James Madison

James Madison | |

|---|---|

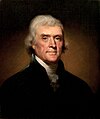

1816 portrait | |

| 4th President of the United States | |

| In office March 4, 1809 – March 4, 1817[1] | |

| Vice President |

|

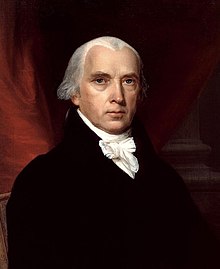

| Preceded by | Thomas Jefferson |

| Succeeded by | James Monroe |

| 5th United States Secretary of State | |

| In office May 2, 1801 – March 3, 1809[3] | |

| President | Thomas Jefferson |

| Preceded by | John Marshall |

| Succeeded by | Robert Smith |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Virginia | |

| In office March 4, 1789 – March 4, 1797[4] | |

| Preceded by | Constituency established |

| Succeeded by | John Dawson |

| Constituency |

|

| Delegate from Virginia to the Congress of the Confederation | |

| In office November 6, 1786 – October 30, 1787[5] | |

| In office March 1, 1781 – November 1, 1783 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | James Madison Jr. March 16, 1751 Port Conway, Virginia |

| Died | June 28, 1836 (aged 85) Montpelier, Orange County, Virginia, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic–Republican |

| Height | 5 ft 4 in (163 cm)[6] |

| Spouse | |

| Parents | |

| Education | College of New Jersey (BA) |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Branch/service | Virginia militia |

| Years of service | 1775 - 1776 1814 |

| Rank | Colonel Commander in Chief |

| Unit | Orange County Militia |

| Battles/wars | American Revolutionary War |

James Madison (March 16, 1751[b] – June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Father who served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison was popularly acclaimed the "Father of the Constitution" for his pivotal role in drafting and promoting the Constitution of the United States and the Bill of Rights.

Madison was born into a prominent slave-owning planter family in Virginia. He served as a member of the Virginia House of Delegates and the Continental Congress during and after the American Revolutionary War. Dissatisfied with the weak national government established by the Articles of Confederation, he helped organize the Constitutional Convention, which produced a new constitution designed to strengthen republican government against democratic assembly. Madison's Virginia Plan was the basis for the convention's deliberations, and he was an influential voice at the convention. He became one of the leaders in the movement to ratify the Constitution and joined Alexander Hamilton and John Jay in writing The Federalist Papers, a series of pro-ratification essays that remains prominent among works of political science in American history. Madison emerged as an important leader in the House of Representatives and was a close adviser to President George Washington.

During the early 1790s, Madison opposed the economic program and the accompanying centralization of power favored by Secretary of the Treasury Hamilton. Alongside Thomas Jefferson, he organized the Democratic–Republican Party in opposition to Hamilton's Federalist Party. After Jefferson was elected president in 1800, Madison served as his Secretary of State from 1801 to 1809 and supported Jefferson in the case of Marbury v. Madison. While Madison was Secretary of State, Jefferson made the Louisiana Purchase, and later, as President, Madison oversaw related disputes in the Northwest Territories.

Madison was elected president in 1808. Motivated by desire to acquire land held by Britain, Spain, and Native Americans, and after diplomatic protests with a trade embargo failed to end British seizures of American shipped goods, Madison led the United States into the War of 1812. Although the war ended inconclusively, many Americans viewed the war's outcome as a successful "second war of independence" against Britain. Madison was re-elected in 1812, albeit by a smaller margin. The war convinced Madison of the necessity of a stronger federal government. He presided over the creation of the Second Bank of the United States and the enactment of the protective Tariff of 1816. By treaty or through war, Native American tribes ceded 26,000,000 acres (11,000,000 ha) of land to the United States under Madison's presidency.

Retiring from public office at the end of his presidency in 1817, Madison returned to his plantation, Montpelier, and died there in 1836. During his lifetime, Madison was a slave owner. In 1783, to prevent a slave rebellion at Montpelier, Madison freed one of his slaves. He did not free any slaves in his will. Among historians, Madison is considered one of the most important Founding Fathers of the United States. Leading historians have generally ranked him as an above-average president, although they are critical of his endorsement of slavery and his leadership during the War of 1812. Madison's name is commemorated in many landmarks across the nation, both publicly and privately, with prominent examples including Madison Square Garden, James Madison University, the James Madison Memorial Building, and the USS James Madison.

Early life and education

James Madison Jr. was born on March 16, 1751 (March 5, 1750, Old Style), at Belle Grove Plantation near Port Conway in the Colony of Virginia, to James Madison Sr. and Eleanor Madison. His family had lived in Virginia since the mid-17th century.[7] Madison's maternal grandfather, Francis Conway, was a prominent planter and tobacco merchant.[8] His father was a tobacco planter who grew up on a plantation, then called Mount Pleasant, which he inherited upon reaching adulthood. With an estimated 100 slaves[7] and a 5,000-acre (2,000 ha) plantation, Madison's father was among the largest landowners in Virginia's Piedmont.[9]

In the early 1760s, the Madison family moved into a newly built house that they named Montpelier.[10] Madison grew up as the oldest of twelve children,[11] with seven brothers and four sisters, though only six lived to adulthood.[10] Of the surviving three brothers (Francis, Ambrose, and William) and three sisters (Nelly, Sarah, and Frances), it was Ambrose who would eventually help to manage Montpelier for both his father and older brother until his own death in 1793.[12] President Zachary Taylor was a descendant of Elder William Brewster, a Pilgrim leader of the Plymouth Colony, a Mayflower immigrant, and a signer of the Mayflower Compact; and Isaac Allerton Jr., a colonial merchant, colonel, and son of Mayflower Pilgrim Isaac Allerton and Fear Brewster. Taylor's second cousin through that line was Madison.[13]

From age 11 to 16, Madison studied under Donald Robertson, a Scottish instructor who served as a tutor for several prominent planter families in the South. Madison learned mathematics, geography, and modern and classical languages, becoming exceptionally proficient in Latin. [14][10] At age 16, Madison returned to Montpelier, where he studied under the Reverend Thomas Martin to prepare for college. Unlike most college-bound Virginians of his day, Madison did not attend the College of William and Mary, where the lowland Williamsburg climate—thought to be more likely to harbor infectious disease—might have strained his sensibilities concerning his own health.[15] Instead, in 1769, he enrolled at the College of New Jersey (later renamed Princeton University).[16]

His college studies included Latin, Greek, theology, and the works of the Enlightenment.[17] Emphasis was placed on both speech and debate; Madison was a leading member of the American Whig–Cliosophic Society, which competed on campus with a political counterpart, the Cliosophic Society.[18] During his time at Princeton, Madison's closest friend was future Attorney General William Bradford.[19] Along with classmate Aaron Burr, Madison undertook an intense program of study and completed the college's three-year Bachelor of Arts degree in two years, graduating in 1771.[20] Madison had contemplated either entering the clergy or practicing law after graduation but instead remained at Princeton to study Hebrew and political philosophy under the college's president, John Witherspoon.[7] He returned home to Montpelier in early 1772.[21]

Madison's ideas on philosophy and morality were strongly shaped by Witherspoon, who converted him to the philosophy, values, and modes of thinking of the Age of Enlightenment. Biographer Terence Ball wrote that at Princeton, Madison "was immersed in the liberalism of the Enlightenment, and converted to eighteenth-century political radicalism. From then on James Madison's theories would advance the rights of happiness of man, and his most active efforts would serve devotedly the cause of civil and political liberty."[22]

After returning to Montpelier, without a chosen career, Madison served as a tutor to his younger siblings.[23] He began to study law books in 1773, asking his friend Bradford, a law apprentice, to send him a written plan of study. Madison had acquired an understanding of legal publications by 1783. He saw himself as a law student but not a lawyer. Madison did not apprentice himself to a lawyer and never joined the bar.[24] Following the Revolutionary War, he spent time at Montpelier in Virginia studying ancient democracies of the world in preparation for the Constitutional Convention.[10][25] Madison suffered from episodes of mental exhaustion and illness with associated nervousness, which often caused temporary short-term incapacity after periods of stress. However, he enjoyed good physical health until his final years.[26]

