O. M. Wozencraft

Oliver M. Wozencraft (July 26, 1814 – November 22, 1887) was a prominent early American settler in California. He had substantial involvement in negotiating treaties between California Native American Indian tribes and the United States of America.[1][2] Later, Wozencraft promoted a plan to provide irrigation to the Imperial Valley.[3][4]

Life

[edit]Early years

[edit]Wozencraft was born in Clermont County, Ohio, June 26, 1814.[5] He graduated with a degree in medicine from St. Joseph's College in Bardstown, Kentucky.[3] Wozencraft married Lamiza A. Ramsey (June 13, 1818 – August 30, 1905) in Nashville, Tennessee on February 23, 1837.[6][7] In 1848, leaving his wife and three small children in New Orleans directly after a cholera epidemic,[8] he relocated to Brownsville, Texas.[9]

After the cholera epidemic swept Brownsville in February through April 1849,[10] upon hearing news of gold being discovered, Wozencraft decided to seek his fortune in California.[3][8] Wozencraft arrived at Yuma, Arizona in May 1849, crossed the Colorado Desert in difficult circumstances, then arrived in California.[11]

California Constitutional Convention

[edit]Wozencraft settled in Stockton, California and was elected as delegate to the California Constitutional Convention in Monterey in 1849 representing the district of San Joaquin.[12]

Wozencraft spoke against the admission of African Americans to California:

We have declared, by a unanimous vote, that neither slavery nor involuntary servitude shall ever exist in this State. I desire now to cast my vote in favor of the proposition just submitted, prohibiting the negro race from coming amongst us; and this I profess to do as a philanthropist, loving my kind, and rejoicing in their rapid march toward perfectibility. If there was just reason why slavery should not exist in this land, there is just reason why that part of the family of man, who are so well adapted for servitude, should be excluded from amongst us. It would appear that the all-wise Creator has created the negro to serve the white race. We see evidence of this wherever they are brought in contact; we see the instinctive feeling of the negro is obedience to the white man, and, in all instances, he obeys him, and is ruled by him. If you would wish that all mankind should be free, do not bring the two extremes in the scale of organization together; do not bring the lowest in contact with the highest, for be assured the one will rule and the other must serve.

— Oliver M. Wozencraft[13]

He also moved that a two term limit apply to the position of Governor of California. That question was debated then rejected.[14]

Wozencraft's signature appears on the handwritten parchment copy of the constitution signed by the delegates on October 13, 1849.[15]

Treaties with Native Americans

[edit]

On July 8, 1850, President Millard Fillmore appointed Wozencraft as an Indian Agent of the United States.[3][18] Salary and expenses were not provided to Wozencraft for this appointment. On October 15, 1850, his title as Indian Agent was suspended and he, Redick McKee and George W. Barbour were appointed "commissioners 'to hold treaties with various Indian tribes in the State of California,' as provided in the act of Congress approved September 30, 1850." In that role Wozencraft was paid eight dollars per day plus ten cents per mile travelled.[19]

Between March 19, 1851, and January 7, 1852, Wozencraft, McKee and Barbour traversed California and negotiated 18 treaties with Native American tribes.[2] The treaties were submitted to the United States Senate on June 1, 1852. They were considered and rejected for ratification by the Senate in closed session. The treaties were then sealed from public record until January 18, 1905.[20][21][22]

Fillmore removed Wozencraft's standing as an Indian Agent on August 28, 1852.[21]

Imperial Valley Irrigation

[edit]Wozencraft was an advocate for creating a gravity-fed canal from the Colorado River to provide irrigation to the Salton Sink area of the Colorado Desert (now known as the Imperial Valley). Around 1854 to 1855 he hired Ebenezer Hadley, County Surveyor of Los Angeles and Deputy County Surveyor of San Bernardino, to survey a route for the canal.[23][24] In 1859 Wozencraft successfully lobbied the California State Legislature to provisionally allocate 3,000,000 acres (12,141 km2) of the Colorado Desert to himself for the scheme.[4][24]

Wozencraft required passage of federal legislation (e.g. H.R.3219[23]) to finalize the land allocation approved by the state legislature. This would allow him to secure capital to complete the project. He unsuccessfully lobbied the United States Congress for this allocation for the remainder of his life.[11][24]

Death and legacy

[edit]

