Jersey

Jersey Jèrri (Jèrriais) | |

|---|---|

British Crown Dependency | |

| Bailiwick of Jersey | |

| Motto: | |

| Anthem: "God Save the King" | |

| Island anthem: "Island Home"[3] | |

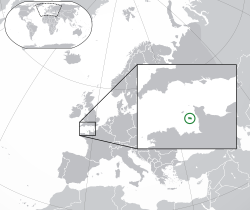

Location of Jersey (green) in Europe (dark grey) | |

| Sovereign state responsible for Jersey[1][2] | United Kingdom |

| Separation from the Duchy of Normandy | 1204 |

| Capital and largest parish[b] | St Helier[a] 49°11.4′N 2°6.6′W / 49.1900°N 2.1100°W |

| Official languages | |

| Ethnic groups (2021)[4] | |

| Religion (2015)[5] |

|

| Demonym(s) | Islanders, Jerseyman, Jerseywoman, Jersey bean, Jersey crapaud, Jèrriais(e) |

| Government | Parliamentary constitutional monarchy |

| Charles III | |

| Jerry Kyd | |

• Bailiff | Sir Tim Le Cocq |

| Lyndon Farnham | |

| Legislature | States Assembly |

| Area | |

• Total | 119.6[6] km2 (46.2 sq mi) (unranked) |

• Water (%) | 0 |

| Highest elevation | 469 ft (143 m) |

| Population | |

• 2021 census | 103,267[7] |

• Density | 859/km2 (2,224.8/sq mi) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2015 estimate |

• Total | billion (£4.57 billion)[8] (not ranked) |

• Per capita | (£45,783) (not ranked) |

| GDP (nominal) | 2019 estimate |

• Total | £4.885 billion (US billion)[9] |

• Per capita | £45,320 |

| Gini (2014) | low |

| HDI (2011) | very high · not ranked |

| Currency | Pound sterling Jersey pound (£) (GBP) |

| Time zone | UTC±00:00 (GMT) |

• Summer (DST) | UTC+01:00 (BST) |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy |

| Mains electricity | 230 V–50 Hz |

| Driving side | left |

| Calling code | +44 |

| UK postcode | |

| ISO 3166 code | JE |

| Internet TLD | .je |

Jersey (/ˈdʒɜːrzi/ JUR-zee; Jèrriais: Jèrri [ʒɛri]), officially known as the Bailiwick of Jersey,[d][12][13][14] is an island country and self-governing British Crown Dependency near the coast of north-west France.[15][16][17] It is the largest of the Channel Islands and is 14 miles (23 km) from the Cotentin Peninsula in Normandy.[18] The Bailiwick consists of the main island of Jersey and some surrounding uninhabited islands and rocks including Les Dirouilles, Les Écréhous, Les Minquiers, and Les Pierres de Lecq.[19]

Jersey was part of the Duchy of Normandy, whose dukes became kings of England from 1066. After Normandy was lost by the kings of England in the 13th century, and the ducal title surrendered to France, Jersey remained loyal to the English Crown, though it never became part of the Kingdom of England. Between then and the end of the Napoleonic Wars, Jersey was at the frontline of Anglo-French Wars and was invaded a number of times, leading to the construction of fortifications such as Mont Orgueil Castle and a thriving smuggling industry. During the Second World War, the island was invaded and occupied for five years by Nazi Germany. The island was liberated on 9 May 1945, which is now celebrated as the island's national day.[20]

Jersey is a self-governing parliamentary democracy under a constitutional monarchy, with its own financial, legal and judicial systems,[7] and the power of self-determination.[21] Jersey's constitutional relationship is with the Crown; it is not part of the United Kingdom.[22][23][24] The bailiff is the civil head, president of the states and head of the judiciary; the lieutenant governor represents the head of state, the British monarch; and the chief minister is the head of government. Jersey's defence and international representation – as well as certain policy areas, such as nationality law – are the responsibility of the UK government, but Jersey still has a separate international identity.[25]

The island has a large financial services industry, which generates 40% of its GVA.[6] British cultural influence on the island is evident in its use of English as the main language and pound sterling as its primary currency. Additional British cultural similarities include: driving on the left, access to British television, newspapers and other media, a school curriculum following that of England,[26] and the popularity of British sports, including football and cricket.[27] The island also has a strong Norman-French culture, such as its historic dialect of the Norman language, Jèrriais, being one of only two places in Normandy with government status for the language (the other being Guernsey), as well as the use of standard French in legal matters and officially in use as a government language, strong cultural ties to mainland Normandy as a part of the Normandy region, and place names with French or Norman origins. The island has very close cultural links with its neighbouring islands in the Bailiwick of Guernsey, and they share a good-natured rivalry. Jersey and its people have been described as a nation.[28][29][30]

Name

[edit]The Channel Islands are mentioned in the Antonine Itinerary as the following: Sarnia, Caesarea, Barsa, Silia and Andium, but Jersey cannot be identified specifically because none corresponds directly to the present names.[31] The name Caesarea has been used as the Latin name for Jersey (also in its French version Césarée) since William Camden's Britannia,[32] and is used in titles of associations and institutions today. The Latin name Caesarea was also applied to the colony of New Jersey as Nova Caesarea.[33][34]

Andium, Agna and Augia were used in antiquity.[35][36]

Scholars variously surmise that Jersey and Jèrri derive from jǫrð (Old Norse for 'earth') or jarl ('earl'), or perhaps the Norse personal name Geirr (thus Geirrsey, 'Geirr's Island').[37] The ending -ey denotes an island[38][39] (as in Guernsey or Surtsey).

History

[edit]

Humans have lived on the island since at least 12,000 BCE, with evidence of habitation in the Palaeolithic period (La Cotte de St Brelade) and Neolithic dolmens, such as La Hougue Bie. Evidence of Bronze Age and early Iron Age settlements can be found in many locations around the island.[40]

Archaeological evidence of Roman influence has been found, in particular at Les Landes.[41] Christianity was brought to the island by migrants from Brittany in c. fifth – sixth century CE.[42] In the sixth century, the island's patron saint Helier lived at the Hermitage on L'Islet (now Elizabeth Castle). Legend states that Helier was beheaded by raiders and subsequently lifted his head and walked to shore.[43]

In the ninth century the island was raided by Vikings and in 933 it was annexed to Normandy by William Longsword.[44]: 22 When Duke William the Conqueror became King of England in 1066, the island remained part of the Norman possessions. However, in 1204, when Normandy was returned to the French king, the island remained a possession of the English crown, though never incorporated into England.[42]: 25 Traditionally it is said that Jersey's self-governance originates from the Constitutions of King John, however this is disputed.[44]: 25 Nevertheless, the island continued to follow Norman customs and laws. The King also appointed a Bailiff and a Warden (now Lieutenant-Governor). The period of English rule was marked by wars between England and France, as such a military fortress was built at Mont Orgueil.[42]: 25–8

During the Tudor period, the split between the Church of England and the Vatican led to islanders adopting the Protestant religion. During the reign of Elizabeth, French refugees brought strict Calvinism to the island, which remained the common religion until 1617.[42] In the late 16th century, islanders travelled across the North Atlantic to participate in the Newfoundland fisheries.[45] In recognition for help given to him during his exile in Jersey in the 1640s, King Charles II of England gave Vice Admiral Sir George Carteret, bailiff and governor, a large grant of land in the American colonies in between the Hudson and Delaware rivers, which he promptly named New Jersey. It is now a state in the United States.[46][47]

In 1769, the island suffered food supply shortages, leading to an insurrection on 28 September known as the Corn Riots. The States met at Elizabeth Castle and decided to request help from the King. However, in 1771 the Crown demanded reforms to the island's governance, leading to the Code of 1771 and removed the powers of the Royal Court to make laws without the States.[42] In 1781, during the American Revolutionary War, the island was invaded by a French force which captured St Helier, but was defeated by Major Peirson's army at the Battle of Jersey.[48]

The 19th century saw the improvement of the road network under General Don,[49] the construction of two railway lines, the improvement of transport links to England, and the construction of new piers and harbours in St Helier.[42] This grew a tourism industry in the island and led to the immigration of thousands of English residents, leading to a cultural shift towards a more anglicised island culture. Island politics was divisively split between the conservative Laurel party and the progressive Rose party, as the lie of power shifted increasingly to the States from the Crown.[42] In the 1850s, the French author Victor Hugo lived in Jersey, but was expelled for insulting the Queen, so he moved on to Guernsey.[42]

