Aylesford

| Aylesford | |

|---|---|

Medieval bridge over the River Medway at Aylesford | |

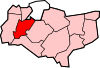

Location within Kent | |

| Population | 10,660 (2011)[1] |

| OS grid reference | TQ729589 |

| District | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | AYLESFORD |

| Postcode district | ME20 |

| Dialling code | 01622 |

| Police | Kent |

| Fire | Kent |

| Ambulance | South East Coast |

| UK Parliament | |

Aylesford is a village and civil parish on the River Medway in Kent, England, 4 miles (6 km) northwest of Maidstone.

Originally a small riverside settlement, the old village comprises around 60 houses, many of which were formerly shops. Two pubs, a village shop and other amenities are located on the high street. Aylesford's current population is around 5,000.[2][citation needed]

The Parish of Aylesford covers more than seven square miles (18 km2), stretching north to Rochester Airport estate and south to Barming,[3] and has a total population of over 10,000 (as of 2011),[4] with the main settlements at Aylesford, Eccles, Blue Bell Hill and (part of) Walderslade.[5]

Aylesford Newsprint was a long-established major employer in the area and was the largest paper recycling factory in Europe, manufacturing newsprint for the newspaper industry. In 2015, Aylesford Paper Mill, as it was known by local residents, was closed down and stripped of all its assets.[6]

History

[edit]There has been activity in the area since Neolithic times. There are several chamber tombs north of the village, of which Kit's Coty House, 1.5 miles (2.4 km) to the north, is the most famous; all have been damaged by farming. Kit's Coty is the remains of the burial chamber at one end of a long barrow. Just south of this, situated lower down the same hillside, is a similar structure, Little Kits Coty House (also known as the Countless Stones).

Bronze Age swords have been discovered near here and an Iron Age settlement and Roman villa stood at Eccles. A cemetery of the British Iron Age discovered in 1886 was excavated under the leadership of Sir Arthur Evans (of Knossos fame), and published in 1890. Many of Evans' finds are now kept in the British Museum, including a bronze jug, pan and 'bucket' with handles in the form of a human face from a cremation burial.[7] With the later excavation at Swarling not far away (discovery to publication was 1921–1925) this is the type site for Aylesford-Swarling pottery or the Aylesford-Swarling culture. Evan's conclusion that the site belonged to a culture closely related to the continental Belgae, remains the modern view, though the dating has been refined to the period after about 75 BC.[8] The village has been suggested as the site of the Battle of the Medway during the Roman invasion of Britain although there is no direct evidence of this.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records the Battle of Aylesford taking place nearby in 455, when the Germanic Hengest fought the Welsh Vortigern;[9] Horsa (Hengist's brother) is said to have fallen in this battle; Alfred the Great defeated the Danes in 893; as did Edmund II Ironside in 1016.

Following the Norman Conquest of 1066, the manor of Aylesford was owned by William the Conqueror. Some of the land was given to the Bishop of Rochester as compensation for land seized for the building of Rochester Castle. The Domesday Book of 1086 records: Also the Bishop of Rochester holds as much of this land as is worth 17s6d in exchange for the land on which the castle stands.[10] 17s6d is the rental value (as used for taxation), not the capital value.

The church of St Peter and St Paul is of Norman origin. Here there is a memorial to the Culpeper family, who owned the nearby Preston Hall Estate.

The Friars

[edit]

In 1240, Ralph Frisburn, on his return from the Holy Land, founded a Carmelite monastery under the patronage of Richard, Lord Grey of Codnor, among the first of the Order to be founded in Europe. He was followed later by Simon Stock, who in 1254 was elected Prior General of the now mendicant Carmelites. Saint Simon died in 1265, whilst on a visit to Bordeaux, whereafter, his remains were honoured for centuries. In July 1951, his relics (remains of his head) were installed in a reliquary at the friary.

