candidacy to the EU stated the number of homophobic incidents in Croatia provided concern, and that further effort had to be made in combating hate crime.[31] A 2010 resolution by the European Parliament expressed "concern at the resentment against the LGBT minority in Croatia, evidenced most recently by homophobic attacks on participants in the LGBT Pride parade in Zagreb; urges the Croatian authorities to condemn and prosecute political hatred and violence against any minority; and invites the Croatian Government to implement and enforce the Anti-Discrimination Law".[32]

In December 2011, the newly elected Kukuriku coalition government announced that the modernisation of the IVF law would be one of its first priorities. Proposed changes to the law would allow single women, whose infertility was treated unsuccessfully, access to IVF as well.[33] Other changes were also proposed concerning the freezing of embryos and the fertilization of eggs. The Catholic Church immediately indicated its public oppositions to these changes, stating that they had not been involved in the discussions as much as they should like to have been. The Church subsequently initiated a petition against the legislation, but the Minister of Health, Rajko Ostojić, announced that the law would be going ahead with no compromises.[34] When asked about his attitude on lesbian couples having access to IVF Ostojić said: "Gay is OK!"[35] On 13 July 2012, the new law came into force with 88 MPs voting in favour, 45 voting against, and 2 abstentions. A number of HNS MPs who are also members of the ruling coalition wanted lesbian couples to be included in the legal change as well, and expressed disappointment that their amendment was not ultimately accepted. Since the new law only allowed access to IVF to women who were either married or single and infertile, the law excluded lesbian couples.[36] However, the government justified the exclusion by arguing that the legislative change was only intended to deal with the issue of infertility.[37][38]

In July 2012, the Municipal Court in Varaždin dealt with a case of discrimination and harassment on the grounds of sexual orientation against a professor at the Faculty of Organization and Informatics at the University of Zagreb. The case was the first report of discrimination based on sexual orientation in accordance with the Anti-Discrimination Act. The court found that there had indeed been discrimination and harassment against the victim in the workplace, and the Faculty was prohibited from further hindering the victim's professional advancement.[39]

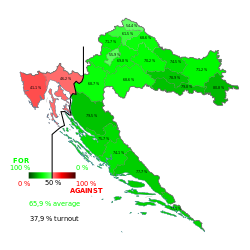

A lobby group established in 2013, "In the Name of the Family", led the call to change the Croatian national constitution so that marriage can only be defined as a union between a man and a woman. The Roman Catholic Church played a prominent role in this political campaign, and Cardinal Josip Bozanić of Zagreb issued a letter to be read in churches reminding people that "Marriage is the only union enabling procreation".[40] Subsequently, a national referendum was held on 1 December 2013 where voters approved the change. Franko Dota, a gay rights activist, criticised the results, arguing that it was intended "to humiliate the gay population, and to strike against the progress of the past decades". Stephen Bartulica, a proponent of the referendum and a professor at the Catholic University of Croatia, countered that "the vote was an attempt to show that there is strong opposition" to "gay marriage and adoption by gays". The prime minister, Zoran Milanović, was unhappy that the referendum had taken place at all, saying, "I think it did not make us any better, smarter or prettier."[21]

On 1 March 2013, the Minister for Science, Education and Sports, Željko Jovanović, announced that his ministry would begin an action to remove all homophobic content from books used in both elementary and high schools. He wanted to especially target religious education books (religious education in Croatian schools is an optional course).[41]

On 11 May 2012, Milanović announced a further expansion to the rights of same-sex couples through a new law which would replace the existing unregistered cohabitation legislation. The Sabor subsequently passed the "Life Partnership Act" on 15 July 2014. This law effectively made same-sex couples equal to heterosexual married couples in everything except adoption rights. An institution similar to step-child adoption called "partner-guardian" was created to deal with the care of children.[42][43] [44]

In March 2014, it was announced that Croatia had granted asylum for the first time to a person persecuted on the basis of their sexual orientation – a young man from Uganda who had fled the country as a result of the Uganda Anti-homosexuality Act.[45]

The first life partnership in Croatia took place in Zagreb on 5 September 2014 between two men.[46] Within a year of the Sabor passing the law 80 life partnerships were conducted. By the end of 2016 that number had risen to 174.[47][48] In October 2018, it was reported that a total of 262 life partnerships had been conducted in Croatia between September 2014 and June 2018.[49][50]

In May 2016, Zagreb Pride published the first Croatian guide for same-sex couples, LGBT parents and families named "We Have a Family!". The publication was intended for informing same-sex partners and LGBT parents and contains information about life partnership, same-sex couples rights and the possibilities of planning LGBTIQ parenting in Croatia, as well as parenting stories written based on the experience of actual Croatian LGBT parents.[51] The publication was financed by the European Union and the Government of Croatia.

In December 2016, scientists Antonija Maričić, Marina Štambuk, Maja Tadić Vujčić and Sandra Tolić published a book, I'm Not "Gay Mom", I'm Mom, in which they presented results of their research on the position of the LGBT families in Croatia, first such in the country. It provides insight into the types and characteristics of family communities, the quality of parenting, family climate and quality of relationships, a psychosocial adaptation of children, as well as experiences of stigmatization and discrimination and support in the contemporary Croatian society.[52]

The organization Rainbow Families (Croatian: Dugine obitelji) gathers LGBT couples and individuals who have or want to have children. It was organized by Zagreb Pride in 2011 as an informal group for psychosocial support led by psychologists Iskra Pejić and Mateja Popov. It was formally registered with the Ministry of Public Administration in 2017.[53] In 2018, it gathered around 20 LGBT families with children.[54] On 18 January 2018, Rainbow Families published the first picture book depicting same-sex couples with children in the Balkans, titled My Rainbow Family.[54] It was authored by Maja Škvorc and Ivo Šegota, and illustrated by Borna Nikola Žeželj. The picture book depicts thumbnails from the lives of two children: girl Ana, who has two dads, and boy Roko, who has two mothers. The aim of the picture book was to strengthen the social integration of children with same-sex parents and to promote tolerance and respect for diversity. It is intended for children of preschool age. The first edition of 500 copies was printed with the financial support of the French Embassy to Croatia and distributed for free to interested citizens and organizations. Since the entire first edition was distributed almost immediately, the organization started a crowdfunding campaign with an intention to collect funds for publishing 1000 new free hardback copies in both Croatian and English, as well as 1,000 copies of a new coloring book. In just under 24 hours, they surpassed two targeted goals and received more than $7,000 of initial $3,000 goal.[55][56]

In September 2020 gay couple Mladen Kožić and Ivo Šegota became the first same-sex foster parents in history of Croatia, after a three-year long legal battle. They became foster parents to two children.[57]

In 2022, a final court judgement allows same-sex couples to adopt children (both stepchild and joint adoptions).

Legality of same-sex sexual activity

[edit]Same-sex sexual activity was legalised in 1977[58] setting the age of consent at 18 for homosexuals and 14 for heterosexuals.[59] The age of consent was then equalised in 1998 when it was set at 14 by the Croatian Penal Code for everyone, and later raised to 15 with the introduction of a new Penal Code on 1 January 2013.[60][61] There is an exemption to this rule if the age difference between the partners is three years or less.[62]

Recognition of same-sex relationships

[edit]Same-sex relationships have legally been recognized since 2003, when the Same-sex community law was passed. The law granted same-sex partners who have been cohabiting for at least three years similar rights to those enjoyed by unmarried cohabiting opposite-sex partners in terms of inheritance and financial support. However, the right to adopt was not included, nor any other rights included under family law – instead separate legislation has been created to deal with this point. In addition it was not permitted to formally register these same-sex relationships, nor to claim additional rights in terms of tax, joint property, health insurance, pensions etc.[63]

Although same-sex marriages have been banned since the 2013 constitutional referendum, the twelfth government of Croatia introduced the Life Partnership act in 2014, which granted same-sex couples the same rights and obligations heterosexual married couples have, excluding the ability to adopt children. The ability to adopt children (both stepchild and joint adoptions) by same-sex couples has been possible since 2022 after a final court judgement.