During the Second World War, 6,500 Jersey residents were evacuated by their own choice to the UK out of a total population of 50,000.[50] Jersey was occupied by Germany from 1 July 1940 until 9 May 1945, when Germany surrendered.[51] During this time the Germans constructed many fortifications using slave labour imported onto the island from many different countries occupied or at war with Germany.[52] After 1944, supplies from France were interrupted by the D-Day landings, and food on the island became scarce. The SS Vega was sent to the island carrying Red Cross supplies and news of the success of the Allied advance in Europe. During the Nazi occupation, a resistance cell was created by communist activist Norman Le Brocq and the Jersey Communist Party, whose communist ideology of forming a 'United Front' led to the creation of the Jersey Democratic Movement.[53] The Channel Islands had to wait for the German surrender to be liberated. 9 May is celebrated as the island's Liberation Day, where there are celebrations in Liberation Square. After Liberation, the States was reformed, becoming wholly democratically elected, and universal franchise was implemented. Since liberation, the island has grown in population and adopted new industries, especially the finance industry.[42]

Politics

[edit]

Jersey is a Crown Dependency and is not part of the United Kingdom – it is officially part of the British Islands. As one of the Crown Dependencies, Jersey is autonomous and self-governing, with its own independent legal, administrative and fiscal systems.[54] Jersey's government has described Jersey as a "self-governing, democratic country with the power of self-determination".[55]

Because Jersey is a dependency of the British Crown, King Charles III reigns in Jersey.[56] "The Crown" is defined by the Law Officers of the Crown as the "Crown in right of Jersey".[57] The King's representative and adviser in the island is the Lieutenant Governor of Jersey – Vice-Admiral Jerry Kyd since 8 October 2022. He is a point of contact between Jersey ministers and the UK Government and carries out some functions in relation to immigration control, deportation, naturalisation and the issue of passports.[58]

In 1973, the Royal Commission on the Constitution set out the duties of the Crown as including: ultimate responsibility for the 'good government' of the Crown Dependencies; ratification of island legislation by Order-in-Council (royal assent); international representation, subject to consultation with the island authorities before concluding any agreement which would apply to them; ensuring the islands meet their international obligations; and defence.[59]

Legislature and government

[edit]Jersey's unicameral legislature is the States Assembly. It includes 49 elected members: 12 connétables (often called "constables", heads of parishes) and 37 deputies (representing constituencies), all elected for four-year terms as from the October 2011 elections.[60] Jersey has one of the lowest voter turnouts internationally, with just 33% of the electorate voting in 2005, putting it well below the 77% European average for that year.[61]

From the 2022 elections, the role of senators was abolished and the eight senators were replaced with an increased number of deputies. The 37 deputies are now elected from nine super constituencies, rather than in individual parishes. Although efforts were made the remove the connétables, they will continue their historic role as states members.[62]

There are also five non-voting members appointed by the Crown: the bailiff, the Lieutenant Governor of Jersey, the Dean of Jersey, the attorney general and solicitor general.[63] The Bailiff is President (presiding officer) of the States Assembly,[64] head of the judiciary and as civic head of the island carries out various ceremonial roles.[65]

The Council of Ministers, consisting of a chief minister and nine ministers, makes up the leading body of the government of Jersey.[66][67] Each minister may appoint up to two assistant ministers.[68] A chief executive is head of the civil service.[69] Some governmental functions are carried out in the island's parishes.[70]

Law

[edit]Jersey is a distinct jurisdiction for the purposes of conflict of laws, separate from the other Channel Islands, England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland.[71]

Jersey law has been influenced by several different legal traditions, in particular Norman customary law, English common law and modern French civil law.[72] Jersey's legal system is therefore described as 'mixed' or 'pluralistic', and sources of law are in French and English languages, although since the 1950s the main working language of the legal system is English.[73]

The principal court is the Royal Court, with appeals to the Jersey Court of Appeal and, ultimately, to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council.[74] The Bailiff is head of the judiciary; the Bailiff and the Deputy Bailiff are appointed by the Crown. Other members of the island's judiciary are appointed by the Bailiff.[65]

External relations

[edit]

The external relations of Jersey are overseen by the External Relations Minister of the Government of Jersey.[75][76] In 2007, the chief minister and the UK Lord Chancellor signed an agreement that established a framework for the development of the international identity of Jersey.[77]

Although diplomatic representation is reserved to the Crown, Jersey has been developing its own international identity over recent years. It negotiates directly with foreign governments on various matters, for example, tax information exchange agreements (TIEAs) have been signed directly by the island with several countries.[78][79] The government maintains offices (some in partnership with Guernsey) in Caen,[80] London[81] and Brussels.[82]

Jersey is a member of the British-Irish Council,[83] the Commonwealth Parliamentary Association[84] and the Assemblée parlementaire de la Francophonie.[85]

Jersey independence has in the past been discussed in the States Assembly. Former external relations minister, Sir Philip Bailhache, has at various times warned that the island may need to become independent.[86] It is not Jersey government policy to seek independence, but the island is prepared if needs to do so.[87][88][89]

Jersey is a third-party European country to the EU. Since 1 January 2021, Jersey has been part of the UK-EU Trade and Economic Cooperation Agreement for the purposes of goods and fishing. Goods exported from the island into Europe are not subject to tariffs and Jersey is solely responsible for management of its territorial waters, however permits may be granted to EU fishermen who have a history of fishing in the Bailiwick's waters. The management of this permit system has caused tension between the French and Jersey authorities, with the French threatening to cut off Jersey's electricity supply in May 2021.[90] Before the end of the transition period after the UK withdrew from the EU in 2020, Jersey had a special relationship with the EU.[e] It was part of the EU customs union and there was free movement of goods between Jersey and the EU, but the single market in financial services and free movement of people did not apply to Jersey.[91][92]

Jersey also has close relations with Portugal including the exchangement of tax information, these relations are specifically strong with the Autonomous Region of Madeira, where St.Helier has one of its sister cities (Funchal).[93]

Administrative divisions

[edit]Jersey is divided into twelve parishes (which have civil and religious functions). They are all named after their parish church. The connétable is the head of the parish. They are elected at island general elections and sit ex oficio in the States Assembly.[70]

The parishes have various civil administrative functions, such as roads (managed by the Road Committee) and policing (through the Honorary Police). Each parish is governed through direct democracy at parish assemblies, consisting of all eligible voters resident in the parish. The Procureurs du Bien Public are the legal and financial representatives of these parishes.[70]

The parishes of Jersey are further divided into vingtaines (or, in St. Ouen, cueillettes).[94]

Geography

[edit]

Jersey is an island measuring 46.2 square miles (119.6 km2) (or 66,436 vergées),[6] including reclaimed land and intertidal zone. It lies in the English Channel, about 12 nautical miles (22 km; 14 mi) from the Cotentin Peninsula in Normandy, France, and about 87 nautical miles (161 km; 100 mi) south of Great Britain.[f] It is the largest and southernmost of the Channel Islands and part of the British Isles, with a maximum land elevation of 143 m (469 ft) above sea level.[95]

About 24% of the island is built-up. 52% of the land area is dedicated to cultivation and around 18% is the natural environment.[96]

It lies within longitude -2° W and latitude 49° N. It has a coastline that is 43 miles (70 km) long and a total area of 46.2 square miles (119.6 km2). It measures roughly 9 miles (14 km) from west to east and 5 miles (8 km) north to south, which gives it the affectionate name among locals of "nine-by-five".[97]

The island is divided into twelve parishes; the largest is St Ouen and the smallest is St Clement. The island is characterised by a number of valleys which generally run north-to-south, such as Waterworks Valley, Grands Vaux, Mont les Vaux, although a few run in other directions, such as Le Mourier Valley. The highest point on the island is Les Platons at 136 m (446 ft).[98]

There are several smaller island groups that are part of the Bailiwick of Jersey, such as Les Minquiers and Les Écrehous, however unlike the smaller islands of the Bailiwick of Guernsey, none of these are permanently inhabited.[99]

Settlements

[edit]The largest settlement is the town of St Helier, including the built-up area of southern St Helier and neighbouring areas such as Georgetown, which also plays host to the island's seat of government. The town is the central business district, hosting a large proportion of the island's retail and employment, such as the finance industry.[100]

Outside of the town, many islanders live in suburban and rural settlements, especially along main roads leading out of town and even the more rural areas of the island have considerable amounts of development (St Ouen, the least densely populated parish still has 270 persons per square kilometre[101]). The south and east coasts from St Aubin to Gorey are largely urbanised. The second smaller urban area is the Les Quennevais area in St Brelade, which is home to a small precinct of shops,[102] a school, a park and a leisure centre.[103]

Most people across Jersey regularly travel from the rural settlements to St Helier and from the town to the rural areas for work and leisure purposes.[104]

Housing costs in Jersey are very high. The Jersey House Price Index has at least doubled between 2002 and 2020. The mix-adjusted house price for Jersey is £567,000, higher than any UK region (UK average: £249,000) including London (average: £497,000; highest of any UK region).[105]

Climate

[edit]The island has an oceanic climate with mild winters and mild to warm summers.[106] The highest temperature recorded was 37.9 °C (100.2 °F), on 18 July 2022,[107] and the lowest temperature recorded was −10.3 °C (13.5 °F), on 5 January 1894. 2022 was the warmest (and sunniest) year on record; the mean daily air temperature was 13.56 °C.[108] For tourism advertising, Jersey often claims to be "the sunniest place in the British Isles", as Jersey has over 1,900 hours of sunlight. Jersey is indeed one of the sunniest places in the British Isles as its southern location in the English channel inhibits the type of convective cloud formation which tends to stick to larger landmasses. Furthermore, the islands lower latitude means ridges extending from the Azores High influence the islands climate to a larger extent compared with mainland Great Britain, further preventing cloud formation through subsidence.