American Revolution and Articles of Confederation

During the 1760s and 1770s, American Colonists protested tightened British tax, monetary, and military laws forced on them by Parliament.[27] In 1765, the British Parliament passed the Stamp Act, which caused strong opposition by the colonists and began a conflict that would culminate in the American Revolution.[28][29] The American Revolutionary War broke out on April 19, 1775, and was ended by the Treaty of Paris signed on September 3, 1783.[28][30][31] The colonists formed three prominent factions: Loyalists, who continued to back King George III of the United Kingdom; a significant neutral faction without firm commitments to either Loyalists or Patriots; and the Patriots, whom Madison joined, under the leadership of the Continental Congress.[32][33] Madison believed that Parliament had overstepped its bounds by attempting to tax the American colonies, and he sympathized with those who resisted British rule.[34] Historically, debate about the consecration of bishops was ongoing and eventual legislation was passed in the British Parliament (subsequently called the Consecration of Bishops Abroad Act 1786) to allow bishops to be consecrated for an American church outside of allegiance to the British Crown.[35] Both in the United States and in Canada, the new Anglican churches began incorporating more active forms of polity in their own self-government, collective decision-making, and self-supported financing; these measures would be consistent with separation of religious and secular identities.[36] Madison believed these measures to be insufficient, and also favored disestablishing the Anglican Church in Virginia; Madison believed that tolerance of an established religion was detrimental not only to freedom of religion but also because it encouraged excessive deference to any authority which might be asserted by an established church.[37]

After returning to Montpelier in 1774, Madison took a seat on the local Committee of Safety, a pro-revolution group that oversaw the local Patriot militia.[38] In October 1775, he was commissioned as the colonel of the Orange County militia, serving as his father's second-in-command until he was elected as a delegate to the Fifth Virginia Convention, which was charged with producing Virginia's first constitution.[5] Although Madison never battled in the Revolutionary War, he did rise to prominence in Virginia politics as a wartime leader.[39] At the Virginia constitutional convention, he convinced delegates to alter the Virginia Declaration of Rights originally drafted on May 20, 1776, to provide for "equal entitlement", rather than mere "tolerance", in the exercise of religion.[40] With the enactment of the Virginia constitution, Madison became part of the Virginia House of Delegates, and he was subsequently elected to the Virginia governor's Council of State,[41] where he became a close ally of Governor Thomas Jefferson.[42] On July 4, 1776, the United States Declaration of Independence was formally printed, declaring the 13 American states an independent nation.[43][44]

Madison participated in the debates concerning the Articles of Confederation[45] in November 1777, contributing to the discussion of religious freedom affecting the drafting of the Articles, though his signature was not required for adopting the Articles of Confederation. Madison had proposed liberalizing the article on religious freedom, but the larger Virginia Convention stripped the proposed constitution of the more radical language of "free expression" of faith to the less controversial mention of highlighting "tolerance" within religion. Other amendments by the committee and the entire Convention included the addition of a section on the right to a uniform government.[46] Madison again served on the Council of State, from 1777 to 1779, when he was elected to the Second Continental Congress, the governing body of the United States.[c]

During Madison's term in Congress from 1780 to 1783, the U.S. faced a difficult war against Great Britain, as well as runaway inflation, financial troubles, and a lack of cooperation between the different levels of government. According to historian J. C. A. Stagg, Madison worked to become an expert on financial issues, becoming a legislative workhorse and a master of parliamentary coalition building.[48] Frustrated by the failure of the states to supply needed requisitions, Madison proposed to amend the Articles of Confederation to grant Congress the power to independently raise revenue through tariffs on imports.[49] Though General George Washington, Congressman Alexander Hamilton, and other leaders also favored the tariff amendment, it was defeated because it failed to win the ratification of all thirteen states.[50] While a member of Congress, Madison was an ardent supporter of a close alliance between the United States and France. As an advocate of westward expansion, he insisted that the new nation had to ensure its right to navigation on the Mississippi River and control of all lands east of it in the Treaty of Paris, which ended the Revolutionary War.[51] Following his term in Congress, Madison won election to the Virginia House of Delegates in 1784.[52]

Ratification of the Constitution

As a member of the Virginia House of Delegates, Madison continued to advocate for religious freedom, and, along with Jefferson, drafted the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom. That amendment, which guaranteed freedom of religion and disestablished the Church of England, was passed in 1786.[53] Madison also became a land speculator, purchasing land along the Mohawk River in partnership with another Jefferson protégé, James Monroe.[54] Throughout the 1780s, Madison became increasingly worried about the disunity of the states and the weakness of the central government after the end of the Revolutionary War.[55] He believed that direct democracy caused social decay and that a Republican government would be effective against partisanship and factionalism.[56][57][58] He was particularly troubled by laws that legalized paper money and denied diplomatic immunity to ambassadors from other countries.[59] Madison was also concerned about the lack of ability in Congress to capably create foreign policy, protect American trade, and foster the settlement of the lands between the Appalachian Mountains and the Mississippi River.[60] As Madison wrote, "a crisis had arrived which was to decide whether the American experiment was to be a blessing to the world, or to blast for ever the hopes which the republican cause had inspired."[61] Madison committed to an intense study of law and political theory and also was influenced by Enlightenment texts sent by Jefferson from France.[62] Madison especially sought out works on international law and the constitutions of "ancient and modern confederacies" such as the Dutch Republic, the Swiss Confederation, and the Achaean League.[63] He came to believe that the United States could improve upon past republican experiments by its size which geographically combined 13 colonies; with so many competing interests, Madison hoped to minimize the abuses of majority rule.[64] Additionally, navigation rights to the major trade routes accessed by the Mississippi River highly concerned Madison. He opposed the proposal by John Jay that the United States concede claims to the river for 25 years, and, according to historian Ralph Ketcham, Madison's desire to fight the proposal was a major motivation in his to return to Congress in 1787.[65]

Leading up to the 1787 ratification debates for the Constitution,[67] Madison worked with other members of the Virginia delegation, especially Edmund Randolph and George Mason, to create and present the Virginia Plan, an outline for a new federal constitution.[68] It called for three branches of government (legislative, executive, and judicial), a bicameral Congress (consisting of the Senate and the House of Representatives) apportioned by population, and a federal Council of Revision that would have the right to veto laws passed by Congress.[69] The Virginia Plan did not explicitly lay out the structure of the executive branch, but Madison himself favored a strong single executive.[70] Many delegates were surprised to learn that the plan called for the abrogation of the Articles and the creation of a new constitution, to be ratified by special conventions in each state, rather than by the state legislatures. With the assent of prominent attendees such as Washington and Benjamin Franklin, the delegates agreed in a secret session that the abrogation of the Articles and the creation of a new constitution was a plausible option and began scheduling the process of debating its ratification in the individual states.[71] As a compromise between small and large states, large states got a proportional House, while the small states got equal representation in the Senate.[72]

After the Philadelphia Convention ended in September 1787, Madison convinced his fellow congressmen to remain neutral in the ratification debate and allow each state to vote on the Constitution.[73] Those who supported the Constitution were called Federalists, that included Madison.[74] Throughout the United States, opponents of the Constitution, known as Anti-Federalists, began a public campaign against ratification.[74] In response, starting in October 1787,[75] Hamilton and John Jay, both Federalists, began publishing a series of pro-ratification newspaper articles in New York.[76] After Jay dropped out of the project, Hamilton approached Madison, who was in New York on congressional business, to write some of the essays.[77] The essays were published under the pseudonym of Publius.[78][79] The trio produced 85 essays known as The Federalist Papers.[79] The 85 essays were divided into two parts, 36 letters were against the Articles of Confederation, and 49 letters that favored the new Constitution.[75] The articles were also published in book form and used by the supporters of the Constitution in the ratifying conventions. Federalist No. 10, Madison's first contribution to The Federalist Papers, became highly regarded in the 20th century for its advocacy of representative democracy.[80] In it, Madison describes the dangers posed by the majority factions and argues that their effects can be limited through the formation of a large republic. He theorizes that in large republics the large number of factions that emerge will control their influence because no single faction can become a majority.[81][82] In Federalist No. 51, he goes on to explain how the separation of powers between three branches of the federal government, as well as between state governments and the federal government, establishes a system of checks and balances that ensures that no one institution would become too powerful.[83]