To step into a life partnership, there are several conditions that have to be met:[64]

- both partners have to be of the same gender,

- both partners have to be at least 18 years old,

- both partners have to consent to the formation of a partnership.

Furthermore, an informal life partnership is formed if two partners are in a continuous relationship for three or more years. This type of interpersonal relationship grants the same rights a domestic partnership provides to unmarried heterosexual couples.[64]

Adoption and parenting

[edit]Since 2022, full LGBT adoption in Croatia is legal for same-sex life partners in same-sex life partnerships. On 5 May 2021, it was reported that the Administrative Court in Zagreb ruled in favour of a same-sex couple (Mladen Kožić and Ivo Šegota) being able to adopt. After initially being rejected by the Department of Social Care due to being in a Life Partnership in 2016, they sued the Ministry of Demographics, Family, Youth and Social Policy. The verdict explicitly stated that they must not be discriminated based on the fact they are a same-sex couple in a Life Partnership.[65][66] Said Ministry has decided to appeal the court ruling. On 26 May 2022, the High Administrative Court rejected the appeal, the ruling is now final.[67]

Despite the ruling by the Administrative Court, Croatia still doesn't have a national law to regulate same-sex adoptions. Protections for same-sex adoptions have so far only come from the courts, not from the Parliament or the government.

The Medically Supported Fertilization Law (Croatian: Zakon o medicinski pomognutoj oplodnji) limits access to IVF to married heterosexual couples and single women whose infertility has been unsuccessfully treated,[68] which effectively excludes same-sex couples. Contrariwise, Article 68 of the Life Partnership Act grants life partners the same rights (and obligations) married heterosexual couples have concerning health insurance and healthcare, and prohibits "adverse treatment of life partnerships" in the same areas.[64]

Partner-guardianship and parental responsibilities

[edit]A life partner who is not a legal parent of their partner's child or children can gain parental responsibilities on a temporary or permanent basis. As part of a "life partnership", the parent or parents of a child can temporarily entrust their life partner (who is not a biological parent) with parental rights. If those rights last beyond 30 days, then the decision must be certified by a notary. Under this situation, while the parental rights endure then the parent/parents and the life partner must agree collectively on decisions important for the child's well-being. In case of a dissolution of a life partnership, the partner who is not the biological parent can maintain a personal relationship with the child provided the court decides it is in the child's best interest.[69]

"Partner-guardianship" is a mechanism created under the Life Partnership Act that enables a life partner who is not a biological parent to gain permanent parental rights, and is thus similar to stepchild adoption. Such a relationship between the non-parent life partner and the child may be continued if the parent-partner dies (under the condition that the other parent has also died), is considered unknown, or has lost their parental responsibilities due to child abuse. However, the non-parent life partner can also ask for the establishment of partner-guardianship while the parent-partner is alive under the condition that the other parent is considered unknown or has lost parental responsibilities due to child abuse.[69][70]

The partner-guardian receives full parental responsibility as is the case with stepchild adoption, and is registered on the child's birth certificate as their partner-guardian. Partner-guardianship is a permanent next-of-kin relationship with all the rights, responsibilities, and legal standing as that of a parent and a child.[71][64] The first case of a partner-guardianship was reported in July 2015.[72]

Foster care

[edit]In December 2018, the Croatian Parliament passed The Act on Fostering with 72 votes for, 4 against and 6 abstainers.[73]™Croatian gay rights groups slammed a new law that blocks same sex couples from becoming foster parents, although ahead of the vote, more than 200 prominent Croatian psychologists and sociologists in a statement voiced hope that lawmakers would not be led by "prejudices and stereotypes" and deprive children of a chance to be paired with foster parents "regardless of their sexual orientation". The activists vowed to fight it in the country's top court. Afterwards, Mladen Kožić and Ivo Šegota, a gay couple aspiring to become foster parents, wrote an open letter to the government saying that by "refusing to include life partners' families in the law ... you further boosted stigma and gave it a legal framework."[74][75][76] The law came into effect on 1 January 2019.

On 20 December 2019 it was reported that aforementioned couple did win a court battle that allowed them to become foster parents. Zagreb Administrative Court annulled previous decisions including the refusals of the Center for Social Welfare and the ministry. The court decision is final, and no appeal is allowed. Their attorney Sanja Bezbradica Jelavić stated: "The court's decision is binding, and an appeal is not allowed, so this judgment is final. The written ruling has not yet arrived, but as stated during the announcement, the court accepted our argument in the lawsuit, based on Croatian regulations and the European Convention on Human Rights. As a result, the court ordered the relevant government agencies to implement the new decision in accordance with the judgment. We believe that the agencies will respect the court decision."[77]

However, despite this decision, Center for Social Welfare rejected their application for the second time. The case was put before the Constitutional Court of Croatia, and on 7 February 2020 it reached the decision that same-sex couples have the right to be foster parents. In its summary, the Constitutional Court of Croatia says: "The Constitutional Court found that the impugned legal provisions which left out ('silenced') a certain social group produces general discriminatory consequences against same-sex persons living in formal and informal life partnerships, which is constitutionally unacceptable." The president of the Constitutional Court of Croatia Miroslav Šeparović further stated:""The point of this decision is that opportunity to provide foster care service must be given to everyone under the same conditions, regardless of whether the potential foster parents are of same-sex orientation. This does not mean that they are privileged, but their foster care must be allowed if they meet the legal requirements". The Constitutional Court did not repeal the challenged legal provisions, arguing that this would create a legal loophole, but stated unequivocally that the exclusion of same-sex couples from foster care was discriminatory and unconstitutional, and provided clear instructions to the courts, social welfare centers, and other decision-making bodies regarding these issues and indicated they must not exclude applicants based on their life partnership status. Constitutional judges stressed that, despite not intervening in the legal text, "courts or other competent bodies that directly decide on individual rights and obligations of citizens in resolving individual cases are obliged to interpret and apply laws in accordance with their meaning and legitimate purpose, to make those decisions on the basis of the constitution, laws, international treaties and other sources of law." Nine judges voted for this decision, and four were against. Two out of those four were of an opinion that Sabor should be allowed to change the current Foster Care act, and the other two were of an opinion that the law did not discriminate same-sex couples.[78][79]

Gender identity and expression

[edit]Gender transition is legal in Croatia, and birth certificates may be legally amended to recognise this. Up until June 2013 the change of gender always had to be stated on an individual's birth certificate. However, on 29 May 2012 it was announced that the government would take extra steps to protect transsexual and transgender people. Under the new rules, the undertaking of sex reassignment surgery no longer has to be stated on an individual's birth certificate, thus ensuring that such information remains private. This is also the case for people who have not formally undergone sex reassignment surgery, but have nevertheless undertaken hormone replacement therapy. The change in the law was proposed by the Kukuriku coalition while they were in opposition in 2010, but was categorically rejected by the ruling right-wing HDZ at the time. The new law took effect on 29 June 2013.[80][81][82]

Discrimination protections

[edit]The first anti-discrimination directives that prohibit discrimination based on sexual orientation have been included since 2003 in the Gender Equality Law:

- Gender Equality Law (e.g. Article 6).[83]

The 2008 Anti-Discrimination Act also includes gender identity and gender expression on the list of protected categories against discrimination when it comes to access to either public and private services or to establishments serving the public. Act also applies in all other areas. It took effect on 1 January 2009.[84]

In 2023, the Constitutional Court of Croatia, in its verdict, declared that same-sex civil unions (life partnerships) are constitutional and that discrimination based on a person's sexual orientation is prohibited in the Croatian Constitution in Article 14 under the "other grounds" clause.[85]

