Borders of Suriname

The borders of Suriname consist of land borders with three countries: Guyana, Brazil, and France (via French Guiana). The borders with Guyana and France are in dispute, but the border with Brazil has been uncontroversial since 1906.

Eastern border

[edit]

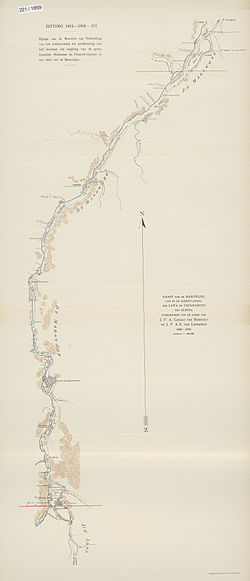

In 1860, the question was posed from the French side, which of the two tributary rivers of the Marowijne River (also called Maroni and Marowini) was the headwater, and thus the border. A joint French-Dutch commission was appointed to review the issue. The Dutch side of the commission consisted of J.H. Baron van Heerdt tot Eversberg, J.F.A. Cateau van Rosevelt and August Kappler. Luits Vidal, Ronmy, Boudet and Dr. Rech composed the French side. In 1861 measurements were taken, which produced the following result: the Lawa had a flow rate of 35,960 m3/minute at a width of 436 m; the Tapanahony had a flow rate of 20,291 m3/minute at a width of 285 m. Thus, the Lawa River was the headwater of the Maroni River.

There were no problems with this decision until 1885, when the discovery of gold in the area between the Lawa and the Tapanahony created a new border conflict. On November 29, 1888, France and the Netherlands reached an agreement that the conflict should be subject to arbitration. Tsar Alexander III of Russia, acting as the arbitrator, decided that the Lawa was the headwater of the Maroni, and thus should be considered the border. The Netherlands and France concluded a border treaty on this section of the river on 30 September 1915. A protocol delineating the border from the mouth of the Maroni up to the village of Antecume Pata was attached to this treaty on 15 March 2021.[1]

However, neither the 1915 treaty nor the 2021 protocol determines which river is the source of the Lawa. The Netherlands considered the Malani (Dutch: Marowijnekreek) to be the source of the Lawa; the French considered the Litani, located further to the west, to be the source of the Lawa. This issue has still not been resolved.[2]

The Litani originates in the Tumuk Humak Mountains at approximately 2½° N 55° W; along its path it is fed by Koele Koelekreek, the Lokekreek, the Mapaonikreek and the Oelemari River.

The Malani also has its source in the Tumuk Humak Mountains, at approximately 2° N, 54° W; it also absorbs the Koelebreek, among others.

Western border

[edit]

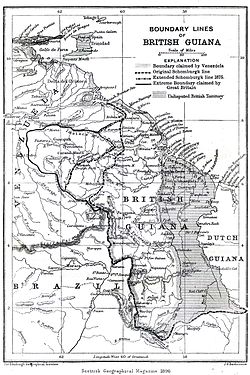

According to an agreement between Suriname governor Cornelis van Aerssen van Sommelsdijck and Berbice governor Abraham van Pere—both were Dutch colonies at the time—the border between the two colonies was located at Devil Creek, between the Berbice River and the Courantyne River. In 1799, however, Berbice governor Abraham Jacob van Imbijze van Batenburg and Suriname governor Jurriaan François de Friderici signed an agreement in which the western bank of the Courantyne River was demarcated as the boundary. All islands in the Courantyne, as well as the post at Orealla, were deemed to be in Suriname.[3] As the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1814 returned Suriname to Dutch rule in the boundaries of 1 January 1803, the Courantyne became the new boundary between British Guiana and Suriname.

New River Triangle

[edit]

Robert Schomburgk surveyed British Guiana's borders in 1840. Taking the Courantyne River as the border, he sailed up to which he deemed its source, the Kutari River, in order to delineate the boundary. In 1871, however, Charles Barrington Brown discovered the New River or Upper Courantyne, which is the source of the Courantyne. Thus the New River Triangle dispute was born.

The tribunal which dealt with the Venezuelan crisis of 1895 also awarded the New River Triangle to British Guiana. The Netherlands, however, raised a diplomatic protest, claiming that the New River, and not the Kutari, was to be regarded as the source of the Courantyne and the boundary. The British government in 1900 replied that the issue was already settled by the long acceptance of the Kutari as the boundary.