Snow is very rare in Jersey. The last significant snowfall event occurred in March 2013, where 5.5 inches (14cm) of snow fell.[109] However, the most recent measurable snowfall event occurred on the 8th/9th of January 2024, where 3-5cm of snow fell, significantly more than forecasted.[110]

Extreme weather is rare due to the islands mild and generally cool climate. Summer thunderstorms originating from the European mainland occasionally occur but are usually not severe. In November 2023, Jersey was hit by extratropical Storm Ciaran, causing heavy rainfall, extremely high winds with gusts of up to 104mph[111]. A supercell thunderstorm associated with the cold front of this system hit Jersey at around midnight on the 2nd November 2023. With severe wind shear and exceptional storm relative helicity, moderate surface CAPE, extremely low atmospheric pressure, the lifting mechanism of the cold front, moisture from southwesterlies and temperature contrast of the upper atmosphere and sea surface, the storm produced extremely large hail and a tornado, which devastated the eastern half of the Island and was subsequently rated T6/EF3 by TORRO, making it one of the most severe tornadoes ever recorded in the British Isles.[112]

In 2011, Jersey generated controversy for calling itself "the warmest place in the British Isles" during an advertising campaign, as Jersey is neither the place with the highest maximum temperature in the British Isles (40.3°C was recorded in Coningsby, Lincolnshire in July 2022[113]) or the highest winter temperatures in the British Isles (which would be the Isles of Scilly).[114]

Typical wind speeds vary between 20 kilometres per hour (12 mph) and 40 kilometres per hour (25 mph)

The Government of Jersey's official meteorological department provides an accurate 5-day forecast for Jersey and Guernsey, including detailed shipping forecasts and aviation forecasts.

The following table contains the official data for 1981–2010 at Jersey Airport, located 4.5 miles (7.2 km) from St. Helier –

| Climate data for Jersey Airport, elevation 84m, 1981–2010 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 14.0 (57.2) |

18.0 (64.4) |

20.3 (68.5) |

25.0 (77.0) |

28.0 (82.4) |

33.0 (91.4) |

37.9 (100.2) |

36.0 (96.8) |

30.2 (86.4) |

26.0 (78.8) |

21.0 (69.8) |

16.0 (60.8) |

37.9 (100.2) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 8.3 (46.9) |

8.4 (47.1) |

10.4 (50.7) |

12.5 (54.5) |

15.8 (60.4) |

18.4 (65.1) |

20.4 (68.7) |

20.6 (69.1) |

18.7 (65.7) |

15.4 (59.7) |

11.7 (53.1) |

9.2 (48.6) |

14.2 (57.6) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 6.3 (43.3) |

6.1 (43.0) |

7.9 (46.2) |

9.5 (49.1) |

12.6 (54.7) |

15.1 (59.2) |

17.2 (63.0) |

17.5 (63.5) |

15.8 (60.4) |

13.0 (55.4) |

9.6 (49.3) |

7.1 (44.8) |

11.5 (52.7) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 4.3 (39.7) |

3.8 (38.8) |

5.3 (41.5) |

6.5 (43.7) |

9.3 (48.7) |

11.8 (53.2) |

13.9 (57.0) |

14.3 (57.7) |

12.9 (55.2) |

10.6 (51.1) |

7.5 (45.5) |

5.0 (41.0) |

8.8 (47.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −10.3 (13.5) |

−9.0 (15.8) |

−3.3 (26.1) |

−1.6 (29.1) |

0.0 (32.0) |

5.9 (42.6) |

9.0 (48.2) |

7.7 (45.9) |

6.0 (42.8) |

−2.6 (27.3) |

−3.0 (26.6) |

−4.0 (24.8) |

−10.3 (13.5) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 93.1 (3.67) |

68.9 (2.71) |

66.1 (2.60) |

56.4 (2.22) |

55.6 (2.19) |

47.5 (1.87) |

44.6 (1.76) |

49.5 (1.95) |

63.9 (2.52) |

103.4 (4.07) |

105.4 (4.15) |

111.3 (4.38) |

865.8 (34.09) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 66.1 | 91.6 | 134.0 | 196.5 | 236.7 | 245.4 | 252.7 | 235.3 | 184.6 | 118.8 | 79.9 | 63.2 | 1,904.8 |

| Source: Met Office[115] and Voodoo Skies[116] | |||||||||||||

Economy

[edit]

Jersey's economy is highly developed and services-focused, with a GDP per capita of £45,320[9] in 2019. It is a mixed market economy, with free market principles and an advanced social security infrastructure.[117] 53,460 people were employed in Jersey as of December 2010[update]: 24% in financial and legal services; 16% in wholesale and retail trades; 16% in the public sector; 10% in education, health and other private sector services; 10% in construction and quarrying; 9% in hotels, restaurants and bars.[6]

| Sector | Gross value added | |

|---|---|---|

| % of total | £millions | |

| Financial services | 39.5% | 1,966 |

| Rental income | 15.5% | 771 |

| Other business activities | 11.7% | 580 |

| Public administration | 8.6% | 426 |

| Construction | 7.0% | 350 |

| Wholesale and retail | 6.4% | 319 |

| Hotels, bars and restaurants | 4.2% | 210 |

| Transport, storage and communication | 3.5% | 176 |

| Electricity, gas and water | 1.3% | 65 |

| Agriculture | 1.2% | 59 |

| Manufacturing | 1.0% | 50 |

| Total | 4,972 | |

Thanks to specialisation in a few high-return sectors, at purchasing power parity Jersey has high economic output per capita, substantially ahead of all of the world's large developed economies. Gross national income in 2009[needs update] was £3.7 billion (a mean of about £40,000 per head of population).[6] However, there is wide variation, and the typical (median) individual resident's purchasing power and standard of living in Jersey is comparable to that in the UK outside central London.[119]

Jersey is one of the world's largest offshore finance centres. The UK acts as a conduit[clarification needed] for financial services between European countries and the island.[120] But there has been some controversy about this sector: some critics and detractors have called Jersey a place where the "leadership has essentially been captured by global finance, and whose members will threaten and intimidate anyone who dissents."[61]

Tourism is an important economic sector for the island, however travel to Jersey is very seasonal. Accommodation occupancy is much higher in the summer months, especially August, than in the winter months (with a low in November). The majority of visitors to the island arrive by air from the UK.[121] On 18 February 2005, Jersey was granted Fairtrade Island status.[122]

In 2017, 52% of the Island's area was agricultural land (a decrease since 2009).[96] Major agricultural products are potatoes and dairy produce.[6] Jersey cattle are a small breed of cow widely known for their rich milk and cream; the quality of their meat is also appreciated on a small scale.[123][124] The herd total in 2009 was 5,090 animals.[6] Fisheries and aquaculture make use of Jersey's marine resources to a total value of over £6 million in 2009.[6]

Along with Guernsey, Jersey has its own lottery called the Channel Islands Lottery, which was launched in 1975.[125]

Taxation

[edit]Jersey is not a tax-free jurisdiction. Taxes are levied on properties (known as 'rates') and there are taxes on personal income, corporate income and goods and services.[126] Before 2008, Jersey had no value-added tax (VAT). Many companies, such as Amazon and Play.com, took advantage of this and a loophole in European law, known as low-value consignment relief, to establish a tax-free fulfilment industry from Jersey.[127] This loophole was closed by the European Union in 2012, resulting in the loss of hundreds of jobs.[127]