Hate crime legislation

[edit]Since 2006, the country has had hate crime legislation in place which covers sexual orientation. The law was first applied in 2007, when a man who violently attacked the Zagreb Pride parade using Molotov cocktails was convicted and sentenced to 14 months in prison.[86][87] On 1 January 2013 new Penal Code has been introduced with the recognition of a hate crime based on a gender identity.[62]

Cooperation with the police

[edit]LGBT associations Zagreb Pride, Iskorak and Kontra have been cooperating with the police since 2006 when Croatia first recognized hate crimes based on sexual orientation. As a result of that cooperation the police have included education about hate crimes against LGBT persons in their training curriculum in 2013. In April of the same year the Minister of the Interior, Ranko Ostojić, together with officials from his ministry launched a national campaign alongside Iskorak and Kontra to encourage LGBT persons to report hate crimes. The campaign has included city light billboards in four cities (Zagreb, Split, Pula, and Osijek), handing out leaflets to citizens in those four cities, and distributing leaflets within police stations across the country.[88]

Blood donation

[edit]The regulations that govern the Croatian institute for transfusions (Hrvatski zavod za transfuzijsku medicinu) in practice restrict gay and bi men's ability to donate blood indefinitely. A 1998 bylaw on blood components had expressly banned people who practised sexual acts with the persons of the same sex from donating blood,[89] but this bylaw was rescinded with the introduction of a new Law on blood in 2006.[90] A 2007 bylaw on blood products includes among the criteria for a permanent rejection of allogeneic dose providers the generic category of "people whose sexual behavior puts them at a high risk of getting blood-borne infectious diseases",[91] and in turn the institute's blood donation restrictions on men who have sex with men, as of 2021[update], are categorized under "behaviors or activities that expose them to risk of contracting blood-borne infectious diseases".[92]

Military service

[edit]LGB persons are not banned from participation in military service. Ministry of Defence has no internal rules regarding LGB persons, but it follows regulation at the state level which explicitly prohibits discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation. Some media reports have suggested that most gay men serving in the military generally decide to keep their sexual orientation private, but there have also been reports suggesting that the Croatian Armed Forces take discrimination very seriously and will not tolerate homophobia among its personnel.[93][94]

Discrimination cases

[edit]The only known case of discrimination in the Croatian Army is the 1998 case of recruit Aldin Petrić from Rijeka. In July 1998, Petrić answered his draft summons and reported to the barracks at Pula where he told his senior officer in a private conversation that he was gay; however, that information quickly spread through the barracks, which resulted in Petrić being subjected to abuse by his fellow soldiers and other officers. Petrić repeatedly asked to be transferred to another barracks but his requests were not met. On 22 July, Petrić was dismissed from the army because of "unspecified disturbance of sexual preference" (Code F65.9 from the 1992 ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioral Disorders of the World Health Organization, which, however, has not specifically cited homosexuality as psychological disorder). Following Petrić's dismissal from Army, his parents found out about his homosexuality and expelled him from home. Petrić then sued Ministry of Defense for damages, citing "discriminatory policies, official impunity for the suffered abuse, and psychological trauma". In October 1998, the Ministry summoned Petrić once again in order for him to complete his military service which he refused fearing for his life. Afterwards Petrić sought and received political asylum in Canada.[95][96]

There have been other attacks on LGBT persons, the last one, in 2021. In Split, a representative of the LGBT community was beaten, when he decided to swim in the sea. Two people attacked him, ran away and left him injured. The mayor of Split also reacted, strongly condemning the attack.[97]

Public opinion

[edit]The 2010 European Social Survey found that 38% of Croatians agreed with the statement that "gay men and lesbians should be free to live their own lives as they wish".[98]

A poll in June 2011 showed that 38.3% of citizens supported the holding of gay pride events, while 53.5% remained opposed. However, a majority (51.3%) did not believe it was right to ban such events – while 41,2% thought they should be.[99]

A June 2013 opinion poll suggested that 55.3% stated would vote yes in an upcoming referendum to constitutionally define marriage as a union between a man and a woman; with 31.1% voting no. However, in the event, almost 40% of the national population decided not to participate in the referendum.[100]

A poll from November 2013 revealed that 59% of Croats think that marriage should be constitutionally defined as a union between a man and a woman, while 31% do not agree with the idea.[101]

After the Life Partnership Act was passed in 2014, the opposition and groups opposed to LGBT rights claimed many registrars will wish to be exempted from performing life partnerships at registrars offices, and that private businesses such as florists, bakers or wedding planners will be forced to provide services to gay and lesbian couples. The deputy head of Zagreb City Office for General Administration Dragica Kovačić claimed no cases of registrars wishing to be exempted is known. There are 30 registrars in the City of Zagreb in charge of marriages and life partnerships, and at the registrars' meeting nobody raised an issue. Additionally, a survey was conducted in which private businesses were randomly phoned, asking whether they would refuse to provide services to gay and lesbian couples. Every business surveyed stated they would offer their services to those couples.[102][103]

A survey of 1,000 people conducted in 2014 showed that 45.4% of respondents are strongly against and 15.5% are mainly against the legalisation of same-sex marriage in Croatia. 10.1% were strongly in favour, 6.9% mostly in favour, and 21.2% were neutral.[104]

A survey conducted during the presidential campaign in December 2014 by the daily newspaper Večernji list found that 50.4% of people thought that the future president should support the current level of LGBT rights in Croatia, while 49.6% thought they should not.[105]

Eurobarometer Discrimination in the EU in 2015 report concluded the following: 48% of people in Croatia believe that gay, lesbian, and bisexual people should have the same rights as heterosexual people, and 37% of them believe same-sex marriages should be allowed throughout Europe.[106]

When asked about having a gay, lesbian or bisexual person in the highest elected political position results were as follows: 40% of the respondents were comfortable with the idea, 13% moderately comfortable, 6% indifferent, 38% uncomfortable, and 3% did not know. When asked the same question about transgender or transsexual person results were as follows: 33% were comfortable with the idea, 15% moderately comfortable, 40% uncomfortable, 6% indifferent, and 5% did not know.

Furthermore, when asked how they would feel if one of their colleagues at work were gay, lesbian or bisexual results were as follows: 48% respondents felt comfortable about the idea, 11% moderately comfortable, 31% uncomfortable, 5% indifferent, 4% said it depends, and 1% did not know. When it comes to working with a transgender or transsexual person results were as follows: 44% felt comfortable with the idea, 12% moderately comfortable, 31% uncomfortable, 6% were indifferent, 3% it would depend, and 4% did not know.

That a transgender or transsexual person should be able to change their civil documents to match their inner gender identity was agreeable to 44%, disagreeable to 39%, and 17% did not know.

64% of respondents agreed that school lessons and material should include information about diversity in terms of sexual orientation, and 63% agreed the same about gender identity.