As the Virginia ratification convention began, Madison focused his efforts on winning the support of the relatively small number of undecided delegates.[84] His long correspondence with Randolph paid off at the convention, as Randolph announced that he would support unconditional ratification of the Constitution, with amendments to be proposed after ratification.[85] Though former Virginia governor Patrick Henry gave several persuasive speeches arguing against ratification, Madison's expertise on the subject he had long argued for allowed him to respond with rational arguments to Henry's anti-Federalist appeals.[86] Madison was also a defender of federal veto rights and, according to historian Ron Chernow "pleaded at the Constitutional Convention that the federal government should possess a veto over state laws".[87] In his final speech to the ratifying convention, Madison implored his fellow delegates to ratify the Constitution as it had been written, arguing that failure to do so would lead to the collapse of the entire ratification effort, as each state would seek favorable amendments.[88] On June 25, 1788, the convention voted 89–79 in favor of ratification. The vote came a week after New Hampshire became the ninth state to ratify, thereby securing the Constitution's adoption and with that, a new form of government.[89] The following January, Washington was elected the nation's first president.[90]

Congressman and party leader (1789–1801)

Election to Congress

After Virginia ratified the constitution, Madison returned to New York and resumed his duties in the Congress of the Confederation. After Madison was defeated in his bid for the Senate, and with concerns for both his political career and the possibility that Patrick Henry and his allies would arrange for a second constitutional convention, Madison ran for the House of Representatives.[91][92][93] Henry and the Anti-Federalists were in firm control of the General Assembly in the autumn of 1788.[93] At Henry's behest, the Virginia legislature designed to deny Madison a seat, and created congressional districts. Henry and his supporters ensured that Orange County was in a district heavily populated with Anti-Federalists, roughly three to one, to oppose Madison.[93][94] This practice is called gerrymandering.[93] Henry also recruited James Monroe, a strong challenger to Madison. [94] Locked in a difficult race against Monroe, Madison promised to support a series of constitutional amendments to protect individual liberties.[91] In an open letter, Madison wrote that, while he had opposed requiring alterations to the Constitution before ratification, he now believed that "amendments, if pursued with a proper moderation and in a proper mode ... may serve the double purpose of satisfying the minds of well-meaning opponents, and of providing additional guards in favor of liberty."[95] Madison's promise paid off, as in Virginia's 5th district election, he gained a seat in Congress with 57 percent of the vote.[4]

Madison became a key adviser to Washington, who valued Madison's understanding of the Constitution.[91] Madison helped Washington write his first inaugural address and also prepared the official House response to Washington's speech. He played a significant role in establishing and staffing the three Cabinet departments, and his influence helped Thomas Jefferson become the first Secretary of State.[96] At the start of the first Congress, he introduced a tariff bill similar to the one he had advocated for under the Articles of the Confederation,[97] and Congress established a federal tariff on imports by enacting the Tariff of 1789.[98] The following year, Secretary of the Treasury Hamilton introduced an ambitious economic program that called for the federal assumption of state debts and the funding of that debt through the issuance of federal securities. Hamilton's plan favored Northern speculators and was disadvantageous to states, such as Virginia, that had already paid off most of their debt; Madison emerged as one of the principal congressional opponents of the plan.[99] After prolonged legislative deadlock, Madison, Jefferson, and Hamilton agreed to the Compromise of 1790, which provided for the enactment of Hamilton's assumption plan, as part of the Funding Act of 1790. In return, Congress passed the Residence Act, which established the federal capital district of Washington, D.C., on the Potomac River.[100]

Bill of Rights

During the first Congress, Madison took the lead in advocating for several constitutional amendments to the Bill of Rights.[101] His primary goals were to fulfill his 1789 campaign pledge and to prevent the calling of a second constitutional convention, but he also hoped to safeguard the rights and liberties of the people against broad actions of Congress and individual states. He believed that the enumeration of specific rights would fix those rights in the public mind and encourage judges to protect them.[102][103] After studying more than two hundred amendments that had been proposed at the state ratifying conventions,[104] Madison introduced the Bill of Rights on June 8, 1789. His amendments contained numerous restrictions on the federal government and would protect, among other things, freedom of religion, freedom of speech, and the right to peaceful assembly.[105] While most of his proposed amendments were drawn from the ratifying conventions, Madison was largely responsible for proposals to guarantee freedom of the press, protect property from government seizure, and ensure jury trials.[104] He also proposed an amendment to prevent states from abridging "equal rights of conscience, or freedom of the press, or the trial by jury in criminal cases".[106]

To prevent a permanent standing federal army, Madison proposed the Second Amendment, which gave state-regulated militia groups and private citizens, the "right to bear arms." Madison and the Republicans desired a free government to be established by the consent of the governed, rather than by national military force. [107]

Madison's Bill of Rights faced little opposition; he had largely co-opted the Anti-Federalist goal of amending the Constitution but had avoided proposing amendments that would alienate supporters of the Constitution.[108] His amendments were mostly adopted by the House of Representatives as proposed, but the Senate made several changes.[109] Madison's proposal to apply parts of the Bill of Rights to the states was eliminated, as was his change to the Constitution's preamble which he thought would be enhanced by including a prefatory paragraph indicating that governmental power is vested by the people.[110] He was disappointed that the Bill of Rights did not include protections against actions by state governments,[d] but the passage of the document mollified some critics of the original constitution and shored up his support in Virginia.[104] Ten amendments were finally ratified on December 15, 1791, becoming known in their final form as the Bill of Rights.[112][e]

Founding the Democratic–Republican Party

After 1790, the Washington administration became polarized into two main factions. One faction, led by Jefferson and Madison, broadly represented Southern interests and sought close relations with France. This faction became the Democratic-Republican Party opposition to Secretary of the Treasury Hamilton. The other faction, led by Hamilton and the Federalists, broadly represented Northern financial interests and favored close relations with Britain.[114] In 1791, Hamilton introduced a plan that called for the establishment of a national bank to provide loans to emerging industries and oversee the money supply.[115] Madison and the Democratic-Republican Party fought back against Hamilton's attempt to expand the power of the Federal Government with the formation of a national bank. Therefore, they opposed Hamilton's plan and Madison argued that under the Constitution, Congress did not have the power to create a federally empowered national bank.[116] Despite Madison's opposition, Congress passed a bill to create the First Bank of the United States, which Washington signed into law in February 1791.[115] As Hamilton implemented his economic program and Washington continued to enjoy immense prestige as president, Madison became increasingly concerned that Hamilton would seek to abolish the federal republic in favor of a centralized monarchy.[117]

When Hamilton submitted his Report on Manufactures, which called for federal action to stimulate the development of a diversified economy, Madison once again challenged Hamilton's proposal.[118] Along with Jefferson, Madison helped Philip Freneau establish the National Gazette, a Philadelphia newspaper that attacked Hamilton's proposals.[119] In an essay published in the newspaper in September 1792, Madison wrote that the country had divided into two factions: his faction, which believed "that mankind are capable of governing themselves", and Hamilton's faction, which allegedly sought the establishment of an aristocratic monarchy and was biased in favor of the wealthy.[120] Those opposed to Hamilton's economic policies, including many former Anti-Federalists, continued to strengthen the ranks of the Democratic–Republican Party,[f] while those who supported the administration's policies supported Hamilton's Federalist Party.[122] In the 1792 presidential election, both major parties supported Washington for re-election, but the Democratic–Republicans sought to unseat Vice President John Adams. Because the Constitution's rules essentially precluded Jefferson from challenging Adams,[g] the party backed New York Governor George Clinton for the vice presidency, but Adams won nonetheless.[124]