There is a 20% standard rate for Income Tax and a 5% standard rate for GST. The island has a 0% default tax rate for corporations; however, higher rates apply to financial services, utility companies and large corporate retailers.[126] Jersey is considered to be a tax haven. Until March 2019 the island was on the EU tax haven blacklist, but it no longer features on it.[128] In January 2021, the chair of the EU Tax Matters Subcommittee, Paul Tang, criticised the list for not including such "renowned tax havens" as Jersey.[129] In 2020, Tax Justice ranked Jersey as the 16th on the Financial Secrecy Index, below larger countries such as the UK, however still placing at the lower end of the 'extreme danger zone' for offshore secrecy'. The island accounts of 0.46% of the global offshore finance market, making a small player in the total market.[130] In 2020, the Corporate Tax Haven Index ranked Jersey eighth for 2021 with a haven score (a measure of the jurisdiction's systems to be used for corporate tax abuse) of 100 out of 100; however, the island only has 0.51% on the Global Scale Weight ranking.[131]

Transport

[edit]

The primary mode of transport on the island is the motor vehicle. Jersey has a road network consisting of 346 miles (557 km) of roads and there are a total of 124,737 motor vehicles registered on the island as of 2016.[132] Jersey has a large network of lanes, some of which are classified as green lanes, which have a 15 mph speed limit and where priority is afforded to pedestrians, cyclists and horse riders.[133]

The public bus network in Jersey has been regulated by the Government since 2002, replacing a de-regulated, commercial service. It is operated on a sole-operator franchise model, currently contracted to LibertyBus, a company owned by Kelsian Group. LibertyBus also operate the school bus services.[134] There is also a taxi network and an electronic bike scheme (EVie).[135] Jersey has an airport and a number of ports, which are operated by Ports of Jersey.[136]

Currency

[edit]

Jersey's monetary policy is linked to the Bank of England. The official currency of Jersey is the pound sterling. Jersey issues its own postage stamps, banknotes (including a £1 note which is not issued in the UK) and coins that circulate alongside all other sterling coinage. Jersey currency is not legal tender outside Jersey; however it is "acceptable tender" in the UK and can be surrendered at banks in exchange for UK currency.[137]

In July 2014, the Jersey Financial Services Commission approved the establishment of the world's first regulated Bitcoin fund, at a time when the digital currency was being accepted by some local businesses.[138]

Demography

[edit]

Censuses have been undertaken in Jersey since 1821. In the 2021 census, the total resident population was estimated to be 103,267, of whom 35% live in St Helier, the island's only town.[139] Approximately half the island's population was born in Jersey; 29% of the population were born elsewhere in the British Isles, 8% in continental Portugal or Madeira, 9% in other European countries and 5% elsewhere.[140]

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1871 | 56,627 | — |

| 1951 | 55,244 | −2.4% |

| 1961 | 59,489 | +7.7% |

| 1971 | 69,329 | +16.5% |

| 1981 | 76,050 | +9.7% |

| 1991 | 84,082 | +10.6% |

| 2001 | 87,186 | +3.7% |

| 2011 | 97,857 | +12.2% |

| 2021 | 103,267 | +5.5% |

Nationality and citizenship

[edit]Jersey people are the native nation on the island;[28][29][30] however, they do not form a majority of the population.[140] Jersey people are often called Islanders or, in individual terms, Jerseyman or Jerseywoman. Jersey people did not generally identify themselves as English prior to the Union of Britain. Jersey was culturally and geographically much closer to Normandy and there were limited cross-Channel links. However, wars with France, including invasions of Jersey, grew loyalty to Britain over time and the French came more and more to be seen as a distinct people. By the start of the 19th century, Jersey people generally identified as British, which can be seen through the treatment of the Breton immigrants of the time as a distinct nation. Furthermore, the growth of the British migrant population strengthened the role of English and the British cultural influence. Finally, the introduction of compulsory education – which was exclusively in English – and the period of the Occupation reduced the traditional and Norman cultural influences and increased British cultural practices and pride in British nationhood among the island population.[141]

Nationality law in Jersey is conferred by the British Nationality Act 1981 extended to the island by an Order in Council with the consent of the States of Jersey. British nationality law confers British citizenship onto those with suitable connections to Jersey.[142][25] The Lieutenant Governor's office issues British passports (specifically the Jersey variant) to British citizens with a connection to Jersey by residency or birth.[143][144]

Immigration

[edit]Jersey is constitutionally entitled to restrict immigration[145] by non-Jersey residents, but control of immigration at the point of entry cannot be introduced for British, certain Commonwealth and EEA nationals without change to existing international law.[146]

Jersey is part of the Common Travel Area (CTA),[147] a zone which encompasses the Crown Dependencies, the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland. This means that for citizens of the Common Travel Area jurisdictions a passport is not required to travel from Jersey to any of these jurisdictions (or vice versa), though the Government recommends all travellers bring photo ID since it may need to be checked by customs or police officers, and is generally required by commercial transport providers into the island.[148] Due to the CTA, Jersey-born British citizens in the rest of the CTA and British and Irish citizens in Jersey have the right to access social benefits, access healthcare, access social housing support and to vote in general elections.[149]

For non-CTA travel, Jersey maintains its own immigration[150] and border controls (although most travel into the Bailiwick is from the rest of the CTA), however UK immigration legislation may be extended to Jersey (subject to exceptions and adaptations) following consultation with Jersey and with Jersey's consent.[151]

To control population numbers, Jersey operates a system of registration which restricts the right to live and work in the island according to certain requirements. To move to Jersey or work in Jersey, everyone (including Jersey-born people) must be registered and have a registration card. There are a number of statuses:

| Status | Requirements | Housing | Work |

|---|---|---|---|

| Entitled | Most Jersey-born residents (permanently) Long-term residents (at least 10 years) |

Can buy, sell or lease any property | Can work anywhere |

| Licensed | Certain essential workers | Can buy, sell or lease most property | Permission required |

| Entitled to work | Long-term residents (at least 5 years) Spouse or civil partner of someone who is entitled to work or higher. |

Can lease 'registered' property | Can work anywhere |

| Registered | All others | Can lease 'registered' property | Permission required |

History of immigration

[edit]Until the 19th century, there was generally limited immigration to the island, especially by English people. Jersey was quite far from Britain (taking days to travel between England and the islands)[citation needed] and culturally distinct (the locals predominantly speaking Norman French).[141] However, from the 16th to 19th centuries, Jersey became home to French religious refugees, particularly Protestants after the repeal of the Edict of Nantes.[153]

From the early 19th century, the island's economic boom attracted economic migrants. By 1841, of the 47,544 population, 11,338 were born in the British Isles outside of Jersey. From the 1840s onwards, agricultural workers came from neighbouring Brittany and mainland Normandy, both due to the booming economy of Jersey and the economic situation in northern France. Furthermore, the new potato season coincided with the time of least agricultural activity in Brittany and Normandy. While many returned to France, some settled in the island.[153]

Between 1851 and 1921, the Jersey population fell by 12.8% (possibly up to 18%). The economic boom ended in the 1850s leading to significant emigration, including to British colonies. A 1901 report by the States concluded that by 1921, the number of births to foreign-born fathers would be equal to those to Jersey-born fathers, describing the immigration situation as a "formidable invasion, although peaceful", and predicted this would have a large impact on the island's socio-political situation.[153]

After World War II, when the island had only 55,244 residents, it saw a period of rapid population increase. By 1991, the population was 84,082. The booming tourism industry required a large volume of relatively low cost labour, so the island turned to Madeira for seasonal staff. Between 1961 and 1981, the Portuguese-born population grew 0.2% to 3.1% of the population. In 2021, this figure was 8%. Since the fall of the Berlin Wall, the new source of cheap labour for the island has been Polish people, whose population has grown from non-existent to 3%.[153]

Immigration has helped give aspects of Jersey a distinct urban character, particularly in and around the parish of St Helier. This has led to ongoing debates about the incompatibility of development and sustainability throughout the island.[154]

Religion

[edit]

Jersey's patron saint is Saint Helier, after whom the capital town is named.[155] From the fifth century, the island was under the Bishop of Coutances, until being transferred to the Diocese of Winchester in 1568.[156] Jersey became "formally attached" to the Diocese of Salisbury in November 2022.[157] The established church is the Church of England, presided over in the island by the Dean, who is ex officio a States Member, but has no vote.[156] The primary churches are the parish churches, which are 12 ancient Anglican churches, one in each parish centre, though other churches do exist.[158]

According to a 2015 survey of islanders, 54% of adults have a religion. Christianity is the predominant religion in the island, with over half of islanders identifying as Christian in some form. The largest belief demographic is "no religion" with 39% of the population.[159]

| Religion | Percentage (2015) |

|---|---|

| No religion | 39% |

| All religious | 54% |

| Anglican | 23% |

| Catholic | 22.5% |

| Other Christian | 6.8% |

| Other religion | 3% |

Culture

[edit]

Cultural events

[edit]The Battle of Flowers is a carnival that has been held annually in August since 1902.[160] Other festivals include La Fête dé Noué[161] (Christmas festival), La Faîs'sie d'Cidre (cidermaking festival),[162] the Battle of Britain air display,[163] Weekender Music Festival,[164] food festivals, and parish events.

