Seneca the Younger

Seneca the Younger | |

|---|---|

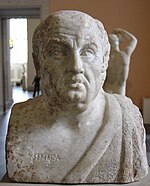

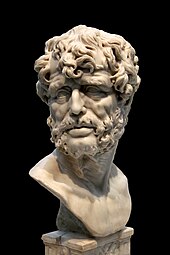

Ancient bust of Seneca, part of the Double Herm of Socrates and Seneca | |

| Born | c. 4 BC |

| Died | AD 65 (aged 68–69) Rome, Roman Italy, Roman Empire |

| Nationality | Roman |

| Other names | Seneca the Younger, Seneca |

| Notable work | Epistulae Morales ad Lucilium Medea Thyestes Phaedra |

| Parent | Seneca the Elder (father) |

| Era | Hellenistic philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Stoicism |

Main interests | Ethics |

Notable ideas | Problem of evil |

Lucius Annaeus Seneca the Younger (/ˈsɛnɪkə/ SEN-ik-ə; c. 4 BC – AD 65),[1] usually known mononymously as Seneca, was a Stoic philosopher of Ancient Rome, a statesman, dramatist, and in one work, satirist, from the post-Augustan age of Latin literature.

Seneca was born in Colonia Patricia Corduba in Hispania, and was trained in rhetoric and philosophy in Rome. His father was Seneca the Elder, his elder brother was Lucius Junius Gallio Annaeanus, and his nephew was the poet Lucan. In AD 41, Seneca was exiled to the island of Corsica under emperor Claudius,[2] but was allowed to return in 49 to become a tutor to Nero. When Nero became emperor in 54, Seneca became his advisor and, together with the praetorian prefect Sextus Afranius Burrus, provided competent government for the first five years of Nero's reign. Seneca's influence over Nero declined with time, and in 65 Seneca was forced to take his own life for alleged complicity in the Pisonian conspiracy to assassinate Nero, of which he was probably innocent.[3] His stoic and calm suicide has become the subject of numerous paintings.

As a writer, Seneca is known for his philosophical works, and for his plays, which are all tragedies. His prose works include 12 essays and 124 letters dealing with moral issues. These writings constitute one of the most important bodies of primary material for ancient Stoicism. As a tragedian, he is best known for plays such as his Medea, Thyestes, and Phaedra. Seneca had an immense influence on later generations—during the Renaissance he was "a sage admired and venerated as an oracle of moral, even of Christian edification; a master of literary style and a model [for] dramatic art."[4]

Life[edit]

Early life, family and adulthood[edit]

Seneca was born in Córdoba in the Roman province of Baetica in Hispania.[5] His branch of the Annaea gens consisted of Italic colonists, of Umbrian or Paelignian origins.[6] His father was Lucius Annaeus Seneca the Elder, a Spanish-born Roman knight who had gained fame as a writer and teacher of rhetoric in Rome.[7] Seneca's mother, Helvia, was from a prominent Baetician family.[8] Seneca was the second of three brothers; the others were Lucius Annaeus Novatus (later known as Junius Gallio), and Annaeus Mela, the father of the poet Lucan.[9] Miriam Griffin says in her biography of Seneca that "the evidence for Seneca's life before his exile in 41 is so slight, and the potential interest of these years, for social history, as well as for biography, is so great that few writers on Seneca have resisted the temptation to eke out knowledge with imagination."[10] Griffin also infers from the ancient sources that Seneca was born in either 8, 4, or 1 BC. She thinks he was born between 4 and 1 BC and was resident in Rome by AD 5.[10]

Seneca is said to have been taken to Rome in the "arms" of his aunt (his mother's stepsister) at a young age, probably when he was about five years old.[11] His father resided for much of his life in the city.[12] Seneca was taught the usual subjects of literature, grammar, and rhetoric, as part of the standard education of high-born Romans.[13] While still young he received philosophical training from Attalus the Stoic, and from Sotion and Papirius Fabianus, both of whom belonged to the short-lived School of the Sextii, which combined Stoicism with Pythagoreanism.[9] Sotion persuaded Seneca when he was a young man (in his early twenties) to become a vegetarian, which he practiced for around a year before his father urged him to desist because the practice was associated with "some foreign rites".[14] Seneca often had breathing difficulties throughout his life, probably asthma,[15] and at some point in his mid-twenties (c. AD 20) he appears to have been struck down with tuberculosis.[16] He was sent to Egypt to live with his aunt (the same aunt who had brought him to Rome), whose husband Gaius Galerius had become Prefect of Egypt.[8] She nursed him through a period of ill health that lasted up to ten years.[17] In 31 AD he returned to Rome with his aunt, his uncle dying en route in a shipwreck.[17] His aunt's influence helped Seneca be elected quaestor (probably after AD 37[13]), which also earned him the right to sit in the Roman Senate.[17]

Politics and exile[edit]

Seneca's early career as a senator seems to have been successful and he was praised for his oratory.[18] In his writings Seneca has nothing good to say about Caligula and frequently depicts him as a monster.[19] Cassius Dio relates a story that Caligula was so offended by Seneca's oratorical success in the Senate that he ordered him to commit suicide.[18] Seneca survived only because he was seriously ill and Caligula was told that he would soon die anyway.[18] Seneca explains his own survival as due to his patience and his devotion to his friends: "I wanted to avoid the impression that all I could do for loyalty was die."[20]