With Jefferson out of office after 1793, Madison became the de facto leader of the Democratic–Republican Party.[125] When Britain and France went to war in 1793, the U.S. needed to determine which side to support.[126] While the differences between the Democratic–Republicans and the Federalists had previously centered on economic matters, foreign policy became an increasingly important issue, as Madison and Jefferson favored France and Hamilton favored Britain.[127] War with Britain became imminent in 1794 after the British seized hundreds of American ships that were trading with French colonies. Madison believed that a trade war with Britain would probably succeed, and would allow Americans to assert their independence fully. The British West Indies, Madison maintained, could not live without American foodstuffs, but Americans could easily do without British manufacturers.[128] Washington then secured friendly trade relations with Britain through the Jay Treaty of 1794.[129] Madison and his Democratic–Republican allies were outraged by the treaty; the Democratic–Republican Robert R. Livingston wrote to Madison that the treaty "sacrifices every essential interest and prostrates the honor of our country".[130] Madison's strong opposition to the treaty led to a permanent break with Washington, ending their friendship.[129]

Marriage and family

On September 15, 1794, Madison married Dolley Payne Todd, the 26-year-old widow of John Todd, a Quaker farmer who died during a yellow fever epidemic in Philadelphia.[131] Earlier that year, Madison and Dolley Todd had been formally introduced at Madison's request by Aaron Burr. Burr had become friends with her when staying at the same Philadelphia boardinghouse.[132] After an arranged meeting in early 1794, the two quickly became romantically engaged and prepared for a wedding that summer, but Todd suffered recurring illnesses because of her exposure to yellow fever in Philadelphia. They eventually traveled to Harewood in Virginia for their wedding. Only a few close family members attended, and Winchester reverend Alexander Balmain presided.[133] Dolley became a renowned figure in Washington, D.C., and excelled at hosting dinners and other important political occasions.[10] She subsequently helped to establish the modern image of the first lady of the United States as an individual who has a leading role in the social affairs of the nation.[134]

Throughout his life, Madison maintained a close relationship with his father, James Sr. Eventually at age 50, Madison inherited the large plantation of Montpelier and other possessions, including his father's numerous slaves.[135][12] While Madison never had children with Dolley, he adopted her one surviving son, John Payne Todd (known as Payne), after the couple's marriage.[136] Some of his colleagues, such as Monroe and Burr, believed Madison's lack of offspring weighed on his thoughts, though he never spoke of any distress.[137] Meanwhile, oral history has suggested Madison may have fathered a child with his enslaved half-sister, a cook named Coreen, but researchers were unable to gather the DNA evidence needed to determine the validity of the accusation.[138][139]

Adams presidency

Washington chose to retire after serving two terms and, in advance of the 1796 presidential election, Madison helped convince Jefferson to run for the presidency.[125] Despite Madison's efforts, Federalist candidate John Adams defeated Jefferson, taking a narrow majority of the electoral vote.[140] Under the rules of the Electoral College then in place, Jefferson became vice president because he finished with the second-most electoral votes.[141] Madison, meanwhile, had declined to seek re-election to the House, and he returned to Montpelier.[136] On Jefferson's advice, Adams considered appointing Madison to an American delegation charged with ending French attacks on American shipping, but Adams's cabinet members strongly opposed the idea.[142]

Though he was out of office, Madison remained a prominent Democratic–Republican leader in opposition to the Adams administration.[143][144] Madison and Jefferson believed that the Federalists were using the Quasi-War with France to justify the violation of constitutional rights by passing the Alien and Sedition Acts, and they increasingly came to view Adams as a monarchist.[145] Both Madison and Jefferson, as leaders of the Democratic–Republican Party, expressed the belief that natural rights were non-negotiable even during a time of war. Madison believed that the Alien and Sedition Acts formed a dangerous precedent, by giving the government the power to look past the natural rights of its people in the name of national security.[146][147] In response to the Alien and Sedition Acts, Jefferson argued that the states had the power to nullify federal law on the basis of the Constitution was a compact among the states. Madison rejected this view of nullification and urged that states respond to unjust federal laws through interposition, a process by which a state legislature declared a law to be unconstitutional but did not take steps to actively prevent its enforcement. Jefferson's doctrine of nullification was widely rejected, and the incident damaged the Democratic–Republican Party as attention was shifted from the Alien and Sedition Acts to the unpopular nullification doctrine.[148]

In 1799, Madison was elected to the Virginia legislature. At the same time, Madison planned for Jefferson's campaign in the 1800 presidential election.[149] Madison issued the Report of 1800, which attacked the Alien and Sedition Acts as unconstitutional. That report held that Congress was limited to legislating on its enumerated powers and that punishment for sedition violated freedom of speech and freedom of the press. Jefferson embraced the report, and it became the unofficial Democratic–Republican platform for the 1800 election.[150] With the Federalists divided between supporters of Hamilton and Adams, and with news of the end of the Quasi-War not reaching the United States until after the election, Jefferson and his running mate, Aaron Burr, defeated Adams, allowing Jefferson to prevail as president.[151][152]

Secretary of State (1801–1809)

Madison was one of two major influences in Jefferson's Cabinet, the other being Secretary of the Treasury Albert Gallatin. Madison was appointed secretary of state despite lacking foreign policy experience.[153][154] An introspective individual, he received assistance from his wife,[134] relying deeply on her in dealing with the social pressures of being a public figure both in his own Cabinet appointment as secretary of state and afterward.[10] As the ascent of Napoleon in France had dulled Democratic–Republican enthusiasm for the French cause, Madison sought a neutral position in the ongoing Coalition Wars between France and Britain.[155] Domestically, the Jefferson administration and the Democratic–Republican Congress rolled back many Federalist policies; Congress quickly repealed the Alien and Sedition Act, abolished internal taxes, and reduced the size of the army and navy.[156] Gallatin, however, did convince Jefferson to retain the First Bank of the United States.[157] Though the Federalist political power was rapidly fading away at the national level, Chief Justice John Marshall ensured that Federalist ideology retained an important presence in the judiciary. In the case of Marbury v. Madison, Marshall simultaneously ruled that Madison had unjustly refused to deliver federal commissions to individuals who had been appointed by the previous administration, but that the Supreme Court did not have jurisdiction over the case. Most importantly, Marshall's opinion established the principle of judicial review.[158] While attaining the position of secretary of state and throughout his life, Madison maintained contact with his father, James Sr., who died in 1801 and which allowed Madison to inherit the large plantation of Montpelier.[135]

Jefferson took office and was sympathetic to the westward expansion of Americans who had settled as far west as the Mississippi River; his sympathy for expansion was supported by his concern for the sparse regional demographics in the far west compared to the more populated eastern states, the far west being inhabited almost exclusively by Native Americans. Jefferson promoted such western expansion and hoped to acquire the Spanish territory of Louisiana, west of the Mississippi River, for expansionist purposes.[159] Early in Jefferson's presidency, the administration learned that Spain planned to retrocede the Louisiana territory to France, raising fears of French encroachment on U.S. territory.[160] In 1802, Jefferson and Madison sent Monroe, a sympathetic fellow Virginian, to France to negotiate the purchase of New Orleans, which controlled access to the Mississippi River and thus was immensely important to the farmers of the American frontier. Rather than merely selling New Orleans, Napoleon's government, having already given up on plans to establish a new French empire in the Americas, offered to sell the entire territory of Louisiana. Despite lacking explicit authorization from Jefferson, Monroe, along with Livingston, whom Jefferson had appointed as America's minister to France, negotiated the Louisiana Purchase, in which France sold more than 827,987 square miles (2,144,480 square kilometers) of land in exchange for $15 million (equivalent to $271,433,333.33 in 2021). [161]