The Jersey Eisteddfod is an annual festival celebrating local culture. It is split into performing arts (e.g. dance, music, modern languages) and creative arts (e.g. needlework, photography, craft).[165]

Art

[edit]Archaeologists have discovered stone planquettes with abstract designs made by the Magdalenians and dating to the Upper Palaeolithic; these are the oldest pieces of art discovered in the British Isles as of 2023.[166][167]

The island has produced a number of notable artists. John St Helier Lander (1868–1944) was a portrait painter born in St Helier in 1868; he was a portraitist for the Royal Family.[168] Edmund Blampied also lived around the same period; he was known for his etchings and drypoint.[169] Other famous historic artists include John Le Capelain, John Everett Millais and Philip Ouless. There are also several contemporary Jersey artists, such as Ian Rolls, known for painting quirky landscape paintings.[170]

Jersey also has historic connections to French art. French artist René Lalique created the stained glass windows at St Matthew's Church. No similar Lalique commission survives elsewhere in the world.[171] Artist partners Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore were born in France but moved to and died in the island.[172]

Bergerac

[edit]The popular 1980s BBC detective drama Bergerac, starring John Nettles, was set in Jersey.

Media

[edit]

BBC Radio Jersey provides a radio service, and BBC Channel Islands News provides a joint television news service with Guernsey. ITV Channel Television is a regional ITV franchise shared with the Bailiwick of Guernsey but with its headquarters in Jersey. Radio services are also provided by Channel 103, among other companies.

Bailiwick Express is one of Jersey's digital online news sources. Jersey has only one newspaper, the Jersey Evening Post, which is printed six days a week, and has been in publication since 1890.[173]

Music

[edit]

Little is known of the history of music in the islands, though fieldwork has recorded folk songs from the Channel Islands, mostly in French.[175] The folk song Chanson de Peirson is unique to the island.[176]

In contemporary music, Guru Josh, who was born in Jersey, produced house and techno music. He was most notable for his internationally successful debut hit Infinity and its re-releases, reaching number one in numerous European countries.[177] Furthermore, rock and pop artist Nerina Pallot was raised on the island and has enjoyed international success, and has written songs for famous artists like Kylie Minogue.[178]

The island has a summer music festival scene stretching from mid-June to late September including Good Vibrations, Out-There, the Weekender (the largest festival in the Channel Islands) and Electric Park.[179]

Theatre

[edit]

There are two theatres on the island: the Jersey Opera House and the Jersey Arts Centre.[180] Lillie Langtry is probably the most famous actress from the island. She was born in Jersey and became an actress on the West End in the late 19th century. She was the first socialite to appear on stage and the first celebrity to endorse a commercial product.[181][182] She was also famous for her relationships with notable figures, including the Prince of Wales, later Edward VII.[183] She is buried in St Saviour's Church graveyard.[184]

Cinema

[edit]In 1909, T. J. West established the first cinema in the Royal Hall in St. Helier, which became known as West's Cinema in 1923 and was demolished in 1977. The first talking picture, The Perfect Alibi, was shown on 30 December 1929 at the Picture House in St. Helier. The Jersey Film Society was founded on 11 December 1947 at the Café Bleu, West's Cinema. The large Art Deco Forum Cinema was opened in 1935; during the German occupation this was used for German propaganda films.[185]

The Odeon Cinema was opened 2 June 1952 and was later rebranded in the early 21st century as the Forum cinema. Its owners, however, struggled to meet tough competition from the Cineworld Cinemas group, which opened a 10-screen multiplex on the waterfront centre in St. Helier on reclaimed land in December 2002, and the Odeon closed its doors in late 2008. The Odeon is now a listed building.[186][187]

First held in 2008, the Branchage Jersey International Film Festival[188] attracts filmmakers from all over the world. The 2001 movie The Others was set on the island in 1945 shortly after liberation.

Food and drink

[edit]

Seafood has traditionally been important to the cuisine of Jersey: mussels (called moules in the island), oysters, lobster and crabs – especially spider crabs – ormers and conger.[189]

Jersey milk being very rich, cream and butter have played a large part in insular cooking.[190] Jersey Royal potatoes are the local variety of new potato, and the island is famous for its early crop of Chats (small potatoes) from the south-facing côtils (steeply sloping fields). They were originally grown using vraic as a natural fertiliser, giving them their own individual taste; only a small portion of those grown in the island still use this method. They are eaten in a variety of ways, often simply boiled and served with butter or when not as fresh fried in butter.[191]

Apples historically were an important crop. Bourdélots are apple dumplings, but the most typical speciality is black butter (lé nièr beurre), a dark spicy spread prepared from apples, cider and spices. Cider used to be an important export. After decline and near-disappearance in the late 20th century, apple production is being increased and promoted. Besides cider, apple brandy is produced. Other production of alcohol drinks includes wine,[192] and in 2013 the first commercial vodkas made from Jersey Royal potatoes were marketed.[193]

Among other traditional dishes are cabbage loaf, Jersey wonders (les mèrvelles), fliottes, bean crock (les pais au fou), nettle (ortchie) soup, and vraic buns.[189][194]

Sport

[edit]

In its own right, Jersey participates in the Commonwealth Games and in the biennial Island Games, which it first hosted in 1997 and more recently in 2015.[195]

The Jersey Football Association supervises football in Jersey. As of 2022, the Jersey Football Combination has nine teams in its top division.[196] Jersey national football team plays in the annual Muratti competition against the other Channel Islands.[197] Rugby union in Jersey comes under the auspices of the Jersey Rugby Association (JRA), which is a member of the Rugby Football Union of England. Amateur side, Jersey RFC, won the English Regional Two South Central Division in the 2023/24 season and will play in fifth tier Regional One South Central next campaign.[198]

Jersey Cricket Board is the official governing body of the sport of cricket in Jersey. Jersey Cricket Board is Jersey's representative at the International Cricket Council (ICC). It has been an ICC member since 2005 and an associate member since 2007.[199] The Jersey cricket team plays in the Inter-insular match, as well as in ICC tournaments around the world in One Day Internationals and Twenty20 Internationals.

For Horse racing, Les Landes Racecourse can be found at Les Landes in St. Ouen next to the ruins of Grosnez Castle.[200]

Jersey has two public indoor swimming pools: AquaSplash, St Helier[201] and Les Quennevais, St Brelade.[202] Swimming in the sea, windsurfing and other marine sports are practised. Jersey Swimming Club has organised an annual swim from Elizabeth Castle to Saint Helier Harbour for over 50 years. A round-island swim is a major challenge: the record for the swim is Ross Wisby, who circumnavigated the island in 9 hours 26 minutes in 2015.[203] The Royal Channel Island Yacht Club is based in St Brelade.[204]

Two professional golfers from Jersey have won the Open Championship seven times between them; Harry Vardon won six times and Ted Ray won once, both around the turn of the 20th century. Vardon and Ray also won the U.S. Open once each. Harry Vardon's brother, Tom Vardon, had wins on various European tours.

Jersey Sport, an independent body that promotes sports in Jersey and support clubs, was launched in 2017[205]

Languages

[edit]Until the 19th century, indigenous Jèrriais – a variety of Norman – was the language of the island though French was used for official business. During the 20th century, British cultural influence saw an intense language shift take place and Jersey today is predominantly English-speaking.[27] Jèrriais nonetheless survives; around 2,600 islanders (three per cent) are thought to be habitual speakers, and some 10,000 (12 per cent) in all claim some knowledge of the language, particularly among the elderly in rural parishes. There have been efforts to revive Jèrriais in schools.[206]

The dialects of Jèrriais differ in phonology and, to a lesser extent, lexis between parishes, with the most marked differences to be heard between those of the west and east. Many place names are in Jèrriais, and French and English place names are also to be found. Anglicisation of the place names increased apace with the migration of English people to the island.[207]

Literature

[edit]

Wace was a 12th-century poet born in Jersey. He is the earliest known Jersey writer, authoring Roman de Brut and Roman de Rou, among others. Some believe him to be the earliest Jèrriais writer and he is known as the founder of Jersey literature, but the language in which he wrote is very different from modern Jèrriais.[15]

As Jèrriais was not an official language in Jersey, it had no standard written form, which meant that Jersey literature is very varied, written in multiple forms of Jèrriais alongside Standard English and French.[17]