Following the Dissolution of the Monasteries by Henry VIII in 1536, ownership of the site was transferred in 1538 to Sir Thomas Wyatt of nearby Allington Castle. Following the rebellion against Queen Mary by Sir Thomas's son, Thomas Wyatt the younger, the property was forfeited back to the crown. Possession was later granted to Sir John Sedley by Mary's half-sister Queen Elizabeth.[11] The Sedleys sold the estate to Sir Peter Ricaut and his family. Although the Sedley family made some changes to the priory, it was the next owner, Sir John Banks, in the 1670s, who was responsible for the remodelling of the buildings.[12] In 1696, the estate passed by marriage to Heneage Finch, later created Earl of Aylesford.

The main part of the house was destroyed by fire in the 1930s, revealing many original features, which had been hidden by Banks's alterations. The Carmelites purchased it in 1949 from the Hewitt family and restored some of the original buildings; beyond the cloisters four chapels have been built to service the needs of the many different groups that visit yearly (The Choir Chapel - where the community celebrates daily Mass and the Liturgy of the Hours; St Joseph's; St Anne's; and the Relic Chapel, which houses the remains of St Simon Stock). Aesthetically, the modern build shows sensitivity to the existing buildings with a mixture of English Gothic (perpendicular Gothic) and Tudor features; many modern materials have been employed but traditional peg tiles are on the roofs and are the walls are faced in Kentish ragstone. The priory is a popular place for pilgrimage, as well as for retreats and conferences. The friary has some notable artwork, such as many pieces by the ceramic artist Adam Kossowski. The remains of the manor house present at the foundation of the priory are believed to lie under the Great Courtyard; this could date from as early as 1085.[13]

River Medway

[edit]Due to the village's location on its banks, the River Medway has been a key influence on its development. Aylesford takes its name from an Old English personal name, and literally denotes 'Ægel's ford'. Its first recorded use is from the tenth century, as Æglesforda. It was also the place where one of the earliest bridges across the Medway was built, believed to be in the 14th century (although the wide central span seen today is later). Upstream from Rochester Bridge, it became the next bridging point. The river was navigable as far as Maidstone until 1740, when barges of forty tons could reach as far as Tonbridge. As a result, wharves were built, one being at Aylesford. Corn, fodder and fruit, along with stone and timber, were the principal cargoes. Due to increased road traffic in recent years, the ancient bridge has now been superseded by a modern structure nearby, but remains in use for pedestrians.

The village

[edit]

The oldest parts of the village lie north and immediately south of the Medway. Many of the buildings are of great antiquity: the Chequers Inn, the George House (formerly a coaching inn) and the almshouses among them. St Peter and St Paul's church, parts of which date back to the Norman invasion,[14] sits on a hill in the southern part of the village. Major construction took place during the Victorian era, when houses were built to serve the nearby quarry. The brick and tile industries have been replaced by a large area of commercial buildings, and what was once the huge Aylesford paper mills site was later regenerated by a leading newsprint plant surrounded by newly developed private estates featuring high value accommodation.[citation needed]

Recent expansion has been to the southern side of the river, where a substantial suburban housing estate has grown up, partly because the village is served by the railway, with connections for Maidstone and London. Many of these homes were originally owned by employees of the paper mills, which are now closed and which have been replaced by a number of smaller industrial estates with a variety of specialist businesses that include engineering, manufacturing, wholesale and others.

Schools

[edit]Henry Arthur Brassey (1840–1891) was a great benefactor of Aylesford, and as well as financing major repairs to the church, also provided the village with a school. This was replaced in the 1960s with a new building to the south east of the village, next to the site of the local secondary school (now Aylesford School - Sports College) which was housed in buildings largely built in the 1940s by Italian prisoners of War. The old school buildings were totally rebuilt on the same site in 2008. The original village school – now known as the Brassey Centre – is used as a church office and community hall.

Railway

[edit]Aylesford railway station, opened on 18 June 1856, is on the Medway Valley Line connecting Strood with Maidstone (West) and Paddock Wood. The original station buildings – gabled and highly decorated, built in Kentish ragstone with Caen stone dressings, with windows that replicate those at Aylesford Priory – have been used as a fast food restaurant in recent years following restoration in the 1980s.