In AD 41, Claudius became emperor, and Seneca was accused by the new empress Messalina of adultery with Julia Livilla, sister to Caligula and Agrippina.[21] The affair has been doubted by some historians, since Messalina had clear political motives for getting rid of Julia Livilla and her supporters.[12][22] The Senate pronounced a death sentence on Seneca, which Claudius commuted to exile, and Seneca spent the next eight years on the island of Corsica.[23] Two of Seneca's earliest surviving works date from the period of his exile—both consolations.[21] In his Consolation to Helvia, his mother, Seneca comforts her as a bereaved mother for losing her son to exile.[23] Seneca incidentally mentions the death of his only son, a few weeks before his exile.[23] Later in life Seneca was married to a woman younger than himself, Pompeia Paulina.[9] It has been thought that the infant son may have been from an earlier marriage,[23] but the evidence is "tenuous".[9] Seneca's other work of this period, his Consolation to Polybius, one of Claudius' freedmen, focused on consoling Polybius on the death of his brother. It is noted for its flattery of Claudius, and Seneca expresses his hope that the emperor will recall him from exile.[23] In 49 AD Agrippina married her uncle Claudius, and through her influence Seneca was recalled to Rome.[21] Agrippina gained the praetorship for Seneca and appointed him tutor to her son, the future emperor Nero.[24]

Imperial advisor[edit]

From AD 54 to 62, Seneca acted as Nero's advisor, together with the praetorian prefect Sextus Afranius Burrus. Early in Nero's reign, his mother Agrippina exercised his authority to make decisions. Seneca and Burrus opposed this authoritarian matriarchy which had become the cause of irresponsibility of the emperor. One by-product of his new position was that Seneca was appointed suffect consul in 56.[25] Seneca's influence was said to have been especially strong in the first year.[26] Seneca composed Nero's accession speeches in which he promised to restore proper legal procedure and authority to the Senate.[24] He also composed the eulogy for Claudius that Nero delivered at the funeral.[24] Seneca's satirical skit Apocolocyntosis, which lampoons the deification of Claudius and praises Nero, dates from the earliest period of Nero's reign.[24] In AD 55, Seneca wrote On Clemency following Nero's murder of Britannicus, perhaps to assure the citizenry that the murder was the end, not the beginning of bloodshed.[27] On Clemency is a work which, although it flatters Nero, was intended to show the correct (Stoic) path of virtue for a ruler.[24] Tacitus and Dio suggest that Nero's early rule, during which he listened to Seneca and Burrus, was quite competent. However, the ancient sources suggest that, over time, Seneca and Burrus lost their influence over the emperor. In 59 they had reluctantly agreed to Agrippina's murder, and afterward Tacitus reports that Seneca had to write a letter justifying the murder to the Senate.[27]

In AD 58 the senator Publius Suillius Rufus made a series of public attacks on Seneca.[28] These attacks, reported by Tacitus and Cassius Dio,[29] included charges that, in a mere four years of service to Nero, Seneca had acquired a vast personal fortune of three hundred million sestertii by charging high interest on loans throughout Italy and the provinces.[30] Suillius' attacks included claims of sexual corruption, with a suggestion that Seneca had slept with Agrippina.[31] Tacitus, though, reports that Suillius was highly prejudiced: he had been a favorite of Claudius,[28] and had been an embezzler and informant.[30] In response, Seneca brought a series of prosecutions for corruption against Suillius: half of his estate was confiscated and he was sent into exile.[32] However, the attacks reflect a criticism of Seneca that was made at the time and continued through later ages.[28] Seneca was undoubtedly extremely rich: he had properties at Baiae and Nomentum, an Alban villa, and Egyptian estates.[28] Cassius Dio even reports that the Boudica uprising in Britannia was caused by Seneca forcing large loans on the indigenous British aristocracy in the aftermath of Claudius's conquest of Britain, and then calling them in suddenly and aggressively.[28] Seneca was sensitive to such accusations: his De Vita Beata ("On the Happy Life") dates from around this time and includes a defense of wealth along Stoic lines, arguing that properly gaining and spending wealth is appropriate behavior for a philosopher.[30]

Retirement[edit]

After Burrus's death in 62, Seneca's influence declined rapidly; as Tacitus puts it (Ann. 14.52.1), mors Burri infregit Senecae potentiam ("the death of Burrus broke Seneca's power").[33] Tacitus reports that Seneca tried to retire twice, in 62 and AD 64, but Nero refused him on both occasions.[30] Nevertheless, Seneca was increasingly absent from the court.[30] He adopted a quiet lifestyle on his country estates, concentrating on his studies and seldom visiting Rome. It was during these final few years that he composed two of his greatest works: Naturales quaestiones—an encyclopedia of the natural world; and his Letters to Lucilius—which document his philosophical thoughts.[34]

Death[edit]

In AD 65, Seneca was caught up in the aftermath of the Pisonian conspiracy, a plot to kill Nero. Although it is unlikely that Seneca was part of the conspiracy, Nero ordered him to kill himself.[30] Seneca followed tradition by severing several veins in order to bleed to death, and his wife Pompeia Paulina attempted to share his fate. Cassius Dio, who wished to emphasize the relentlessness of Nero, focused on how Seneca had attended to his last-minute letters, and how his death was hastened by soldiers.[35] A generation after the Julio-Claudian emperors, Tacitus wrote an account of the suicide, which, in view of his Republican sympathies, is perhaps somewhat romanticized.[36] According to this account, Nero ordered Seneca's wife saved. Her wounds were bound up and she made no further attempt to kill herself. As for Seneca himself, his age and diet were blamed for slow loss of blood and extended pain rather than a quick death. He also took poison, which was not fatal.