Despite the time-sensitive nature of negotiations with the French, Jefferson was concerned about the constitutionality of the Louisiana Purchase, and he privately favored introducing a constitutional amendment explicitly authorizing Congress to acquire new territories. Madison convinced Jefferson to refrain from proposing the amendment, and the administration ultimately submitted the Louisiana Purchase Treaty for approval by the Senate, without an accompanying constitutional amendment.[162] Unlike Jefferson, Madison was not seriously concerned with the constitutionality of the purchase. He believed that the circumstances did not warrant a strict interpretation of the Constitution, because the expansion was in the country's best interest.[163] The Senate quickly ratified the treaty, and the House, with equal alacrity, passed enabling legislation.[164][165][166]

Early in his tenure, Jefferson was able to maintain cordial relations with both France and Britain, but relations with Britain deteriorated after 1805.[167] The British ended their policy of tolerance towards American shipping and began seizing American goods headed for French ports.[168] They also impressed American sailors, some of whom had originally defected from the British navy, but some of whom had never been British subjects.[169] In response to the attacks, Congress passed the Non-importation Act, which restricted many, but not all, British imports.[168] Tensions with Britain were heightened due to the Chesapeake–Leopard affair, a June 1807 naval confrontation between American and British naval forces, while the French also began attacking American shipping.[170] Madison believed that economic pressure could force the British to end their seizure of American shipped goods, and he and Jefferson convinced Congress to pass the Embargo Act of 1807, which banned all exports to foreign nations.[171] The embargo proved ineffective, unpopular, and difficult to enforce, especially in New England.[172] In March 1809, Congress replaced the embargo with the Non-Intercourse Act, which allowed trade with nations other than Britain and France.[173]

1808 presidential election

Speculation regarding Madison's potential succession to Jefferson commenced early in Jefferson's first term. Madison's status in the party was damaged by his association with the embargo, which was unpopular throughout the country and especially in the Northeast.[174] With the Federalists collapsing as a national party after 1800, the chief opposition to Madison's candidacy came from other members of the Democratic–Republican Party.[175] Madison became the target of attacks from Congressman John Randolph, a leader of a faction of the party known as the tertium quids.[176]

Randolph recruited Monroe, who had felt betrayed by the administration's rejection of the proposed Monroe–Pinkney Treaty with Britain, to challenge Madison for leadership of the party.[177] Many Northerners, meanwhile, hoped that Vice President Clinton could unseat Madison as Jefferson's successor.[178] Despite this opposition, Madison won his party's presidential nomination at the January 1808 congressional nominating caucus.[179] The Federalist Party mustered little strength outside New England, and Madison easily defeated Federalist candidate Charles Cotesworth Pinckney in the general election.[180]

Presidency (1809–1817)

Inauguration and cabinet

Madison's inauguration took place on March 4, 1809, in the House chamber of the U.S. Capitol. Chief Justice Marshall administered the presidential oath of office to Madison while outgoing President Jefferson watched from a seat close by.[181] Vice President George Clinton was sworn in for a second term, making him the first U.S. vice president to serve under two presidents. Unlike Jefferson, who enjoyed relatively unified support, Madison faced political opposition from previous political allies such as Monroe and Clinton. Additionally, the Federalist Party was resurgent owing to opposition to the embargo. Aside from his planned nomination of Gallatin for secretary of state, the remaining members of Madison's Cabinet were chosen merely to further political harmony, and, according to historians Ketcham and Rutland, were largely unremarkable or incompetent.[182][183] Due to the opposition of Monroe and Clinton, Madison immediately faced opposition to his planned nomination of Secretary of the Treasury Gallatin as secretary of state. Madison eventually chose not to nominate Gallatin, keeping him in the treasury department.[184]

Madison settled instead for Robert Smith, the brother of Maryland Senator Samuel Smith, to be the secretary of state.[183] However, for the next two years, Madison performed most of the job of the secretary of state due to Smith's incompetence. After bitter intra-party contention, Madison finally replaced Smith with Monroe in April 1811.[185][186] With a Cabinet full of those he distrusted, Madison rarely called Cabinet meetings and instead frequently consulted with Gallatin alone.[187] Early in his presidency, Madison sought to continue Jefferson's policies of low taxes and a reduction of the national debt.[188] In 1811, Congress allowed the charter of the First Bank of the United States to lapse after Madison declined to take a strong stance on the issue.[189]

War of 1812

Prelude to war

Congress had repealed the Embargo Act of 1807 shortly before Madison became president, but troubles with the British and French continued.[190] Madison settled on a new strategy that was designed to pit the British and French against each other, offering to trade with whichever country would end their attacks against American shipping. The gambit almost succeeded, but negotiations with the British collapsed in mid-1809.[191] Seeking to drive a wedge between the Americans and the British, Napoleon offered to end French attacks on American shipping so long as the United States punished any countries that did not similarly end restrictions on trade.[192] Madison accepted Napoleon's proposal in the hope that it would convince the British to finally end their policy of commercial warfare. Notwithstanding, the British refused to change their policies, and the French reneged on their promise and continued to attack American shipping.[193]

With sanctions and other policies having failed, Madison determined that war with Britain was the only remaining option.[194] Many Americans called for a "second war of independence" to restore honor and stature to their new nation, and an angry public elected a "war hawk" Congress, led by Henry Clay and John C. Calhoun.[195] With Britain already engaged in the Napoleonic Wars, many Americans including Madison believed that the United States could easily capture Canada, using it as a bargaining chip for other disputes or simply retaining control of it.[196] On June 1, 1812, Madison asked Congress for a declaration of war, stating that the United States could no longer tolerate Britain's "state of war against the United States". The declaration of war was passed along sectional and party lines, with opposition to the declaration coming from Federalists and from some Democratic–Republicans in the Northeast.[197] In the years prior to the war, Jefferson and Madison had reduced the size of the military, leaving the country with a military force consisting mostly of poorly trained militia members.[198] Madison asked Congress to quickly put the country "into an armor and an attitude demanded by the crisis", specifically recommending expansion of the army and navy.[199]

Military actions

Given the circumstances involving Napoleon in Europe, Madison initially believed the war would result in a quick American victory.[196][200] Madison ordered three landed military spearhead incursions into Canada, starting from Fort Detroit, designed to loosen British control around American-held Fort Niagara and destroy the British supply lines from Montreal. These actions would gain leverage for concessions to protect American shipping in the Atlantic.[200] Without a standing army, Madison counted on regular state militias to rally to the flag and invade Canada: still, governors in the Northeast failed to cooperate.[201] The British army was more organized, used professional soldiers, and fostered an alliance with Native American tribes led by Tecumseh. On August 16, during the British siege of Detroit, Major General William Hull panicked, after the British fired on the fort, killing two American officers. Terrified of an Indian attack, drinking heavily, Hull quickly ordered a white tablecloth out a window and unconditionally surrendered Fort Detroit and his entire army to British Major-General Sir Issac Brock.[200][202] Hull was court-martialed for cowardice, but Madison intervened and saved him from being shot.[202] On October 13, a separate force from the United States was defeated at Queenston Heights, although Brock was killed.[203][200] Commanding General Henry Dearborn, hampered by mutinous New England infantry, retreated to winter quarters near Albany, failing to destroy Montreal's vulnerable British supply lines.[200] Lacking adequate revenue to fund the war, the Madison administration was forced to rely on high-interest loans furnished by bankers based in New York City and Philadelphia.[204]