In May 2016 ILGA published a survey about attitudes towards LGBT people conducted in 53 UN members (12 of those were European countries, including Croatia). When asked whether homosexuality should be a crime, 68% of people in Croatia strongly disagreed with that (second highest percentage after the Netherlands where 70% of people strongly disagreed), 4% somewhat disagreed, 19% were neutral, 4% somewhat agreed, and 5% strongly agreed (the lowest percentage of people who strongly agreed among European countries included in the survey). Furthermore, when asked whether they would be concerned about having an LGBT neighbor, 75% of people said they would have no concerns, 15% would be somewhat uncomfortable, and 10% very uncomfortable.[107]

A poll by Pew Research Center published in May 2017 estimated that 31% of Croatians are in favour of same-sex marriage, while 64% oppose the idea. Support was higher among non-religious people (61%) than among Catholics (29%). Younger people are more likely than their elders to favour legal gay marriage (33% vs. 30%).[108][109]

The 2023 Eurobarometer found that 42% of Croatians thought same-sex marriage should be allowed throughout Europe, and 39% agreed that "there is nothing wrong in a sexual relationship between two persons of the same sex". Furthermore, 35% of respondents agreed with the statement that "lesbian, gay, bisexual people should have the same rights as heterosexual people (marriage, adoption, parental rights)", with 60% still opposed.[110]

Living conditions

[edit]The capital city Zagreb is home to the biggest gay scene, including gay clubs and bars, plus many other places frequently advertised as gay-friendly. Zagreb is also home to the first LGBT centre in Croatia, and the "Queer Zagreb" organization, that among many other activities promotes equality through the Queer Zagreb festival, and Queer MoMenti (an ongoing monthly film program dedicated to LGBT cinema).[111] Croatia's second LGBT centre was officially opened in Split on 24 May 2014, and the third one in Rijeka on 16 October 2014 called LGBTIQ+ Druga Rijeka.[112][113] Other places that host LGBT parties, and are home to gay-friendly places such as bars, clubs, and beaches are Rijeka, Osijek, Hvar, Rab, Rovinj, Dubrovnik etc.[114][115][116][117][118]

LGBT prides and other marches

[edit]Zagreb Pride

[edit]

The first pride in Croatia took place on 29 June 2002 in the capital city of Zagreb. Public support is growing and number of participants is also increasing rapidly year after year, but the marches have also experienced violent public opposition.[119] In 2006, the march had a regional character, aimed at supporting those coming from countries where such manifestations are expressly forbidden by the authorities. The 2011 manifestation was the biggest Pride rally in Croatia at the time, and took place without any violent incidents. It was also reported that the number of policemen providing security at the event was lower than had been the case in previous years. As of summer 2019, the 2013 event was the biggest one so far, with 15,000 participants.[120][121][122][123]

Split Pride

[edit]The first LGBT pride in Split took place on 11 June 2011. However, the march proved problematic as official security was not strong enough to prevent serious incidents, as a result of which LGBT attendees had to be led to safety. Several hundred anti-gay protesters were arrested, and the event was eventually cancelled.[124] Soon after the event, sections of the national media voiced supported for LGBT attendees, calling on everyone to "march in the upcoming Zagreb Pride".[125] On 9 June 2012, several hundred participants marched in Rijeka, the third largest city in Croatia. The march was organised to support Split Pride.[126] A second attempt at holding an event in 2012 was more successful, after receiving public support from the Croatian media, national celebrities, and politicians. Five ministers from the government and other public figures participated. In 2013, the march went ahead without a single incident, and it was the first time in Croatia that the mayor of the city participated.[127][128][129][130][131][132][133]

Osijek Pride

[edit]The first LGBT pride march in Osijek took place on 6 September 2014. It was organized by the Osijek LGBT association LiberOs. There were no incidents, and over 300 people attended. The Minister of the Economy, as well as Serbian and Greek LGBT activists attended.[134]

Karlovac Pride

[edit]The first pride in the city of Karlovac, organized by Marko Capan, took place on 3 June 2023.[135] The mottos of the first Karlovac Pride were "Karlovac is different and open" and "Karlovac is tolerant and inclusive."[136] A dozen of citizens were gathered and the event went without any incidents.[136] The second Karlovac Pride was held on 8 June 2024. It was the first Pride to also feature a march through the city centre.[137]

Pula Pride

[edit]The first Pride in Pula was organized by Udruga Proces and held on 22 June 2024.[138] Around 500 people were gathered for the event.[139] The event was also atended by Filip Zoričić, the mayor of Pula.[140]

Other marches

[edit]

On 27 May 2013, around 1,500 participants in Zagreb marched in support of marriage equality from the park of Zrinjevac to St. Mark's Square, the seat of the Croatian Government, Croatian parliament, and the Constitutional Court of Croatia.[141] On 30 November 2013, one day before the referendum took place, around a thousand people marched in the city of Zagreb in support of marriage equality. Marches of support also took place in Pula, Split, and Rijeka gathering together hundreds of people.[142]

Balkans Trans Inter March

[edit]The first ever Trans Inter march in the Balkans took place in Zagreb on 30 March 2019. Around 300 people marched through the streets of Zagreb calling for better protection of intersex children, and general end to discrimination. Guest from Slovenia, Serbia, Romania, Germany, United Kingdom, Switzerland, and Bosnia and Herzegovina joined the march. It was organized by Trans Aid, Trans Network Balkans, and Spektra. The march took place without any incidents.[143]

Politics

[edit]Proponents of LGBT rights

[edit]

The former Croatian President, Ivo Josipović, has given strong support to full LGBT rights, along with several other popular celebrities and centre-left political parties such as the Social Democratic Party of Croatia (SDP), the Croatian People's Party-Liberal Democrats (HNS), the Croatian Social Liberal Party (HSLS), ORaH, and the Labour Party. After Josipović was elected, he met with LGBT associations several times. On 1 June 2012, he published a video message giving support to the 2012 Split Pride and the further expansion of LGBT rights. He also condemned the violence at the 2011 Split Pride, calling it unacceptable and arguing that the next Split Pride should not experience the same scenario.[144] In October 2013 at a reception at the Presidential Palace he welcomed the newly appointed Finnish ambassador and his life partner to Croatia.[145][146]

Vesna Pusić, a member of HNS, is very popular within the Croatian LGBT community. She has been active in improving LGBT rights while being a member of successive governments. A former member of the SDP, current president of ORaH and a former Minister for Environment and Nature Protection in the Kukuriku coalition Mirela Holy has also been a notable long-time supporter of LGBT rights, and has participated in every LGBT Pride event so far.[147]

Other supporters of LGBT rights in Croatia are Rade Šerbedžija, Igor Zidić, Slavenka Drakulić, Vinko Brešan, Severina Vučković, Nataša Janjić, Josipa Lisac, Nevena Rendeli, Šime Lučin, Ivo Banac, Furio Radin, Darinko Kosor, Iva Prpić, Đurđa Adlešič, Drago Pilsel, Lidija Bajuk, Mario Kovač, Nina Violić, former Prime Minister Ivica Račan's widow Dijana Pleština, Maja Vučić, Gordana Lukač-Koritnik, pop group E.N.I. etc.[148]

Damir Hršak, a member of the Labour party, who has publicly spoken about his sexual orientation and has been involved in LGBT activism for years, is the first openly gay politician to become an official candidate for the first European Parliament elections in Croatia, held in April 2013. He had criticized the current coalition government for not doing enough for the LGBT community, and said that his party would not make concessions, and is in favour of same-sex marriage.[149][150][151]

Conservatives such as Ruža Tomašić have also indicated that same-sex couples should have some legal rights. The Croatian President Kolinda Grabar-Kitarović while against same-sex marriage, did indicate her support for the Life Partnership Act praising it as a good compromise. She also included sexual minorities in her inaugural speech, and said she would support her son if he was gay.[152][153] During the referendum, the conservative former Prime Minister, Jadranka Kosor, voted in favour of presenting the issue before the Constitutional Court, and against the proposed Constitutional change. This was a change from her previous position on homosexuality and same-sex marriage where she had been known for being against the expansion of LGBT rights, and subsequently voted "homophobe of the year" in 2010 by visitors of the website "Gay.hr" after stating that homosexuality is not natural, and that same-sex marriages should never be legal.[154] She also supported the Life Partnership Act.[155][156][157][158]

On 16 June 2011, 73 professors and associates of Zagreb Faculty of Law signed a statement initiated by the professor Mihajlo Dika, in which they expressed their full support for 2011 Zagreb Pride, and their support for the authorities in preventing and sanctioning behavior endangering equality and fundamental rights and freedoms of Croatian citizens effectively and responsibly. They also condemned hooligans that attacked the participants of the 2011 Split Pride.[159][160]