Wozencraft died of a heart attack on November 22, 1887, in a boardinghouse in Washington, D.C.[11] He had been in Washington to again present a Colorado Desert irrigation scheme bill to Congress. Just prior to his death the bill had been killed in committee. In committee the bill was described as a "fantastic folly of an old man".[11]

Work began on the Alamo Canal 13 years after Wozencraft's death, ultimately providing irrigation to the Imperial Valley in a manner similar to that first proposed by Wozencraft almost 50 years earlier.[25] He has been declared the "Father of the Imperial Valley."[4][5][26]

Modern evaluations of the treaties he negotiated with California Native Americans are critical:

Taken all together, one cannot imagine a more poorly conceived, more inaccurate, less informed, and less democratic process than the making of the 18 treaties in 1851-52 with the California Indians. It was a farce from beginning to end.[22]

Nineteenth century evaluations are likewise scathing:

There was a very general impression in the state, and apparently pretty well founded, that [Wozencraft, McKee and Barbour] knew little about the country and still less about the Indians; and that everything they did was a mistake and almost everything in excess of their powers. They appear to have traveled about in considerable style and at very great expense, but accomplished nothing of importance. They made presents and promises in abundance, but got nothing of value in return. None of their treaties were approved; and nearly all the debts they contracted were repudiated as unauthorized. The reservations they established were nearly, if not entirely, useless and very unpopular...[27]

Wozencraft is buried at the San Bernardino Pioneer Memorial Cemetery.[28]

References

[edit]- ^ RICHARD L. CARRICO (Summer 1980). "San Diego Indians and the Federal Government Years of Neglect, 1850-1865". The Journal of San Diego History. San Diego Historical Society. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- ^ a b Alban W. Hoopes, George W. Barbour. "Journal of George W. Barbour, May 1, to October 4, 1851 II". Southwestern Historical Quarterly Online. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- ^ a b c d Starr, Kevin (1990). Material Dreams: Southern California Through the 1920s. Oxford University Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-19-507260-0. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- ^ a b c Robert L. Sperry (Winter 1975). "When the Imperial Valley Fought for its Life". The Journal of San Diego History. San Diego Historical Society. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- ^ a b Howe, Edgar F.; Hall, Wilbur Jay (1910). The story of the first decade in Imperial Valley, California. Imperial. p. 25, 27. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

wozencraft.

- ^ Whitley, Edythe Johns Rucker (1981). Marriages of Davidson County, Tennessee, 1789-1847. Clearfield. p. 163. ISBN 978-0-8063-0919-4. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ Durham, Walter T. (1997). Volunteer Forty-niners: Tennesseans and the California gold rush. Vanderbilt University Press. p. 121. ISBN 978-0-8265-1298-7. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- ^ a b Edmund Charles Wendt, M.D., ed. (1885). A treatise on Asiatic cholera. New York: William Wood. p. 79. Retrieved 6 June 2010.

brownsville cholera 1849 california emigrants.

- ^ Taze Lamb; Jessie Lamb (June 1938). "Dream of a Desert Paradise". Desert Magazine. pp. 22–23. Retrieved 4 June 2010.

- ^ Richard B. Marrin, Lorna Geer Sheppard, ed. (2009). Abstracts from the Northern Standard and The Red River District: August 26, 1848-December 20, 1851. Heritage Books. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-7884-4454-8. Retrieved 6 June 2010.

- ^ a b c d Stevens, Joseph E. (1990). Hoover Dam: An American Adventure. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-8061-2283-0. Retrieved 26 May 2010.

- ^ Thrapp, Dan L. (1991). Encyclopedia of Frontier Biography: P-Z. University of Nebraska Press. p. 1599. ISBN 978-0-8032-9420-2. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ Browne, John Ross (1850). Report of the debates in the Convention of California on the formation of the State Constitution. Washington, DC: Congress of the United States of America. p. 49. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

wozencraft negro.

- ^ Browne, John Ross (1850). Report of the debates in the Convention of California on the formation of the State Constitution. Washington, DC: Congress of the United States of America. p. 156. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

wozencraft moved the following.

- ^ "Records of the Constitutional Convention of 1849". California State Archives. California Secretary of State. Retrieved 27 May 2010.

- ^ "California -- One Hundred and Fifty Years Ago". Studies in the News. CALIFORNIA RESEARCH BUREAU CALIFORNIA STATE LIBRARY. Retrieved 14 June 2010.