After dictating his last words to a scribe, and with a circle of friends attending him in his home, he immersed himself in a warm bath, which he expected would speed blood flow and ease his pain. Tacitus wrote, "He was then carried into a bath, with the steam of which he was suffocated, and he was burnt without any of the usual funeral rites. So he had directed in a codicil of his will, even when in the height of his wealth and power he was thinking of life's close."[36] This may give the impression of a favorable portrait of Seneca, but Tacitus's treatment of him is at best ambivalent. Alongside Seneca's apparent fortitude in the face of death, for example, one can also view his actions as rather histrionic and performative; and when Tacitus tells us that he left his family an imago suae vitae (Annales 15.62), "an image of his life", he is possibly being ambiguous: in Roman culture, the imago was a kind of mask that commemorated the great ancestors of noble families, but at the same time, it may also suggest duplicity, superficiality, and pretense.[37]

Philosophy[edit]

As "a major philosophical figure of the Roman Imperial Period",[38] Seneca's lasting contribution to philosophy has been to the school of Stoicism. His writing is highly accessible[39][40] and was the subject of attention from the Renaissance onwards by writers such as Michel de Montaigne.[41] He has been described as “a towering and controversial figure of antiquity”[42] and “the world’s most interesting Stoic”.[43]

Seneca wrote a number of books on Stoicism, mostly on ethics, with one work (Naturales Quaestiones) on the physical world.[44] Seneca built on the writings of many of the earlier Stoics: he often mentions Zeno, Cleanthes, and Chrysippus;[45] and frequently cites Posidonius, with whom Seneca shared an interest in natural phenomena.[46] He frequently quotes Epicurus, especially in his Letters.[47] His interest in Epicurus is mainly limited to using him as a source of ethical maxims.[48] Likewise Seneca shows some interest in Platonist metaphysics, but never with any clear commitment.[49] His moral essays are based on Stoic doctrines.[40] Stoicism was a popular philosophy in this period, and many upper-class Romans found in it a guiding ethical framework for political involvement.[44] It was once popular to regard Seneca as being very eclectic in his Stoicism,[50] but modern scholarship views him as a fairly orthodox Stoic, albeit a free-minded one.[51]

His works discuss both ethical theory and practical advice, and Seneca stresses that both parts are distinct but interdependent.[52] His Letters to Lucilius showcase Seneca's search for ethical perfection[52] and “represent a sort of philosophical testament for posterity”.[42] Seneca regards philosophy as a balm for the wounds of life.[53] The destructive passions, especially anger and grief, must be uprooted,[54] or moderated according to reason.[55] He discusses the relative merits of the contemplative life and the active life,[53] and he considers it important to confront one's own mortality and be able to face death.[54][55] One must be willing to practice poverty and use wealth properly,[56] and he writes about favours, clemency, the importance of friendship, and the need to benefit others.[56][53][57] The universe is governed for the best by a rational providence,[56] and this must be reconciled with acceptance of adversity.[54]

Drama[edit]

Ten plays are attributed to Seneca, of which most likely eight were written by him.[58] The plays stand in stark contrast to his philosophical works. With their intense emotions, and grim overall tone, the plays seem to represent the antithesis of Seneca's Stoic beliefs.[59] Up to the 16th century it was normal to distinguish between Seneca the moral philosopher and Seneca the dramatist as two separate people.[60] Scholars have tried to spot certain Stoic themes: it is the uncontrolled passions that generate madness, ruination, and self-destruction.[61] This has a cosmic as well as an ethical aspect, and fate is a powerful, albeit rather oppressive, force.[61]

Many scholars have thought, following the ideas of the 19th-century German scholar Friedrich Leo, that Seneca's tragedies were written for recitation only.[62] Other scholars think that they were written for performance and that it is possible that actual performance took place in Seneca's lifetime.[63] Ultimately, this issue cannot be resolved on the basis of our existing knowledge.[58] The tragedies of Seneca have been successfully staged in modern times.

The dating of the tragedies is highly problematic in the absence of any ancient references.[64] A parody of a lament from Hercules Furens appears in the Apocolocyntosis, which implies a date before AD 54 for that play.[64] A relative chronology has been proposed on metrical grounds.[65] The plays are not all based on the Greek pattern; they have a five-act form and differ in many respects from extant Attic drama, and while the influence of Euripides on some of these works is considerable, so is the influence of Virgil and Ovid.[64]

Seneca's plays were widely read in medieval and Renaissance European universities and strongly influenced tragic drama in that time, such as Elizabethan England (William Shakespeare and other playwrights), France (Corneille and Racine), and the Netherlands (Joost van den Vondel).[66] English translations of Seneca's tragedies appeared in print in the mid-16th century, with all ten published collectively in 1581.[67] He is regarded as the source and inspiration for what is known as "Revenge Tragedy", starting with Thomas Kyd's The Spanish Tragedy and continuing well into the Jacobean era.[68] Thyestes is considered Seneca's masterpiece,[69] and has been described by scholar Dana Gioia as "one of the most influential plays ever written".[70] Medea is also highly regarded,[71][72] and was praised along with Phaedra by T. S. Eliot.[70]

Works[edit]

Works attributed to Seneca include 12 philosophical essays, 124 letters dealing with moral issues, nine tragedies, and a satire, the attribution of which is disputed.[73] His authorship of Hercules on Oeta has also been questioned.

Seneca's tragedies[edit]

Fabulae crepidatae (tragedies with Greek subjects):

- Hercules or Hercules furens (The Madness of Hercules)

- Troades (The Trojan Women)

- Phoenissae (The Phoenician Women)

- Medea

- Phaedra

- Oedipus

- Agamemnon

- Thyestes

- Hercules Oetaeus (Hercules on Oeta): generally considered not written by Seneca. First rejected by Daniël Heinsius.

Fabula praetexta (tragedy in Roman setting):

- Octavia: almost certainly not written by Seneca (at least in its final form) since it contains accurate prophecies of both his and Nero's deaths.[74] This play closely resembles Seneca's plays in style, but was probably written some time after Seneca's death (perhaps under Vespasian) by someone influenced by Seneca and aware of the events of his lifetime.[75] Though attributed textually to Seneca, the attribution was early questioned by Petrarch,[76] and rejected by Justus Lipsius.