In February 2019, a new left-wing and green political party formed by local green and leftist movements and initiatives called We Can! – Political Platform appeared on the political scene. The party has expressed support for full LGBT rights. In 2020 the party won seats in Sabor, and after the 2021 local elections in Zagreb they became the largest political party in the Zagreb Assembly, winning 23 seats in total. Their mayoral candidate, Tomislav Tomašević won a landslide victory on May 31. He participated in Zagreb Pride in the past, but in 2021 for the first time as a mayor, which was also the first time a mayor of Zagreb attended the Pride.[161][162]

Opponents of LGBT rights

[edit]

The largest conservative party in Croatia, the Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ), remains opposed to LGBT rights. HDZ MPs voted against the proposed law on unregistered cohabitations, and against the Life Partnership Act.[163] Since Croatian independence, HDZ has managed to form a majority in the Sabor on its own or with coalition partners in 6 out of 8 Parliamentary elections (1992, 1995, 2003, 2007, 2015, 2016). The party has, nevertheless, enacted several laws that ban discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity as part of the negotiation process prior to the accession of Croatia to the European Union.[164] The Croatian Democratic Alliance of Slavonia and Baranja (HDSSB), a regionalist and right wing populist party formed in 2006 is also opposed to LGBT rights. During the Parliamentary debate on the Life Partnership Act, Dinko Burić, HDSSB MP stated his opposition to the law: "For us, being gay is not ok!" He also added that this is his party's official stand on LGBT rights. HDSSB MPs supported the 2013 referendum by having the word FOR on top of their laptops in Parliament.[165][166] Contrary to that, the president of HDSSB, Dragan Vulin, expressed his support for equal rights for same-sex couples in everything except adoption during the 2016 parliamentary election campaign.[citation needed]

Ruža Tomašić, leader of the Croatian Conservative Party has expressed her opposition to same-sex marriage on the grounds that Croatia is a majority Catholic country, but at the same time expressed her support for same-sex couples to receive equal rights to married couples in everything except adoption.[167] Her former deputy from the HSP Dr. Ante Starčević, Pero Kovačević, said that the 19th century Croatian politician Ante Starčević after whom the party has been named would not have opposed LGBT rights, and would have supported same-sex marriage. This was said in response to the youth-wing of the party organizing an anti-gay protest. The group later published an official letter expressing outrage to Kovačević's opposition to the protest.[168]

The Roman Catholic Church in Croatia has also been an influential and vocal opponent to the extension of LGBT rights in the country. After the first LGBT Pride in Split in 2011 some Catholic clergy even attempted to explain and justify the violence that had occurred during the Pride march. Dr. Adalbert Rebić argued that injured marchers had "got what they were asking for".[169] Meanwhile, Ante Mateljan, a professor in the Catholic Theology College, openly called for the lynching of LGBT marchers.[170]

The Catholic Church has also engaged at a political level, notably in providing public and vocal support for the 2013 referendum to define marriage in Croatia (and thus effectively reinforcing the existing prohibition on marriage between two people of the same gender). It was actively involved in collecting signatures for the petition to force a constitutional change. Cardinal Josip Bozanić encouraged support for the proposed constitutional amendment in a letter read out in all churches where he singled out heterosexual marriage as being the only union capable of biologically producing children, and thus worthy to be recognised.[171][172][173][174]

A conservative group "In the Name of the Family", formed in 2013, was the initiator of the 2013 referendum. The group opposes same-sex marriage, and any other form of recognition for same-sex unions. The most prominent member of the group, Željka Markić, opposed the Life Partnership Act claiming it was same-sex marriage under a different name, and thus a violation of the Constitution. She argued that the partner-guardianship institution proved most problematic under law. The Minister of Administration, Arsen Bauk, responded that the government would not be changing the law on this point, while giving a reminder that the Constitutional court had made clear that defining marriage as a union between a man and a woman in the Constitution must not have any negative effects on any future laws on recognising same-sex relationships (if not marriage).[175][176][177]

LGBT tourism

[edit]Croatia is a major tourist centre. Around 200,000 LGBT tourists visit Croatia annually. Destinations such as Dubrovnik, Hvar, Rab, Krk, Rovinj, Rijeka and Zagreb are advertised as gay-friendly.[178]

The city of Rab has been a popular destination among gay tourists since the 1980s, and in 2011 it has officially become the first gay-friendly destination to advertise itself as such in Croatia. Director of the Rab Tourist Board Nedjeljko Mikelić stated: "Our slogan is – Happy island, and our message is happiness and holding hands, so feel free to hold hands whether you are a same-sex couple, a heterosexual couple, a mother and a daughter, a couple in love. Nothing negative will happen to you on this island, and you will be happy."[178] In July 2008 a gay couple from South America married in Hvar.[179] In June 2012, the Croatian Minister of Tourism Veljko Ostojić welcomed all gay tourists to Croatia, and supported Split Pride.[180][181][182][183]

On the Gay European Tourism Association (GETA) website there are more than 50 gay and gay-friendly hotels and destinations in Croatia.[184]

Summary table

[edit]| Same-sex sexual activity legal | |

| Equal age of consent (15) | |

| Anti-discrimination laws in employment | |

| Anti-discrimination laws in the provision of goods and services | |

| Anti-discrimination laws in all other areas | |

| Anti-discrimination laws covering gender identity or expression in all areas | |

| Same-sex marriage | |

| Recognition of same-sex couples | |

| Stepchild adoption by same-sex couples | |

| Joint adoption by same-sex couples | |

| Adoption by a single LGBT person | |

| LGB people allowed to serve openly in the military | |

| Right to change legal gender | |

| Gender self-identification | |

| Homosexuality declassified as an illness | |

| Access to IVF for lesbian couples | |

| Conversion therapy banned by law | |

| Commercial surrogacy for gay male couples | |

| MSMs allowed to donate blood |

See also

[edit]- Human rights in Croatia

- List of LGBTQ organizations in Croatia

- LGBT rights in Europe

- LGBT rights in the European Union

References

[edit]- ^ Orhidea Gaura (26 October 2010). "Biti gay u Hrvatskoj vojsci" [Being gay in Croatian Army] (in Croatian). Nacional. Archived from the original on 11 January 2013. Retrieved 24 July 2012.

- ^ "Konačno i pravomoćna presuda: Istospolni partneri mogu ravnopravno posvajati djecu".

- ^ "BBC News – Croatians back same-sex marriage ban in referendum". BBC News. 2 December 2013.

- ^ "ILGA-Europe Annual Review of the Human Rights Situation of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex People in Europe 2015" (PDF). ILGA-Europe. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 May 2015. Retrieved 1 January 2018.

- ^ "Pride Event Calendar". ILGA-Europe. Archived from the original on 13 May 2016. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- ^ "LGBT Core Group at U.N. on Ending Violence and Discrimination". Archived from the original on 17 March 2016.

- ^ "MOŽEMO! Predstavio paket mjera "Ravno do ravnopravnosti!" za unapređenje prava LGBTIQ osoba".

- ^ Dejan Djokić (2023). A Concise History of Serbia. Cambridge University Press. p. 117. ISBN 978-1-107-02838-8.

- ^ Silović, Josip (1921). Kazneni zakon o zločinstvih, prestupcih i prekršajih od 27. svibnja 1852, sa zakoni od 17. svibnja 1875. Retrieved 23 January 2014.