Matthew Le Geyt was the first poet to publish in Jèrriais after the introduction of printing to the island in the 18th century.[208] Philippe Le Sueur Mourant wrote in Jèrriais in the 19th century.[18] Jerseyman George d'la Forge is named the 'Guardian of the Jersey Norman Heritage'. Though he lived in America for most of his life, he felt a strong attachment to Jersey and his native language. His works were turned into books in the 1980s.[19]

After the failure of the 1848 revolution, thirty-nine French revolutionaries were exiled in Jersey, including the famous French author Victor Hugo, as Jersey's culture had a relation to their native French.[22] Gerald Durrell, the famous zoologist who set up Jersey Zoo, was also an author, writing novels, non-fiction and children's books. He wrote in order to fund and further his conservation work.[24]

Education

[edit]Education in the island is managed by the Department for Children, Young People, Education and Skills of the Government of Jersey. The education system in Jersey is based on the English system. Full time education is compulsory for children aged 5 to 16.[209] Furthermore, the Government provides limited pre-school education free to parents.[210] Jersey schools must teach the Jersey Curriculum, which is based on the English National Curriculum, with differences to account for Jersey's unique position.[211]

As of 2022, there are 24 States primary schools, seven private primary or preparatory schools, four comprehensive States secondary schools, two fee-paying States secondary schools, two private secondary schools and one provided grammar school and sixth form, Hautlieu School.[212] Furthermore, Highlands College provides alternative post-16 and all post-18 education available on the island. However, higher education facilities are limited, so many students study off-island. In the UK, Jersey students pay the same rate as Home students.[213]

Environment

[edit]| Designations | |

|---|---|

| Official name | South East Coast of Jersey, Channel Islands |

| Designated | 10 November 2000 |

| Reference no. | 1043[214] |

Three areas of land are protected for their ecological or geological interest as Sites of Special Interest (SSI). Jersey has four designated Ramsar sites: Les Pierres de Lecq, Les Minquiers, Les Écréhous and Les Dirouilles and the south east coast of Jersey (a large area of intertidal zone).[215]

Jersey is the home of the Jersey Zoo (formerly known as the Durrell Wildlife Park[216]) founded by the naturalist, zookeeper and author Gerald Durrell.

Biodiversity

[edit]Four species of small mammal are considered native:[217] the wood mouse (Apodemus sylvaticus), the Jersey bank vole (Myodes glareolus caesarius), the lesser white-toothed shrew (Crocidura suaveolens) and the French shrew (Sorex coronatus). Three wild mammals are well-established introductions: the rabbit (introduced in the mediaeval period), the red squirrel and the hedgehog (both introduced in the 19th century). The stoat (Mustela erminea) became extinct in Jersey between 1976 and 2000. The green lizard (Lacerta bilineata) is a protected species of reptile; Jersey is its only native habitat in the British Isles.[218]

The red-billed chough (Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax) became extinct in Jersey around 1900, when changes in farming and grazing practices led to a decline in the coastal slope habitat required by this species. Birds on the Edge, a project between the Government of Jersey, Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust and National Trust for Jersey, is working to restore Jersey's coastal habitats and reinstate the red-billed chough (and other bird species) to the island[219]

Jersey is the only place in the British Isles where the agile frog (Rana dalmatina) is found.[220] The remaining population of agile frogs on Jersey is very small and is restricted to the south west of the island. The species is the subject of an ongoing programme to save it from extinction in Jersey via a collaboration between the Government of Jersey, Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust and Jersey Amphibian and Reptile Group (JARG), with support and sponsorship from several other organisations. The programme includes captive breeding and release, public awareness and habitat restoration activities.[221]

Trees generally considered native are the alder (Alnus glutinosa), silver birch (Betula pendula), sweet chestnut (Castanea sativa), hazel (Corylus avellana), hawthorn (Crataegus monogyna), beech (Fagus sylvatica), ash (Fraxinus excelsior), aspen (Populus tremula), wild cherry (Prunus avium), blackthorn (Prunus spinosa), holm oak (Quercus ilex), oak (Quercus robur), sallow (Salix cinerea), elder (Sambucus nigra), elm (Ulmus spp.) and medlar (Mespilus germanica). Among notable introduced species, the cabbage palm (Cordyline australis) has been planted in coastal areas and may be seen in many gardens.[222]

Notable marine species[223] include the ormer, conger, bass, undulate ray, grey mullet, ballan wrasse and garfish. Marine mammals include the bottlenosed dolphin[224] and grey seal.[225]

Historically the island has given its name to a variety of overly-large cabbage, the Jersey cabbage, also known as Jersey kale or cow cabbage.[226]

Japanese knotweed (Reynoutria japonica) is an invasive species that threatens Jersey's biodiversity.[227] It is easily recognisable and has hollow stems with small white flowers that are produced in late summer.[228] Other non-native species on the island include the Colorado beetle, burnet rose and oak processionary moth.[227]

Public services

[edit]Healthcare

[edit]Health services on the island are overseen by the Department for Health and Social Care. Jersey does not have a nationalised health service and the service is not part of the National Health Service. Many healthcare treatments are not free at the point of use, however treatment in the accident and emergency department is free. For residents, prescriptions and some hospital treatments are free, but GP services cost money.[229]

Emergency services

[edit]Emergency services[230] are provided by the States of Jersey Police with the support of the Honorary Police as necessary, States of Jersey Ambulance Service,[231] Jersey Fire and Rescue Service[232] and the Jersey Coastguard.[233] The Jersey Fire and Rescue Service, Jersey Lifeboat Association and the Royal National Lifeboat Institution operate an inshore rescue and lifeboat service; Channel Islands Air Search provides rapid response airborne search of the surrounding waters.[234]

The States of Jersey Fire Service was formed in 1938 when the States took over the Saint Helier Fire Brigade, which had been formed in 1901. The first lifeboat was equipped, funded by the States, in 1830. The RNLI established a lifeboat station in 1884.[235] Border security and customs controls are undertaken by the States of Jersey Customs and Immigration Service. Jersey has adopted the 112 emergency number alongside its existing 999 emergency number.[236]

Supply services

[edit]Water supplies in Jersey are managed by Jersey Water. Jersey Water supply water from two water treatment works, around 7.2 billion litres in 2018. Water in Jersey is almost exclusively from rainfall-dependent surface water. The water is collected and stored in six reservoirs and there is also a desalination plant that produces up to 10.8 million litres per day (around half of the Island's average daily usage). In 2017, 101 water pollution incidents were reported, an increase of 5% on 2016. Another estimated 515,700 m3 of water is abstracted for domestic purposes from private sources (around 9% of the population).[237]

Electricity in Jersey is provided by a sole supplier, Jersey Electricity, of which the States of Jersey is the majority shareholder.[238] Jersey imports 95 per cent of its power from France.[239] 35% of the imported power derives from hydro-electric sources and 65% from nuclear sources. Jersey Electricity claims the carbon intensity of its electricity supply is 35g CO2 e / kWh compared to 352g CO2 e / kWh in the UK.[240]

Notable people

[edit]See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ St Helier is the de facto capital of Jersey, being the seat of the island's government, however Government House, the official royal residence of the island, is located in Saint Saviour

- ^ The largest settlement in Jersey is in fact made up of parts of various parishes and is often referred to as "town" by islanders.

- ^ Jersey does not have a de jure official language, but these are the permitted languages in the island's parliament, the States Assembly "P.4/2018 – Jèrriais: Optional use in the States Chamber" (PDF). States of Jersey Greffe. 15 January 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 January 2021. Retrieved 4 January 2021. The official working and most widely spoken language is English, though French retains a historical and ceremonial working role.

- ^ French: Bailiage de Jersey; Jèrriais: Bailiage d'Jèrri

- ^ Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, Article 355(5)(c) TFEU states "the Treaties shall apply to the Channel Islands and the Isle of Man only to the extent necessary to ensure the implementation of the arrangements for those islands set out in the Treaty concerning the accession of new Member States to the European Economic Community and to the European Atomic Energy Community signed on 22 January 1972".

- ^ Geographically it is not part of the British Isles. As of 15 October 2006, the States of Jersey indicates that the island is situated "only 22 km off the northwest coast of France and 140 km south of England".

References

[edit]- ^ Fact sheet on the UK's relationship with the Crown Dependencies (PDF), UK Ministry of Justice, archived (PDF) from the original on 20 December 2021, retrieved 2 May 2023,

The Crown Dependencies are not recognised internationally as sovereign States in their own right but as "territories for which the United Kingdom is responsible".