Essays and letters[edit]

Essays[edit]

Traditionally given in the following order:

- (64) De Providentia (On providence) – addressed to Lucilius

- (55) De Constantia Sapientis (On the Firmness of the Wise Person) – addressed to Serenus

- (41) De Ira (On anger) – A study on the consequences and the control of anger – addressed to his brother Novatus

- (book 2 of the De Ira)

- (book 3 of the De Ira)

- (40) Ad Marciam, De consolatione (To Marcia, On Consolation) – Consoles her on the death of her son

- (58) De Vita Beata (On the Happy Life) – addressed to Gallio

- (62) De Otio (On Leisure) – addressed to Serenus

- (63) De Tranquillitate Animi (On the tranquillity of mind) – addressed to Serenus

- (49) De Brevitate Vitæ (On the shortness of life) – Essay expounding that any length of life is sufficient if lived wisely – addressed to Paulinus

- (44) De Consolatione ad Polybium (To Polybius, On consolation) – Consoling him on the death of his brother.

- (42) Ad Helviam matrem, De consolatione (To mother Helvia, On consolation) – Letter to his mother consoling her on his absence during exile.

Other essays[edit]

- (56) De Clementia (On Clemency) – written to Nero on the need for clemency as a virtue in an emperor.[77]

- (63) De Beneficiis (On Benefits) [seven books]

- (–) De Superstitione (On Superstition) – lost, but quoted from in Saint Augustine's City of God 6.10–6.11.

Letters[edit]

- (64) Epistulae Morales ad Lucilium – collection of 124 letters, sometimes divided into 20 books, dealing with moral issues written to Lucilius Junior. This work has possibly come down to us incomplete; the miscellanist Aulus Gellius refers, in his Noctes Atticae (12.2), to a 'book 22'.

Other[edit]

- (54) Apocolocyntosis divi Claudii (The Gourdification of the Divine Claudius), a satirical work.

- (63) Naturales quaestiones [seven books] an insight into ancient theories of cosmology, meteorology, and similar subjects.

Spurious[edit]

- (58–62/370?) Cujus etiam ad Paulum apostolum leguntur epistolae: These letters, allegedly between Seneca and St Paul, were revered by early authorities, but modern scholarship rejects their authenticity.[78][79]

Editions[edit]

- Naturales quaestiones (in Latin). Venezia: eredi Aldo Manuzio (1.) & Andrea Torresano (1.). 1522.

Legacy[edit]

As a proto-Christian saint[edit]

Seneca's writings were well known in the later Roman period, and Quintilian, writing thirty years after Seneca's death, remarked on the popularity of his works amongst the youth.[80] While he found much to admire, Quintillian criticized Seneca for what he regarded as a degenerate literary style—a criticism echoed by Aulus Gellius in the middle of the 2nd century.[80]

The early Christian Church was very favourably disposed towards Seneca and his writings, and the church leader Tertullian possessively referred to him as "our Seneca".[81] By the 4th century an apocryphal correspondence with Paul the Apostle had been created linking Seneca into the Christian tradition.[82] The letters are mentioned by Jerome who also included Seneca among a list of Christian writers, and Seneca is similarly mentioned by Augustine.[82] In the 6th century Martin of Braga synthesized Seneca's thought into a couple of treatises that became popular in their own right.[83] Otherwise, Seneca was mainly known through a large number of quotes and extracts in the florilegia, which were popular throughout the medieval period.[83] When his writings were read in the later Middle Ages, it was mostly his Letters to Lucilius—the longer essays and plays being relatively unknown.[84]

Medieval writers and works continued to link him to Christianity because of his alleged association with Paul.[85] The Golden Legend, a 13th-century hagiographical account of famous saints that was widely read, included an account of Seneca's death scene, and erroneously presented Nero as a witness to Seneca's suicide.[85] Dante placed Seneca (alongside Cicero) among the "great spirits" in the First Circle of Hell, or Limbo.[86] Boccaccio, who in 1370 came across the works of Tacitus whilst browsing the library at Montecassino, wrote an account of Seneca's suicide hinting that it was a kind of disguised baptism, or a de facto baptism in spirit.[87] Some, such as Albertino Mussato and Giovanni Colonna, went even further and concluded that Seneca must have been a Christian convert.[88]

Disputed quotations[edit]

Various other antique and medieval texts purport to be by Seneca, e.g., De remediis fortuitorum, but with unconfirmed authorship, they have sometimes been referred-to as "Pseudo-Seneca".[89] At least some of these seem to preserve and adapt genuine Senecan content, for example, Saint Martin of Braga's (d. c. 580) Formula vitae honestae, or De differentiis quatuor virtutum vitae honestae ("Rules for an Honest Life", or "On the Four Cardinal Virtues"). Early manuscripts preserve Martin's preface, where he makes it clear that this was his adaptation, but in later copies this was omitted, and the work was later thought fully Seneca's work.[90] Seneca is also often quoted as the author of the aphorism: "Religion is regarded by the common people as true, by the wise as false, and by the rulers as useful".[91] However, this quote is similar to a statement by Edward Gibbon: "The various modes of worship which prevailed in the Roman world were all considered by the people as equally true; by the philosophers as equally false; and by the magistrate as equally useful.", so it is disputed.