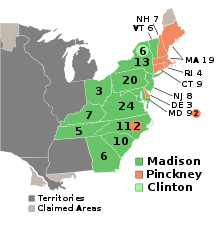

In the 1812 presidential election, held during the early stages of the war, Madison was re-nominated without opposition.[205] A dissident group of New York Democratic-Republicans nominated DeWitt Clinton, the lieutenant governor of New York and a nephew of recently deceased Vice President George Clinton, to oppose Madison in the 1812 election. This faction of Democratic-Republicans hoped to unseat the president by forging a coalition among Democratic-Republicans opposed to the coming war, as well as those party faithful angry with Madison for not moving more decisively toward war, northerners weary of the Virginia dynasty and southern control of the White House, and many New Englanders wanted Madison replaced. Dismayed about their prospects of beating Madison, a group of top Federalists met with Clinton's supporters to discuss a unification strategy. Difficult as it was for them to join forces, they nominated Clinton for President and Jared Ingersoll, a Philadelphia lawyer, for vice president.[48] Hoping to shore up his support in the Northeast, where the War of 1812 was unpopular, Madison selected Governor Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts as his running mate,[206] though Gerry would only survive two years after the election due to advanced old age.[207] Despite the maneuverings of Clinton and the Federalists, Madison won re-election, though by the narrowest margin of any election since that of 1800 in the popular vote as later supported by the electoral vote as well. He received 128 electoral votes to 89 for Clinton.[208] With Clinton winning most of the Northeast, Madison won Pennsylvania in addition to having swept the South and the West which ensured his victory.[209][210]

After the disastrous start to the war, Madison accepted Russia's invitation to arbitrate and sent a delegation led by Gallatin and John Quincy Adams (the first son of former President John Adams) to Europe to negotiate a peace treaty.[196] While Madison worked to end the war, the United States experienced some impressive naval successes, by the USS Constitution and other warships, that boosted American morale.[211][200] Victorious in the Battle of Lake Erie, the U.S. crippled the supply and reinforcement of British military forces in the western theater of the war.[212] In the aftermath of the Battle of Lake Erie, General William Henry Harrison defeated the forces of the British and of Tecumseh's confederacy at the Battle of the Thames. The death of Tecumseh in that battle marked the permanent end of armed Native American resistance in the Old Northwest and any hope of a united Indian nation.[213] In March 1814, Major General Andrew Jackson broke the resistance of the British-allied Muscogee Creek in the Old Southwest with his victory at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend.[214] Despite those successes, the British continued to repel American attempts to invade Canada, and a British force captured Fort Niagara and burned the American city of Buffalo in late 1813.[215]

On August 24, 1814, the British landed a large force on the shores of Chesapeake Bay and routed General William Winder's army at the Battle of Bladensburg.[216] Madison, who had earlier inspected Winder's army,[217] escaped British capture by fleeing to Virginia on a fresh horse, though the British captured Washington and burned many of its buildings, including the White House.[218][219] Escaping capture by the British, Dolley had abandoned the capital and fled to Virginia, but only after securing the portrait of George Washington.[217] The charred remains of the capital signified a humiliating defeat for James Madison and America.[220] On August 27, Madison returned to Washington to view the carnage of the city.[220] Dolley returned the next day, and on September 8, the Madisons moved into the Octagon House. The British army next advanced on Baltimore, but the U.S. repelled the British attack in the Battle of Baltimore, and the British army departed from the Chesapeake region in September.[221] That same month, U.S. forces repelled a British invasion from Canada with a victory at the Battle of Plattsburgh.[222] The British public began to turn against the war in North America, and British leaders began to look for a quick exit from the conflict.[223]

In January 1815, Jackson's troops defeated the British at the Battle of New Orleans.[224] Just more than a month later, Madison learned that his negotiators led by John Quincy Adams had concluded the Treaty of Ghent on December 24, 1814, which ended the war.[225]

Madison quickly sent the treaty to the Senate, which ratified it on February 16, 1815.[226] Although the overall result of the war ended in a standoff, the quick succession of events at the end of the war, including the burning of the capital, the Battle of New Orleans, and the Treaty of Ghent, made it appear as though American valor at New Orleans had forced the British to surrender. This view, while inaccurate, strongly contributed to bolstering Madison's reputation as president. Native Americans lost the most, including their land and independence.[227] Napoleon's defeat at the June 1815 Battle of Waterloo brought a final close to the Napoleonic Wars and thus an end to the hostile seizure of American shipping by British and French forces.[228]

Postwar period and decline of the Federalist opposition

The postwar period of Madison's second term saw the transition into the "Era of Good Feelings" between mid-1815 and 1817, with the Federalists experiencing a further decline in influence.[229] During the war, delegates from the New England states held the Hartford Convention, where they asked for several amendments to the Constitution.[230] Though the Hartford Convention did not explicitly call for the secession of New England,[231] the Convention became an adverse political millstone around the Federalist Party as general American sentiment had moved towards a celebrated unity among the states in what they saw as a successful "second war of independence" from Britain.[232]

Madison hastened the decline of the Federalists by adopting several programs he had previously opposed.[233] Recognizing the difficulties of financing the war and the necessity of an institution to regulate American currency, Madison proposed the re-establishment of a national bank. He also called for increased spending on the army and the navy, a tariff designed to protect American goods from foreign competition, and a constitutional amendment authorizing the federal government to fund the construction of internal improvements such as roads and canals. Madison's initiatives to now act on behalf of a national bank appeared to reverse his earlier opposition to Hamilton and were opposed by strict constructionists such as John Randolph, who stated that Madison's proposals now "out-Hamiltons Alexander Hamilton".[234] Responding to Madison's proposals, the 14th Congress compiled one of the most productive legislative records up to that point in history.[235] Congress granted the Second Bank of the United States a twenty-five-year charter[234] and passed the Tariff of 1816, which set high import duties for all goods that were produced outside the United States.[235] Madison approved federal spending on the Cumberland Road, which provided a link to the country's western lands;[236] still, in his last act before leaving office, he blocked further federal spending on internal improvements by vetoing the Bonus Bill of 1817 arguing that it unduly exceeded the limits of the General Welfare Clause concerning such improvements.[237]

Native American policy

Upon becoming president, Madison said the federal government's duty was to convert Native Americans by the "participation of the improvements of which the human mind and manners are susceptible in a civilized state".[188] In 1809, General Harrison began to push for a treaty to open more land for white American settlement. The Miami, Wea, and Kickapoo were vehemently opposed to selling any more land around the Wabash River.[238] To motivate those groups to sell their land, Harrison decided, against the wishes of Madison, to first conclude a treaty with the tribes who were willing to sell and use those treaties to help influence those who held out. In September 1809, Harrison invited the Potawatomie, Delaware, Eel Rivers, and the Miami to a meeting in Fort Wayne. During the negotiations, Harrison promised large subsidies and direct payments to the tribes if they would cede the other lands under discussion.[239] On September 30, 1809, little more than six months into his first term, Madison agreed to the Treaty of Fort Wayne, negotiated and signed by Indiana Territory's Governor Harrison.[240] In the treaty, the American Indian tribes were compensated $5,200 (equivalent to $90,092.77 in 2021) in goods and $500 in cash (equivalent to $8,662.77 in 2021), with $250 in annual payments (equivalent to $4,331.38 in 2021), in return for the cession of 3 million acres of land (approximately 12,140 square kilometers) with incentivized subsidies paid to individual tribes for exerting their influence over less cooperative tribes.[241][242] The treaty angered Shawnee leader Tecumseh, who said, "Sell a country! Why not sell the air, the clouds and the great sea, as well as the earth?"[243] Harrison responded that tribes were the owners of their land and could sell it to whomever they wished.[244]

Like Jefferson, Madison had a paternalistic attitude toward American Indians, encouraging them to become farmers.[245] Madison believed the adoption of European-style agriculture would help Native Americans assimilate the values of British–U.S. civilization. As pioneers and settlers moved West into large tracts of Cherokee, Choctaw, Creek, and Chickasaw territory, Madison ordered the U.S. Army to protect Native lands from intrusion by settlers. This was done to the chagrin of his military commander Andrew Jackson, who wanted Madison to ignore Indian pleas to stop the invasion of their lands.[246] Tensions continued to mount between the United States and Tecumseh over the 1809 Treaty of Fort Wayne, which ultimately led to Tecumseh's alliance with the British and the Battle of Tippecanoe, on November 7, 1811, in the Northwest Territory.[246][247] The divisions among the Native American leaders were bitter and before leaving the discussions, Tecumseh informed Harrison that unless the terms of the negotiated treaty were largely nullified, he would seek an alliance with the British.[248]