Royal British Legion Village

[edit]Located to the south of Aylesford, on the A20 London Road, the Royal British Legion Village was founded after the First World War to help injured soldiers following their discharge from the nearby Preston Hall hospital. It was first the centre of a small farming community known as The Preston Hall Colony. When the British Legion was founded in 1921, it became one of the first branches and, by 1925, was known as Royal British Legion Village. A thriving community has since developed, providing nursing homes, sheltered housing and independent living units, as well as employment and social activities, helping all disabled veterans living in, or moving to, the area.[15] In 1972 the Poppy Appeal headquarters moved to the village, which now forms one of the main centres of Legion life and activities. An industrial complex in the village houses Royal British Legion industries, including the manufacture of road and public signs used throughout the UK.[16]

Sports

[edit]Aylesford Football Club are based in the village, playing at the Recreation Ground on Forstal Road since before the War[citation needed] Aylesford Bulls Rugby Football Club is located at the Jack Williams Memorial Ground in Hall Road. They run children's age-grade teams from U6-U18 plus several adult teams for men and women of all levels.

The village is home to what is claimed to be Britain's oldest operating sauna, the Finnish Sauna Bath. Built for the London Olympics in 1948, it was subsequently moved to Aylesford.[a][18]

Demography

[edit]This section needs to be updated. (January 2023) |

| Aylesford compared | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 UK Census | Aylesford ward | Tonbridge and Malling borough | England |

| Population | 4,548 | 107,561 | 49,138,831 |

| Foreign born | 3.8% | 4.6% | 9.2% |

| White | 98.2% | 98.3% | 90.9% |

| Asian | 0.9% | 0.7% | 4.6% |

| Black | 0.1% | 0.1% | 2.3% |

| Christian | 77.4% | 76.1% | 71.7% |

| Muslim | 0.2% | 0.3% | 3.1% |

| Hindu | 0.5% | 0.2% | 1.1% |

| No religion | 12.8% | 15% | 14.6% |

| Unemployed | 1.9% | 1.9% | 3.3% |

| Retired | 15.3% | 14.2% | 13.5% |

At the 2001 UK census, the Aylesford electoral ward had a population of 4,548. The ethnicity was 98.2% white, 0.8% mixed race, 0.9% Asian, 0.1% black and 0% other. The place of birth of residents was 96.2% United Kingdom, 0.5% Republic of Ireland, 1% other Western European countries, and 2.3% elsewhere. Religion was recorded as 77.4% Christian, 0.2% Buddhist, 0.5% Hindu, 0.1% Sikh, 0% Jewish, and 0.2% Muslim. 12.8% were recorded as having no religion, 0.1% had an alternative religion and 8.8% did not state their religion.[19]

The economic activity of residents aged 16–74 was 41.1% in full-time employment, 14.5% in part-time employment, 9.3% self-employed, 1.9% unemployed, 2.2% students with jobs, 2.5% students without jobs, 15.3% retired, 6.7% looking after home or family, 4.4% permanently sick or disabled and 2.2% economically inactive for other reasons. The industry of employment of residents was 19.6% retail, 13.6% manufacturing, 9.2% construction, 13.2% real estate, 9.7% health and social work, 6.1% education, 8% transport and communications, 4.8% public administration, 3.6% hotels and restaurants, 4.7% finance, 1.1% agriculture and 6.4% other. Compared with national figures, the ward had a relatively high proportion of workers in construction, and a relatively low proportion in agriculture, education, hotels and restaurants. Of the ward's residents aged 16–74, 14.3% had a higher education qualification or the equivalent, compared with 19.9% nationwide.[19]

Lathe of Aylesford

[edit]The Lathe of Aylesford, in the western division of the county of Kent, comprised 13 Hundreds, and was bounded on the north by the river Thames, on the west by the Lathe of Sutton at Hone, on the south by the county of Sussex and on the east by the Lathe of Scray. It was the second in extent, and embraced an area of 233,580 acres (94,530 ha), and had the largest population of any of the five Lathes into which this county is divided.