An improving reputation[edit]

Seneca remains one of the few popular Roman philosophers from the period. He appears not only in Dante, but also in Chaucer and to a large degree in Petrarch, who adopted his style in his own essays and who quotes him more than any other authority except Virgil. In the Renaissance, printed editions and translations of his works became common, including an edition by Erasmus and a commentary by John Calvin.[92] John of Salisbury, Erasmus and others celebrated his works. French essayist Montaigne, who gave a spirited defense of Seneca and Plutarch in his Essays, was himself considered by Pasquier a "French Seneca".[93] Similarly, Thomas Fuller praised Joseph Hall as "our English Seneca". Many who considered his ideas not particularly original still argued that he was important in making the Greek philosophers presentable and intelligible.[94] His suicide has also been a popular subject in art, from Jacques-Louis David's 1773 painting The Death of Seneca to the 1951 film Quo Vadis.

Even with the admiration of an earlier group of intellectual stalwarts, Seneca has never been without his detractors. In his own time, he was accused of hypocrisy or, at least, a less than "Stoic" lifestyle. While banished to Corsica, he wrote a plea for restoration rather incompatible with his advocacy of a simple life and the acceptance of fate. In his Apocolocyntosis he ridiculed the behaviors and policies of Claudius, and flattered Nero—such as proclaiming that Nero would live longer and be wiser than the legendary Nestor. The claims of Publius Suillius Rufus that Seneca acquired some "three hundred million sesterces" through Nero's favor are highly partisan, but they reflect the reality that Seneca was both powerful and wealthy.[95] Robin Campbell, a translator of Seneca's letters, writes that the "stock criticism of Seneca right down the centuries [has been]...the apparent contrast between his philosophical teachings and his practice."[95]

In 1562 Gerolamo Cardano wrote an apology praising Nero in his Encomium Neronis, printed in Basel.[96] This was likely intended as a mock encomium, inverting the portrayal of Nero and Seneca that appears in Tacitus.[97] In this work Cardano portrayed Seneca as a crook of the worst kind, an empty rhetorician who was only thinking to grab money and power, after having poisoned the mind of the young emperor. Cardano stated that Seneca well deserved death.

Among the historians who have sought to reappraise Seneca is the scholar Anna Lydia Motto, who in 1966 argued that the negative image has been based almost entirely on Suillius's account, while many others who might have lauded him have been lost.[98]

"We are therefore left with no contemporary record of Seneca's life, save for the desperate opinion of Publius Suillius. Think of the barren image we should have of Socrates, had the works of Plato and Xenophon not come down to us and were we wholly dependent upon Aristophanes' description of this Athenian philosopher. To be sure, we should have a highly distorted, misconstrued view. Such is the view left to us of Seneca, if we were to rely upon Suillius alone."[99]

More recent work is changing the dominant perception of Seneca as a mere conduit for pre-existing ideas, showing originality in Seneca's contribution to the history of ideas. Examination of Seneca's life and thought in relation to contemporary education and to the psychology of emotions is revealing the relevance of his thought. For example, Martha Nussbaum in her discussion of desire and emotion includes Seneca among the Stoics who offered important insights and perspectives on emotions and their role in our lives.[100] Specifically devoting a chapter to his treatment of anger and its management, she shows Seneca's appreciation of the damaging role of uncontrolled anger, and its pathological connections. Nussbaum later extended her examination to Seneca's contribution to political philosophy[101] showing considerable subtlety and richness in his thoughts about politics, education, and notions of global citizenship—and finding a basis for reform-minded education in Seneca's ideas she used to propose a mode of modern education that avoids both narrow traditionalism and total rejection of tradition. Elsewhere Seneca has been noted as the first great Western thinker on the complex nature and role of gratitude in human relationships.[102]

In popular culture[edit]

- The movie Seneca was released in 2023, narrating his life[103]

Notable fictional portrayals[edit]

Seneca is a character in Monteverdi's 1642 opera L'incoronazione di Poppea (The Coronation of Poppea), which is based on the pseudo-Senecan play, Octavia.[104]

- In Nathaniel Lee's 1675 play Nero, Emperor of Rome, Seneca attempts to dissuade Nero from his egomaniacal plans, but is dragged off to prison, dying off-stage.[105]

- Seneca appears in Robert Bridges' verse drama Nero, the second part of which (published 1894) culminates in Seneca's death.[106]

- Seneca also appears in a fairly minor role in Henryk Sienkiewicz's 1896 novel Quo Vadis and was played by Nicholas Hannen in the 1951 film.[107]

- In Robert Graves's 1934 book Claudius the God, the sequel novel to I, Claudius, Seneca is portrayed as an unbearable sycophant.[108] He is shown as a flatterer who converts to Stoicism solely to appease Claudius's own ideology. The "Pumpkinification" (Apocolocyntosis) to Graves thus becomes an unbearable work of flattery to the loathsome Nero, mocking a man that Seneca groveled to for years.

- The historical novel Chariot of the Soul by Linda Proud features Seneca as tutor of the young Togidubnus, son of King Verica of the Atrebates, during his ten-year stay in Rome.[109]

- The 2023 film Seneca – On the Creation of Earthquakes focuses on the final days of Seneca, portrayed by John Malkovich.[110][111]

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica, s.v. Seneca.

- ^ Fitch, John (2008). Seneca. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-0199282081.

- ^ Bunson, Matthew (1991). A Dictionary of the Roman Empire. Oxford University Press. p. 382.

- ^ Watling, E. F. (1966). "Introduction". Four Tragedies and Octavia. Penguin Books. p. 9.

- ^ Habinek 2013, p. 6

- ^ George Davis Chase, "The Origin of Roman Praenomina", in Harvard Studies in Classical Philology, vol. VIII, pp. 103–184 (1897).

- ^ Dando-Collins, Stephen (2008). Blood of the Caesars: How the Murder of Germanicus Led to the Fall of Rome. John Wiley & Sons. p. 47. ISBN 978-0470137413.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Habinek 2013, p. 7

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Reynolds, Griffin & Fantham 2012, p. 92

- ^ Jump up to: a b Miriam T. Griffin. Seneca: A Philosopher in Politics, Oxford 1976. 34.