The situation continued to escalate, eventually leading to the outbreak of hostilities between Tecumseh's followers and American settlers later that year. Tensions continued to rise, leading to the Battle of Tippecanoe during a period sometimes called Tecumseh's War.[249][250] Tecumseh was defeated and Indians were pushed off their tribal lands, replaced entirely by white settlers.[246][247] In addition to the Battle of the Thames and the Battle of Horseshoe Bend, other wars with American Indians took place, including the Peoria War, and the Creek War. Negotiated by Jackson, in the aftermath of the Creek War, the Treaty of Fort Jackson of August 9, 1814, added approximately 23 million acres of land to the United States (93,000 square kilometers) in Georgia and Alabama.[251][252] Privately, Madison did not believe American Indians could be fully assimilated to the values of Euro-American culture. He believed that Native Americans may have been unwilling to make "the transition from the hunter, or even the herdsman state, to the agriculture". Madison feared that Native Americans had too great an influence on the settlers they interacted with, who in his view was "irresistibly attracted by that complete liberty, that freedom from bonds, obligations, duties, that absence of care and anxiety which characterize the savage state". Later in Madison's term, in March 1816, Madison's Secretary of War William Crawford advocated for the government to encourage intermarriages between Native Americans and whites as a way of assimilating the former. This prompted public outrage and exacerbated anti-indigenous bigotry among white Americans, as seen in hostile letters sent to Madison, who remained publicly silent on the issue.[243]

Election of 1816

In the 1816 presidential election, Madison and Jefferson both favored the candidacy of Secretary of State James Monroe, who defeated Secretary of War William H. Crawford in the party's congressional nominating caucus. As the Federalist Party continued to collapse, Monroe easily defeated Federalist candidate, New York Senator Rufus King, in the 1816 election.[253] Madison left office as a popular president; former president Adams wrote that Madison had "acquired more glory, and established more union, than all his three predecessors, Washington, Adams, and Jefferson, put together".[254]

Post-presidency (1817–1836)

When Madison left office in 1817 at age 65, he retired to Montpelier, not far from Jefferson's Monticello. As with both Washington and Jefferson, Madison left the presidency a poorer man than when he came in. His plantation experienced a steady financial collapse, due to price declines in tobacco and his stepson's mismanagement.[10] In his retirement, Madison occasionally became involved in public affairs, advising Andrew Jackson and other presidents.[255] He remained out of the public debate over the Missouri Compromise, though he privately complained about the North's opposition to the extension of slavery.[256] Madison had warm relations with all four of the major candidates in the 1824 presidential election, but, like Jefferson, largely stayed out of the race.[257] During Jackson's presidency, Madison publicly disavowed the Nullification movement and argued that no state had the right to secede.[258] Madison also helped Jefferson establish the University of Virginia.[259] In 1826, after the death of Jefferson, Madison was appointed as the second rector of the university. He retained the position as college chancellor for ten years until his death in 1836.[260]

In 1829, at the age of 78, Madison was chosen as a representative to the Virginia Constitutional Convention for revision of the commonwealth's constitution. It was his last appearance as a statesman. Apportionment of adequate representation was the central issue at the convention for the western districts of Virginia. The increased population in the Piedmont and western parts of the state were not proportionately represented in the legislature. Western reformers also wanted to extend suffrage to all white men, in place of the prevailing property ownership requirement. Madison made modest gains but was disappointed at the failure of Virginians to extend suffrage to all white men.[261]

In his later years, Madison became highly concerned about his historical legacy. He resorted to modifying letters and other documents in his possession, changing days and dates, and adding and deleting words and sentences. By his late seventies, Madison's self-editing of his own archived letters and older materials had become almost an obsession. As an example, he edited a letter written to Jefferson criticizing Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette; Madison not only inked out original passages but in other correspondence he even forged Jefferson's handwriting.[262] Historian Drew R. McCoy wrote that "During the final six years of his life, amid a sea of personal [financial] troubles that were threatening to engulf him ... At times mental agitation issued in physical collapse. For the better part of a year in 1831 and 1832 he was bedridden, if not silenced ... Literally sick with anxiety, he began to despair of his ability to make himself understood by his fellow citizens."[263]

Death

Madison's health slowly deteriorated through the early-to-mid-1830s.[264] Approaching the Fourth of July, he died of congestive heart failure at Montpelier on the morning of June 28, 1836, at the age of 85.[265] According to one common account of his final moments, he was given his breakfast, which he tried eating but was unable to swallow. His favorite niece,[clarification needed] who sat by to keep him company, asked him, "What is the matter, Uncle James?" Madison died immediately after he replied, "Nothing more than a change of mind, my dear."[266] He was buried in the family cemetery at Montpelier.[10] He was one of the last prominent members of the Revolutionary War generation to die.[255] His last will and testament left significant sums to the American Colonization Society, Princeton, and the University of Virginia, as well as $30,000 ($897,000 in 2021) to his wife, Dolley. Left with a smaller sum than James had intended, Dolley suffered financial troubles until her death in 1849.[267] In the 1840s Dolley sold Montpelier, its remaining slaves, and the furnishings to pay off outstanding debts. Paul Jennings, one of Madison's younger slaves, later recalled in his memoir,

In the last days of her life, before Congress purchased her husband's papers, she was in a state of absolute poverty, and I think sometimes suffered for the necessaries of life. While I was a servant to Mr. Webster, he often sent me to her with a market-basket full of provisions, and told me whenever I saw anything in the house that I thought she was in need of, to take it to her. I often did this, and occasionally gave her small sums from my own pocket, though I had years before bought my freedom of her.[268]

Political and religious views

| Part of the Politics series |

| Republicanism |

|---|

|

|

Federalism

| External videos | |

|---|---|

During his first stint in Congress in the 1780s, Madison came to favor amending the Articles of Confederation to provide for a stronger central government.[269] In the 1790s, he led the opposition to Hamilton's centralizing policies and the Alien and Sedition Acts.[270] Madison's support of the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions in the 1790s has been referred to as "a breathtaking evolution for a man who had pleaded at the Constitutional Convention that the federal government should possess a veto over state laws".[87]

Others historians disagree, and see Madison's political philosophy as remarkably consistent. And, perhaps more importantly, they point out that Madison's loyalty was to the Constitution, not to his personal preferences. Madison had advocated in the debates of the Constitutional Convention that the proposed federal government have veto power over state laws, but he was willing to follow the Constitution as it was adopted and ratified, rather than what he might have wished that it said. Madison, who was one of the principal authors of the Federalist Papers, had written in Federalist #45 that the proposed federal government would have powers that were "few and defined" (as enumerated in Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution). He felt strongly that to interpret it otherwise would be a breach of faith with "We the People" who had ratified the Constitution based on that understanding.[271][272][273][274][275][276]

Madison, who was the author of the Bill of Rights, was also faithfully following the 10th Amendment, which says that all "powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people."[277][278][279][280]

Religion

Although baptized as an Anglican and educated by Presbyterian clergymen,[281] young Madison was an avid reader of English deist tracts.[282] As an adult, Madison paid little attention to religious matters. Though most historians have found little indication of his religious leanings after he left college,[283] some scholars indicate he leaned toward deism.[284][285] Others maintain that Madison accepted Christian tenets and formed his outlook on life with a Christian worldview.[286] Regardless of his own religious beliefs, Madison believed in religious liberty, and he advocated for Virginia's disestablishment of religious institutions sponsored by the state.[287] He also opposed the appointments of chaplains for Congress and the armed forces, arguing that the appointments produce religious exclusion as well as political disharmony.[288][289]

Slavery

Throughout his life, Madison's views on slavery were conflicted. He was born into a plantation society that relied on slave labor, and both sides of his family profited from tobacco farming.[290] While he viewed slavery as essential to the Southern economy, he was troubled by the instability of a society that depended on a large slave population.[291] Madison also believed slavery was incompatible with American Revolutionary principles, though he owned over one hundred African American slaves.[290]