- ^ Derenčin, Marijan; Matić, Željko (1997). Osnova novoga kaznenoga zakona o zločinstvih i prestupcih za kraljevine Hrvatsku i Sloveniju 1879, p. 59. Croatiaprojekt. ISBN 9789536321032. Retrieved 23 January 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f "Povijest LGBTIQ aktivizma u Hrvatskoj" [History of LGBTIQ activism in Croatia] (in Bosnian). Lgbt-prava.ba. Archived from the original on 2 December 2013. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- ^ "Smrt fašizmu i gayevima: Partizanski kapetan Mardešić '44. strijeljan je zbog homoseksualizma". Jutarnji.hr. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 11 May 2014.

- ^ Franko Dota Punishing homosexuals in the Yugoslav Anti-fascist Resistance Army (2019) pp. 136–138 "The sentence of Josip Mardešić is the only ruling for male homosexuality pronounced by a Yugoslav Partisan court martial I have thus far been able to find. Without at least a few more similar sentences, it is impossible to determine how consistent the Partisans were in punishing homosexuality... The most important fact to stress is that Mardešić was punished so drastically because of his position and rank. As the commander of the whole Croatian Partisan army communication network, he had knowledge of all, including the most sensitive, information..."

- ^ "Krivični zakonik". Overa. Archived from the original on 3 November 2013.

Za protivprirodni blud između lica muškog pola, učinilac će se kazniti zatvorom do dve godine

- ^ "Homoseksualci su za partizane bili 'nakaze koje treba strijeljati'" [Homosexuals were 'freaks that need to be shot' for partisans]. Jutarnji List (in Croatian). 28 June 2009. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ^ Srzić, Ante (4 October 2017). "Pitali smo predsjednicu zašto i dalje tvrdi da je Hrvatska bila iza željezne zavjese" [We asked the President why she insists on claiming that Croatia was under the Iron Curtain]. tportal (in Croatian). Retrieved 7 February 2018.

- ^ "Kolege, prijatelji i obitelj se na Mirogoju oprostili od poznatog novinara Tonija Maroševića" [Colleagues, friends and family on Mirogoj say goodbye to famous journalist Toni Marošević]. Index.hr (in Croatian). 20 March 2013. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- ^ Bilić, Bojan (2020). Trauma, Violence, and Lesbian Agency in Croatia and Serbia: Building Better Times. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 74. ISBN 9783030229603.

- ^ Desnica, Mica; Knezevic, Durda (2018). "Something Unexepcted". In Renne, Tanya (ed.). Ana's Land: Sisterhood in Eastern Europe. New York: Routledge. p. 202. ISBN 9780429970849.

- ^ "Zakon o istospolnim zajednicama" [Same-sex community law]. Narodne novine (in Croatian). 22 July 2003. Retrieved 1 January 2018.

- ^ a b c Dan Bilefsky (2 December 2013). "Croatian Government to Pursue Law Allowing Civil Unions for Gay Couples". - The New York Times. Retrieved 30 December 2016.

- ^ "Yes, I take you, George Anthony as life partner". Slobodna Dalmacija (in Croatian). Retrieved 31 May 2012.

- ^ "HBK:The gift of life must be actualized in marriage" (in Croatian). Križ života. Archived from the original on 7 December 2009. Retrieved 31 May 2012.

- ^ ISTAKNUO, MILINOVIĆ (11 March 2009). "The government observes the Church's position on artificial insemination". Vijesti (in Croatian). Retrieved 31 May 2012.

- ^ "The state of social justice and Christian values" (in Croatian). HDZ. Archived from the original on 2 June 2012. Retrieved 31 May 2012.

- ^ "Artificial insemination only in marriage". RTL Televizija (in Croatian). 28 May 2009. Archived from the original on 10 January 2014. Retrieved 31 May 2012.

- ^ "Revised Law on Artificial Insemination". RTL Televizija (in Croatian). 16 July 2009. Archived from the original on 10 January 2014. Retrieved 31 May 2012.

- ^ Martić, Petra (17 July 2009). "Common-law partners right to artificial insemination". Deutsche Welle (in Croatian). Retrieved 31 May 2012.

- ^ "ECSR decision on the merits in case no. 45/2007 – para. 60" (PDF). Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- ^ "Citanka LGBT Ljudskih Prava" (PDF). Soc.ba. Retrieved 1 January 2018.

- ^ Croatia 2010 PROGRESS REPORT (PDF). European Commission. 2010. p. 52.

- ^ "Texts Adopted". European Parliament. Retrieved 31 May 2012.

- ^ "Usvojen Zakon o medicinski potpomognutoj oplodnji". Novi list (in Croatian). 13 July 2012. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- ^ Darko, Pavičić (16 April 2012). "Crkve ujedinjene u 'vjerskom ratu' protiv premijera i ministra zdravlja" [Churches united in a 'religious war' against the Prime Minister and Minister of Health]. Večernji list (in Croatian). Retrieved 31 May 2012.

- ^ Knežević, Ivana (28 March 2012). "Ostojić: Gay is O.K., na potpomognutu oplodnju mogu sve žene i parovi" [Ostojic: Gay is OK, assisted reproduction for all women and couples]. Vjesnik (in Croatian). Archived from the original on 29 March 2012. Retrieved 31 May 2012.

- ^ "Zakon o umjetnoj oplodnji diskriminira lezbijke i neudane!". tportal.hr. 13 November 2012. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- ^ "Sa 88 glasova za i 45 protiv Sabor donio Zakon o MPO-u!". tportal.hr. 13 July 2012. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- ^ "Početna". lori.hr. Retrieved 17 August 2013.[failed verification]

- ^ "Croatia" (PDF). Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- ^ "Bozanić: Pozovite vjernike da izađu na referendum i ponosno zaokruže 'ZA'!". Dnevnik.hr. 20 November 2013. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ^ "Vlada udžbenike iz vjeronauka mijenja da zaštiti gay osobe". Jutarnji.hr. 13 August 2013. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- ^ "LORI" (in Croatian). Retrieved 31 May 2012.

- ^ Šurina, Maja (11 May 2012). "Gays can not have the same rights, we are a Catholic country!". Vijesti (in Croatian). Retrieved 31 May 2012.

- ^ "POVIJESNA ODLUKA U SABORU Istospolni će parovi od rujna imatiista prava kao i bračni partneri -Jutarnji List". Jutarnji.hr. 15 July 2014. Archived from the original on 17 July 2014. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- ^ "SPASILI GA OD PROGONA Mladiću iz Ugande prvi politički azil u Hrvatskoj jer je gay – Jutarnji.hr". Archived from the original on 7 April 2016. Retrieved 20 March 2014.

- ^ "U Zagrebu je sklopljen prvi gay brak: Ministar Bauk mladoženjama darovao kravate" [First gay marriage in Zagreb: Minister Bauk gifted ties to grooms] (in Croatian).

- ^ ired (16 July 2015). "Životno partnerstvo godinu dana poslije – u emocijama i brojkama – CroL". Crol.hr. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- ^ "174 Couples Entered into Same-Sex Civil Unions in Croatia". 22 February 2017.

- ^ "Croatian activists to challenge law barring gay couples from fostering children". France 24 International News. 12 November 2018.

- ^ Komunikacije, Neomedia. "Ne želimo našu ljubav skrivati "u ormaru": Doznajte koliko je istospolnih brakova dosad sklopljeno u Hrvatskoj / Novi list". www.novilist.hr (in Croatian). Retrieved 3 July 2019.

- ^ G.K. "'Imamo obitelj!': stvarne priče i iskustva LGBT roditelja iz Hrvatske – CroL". www.crol.hr.

- ^ "KAKO ŽIVE HRVATSKE GAY OBITELJI I KAKO DJECA DOŽIVLJAVAJU SVOJE GAY RODITELJE 'Kad sam doznao, meni je to bilo, ono, nešto posebno u vezi mame'". 2 December 2016.

- ^ "Dugine obitelji". Dugine obitelji.

- ^ a b "VIDEO Predstavljena prva hrvatska slikovnica o istospolnim obiteljima, pogledajte kako izgleda".

