Metatheria

| Metatheria Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

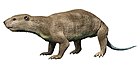

| Lycopsis longirostris, an extinct sparassodont, a relative of the marsupials | |

| |

| A mouse opossum (Marmosa) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Subclass: | Theria |

| Clade: | Metatheria Huxley, 1880 |

| Subgroups | |

| |

Metatheria is a mammalian clade that includes all mammals more closely related to marsupials than to placentals. First proposed by Thomas Henry Huxley in 1880, it is a more inclusive group than the marsupials; it contains all marsupials as well as many extinct non-marsupial relatives. It is one of two groups placed in the clade Theria alongside Eutheria, which contains the placentals.

Description

[edit]Distinctive characteristics (synapomorphies) of Metatheria include: a prehensile tail, the development of a capitular tail on the humerus, the loss of tooth replacement on the 2nd and 5th premolars and the retention of decidious teeth on the lower fifth premolars, the lower canines outwardly diverge from each other, the angular process on the dentary is equal to or less than half the length of the ramus, the dentary has a posterior masseteric shelf, and the lower 5th premolar has a "very trenchant" cristid obliqua/ectolophid. The permanent deciduous lower 5th premolars are molar like and were historically identified as 1st molars, with the third premolar found in basal therians being lost, leaving 4 premolars in the halves of each jaw.[4]

Evolutionary history

[edit]The relationships between the three extant divisions of mammals (monotremes, marsupials, and placentals) was long a matter of debate among taxonomists.[5] Most morphological evidence comparing traits, such as the number and arrangement of teeth and the structure of the reproductive and waste elimination systems, favors a closer evolutionary relationship between marsupials and placental mammals than either has with the monotremes, as does most genetic and molecular evidence.[6]

The earliest possible known metatherian is Sinodelphys szalayi, which lived in China during the Early Cretaceous around 125 million years ago (mya).[7] This makes it a contemporary to some early eutherian species that have been found in the same area.[8] However, Bi et al. (2018) reinterpreted Sinodelphys as an early member of Eutheria. The oldest uncontested metatherians are now 110 million year old fossils from western North America.[3] Metatherians were widespread in Asia and North America during the Late Cretaceous, including both Deltatheroida and Marsupialiformes,[9] with fossils also known from Europe during this time. During the Late Cretaceous, metatherians were more diverse than eutherians in North America.[4] Metatherians underwent a severe decline during the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event, more severe than that suffered by contemporary eutherians and multituberculates, and were slower to recover diversity.[9]

Morphological and species diversity of metatherians in Laurasia remained low in comparison to eutherians throughout the Cenozoic.[10] The two major groups of Cenozoic Laurasian metatherians, the opossum-like herpetotheriids and peradectids persisted into the Miocene before becoming extinct, with the North American herpetotheriid Herpetotherium, the European herpetotheriid Amphiperatherium and the peradectids Siamoperadectes and Sinoperadectes from Asia being the youngest Laurasian non-marsupial metatherians (with marsupials invading North America during the Pliocene-Pleistocene as part of the Great American interchange).[11][9] Metatherians first arrived in Afro-Arabia during the Paleogene, probably from Europe, including the possible peradectoid Kasserinotherium from the Early Eocene of Tunisia and the herpetotheriid Peratherium africanum from the Early Oligocene of Egypt and Oman. The youngest African metatherian is the possible herpetotheriid Morotodon from the late Early Miocene of Uganda.[12][13]

Metatherians arrived in South America from North America during the latest Cretaceous or Paleocene and underwent a major diversificiation, with South American metatherians including both the ancestors of extant marsupials as well as the extinct Sparassodonta, which were major predators in South American ecosystems during most of the Cenozoic, up until their extinction in the Pliocene, as well as the Polydolopimorphia, which likely had a wide range of diets.[10] The oldest known Australian marsupials are from the early Eocene, and are thought to have arrived in the region after having dispersed via Antarctica from South America. The only known Antarctic metatherians are from the Early Eocene La Meseta Formation of the Antarctic Peninsula, where they are the most diverse group of mammals, and include marsupials as well as polydolopimorphians.[10]

Classification

[edit]Below is a metatherian cladogram from Wilson et al. (2016):[14]

| Metatheria |

| ||||||||||||

Cladogram after[15]:

| Metatheria | |

Below is a listing of metatherians that do not fall readily into well-defined groups.

Basal Metatheria

- †Archaeonothos henkgodthelpi Beck 2015

- †Esteslestes ensis Novacek et al. 1991

- †Ghamidtherium dimaiensis Sánches-Villagra et al. 2007

- †Kasserinotherium tunisiense Crochet 1989

- †Palangania brandmayri Goin et al. 1998

- †Perrodelphys coquinense Goin et al. 1999

Ameridelphia incertae sedis:

- †Apistodon exiguus (Fox 1971) Davis 2007

- †Cocatherium lefipanum Goin et al. 2006

- †Dakotadens morrowi Eaton 1993

- †Iugomortiferum thoringtoni Cifelli 1990b

- †Marambiotherium glacialis Goin et al. 1999

- †Marmosopsis juradoi Paula Couto 1962 [Marmosopsini Kirsch & Palma 1995]

- †Pascualdelphys fierroensis

- †Progarzonia notostylopense Ameghino 1904

- †Protalphadon Cifelli 1990

Marsupialia incertae sedis:

- †Itaboraidelphys camposi Marshall & de Muizon 1984

- †Mizquedelphys pilpinensis Marshall & de Muizon 1988

- †Numbigilga ernielundeliusi Beck et al. 2008 {Numbigilgidae Beck et al. 2008}

References

[edit]- ^ O'Leary, Maureen A.; Bloch, Jonathan I.; Flynn, John J.; Gaudin, Timothy J.; Giallombardo, Andres; Giannini, Norberto P.; Goldberg, Suzann L.; Kraatz, Brian P.; Luo, Zhe-Xi; Meng, Jin; Ni, Michael J.; Novacek, Fernando A.; Perini, Zachary S.; Randall, Guillermo; Rougier, Eric J.; Sargis, Mary T.; Silcox, Nancy b.; Simmons, Micelle; Spaulding, Paul M.; Velazco, Marcelo; Weksler, John R.; Wible, Andrea L.; Cirranello, A. L. (8 February 2013). "The Placental Mammal Ancestor and the Post–K-Pg Radiation of Placentals". Science. 339 (6120): 662–667. Bibcode:2013Sci...339..662O. doi:10.1126/science.1229237. hdl:11336/7302. PMID 23393258. S2CID 206544776.

- ^ C.V. Bennett; P. Francisco; F. J. Goin; A. Goswami (2018). "Deep time diversity of metatherian mammals: implications for evolutionary history and fossil-record quality". Paleobiology. 44 (2): 171–198. Bibcode:2018Pbio...44..171B. doi:10.1017/pab.2017.34. hdl:11336/94590.

- ^ a b S. Bi; X. Zheng; X. Wang; N.E. Cignetti; S. Yang; J.R. Wible (2018). "An Early Cretaceous eutherian and the placental–marsupial dichotomy". Nature. 558 (7710): 390–395. Bibcode:2018Natur.558..390B. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0210-3. PMID 29899454. S2CID 49183466.

- ^ a b Williamson, Thomas E.; Brusatte, Stephen L.; Wilson, Gregory P. (17 December 2014). "The origin and early evolution of metatherian mammals: the Cretaceous record". ZooKeys (465): 1–76. Bibcode:2014ZooK..465....1W. doi:10.3897/zookeys.465.8178. ISSN 1313-2970. PMC 4284630. PMID 25589872.

- ^ Moyal, Ann Mozley (2004). Platypus: The Extraordinary Story of How a Curious Creature Baffled the World. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8052-0.

- ^ van Rheede, T.; Bastiaans, T.; Boone, D.; Hedges, S.; De Jong, W.; Madsen, O. (2006). "The platypus is in its place: nuclear genes and indels confirm the sister group relation of monotremes and therians". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 23 (3): 587–597. doi:10.1093/molbev/msj064. PMID 16291999.

- ^ Rincon, Paul (12 December 2003). "Oldest Marsupial Ancestor Found, BBC, Dec 2003". BBC News. Retrieved 16 March 2010.

- ^ Hu, Yaoming; Meng, Jin; Li, Chuankui; Wang, Yuanqing (2010). "New basal eutherian mammal from the Early Cretaceous Jehol biota, Liaoning, China". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 277 (1679): 229–236. doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.0203. PMC 2842663. PMID 19419990.

- ^ a b c Bennett, C. Verity; Upchurch, Paul; Goin, Francisco J.; Goswami, Anjali (6 February 2018). "Deep time diversity of metatherian mammals: implications for evolutionary history and fossil-record quality". Paleobiology. 44 (2): 171–198. Bibcode:2018Pbio...44..171B. doi:10.1017/pab.2017.34. hdl:11336/94590. ISSN 0094-8373. S2CID 46796692.

- ^ a b c Eldridge, Mark D B; Beck, Robin M D; Croft, Darin A; Travouillon, Kenny J; Fox, Barry J (23 May 2019). "An emerging consensus in the evolution, phylogeny, and systematics of marsupials and their fossil relatives (Metatheria)". Journal of Mammalogy. 100 (3): 802–837. doi:10.1093/jmammal/gyz018. ISSN 0022-2372.

- ^ Furió, Marc; Ruiz-Sánchez, Francisco J.; Crespo, Vicente D.; Freudenthal, Matthijs; Montoya, Plinio (July 2012). "The southernmost Miocene occurrence of the last European herpetotheriid Amphiperatherium frequens (Metatheria, Mammalia)". Comptes Rendus Palevol. 11 (5): 371–377. Bibcode:2012CRPal..11..371F. doi:10.1016/j.crpv.2012.01.004.

- ^ Crespo, Vicente D.; Goin, Francisco J. (21 June 2021). "Taxonomy and Affinities of African Cenozoic Metatherians". Spanish Journal of Palaeontology. 36 (2). doi:10.7203/sjp.36.2.20974. hdl:11336/165007. ISSN 2255-0550. S2CID 237387495.

- ^ Crespo, Vicente D.; Goin, Francisco J.; Pickford, Martin (3 June 2022). "The last African metatherian". Fossil Record. 25 (1): 173–186. doi:10.3897/fr.25.80706. hdl:10362/151025. ISSN 2193-0074. S2CID 249349445.

- ^ Wilson, G.P.; Ekdale, E.G.; Hoganson, J.W.; Calede, J.J.; Linden, A.V. (2016). "A large carnivorous mammal from the Late Cretaceous and the North American origin of marsupials". Nature Communications. 7: 13734. Bibcode:2016NatCo...713734W. doi:10.1038/ncomms13734. PMC 5155139. PMID 27929063.

- ^ Ladevèze, Sandrine; Selva, Charlène; de Muizon, Christian (1 September 2020). "What are "opossum-like" fossils? The phylogeny of herpetotheriid and peradectid metatherians, based on new features from the petrosal anatomy". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 18 (17): 1463–1479. doi:10.1080/14772019.2020.1772387. ISSN 1477-2019.