- ^ Framework for developing the international identity of Jersey (PDF), Government of Jersey, archived (PDF) from the original on 31 January 2021, retrieved 2 May 2023,

2. Jersey has an international identity which is different from that of the UK.

- ^ "Anthem for Jersey". Government of Jersey. Archived from the original on 23 October 2019. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- ^ "Bulletin 2: Place of birth, ethnicity, length of residency, marital status". Government of Jersey. Archived from the original on 10 August 2022. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- ^ Jersey Annual Social Survey: 2015 (PDF). States of Jersey. p. 8. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Jersey in Figures 2013 booklet" (PDF). Government of Jersey. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 February 2021. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- ^ a b "First Census Results Published". 13 April 2022. Archived from the original on 13 April 2022. Retrieved 13 April 2022.

- ^ "Measuring Jersey's Economy" (PDF). Government of Jersey. 28 September 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 January 2017. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- ^ a b "National accounts: GVA and GDP". Statistics Jersey. 2019. Archived from the original on 7 January 2021. Retrieved 4 January 2021.

- ^ "Gini Index coefficient". CIA World Factbook. Archived from the original on 17 July 2021. Retrieved 16 July 2021.

- ^ "Filling Gaps in the Human Development Index" (PDF). United Nations ESCAP. February 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 October 2011.

- ^ "Jersey | island, Channel Islands, English Channel". Britannica. Archived from the original on 25 April 2023. Retrieved 16 May 2023.

- ^ Balleine, G.R. (1951). Bailiwick of Jersey (King's Channel Islands series). London: Hodder And Stoughton.

- ^ Tilbrook, Richard (2 September 2022), "09.020 – Attachment of Jersey to the Diocese of Salisbury Order 2022", Unofficial extended UK law, Jersey Legal Information Board, archived from the original on 16 May 2023, retrieved 16 May 2023,

HER MAJESTY, in the exercise of Her prerogatives as Sovereign in right of the Bailiwick of Jersey ... The Bailiwick of Jersey is, by virtue of this Order, as a matter of and for the purposes of the law of Jersey

- ^ a b "Definition: What is a country?". Worlddata.info. Archived from the original on 28 April 2019. Retrieved 25 February 2022.

- ^ "Constitution and citizenship". Government of Jersey – Island Identity. Archived from the original on 27 May 2022. Retrieved 18 July 2022.

The Board concluded that Jersey is accurately described as a 'Country', or even as a 'Small Island Nation', and as such has a distinct international character. This has been agreed with the UK and by constitutional experts, and in 2007 the Lord Chancellor and Chief Minister signed an agreement entitled 'Framework for developing the international identity of Jersey', which also acknowledges that Jersey's 'international identity' is different from that of the UK. However, legally-speaking the term 'identity' has no defined meaning; the appropriate term for a country is 'personality', and this report adopts that usage throughout when describing how we are viewed internationally.

- ^ a b "Facts about Jersey". Government of Jersey. Archived from the original on 21 December 2019. Retrieved 2 March 2017.

- ^ a b "Facts about Jersey". Government of Jersey. Archived from the original on 21 December 2019. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ^ a b "Les Écrehous & Les Dirouilles, Jersey". Ramsar Sites Information Service. Archived from the original on 22 July 2018. Retrieved 25 April 2018.; "Les Minquiers, Jersey". Ramsar Sites Information Service. Archived from the original on 26 October 2018. Retrieved 25 April 2018.; "Les Pierres de Lecq". Ramsar Sites Information Service. Archived from the original on 22 July 2018. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- ^ "Plans to celebrate Liberation 75". gov.je. Archived from the original on 5 May 2023. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- ^ "COMMON POLICY FOR EXTERNAL RELATIONS" (PDF). Government of Jersey. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 8 December 2012.

- ^ a b "Crown Dependencies". Royal.gov.uk. 4 June 2018. Archived from the original on 11 July 2021. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- ^ Committee, European Union (23 March 2017). Brexit: the British Crown Dependencies (PDF) (Report). House of Lords. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 April 2021. Retrieved 6 May 2021. (Summary, first sentence; Paragraph 4)

- ^ a b Mut Bosque, Maria (May 2020). "The sovereignty of the British Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories in the Brexit era". Island Studies Journal. 15 (1): 151–168. doi:10.24043/isj.114.

- ^ a b Torrance, David (20 June 2022). The Crown Dependencies (PDF) (Report). House of Commons Research Library. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 October 2021. Retrieved 16 November 2022.

- ^ "Understanding the curriculum". Government of Jersey. 30 November 2015. Archived from the original on 5 September 2013. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- ^ a b "Facts about Jersey". Government of Jersey. 30 November 2015. Archived from the original on 21 December 2019. Retrieved 2 March 2017.

- ^ a b Minahan, James (2000). One Europe, Many Nations: A Historical Dictionary of European National Groups. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 349. ISBN 978-0-313-30984-7. Archived from the original on 30 June 2023. Retrieved 4 May 2021 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b Quayle, T. (1815). A general view of the agriculture and present state of the islands on the coast of Normandy. London: Board of Agriculture. p. 48.

- ^ a b "Island Identity Interim Report" (PDF). Government of Jersey. Island Identity Policy Development Board. 11 May 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 May 2021. Retrieved 11 May 2021.

- ^ Dominique Fournier, Wikimanche.

- ^ Marguerite Syvret; Joan Stevens (1998). Balleine's History of Jersey. La Société Jersiaise. ISBN 1-86077-065-7.

- ^ "The Duke of York's Release to John Lord Berkeley, and Sir George Carteret, 24th of June, 1664". avalon.law.yale.edu. 18 December 1998. Archived from the original on 6 September 2011. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

- ^ "So what's all this stuff about Nova Caesarea??". avalon.law.yale.edu. Archived from the original on 11 February 2021. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

- ^ Antonine Itinerary, fourth century

- ^ "History of stamps". Jersey Post. Archived from the original on 8 May 2006. Retrieved 6 October 2006.

- ^ Everett-Heath, John. The Concise Dictionary of World Place-Names. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 11 May 2021. Retrieved 16 May 2021 – via www.oxfordreference.com.

- ^ Lepelley, René (1999). Noms de lieux de Normandie et des îles Anglo-Normandes. Paris: Bonneton. ISBN 2862532479.

- ^ "Old Norse Words in the Norman Dialect". Viking Network. Archived from the original on 15 November 2018. Retrieved 30 August 2016.

- ^ Cunliffe, Barry (1994). The Oxford Illustrated Prehistory of Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198143850.

- ^ "Countryside Character Appraisal – Character Area A1: North Coast Heathland". States of Jersey. Archived from the original on 19 March 2016. Retrieved 6 October 2006.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Syvret, Marguerite (2011). Balleine's History of Jersey. The History Press. ISBN 978-1860776502.

- ^ "ST HELIER: THE MAN AND THE MYTH". members.societe-jersiaise.org. Archived from the original on 18 August 2022. Retrieved 17 March 2022.

- ^ a b Lempière, Raoul (1976). Customs, Ceremonies and Traditions of the Channel Islands. Great Britain: Robert Hale. ISBN 0-7091-5731-2.

- ^ Ommer, Rosemary E. (1991). From Outpost to Outport. McGill-Queen's University Press. pp. 13–14. ISBN 0-7735-0730-2. Archived from the original on 30 June 2023. Retrieved 14 November 2020.

- ^ Weeks, Daniel J. (1 May 2001). Not for Filthy Lucre's Sake. Lehigh University Press. p. 45. ISBN 0-934223-66-1. Archived from the original on 30 June 2023. Retrieved 14 November 2020.

- ^ Cochrane, Willard W. (30 September 1993). The Development of American Agriculture. University of Minnesota Press. p. 18. ISBN 0-8166-2283-3. Archived from the original on 30 June 2023. Retrieved 14 November 2020.

- ^ "1781 The Battle Of Jersey". Jersey Heritage. 5 July 2021. Archived from the original on 4 April 2022. Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- ^ Kelleher, John D. (1991). The rural community in nineteenth century Jersey (Thesis). S.l.: typescript. Archived from the original on 28 March 2021. Retrieved 17 March 2022.

- ^ Bunting, Madeleine (1995). The Model Occupation. London: Harper Collins. p. 21. ISBN 0002552426.

- ^ Bellows, Tony. "What was the "Occupation" and why is "Liberation Day" celebrated in the Channel Islands?". Société Jersiaise. Archived from the original on 2 November 2013. Retrieved 18 August 2013.

- ^ Bunting 1995, pp. 151–154.

- ^ Meddick, Simon; Payne, Liz; Catz, Phil (2020). Red Lives: Communists and the Struggle for Socialism. UK: Manifesto Press Cooperative Limited. pp. 122–123. ISBN 978-1-907464-45-4.