In 1841 there were 18,303 inhabited houses with a population of 103,166. To the above may be added the town of Chatham, the city of Rochester, and the borough of Maidstone, containing together 10,570 acres (4,280 ha), and a population of 51,260.[20]

The Lathe of Aylesford consisted of the following Hundreds:

- Brenchley and Horsmonden

- Chatham and Gillingham

- Eyhorne

- Hoo

- Larkfield

- Littlefield

- Maidstone

- Shamwell

- Toltingtrough

- Twyford

- Washlingstone

- West Barnfield

- Wrotham

plus the Lowey of Tonbridge

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The sauna was closed in 2020 due to safety concerns. Campaigners, including the Finnish ambassador to the UK, are working to raise funds for restoration, and have submitted an application for Listed building status to Historic England.[17]

References

[edit]- ^ "Civil Parish population 2011". Neighbourhood Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Archived from the original on 20 October 2016. Retrieved 23 September 2016.

- ^ "Aylesford – The Larkfield Historical Society". www.thelarkfieldsociety.co.uk. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 4 June 2017.

- ^ [1] (Retrieved 3 January 2010) Archived 7 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "2011 Census: Parish population" (PDF). kent.gov.uk. Kent County Council. March 2013. Retrieved 24 January 2017.

- ^ Tonbridge and Malling Borough Council website Archived 13 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 7 November 2009

- ^ Britcher, Chris (24 September 2020). "Plans for £180m redevelopment of Aylesford Newsprint site submitted to Tonbridge and Malling Borough Council". Kent Online. Archived from the original on 18 November 2020. Retrieved 29 October 2022.

- ^ "British Museum - Finds from a Late Iron Age cremation burial". British Museum.

- ^ Cunliffe, Barry W., Iron Age Communities in Britain, Fourth Edition: An Account of England, Scotland and Wales from the Seventh Century BC, Until the Roman Conquest, near Figure 1.4, 2012 (4th edition), Routledge, google preview, with no page numbers

- ^ Swanton, Michael (1998). The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. New York; London: Routledge. pp. xxi–xxviii. ISBN 0-415-92129-5.

- ^ Penguin Classics edition of the Alecto translation: folio 2V: Kent under "In Larkfield Hundred"

- ^ "Friaries - The Carmelite friars of Aylesford | A History of the County of Kent: Volume 2 (pp. 201-203)". British-history.ac.uk. 22 June 2003. Retrieved 14 August 2011.

- ^ "English Priories - Aylesford Priory". The Heritage Trail. Archived from the original on 8 June 2011. Retrieved 14 August 2011.

- ^ "The Friars - Aylseford". thefriars.org.uk.

- ^ "A brief history of Aylesford Church". Aylesford-church.org.uk. Archived from the original on 25 April 2012. Retrieved 2 October 2011.

- ^ Stephen, Paul (6 July 2016). "Made by Britain's bravest". Rail Magazine. No. 804. Peterborough: Bauer Media. p. 60. ISSN 0953-4563.

- ^ "Royal British Legion website". Rblvillage.legionbranches.net. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 14 August 2011.

- ^ Addley, Esther (26 November 2023). "Campaigners seek listed status for Finnish sauna from 1948 London Olympics". The Guardian. Retrieved 27 November 2023.

- ^ Addley, Esther (26 November 2023). "Campaigners seek listed status for Finnish sauna from 1948 London Olympics". The Guardian. Retrieved 27 November 2023.

- ^ a b "Neighbourhood Statistics". Statistics.gov.uk. Retrieved 26 February 2008.

- ^ Bagshaw's History, Gazetteer & Directory of The County of Kent, publ. 1847

External links

[edit]- Aylesford Parish Council

- The Friars website

- Aylesford Bulls Rugby Football Club

- Aylesford - a photoset on Flickr

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Aylesford in the Domesday Book