- ^ Wilson 2014, p. 48 citing De Consolatione ad Helviam Matrem 19.2

- ^ Jump up to: a b Asmis, Bartsch & Nussbaum 2012, p. vii

- ^ Jump up to: a b Habinek 2013, p. 8

- ^ Wilson 2014, p. 56

- ^ Wilson 2014, p. 32

- ^ Wilson 2014, p. 57

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Wilson 2014, p. 62

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Braund 2015, p. 24

- ^ Wilson 2014, p. 67

- ^ Wilson 2014, p. 67 citing Naturales Quaestiones, 4.17

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Habinek 2013, p. 9

- ^ Wilson 2014, p. 79

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Braund 2015, p. 23

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Braund 2015, p. 22

- ^ The Senatus Consultum Trebellianum was dated to 25 August in his consulate, which he shared with Trebellius Maximus. Digest 36.1.1

- ^ Cassius Dio claims Seneca and Burrus "took the rule entirely into their own hands," but "after the death of Britannicus, Seneca and Burrus no longer gave any careful attention to the public business" in 55 (Cassius Dio, Roman History, LXI. 3–7)

- ^ Jump up to: a b Habinek 2013, p. 10

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Braund 2015, p. 21

- ^ Tacitus, Annals xiii.42; Cassius Dio, Roman History lxi.33.9.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Asmis, Bartsch & Nussbaum 2012, p. ix

- ^ Wilson 2014, p. 130

- ^ Wilson 2014, p. 131

- ^ Braund 2015, p. viii

- ^ Habinek 2013, p. 14

- ^ Habinek 2013, p. 16 citing Cassius Dio ii.25

- ^ Jump up to: a b Church, Alfred John; Brodribb, William Jackson (2007). "xv". Tacitus: The Annals of Imperial Rome. New York: Barnes & Noble. p. 341. citing Tacitus Annals, xv. 60–64

- ^ Cf. especially Beard, M., "How Stoical was Seneca?", in the New York Review of Books, Oct. 9, 2014.

- ^ Vogt, Katja (2016), "Seneca", in Zalta, Edward N. (ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2016 ed.), Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, retrieved 19 August 2019

- ^ Gill 1999, pp. 49–50

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gill 1999, p. 37

- ^ Seneca, Lucius Annaeus (1968). Stoic Philosophy of Seneca. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0393004597.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Massimo Pigliucci on Seneca's Stoic philosophy of happiness – Massimo Pigliucci | Aeon Classics". Aeon. Retrieved 19 August 2019.

- ^ "Who Is Seneca? Inside The Mind of The World's Most Interesting Stoic". Daily Stoic. 10 July 2016. Retrieved 19 August 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gill 1999, p. 34

- ^ Sellars 2013, p. 103

- ^ Sellars 2013, p. 105

- ^ Sellars 2013, p. 106

- ^ Sellars 2013, p. 107

- ^ Sellars 2013, p. 108

- ^ "His philosophy, so far as he adopted a system, was the stoical, but it was rather an eclecticism of stoicism than pure stoicism"

Long, George (1870). "Seneca, L. Annaeus". In Smith, William (ed.). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology. Vol. 3. p. 782.

Long, George (1870). "Seneca, L. Annaeus". In Smith, William (ed.). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology. Vol. 3. p. 782.

- ^ Sellars 2013, p. 109

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gill 1999, p. 43

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Colish 1985, p. 14

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Asmis, Bartsch & Nussbaum 2012, p. xv

- ^ Jump up to: a b Colish 1985, p. 49

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Asmis, Bartsch & Nussbaum 2012, p. xvi

- ^ Colish 1985, p. 41

- ^ Jump up to: a b Asmis, Bartsch & Nussbaum 2012, p. xxiii

- ^ Asmis, Bartsch & Nussbaum 2012, p. xx

- ^ Laarmann 2013, p. 53

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gill 1999, p. 58

- ^ The chief modern proponent of this view is Otto Zwierlein, Die Rezitationsdramen Senecas, 1966.

- ^ George W.M. Harrison (ed.), Seneca in performance, London: Duckworth, 2000.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Reynolds, Griffin & Fantham 2012, p. 94

- ^ John G. Fitch, "Sense-pauses and Relative Dating in Seneca, Sophocles and Shakespeare," American Journal of Philology 102 (1981) 289–307.

- ^ A.J. Boyle, Tragic Seneca: An Essay in the Theatrical Tradition. London: Routledge, 1997.

- ^ Seneca, Lucius Annaeus. His Tenne Tragedies. Thomas Newton, ed. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1966, p. xlv. ASIN B000N3NP6K

- ^ G. Braden, Renaissance Tragedy and the Senecan Tradition, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1985.

- ^ Magill, Frank Northen (1989). Masterpieces of World Literature. Harper & Row Limited. p. vii. ISBN 0060161442.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Seneca: The Tragedies. JHU Press. 1994. p. xli. ISBN 0801849322.

- ^ Heil, Andreas; Damschen, Gregor (2013). Brill's Companion to Seneca: Philosopher and Dramatist. Brill. p. 594. ISBN 978-9004217089. "Medea is often considered the masterpiece of Seneca's earlier plays, [...]"

- ^ Sluiter, Ineke; Rosen, Ralph M. (2012). Aesthetic Value in Classical Antiquity. Brill. p. 399. ISBN 978-9004231672.

- ^ Brockett, O. (2003), History of the Theatre: Ninth Ed. Allyn and Bacon. p. 50

- ^ R Ferri ed., Octavia (2003) pp. 5–9

- ^ H J Rose, A Handbook of Latin Literature (London 1967) p. 375

- ^ R Ferri ed., Octavia (2003) p. 6

- ^ "Seneca: On Clemency". Thelatinlibrary.com. Retrieved 26 July 2011.