- ^ "Prikuplja se novac za novih 1.000 primjeraka slikovnice Moja dugina obitelj".

- ^ "Veliki uspjeh crowdfounding kampanje, tiskat će se na tisuće komada hrvatske gay slikovnice".

- ^ "Gay couple in Croatia become first same-sex foster parents in the country". gcn.ie. 9 September 2020. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- ^ "Where is it illegal to be gay?". BBC News. 10 February 2014. Retrieved 13 February 2014.

- ^ Gerstner, David A. (March 2006). Routledge David A. Gerstner: International Encyclopedia of Queer Culture, Routledge, 2012. Routledge. ISBN 9781136761812. Retrieved 23 January 2014.

- ^ "The House of Representatives of Croatia". Narodne Novine (in Croatian). Retrieved 31 May 2012.

- ^ "Kazneni zakon". Zakon.hr. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- ^ a b "Ovo su promjene koje stupaju na snagu od 1. siječnja 2013. – Vijesti – hrvatska – Večernji list". Vecernji.hr. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- ^ "ZAKON O ISTOSPOLNIM ZAJEDNICAMA – N.N. 116/03". Poslovniforum.hr. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- ^ a b c d "Zakon o životnom partnerstvu osoba istog spola".

- ^ "Sud odlučio da istospolni bračni par koji je ministarstvo odbilo ipak smije udomiti dijete". Telegram.hr. 19 December 2019.

- ^ "Povijesna odluka Upravnog suda: životni partneri u Hrvatskoj odsad se mogu prijaviti za posvajanje djece". Crol. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ^ "Sud donio povijesnu odluku: Istospolne partnere više se ne smije diskriminirati kod posvajanja djece [Court reaches historic decision, same-sex couples can no longer be discriminated regarding adoption]". Jutarnji list (in Croatian). 26 May 2022. Retrieved 26 May 2022.

- ^ "Zakon o medicinski pomognutoj oplodnji" [Medically Supported Fertilization Law]. Zakon.hr (in Croatian). Retrieved 11 February 2018.

- ^ a b Ponoš, Tihomir (29 October 2013). "Zakon o životnom partnerstvu: Partneru u istospolnoj zajednici skrb o djetetu". Novi list. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ^ "Prvom istospolnom paru odobrena partnerska skrb nad djetetom" [First same-sex couple granted partner-guardianship over child]. tportal.hr (in Croatian). 13 July 2015. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ^ Romić, Tea (10 July 2014). "Papa je rekao da biti gay nije grijeh. Zato, gospodine, katekizam u ruke!". Večernji list. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- ^ "U Hrvatskoj dodijeljena prva partnerska skrb – CroL". Crol.hr. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- ^ "Zakon o udomiteljstvu prošao, gay parovi neće moći udomiti". www.24sata.hr (in Croatian). 7 December 2018. Retrieved 3 July 2019.

- ^ "Gay smo i htjeli smo udomiti djevojčicu, ali nisu nam dali..." www.24sata.hr (in Croatian). 29 November 2018. Retrieved 3 July 2019.

- ^ "Gay par: 'Htjeli smo udomiti dijete, zato sad tužimo državu'". www.24sata.hr (in Croatian). 8 December 2018. Retrieved 3 July 2019.

- ^ "Croatian activists to challenge law barring gay couples from fostering children". France 24. 11 December 2018. Retrieved 3 July 2019.

- ^ "Croatia Court Decision: Gay Couple Allowed to be Foster Parents". www.total-croatia-news.com. 20 December 2019.

- ^ "Croatia Constitutional Court: Same Sex Couples Can Be Foster Parents". www.total-croatia-news.com. 7 February 2020.

- ^ "Šeparović: Ustavni sud je naredio da se istospolnim osobama omogući udomljavanje". tportal.hr.

- ^ Barilar, Suzana (29 May 2012). "Transgendered to receive new birth certificates". Jutarnji List (in Croatian). Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 31 May 2012.

- ^ "Moći će uzeti novo ime i prije promjene spola". Jutarnji.hr. 13 August 2013. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- ^ "History of hidra.hr". www.ivisa.com.

- ^ "Zakon o ravnopravnosti spolova" [Gender Equality Law]. Narodne novine (in Croatian). 22 July 2003. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- ^ "Anti-Discrimination Act" (in Croatian). Narodne-novine. 21 July 2008. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- ^ "Ustavni sud: Zakon o životnom partnerstvu osoba istog spola nije suprotan odredbama Ustava". 28 December 2023.

- ^ "Croat charged with hate crime for attempting to attack gay parade". International Herald Tribune. 30 October 2007. Archived from the original on 11 June 2008.

- ^ "Eight Arrested Amid Violence at Croatian Pride March". Advocate. 10 July 2007. Retrieved 9 April 2021.

- ^ "Ministar Ostojić pozvao LGBT osobe da prijavljuju zločine iz mržnje". CroL.hr. 16 April 2013. Archived from the original on 11 January 2016. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- ^ Ministry of Health (Croatia) (16 December 1998). "Pravilnik o krvi i krvnim sastojcima" [Bylaw for blood and its contents]. Narodne novine (in Croatian) (14/1999). Retrieved 18 July 2011.

Članak 16. Trajno se isključuju kao davatelji krvi: [...] osobe sa homoseksualnim ponašanjem [...]

- ^ Croatian Parliament (17 July 2006). "Zakon o krvi i krvnim pripravcima" [Law on blood and blood products]. Narodne novine (in Croatian) (79/2006).

Članak 48. Stupanjem na snagu pravilnika iz članka 46. ovoga Zakona prestaje važiti Pravilnik o krvi i krvnim sastojcima (»Narodne novine«, br. 14/99.).

- ^ Ministry of Health (Croatia) (23 July 2007). "Pravilnik o posebnim tehničkim zahtjevima za krv i krvne pripravke" [Bylaw on special technical requirements for blood and blood products]. Narodne novine (in Croatian) (80/2007). Retrieved 18 July 2011.

2.1. Mjerila za trajno odbijanje davatelja alogeničnih doza [...] Osobe koje njihovo seksualno ponašanje dovodi u visoki rizik dobivanja zaraznih bolesti koje se mogu prenositi krvlju.

- ^ "O darivanju" [About donating] (in Croatian). Croatian institute for transfusions / Hrvatski zavod za transfuzijsku medicinu. Archived from the original on 1 January 2022. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

Trajno se odbijaju osobe koje su zbog svog ponašanja ili aktivnosti izložene riziku dobivanja zaraznih bolesti koje se mogu prenijeti krvlju: [...] muškarci koji su u životu imali spolne odnose s drugim muškarcima, [...]

- ^ Orhidea Gaura (29 June 2012). "Biti gay u Hrvatskoj vojsci" [Being gay in the Croatian military] (in Croatian). Arhiva.nacional.hr. Retrieved 25 May 2016.

- ^ "Hrvatska vojska: Gay je OK – Večernji.hr". Vecernji.hr. Retrieved 25 May 2016.

- ^ Refugees, United Nations High Commissioner for. "Refworld – Croatia: Homosexuality: its legal status and the public attitude towards it; whether homosexuals can complain about discrimination and, if so, to whom (January 1998 – May 1999)".

- ^ "Biti gay u Hrvatskoj vojsci – Nacional.hr". arhiva.nacional.hr.

- ^ "V Splitu brutalno pretepli prostovoljca iz skupine Split Pride". www.24ur.com (in Slovenian). Retrieved 5 November 2021.

- ^ Michael Lipka (12 December 2013). "Eastern and Western Europe divided over gay marriage, homosexuality". Pew Research Center. Retrieved 2 July 2015.

- ^ "SEEbiz.eu / Anketa: 53,5% građana ne podupire gay parade".