- ^ "Text of Bidwell Treaty". Konkow Valley Band of Maidu. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- ^ DEPARTMENT OF INTERIOR'S RECENTLY RELEASED GUIDANCE ON TAKING LAND INTO TRUST FOR INDIAN TRIBES AND ITS RAMIFICATIONS (PDF) (Report). COMMITTEE ON NATURAL RESOURCES, U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES, ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION. 2008. p. 41. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- ^ A.S. Loughery, Acting Commissioner (1850). Letter to O.M. Wozencraft, Eedick McKee and George W. Barbour. Washington, DC: Department Of The Interior. p. 152. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ Johnston-Dodds, Kimberly (2002). Early California Laws and Policies Related to California Indians (PDF). California Research Bureau, California State Library. pp. 23–24. ISBN 1-58703-163-9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 December 2017. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ a b Journal of the executive proceedings of the Senate of the United States of America. United States Congress. July 8, 1852. p. 392,446. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- ^ a b Heizer, Robert F. (1972). The Eighteen Unratified Treaties of 1851-52. Berkeley: Archaeological Research Facility. pp. 50–56.

- ^ a b Congressional serial set, Issue 2439. Washington D.C.: United States Government Printing Office. 1885. p. 219. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- ^ a b c Rudy, Alan (1995). "3" (PDF). Environmental Conditions, Negotiations and Crises: The Political Economy of Agriculture in the Imperial Valley of California, 1850-1993 (Ph.D. in Sociology thesis). Retrieved 26 May 2010.

- ^ Laflin, Pat. "THE SALTON SEA CALIFORNIA'S OVERLOOKED TREASURE" (PDF). Coachella Valley Historical Society. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 May 2010. Retrieved 1 June 2010.

- ^ Romer, M.A., Margaret (1922). "A History of Calexico". Historical Society of Southern California. 12 (2). Los Angeles: 29. Retrieved 6 June 2010.

- ^ Hittell, Theodore Henry (1898). History of California. Vol. 3. San Francisco: N. J. Stone and Company. p. 902. Retrieved 28 May 2010.

- ^ "Pioneers of San Bernardino: Oliver M. Wozencraft". City of San Bernardino. Retrieved 15 March 2011.

Further reading

[edit]- Wozencraft, Oliver M. (June 1875). Gibbons, Henry (ed.). "The Dead Brought to Life with Animal Magnetism". Pacific Medical and Surgical Journal. 1. 18: 221.

- Wozencraft letter to Hon. Luke Lea, Commissioner Indian Affairs, Washington requesting $500,000 to cover treaty commitments to California Native Americans. Wozencraft, Oliver M. (1851–1852). EXECUTIVE DOCUMENTS THE SENATE OF THE UNITED STATES. pp. 7–8.

- Wozencraft accused of demanding kickback from contract to supply cattle to Native American bands as part of treaty negotiations. Secrest, William B. (2002). When the great spirit died: the destruction of the California Indians, 1850-1860. Word Dancer Press. p. 165. ISBN 978-1-884995-40-8.

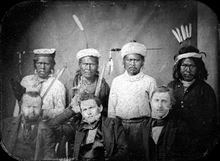

- Magazine article with Wozencraft claims of finding baby Shasta abandoned by mother; picture of Shasta in 1882. Taze Lamb; Jessie Lamb (June 1938). "Dream of a Desert Paradise". Desert Magazine. pp. 22–28. Retrieved 4 June 2010.

- Gunfight with Willis brothers. "SAN FRANCISCO NEWS". Sacramento Daily Union. November 27, 1862. Retrieved 4 June 2010. Willis accuses Wozencraft of being drunk, abusive and the first to draw a pistol. "The Wozencraft and Willis Difficulty". Sacramento Daily Union. 2 December 1862. p. 3. Retrieved 28 June 2011.

- 1864 newspaper article by Mark Twain describing Wozencraft's oration in praise of the Democratic Party and Secession; "His speech was simply a rehash of all the whinings and hypocrisy of Copperheads since the conflict began."Twain, Mark (August 3, 1864). "Democratic Meeting at Hayes' Park". The San Francisco Daily Morning Call. Retrieved 22 June 2010.

External links

[edit]- Treaty of Temecula

Media related to O. M. Wozencraft at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to O. M. Wozencraft at Wikimedia Commons