- ^ House of Commons, Justice Committee (23 March 2010). Crown dependencies (PDF). Vol. 8th Report of Session 2009–10. London: The Stationery Office. ISBN 978-0-215-55334-8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 July 2017. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ Brexit Information Report (PDF) (Report). Jersey: States Greffe. 27 June 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 February 2021. Retrieved 6 January 2021.

- ^ Jersey Law Review. "Lé Rouai, Nouot' Duc". Archived from the original on 16 October 2014. Retrieved 12 October 2014.

- ^ "Public Hearing – Review of the Roles of the Crown Officers" (PDF). 20 July 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 August 2011.

- ^ Office of the Lieutenant Governor. "Lieutenant-Governor". Archived from the original on 12 August 2011. Retrieved 22 August 2011.

- ^ Royal Commission on the Constitution 1969–1973 (1973). Report. Vol. Part XI of Volume 1. London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "States of Jersey (Miscellaneous Provisions) Law 2011". Jerseylaw.je. 2 August 2011. Archived from the original on 22 October 2013. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- ^ a b Shaxson, N. (2011). Treasure islands: Tax havens and the men who stole the world. London: The Bodley Head.

- ^ "Politicians bat away last-ditch attempt to save Senators". Bailiwick Express. Archived from the original on 22 April 2021. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ^ "States of Jersey Law 2005, Article 1". Jerseylaw.je. 5 May 2006. Archived from the original on 3 October 2011. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- ^ "States of Jersey Law 2005, Article 3". Jerseylaw.je. 5 May 2006. Archived from the original on 3 October 2011. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- ^ a b Gindill, J. (n.d.) The Role of the Office of Bailiff: The Need for Reform Archived 3 April 2022 at the Wayback Machine. University of Durham.

- ^ "Council of Ministers adopts 'Government of Jersey' identity". Government of Jersey. Archived from the original on 10 February 2019. Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- ^ "States of Jersey Law 2005, Article 18". Jerseylaw.je. 5 May 2006. Archived from the original on 3 October 2011. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- ^ "States of Jersey Law 2005, Article 24". Jerseylaw.je. 5 May 2006. Archived from the original on 3 October 2011. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- ^ States of Jersey Official Report, 3 May 2011, 5.1. Statement by the Chief Minister regarding the appointment of a new Chief Executive to the Council of Ministers.

- ^ a b c Legislation Committee (2001) R.2001/120 – THE WORKING PARTY ON PARISH ASSEMBLIES: REPORT Archived 20 January 2022 at the Wayback Machine. Presented to the States: 4 December 2001. States Greffe (gov.je) [Accessed: 18 March 2022].

- ^ Collins of Mapesbury, Lord; More; McLean; Briggs; Harris; McLachlan (2010). Dicey, Morris & Collins on the Conflict of Laws (14th ed.). London: Sweet & Maxwell. ISBN 978-1-84703-461-8.

- ^ See generally S Nicolle (2009). The Origin and Development of Jersey law: an Outline Guide (5th ed.). St Helier: Jersey and Guernsey Law Review. ISBN 978-0-9557611-3-3. and "Study Guide on Jersey Legal System and Constitutional Law". Jersey: Institute of Law. Archived from the original on 28 December 2013.

- ^ Hanson, T. (2005). THE LANGUAGE OF THE LAW: THE IMPORTANCE OF FRENCH. Archived 6 January 2022 at the Wayback Machine The Jersey Law Review. June 2005.

- ^ "The Royal Court". Jersey Courts. Archived from the original on 4 August 2012.

- ^ "Meet our new foreign minister « This Is Jersey". Thisisjersey.com. Archived from the original on 17 January 2011. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "A new role of great importance". Thisisjersey.com. 17 January 2011. Archived from the original on 22 January 2011. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Framework for developing the international identity of Jersey" (PDF). Government of Jersey. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 July 2013. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- ^ "TAX INFORMATION EXCHANGE AGREEMENTS (TIEAs)" (PDF). Government of Jersey. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 March 2012. Retrieved 6 November 2011.

- ^ "Jersey threatens to break with UK over tax backlash". The Guardian. 26 June 2012. Archived from the original on 4 February 2021. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- ^ "The Office | Bureau des Îles Anglo-Normandes". Archived from the original on 3 February 2021. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- ^ "Government of Jersey London Office | Representing Jersey in the UK". Government of Jersey London Office. 27 March 2017. Archived from the original on 4 February 2021. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- ^ "Channel Islands Brussels Office (CIBO)". Channel Islands Brussels Office (CIBO). Archived from the original on 23 January 2021. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- ^ "Jersey". British-Irish Council. 7 December 2011. Archived from the original on 4 April 2022. Retrieved 17 March 2022.

- ^ "States of Jersey". www.cpahq.org. Archived from the original on 3 April 2022. Retrieved 17 March 2022.

- ^ "Jersey". Assemblée Parlementaire de la Francophonie (APF) (in French). Archived from the original on 3 April 2022. Retrieved 17 March 2022.

- ^ Targett, Tania (23 June 2018). "Independence 'may be only option if Brexit deal is bad'". jerseyeveningpost.com. Archived from the original on 31 January 2021. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- ^ "COMMON POLICY FOR EXTERNAL RELATIONS" (PDF). States of Jersey. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 July 2013. Retrieved 8 December 2012.

- ^ "Jersey Independence 'Not Government Policy'". Channel 103. Archived from the original on 4 February 2021. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- ^ Council of Ministers (27 June 2008). "Second Interim Report of the Constitution Review Group" (PDF). States Greffe. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 January 2022. Retrieved 16 March 2022.

- ^ "France threatens to cut power to Jersey amid fishing row". BBC News. 4 May 2021. Archived from the original on 5 May 2021. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

- ^ "EUR-Lex – 61996J0171 – EN". European Court reports 1998 Page I-04607. Archived from the original on 16 May 2021. Retrieved 16 May 2021.

- ^ States of Jersey Brexit Report (PDF) (Report). 31 January 2017. p. 7. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 September 2021. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ^ Jersey, States of. "Government of Jersey". gov.je. Retrieved 9 June 2024.

- ^ "'This Map of the Island of Jersey divided into Parishes and Vingtaines...' (AO0398) Archive Item – Ordnance Survey Collection | Historic England". historicengland.org.uk. Archived from the original on 18 March 2022. Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- ^ "Ascent of Jersey High Point on 2009-09-12". Peakbagger.com. Archived from the original on 18 March 2022. Retrieved 23 June 2012.

Sources vary on the elevation of Les Platons. Its height is often listed at 143 m, as well as 136 m.

- ^ a b Jersey. "Size and land cover of Jersey". Government of Jersey. Archived from the original on 2 November 2020. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ^ "About Nine by Five Media". Medium. Archived from the original on 18 March 2022. Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- ^ "Les Platons (Jersey) | Channel Islands". UK mountain Guide. Archived from the original on 1 February 2021. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ^ "The Minquiers and Écréhous in spatial context: Contemporary issues and cross perspectives on border islands, reefs and rocks". ResearchGate. Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- ^ Willie Miller Urban Design (2005) strategic context Archived 11 April 2022 at the Wayback Machine in St Helier Urban Character Appraisal.

- ^ "Jersey Census 2001: Chapter 2: Population Characteristics" (PDF). States of Jersey. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 March 2013. Retrieved 15 November 2018.

- ^ "Archives and collections online". Jersey Heritage. Archived from the original on 9 April 2022. Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- ^ "Les Quennevais". www.active.je. Archived from the original on 26 March 2022. Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- ^ "A Framework for a Sustainable Transport System: 2020–2030". Government of Jersey. Archived from the original on 18 March 2022. Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- ^ "Jersey House Price Index Q4 2020". Government of Jersey. Archived from the original on 18 February 2021. Retrieved 18 February 2021.

- ^ "CIA – The World Factbook – Jersey". Central Intelligence Agency. 5 October 2006. Archived from the original on 13 January 2021. Retrieved 7 October 2006.

- ^ "Jersey records hottest ever day as temperatures top 36°C". Jersey Evening Post. 18 July 2022. Archived from the original on 18 July 2022. Retrieved 18 July 2022.

- ^ "Government of Jersey".

- ^ "In pictures: Jersey gets more than 5.5 inches (14cm) of snowfall". BBC News. 12 March 2013. Retrieved 25 July 2024.

- ^ Jersey, States of. "Government of Jersey". gov.je. Retrieved 25 July 2024.

- ^ https://x.com/JsyFire/status/1719955319512563725.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ https://www.torro.org.uk/pdf/SI/SI20231101_Jersey.pdf.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "Record high temperatures verified". Met Office. Retrieved 25 July 2024.