- ^ "Apocryphal epistles". Earlychristianwritings.com. 2 February 2006. Retrieved 26 July 2011.

- ^ Joseph Barber Lightfoot (1892) St Paul and Seneca Dissertations on the Apostolic Age

- ^ Jump up to: a b Laarmann 2013, p. 54 citing Quintilian, Institutio Oratoria, x.1.126f; Aulus Gellius, Noctes Atticae, xii. 2.

- ^ Moses Hadas. The Stoic Philosophy of Seneca, 1958. 1.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Laarmann 2013, p. 54

- ^ Jump up to: a b Laarmann 2013, p. 55

- ^ Wilson 2014, p. 218

- ^ Jump up to: a b Wilson 2014, p. 219

- ^ Ker 2009, p. 197 citing Dante, Inf., 4.141

- ^ Ker 2009, pp. 221–222

- ^ Laarmann 2013, p. 59

- ^ "Pseudo-Seneca". www.bml.firenze.sbn.it.

- ^ István Pieter Bejczy, The Cardinal Virtues in the Middle Ages: A Study in Moral Thought from the Fourth to the Fourteenth Century, Brill, 2011, pp. 55–56.

- ^ GoodReads (retrieved 5 November 2021)

- ^ Richard Mott Gummere, Seneca the philosopher, and his modern message, p. 97.

- ^ Gummere, Seneca the philosopher, and his modern message, p. 106.

- ^ Moses Hadas. The Stoic Philosophy of Seneca, 1958. 3.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Campbell 1969, p. 11

- ^ Available in English as Girolamo Cardano, Nero: an Exemplary Life Inkstone, 2012

- ^ Siraisi, Nancy G. (2007). History, Medicine, and the Traditions of Renaissance Learning. University of Michigan Press. pp. 157–158.

- ^ Lydia Motto, Anna Seneca on Trial: The Case of the Opulent Stoic The Classic Journal, Vol. 61, No. 6 (1966) pp. 254–258

- ^ Lydia Motto, Anna Seneca on Trial: The Case of the Opulent Stoic The Classic Journal, Vol. 61, No. 6 (1966) p. 257

- ^ Nussbaum, M. (1996). The Therapy of Desire. Princeton University Press

- ^ Nussbaum, M. (1999). Cultivating Humanity: A Classical Defense of Reform in Liberal Education. Harvard University Press[ISBN missing][page needed]

- ^ Harpham, E. (2004). Gratitude in the History of Ideas, 19–37 in M. A. Emmons and M. E. McCulloch, editors, The Psychology of Gratitude, Oxford University Press.[ISBN missing]

- ^ "Seneca". IMDb.

- ^ Gioia, Dana (1992). "Introduction". In Slavitt, David R. (ed.). Seneca: The Tragedies. JHU Press. p. xviii.

- ^ Ker 2009, p. 220

- ^ Bridges, Robert (1894). Nero, Part II. From the death of Burrus to the death of Seneca, comprising the conspiracy of Piso. George Bell and Sons.

- ^ Cyrino, Monica Silveira (2008). Rome, season one: History makes television. Blackwell. p. 195.

- ^ Citti 2015, p. 316

- ^ Proud, Linda (2018). Chariot of the Soul. Oxford: Godstow Press. ISBN 978-1907651137. OCLC 1054834598.

- ^ "'Seneca — on the Creation of Earthquakes' Review: John Malkovich Travels Back to Nero's Rome in Misconceived Historical Fantasy". The Hollywood Reporter. 20 February 2023.

- ^ "'Seneca - on the Creation of Earthquakes': Berlin Review".

References[edit]

- Asmis, Elizabeth; Bartsch, Shadi; Nussbaum, Martha C. (2012), "Seneca and his World", in Kaster, Robert A.; Nussbaum, Martha C. (eds.), Seneca: Anger, Mercy, Revenge, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0226748429

- Braund, Susanna (2015), "Seneca Multiplex", in Bartsch, Shadi; Schiesaro, Alessandro (eds.), The Cambridge Companion to Seneca, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1107035058

- Campbell, Robin (1969), "Introduction", Letters from a Stoic, Penguin, ISBN 0140442103

- Citti, Francesco (2015), "Seneca and the Moderns", in Bartsch, Shadi; Schiesaro, Alessandro (eds.), The Cambridge Companion to Seneca, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1107035058

- Colish, Marcia L. (1985), The Stoic Tradition from Antiquity to the Early Middle Ages, vol. 1, Brill, ISBN 9004072675

- Gill, Christopher (1999), "The School in the Roman Imperial Period", in Inwood, Brad (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to the Stoics, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0521779855

- Habinek, Thomas (2013), "Imago Suae Vitae: Seneca's Life and Career", in Heil, Andreas; Damschen, Gregor (eds.), Brill's Companion to Seneca: Philosopher and Dramatist, Brill, ISBN 978-9004154612

- Ker, James (2009), The Deaths of Seneca, Oxford University Press

- Laarmann, Mathias (2013), "Seneca the Philosopher", in Heil, Andreas; Damschen, Gregor (eds.), Brill's Companion to Seneca: Philosopher and Dramatist, Brill, ISBN 978-9004154612

- Reynolds, L. D.; Griffin, M. T.; Fantham, E. (2012), "Annaeus Seneca (2), Lucius", in Hornblower, S.; Spawforth, A.; Eidinow, E. (eds.), The Oxford Classical Dictionary, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0199545568

- Sellars, John (2013), "Context: Seneca's Philosophical Predecessors and Contemporaries", in Heil, Andreas; Damschen, Gregor (eds.), Brill's Companion to Seneca: Philosopher and Dramatist, Brill, ISBN 978-9004154612