- ^ "55,3 posto Hrvata za brak žene i muškarca u Ustavu!" (in Croatian). Vecernji.hr. Retrieved 19 August 2013.

- ^ "Anketa za HRT: 59 posto građana ZA promjenu Ustava > Slobodna Dalmacija > Hrvatska". 15 March 2014. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- ^ admin2. "Matičari u Zagrebu bez priziva savjesti – CroL". Archived from the original on 29 July 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ admin2. "'Isprva bi nam bilo čudno, ali organizirali bismo vjenčanja istospolnih parova' – CroL". Archived from the original on 20 July 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Pilarov Barometar Hrvatskog Društva – Same-sex marriages". Institut društvenih znanosti Ivo Pilar. June 2014. Retrieved 14 August 2014.

- ^ "Predsjednik treba biti... poliglot, skroman i solidaran s narodom, protiv operacija HV-a u NATO-u". Večernji.hr.

- ^ "Eurobarometer Discrimination in the EU in 2015 – Croatia Factsheet". European Commission. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ^ "Istraživanje: bi li građani Hrvatske prihvatili gej susjede i odobrili kriminalizaciju LGBT osoba ? – CroL". Crol.hr. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- ^ "Religious Belief and National Belonging in Central and Eastern Europe". Pew Research Center. 10 May 2017. Retrieved 11 May 2017.

- ^ "Final Topline" (PDF). Pew. Retrieved 15 May 2017.

- ^ "Discrimination in the EU_sp535_volumeA.xlsx [QB15_2] and [QB15_3]" (xls). data.europa.eu. 22 December 2023. Retrieved 29 December 2023.

- ^ "About". Queer Zagreb. Archived from the original on 2 April 2013. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- ^ tamara3. "Predstavljen LGBTIQ+ centar Druga Rijeka – CroL". Archived from the original on 18 October 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Split dobio LGBT Centar, sve spremno za Povorku ponosa – CroL". Archived from the original on 26 May 2014.

- ^ "Otvorenje LGBT centra". Gay.hr. 3 May 2013. Archived from the original on 2 November 2014. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- ^ "Zagreb sa 37 friendly lokacija postaje prava gay destinacija". Jutarnji.hr. 26 April 2010. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- ^ "Gay Croatia". GayTimes. 30 June 2011. Archived from the original on 4 September 2013. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- ^ "The island of Rab – Gay-friendly | Gay Croatia". Friendlycroatia.com. Archived from the original on 23 September 2013. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- ^ "Gay Dubrovnik | Gay Croatia". Friendlycroatia.com. Archived from the original on 6 January 2014. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- ^ Maya Jaggi (10 July 2015). "In the eye of austerity: the Thessaloniki Biennale". FT.com. Archived from the original on 11 December 2022. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- ^ "Povorka ponosa". Zagreb-pride.net. Archived from the original on 14 October 2013. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- ^ "Događaj visokog rizika: Danas je jubilarni Zagreb Pride". 24sata.info. Archived from the original on 14 January 2019. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- ^ "Zbogom Queer, očekujemo Pride". Novossti.com. 26 May 2012. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- ^ "15.000 ljudi u dvanaestoj Povorci ponosa! (foto, video) – CroL". CroL.hr. Archived from the original on 15 July 2013. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- ^ Ivica, Profaca (11 June 2011). "VIDEO: Splitski kordon mržnje" [VIDEO: Split Cordon of Hate]. Danas (in Croatian). Archived from the original on 6 April 2012. Retrieved 31 May 2012.

- ^ "Say 'NO' to violence, join Zagreb Pride!". Index.hr (in Croatian). 17 June 2011. Retrieved 31 May 2012.

- ^ "U Rijeci održan marš podrške!". Queer.hr. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- ^ "Drugi Split Pride je uspio – može se kad se hoće". tportal.hr. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- ^ "Više od 300 Riječana marširalo u znak podrške Split Prideu". tportal.hr. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- ^ "LORI - O Lori". Archived from the original on 14 June 2012. Retrieved 11 June 2012.

- ^ "Lesbian group Kontra". Kontra.hr. Archived from the original on 5 December 2013. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- ^ "'Da je ovako bilo '91. rat bi trajao 6 sati, a ne 6 godina'". Dnevnik.hr. 9 June 2012. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- ^ "Uhićene 73 osobe, protiv 60 podnijete prekršajne prijave". tportal.hr. 6 October 2012. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- ^ "mobile.net.hr". Danas.net.hr. 8 June 2013. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- ^ Vlado Kos / Cropix / copyrighted (6 September 2014). "POLOŽEN ISPIT TOLERANCIJE Bez ijednog ružnog povika održan prvi Osijek Pride -Jutarnji List". Jutarnji.hr. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- ^ "U gradu na četiri rijeke održana prva povorka ponosa, Pride i u Splitu: "Mi imamo europske zakone, ali ne usađujemo ljudima europske vrijednosti"" [The first Pride parade held in the city on four rivers: "We have European laws, but we don't instill European values in people."]. dnevnik.hr. Nova TV. 3 June 2023. Archived from the original on 1 December 2023. Retrieved 30 June 2024.

- ^ a b Anđelković, Kristina (5 June 2023). "Karlovac Pride parade held for 1st time". total-croatia-news.com. Total Croatia. Archived from the original on 21 February 2024. Retrieved 30 June 2024.

- ^ Anđelković, Kristina (20 May 2024). "Drugi karlovački Pride početkom lipnja, ove godine prvi puta ikada i šarena povorka u centru grada" [The second Karlovac Pride at the beginning of June, this year for the first time ever a colorful parade in the city center]. radio-mreznica.hr. Radio Mrežnica. Archived from the original on 30 June 2024. Retrieved 30 June 2024.

- ^ Čelebija, Matea (17 February 2024). "Pride će se prvi put održati u Puli. Pitali smo ljude što misle o tome, pogledajte" [Pride will be held in Pula for the first time. We asked people what they thought about it, check it out]. index.hr. Index.hr. Archived from the original on 24 February 2024. Retrieved 30 June 2024.

- ^ "UŽIVO Pula Pride: 500-tinjak ljudi prošlo Pulom u prvoj Paradi ponosa (foto i video)" [LIVE Pula Pride: about 500 people marched through Pula in the first Pride Parade (photo and video)]. istarski.hr. Iskarski.hr. 22 June 2024. Archived from the original on 30 June 2024. Retrieved 30 June 2024.

- ^ Samardžić, Renato (23 June 2024). "'Ćakule ne delaju fritule': evo kako je prošao prvi Pula-Pola Pride". crol.hr. Crol. Archived from the original on 24 June 2024. Retrieved 30 June 2024.

- ^ "Zagreb na Markovom trgu odlučno zatražio bračnu jednakost (foto, video)". CroL.hr. 27 May 2013. Archived from the original on 8 July 2013. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- ^ "Zagreb, Rijeka, Split i Pula glasno poručili 'protiv' (foto)". Crol.hr. 30 November 2013. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 23 January 2014.

- ^ "U Zagrebu održan prvi Balkanski Trans Inter Marš: Nećete nas brisati! - CroL". www.crol.hr. Retrieved 3 July 2019.

- ^ "Gay.hr". Gay.hr. Archived from the original on 2 January 2014. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- ^ Krešimir Žabec (31 December 2013). "Veleposlanik Finske predao vjerodajanice u pratnji svoga muža". Jutarnji.hr. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 23 January 2014.

- ^ "Josipovic expresses support for gay pride parade in Split". Croatian Times. 3 March 2011. Archived from the original on 16 March 2012. Retrieved 31 May 2012.

- ^ "Holy predstavila novu stranku: Orah će biti treća politička opcija". Večernji.hr.

- ^ "Ponosim se svojim LGBT aktivizmom – Politika". H-Alter. Archived from the original on 6 August 2014. Retrieved 17 August 2013.