In 1936, a Mixed Commission established by the British and Dutch government agreed to award the full width of the Courantyne River to Suriname, as per the 1799 agreement. The territorial sea boundary was deemed to prolongate 10° from Point No. 61, 6 km (3 nmi) from the shore. The New River Triangle, however, was completely awarded to Guyana. The treaty putting this agreement into law was never ratified, because of the outbreak of World War II.[4] That same year, the Dutch representative Conrad Carel Käyser signed an agreement with British and Brazilian representatives, placing the tri-point junction near the source of the Kutari River.[5]

Desiring to put the border issue to a closure before British Guiana would gain independence, the British government restarted negotiations in 1961. The British position asserted "Dutch sovereignty over the Corentyne River, a 10° line dividing the territorial sea, and British control over the New River Triangle."[6] The Netherlands replied with a formal claim to the New River Triangle, but with a thalweg boundary in the Courantyne River (the latter position has never been repeated by any Surinamese government). No agreements were made and Guyana became independent with its borders unresolved. In 1969 border skirmishes occurred between Guyanese forces and Surinamese militias at Camp Tigri. In 1971, the Surinamese and Guyanese government agreed in Trinidad to withdraw military forces from the Triangle. Until present Guyana hasn't withdrawn any of its military forces and still holds a firm grip on the New River Triangle.[citation needed]

Maritime dispute

[edit]The maritime boundary has long been disputed between Guyana and Suriname as well, and led in 2000 to skirmishes between Guyanese oil explorers and Surinamese coast guards.[7] Guyana claimed a thalweg boundary of the Courantyne River (probably inspired by the 1962 Dutch position), and a 35° line from the true North, from the mouth of the river. Suriname claimed sovereignty over the full width of the Courantyne and a 10° dividing line. Eventually a five-member tribunal of the Permanent Court of Arbitration was convened under the rules set out in Annex VII of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, which in 2007 set out its own boundary that differed from both parties' claims. The maritime border was finally settled by international arbitration.[8] The tribunal did award sovereignty over the full width of the Courantyne to Suriname, and also awarded Suriname with a 10° territorial sea boundary 6 km (3 nmi) from the shore, according to the 1936 agreement. The rest of the territorial sea boundary, which extends 22 km (12 nmi) from the shore under modern international law, and the boundary separating the Exclusive Economic Zones of both countries, was awarded according to the principle of equidistance, however.[9][10]

Southern border

[edit]The southern border with Brazil is described in the Treaty of Limits of 1906 as "formed from the French border French Guiana to the British border British Guiana, the line of the drainage divide (watershed) between the Amazon basin to the south, and the basins of the rivers flowing into north to the Atlantic Ocean." The border described in the treaty was the result of an arbitration process that was headed by King Victor Emmanuel III of Italy. The treaty was signed in Rio de Janeiro on May 5, 1906. Brazil and the Netherlands both ratified the treaty in 1908.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Protocol tussen de Republiek Suriname en de Franse Republiek met het oog op de Regeling van de Grens tussen Suriname en Frans-Guyana over de Marowijne en Lawarivier bij het Verdrag getekend in Parijs op 30 september 1915 tot het vaststellen van de Grens in een deel van de Grensrivier

- ^ Guyane française – Suriname : le tracé définitif de la frontière officiellement fixé sur 400 km

- ^ See De Grenzen van Nederlandsch Guiana by Dr. H.D. Benjamins, T.A.G. December 1898.

- ^ Donovan 2003, p. 58

- ^ Donovan 2003, pp. 56–57

- ^ Donovan 2003, p. 60

- ^ Donovan 2003, p. 62

- ^ Alexander Aizenstatd- Guyana v Suriname Boundary Arbitration. Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law. 2011

- ^ Permanent Court of Arbitration - Guyana/Suriname Archived 2013-02-08 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Award of the Tribunal Archived 2011-01-02 at the Wayback Machine

References

[edit]- Donovan, Thomas W. (2003). "Suriname-Guyana Maritime and Territorial Disputes: A Legal and Historical Analysis" (PDF). Journal of Transnational Law and Policy. 13 (1): 41–99. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-08-13.

- Aizenstatd, Alexander (2011). "Guyana v Surinam Boundary Arbitration". The Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law.

Further reading

[edit]- Menon, P.K. (1978). "International Boundaries: A Case Study of the Guyana-Surinam Boundary". The International and Comparative Law Quarterly. 27 (4): 738–768. doi:10.1093/iclqaj/27.4.738. JSTOR 758476.

- Hoyle, Peggy A. (Summer 2001). "The Guyana-Suriname Maritime Boundary Dispute and its Regional Context" (PDF). IBRU Boundary and Security Bulletin: 99–107.