- Wilson, Emily R. (2014), The Greatest Empire: A Life of Seneca, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0199926640

Further reading[edit]

- Seneca, Lucius Annaeus. Anger, Mercy, Revenge. trans. Robert A. Kast and Martha C. Nussbaum. Chicago, IL. University of Chicago Press, 2010. ISBN 978-0226748412

- Seneca, Lucius Annaeus. Hardship and Happiness. trans. Elaine Fantham, Harry M. Hine, James Ker, and Gareth D. Williams. Chicago, IL. University of Chicago Press, 2014. ISBN 978-0226748320

- Seneca, Lucius Annaeus. Natural Questions. trans. Harry M. Hine. Chicago, IL. University of Chicago Press, 2010. ISBN 978-0226748382

- Seneca, Lucius Annaeus. On Benefits. trans. Miriam Griffin and Brad Inwood. Chicago, IL. University of Chicago Press, 2011. ISBN 978-0226748405

- Seneca: The Tragedies. Various translators, ed. David R. Slavitt. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2 vols, 1992–1994. ISBN 978-0801843099, 978-0801849329

- Seneca: Tragedies. Ed. & transl. John G. Fitch. Loeb Classical Library, Harvard University Press, 2 vols, 2nd edn. 2018. ISBN 978-0674997172, 978-0674997189

- Cunnally, John, “Nero, Seneca, and the Medallist of the Roman Emperors”, Art Bulletin, Vol. 68, No. 2 (June 1986), pp. 314–317

- Di Paola, O. (2015), "Connections between Seneca and Platonism in Epistulae ad Lucilium 58", Athens: ATINER'S Conference Paper Series, No: PHI2015-1445.

- Fitch, John G. (ed), Seneca. Oxford University Press, 2008. ISBN 978-0199282081. A collection of essays by leading scholars.

- Gloyn, Liz (2019). Tracking classical monsters in popular culture. London. ISBN 978-1784539344. OCLC 1081388471.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Griffin, Miriam T., Seneca: A Philosopher in Politics. Oxford University Press, 1976. ISBN 978-0198147749. Still the standard biography.

- Holiday, Ryan; Hanselman, Stephen (2020). "Seneca the Striver". Lives of the Stoics. New York: Portfolio/Penguin. pp. 184–207. ISBN 978-0525541875.

- Inwood, Brad, Reading Seneca. Stoic Philosophy at Rome, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

- Lucas, F. L., Seneca and Elizabethan Tragedy (Cambridge University Press, 1922; paperback 2009, ISBN 978-1108003582); on Seneca the man, his plays, and the influence of his tragedies on later drama.

- Mitchell, David. Legacy: The Apocryphal Correspondence between Seneca and Paul Archived 2 March 2021 at the Wayback Machine Xlibris Corporation 2010[self-published source]

- Motto, Anna Lydia, ”Seneca on Death and Immortality“, The Classical Journal, Vol. 50, No. 4 (Jan. 1955), pp. 187–189

- Motto, Anna Lydia, "Seneca on Trial: The Case of the Opulent Stoic", The Classical Journal, Vol. 61, No. 6 (March 1966), pp. 254–258

- Sevenster, J.N., Paul and Seneca, Novum Testamentum, Supplements, Vol. 4, Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1961; a comparison of Seneca and the apostle Paul, who were contemporaries.

- Shelton, Jo-Ann, Seneca's Hercules Furens: Theme, Structure and Style, Göttingen : Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1978. ISBN 3525251459. A revision of the author's doctoral thesis at the University of California, Berkeley, 1974.

- Wilson, Emily, Seneca: Six Tragedies. Oxford World's Classics. Oxford University Press, 2010.

External links[edit]

- Seneca's Dialogues, translated by Aubrey Stewart at Standard Ebooks

- Works by Seneca the Younger at Perseus Digital Library

- Vogt, Katja. "Seneca". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Wagoner, Robert. "Seneca". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Original texts of Seneca's works at 'The Latin Library'

- Works by Seneca the Younger in eBook form at Standard Ebooks

- Works by Seneca the Younger at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Seneca the Younger at Internet Archive

- Works by Seneca the Younger at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Collection of works of Seneca the Younger at Wikisource

- Seneca's essays and letters in English (at Stoics.com)

- List of commentaries of Seneca's Letters

- Incunabula (1478) of Seneca's works in the McCune Collection

- Seneca's Tragedies and the Elizabethan Drama

- SORGLL: Seneca, Thyestes 766–804 Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, read by Katharina Volk, Columbia University. Society for the Oral reading of Greek and Latin Literature (SORGLL)

- Digitized works by Lucius Annaeus Seneca at Biblioteca Digital Hispánica, Biblioteca Nacional de España

- Guide to Seneca, Lucius Annaeus, Spurious works. Manuscript, ca. 1450 at the University of Chicago Special Collections Research Center

- Digitized Edition of Seneca's Opera Omnia from 1503 (Venice) at E-rara.ch

- Seneca the Younger

- 0s BC births

- 65 deaths

- 1st-century executions

- 1st-century philosophers

- 1st-century Romans

- 1st-century writers

- Ancient Roman tragic dramatists

- Suicides in Ancient Rome

- Annaei

- Ethicists

- Executed philosophers

- Executed writers

- Forced suicides

- Letter writers in Latin

- Male dramatists and playwrights

- Male essayists

- Members of the Pisonian conspiracy

- People executed by the Roman Empire

- People from Córdoba, Spain

- Ancient Roman encyclopedists

- Ancient Roman satirists

- Roman-era Stoic philosophers

- Romans from Hispania

- Silver Age Latin writers

- Suffect consuls of Imperial Rome

- Roman-era philosophers in Rome