History

Madison grew up on Montpelier, his family's plantation in Virginia. Like other southern plantations, Montpelier depended on slave labor. When Madison left for college on August 10, 1769, he arrived at Princeton accompanied by his slave Sawney, who was charged with Madison's expenses and with relaying messages to his family back home.[290] In 1783, fearing the possibility of a slave rebellion at Montpelier, Madison emancipated one slave, Billey, selling him into a seven-year apprentice contract. After his manumission, Billey changed his name to William Gardner, married and had a family,[292] and became a shipping agent, representing Madison in Philadelphia. In 1795, Gardner was swept overboard and drowned on a voyage to New Orleans. [293] [294] Madison inherited Montpelier and its more than one hundred slaves, after his father's death in 1801.[295] That same year, Madison was appointed Secretary of State by President Jefferson, and he moved to Washington D.C., running Montpelier from afar making no effort to free his slaves. After his election to the presidency in 1808, Madison brought his slaves to the White House.[290] During the 1820s and 1830s, Madison sold some of his land and slaves to repay debt. In 1836, at the time of Madison's death, he owned 36 taxable slaves.[296] In his will, Madison gave his remaining slaves to his wife Dolley and charged her not to sell the slaves without their permission. For reasons of necessity, Dolley did not comply and sold the slaves without their permission to pay off debts.[290]

Treatment of slaves

As was consistent with the "established social norms of Virginia society",[297] Madison was known from his farm papers for advocating the humane treatment of his slaves at Montpelier. He instructed an overseer to "treat the Negroes with all the humanity and kindness consistent with their necessary subordination and work."[298] Madison also ensured that his slaves had milk cows and meals for their daily food.[299] By the 1790s, Madison's slave Sawney was an overseer of part of the plantation. Madison ordered Sawney by letter to ready fields for growing apples, corn, tobacco, and Irish potatoes. Like Sawney, some slaves at Montpelier could read.[299] Enslaved people at Montpelier worked six days a week from dawn to dusk, with a mid-day break, and got Sundays off.[300][301] Paul Jennings was a slave of the Madisons for 48 years. Jennings, born into slavery in 1799 at the Montpelier plantation, served as Madison's footman at the White House. In his memoir A Colored Man's Reminiscences of James Madison, published in 1865, Jennings said that he "never knew [Madison] to strike a slave, although he had over one hundred; neither would he allow an overseer to do it." As a house slave, Jennings had a basic education and was literate, taught in mathematics, and played the violin. Although Jennings condemned slavery, he said that James was "one of the best men that ever lived", and that Dolley was "a remarkably fine woman."[302][303]

Views on slavery

Madison called slavery "the most oppressive dominion" that ever existed,[304] and he had a "lifelong abhorrence" for it.[305] In 1785 Madison spoke in the Virginia Assembly favoring a bill that Thomas Jefferson had proposed for the gradual abolition of slavery, and he also helped defeat a bill designed to outlaw the manumission of individual slaves.[305] As a slaveholder, Madison was aware that owning slaves was not consistent with revolutionary values,[306] but, as a pragmatist, this sort of self-contradiction was a common feature in his political career.[307] Historian Drew R. McCoy said that Madison's antislavery principles were indeed "impeccable."[308] Historian Ralph Ketcham said, "[a]lthough Madison abhorred slavery, he nonetheless bore the burden of depending all his life on a slave system that he could never square with his republican beliefs."[7] There is no evidence Madison thought black people were inferior.[309][304] Madison believed blacks and whites were unlikely to co-exist peacefully due to "the prejudices of the whites" as well as feelings on both sides "inspired by their former relation as oppressors and oppressed."[310] As such, he became interested in the idea of freedmen establishing colonies in Africa and later served as the president of the American Colonization Society, which relocated former slaves to Liberia.[311] Madison believed that this solution offered a gradual, long-term, but potentially feasible means of eradicating slavery in the United States.[312] Madison nevertheless thought that peaceful co-existence between the two racial groups could eventually be achieved in the long run.[298]

Madison initially opposed the Constitution's 20-year protection of the foreign slave trade, but he eventually accepted it as a necessary compromise to get the South to ratify the document.[313] He also proposed that apportionment in the House of Representatives be according to each state's free and enslaved population, eventually leading to the adoption of the Three-fifths Compromise.[314] Madison supported the extension of slavery into the West during the Missouri crisis of 1819–1821,[315] asserting that the spread of slavery would not lead to more slaves, but rather diminish their generative increase through dispersing them,[h] thus substantially improving their condition, accelerating emancipation, easing racial tensions, and increasing "partial manumissions."[317] Madison thought of slaves as "wayward (but still educable) students in need of regular guidance."[298] According to historian Paris Spies-Gans, Madison's anti-slavery thought was strongest "at the height of Revolutionary politics. But by the early 1800s, when in a position to truly impact policy, he failed to follow through on these views." Spies-Gans concluded, "[u]ltimately, Madison's personal dependence on slavery led him to question his own, once enlightened, definition of liberty itself."[290]

Legacy

Historical reputation

Regarded as one of the Founding Fathers of the United States, Madison had a wide influence on the founding of the nation and upon the early development of American constitutional government and foreign policy. Historian J.C.A. Stagg writes that "in some ways—because he was on the winning side of every important issue facing the young nation from 1776 to 1816—Madison was the most successful and possibly the most influential of all the Founding Fathers."[48] Though he helped found a major political party and served as the fourth president, his legacy has largely been defined by his contributions to the Constitution; even in his own life he was hailed as the "Father of the Constitution".[318] Law professor Noah Feldman writes that Madison "invented and theorized the modern ideal of an expanded, federal constitution that combines local self-government with an overarching national order".[319] Feldman adds that Madison's "model of liberty-protecting constitutional government" is "the most influential American idea in global political history".[319][i] Various rankings of historians and political scientists tend to rank Madison as an above average president with a 2018 poll of the American Political Science Association's Presidents and Executive Politics section ranking Madison as the twelfth best president.[315]

Various historians have criticized Madison's tenure as president.[321] In 1968, Henry Steele Commager and Richard B. Morris said the conventional view of Madison was of an "incapable President" who "mismanaged an unnecessary war".[322] A 2006 poll of historians ranked Madison's failure to prevent the War of 1812 as the sixth-worst mistake made by a sitting president.[323] Regarding Madison's consistency and adaptability of policy-making during his many years of political activity, historian Gordon S. Wood says that Lance Banning, as in his Sacred Fire of Liberty (1995), is the "only present-day scholar to maintain that Madison did not change his views in the 1790s".[324]

During and after the War of 1812, Madison came to support several of the policies that he opposed in the 1790s, including the national bank, a strong navy, and direct taxes.[325] Wood notes that many historians struggle to understand Madison, but Wood looks at him in the terms of Madison's own times—as a nationalist but one with a different conception of nationalism than that of the Federalists.[324] Gary Rosen uses other approaches to suggest Madison's consistency.[326] Historian Garry Wills wrote, "Madison's claim on our admiration does not rest on a perfect consistency, any more than it rests on his presidency. He has other virtues. ... As a framer and defender of the Constitution he had no peer. ... No man could do everything for the country—not even Washington. Madison did more than most, and did some things better than any. That was quite enough."[327]

Popular culture

Madison, portrayed by Burgess Meredith, is a key protagonist in the 1946 Hollywood film Magnificent Doll, which focuses on a fictionalized account of Dolley Madison's romantic life.[328] Madison is also portrayed in the popular musical Hamilton, played by Joshua Henry in the original 2013 Vassar version and then revised by Okieriete Onaodowan for the 2015 Broadway opening.[329][330][331] In the Broadway musical, Madison, joined by Jefferson and Burr, confront Hamilton about his affaire de cœur in the Reynolds affair by intoning the rap lyrics to the song "We Know". Onaodowan won a Grammy Award for his portrayal of Madison.[332]

Memorials